Abstract

Objectives

To keep healthcare systems sustainable for future demands, many countries are developing a centralised telephone line for out-of-hours primary care services. To increase the quality of such services, more information is needed on factors that influence caller satisfaction. The aim of this study was to identify demographic and call-related characteristics that are associated with the patient satisfaction of callers to a medical helpline in Denmark.

Design

Retrospective cohort study on patient registry data and questionnaire results.

Setting

Non-emergency medical helpline in the Capital Region of Denmark.

Participants

A random sample of 30 402 callers to the medical helpline between May 2016 and May 2018.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Responses of a satisfaction questionnaire were linked to demographic and call-related dispatch data. Associations between the characteristics were analysed with multivariable logistic regression analysis with satisfaction as the dependent variable. A subgroup analysis was performed on callers for children aged between 0 and 4 years.

Results

Of the 30 402 analysed callers, 73.0% were satisfied with the medical helpline. Satisfaction was associated with calling for a somatic injury (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.72 to 2.23), receiving a face-to-face consultation (OR: 2.27, 95% CI: 2.04 to 2.50) and a waiting time less than 10 min (OR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.56 to 2.08). Callers for a 0-year to 4-year-old patient were more likely to be satisfied when they called for a somatic illness or received a telephone consultation, compared with the rest of the population (p<0.0001).

Conclusion

Callers were in general satisfied with the medical helpline. Satisfaction was associated with reason for encounter, triage response and waiting time. People calling for 0-year to 4-year-old patients were, compared with the rest of the population, more frequently satisfied when they called for a somatic illness or received a telephone consultation.

Keywords: out-of-hours healthcare, patient satisfaction, telephone triage, Denmark

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The satisfaction questionnaire ran over a 2-year period, which ensured a large sample size (n=30 402) and allowed for conducting a subgroup analysis.

The short length of the questionnaire enabled people to respond who would normally not respond to long questionnaires, such as parents of children or patients with a psychiatric illness.

Responses to the satisfaction questionnaire were linked to internal patient registry data, which provided more information on the characteristics of the respondents.

Although data on non-receivers of the questionnaire were analysed, the analysis was limited because characteristics of non-respondents could not be obtained due to regulations around patient data protection.

Introduction

Member States of the European Union (EU) face growing and changing healthcare needs due to population ageing and tight budgetary constraints.1 To keep the healthcare systems sustainable for the future, EU countries are working on initiatives towards more integrated care models.2 More integrated and people-centred healthcare systems are expected to provide services that are of better quality, financially more sustainable and more responsive to personal preferences and needs.3–5 One way to make the healthcare provision more integrated is to vertically integrate the primary and secondary healthcare services.2 Hence, many EU countries are working on initiatives to change the out-of-hours (OOH) pre-hospital care towards a closer collaboration between the general practitioners (GPs) and hospital emergency departments. This can be done by establishing national telephone numbers that centralise the OOH calls and triage.6

Such an OOH telephone line has been established in Copenhagen. The aim of this so-called 1813 medical helpline is to provide always available easy access to healthcare, and at the same time relieve the pressure on the hospital emergency departments.7 8 An OOH telephone triage system may reduce GP visits and the immediate medical workload.9–11 Yet, to increase the effectiveness of the system, more detailed information is needed on several aspects of the system, among which patient satisfaction.9 This is a desired outcome of care, incorporating interpersonal relationships, specific components of technical care and the outcomes of care.12 Analysing patient satisfaction scores can provide information about whether interventions result in better outcomes from the perspective of the patient, and consequently improve the quality of patient-centred healthcare systems.13 Since patients’ level of satisfaction depends on many factors, including demographic factors, call-specific experiences and expectations,14–17 constant monitoring of satisfaction in various settings is required.

Therefore, a continuously running questionnaire was established to monitor the patient satisfaction of the callers to the 1813 medical helpline of the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Copenhagen on a structural basis. The aim of this study was to use the questionnaire to identify the demographic and call-related characteristics that are associated with the reported patient satisfaction of the callers to this medical helpline. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis was performed on calls concerning 0-year to 4-year-old children because of the frequent use of the medical helpline for this group.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective cohort study was performed on the 1813 medical helpline for non-emergency OOH calls to the EMS Copenhagen. Outside GP working hours (between 16:00 and 08:00 on weekdays, in weekends and during holidays), the 1.8 million citizens of the region can call two telephone numbers when they have health issues.18 19 They can dial 112 to reach the Emergency Medical Dispatch Centre (EMDC-112) for emergency situations and for the less urgent, not life-threatening health problems the 1813 medical helpline.20 This medical helpline handles on average 924 000 calls a year, of which most are answered by triage nurses.7 They pre-assess the need for the caller to access acute medical help, which makes them play a dominant role in gatekeeping the healthcare system.21 22 The triage nurses can respond with several actions such as booking an appointment at an acute admission centre, emergency clinic or psychiatric admission centre, forward the call to the EMDC-112 or a doctor, plan a home visit, recommend the patient to contact the GP on the next working day or give telephone advice for self-care.19 21

