Abstract

Regulation of RNA homeostasis or “RNAstasis” is a central step in eukaryotic gene expression. From transcription to decay, cellular messenger RNAs (mRNAs) associate with specific proteins in order to regulate their entire cycle, including mRNA localization, translation and degradation, among others. The best characterized of such RNA-protein complexes, today named membraneless organelles, are Stress Granules (SGs) and Processing Bodies (PBs) which are involved in RNA storage and RNA decay/storage, respectively. Given that SGs and PBs are generally associated with repression of gene expression, viruses have evolved different mechanisms to counteract their assembly or to use them in their favor to successfully replicate within the host environment. In this review we summarize the current knowledge about the viral regulation of SGs and PBs, which could be a potential novel target for the development of broad-spectrum antiviral therapies.

Keywords: RNAstasis, RNA granules, membraneless organelles, stress granules, P-Bodies, anti-viral host immune response

Introduction

RNA plays key roles in all biological systems where RNAstasis is a central processing unit in the regulation of gene expression in eukaryotic cells (Sharp, 2009). RNAstasis include synthesis, modification, protection, storage, release, transportation and degradation of different types of RNA (mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, siRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, piRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, smRNA) and metabolic processes mediated by RNA–protein complexes called RNA granules. Depending on its localization, RNA granules are found in the nucleus, in the nucleolus, paraspeckles, nuclear speckles and Cajal bodies; or in the cytoplasm, as stress granules (SGs) and processing bodies (PBs). All are membraneless organelles (i.e., lack an enclosing membrane, MLOs) to allow for rapid exchange of components with the surrounding cellular environment (Fay and Anderson, 2018). MLOs contain a heterogeneous mixture of nucleic acids and proteins that present low-complexity regions (LCRs) and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) regulated by post-translational modifications (Ramaswami et al., 2013; Panas et al., 2016; Wheeler et al., 2016). MLO biogenesis has been shown to be via liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) process, supporting the high flexibility and quick adaptive responses to environmental stresses required for function (reviewed in Fay and Anderson, 2018).

After several rounds of translation, an mRNA undergoes degradation as a way of turnover. Indeed, it is suggested that mRNA degradation is tightly dependent on translation (Bicknell and Ricci, 2017).

However, under conditions of cellular stress, the cell responds by mounting a robust response causing the shutoff of protein synthesis in order to protect the mRNA so that translation can resume once the stress disappears. Repression of gene expression induces the assembly of RNA granules such as SGs and PBs, which are involved in mRNA triage and untranslated mRNA storage, respectively. By using single mRNA imaging in living human cells, it has been recently reported that a single mRNA can interact with both SGs and PBs (Wilbertz et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2019). However, while Wilbertz et al. showed that an mRNA preferably moves from a SG to a PB, Moon et al. showed a dynamic and bidirectional exchange of a single mRNA to multiple SGs and PBs (Wilbertz et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2019). Despite their distinctive organization and unique molecular markers, SGs and PBs share molecular components which could allow the dynamic shuttling of an mRNA between them (Kedersha et al., 2005).

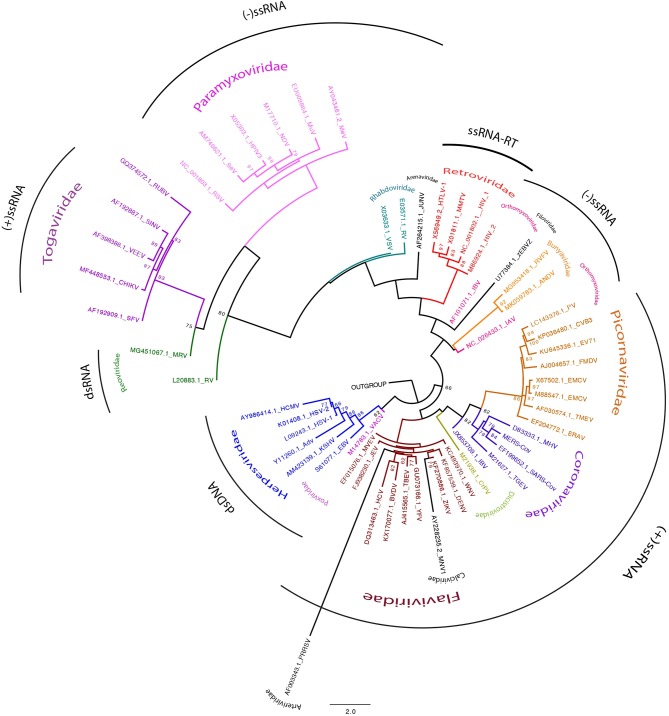

Viral infections are a major trigger of cellular stress and, thus, viruses have evolved diverse mechanisms aimed to modulate host RNAstasis with a direct impact in the assembly of different RNA granules while counteracting mRNA decay machineries in order to ensure viral replication (Poblete-Durán et al., 2016; Toro-Ascuy et al., 2016). In this review, we provide an update on the current knowledge of the different strategies used by several virus families to modulate the RNA granules assembly/disassembly, specifically SGs and PBs, in order to promote a successful viral infection (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Viral families tree. Phylogenetic tree showing 56 sequences representing all viral families described to modulate RNA granules assembly. The chosen sequences were “gene encoding to superficies structural protein.” The sequences were selected from NCBI databases (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/). Alignment were performed by MUSCLE (http://www.drive5.com/muscle/) (Edgar, 2004). Phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA6 (http://www.megasoftware.net) and IQ-TREE on the IQ-TREE web server (http://www.cibiv.at/software/iqtree/) (Trifinopoulos et al., 2016) by using the maximum-likelihood (ML) method. Robustness of tree topologies was assessed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using ML inference with the general time reversible (GTR)_G nucleotide substitution model. Viral families are showed in different colors. Genomes by clade are grouped by black arch.

Viral Families and Stress Granules

SGs are translationally silent membraneless organelles with a diameter between 0.1 and 4 μm. Canonical or bona fide SGs contain mRNA, RNA-binding proteins, and components of the 40S ribosomal subunit. Many proteins involved in SG assembly are RNA binding proteins that favor mRNA stability (TIA-1, TIAR, HuR), mRNA metabolism (G3BP-1, G3BP-2, DDX6, SMN, Staufen1, DHX36, Caprin1, ZBP1, HDAC6, ADAR), signaling proteins (mTOR, RACK1) and interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) products (PKR, ADAR1, RIG-I, RNase L, and OAS (reviewed in Poblete-Durán et al., 2016). Recently, Nunes et al. generated an open access electronic resource containing all SGs-recruited protein reported to date (available at https://msgp.pt/) (Nunes et al., 2019). Its assembly is typically a consequence of translation repression upon phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α by environmental stress such as heat shock, UV irradiation, oxidative stress, viral infection, and even upon treatment with several drugs (see Table 1). Most of these stresses are sensed by the eIF2α kinases PKR, which is activated by double-stranded RNA during viral infection (Williams, 2001); PERK, which is activated upon accumulation of misfolded protein in the ER and during hypoxia (Harding et al., 2000); HRI, which is activated by oxidative stress and heme deprivation (Han et al., 2001); and GCN2, which is activated by aminoacid deprivation and UV irradiation (Jiang and Wek, 2005). However, SGs can also be formed by inhibitors of translation that target other components of the translation machinery (Table 1) or by overexpression of SG-associated proteins such as TIA-1/TIAR or G3BP-1 (Kedersha et al., 1999; Tourrière et al., 2003). In addition to its role in mRNA triage, SGs have been described as signaling centers. Recruitment of signaling proteins to SGs allow the crosstalk between multiple stress cascades including translational control pathways, prevention of apoptosis and innate immune responses against viral infections (reviewed in Kedersha et al., 2011; Onomoto et al., 2014; Mahboubi and Stochaj, 2017).

Table 1.

List of drugs/stressors used to induce or disassemble SGs and PBs.

| Class | Drug/stressor | Effect | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pateamine-A | Induces SG assembly | Interacts with eIF4A disrupting the eIF4F complex | Bordeleau et al., 2005; Kedersha et al., 2006 |

|

| Hippuristanol | Induces SG assembly | Inhibits eIF4A RNA binding activity | Bordeleau et al., 2006; Mazroui et al., 2006 |

|

| Translation inhibitors | Cycloheximide | Disassembles both SGs and PBs | Inhibits eEF2-mediated translation elongation | Obrig et al., 1971; Mollet et al., 2008 |

| Selenite | Induces non-canonical SG assembly | Enhances 4EBP-1 binding to eIF4E, thus disrupting the eIF4F complex | Fujimura et al., 2012 | |

| Sorbitol | Induces SG assembly | Causes osmotic stress, which enhances 4EBP-1 binding to eIF4E, thus disrupting the eIF4F complex | Patel et al., 2002 | |

| Arsenite | Induces SG and PB assembly | Induces HRI-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation* | McEwen et al., 2005 | |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Induces SG assembly | Induces PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation | Oslowski and Urano, 2011; Dimasi et al., 2017 |

|

| Heat-Shock | Induces SG assembly and inhibits PBs | Induces HRI-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation | McEwen et al., 2005; Aulas et al., 2017 |

|

| eIF2α kinases Stressors |

Poly I:C | Induces SG assembly | Induces PKR-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation | Weissbach and Scadden, 2012 |

| Bortezomib and MG132 (proteosome inhibitors) | Induce SG assembly | Induce HRI(Bortezomib)- and GCN2(MG132)- mediated eIF2α phosphorylation | Mazroui et al., 2007; Fournier et al., 2010 |

|

| Thapsigargin | Induces SG assembly | Induces PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation | Kimball et al., 2002 | |

| eIF2α modulators | ISRIB | Inhibit SG assembly | Prevents eIF2B inhibition, maintaining translation initiation despite eIF2α phosphorylation | Sidrauski et al., 2015 |

| Salubrinal | Induces SG assembly | Blocks eIF2α dephosphorylation | Boyce et al., 2005 | |

| Others | 1,6-Hexanediol | Disassembles and induces PB and SG assembly | Disrupt weak hydrophobic interactions causing quick disassembly of granules that reappear after a few minutes** | Wheeler et al., 2016; Kroschwald et al., 2017 |

| Zn+2 | Stress- inducible second messenger | Induces reversible multimerization, phase separation and SG recruitment of TIA-1 | Rayman et al., 2018 |

Arsenite can also induce SG assembly independent of HRI. In Drosophila, which lacks HRI, induces the PEK eIF2a kinase (Farny et al., 2009). In addition, Sharma et al. demonstrated that arsenite can also induce phosphorylation of PKR and SG assembly in HeLa and BCBL-1 cells (Sharma et al., 2017).

