Abstract

Many African countries have a shortage of health workers. As a response, in 2012, the Ministers of Health in the WHO African Region endorsed a Regional Road Map for Scaling Up the Health Workforce from 2012 to 2025. One of the key milestones of the roadmap was the development of national strategic plans by 2014. It is important to assess the extent to which the strategic plans that countries developed conformed with the WHO Roadmap. We examine the strategic plans for human resource for health (HRH) of sub-Saharan African countries in 2015 and assess the extent to which they take into consideration the WHO African Region’s Roadmap for HRH. A questionnaire seeking data on human resources for health policies and plans was sent to 47 Member States and the responses from 43 countries that returned the questionnaires were analysed. Only 72% had a national plan of action for attaining the HRH target. This did not meet the 2015 target for the WHO, Regional Office for Africa’s Roadmap. The plans that were available addressed the six areas of the roadmap. Despite all their efforts, countries will need further support to comprehensively implement the six strategic areas to maintain the health workers required for universal health coverage

Keywords: human resources for health, national strategic plans, health workforce, national policies

Summary box.

In 2015, only 36% of the 47 countries had developed human resource for health (HRH) policy.

From 2010 to 2015, the number of countries with HRH strategic plans increased from 20 to 34 which, however, did not meet the target to have all countries with HRH strategic plans by the end of 2014, as targeted by the AFRO (WHO Regional Office for Africa) Regional Roadmap.

Regarding the content of the existing HRH plans, most of them are aligned with the six strategic areas of the

A good HRH strategic plan will serve as part of the vehicle for implementing universal health coverage within the broader national health policies and plans.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries have the most severe shortage of human resource for health (HRH) in the world. More than 60% of countries with an extreme shortage of HRH are found in the African region.1 In some countries, the shortage is so severe as to constitute a crisis in the health sector and to have a direct effect on the achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and particularly the realisation of the universal health coverage (UHC).2 3 Inability to meet the HRH creates a gap in service delivery that in turn impedes the delivery of primary healthcare in Africa to an acceptable level.4 It is dismay that less than 30% of the counties in the region are able to meet the target of 2.3 health worker per 1000 people, which was set by the WHO.1

The shortage of health workers in SSA is attributed primarily to high attrition rates, inability to produce and recruit the appropriate cadres of health workers.5–9 A strategic, integrated and multifaceted approach is required in order to properly address the various factors that affect the shortage of health workers in the region.10

One of the steps taken to assist SSA countries for bridging the gap in their health workforce is the development of guidelines for preparing national HRH policies and strategic plans.11 The ownership of a comprehensive national HRH strategy is an indication of a country’s commitment to address the HRH challenges and to build an effective, sustainable, resilient health system. The HRH strategic plans are necessary for attracting technical and other resource support from partners. The HRH plan is also useful for monitoring the performance, HRH coordination mechanism, deployment and retention in rural areas.12

In 2012, the Ministers of Health of the WHO African Region endorsed a Regional Roadmap for Scaling Up the Health Workforce for Improved Health Service Delivery in the African Region: 2012–2025.13 The roadmap provided the guideline with six strategic directions that will assist countries in developing their HRH strategic plans by all countries by 2014.

The global attention to the critical shortage of health workers in the region in the early 2000s and the roadmap motivated the development of HRH plans.

In this analytical paper, we identified SSA countries with HRH strategic plans and policies up to and including 2015. We then reviewed the plans and assessed the extent of conformity with the WHO African Region’s Roadmap for HRH, which has its goal, to ensure that skilled and motivated health workers are available for UHC of essential health services. SSA countries were classified according to size, health system (decentralised or centralised), the evolution of the national health system and health system situation (distortion due to conflict or not distorted). Twelve countries (Benin, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Guinea Bissau, Seychelles, Sao Tome and Principe, South Africa, Rwanda, Togo, Tanzania and Uganda) were then randomly selected to ensure that these categories were represented in our analysis (online supplementary appendix)

bmjgh-2018-001115supp001.pdf (75.4KB, pdf)