Every day, 200 callers of the previous day were selected by a simple random sampling method23 and sent a text message to the phone number they called the medical helpline with. The text message comprised two questions: ‘Are you overall satisfied with the contact you had with the medical helpline 1813?’, and ‘Were your questions answered during the contact with the medical helpline 1813?’. The callers were asked to answer those questions on a five-point Likert scale answer category, containing: ‘to a great extent’, ‘to a large extent’, ‘to a moderate extent’, ‘to a limited extent’ or ‘not at all’. Furthermore, they had the option to answer: ‘not applicable’ or ‘don’t know’.

Data collection and processing

Data were collected via two data sources: the patient satisfaction questionnaire and internal patient registration that provided data on gender, age, reason for encounter, triage response, time of the call, waiting time, consultation time and profession of the call-handler(s). Patients were included if they called the medical helpline between 18 May 2016 and 30 April 2018. Patients who were referred to the medical helpline after calling EMDC-112 were excluded for selection, because from them there were no telephone numbers available in the system. Permission from individual patients is not required for this type of study in Denmark. A request was sent to the Research Ethics Committee in the Capital Region of Denmark, but approval was not needed for this study (J.number 19042590). However, based on ethical considerations, patients were excluded if they were sent a questionnaire but failed to respond. Callers were also excluded when they answered ‘not applicable’ or ‘don’t know’ to the first question about their satisfaction, since it was outside the scope of the study. Call observations were removed when the call lasted less than 15 s or when the patient’s age did not range between 0 and 100 years (caused by errors in the patient registration).

For the descriptive analyses, respondents were classified according to the satisfaction question of the questionnaire into satisfied (‘to a great extent’ or ‘to a large extent’), intermediate (‘to a moderate extent’) and dissatisfied (‘to a limited extent’ or ‘not at all’). Patients’ age was categorised into six groups (<5, 5–17, 18–39, 40–59, 60–79 and ≥80 years), based on the pattern of disease and the organisation of the system where children (0-year to 18-year old) sometimes receive a face-to-face consultation at another department of the hospital. Other variables that were categorised are as follows: reason for encounter (somatic illness, somatic injury, psychiatric illness or other), triage response (face-to-face consultation, telephone consultation, ambulance dispatch or other), time of the call (daytime weekday, daytime OOH and evening/night OOH), waiting time (<3, 3–6, 6–10, 10–20 and ≥20 min, later categorised into 0–10, 10–20 and ≥20 min) and consultation time (<3, 3–6, 6–10 and ≥10 min, later dichotomised into <6 min and ≥6 min). The profession of the first call-taker could be nurse, physician, priority physician (answers prioritised calls from healthcare facilities) and EMDC-112-dispatcher.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the patients’ characteristics with frequencies (number, percentage) and median values (Q1–Q3). The representativeness of the respondents for the total population was determined by first estimating the characteristics of the non-respondents by assuming the same proportions among receivers and non-receivers. Subsequently, the proportions of the non-respondents were estimated by subtracting the number of respondents from this total estimated numbers of receivers. Differences in characteristics between the satisfied and dissatisfied respondents were calculated with χ2 tests. The association between the patients’ characteristics and satisfaction was analysed using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. Here, the satisfied respondents were compared with the dissatisfied respondents, which left the intermediate group of respondents out of the analyses. Results of these analyses were reported in ORs and 95% CI. For the multivariable analysis, a full fitted model without a selection was created, since there was no solid evidence available in previously published scientific literature about potential relevant variables. Variables that were entered to the model were as follows: gender, age, reason for encounter, triage response, time of the call, waiting time, consultation time, profession of first call-taker and being forwarded to a physician. Thereafter, a subgroup analysis was performed to analyse the characteristics of the satisfied callers for 0-year to 4-year-old children, who were relatively frequent callers based on the distribution of the population by age in the Copenhagen region. Another univariable analysis comparing the proportion of satisfied callers for 0-year to 4-year-old children with the rest of the population was performed with the variables that were found to be statistically significant in the multivariable analysis. Statistical significance was based on an alpha error of 0.05 and data was analysed with SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