It has been shown to also alter many other cellular structures (Wheeler et al., 2016).

Here, we summarize how viruses modulate SG accumulation in order to maintain viral protein synthesis and particles production.

Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) Viruses

Herpesviridae

All members of the Herpesviridae family that have been studied prevent the accumulation of SGs. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection upregulates and relocalizes to the cytoplasm the SG components TTP, TIAR, and TIA-1 but does not induce SG assembly (Esclatine et al., 2004). The virion host shutoff (vhs) protein, an mRNA endonuclease, has been shown to be essential in SGs blockade as vhs-deficient HSV-1 (Δvhs) infected cells do trigger SG assembly (Esclatine et al., 2004; Dauber et al., 2011, 2016). HSV vhs is thought to facilitate viral mRNA translation throughout the viral cycle by reducing host mRNAs and preventing viral mRNA overload (Dauber et al., 2016). Δvhs-induced SGs accumulation correlates with increased PKR activation (Sciortino et al., 2013; Dauber et al., 2016; Burgess and Mohr, 2018), but while a group observed higher eIF2α phosphorylation (Pasieka et al., 2008; Burgess and Mohr, 2018), others did not (Dauber et al., 2011, 2016). This phenotype could be in part due the reduced levels of the late-expressed dsRNA binding protein Us11, that has been shown to block PKR activation (Mulvey et al., 2003; Dauber et al., 2011). Burgess and Mohr showed that dsRNA accumulates and partially localizes to Δvhs-induced SGs (Burgess and Mohr, 2018). Furthermore, they show that SGs are not assembled neither PKR is phosphorylated in Δvhs-infected cells upon treatment with ISRIB (see Table 1) or in absence of G3BP-1 or TIA-1. Based on these observations, the authors suggest that Δvhs-enhanced PKR activation is a consequence of SG assembly due to dsRNA accumulation (Burgess and Mohr, 2018). Interestingly, other HSV proteins have also been involved in SGs regulation, although it is not clear whether they all act cooperatively, or during different stages of the viral cycle. HSV-1 ICP27 has been shown to prevent formation of arsenite-induced SGs by inhibiting PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation (Sharma et al., 2017). On the other hand, overexpression of HSV-1 ICP8 protein, a G3BP binding partner, blocks arsenite-induced SG assembly (Panas et al., 2015). Similar to HSV-1, SGs do not assemble during herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection and its blockade is mediated by the vhs protein (Finnen et al., 2012; Dauber et al., 2014). HSV-2 vhs protein has also been shown to shutoff protein synthesis by depleting mRNAs (Smith et al., 2000). Wild Type (WT) HSV-2 impairs arsenite-induced SGs despite increased eIF2α phosphorylation, but not pateamine (eIF2α-independent)-induced SGs, indicating that vhs can disrupt or modify SGs independently of eIF2α phosphorylation (Finnen et al., 2012). Further investigation revealed that (i) vhs localizes to SGs, (ii) vhs not only inhibits SG assembly but also disrupts pre-assembled SGs, and (iii) vhs endoribonuclease activity is required in SGs modulation (Finnen et al., 2016). Interestingly, TIA-1 was shown to egress before G3BP in the course of vhs-mediated SGs disassembly, which could be explained by the G3BP-enriched core SG structure (Jain et al., 2016; Niewidok et al., 2018). Based on these results, the authors proposed that HSV-2 vhs modify SGs by directly or indirectly degrading mRNA. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) inhibits the assembly of SGs but induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Isler et al., 2005a). Typically, this ER stress response leads to eIF2α phosphorylation via PERK activation, but HCMV limits eIF2α phosphorylation without diminishing PERK activation (Isler et al., 2005b). Marshall et al. showed that infection with HCMV lacking pTRS1 and pIRS1, dsRNA-binding proteins linked to PKR pathway inhibition, results in increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation and the reduction of viral protein synthesis (Marshall et al., 2009). Both proteins have identical amino-terminal regions and share 35% of similarity in their carboxy-terminal regions, suggesting that HCMV pTRS1 and pIRS1 have redundant roles in evading dsRNA-mediated antiviral response. Ziehr et al. demonstrated that lack of both proteins also results in PKR activation and SG assembly, and that expression of either pTRS1 or pIRS1 is necessary and sufficient to prevent PKR activation, eIF2α phosphorylation and SG assembly (Ziehr et al., 2016). Furthermore, pTRS1 PKR binding domain (PDB) was shown to be critical to accomplish those three phenotypes suggesting that the main mechanism of HCMV to inhibit SG assembly is through PKR antagonism. Strikingly, pTRS1 transfection interferes with arsenite-induced SG assembly in WT and PKR-depleted cells, but pTRS1-ΔPBD does not, suggesting that pTRS1 could also obstruct SG assembly promoted by other eIF2α kinases and that its PDB is crucial for it. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) does not lead to SG accumulation via the viral protein ORF57 and SOX which are able to restrict arsenite-induced SG assembly independently (Sharma et al., 2017). ORF57, the HSV-1 ICP27 homologous, inhibits PKR/eIF2α phosphorylation by directly interacting with PKR via its N-terminal dsRNA-binding domain, and with PACT via its two N-terminal RNA-binding motifs, thus obstructing PKR binding to both dsRNA and PACT. The mechanism and the spatiotemporal regulation of SG assembly by the viral shutoff exonuclease SOX is unclear, but it might be related to its intrinsic RNA endonuclease activity similarly to HSV-2 vhs (Glaunsinger and Ganem, 2004; Sharma et al., 2017). Expression of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) protein EB2, the counterpart of KSHV ORF57 and HSV-1 ICP27, does not abolish SG assembly, neither PKR/eIF2α phosphorylation, indicating that this specific ability to regulate SGs is not conserved along herpesviruses (Sharma et al., 2017). Further research is necessary to define the effect of EBV on SG assembly.

Poxviridae

Unlike herpes viruses, Vaccinia virus (VACV), a member of Poxviridae family, exploits SG components to favor viral protein production (reviewed in Liem and Liu, 2016). VACV redistributes proteins from the host translation machinery and SGs, such as eIF4E, eIF4G, G3BP, and Caprin1 into viral replication factories (RFs) assembled in the cytoplasm of the host cell (Katsafanas and Moss, 2004, 2007). Notably, TIA-1 is not recruited into these replication foci (Walsh et al., 2008). How VACV redistributes each of these components remain unclear, but evidences have shown that VACV ssDNA-binding protein I3 associates and recruits eIF4G to ssDNA formed within the RFs (Zaborowska et al., 2012). Furthermore, it was shown that G3BP-1 and Caprin1 associate with nascent VACV DNA by mass spectrometry (Senkevich et al., 2017). Despite the disruption of canonical SGs for its own benefit, infection with the replication-defective VACV lacking E3L leads to the accumulation of granule-like structures around the RFs, named antiviral granules (AVGs), that arrest viral translation (Simpson-Holley et al., 2010). AVGs contain proteins that are typically found in SGs such as TIA-1, eIF3b, G3BP-1, and USP10, but they are not affected by cycloheximide, a drug that induce the disassembly of bona fide SGs (Simpson-Holley et al., 2010). AVG assembly requires eIF2α phosphorylation via PKR activation (Simpson-Holley et al., 2010; Pham et al., 2016), process that is inhibited in presence of E3L (Chang et al., 1992). Furthermore, TIA-1 is an essential component of AVGs, as in its absence these antiviral granules are not formed even if PKR and eIF2α are phosphorylated (Simpson-Holley et al., 2010). Interestingly, WT VACV infection also induces AVGs assembly that repress viral protein synthesis but to negligible levels (Rozelle et al., 2014). Recently, another mutant VACV lacking C7L/K1L was shown to induce AVG assembly (Liu and McFadden, 2014). AVGs accumulation was abolished and abortive infection was rescued in ΔC7L/K1L in SAMD9-depleted cells, suggesting that C7L/K1L antagonize SAMD9 host protein antiviral function. Even though SAMD9 localize to both ΔE3L and ΔC7L/K1L VACV induced-AVGs, infectivity neither AVG assembly is blocked with ΔE3L VACV in SAMD9-depleted cells, suggesting a different mode of organization of the granules induced by both mutants (Liu and McFadden, 2014). ΔC7L/K1L-dependent AVGs assembly is independent of eIF2α phosphorylation, in contrast to ΔE3L AVG accumulation (Liu and McFadden, 2014). Viral mRNA was shown to colocalize with AVGs during ΔC7L/K1L VACV infection, thus limiting translation of viral proteins (Sivan et al., 2018), as well as dsRNA, TIA-1 and the viral protein E3L (Meng and Xiang, 2019). Despite of that, TIA-1 is not required for ΔC7L/K1L-mediated AVG assembly as it is on ΔE3L (Meng and Xiang, 2019). The role of each viral system, E3L and C7L/K1L, to prevent formation of AVGs in the context of viral infection remain to be studied.