HRH policies and strategic plan

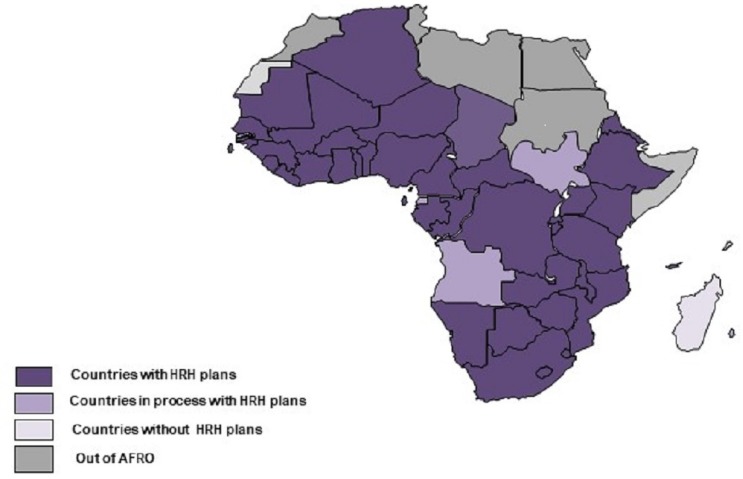

In 2015, only 17 countries (representing a mere 36%) in the African Region had a policy specifically for HRH but 34 had strategic plans (figure 1). Six of those that did not have policy plans and 10 without strategic plans had commenced the process of developing them. Normally, policies have a time frame of implementation after which new ones are developed. We note that some countries embed the strategic plan in the policy, while others retained the expired policy and paid attention to develop a new strategy. This may be responsible for the difference in the number of policies that were available relative to the strategic plans14 over time and between 2010 and 2015.

Figure 1.

Countries in the African region with human resource for health (HRH) strategic plans, 2015.

Countries are keener to invest in developing strategic plans than making new policies when an old one expires, perhaps due to perceived continuity of the political and economic landscape. Sadly, the region did not hit the mark set in the WHO Regional Office for Africa's Roadmap requiring all SSA countries to have HRH policy and strategic plans by the end of 2014. Only 14 countries had comprehensive national HRH strategic plans by the end of 2014, still a far cry from the target. Nevertheless, the increase in the number of countries with strategic plans is gladdening as it shows that countries are prioritising the commitment to address workforce issues. Countries with well-developed plans can use them for advocating for investment in health from domestic and global stakeholders.15–17 A strategic approach to HRH planning and management will make a significant contribution to the rapid attainment of a UHC and influence the achievement of health-related SDGs.18 19

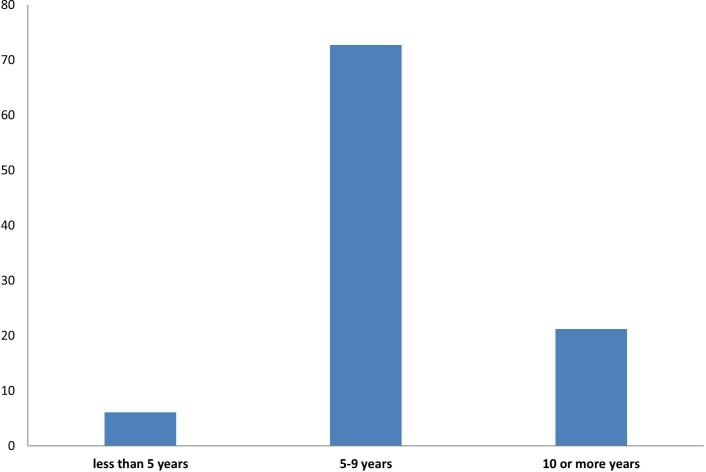

Six of the 11 countries in which the shortage of health workers was not critical had policy plans indicating that the possession of policy plans probably influence the achievement. The strategic plans were comprehensive and had a specific time frame for implementation (figure 2). Two of the countries had a time frame that is less than 5 years; 72% had a time frame of 5–9 years and the remaining had time frame of more than 10 years.