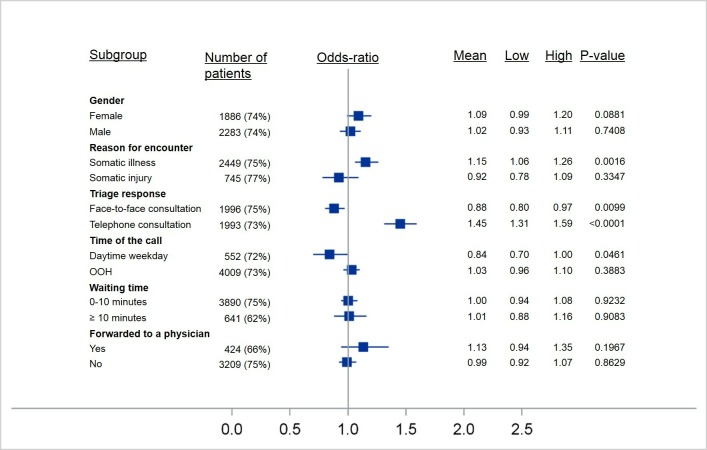

Of the 1 843 094 calls during the study period, 1 731 556 calls were eligible (figure 1). Among those were 30 402 respondents (response rate: 23.0%). The majority of the calls concerned females (54.8%) and the median age was 29 (11–53). Most of the calls were related to somatic illnesses (64.0%), followed by somatic injuries (26.9%). A face-to-face consultation was offered to 46.8% of the callers and 42.6% received a telephone consultation. Most of the calls were picked up by a nurse (75.7%) and 14.6% of those were forwarded to a physician.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the included study population.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the respondents, divided into satisfied, intermediate and dissatisfied respondents, and those of the non-receivers. On all tested characteristics, the respondents differed from the non-receivers (p<0.0001). Assuming that the receivers of the questionnaire have the same proportions of characteristics as the non-receivers, the respondents were less often older than 80 years (2.4% vs 7.9%), called more often for a somatic injury (24.4% vs 17.4%) and received more often a face-to-face consultation (53.3% vs 43.0%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents and non-receivers and the estimated difference between respondents and non-respondents

| Respondents (n=30 402) |

Non-receivers (n=1701154) |

Difference % respondents versus % estimation non-respondents | |||

| Satisfied (n=22 203) |

Intermediate (n=5002) | Dissatisfied (n=3197) |

|||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 12 103 (54.5%) | 2824 (56.5%) | 1723 (53.9%) | 901 247 (53.0%) | 2.5% |

| Male | 9738 (43.9%) | 2064 (41.3%) | 1372 (42.9%) | 742 677 (43.7%) | −0.3% |

| Missing | 362 (1.6%) | 114 (2.3%) | 102 (3.2%) | 57 230 (3.4%) | −1.9% |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0–4 | 4169 (18.8%) | 947 (18.9%) | 509 (15.9%) | 278 601 (16.4%) | 2.8% |

| 5–17 | 4116 (18.5%) | 865 (17.3%) | 440 (13.8%) | 230 482 (13.6%) | 5.6% |

| 18–39 | 5350 (24.1%) | 1510 (30.2%) | 1182 (37.0%) | 518 393 (30.5%) | −5.2% |

| 40–59 | 4689 (21.1%) | 997 (19.9%) | 669 (20.9%) | 294 642 (17.3%) | 5.5% |

| 60–79 | 2942 (13.3%) | 475 (9.5%) | 241 (7.5%) | 208 682 (12.3%) | −0.3% |

| ≥80 | 575 (2.6%) | 94 (1.9%) | 54 (1.7%) | 113 127 (6.7%) | −5.5% |

| Missing | 362 (1.6%) | 114 (2.3%) | 102 (3.2%) | 57 227 (3.4%) | 4.0% |

| Reason for encounter | |||||

| Somatic illness | 10 533 (47.4%) | 2374 (47.5%) | 1599 (50.0%) | 773 868 (45.5%) | 3.0% |

| Somatic injury | 5977 (26.9%) | 1043 (20.9%) | 412 (12.9%) | 324 253 (19.1%) | 7.0% |

| Psychiatric illness | 92 (0.4%) | 25 (0.5%) | 12 (0.4%) | 10 842 (0.6%) | −0.3% |