Double-Stranded RNA (dsRNA) Viruses

Reoviridae

Rotavirus replication, the prototypical member of the Reoviridae family, also occurs in viral replication factories and upon infection, synthesis of cellular proteins is reduced while viral protein production is maintained. Accumulation of viral dsRNA in the cytoplasm causes a persistent PKR-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation, even when eIF2α phosphorylation is not required for viral replication (Montero et al., 2008; Rojas et al., 2010). Despite that, rotavirus infection does not induce SG assembly; instead it changes the cellular localization of SG components (Montero et al., 2008). TIA-1 is relocalized to the cytoplasm, eIF4E distributes more homogeneously in the cytoplasm, and PABP is translocated to the nucleus through the viral protein NSP3 (Montero et al., 2008). Recently, Dhillon et al. determined that rotavirus remodels SGs by excluding some of their proteins, such as G3BP-1, hnRNP A1, and ZBP1, and then recruits these atypical granules to viral replication factories (Dhillon and Rao, 2018; Dhillon et al., 2018). It will be of interest to understand how rotavirus selectively excludes these specific SG components. In contrast, uncoating of the mammalian orthoreovirus (MRV) during the early stage of infection leads to eIF2α phosphorylation by the action of at least two eIF2 kinases, suggesting that MRV infection is a complex process that induces different types of stresses to the cell (Qin et al., 2009). Phosphorylation of eIF2α triggers SG accumulation (Qin et al., 2009). MRV cores are then recruited into the assembled SGs, a step that depends on synthesis of viral mRNA. As the infection proceeds, assembled SGs are disrupted in order to allow efficient synthesis of viral proteins, despite the sustained levels of eIF2α phosphorylation (Qin et al., 2011). Like rotavirus, MRV replication occurs in viral replication factories that grow in the perinuclear region (Rhim et al., 1962). The non-structural μNS viral protein associates with σNS, σ2, μ2, and λ1 are recruited into viral replication factories. μNS viral protein has been shown to localize with SGs, although is unable to independently prevent SGs accumulation (Carroll et al., 2014). Interestingly, the SG components G3BP-1, Caprin1, USP10, TIAR, TIA-1, and eIF3b were found to localize to the outer peripheries of viral replication factories (Choudhury et al., 2017). σNS and μNS were shown to be responsible for their redistribution as well as for disruption of the SG assembly. In addition, in the absence of G3BP-1 the other recruited SGs-associated protein, except for eIF3b, do not localize to RFs. The recruitment mode is thought to be as follows: Caprin1, USP10, TIAR, and TIA-1 interact with G3BP-1 which binds to σNS via its RNA recognition (RRM) and an arginine/glycine-rich (RGG) motifs. Then, σNS partner with μNS for RF localization, carrying all the other proteins with it (Choudhury et al., 2017).

Positive-Sense Single Stranded RNA ((+) ssRNA) Viruses

Picornaviridae

Members of the Picornaviridae family also modulate SGs accumulation during replication. Poliovirus (PV) regulates SGs in a time-dependent manner; at early times the 2A proteinase induces assembly of SGs (Mazroui et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008) that are later disassembled by the 3C proteinase through G3BP-1 cleavage (White et al., 2007). Despite of bona fide SG disruption, atypical SGs (aSGs) that contain TIA-1 and viral RNA, but no eIF4G nor PABP, still accumulate later in the course of PV infection (Piotrowska et al., 2010; White and Lloyd, 2011). A similar temporal control of SG assembly is exhibited by Coxsakievirus B3 (CVB3) and Enterovirus 71 (EV71). CVB3 2A proteinase induces SG assembly as early as 3 h post infection (hpi) in an eIF2α phosphorylation-independent manner (Wu et al., 2014; Zhai et al., 2018). It has been described that they have an antiviral role, inhibiting the biosynthesis of CVB3 (Zhai et al., 2018). However, at 6 hpi CVB3 induces the assembly of granules that do not contain G3BP-1 or eIF4G, likely because of G3BP-1 cleavage (Fung et al., 2013; Zhai et al., 2018). In the case of EV71, canonical SGs are assembled early during infection dependent on the PKR-eIF2α pathway (Zhu et al., 2016), but are dispersed at late stages of infection (Yang et al., 2018b; Zhang et al., 2018). Yet, atypical SGs in which TIA-1, TIAR, Sam68, and viral RNA are persistently aggregated in an eIF2α independent and cycloheximide-resistant manner remain during infection. Yang et al. showed that EV71 2A protease expression is enough for atypical SGs induction through the cleavage of eIF4GI and bona fide SGs blockage by abolishing eF4GI-G3BP-1 interaction (Yang et al., 2018a,b). In contrast, Zhang et al. reported that EV71 3C protease alone is sufficient to inhibit canonical SGs accumulation during late stages of infection through G3BP-1 cleavage at amino acid Q326 (Zhang et al., 2018). Interestingly, cells infected with EV71-2AC110S (a cleavage-deficient 2A protease) do form canonical SGs in which viral RNA is aggregated, suggesting that EV71 blocks bona fide SGs but induce atypical SGs to facilitate viral translation by stalling only cellular mRNAs (Yang et al., 2018b; Zhang et al., 2018). Unlike already mentioned picornaviruses, encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) infection does not induce SG assembly at all, and cleavage of G3BP-1 is the mechanism for their disruption (Ng et al., 2013). On the other hand, the leader (L) protein of Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) and mengovirus (a strain of EMCV) inhibit SG assembly without cleaving G3BP-1 (Borghese and Michiels, 2011; Langereis et al., 2013). A mutant mengovirus, in which the Zn-finger domain of L is disrupted, induces antiviral G3BP-1 aggregations in which Caprin-1 and PKR are recruited, resulting in PKR activation and viral replication inhibition (Langereis et al., 2013; Reineke et al., 2015). Foot and Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV) does not induce SG assembly despite strongly shutoff cap-dependent translation and G3BP-1 dephosphorylation at Ser-149 (Ye et al., 2018; Visser et al., 2019), suggesting that FMDV infection regulates the cellular stress response. In fact, G3BP-1, eIF4G, eIF3, and eIF2α protein levels are downregulated and eIF4E-BP and PKR are dephosphorylated during FMDV infection (Ye et al., 2018). Ye et al. showed that G3BP-1 cleavage by 3C protease impairs SG assembly (Ye et al., 2018) while Visser et al. argued that L protease catalytic activity is responsible for the impairment of SG assembly in infected cells, without affecting PKR signaling (White et al., 2007). In addition, Ye et al. reported that the 3C-induced cleavage of G3BP-1 inhibits the NF-κB-dependent induction of antiviral immune responses (Ye et al., 2018). By using a reporter system, it has been shown that G3BP-1 negatively regulates viral translation by interacting with a structure located at domain 4 of the viral IRES (Galan et al., 2017). Furthermore, the G3BP-1 S149A substitution impairs the negative effect of G3BP-1 on IRES translation, suggesting that G3BP-1 is an antiviral protein whose activity depends on its phosphorylation (Ye et al., 2018). Instead, FMDV induces the nuclear-to-cytoplasm translocation of Sam68 via a proteolytic cleavage of its C-terminal domain mediated by 3C protease (Lawrence et al., 2012). Interestingly, Sam68 and TIA-1 colocalize in transient cytoplasmic granule-like structures in infected cells. Moreover, Sam68 interacts with FMDV IRES and Sam68 knockdown leads to a reduction in virus production, suggesting that Sam68 is a proviral factor (Lawrence et al., 2012; Rai et al., 2015). Similar to FMDV, Equine Rhinitis A virus (ERAV) infection also disrupts SG assembly via L-protease mediated cleavage of G3BP-1 and G3BP-2, suggesting that this is a conserved mechanism among aphtoviruses. However, despite G3BP-1 cleavage at multiple positions during FMDV and ERAV infections, the products differ in molecular weight, suggesting that they do not induce identical cleavages of G3BP-1 (Visser et al., 2019).

Togaviridae

Among viruses of Togaviridae family, Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is the only member know to block SG assembly. G3BP-1 is sequestered by nsP3 in cytoplasmic foci (Fros et al., 2012) while G3BP-2 colocalizes with nsP2/3 in complexes different from viral replication factories (Scholte et al., 2015). Recently, it has been shown that dsRNA foci, nsP3-like granules and nsP1-coated structures are in close proximity, suggesting that CHIKV not only sequesters G3BP-1/-2 proteins in order to impair SGs assembly, but also to support viral replication (Remenyi et al., 2018). CHIKV dsRNA was shown to be undetectable in G3BP-1/-2 double knock-out (dKO) cells, indicating that G3BPs play key roles in RNA replication and formation of viral replication complexes (Kim et al., 2016). In contrast, Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis virus (VEEV) replication is not affected by G3BP-1/-2 dKO (Kim et al., 2016), but the SG-associated proteins FXR1, FXR2, and FMR1 have been shown to be essential factors for VEEV replication and protein production. Interestingly, VEEV infected cells contain both large and small plasma membrane-bound FXR-nsP3 complexes containing viral genomic RNA, suggesting a role of FXRs in viral replication and protection of viral genomic RNA from degradation during transport to the plasma membrane (Kim et al., 2016). Semliki Forest Virus (SFV) induces SG assembly early during infection in an eIF2α phosphorylation-dependent manner (McInerney et al., 2005). Nevertheless, at late stages of infection nsP3 promotes SG disassembly by sequestering G3BP-1 to sites of viral replication, which correlates with an increase in viral RNA levels (McInerney et al., 2005; Panas et al., 2012). Consistently, infection with a non-G3BP-1 binding SFV promotes a persistent accumulation of SGs containing G3BP-1 and TIA-1, which correlates with an attenuation in viral infection (Panas et al., 2015). On the other hand, Sindbis virus (SINV)-derived vectors induce PKR activation and the subsequent assembly of SGs containing TIA-1, eIF4E, and eIF4G (Venticinque and Meruelo, 2010). Furthermore, viral nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4 colocalize with aggregates containing G3BP-1 (Frolova et al., 2006; Gorchakov et al., 2008; Cristea et al., 2010) while nsP3 also interacts with G3BP-2. In 2011, Mohankumar et al. revealed that SINV infection induces the phosphorylation of eIF2α which correlates with a strong shutoff of de novo protein synthesis and 4E-BP1 dephosphorylation. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that SINV replication does not require the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and that later during infection, SINV suppresses Akt/mTOR activation in HEK cells (Mohankumar et al., 2011). Similar to CHIKV, G3BP-1/-2 dKO significantly reduce SINV replication rates and plaque size. However, FXR1/2 and FMR1 triple knock-out only induces a delay in viral particles production (Kim et al., 2016). Finally, it has been suggested that G3BP-1 plays a potential role in the encapsidation of Rubella virus (RUBV) due to the colocalization of RUBV genomic RNA, the non-structural viral protein P150 and G3BP-1 aggregates (Matthews and Frey, 2012).