Figure 2.

Proportion of human resource for health (HRH) strategic plans with stated time frames.

Leadership and governance capacity of the health workforce

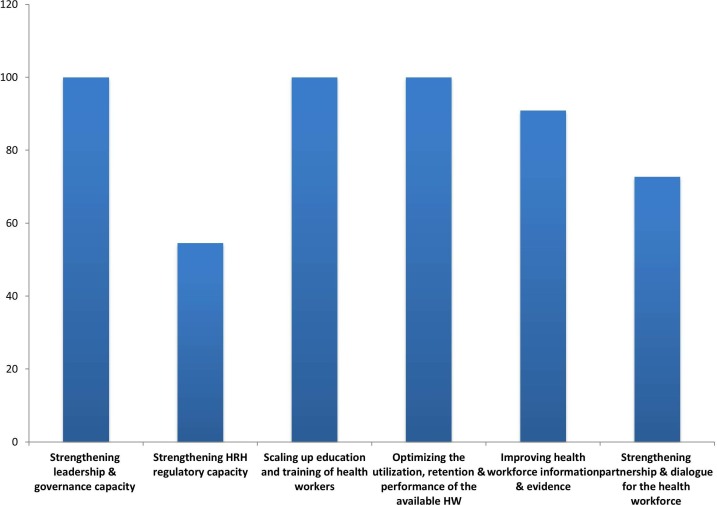

Strengthening leadership and governance capacity entails improving policy dialogue and establishing clear mechanisms for coordination between line ministries, the private sector and other stakeholders. All the HRH plans (policy or strategic) identified leadership and governance as one of the strategic areas that the plans would address (figure 3). They also described a wide range of activities for developing the capacities of the leadership and management at central, provincial and district levels. The Cameroon HRH plan included the strengthening of the capacities of decision-makers and HRH managers on governance and ethics skills. Only 25% of the plans emphasised the need to decentralise HRH management to align with the country’s governance structure, a third explicitly described how they will manage financial sustainability to address HRH. Only 8.3% of HRH plans mentioned establishing a national finance committee to analyse and advise on health expenditure in terms of health workers and the financing of workforce development. Less than 10% of the plans anticipated that a country’s growing gross domestic product will increase the health budget, which will subsequently increase HRH salaries.

Figure 3.

Percentage of human resource for health (HRH) plans in line with regional roadmap strategic areas.

Leadership and governance have a major influence on HRH challenge in the region. Leadership and governance ensure effective coordination and harmonisation of activities in addition to check listing the plans into clear deliverables.20–22 It was not clear whether the leadership and governance of HRH referred to the health system or national governance of it, which is an important factor with respect to sustainability and effectiveness.23 24 Countries will require an appreciable increase in funding of the implementation of their plans as well as ensure the sustainability of financing for the strategic plans to come into fruition. Previous studies on HRH plans documented similar inadequate calculation of planned activities.25 HRH receives less than 30% of the total Development Assistance for Health, thus, limiting the fund for implementing HRH plans.26 Although external investment is necessary for addressing workforce issues at the initial stage, sustaining it depends on the government’s innovativeness and strategies for mobilising domestic resources to fund both activities that the plans had identified as critical.27

HRH regulatory capacity

The HRH regulatory capacity implies the establishment of a professional and regulatory mechanism such as health professional councils that will assure the production of the quality health workforce and provide continuous on the job support to health workers. Approximately 55% of the HRH plans addressed some aspects of HRH regulatory capacity as shown in figure 3. Half of the HRH plans identified improving processes for the accreditation of training institutions and licensing health professionals as a priority. About 17% of the HRH plans recognised the need to extend regulation to allied health workers such as Allied Health Professionals and Clinical Associates through legislation. There was no mention of the traditional health professionals. Less than 10% of the plans indicated the strengthening of the capacity of members of the regulatory bodies on good governance as a priority. A similar proportion of the HRH plans indicated strengthening the capacity of regulatory council members’ leadership responsibility but without stating the mechanism for carrying it through, nor do they provide details of how the councils will ensure the quality of in-service training. Some of the plans mention the development of a legal framework to regulate the private sector and adopt a regulation for a National Health Council.