| Other * | 5601 (25.2%) | 1560 (31.2%) | 1174 (36.7%) | 592 191 (34.8%) | −9.5% |

| Triage response | |||||

| Face-to-face consultation | 12 527 (56.4%) | 2546 (50.9%) | 1121 (35.1%) | 772 583 (45.4%) | 10.3% |

| Telephone consultation | 7437 (33.5%) | 1996 (39.9%) | 1644 (51.4%) | 706 467 (41.5%) | −6.5% |

| Ambulance | 1027 (4.6%) | 97 (1.9%) | 36 (1.1%) | 54 071 (3.2%) | 0.8% |

| Other* | 1212 (5.5%) | 363 (7.3%) | 396 (12.4%) | 168 033 (9.9%) | −4.4% |

| Time of the call | |||||

| Daytime weekday | 3353 (15.1%) | 682 (13.6%) | 480 (15.0%) | 216 978 (12.8%) | 2.8% |

| Daytime OOH | 3606 (16.2%) | 928 (18.6%) | 541 (16.9%) | 409 131 (24.1%) | −9.5% |

| Evening/night OOH | 15 244 (68.7%) | 3392 (67.8%) | 2176 (68.1%) | 1 075 045 (63.2%) | 7.0% |

| Waiting time | |||||

| 0–3 min | 11 989 (54.0%) | 2175 (43.5%) | 1397 (43.7%) | 860 874 (50.6%) | 0.9% |

| 3–6 min | 3904 (17.6%) | 772 (15.4%) | 558 (17.5%) | 286 752 (16.9%) | 0.5% |

| 6–10 min | 3057 (13.8%) | 742 (14.8%) | 445 (13.9%) | 235 531 (13.9%) | 0.2% |

| 10–20 min | 2649 (11.9%) | 933 (18.7%) | 556 (17.4%) | 240 072 (14.1%) | −0.6% |

| ≥20 min | 604 (2.7%) | 380 (7.6%) | 241 (7.5%) | 77 914 (4.6%) | −0.7% |

| Consultation time | |||||

| 0–3 min | 7919 (35.7%) | 1896 (37.9%) | 1268 (39.7%) | 641 846 (37.7%) | −1.6% |

| 3–6 min | 10 134 (45.6%) | 2234 (44.7%) | 1334 (41.7%) | 740 206 (43.5%) | 2.1% |

| 6–10 min | 3505 (15.6%) | 742 (14.8%) | 517 (16.2%) | 264 892 (15.6%) | 0.2% |

| ≥10 min | 645 (2.9%) | 130 (2.6%) | 78 (2.4%) | 54 210 (3.2%) | −0.5% |

| First call-taker | |||||

| Nurse | 17 654 (79.5%) | 3838 (76.7%) | 2406 (75.3%) | 1 265 043 (74.4%) | 5.7% |

| Physician | 3942 (17.8%) | 1042 (20.8%) | 699 (21.9%) | 388 509 (22.8%) | −5.3% |

| Priority physician | 125 (0.6%) | 32 (0.6%) | 35 (1.1%) | 20 527 (1.2%) | −0.7% |

| 112 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (0.0%) | 0.0% |

| Missing | 482 (2.2%) | 90 (1.8%) | 57 (1.8%) | 27 063 (1.6%) | 0.6% |

| Call forwarded to a physician† | |||||

| Yes | 2073 (11.7%) | 675 (17.6%) | 489 (20.3%) | 184 250 (14.6%) | 0.4% |

| No | 15 581 (88.3%) | 3163 (82.4%) | 1917 (79.7%) | 1 080 743 (85.4%) | −0.4% |

*Includes missing values.

†Percentage based on the number of calls that were in first instance picked up by a nurse.

OOH, out-of-hours.