Flaviviridae

West Nile virus (WNV), a member of the Flaviviridae family, was the first virus described to block SG assembly. The 3′ stem loop in the (–) RNA, which is the site of initiation for nascent genome RNA synthesis, captures the SG components TIA-1 and TIAR, suggesting that they have a role in viral replication (Li et al., 2002). In addition, TIA-1 and TIAR colocalize with viral replication complexes containing dsRNA and NS3 viral protein in the perinuclear region (Emara and Brinton, 2007). Although WT WNV impedes SGs assembly, the chimeric WNV W956IC induces PKR-dependent SG assembly due to the high levels of viral RNA that are produced (Courtney et al., 2012). Remarkably, WNV inhibits arsenite, but not heat shock, or DTT-induced SG assembly. High levels of GSH (antioxidant) has been shown to counteract arsenite-induced SGs, as during WNV infection even low levels of PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation upregulate ATF4 and Nrf2, transcription factors that induce antioxidant gene expression (Basu et al., 2017). Similar to WNV, TIA-1, and TIAR colocalize with viral replication complexes containing dsRNA and NS3 in Dengue Virus type 2 (DENV-2) infected cells (Emara and Brinton, 2007). In addition, a quantitative mass spectrometry study revealed that DENV-2 RNA interacts with the SG components G3BP-1/2, Caprin1, and USP10 (Ward et al., 2011). It has been shown that DENV infection generates a non-coding subgenomic flaviviral RNA (sfRNA) that binds to G3BP-1/2 and Caprin1, impairing its ability to induce the translation of interferon Stimulated Genes (ISGs) mRNAs in response to DENV infection (Bidet et al., 2014). Recently, it has been described that Zika virus (ZIKV) infection blocks SG assembly (Amorim et al., 2017; Basu et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2017; Bonenfant et al., 2019) despite a strongly induced translational shutoff and activation of both PKR- and UPR-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α, suggesting that ZIKV impairs SG assembly downstream of eIF2α phosphorylation (Hou et al., 2017). In addition, ZIKV infection impairs arsenite-, poly I:C and hippuristanol, but not DTT-, Pateamine A- and Selenite-induced SG assembly (Amorim et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2017; Bonenfant et al., 2019) without affecting levels of SG-nucleating proteins (Amorim et al., 2017; Bonenfant et al., 2019). Hou et al. showed that expression of ZIKV NS3, NS4, NS2B-3 or capsid protein are sufficient to inhibit SG assembly (Hou et al., 2017). Interestingly, during ZIKV infection the host proteins YB-1 and Ataxin-2 are redistributed to the nucleus, while HuR and TIA-1 are redistributed to the cytoplasm of infected cells (Bonenfant et al., 2019). Moreover, TIAR is partially redistributed to sites of viral replication in the perinuclear zone, as seen on its colocalization with NS1 and viral RNA (Amorim et al., 2017). Furthermore, G3BP-1 and HuR are isolated with replication complexes, but only G3BP-1 interacts with viral dsRNA (Hou et al., 2017; Bonenfant et al., 2019). G3BP-1, Caprin-1, TIAR, Ataxin-2 and YB-1 knockdown negatively affects virus production, while HuR and TIA-1 knockdown resulted in an increase of viral titers (Hou et al., 2017; Bonenfant et al., 2019). Specifically, G3BP-1 knockdown also decreases genomic RNA and viral protein levels, while HuR knockdown increases genomic RNA and protein level (Bonenfant et al., 2019). Together, these data suggest a possible proviral role of the SG components G3BP-1, Caprin-1, TIAR, Ataxin-2, and YB-1 in ZIKV replication (Hou et al., 2017; Bonenfant et al., 2019). Similar to ZIKV, Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), Murray Valley Encephalitis Virus (MVEV) and Yellow Fever Virus (YFV) capsid-expressing cells showed a significantly impairment in hippuristanol-induced SG assembly (Hou et al., 2017). Specifically, it has been shown that JEV core protein blocks SG assembly through an interaction with Caprin-1, resulting in the recruitment of other SG components such as G3BP-1 and USP10 (Katoh et al., 2013). A JEV virus carrying a non Caprin-1-binding core protein is less pathogenic in mice and exhibits lower propagation in vitro than WT virus, suggesting that SGs blockade is crucial to facilitate viral replication (Katoh et al., 2013). Analogous to WNV and DENV, Tick-Borne Encephalitis virus (TBEV) sequesters TIA-1 and TIAR to viral replication factories (Albornoz et al., 2014). In particular, TIA-1 binds viral RNA and acts as a negative regulator of TBEV translation, suggesting that TIA-1 function is independent of SG assembly (Albornoz et al., 2014). In addition, TBEV infection induces eIF2α-dependent SG assembly containing the canonical SGs markers G3BP-1, eIF3, and eIF4B (Albornoz et al., 2014). On the other hand, Bovine Viral Diarrhea virus (BVDV) impairs the assembly of arsenite-induced SGs and despite viral N-terminal protease (Npro) interaction with several SG components (such as YB-1, IGFBP2, DDX3, ILF2, and DXH9), this is not the mechanism by which BVDV blocks SG assembly (Jefferson et al., 2014). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) relocalizes G3BP-1, PABP1, ATX2, DDX3, TIA-1, and TIAR to viral replication factories in lipid droplets (LDs) (Ariumi et al., 2011; Garaigorta et al., 2012). In particular, DDX3 activates IKKα during HCV infection to induce LDs biogenesis (Li et al., 2013). Importantly, Garaigorta et al. reported that G3BP-1, TIA-1, and TIAR are required for viral RNA and protein synthesis early during infection, while G3BP-1, DDX3, and TIA-1 play a role in viral particle assembly (Garaigorta et al., 2012; Pène et al., 2015; Valiente-Echeverría et al., 2015). In addition, they showed that HCV induces SG assembly in a PKR-dependent manner in order to impair the translation of antiviral ISGs (Garaigorta et al., 2012). Ruggieri et al. showed that HCV induces an oscillation between SG assembly and disassembly as a result of balance between dsRNA-dependent PKR activation with the subsequent phosphorylation of eIF2α and the antagonist effect of GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α (Ruggieri et al., 2012). This tight balance allows HCV to chronically infect cells without affecting cell survival (Ruggieri et al., 2012). In addition, two other SG components have been related to HCV replication: Staufen1 and YB-1. Staufen1 is involved in cellular mRNA transport, translation and decay, and negatively regulates the assembly of SGs (Thomas et al., 2009). Despite YB-1 being a general translational repressor, it regulates SG assembly by inducing G3BP-1 mRNA translation through its interaction with the 5′UTR of the mRNA (Somasekharan et al., 2015). In 2016, Dixit et al. showed that Staufen1 interacts directly with PKR and NS5B, and that this interaction is required to inhibit PKR activation during HCV infection to allow viral RNA translation. In addition, the interaction of Staufen1 with NS5B suggests a role of Staufen1 in HCV replication, which is in accordance with a strong reduction in viral RNA and NS5A and NS5B protein levels in cells transfected with and Staufen1-siRNA (Dixit et al., 2016). Moreover, Wang et al. demonstrated that YB-1 knockdown reduces the phosphorylation status of NS5A, which is crucial for the NS5A-mediated regulation of RNA replication and virus assembly (Wang et al., 2015). Also, YB-1 interacts with NS5A in an YB-1 phosphorylation-dependent manner and this interaction is crucial for NS5A protein stability during HCV infection. Interestingly, YB-1 is phosphorylated by Akt at serine 102 and is known that HCV infection and NS5A expression activate the PI3K/Akt signaling (Wang et al., 2015). Together, these observations could explain the oscillation of SG assembly/disassembly detected in HCV-infected cells (Ruggieri et al., 2012) and how SG assembly and SG components are necessary for HCV RNA replication, assembly and egress (Ariumi et al., 2011; Garaigorta et al., 2012; Pager et al., 2013).

Dicistroviridae

Cricket Paralysis Virus (CrPV) is the only described member of Dicistroviridae family that regulates SG assembly. CrPV 1A protein impairs the assembly of arsenite-, Pateamine A-, and heat shock-induced SGs containing Rox8 and Rin, Drosophila homologs of TIA-1 and G3BP-1 respectively, demonstrating that there is a conserved mechanism in insect and human cells (Khong and Jan, 2011; Khong et al., 2016). In addition, CrPV-induced inhibition of SG assembly is not due to a cleavage of Rox8 or Rin despite 3C proteinase sequestration in SGs (Khong and Jan, 2011).

Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae

Transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), a member of the Coronaviridae family, induces SG assembly later during infection (Sola et al., 2011). The SGs component PTB binds to TGEV genomic and subgenomic RNA and colocalize with TGEV-induced aggregates containing TIA-1 and TIAR (Sola et al., 2011). In addition, Xue et al. described that PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation during TGEV infection is detrimental for viral replication due to the global translational repression induced by activation of the IFN pathway (Xue et al., 2018). On the other hand, Mouse Hepatitis Coronavirus (MHV) induces the aggregation of TIAR early during infection in an eIF2α phosphorylation-dependent manner and, in contrast to TGEV, translational shutoff induced by MHV enhanced viral replication (Raaben et al., 2007). Moreover, MHV infection does not induce the expression of factors necessary to dephosphorylate eIF2α such as CHOP and GADD34 (Bechill et al., 2008). MHV N protein strongly impairs the IFN-induced PKR signaling activation, suggesting a viral regulation of the cellular antiviral response (Ye et al., 2007). Recently, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was shown to impair SG assembly even when viral dsRNA alone activates PKR-mediated SG assembly, suggesting that the virus protects its viral dsRNA from PKR (Rabouw et al., 2016; Nakagawa et al., 2018). Rabouw et al. showed that viral protein p4a antagonizes PKR activity through its dsRNA-binding motif and inhibits partially arsenite-dependent SG assembly, suggesting that p4a suppresses PKR but no other pathways of the cellular stress response (Rabouw et al., 2016). In addition, MERS-CoV replication is significantly impaired in cells depleted of TIA-1 or G3BP-1/-2, suggesting a potential proviral role of these SG components (Nakagawa et al., 2018). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) induces a strong inhibition of host protein synthesis mediated by the nsp1 viral protein, which interacts with the 40S ribosomal subunit, impairing 80S formation (Narayanan et al., 2008; Kamitani et al., 2009). In addition, SARS-CoV infection induces PKR-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation, while GCN2 protein levels decreased in infected cells (Krahling et al., 2008). Finally, Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus (IBV) induces PERK and eIF2α phosphorylation at early times post infection, while induces GADD34 expression and the subsequent eIF2α dephosphorylation at late stages of the course of infection in order to maintain viral protein synthesis (Wang X. et al., 2009; Liao et al., 2013). Interestingly, IfnB mRNA, but not IFN protein was detected in the supernatant of IBV infected cells, probably due to a 5b-mediated inhibition of general protein synthesis (Kint et al., 2016). However, although it has been described that SARS-CoV and IBV regulate eIF2α phosphorylation in infected cells, it has not been evaluated whether it result in SG assembly or blockade. In contrast, it is known that Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV), a member of the Arteriviridae family, induces canonical SG assembly mediated by PERK and eIF2α phosphorylation in infected cells (Zhou et al., 2017).

Caliciviridae

Members of the Caliciviridae family block SG assembly by targeting G3BP-1. Although Feline Calicivirus (FCV) infection results in eIF2α phosphorylation, viral 3C-like NS6 proteinase cleaves G3BP-1, thus impeding SG assembly in infected cells (Humoud et al., 2016). Similarly, Murine Norovirus 1 (MNV1) induces a shutoff of global translation by triggering the phosphorylation of eIF4E and eIF2α in a PKR-dependent manner, without inducing SG assembly (Royall et al., 2015; Brocard et al., 2018; Fritzlar et al., 2019). Interestingly, MNV1 infected cells showed a redistribution of G3BP-1 to sites of viral replication closely to the nucleus, colocalizing with NS5 (Fritzlar et al., 2019) or NS3 viral protein (Brocard et al., 2018). Together, these observations showed that MNV impairs SG assembly by sequestering G3BP-1, thus, uncoupling the cellular stress response (Brocard et al., 2018; Fritzlar et al., 2019). Although Humoud et al. showed that MNV does not impair arsenite-induced SGs, recently Fritzlar et al. demonstrated the opposite (Humoud et al., 2016; Fritzlar et al., 2019).

Negative-Sense Single Stranded ((–) ssRNA) Viruses

Orthomyxoviridae

Influenza A virus (IAV) and Influenza B virus (IBV), members of the Orthomyxoviridae family, block SG assembly during infection. IAV disrupts SGs accumulation by expressing three different proteins: the host-shutoff protein polymerase-acidic protein-X (PA-X), the nucleoprotein (NP), and the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) (Khaperskyy et al., 2014). PA-X inhibits SG assembly in an eIF2α-independent manner, and requires its endoribonuclease activity for this function (Khaperskyy et al., 2014). It causes nuclear relocalization of PABP1, a phenotype that has been observed with other viral host-shutoff proteins (Khaperskyy et al., 2014). In addition, it depletes poly(A) RNAs from the cytoplasm but promotes its accumulation in the nuclei (Khaperskyy et al., 2014). A recent publication demonstrates that PA-X selectivity degrades host RNAs by selecting transcripts that have undergone splicing, and that can interact with cellular proteins involved in RNA splicing (Gaucherand et al., 2019). NP can block arsenite-induced SGs accumulation in an eIF2α-independent manner, but its effect depends on its expression levels (Khaperskyy et al., 2014). In contrast, NS-1-mediated inhibition of SG assembly depends on the PKR pathway; NS-1 binding to dsRNA inhibits PKR autophosphorylation and subsequent eIF2α phosphorylation (Khaperskyy et al., 2011). Interestingly, the SGs-associated proteins RAP55, DDX3, and NF90 have been shown to interact with both NP and NS-1, which could represent the cell‘s attempt to inhibit IAV infection or most the virus hijacks these host proteins to block SG assembly (Wang P. et al., 2009; Mok et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016; Raman et al., 2016). NP and DDX3 are recruited to SGs during ΔNS1 IAV infection (Onomoto et al., 2012; Raman et al., 2016), but in presence of NS1 NP localizes to PBs instead, suggesting that NS1 is essential for NP escape from SGs (Mok et al., 2012). Normally NF90 leads to SG accumulation by directly binding and activating PKR, but in presence of IAV NS1, NF90 binds preferentially to it rather than PKR, suggesting that NS1 also suppress PKR activation by blocking NF90-PKR interaction (Wen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016). Similarly, IBV requires NS1 in order to restrict SG assembly (Núñez et al., 2018). The vRNA sensor retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I) is recruited to SGs and induces IFN response during ΔNS1 IAV and IBV infections (Onomoto et al., 2012; Núñez et al., 2018). Furthermore, RIG-I was shown to associate with DDX6, which upon binding to vRNA stimulated RIG-I IFN induction (Núñez et al., 2018).

Arenaviridae

Infection with Junin virus (JUNV), a member of the Arenaviridae family, inhibits SG assembly in mock and arsenite-treated cells by impairing eIF2α phosphorylation. To do so, the presence of either NP or glycoprotein precursor (GPC) is required, as they both block SGs accumulation when expressed individually in cells (Linero et al., 2011). Recently, JUNV NP was found to interact with PKR, G3BP-1, eIF2α, hnRNP A1, and hnRNP K (King et al., 2017), as well as with DDX3 (Loureiro et al., 2018). Upon infection, PKR expression increases but is targeted to viral replication factories (RFs) together with NP, G3BP-1, dsRNA, PKR, phosphorylated PKR, RIG-I, and MDA-5 (King et al., 2017; Mateer et al., 2018). Despite the high levels of PKR activation, JUNV fails to induce eIF2α phosphorylation, maybe due its sequestration to the RFs via NP (King et al., 2017). Lassa virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) NPs also interact with G3BP-1, eIF2α, and DDX3 (King et al., 2017; Loureiro et al., 2018). PKR interaction with LCMV NP occurs but weakly than with JUNV NP, which is reflected in the lack of PKR upregulation and colocalization with NP, and the increased eIF2α phosphorylation level compared to JUNV infection (King et al., 2017).

Rhabdoviridae

The vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), member of the Rhabdoviridae family, promotes eIF2α phosphorylation and downregulates the synthesis of cellular proteins while maintaining viral production (Dinh et al., 2012). Under these conditions, it forms aSGs that contain PCBP2, TIA-1 and TIAR, but no eIF3 or eIF4A. VSV RNA, phosphoprotein (P) and NP are also part of these atypical SG-like structures, whose induction requires ongoing viral protein synthesis and viral replication (Dinh et al., 2012). Interestingly, assembly of aSGs and bona fide arsenite-induced SGs can occur simultaneously, revealing that VSV infection suppresses the accumulation of bona fide antiviral SGs and utilize SGs-associated components for its own benefit (Dinh et al., 2012). In contrast, Rabies virus (RABV) effectively replicate in cells that assemble SGs upon infection (Nikolic et al., 2016). The observed SGs contain G3BP-1, TIA-1 and PABP, and their accumulation is dependent on PKR-induced eIF2α phosphorylation, suggesting that they are canonical SGs. Notably, PKR and TIA-1 depletion enhances viral replication, revealing that they have an antiviral effect but that is not strong enough to completely stop RABV infection. RABV-induced SGs locate adjacent to viral RFs. Interestingly, viral mRNA but no viral genomic RNA is transported from RFs to SGs, suggesting that RABV may be using SGs to modulate viral transcription and replication (Nikolic et al., 2016).