Strengthening HRH regulatory capacity was addressed by less than 60% of the plans. Despite this, it had been shown that many countries in the region do not have enough capacity or resources to strengthen regulation for HRH.28 In addition, there has been an increase in the creation of mid-level and low-level cadre of health workers which need to be regulated.29 The plans that acknowledged the need to strengthen regulatory councils and professional bodies did not specify how they would be supported to carry through the recommended responsibilities. Countries should focus on developing policies and practices to strengthen existing regulatory councils and to establish regulatory councils for emerging cadres of health professionals.

Scaling up education and training of health workers

The production of health workers is dependent on matching investment into the process of training with meeting the demand for the different cadre of health workers. One of the strategic areas that all the HRH plans included was the scaling up of the process for producing an adequate number in various categories to meet the demand through health worker education and training (figure 3). These plans included increasing the number of health workers to meet the WHO target but only 42% of the plans specifically identified the cadres of health workers that they would want to be increased. Examples are anaesthetic technicians, surgical technicians and emergency surgical officers. Most plans stated the scaling up of production of health workers through teacher training, developing infrastructure and increasing teaching equipment. It is important to identify the relative distribution of one health cadres compared with another per population based on demand. The plans noted to use incentives for attracting trainees especially for cadres where there is critical shortage such as midwives. Improving the quality of education was emphasised in 67% of the HRH plans. However, only 33% of the plans specifically mentioned adapting and improving curricula for training institutions based on the needs of the health system. In addition, the skill mix of graduates was cited as an approach to align with the population needs by 33% of the plans. While education and training are important to many countries, strategic plans should address retention of HRH and continuous quality assurance of personnel through improving the training curricula.

Optimising utilisation, retention and performance of the available health workers

A strategy for attracting professionals and retention of health workers as well as ensuring high-quality service delivery is essential in policy and strategic plan. We scrutinised the plans for factors that will influence attrition and performance of the existing health workers, retain skilled health workers and attract new ones especially to rural areas where demand is often highest. All the plans prioritised improving utilisation, retention and performance of the available health workers (figure 3). The plans particularly emphasised equitable distribution of health workers to rural and hard-to-reach areas and to use incentives to recruit and retain them to those areas. Some (58%) prioritised using financial incentives to improve deployment to rural, difficult to access areas. Only 8% of plans mentioned formally integrating community health workers into the health system in order to meet the shortfall in or to train and integrate them to assure equitable distribution of health workers throughout the country.

Some of the plans (33%) identified the use of performance-based strategies to increase motivation, while 17% of the country plans had established a performance and management system previously to improve the performance of health workers.

Addressing the working conditions and remuneration of health workers was also included in the strategy. However, these plans were not explicit enough as to how they would specifically improve the working conditions and remuneration of health workers. The plans included improving standards of staffing in order to optimise utilisation of health workers, particularly in using the Workload Indicators of Staffing Needs, a WHO tool for determining staffing need at the health facility level.

Although the interventions and polices were based on guidelines, adaptation to country context is unclear.30 31 Countries need to ensure policies improve performance and are tailored to country needs.