Patient satisfaction

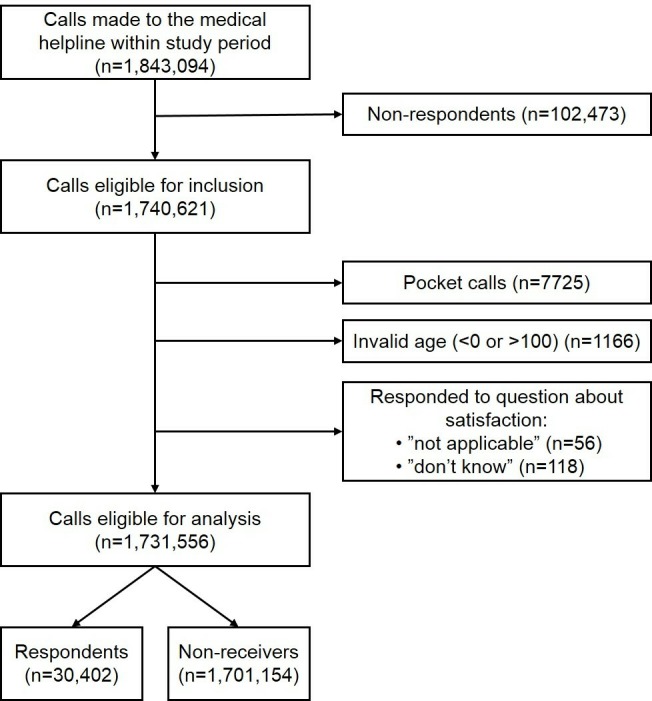

A total of 22 203 respondents (73.4%) indicated to be satisfied with their encounter with the medical helpline (‘to a great extent’: 43.3%; ‘to a large extent’: 30.1%). Another 4894 respondents replied ‘to a moderate extent’ (16.3%) and 3097 (10.3%) indicated to be dissatisfied (‘to a limited extent’: 5.3%; ‘not at all’: 5.0%) (figure 2). To the second question about whether the callers received an answer to their question, 71.7% replied at least ‘to a large extent’ and 1.2% replied ‘don’t know/not applicable’. More than half of the respondents (63.5%) gave the same answers to both questions. Of those who indicated to be satisfied with the service, 65.2% replied to be given an answer at least ‘to a large extent’ to their question.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the responses to the patient satisfaction questionnaire.

The satisfied respondents differed on all tested characteristics from the dissatisfied respondents (p<0.0001), except for gender and time of the call. Among others, the satisfied respondents concerned more often patients aged <5 years old and ≥60 years old (table 1). Furthermore, respondents who called for a somatic illness were less often satisfied than respondents calling for a somatic injury (72.6% vs 80.4%). People who received a face-to-face consultation or ambulance where more often satisfied (77.4% and 88.5%, respectively) than patients who ended up with a telephone consultation (67.1%). The median waiting time of the satisfied respondents was almost 1.5 min shorter than that of the dissatisfied respondents (2:30 min vs 4:05 min). Of the people who had a waiting time longer than 20 min, 49.3% were satisfied and of those who talked to a physician, 67.4% were satisfied.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis

Calling for a somatic injury was statistically significantly associated with satisfaction (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.72 to 2.23). People who received a telephone consultation were less likely to be satisfied (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.49). People were also less likely to be satisfied when they had a waiting time of more than 10 min (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.48 to 0.64) and especially a waiting time more than 20 min (OR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.30). No statistically significant association was seen between consultation time and satisfaction. In the univariable analysis, the profession of the first call-taker was associated with satisfaction. Adding the variable to the multivariable model did not have an effect. Yet, people who were forwarded to a physician were less likely to be satisfied (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.78) (table 2).

Table 2.

Likelihood (OR) of satisfaction for different demographic and call-related characteristics

| Crude OR (95% CI) n=19 476† | Adjusted OR (95% CI) n=16 307† | |

| Gender | ||

| Female (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.93)* |

| Age (years) | ||

| 0–4 | 1.81 (1.62 to 2.02) | 2.21 (1.90 to 2.57)* |

| 5–17 | 2.07 (1.84 to 2.32) | 1.93 (1.65 to 2.26)* |

| 18–39 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 40–59 | 1.55 (1.40 to 1.72) | 1.42 (1.23 to 1.63)* |

| 60–79 | 2.70 (2.33 to 3.12) | 2.82 (2.29 to 3.49)* |

| ≥80 | 2.35 (1.77 to 3.13) | 2.35 (1.49 to 3.68)* |

| Reason for encounter | ||

| Somatic illness (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Somatic injury | 2.20 (1.97 to 2.47) | 1.96 (1.72 to 2.23)* |

| Triage response | ||

| Face-to-face consultation (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Telephone consultation | 0.40 (0.37 to 0.44) | 0.44 (0.40 to 0.49)* |

| Time of the call | ||

| Daytime weekday | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) | 0.65 (0.54 to 0.78)* |

| Daytime OOH (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Evening/night OOH | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16) | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.09) |

| Waiting time | ||

| 0–10 min (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 10–20 min | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.67) | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.64)* |

| ≥20 min | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.37) | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.30)* |

| Consultation time | ||

| 0–6 min (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥6 min | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.11) | 1.08 (0.95 to 1.23) |

| First call-taker | ||

| Nurse (ref) | 1 | |

| Physician | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.83) | |

| Call forwarded to a physician | ||

| Yes | 0.52 (0.47 to 0.58) | 0.68 (0.58 to 0.78)* |

| No (ref) | 1 | 1 |

*P value<0.05.