Paramyxoviridae

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), member of the Paramyxoviridae family, replicate in viral replication factories (RFs) which have been observed to interact with SGs. However, seemingly contradictory findings have been reported for RSV. Lindquist et al. showed that RSV replication induces SG assembly in ~10–25% of the infected cells, and that they enhance RFs formation and viral replication (Lindquist et al., 2010, 2011). SGs accumulation requires PKR activation, which induces eIF2α phosphorylation, however PKR depletion did not affect RSV replication (Lindquist et al., 2011). Contrastingly, Groskreutz et al. reported that RSV infection activates PKR but does not trigger eIF2α phosphorylation due to PKR sequestration by the RSV NP (Groskreutz et al., 2010). Two other groups reported that RSV induce SG aggregation in ~1% (Hanley et al., 2010) and ~5% (Fricke et al., 2012) of the infected cells, revealing that, in general, RSV inhibits their assembly. Sequestration to RFs of the O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT), a factor involved in SGs regulation, and the presence of the 5′ extragenic trailer sequence of the RSV genome have been associated with SGs suppression (Hanley et al., 2010; Fricke et al., 2012). Measles virus (MeV) infection does not induce SG assembly due to the PKR inhibitory effect of the viral accessory protein C (Okonski and Samuel, 2012). To block PKR autophosphorylation, MeV C protein requires the presence of the dsRNA binding protein and the SGs-component ADAR1, as WT MeV infection induce PKR activation and SGs accumulation in ADAR1 depleted cells (Toth et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; Okonski and Samuel, 2012). Furthermore, infection with ΔC-MeV produces large amounts of dsRNA that activate PKR and induce SGs assembly, suggesting that the C protein may utilize ADAR1 to downregulate the viral dsRNA produced during replication (Pfaller et al., 2013). Both ADAR1 and C protein colocalize with SGs (Okonski and Samuel, 2012). Similar to RSV, Sendai virus (SeV) induces SGs accumulation in just a fraction of the cells (5–15%) and the 5′ trailer region of its sequence has been implicated in SG assembly prevention via interaction with TIAR (Iseni et al., 2002). Like MeV, the SeV C protein is required to impair SG assembly in control and arsenite-treated cells, although C protein expression alone is not able to do so (Yoshida et al., 2015). ΔC-SeV assembled SGs contain RIG-I and unusual viral RNA species. Recently, the effect on SG assembly of three more paramyxoviruses have been studied. Newcastle disease virus (NDV) infection trigger the canonical SGs assembly to arrest host mRNAs and boost viral replication (Oh et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017). SG assembly is dependent on PKR/eIF2α phosphorylation and its suppression (by depleting TIA-1 or TIAR proteins) reduces viral protein synthesis but increases cellular protein synthesis (Sun et al., 2017). Accordingly, cellular mRNAs have been shown to be predominately recruited to SGs compared to viral mRNAs (Sun et al., 2017). Strikingly, RIG-I is also recruited to the assembled SGs, which induces IFN production as an antiviral response (Oh et al., 2016). Likewise, Mumps virus (MuV) infection promotes SG assembly dependent on PKR activation despite weak eIF2α phosphorylation (Hashimoto et al., 2016). PKR, G3BP-1 and TIA-1 depletion reduces MeV-SGs and increased IFN response, but did not alter viral titers, suggesting that MuV replication occurs independently of the presence or absence of SGs. Conversely, Human Parainfluenza Virus Type 3 (HPIV3) infection leads to assembly of SGs that seem to have a poor antiviral role, as it is able to replicate in presence of SGs although viral protein expression and particle production is improved when SG assembly is constrained by knockdown of PKR, G3BP-1 or expression of a non-phosphorylatable eIF2α (Hu et al., 2018). SG assembly is due eIF2α PKR-dependent phosphorylation triggered by viral mRNAs, which can be shielded, and therefore block SGs assembly, by HPIV3 RFs (Hu et al., 2018).

Bunyaviridae

Since our last review (Poblete-Durán et al., 2016), no new reports have been published on how members of the Bunyaviridae family modulate SG assembly. Briefly, Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) infection inhibit SG assembly despite attenuation of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway which leads to the arrest of cap-dependent translation (Hopkins et al., 2015). It has been shown that non-structural protein from the S segment of Orthobunyaviruses, Hantaviruses and Phleboviruses (Kohl et al., 2003; Jaaskelainen et al., 2009), as well as glycoprotein Gn and the capsid N protein from Hantaviruses (Alff et al., 2006; Cimica et al., 2014; Matthys et al., 2014), inhibit IFN response.

Interestingly, the Andes Hantavirus (ANDV) N protein inhibits PKR dimerization, but this lack of activation does not stop protein translation (Wang and Mir, 2014). In contrast, RVFV infection promotes a protein translation shutoff due to PKR degradation by NSs protein (Habjan et al., 2009; Ikegami et al., 2009).

Filoviridae

Ebola virus (EBOV), member of the Filoviridae family, inhibits the assembly of SGs and instead sequesters the SGs-associated proteins eIF4G, eIF3, PABP, and G3BP-1, but no TIA-1 into granules within the viral replication factories (Nelson et al., 2016). These inclusion-bodies (IB) granules do not require eIF2α phosphorylation, do not disassemble with cycloheximide, and do not block translation. Furthermore, arsenite, heat and hippuristanol can still induce bona fide SGs accumulation, suggesting that sequestration of SGs proteins in IB granules may be released upon stress. EBOV VP35 was found to be the protein that prevents the bona fide SG assembly late in infection, and its C-terminal domain is critical for this function (Le Sage et al., 2016). VP35-CTD contains an inhibition of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) domain that is responsible for blocking PKR activation during EBOV infection (Schumann et al., 2009). However, when expressed in sufficient high levels, VP35 can block arsenite-induced SGs without reducing the levels of eIF2α phosphorylation, suggesting that VP35 suppress SG assembly by using an alternative way to PKR (Le Sage et al., 2016). VP35 can interact with several SG-associated proteins such as G3BP-1, eIF3, and eEF2 and it is targeted to viral replication factories, suggesting that it may be blocking SG assembly by relocating SG constituents (Le Sage et al., 2016; Nelson et al., 2016).

Single Strand RNA Retroviruses (ssRNA-RTs)

Retroviridae

Viruses belonging the Retroviridae family integrate its retrotranscribed (+)ssRNA into the host chromosomal DNA (Fields et al., 2013). The Human T-Lymphotropic Virus 1 (HTLV1) Tax protein blocks SG assembly by interacting with the SG components histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) (Legros et al., 2011) and USP10 (Takahashi et al., 2013). Similarly, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type I (HIV-1) also blocks SG assembly despite eIF2α phosphorylation, through an interaction between Gag and the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) (Valiente-Echeverría et al., 2014; Poblete-Durán et al., 2016). HIV-1 Gag also disassembles pre-formed arsenite-induced SGs by interacting with G3BP-1 (Valiente-Echeverría et al., 2014) and selenite-induced atypical SGs by interacting with eIF4E (Cinti et al., 2016; Poblete-Durán et al., 2016). Notably, G3BP-1 was shown to act as a restriction factor that inhibits viral replication by interacting with HIV-1 genomic RNA (gRNA) in macrophages (Cobos Jiménez et al., 2015). Recently, Rao et al. described a novel HIV-1 NC-induced SGs containing G3BP-1, TIAR, eIF3, PABP, and poly(A) mRNAs that are no longer disassembled by Gag or CA (Rao et al., 2017). HIV-1 NC expression significantly increased eIF2α phosphorylation, inhibiting protein synthesis and reducing viral particle production. In addition, NC was shown to interact with G3BP-1, TIAR, and Staufen1 even in absence of RNA. The inability of NC to assembly SGs in G3BP-1 depleted cells suggest that their interaction is required to promote NC-induced SG accumulation (Rao et al., 2017). The authors also showed that Staufen1 counteracts NC-induced PKR-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation and translational shutoff (Rao et al., 2017). Interestingly, while HIV-1 impairs SGs assembly, the virus favors the assembly of Staufen1-containing HIV-1 dependent ribonucleoproteins (Abrahamyan et al., 2010). Indeed, it has been reported that HIV-1 is unable to dissociate or block arsenite-induced SG assembly in Staufen1 knock-out cells, suggesting that the recruitment of Staufen1 is crucial for HIV-1 SGs blockade. In addition, in absence of Staufen1 the HIV-1 genomic RNA colocalizes with TIAR in arsenite-induced SGs, which correlates with a significant reduction of Gag protein levels possibly due to the robust eIF2α phosphorylation induced by HIV-1 infection (Rao et al., 2019b). Besides these data, Soto-Rifo et al. showed that DDX3, eIF4GI, and PABPC1 form a pre-translation initiation complex with the HIV-1 genomic RNA to promote viral translation (Soto-Rifo et al., 2014; Poblete-Durán et al., 2016). In contrast to HIV-1, HIV-2 infection does not block SG assembly and the viral genomic RNA recruits TIAR in a different type of RNA granules where it is suggested that the transition from translation to packaging occurs (Soto-Rifo et al., 2014). On another hand, Bann et al. showed that Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV) Gag interacts and colocalizes with the SGs component YB-1 in small cytoplasmic foci in an RNA-dependent manner. Interestingly, these foci also contain viral RNA and are insensitive to cycloheximide treatment. It is suggested that YB-1 plays key roles in MMTV as YB-1 knockdown results in a significant reduction in viral particle production (Bann et al., 2014).

In summary, information about virus-host interaction mediated by membraneless organelles in order to ensure viral replication can be found summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Virus families that modulate SGs.

| Genome | Virus family | Virus | SGs induction | SGs blockade | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dsDNA | Herpesviridae | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 (HSV-1) |

No | Yes | vhs is required for inhibition of SG assembly dependent on PKR | Esclatine et al., 2004; Dauber et al., 2011, 2016; Sciortino et al., 2013 |

| vhs-dependent SGs inhibition is independent on eIF2α phosphorylation | Dauber et al., 2011, 2016 | |||||

| vhs-dependent SG inhibition is dependent on eIF2α phosphorylation, dsRNA partially localizes to SGs, and SG assembly activates PKR | Burgess and Mohr, 2018 | |||||

| ICP27 inhibits phosphorylation of PKR/eIF2α and blocks SG assembly | Sharma et al., 2017 | |||||

| ICP8 interacts with G3BP and blocks SG assembly | Panas et al., 2015 | |||||

| Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) |

No | Yes | HSV-2 inhibits SG assembly independent on eIF2α phosphorylation | Finnen et al., 2012 | ||

| vhs is required for disruption of canonical and arsenite-induced SGs | Finnen et al., 2012 | |||||

| vhs inhibit SG assembly and disrupt pre-assembled SGs, and its endoribonuclease activity is required | Finnen et al., 2016 | |||||

| Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) | No | Yes | HCMV inhibits eIF2α phosphorylation | Isler et al., 2005b | ||

| HCMV inhibits SG assembly | Isler et al., 2005a | |||||

| Lack of viral proteins pIRS1 and pTRS1 increase levels of eIF2α phosphorylation | Marshall et al., 2009 | |||||

| pTRS1 or pIRS1 inhibits SG assembly dependent on PKR. Transfected pTRS1 also prevent SG assembly independent on PKR | Ziehr et al., 2016 | |||||

| Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) | No | Yes | ORF57 interacts with PKR inhibiting its binding to dsRNA and its activation, which impairs eIF2α phosphorylation and SG assembly | Sharma et al., 2017 | ||

| SOX inhibits arsenite-induced SG assembly | Sharma et al., 2017 | |||||

| Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) | ND | ND | EB2 overexpression does not abolish SG assembly neither PKR/eIF2α phosphorylation | Sharma et al., 2017 | ||