Health workforce information and knowledge management

The capacity of many countries to generate, analyse, disseminate and use HRH data for policymaking is still inadequate. Almost all plans (92%) addressed the challenges of improving health workforce information and evidence-informed processes (figure 3). The most common option that countries wanted to employ to address the issue was improving existing human resource information system (HRIS). Only 8% of the countries wanted to assess its HRIS and to scale it up for comprehensively addressing the HRH issues in all health facilities, including those in the private sector. The plans recognised that their respective HRIS was not functioning at optimal capacity. About 17% of the plans stated the need to develop the capacity of human resources to collect, analyse and disseminate results. Half of the plans identified the needs for research and described the plan to establish a health database. Evidence from an HRH database, research and periodic evaluation is an invaluable support for assessing the HRH needs not only by different category of the healthcare system but its distribution across health facilities and the country for meeting the UHC.

Health workforce partnership and dialogue

In SSA countries, policy dialogue among line ministries, stakeholders and partners are limited. Internally mobilised resources are not enough for the requisite production and employment of health workers. Approximately, 73% of the plans mentioned strengthening partnerships and dialogues with various stakeholders in the health workforce (figure 3). A partnership was considered critical to the implementation of strategies and the plans described a wide range of none-state actors, ranging from civil societies, the private sector, academia, professional associations, with which partnership will be developed. Additionally, the policies indicated fostering intersectoral collaboration with other government agencies such as Education, Finance and Public Service whose activities affect HRH issues.

A few (less than 10%) of the plans include developing public–private partnerships for HRH through outsourcing of highly skilled healthcare professionals or through coordinating the use of public health facilities by private training institutions for students’ practicum.

Strengthening health workforce partnership and dialogue seemed to be a priority in many of the plans. Besides the Ministry of Education and training institutions being linked to developing appropriate curricula and training modalities, the plans were not explicit on how a partnership between the two institutions would focus on building capacity and mobilising resources despite its potential influence on harmonising effect on implementation.32 The important role that the professional associations will play in the implementation of the plans should be given prominence in HRH policy and strategic plans.

Conclusion

The WHO roadmap has encouraged the development by African countries, the policy and strategic plans for addressing the dire shortage of human resources for health in the region. This is the first step of laying the foundation and erecting the pillars for building the mainframe for sustainable UHC. The conformity with the roadmap allows a common yardstick for reviewing the progress of each country towards comprehensive healthcare. Comparable HRH policy and strategic plans will make training and exchange of health professionals within the region less challenging. Using these common denominators in spite of the differences in health systems will make deployment across health systems potentially possible and contributes to the much-mouthed integration of African health systems.

With these plans, completed, efforts must be mobilised to encourage investment in the implementation in order to encourage other counties that are yet to finish to complete theirs, while motivating the health systems that have developed these comprehensive policies and strategic plans that will support their attainment of the UHC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the WHO AFRO Country Teams which supported data collection. We appreciate the support from Professor Oladele Akogun in the finalisation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: AA and DO-A analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the initial manuscript. JN contributed to the revising of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors conceptualised and designed the study, collected data and approved the final version of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.WHO A universal truth: no health without workforce. Geneva: WHO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cometto G, Witter S. Tackling health workforce challenges to universal health coverage: setting targets and measuring progress. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:881–5. 10.2471/BLT.13.118810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheil-Adlung X. Health workforce benchmarks for universal health coverage and sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:888–9. 10.2471/BLT.13.126953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes; WHO’s framework for action. Geneva: WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell J. Towards universal health coverage: a health workforce fit for purpose and practice. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:887–8. 10.2471/BLT.13.126698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR, Mercer H, et al. The health worker shortage in Africa: are enough physicians and nurses being trained? Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:225–30. 10.2471/BLT.08.051599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naicker S, Plange-Rhule J, Tutt RC, et al. Shortage of healthcare workers in developing countries-Africa. Ethn Dis 2009;19(Suppl 1):S1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogilvie L, Mill JE, Astle B, et al. The exodus of health professionals from sub-Saharan Africa: balancing human rights and societal needs in the twenty-first century. Nurs Inq 2007;14:114–24. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2007.00358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu JX, Goryakin Y, Maeda A, et al. Global health workforce labor market projections for 2030. Hum Resour Health 2017;15 10.1186/s12960-017-0187-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrinho P, Siziya S, Goma F, et al. The human resource for health situation in Zambia: deficit and maldistribution. Hum Resour Health 2011;9 10.1186/1478-4491-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyoni J, Gbary A, Awases M, et al. Policies and plans for human resources for health: guidelines for countries in the WHO African region. Human Resources Observer Issue 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mugisha J, Abdulmalik J, Hanlon C, et al. Health systems context(s) for integrating mental health into primary health care in six Emerald countries: a situation analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst 2017;11 10.1186/s13033-016-0114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Road map for scaling up the human resources for health: for improved health service delivery in the African region 2012-2025. Brazzaville: WHO AFRO, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyoni J, Gedik G. Health workforce governance and leadership capacity in the African region: review of human resources for health units in the ministries of health. Hum Resour Health Obs 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fieno JV, Dambisya YM, George G, et al. A political economy analysis of human resources for health (HRH) in Africa. Hum Resour Health 2016;14 10.1186/s12960-016-0137-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cailhol J, Craveiro I, Madede T, et al. Analysis of human resources for health strategies and policies in 5 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in response to GFATM and PEPFAR-funded HIV-activities. Global Health 2013;9 10.1186/1744-8603-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martineau T, Caffrey M. Human Resources for Health (HRH) Strategic Planning: Capacity Project 2008. Available: https://www.intrahealth.org/sites/ihweb/files/files/media/human-resources-for-health-strategic-planning/techbrief_9.pdf [Accessed 12 Dec 2016].