†The lowest amount of observations in the models.

OOH, out-of-hours.

0-year to 4-year-old subgroup analysis

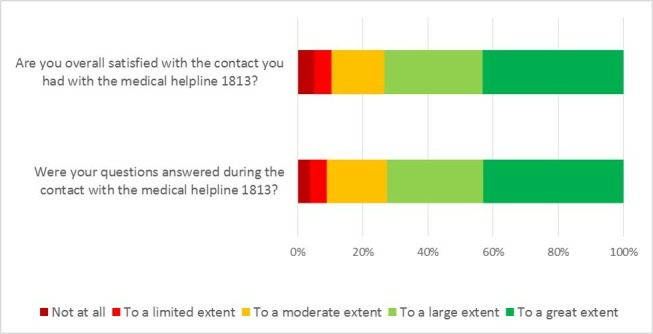

On average 74.1% of the respondents calling for a 0-year to 4-year-old child were satisfied, compared with 73.0% of the rest of the population. Although averages in satisfaction fluctuated per month, the overall satisfaction rate of people calling for a 0-year to 4-year-old child was stable over time (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Total number and percentage of satisfied respondents calling for a 0-year to 4 -year-old patient per month.

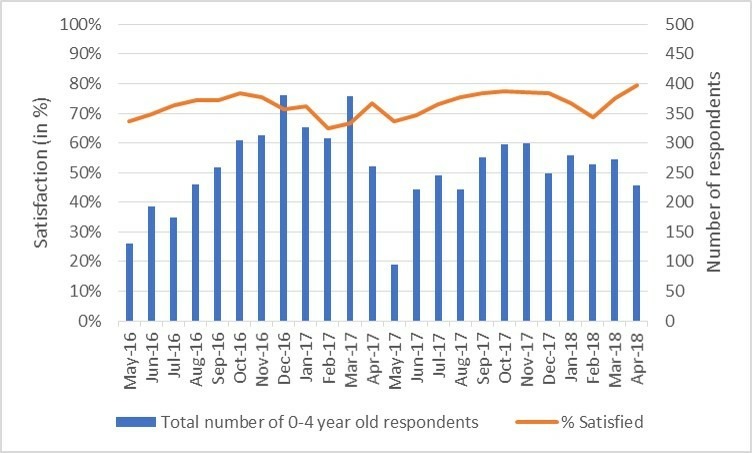

As shown in figure 4, callers for 0-year to 4-year-old children were more likely to be satisfied when they called for a somatic illness (OR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.26) and received a telephone consultation (OR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.31 to 1.59). They were less likely to be satisfied when they received a face-to-face consultation (OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.80 to 0.97) and called during GP office hours (OR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.70 to 1.00).

Figure 4.

OR and 95% CI for demographic and call-related characteristics predicting satisfaction for 0-year to 4-year-old patients compared with 5-year to 100-year-old patients figure 4.

Discussion

This study has indicated that caller satisfaction with the OOH medical helpline was significantly associated with gender, age, reason for encounter, triage response and waiting time. Furthermore, people who called during GP office hours were less likely to be satisfied than people calling OOH. People calling on behalf of a 0-year to 4-year-old child were more likely to be satisfied compared with the rest of the population, when they called for a somatic illness and when they received a telephone consultation, but less likely to be satisfied when they received a face-to-face consultation and called during GP office hours.

The satisfaction rate of 73% is in line with findings from previous studies.14 24–26 Also, the other findings of this study were generally in accordance with previous studies, which showed associations between (dis)satisfaction and patient gender,27 age,28 call reason,26 triage response14 16 29 and waiting time.14 15 27 Whereas another study also found an association with consultation length,15 this was not found in our study. This same study on a telephone service in Wales also found that patients who received a telephone consultation were more satisfied than patients who received a face-to-face consultation, which contradicts our findings as well.15 The multivariable analysis also showed that people whose call was forwarded to a physician were less likely to be satisfied. This might have been induced by the reason why the call was forwarded in the first place, which were probably the more complex calls. Besides, it could have been influenced by a difference in expectation callers had about their call-taker.