| Poxviridae | Vaccinia virus (VACV) | Yes (AVGs) |

Yes | G3BP-1, Caprin 1, eIF4G, eIF4E, PABP are sequestered into RFs | Katsafanas and Moss, 2004 | |

| VACV lacking E3L induce AVGs which require TIA-1 expression | Simpson-Holley et al., 2010 | |||||

| ΔE3L induced AVGs requires eIF2α phosphorylation | Pham et al., 2016 | |||||

| WT VACV spontaneously form AVGs but to negligible levels | Rozelle et al., 2014 | |||||

| ΔC7L/K1L VACV induce AVGs assembly dependent on SAMD9 host protein and independent of eIF2α phosphorylation | Liu and McFadden, 2014 | |||||

| Viral mRNA is recruited to ΔC7L/K1L VACV induced AVGs | Sivan et al., 2018 | |||||

| TIA-1 is not required for ΔC7L/K1L-mediated AVG assembly | Meng and Xiang, 2019 | |||||

| dsRNA | Reoviridae | Rotavirus | No | Yes | Rotavirus inhibits SG assembly independent on eIF2α phosphorylation, but changes the localization of TIA-1, eIF4E, and PABP | Montero et al., 2008 |

| Relocalizes ADAR1, Caprin1, CPEB, eIF2α, 4EBP1, PKR, and Staufen1 to RFs, and selectively excludes G3BP-1 and ZBP1 | Dhillon and Rao, 2018; Dhillon et al., 2018 | |||||

| Mammalian orthoreovirus (MRV) | Yes (canonical) | Yes | SGs are formed during the early stage of infection but disassembled in later stages independent on eIF2α phosphorylation | Qin et al., 2009, 2011 | ||

| μNS is recruited to SGs | Carroll et al., 2014 | |||||

| MRV relocalizes G3BP-1, Caprin1, USP10, TIAR, TIA-1, eIF3b to RFs via G3BP1-oNS-uNS interaction | Núñez et al., 2018 | |||||

| (+)ssRNA | Picornaviridae | Poliovirus (PV) | Yes (canonical and atypical) |

Yes | 2A-protease mediated SGs assembly | Mazroui et al., 2006 |

| 3C protease-mediated G3BP-1 cleavage | White et al., 2007 | |||||

| Induces aggregates containing TIA-1 and viral RNA | Piotrowska et al., 2010 | |||||

| Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) |

No | Yes | Cleavage of G3BP-1 | Ng et al., 2013 | ||

| Coxsakievirus B3 CVB3 | Yes (canonical and atypical) |

Yes | Cleavage of G3BP-1 | Fung et al., 2013 | ||

| 2A protease-mediated SGs assembly | Zhai et al., 2018 | |||||

| 2A protease-mediated eIF4G cleavage | Wu et al., 2014 | |||||

| Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) | No | Yes | Inhibition of SG assembly mediated by Leader protein (L) | Borghese and Michiels, 2011 | ||

| Enterovirus 71 (EV71) | Yes (canonical and atypical) |

Yes | 2A protease-mediated inhibition of SGs | Zhu et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018b | ||

| PKR-eIF2α phosphorylation- dependent SG assembly mediated by 2A protease | Zhang et al., 2016, 2018; Zhu et al., 2016 | |||||

| Cleavage of eIF4GI mediated by 2A protease, abolishing eIF4GI and G3BP-1 interaction | (Yang et al., 2018a,b) | |||||

| Cleavage of G3BP-1 mediated by 3C protease | Zhang et al., 2018 | |||||

| Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV) | No | Yes | Shuts-off host cap-dependent translation mediated by eIF2α downregulation and PKR dephosphorylation | Ye et al., 2018 | ||

| Cleavage of G3BP-1 and Sam68 mediated by 3C protease | Lawrence et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2018 | |||||

| Cleavage of G3BP-1 mediated by Leader protease | Visser et al., 2019 | |||||

| Equine Rhinitis A virus (ERAV) | ND | Yes | Cleavage of G3BP-1 and G3BP-2 by Leader protease | Visser et al., 2019 | ||

| Mengovirus, a strain of EMCV | No | Yes | Leader protein (L) inhibits SG assembly | Langereis et al., 2013; Reineke et al., 2015 | ||

| Togaviridae | Semliki Forest Virus (SFV) | Yes (canonical) |

Yes | Induces eIF2α phosphorylation | McInerney et al., 2005 | |

| nsP3 sequesters G3BP-1 and G3BP-2 into RFs | Panas et al., 2012 | |||||

| G3BP-1 binding by nsP3 is necessary for SGs blockage | Panas et al., 2015 | |||||

| Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) | No | Yes | Nsp3 sequesters G3BP-1 to RFs | Fros et al., 2012; Remenyi et al., 2018 | ||

| G3BP-2 colocalizes with nsP2/nsP3 complexes | Scholte et al., 2015 | |||||

| Rubella virus (RUBV) | Yes | No | Accumulation of G3BP-1 | Matthews and Frey, 2012 | ||

| Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) | ND | ND | nsP3 interacts with FXRs to facilitate viral RFs formation | Kim et al., 2016 | ||

| Sindbis virus (SINV) | Yes (canonical) |

Yes | Nsp4 interacts with G3BP-1 | Cristea et al., 2010 | ||

| Induces PKR-dependent SGs assembly | Venticinque and Meruelo, 2010 | |||||

| Nsp3 protein interacts with G3BP-1 and G3BP-2 | Kim et al., 2016 | |||||

| Flaviviridae | West Nile Virus (WNV) | No | Yes | Viral RNA captures TIA-1 and TIAR | Li et al., 2002 | |

| Increased GSH levels inhibit arsenite-induced SGs | Basu et al., 2017 | |||||

| Dengue Virus (DENV) | No | Yes | Viral RNA colocalizes with TIA-1 and TIAR | Emara and Brinton, 2007 | ||

| 3′UTR interacts with G3BP-1, G3BP-2, Caprin 1 and USP1 | Ward et al., 2011 | |||||

| Zika Virus (ZIKV) | No | Yes | ZIKV impairs SG assembly downstream of eIF2α phosphorylation | Hou et al., 2017 | ||

| Expression of ZIKV capsid, NS3, NS2B-3, or NS4A protein inhibits SG assembly. Capsid protein interacts with G3BP-1 and Caprin-1 | Hou et al., 2017 | |||||

| Relocalizes Ataxin-2, HuR and YB-1. G3BP-1 and TIAR localize at viral RFs | Bonenfant et al., 2019 | |||||

| Yellow Fever Virus (YFV) | ND | Yes | Ectopically expressed capsid protein blocks hippuristanol-induced SGs | Hou et al., 2017 | ||

| Murray Valley Encephalitis Virus (MVEV) | ND | Yes | Ectopically expressed capsid protein blocks hippuristanol-induced SGs | Hou et al., 2017 | ||

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) |

Yes (canonical) |

No | Induces eIF2α phosphorylation | Albornoz et al., 2014 | ||

| Sequesters TIA-1 and TIAR to RFs | Albornoz et al., 2014 | |||||

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) |

No | Yes | Core protein interacts with Caprin 1 | Katoh et al., 2013 | ||

| Ectopically expressed capsid protein blocks hippuristanol-induced SGs | Hou et al., 2017 | |||||

| Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) |

No | Yes | Impairs arsenite-induced SGs assembly | Jefferson et al., 2014 | ||

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | Yes | Yes | G3BP-1, Ataxin-2, PABP1, DDX3, TIA-1, and TIAR are recruited to lipid droplets | Ariumi et al., 2011; Garaigorta et al., 2012 | ||

| Induces SGs dependent on PKR and IFN | Garaigorta et al., 2012 | |||||

| GADD34-mediated SGs disassembly | Ruggieri et al., 2012 | |||||

| DDX3 binds viral 3'UTR | Li et al., 2013 | |||||

| DDX3 and G3BP-1 localize with HCV core protein | Pène et al., 2015 | |||||

| Staufen 1 inhibits PKR activation | Dixit et al., 2016 | |||||

| Dicistroviridae | Cricket paralysis virus (CrPV) | No | Yes | 3C protease is sequestered to SGs | Khong and Jan, 2011 | |

| CrPV-1A protein disrupts Pateamine A, arsenite and heat shock-induced SGs assembly | Khong et al., 2016 | |||||

| Coronaviridae | Mouse hepatitis coronavirus (MHV) |

Yes | No | Induces eIF2α phosphorylation | Raaben et al., 2007; Bechill et al., 2008 | |

| N protein impairs PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation during IFN treatment | Ye et al., 2007 | |||||

| Transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) | Yes | No | PTB localization in SGs correlates with an increase in viral replication | Sola et al., 2011 | ||

| Induces PERK-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation | Xue et al., 2018 | |||||

| Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) | No | Yes | 4a protein inhibits PKR-dependent SG assembly by binding and sequestering dsRNAs from PKR | Rabouw et al., 2016; Nakagawa et al., 2018 | ||

| Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) |

ND | ND | Nsp1 induces translational shutoff by impairing 80S formation | Narayanan et al., 2008; Kamitani et al., 2009 | ||

| Induces PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation | Krahling et al., 2008 | |||||

| Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus (IBV) | ND | ND | Induces PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation at early stages of infection and inhibits eIF2α phosphorylation at later stages | Wang X. et al., 2009; Liao et al., 2013 | ||

| Viral 5b protein induces host translational shutoff | Kint et al., 2016 | |||||

| Arteriviridae | Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) | Yes (canonical) |