- 18.Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, et al. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:853–63. 10.2471/BLT.13.118729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Framing the health workforce agenda for the sustainable development goals: biennium report 2016-2017-WHO health workforce. Geneva: WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adeloye D, David RA, Olaogun AA, et al. Health workforce and governance: the crisis in Nigeria. Hum Resour Health 2017;15 10.1186/s12960-017-0205-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingue S, Rosskam E, Bela AC, et al. Strengthening human resources for health through multisectoral approaches and leadership: the case of Cameroon. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:864–7. 10.2471/BLT.13.127829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Pas R, Veenstra A, Gulati D, et al. Tracing the policy implementation of commitments made by National governments and other entities at the third global Forum on human resources for health. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000456 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo G, Pavignani E, Guerreiro CS, et al. Can we halt health workforce deterioration in failed States? Insights from Guinea-Bissau on the nature, persistence and evolution of its HRH crisis. Hum Resour Health 2017;15 10.1186/s12960-017-0189-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dieleman M, Shaw DM, Zwanikken P. Improving the implementation of health workforce policies through governance: a review of case studies. Hum Resour Health 2011;9 10.1186/1478-4491-9-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broek A, Gedik G, Dal Poz M, et al. Policies and practices of countries that are experiencing a crisis in human resources for health: tracking analysis. Hum Resour Health Obs 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell J, Jones I, Whyms D. "More money for health - more health for the money": a human resources for health perspective. Hum Resour Health 2011;9 10.1186/1478-4491-9-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO, Health Workforce 2030: Towards a global strategy on human resources for health. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy CF, Voss J, Salmon ME, et al. Nursing and midwifery regulatory reform in East, central, and southern Africa: a survey of key stakeholders. Hum Resour Health 2013;11 10.1186/1478-4491-11-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown A, Cometto G, Cumbi A, et al. Mid-level health providers: a promising resource. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 2011;28:308–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolea C, Stormont L, Braichet J-M. Evaluated strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:379–85. 10.2471/BLT.09.070607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witter S, Fretheim A, Kessy FL, et al. Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(2). 10.1002/14651858.CD007899.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nabyonga-Orem J, Ousman K, Estrelli Y, et al. Perspectives on health policy dialogue: definition, perceived importance and coordination. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16(Suppl 4). 10.1186/s12913-016-1451-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2018-001115supp001.pdf (75.4KB, pdf)