Our study’s finding that people who call for 0-year to 4-year-old children were on certain characteristics more likely to be satisfied compared with the rest of the population could be explained by different expectations of callers. Studies have shown that a mismatch between a caller’s request or expectation and triage outcome is associated with lower patient satisfaction.30–32 The findings of this study also indicate that subgroup analyses regarding determinants of satisfaction can be useful to design tailored quality improvement interventions of the OOH healthcare services.

The main strengths of this study were the long running time of the questionnaire on a daily basis, and the opportunity to link responses to internal patient registry data. This provided relevant information about the respondents’ characteristics. In addition, the length of the questionnaire makes this study unique from other patient satisfaction studies, where often longer questionnaires are held.14–16 27 28 The major benefit of this short questionnaire is that it increased the feasibility of the study, since it is durable and easy to fill in. People who normally do not have the time or the resources to fill in a long questionnaire did respond to this one. Examples are parents of young children and patients with a psychiatric illness. The long running period of this questionnaire benefited the internal validity of the study, as it showed stable satisfaction rates over time. The short period between the contact with the medical helpline and the delivery of the questionnaire to the caller’s phone reduced the risk of recall bias.

However, the study was limited by the low response rate, the way the questionnaire was distributed and the form of the questionnaire. The low response rate and the fact that the questionnaire could not be sent to analogue telephones may have induced a selection bias by self-selection of people who responded to the questionnaire. When estimating the characteristics of the non-respondents, it seemed that respondents were less often older than 80 years, called more often for a somatic injury and received more often a face-to-face consultation. Yet, the relevance of these estimated differences may be doubted. A study from the Netherlands that interviewed non-respondents of an OOH GP cooperative questionnaire found that most non-respondents gave reasons for not responding that were not directly related to their contact with the GP cooperative.16 The way the questionnaire was distributed also limited the study because the respondent might not have been the patient to whom the answers were linked. That means that the caller could have other demographic characteristics than was assumed in this study. This is especially a relevant limitation for the analysis of the callers for the 0-year to 4-year-old patients. The short length of the questionnaire limits the study because of the difficulty to capture the dimensions of the whole service in two multiple choice questions. The analysis also showed that 64% of the respondents gave the same answers to both questions, which raises concern about the validity of the second question. Furthermore, this study did not include all determinants of satisfaction, such as self-perceived (improvement in) health.14 27 28

Further studies could gather more insight about the reasons behind the satisfaction for the particular characteristics of the subgroup of callers for 0-year to 4-year-old children. This, in turn, could assist tailored-made conversation and decision support for the medical staff of the medical helpline to improve the service to all patients, who call for help and guidance.

Conclusions

This study showed that people are in general satisfied with an OOH medical helpline. Satisfaction was associated with calling for a somatic injury, being offered a face-to-face consultation, and having a short waiting time on the phone. People calling for 0-year to 4-year-old patients are more likely to be satisfied compared with the rest of the population when they call for a somatic illness and receive a telephone consultation. This study also showed that a text message with a short questionnaire is feasible to run on a daily basis and that it can provide valuable information for structural quality monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NDZ, SNB, FL and HCC contributed to the design and implementation of the research. NDZ performed the analysis and SNB, FL and HCC aided in interpreting the results. NDZ and SNB designed the figures. NDZ wrote the paper in consultation with FL and HCC. HCC supervised the work.

Funding: This study was supported by an unrestricted grant from The Laerdal Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development / European Union Health at a glance: Europe 2016 – state of health in the EU cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Commission State of health in the EU companion report 2017. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization WHO global strategy on people-centered and integrated health services: interim report. Geneva, 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/155002/WHO_HIS_SDS_2015.6_eng.pdf