ND | Induces PERK-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation and subsequent SGs assembly | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| Induces Mnk1-mediated eIF4E phosphorylation | Royall et al., 2015 | |||||

| Induces PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation, but translation repression is PKR-independent | Fritzlar et al., 2019 | |||||

| G3BP-1 is sequestered to RFs even in presence of arsenite treatment | Fritzlar et al., 2019 | |||||

| G3BP-1 colocalizes with Nsp3 in a perinuclear zone but not in presence of arsenite treatment | Brocard et al., 2018 | |||||

| Feline Calicivirus (FCV) | No | Yes | NS6-mediated G3BP-1 cleavage | Humoud et al., 2016 | ||

| (-)ssRNA | Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A virus (IAV) | No | Yes | NS1 restrict SG assembly dependent on eIF2α while NP and PA-X block SG assembly in an eIF2α-independent manner | Khaperskyy et al., 2014 |

| PA-X requires its endoribonuclease activity to inhibit SGs, and relocalizes PABP1 to the nucleus | Khaperskyy et al., 2014 | |||||

| PA-X selectively degrades host spliced RNAs | Gaucherand et al., 2019 | |||||

| NS-1 inhibits PKR activation by binding to dsRNA | Khaperskyy et al., 2011 | |||||

| NS1 interacts with RAP55 and its RNA and PKR binding sites are required for the interaction and to inhibit SGs | Mok et al., 2012 | |||||

| NS1 and NP interact with DDX3 | Raman et al., 2016 | |||||

| NP and RIG-I are recruited to SGs on ΔNS1 IAV infection, and IAV genomic RNA is sufficient to form SGs | Onomoto et al., 2012 | |||||

| NS1 interacts with NF90 and restricts its binding to PKR. The NS1 RNA-binding domain and the NF90 double-stranded RNA binding domain are required | Wen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016 | |||||

| NF90 binds NP independently of RNA binding | Wang P. et al., 2009 | |||||

| Influenza B virus (IBV) | No | Yes | NS1 is required to inhibit SG assembly. RIG-I and DDX6 interact and colocalize to ΔNS1-induced SGs | Núñez et al., 2018 | ||

| Arenaviridae | Junin Virus (JUNV) | No | Yes | NP and GPC individually impair arsenite-induced SGs by inhibiting eIF2α phosphorylation | Linero et al., 2011 | |

| NP interacts with G3BP-1, PKR, hnRNP A1, and hnRNP K, G3BP-1 and eIF2α. NP sequesters PKR into RFs | King et al., 2017 | |||||

| NP interacts with DDX3 | Loureiro et al., 2018 | |||||

| dsRNA activates PKR and colocalizes with RFs | Mateer et al., 2018 | |||||

| Rhabdoviridae | Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) | Yes (atypical) |

Yes | Inhibit canonical SGs but induces SGs-like structures containing PCBP2, TIA1, TIAR, and viral RNA, P and NP proteins | Dinh et al., 2012 | |

| Rabies virus | Yes (canonical) |

No | SG assembly is dependent on PKR and they locate close to RFs. Viral mRNA is transported to RFs | Nikolic et al., 2016 | ||

| Paramyxoviridae | Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | Yes (canonical) | Yes | 10–25% of infected cells form SGs dependent on PKR | Lindquist et al., 2010, 2011 | |

| Just 1% of infected cells form SGs. The 5‘trailer region of the RSV genome is required to inhibit SGs | Hanley et al., 2010 | |||||

| Just 5% of infected cells form SGs. Sequestration of OGT into RFs suppresses SGs accumulation | Fricke et al., 2012 | |||||

| Measles virus (MeV) | No | Yes | Viral C protein inhibits SG assembly by blocking PKR activation but requires the presence of ADAR1 | Okonski and Samuel, 2012 | ||

| MeV C protein reduces the dsRNA in the cytoplasm to inhibit PKR activation | Pfaller et al., 2013 | |||||

| Sendai virus (SeV) | Yes (canonical) |

Yes | 5–15% of infected cells form SGs. The trailer RNA region captures TIAR and inhibit SGs accumulation | Iseni et al., 2002 | ||

| Viral C protein is required to inhibit SG assembly | Yoshida et al., 2015 | |||||

| Newcastle disease virus (NDV) | Yes (canonical) |

No | NDV replication induces canonical SGs which contain vRNA(+) and RIG-I | Oh et al., 2016 | ||

| SG assembly is dependent on PKR/eIF2α pathway. SGs contain cellular mRNA but no viral mRNA | Sun et al., 2017 | |||||

| Mumps virus (MuV) | Yes (canonical) |

No | SG assembly is dependent on PKR. MuV replicates independently of the presence or absence of SGs | Hashimoto et al., 2016 | ||

| Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) |

Yes | No | PKR-dependent SGs are induced by viral mRNA. SGs have an inhibitory role in HPIV3 replication. | Hu et al., 2018 | ||

| Bunyaviridae | Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) | Yes | Yes | Attenuate Atk/mTOR signaling | Hopkins et al., 2015 | |

| Andes hantavirus (ANDV) | ND | Yes | N protein inhibits PKR activation | Wang and Mir, 2014 | ||

| Filoviridae | Ebola virus | Yes (IB granules) |

Yes | Ebola inhibits canonical SGs but form IB granules within RFs that contain eIF4G, eIF3, PABP, and G3BP-1, but no TIA-1 | Nelson et al., 2016 | |

| VP35 inhibit canonical and stress-induced SGs, and its C-terminal domain is required. VP35 interacts with G3BP-1, eIF3, and eEF2 | Le Sage et al., 2016 | |||||

| ssRNA-RT | Retroviridae | Human T-cell Leukemia virus (HTLV-1) | No | Yes | Tax interacts with HDAC6 and USP10 | Legros et al., 2011; Takahashi et al., 2013 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) | No | Yes | Staufen 1 and Gag-mediated blockade of SGs assembly | Abrahamyan et al., 2010 | ||

| Gag interacts with eEF2 to block SGs assembly | Valiente-Echeverría et al., 2014 | |||||

| G3BP-1 interact with Gag to disassembly preformed SGs | Valiente-Echeverría et al., 2014 | |||||

| gRNA promote pre-translation initiation complex assembly | Soto-Rifo et al., 2014 | |||||

| Gag interacts with eIF4E to promote disassembly of SGs | Cinti et al., 2016 | |||||

| Ectopically expressed NC protein induces eIF2α phosphorylation and interacts with SGs proteins. | Rao et al., 2017 | |||||

| Human immunodeficiency virus type 2(HIV-2) | Yes | No | gRNA and TIAR colocalizes in SGs | Soto-Rifo et al., 2014 | ||

| Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV) | ND | ND | YB-1 interacts with Gag and gRNA in cytoplasmic foci | Bann et al., 2014 |

Viral Infections and Processing Bodies

PBs are membraneless organelles and their diameter range between 150 and 340 nm (Cougot et al., 2012). PBs contain proteins involved in mRNA decapping machinery (Dcp1/2, LSm1-7, Edc3 proteins), scaffolding proteins (GW182, Ge-1/Hedls), deadenylation factors (Ccr1, Caf1, Not1), nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) proteins (SMG5-6-7, UPF1) and translation control factors (CPEB, eIF4E-T) (reviewed in Poblete-Durán et al., 2016). PBs are constitutively assembled in the cytoplasm of the cell, but their size and number increases upon cellular stress (Kedersha et al., 2005). Initially it was suggested that PBs were sites of mRNA decay, but recent evidences suggest that instead, P-bodies are sites of long-term mRNA storage and decapping enzymes (reviewed in Luo et al., 2018). Recent studies have shown that PBs participate in the storage of a selection of mRNAs; transcripts involved in regulatory processes are enriched while mRNAs that encode proteins that support basic cell functions are excluded (Hubstenberger et al., 2017; Standart and Weil, 2018).

Interestingly, viruses have been shown to modulate PB assembly by degrading and/or relocating PB-associated components, thus avoiding their accumulation. Here we summarize how viruses modulate PBs.

Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA)Viruses

Adenoviridae

In order to accumulate late mRNAs, adenovirus decreases the number of PBs in the cell by relocalizing several PB components, such as DDX6, LSm1, Ge-1, Ago2, and Xrn1 to aggresomes, where proteins are inactivated or degraded (Greer et al., 2011). Aggresome formation is induced by the viral protein E4 11K, which was found to specifically bind DDX6, suggesting that this interaction may redistribute DDX6 (Greer et al., 2011). Recently, the PB-associated protein PatL1 was also shown to localize within aggresomes following E4 11K protein expression (Friedman and Karen, 2017).

Herpesviridae

In contrast to the aforementioned adenovirus, expression of PB-associated proteins and PBs accumulation increase upon HCMV infection, but viral mRNA is not targeted to them, suggesting that HCMV mRNAs escape translation repression (Seto et al., 2014). HCMV-induced PB assembly requires cellular but no viral RNA synthesis and was independent of the translational status of the cell (Seto et al., 2014). KSHV prevents PB assembly during latent and lytic infection thanks to the activation of the cytoskeletal regulator RhoA GTPase (RhoA) (Corcoran et al., 2012, 2015). How RhoA disperse PBs is unknown, but in both cases its activated by the p38/MK2 pathway, which is triggered by the viral gene G-protein-coupled receptor (vGPCR) during lytic infection, and by the viral kaposin B (KapB) protein during latency (Corcoran et al., 2012, 2015). Furthermore, on both cycles PBs inhibition causes stabilization of AU-rich containing RNAs, a cis-acting RNA element usually present in mRNAs coding cytokines, growth factors and proto-oncogenes, increasing their protein synthesis during infection (Corcoran et al., 2012, 2015).

Double-Stranded RNA (dsRNA) Viruses

Reoviridae

Similarly, rotavirus has also been shown to suppress PB assembly (Montero et al., 2008; Bhowmick et al., 2015). Upon infection, it reduces the cytosolic levels of Xrn1, Pan3, and Dcp1a, but no GW182 in a time-dependent manner (Bhowmick et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has been shown that rotavirus infection induces the relocalization of Xrn1, Dcp1a, and PABP to the nucleus (Montero et al., 2008; Bhowmick et al., 2015), and to sequester most of the PB components into RFs, with the exception of DDX6, Edc4, and Pan3 (Dhillon and Rao, 2018; Dhillon et al., 2018), and to accelerate Pan3 decay by the NSP1 protein (Bhowmick et al., 2015).

Positive-Sense Single Stranded RNA ((+) ssRNA) Viruses

Flaviviridae