- 4. Hwang W, Chang J, Laclair M, et al. Effects of integrated delivery system on cost and quality. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:e175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Machta RM, Maurer KA, Jones DJ, et al. A systematic review of vertical integration and quality of care, efficiency, and patient-centered outcomes. Health Care Manage Rev 2019;44:159–73. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huibers L, Giesen P, Wensing M, et al. Out-of-hours care in Western countries: assessment of different organizational models. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:105 10.1186/1472-6963-9-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Folketinget S. Rigsrevisionens beretning om Region Hovedstadens akkuttelefon 1813 afgivet til Folketinget med Statsrevisorernes bemærkninger [Rigsrevisionen’s report on the 1813 set up by the Capital Region of Denmark submitted to the Public Accounts Committee. Copenhagen: Rosendahls Lager og Logistik: 978-87-7434-522-0, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Primary care in Denmark, OECD reviews of health systems. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bunn F, Byrne G, Kendall S, et al. Telephone consultation and triage: effects on health care use and patient satisfaction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;23:CD004180 10.1002/14651858.CD004180.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ismail SA, Gibbons DC, Gnani S. Reducing inappropriate accident and emergency department attendances: a systematic review of primary care service interventions. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e813–20. 10.3399/bjgp13X675395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leibowitz R, Day S, Dunt D. A systematic review of the effect of different models of after-hours primary medical care services on clinical outcome, medical workload, and patient and GP satisfaction. Fam Pract 2003;20:311–7. 10.1093/fampra/cmg313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743–8. 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kleefstra SM, Zandbelt LC, de Haes HJCJM, et al. Trends in patient satisfaction in Dutch University medical centers: room for improvement for all. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:112 10.1186/s12913-015-0766-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tranberg M, Vedsted P, Bech BH, et al. Factors associated with low patient satisfaction in out-of-hours primary care in Denmark - a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:15 10.1186/s12875-017-0681-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kelly M, Egbunike JN, Kinnersley P, et al. Delays in response and triage times reduce patient satisfaction and enablement after using out-of-hours services. Fam Pract 2010;27:652–63. 10.1093/fampra/cmq057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Uden CJT, Ament AJHA, Hobma SO, et al. Patient satisfaction with out-of-hours primary care in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 2005;5:6 10.1186/1472-6963-5-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li L, Georgiou A, Xiong J, et al. Healthdirect's after hours GP helpline - a survey of patient satisfaction with the service and compliance with advice. Stud Health Technol Inform 2016;227:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henriksen DP, Rasmussen L, Hansen MR, et al. Comparison of the Five Danish Regions Regarding Demographic Characteristics, Healthcare Utilization, and Medication Use--A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140197 10.1371/journal.pone.0140197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ebert JF, Huibers L, Lippert FK, et al. Development and evaluation of an ‘emergency access button’ in Danish out-of-hours primary care: a study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:379 10.1186/s12913-017-2308-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Region Hovedstaden Akuthjælpsfolder [Critical care services leaflet]. Available: https://www.regionh.dk/english/Healthcare-Services/Emergency-Medical-Services/Documents/1813%20Akuthjælpsfolder_UK.pdf [Accessed 26 Apr 2018].

- 21. Gamst-Jensen H, Huibers L, Pedersen K, et al. Self-rated worry in acute care telephone triage: a mixed-methods study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e197–203. 10.3399/bjgp18X695021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Møller TP, Ersbøll AK, Tolstrup JS, et al. Why and when citizens call for emergency help: an observational study of 211,193 medical emergency calls. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2015;23:88 10.1186/s13049-015-0169-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martínez-Mesa J, González-Chica DA, Duquia RP, et al. Sampling: how to select participants in my research study? An Bras Dermatol 2016;91:326–30. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. García-Alfranca F, Puig A, Galup C, et al. Patient satisfaction with pre-hospital emergency services. A qualitative study comparing professionals' and patients' views. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:E233 10.3390/ijerph15020233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Riiskjaer E, Ammentorp J, Nielsen JF, et al. Patient surveys – a key to organizational change? Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:394–401. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LaVela SL, Gering J, Schectman G, et al. Optimizing primary care telephone access and patient satisfaction. Eval Health Prof 2012;35:77–86. 10.1177/0163278711411479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abolfotouh MA, Al-Assiri MH, Alshahrani RT, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction in an emergency care centre in central Saudi Arabia: a prospective study. Emerg Med J 2017;34:27–33. 10.1136/emermed-2015-204954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Danielsen K, Bjertnaes OA, Garratt A, et al. The association between demographic factors, user reported experiences and user satisfaction: results from three casualty clinics in Norway. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:73 10.1186/1471-2296-11-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moll van Charante E, Giesen P, Mokkink H, et al. Patient satisfaction with large-scale out-of-hours primary health care in the Netherlands: development of a postal questionnaire. Fam Pract 2006;23:437–43. 10.1093/fampra/cml017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stokoe E, Sikveland RO, Symonds J. Calling the GP surgery: patient burden, patient satisfaction, and implications for training. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e779–85. 10.3399/bjgp16X686653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKinley RK, Stevenson K, Adams S, et al. Meeting patient expectations of care: the major determinant of satisfaction with out-of-hours primary medical care? Fam Pract 2002;19:333–8. 10.1093/fampra/19.4.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bleich SN, Özaltin E, Murray CKL. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:271–8. 10.2471/BLT.07.050401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.