Abstract

Gentamicin, one of the most widely used aminoglycoside antibiotics, is known to have toxic effects on the inner ear. Taken up by cochlear hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs), gentamicin induces the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and initiates apoptosis or programmed cell death, resulting in a permanent and irreversible hearing loss. Since the survival of SGNs is specially required for cochlear implant, new procedures that prevent SGN cell loss are crucial to the success of cochlear implantation. ROS modulates the activity of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, which mediates apoptosis or autophagy in cells of different organs. However, whether mTOR signaling plays an essential role in the inner ear and whether it is involved in the ototoxic side effects of gentamicin remain unclear. In the present study, we found that gentamicin induced apoptosis and cell loss of SGNs in vivo and significantly decreased the density of SGN and outgrowth of neurites in cultured SGN explants. The phosphorylation levels of ribosomal S6 kinase and elongation factor 4E binding protein 1, two critical kinases in the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway, were modulated by gentamicin application in the cochlea. Meanwhile, rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTORC1, was co-applied with gentamicin to verify the role of mTOR signaling. We observed that the density of SGN and outgrowth of neurites were significantly increased by rapamycin treatment. Our finding suggests that mTORC1 is hyperactivated in the gentamicin-induced degeneration of SGNs, and rapamycin promoted SGN survival and outgrowth of neurites.

Keywords: gentamicin, spiral ganglion neurons, ototoxicity, mammalian target of rapamycin, inner ear

Introduction

Gentamicin, one of the most frequently used aminoglycoside antibiotics, is known to cause severe hearing loss in different species, including human beings (Selimoglu 2007; Warchol 2010; Jiang et al. 2017). After gentamicin is taken up by cochlear sensory cells, formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and dysfunction of mitochondria are observed in the cochlear sensory cells, resulting in apoptosis or programmed cell death (Warchol 2010; Jiang et al. 2017). It is well established that these cellular processes and resulting dysfunction and degeneration of cochlear hair cells (HCs) and spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) are responsible for consequent hearing loss. The loss of SGNs impairs the transmission of neural signal carrying the sound information. The survival of SGNs is required for the cochlear implant and the hearing recovery of patients. Several molecular pathways were proposed to be involved in the degeneration of HCs and SGNs (Ding et al. 2012). However, the mechanisms at the molecular level remain obscure in gentamicin-induced degeneration of cochlear sensory cells. Investigation of the signaling pathways involved in gentamicin ototoxicity may lead to new procedures that prevent hearing loss induced by this common antibiotic.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an intracellular kinase, widely expressed in cells of mammalian organs or tissues (Laplante et al. 2012). It binds with the unique adaptor proteins raptor or rictor to form two independent mTOR complexes (mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively). The mTOR signaling pathway plays an essential role in cell growth, cell proliferation and division, cell metabolism, and repair (Wullschleger et al. 2006; Laplante et al. 2012). This signaling pathway is also involved in response to cellular stress, regulating cell death during apoptosis or autophagy (Laplante et al. 2012). Studies of ROS-induced cell death indicate that mTORC1 was involved in this process (Li et al. 2010; Laplante and Sabatini 2012). However, the information about the role of mTOR signaling in the inner ear is very limited. The aim of our study is to investigate whether mTOR signaling is involved in gentamicin-induced ototoxicity.

Rapamycin is a specific inhibitor of mTORC1. In several studies, it protects types of cells from degeneration or death during damage, aging, or disease (Wullschleger et al. 2006; Pan et al. 2012). For example, rapamycin protects neurons from death in both cellular and animal toxin models of Parkinson disease (PD) and from drug-induced apoptosis in PC12 cell lines (Malagelada et al. 2010; Park et al. 2017). In another study, rapamycin decreased the death rate of cell lines under ultraviolet and hydrogen peroxide-induced ROS stimulation (Li et al. 2010). In the present study, we observed SGN degeneration under gentamicin application both in vivo and in vitro. Ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) and elongation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1), two critical downstream targets in mTORC1 signaling pathway, were modulated by gentamicin application. We employed SGN organotypic explants to evaluate the effects of rapamycin on SGN survival and neurite outgrowth. We found that rapamycin pretreatment protected SGNs from gentamicin-induced degeneration in a dose-dependent manner in vitro.

Methods and Material

All of the studies were performed in accordance with the Chinese Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, and permission was obtained from the Southern Medical University Laboratory Animal Center.

Animal Care and Systematic Gentamicin Application

Both sexes of adult (7–9 weeks) C57/BL6J mice were used to systematically investigate gentamicin-induced ototoxicity. Animals were housed in a normal sound environment on a 12-h (h) light/12-h dark schedule and had free access to water and a standard diet. For gentamicin application, 200-mg/kg gentamicin sulfate was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) 20 min after furosemide treatment (40 mg/kg, i.p.). This protocol of gentamicin treatment was modified from a preview study (Ding et al. 2010). Co-administration of gentamicin and furosemide was applied once daily for 15 days. In the control group, 5-ml/kg saline was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) once daily for 15 days.

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) Recording

A 24-h rest was allowed for mice to recover from co-administration of gentamicin and furosemide before ABR measurements. The ABRs were obtained before and 1 day after the 15 days of gentamicin or saline application (Fig. 1a). For ABR recording, the methods were described in our previous study (Hang et al. 2016). In brief, mice were anesthetized (sodium pentobarbital, 30 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed on an antivibration table in a soundproof room. A heating pad was used to maintain the animal’s body temperature at 37 °C during ABR recordings. A subdermal needle electrode (recording electrode) was located over the skull vertex, and the reference and ground electrodes were placed ventrolaterally to the external pinna. Tone bursts (1-ms rise/fall, 3-ms plateau) of various frequencies of 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40 kHz were delivered using a calibrated loudspeaker (ES1, Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) located 10 cm away from the animal. The sound intensity was varied 0–90-dB SPL at 5-dB interval. TDT system3 hardwares and BioSigRP software (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) were used to generate and deliver the tone bursts randomly at a rate of 10 bursts/s. The ABR signals were amplified, filtered (100–1000 Hz) and averaged (256 times) using TDT System3 and recorded by BioSigRP software. The averaged ABR waveforms were stored by BioSigRP software for offline analysis. The ABR thresholds were defined as the minimum sound intensity at which averaged waveforms could be distinguished.

Fig. 1.

Intraperitoneal injection of gentamicin elevates the ABR threshold. a Diagram of gentamicin administration. ABRs were examined before and after intraperitoneal injections with gentamicin once daily for 15 days. b The ABR threshold-frequency tuning curves obtained before and after 15 days of saline (left) or gentamicin (right) application. All data points are mean ± SD. n = 12 for saline group and n = 12 for gentamicin group

Dissection and Organotypic Culture of SGNs

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, i.p.) and decapitated. The skull was opened along the sagittal midline, and the brain was removed to obtain the inner ear. Under the dissection microscope, fine forceps was used to remove the bony capsule of the cochlea in the ice-cold Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Life Technologies, USA). Starting from the apical turn, we cut the cochlea into three pieces evenly.

The procedures for organotypic culture of SGNs were modified from the methods described in Yu’s study (Yu et al. 2013). In brief, C57BL/6 mice (either sex) at post-natal day 0 (P0) or P1 were anesthetized with ice; the cochlear tissue was dissected. The organ of Corti and associated stria vascularis (SV) were unwrapped from the modiolus. Starting from the apical turn, apical, middle, and basal turns of modiolus were cut. The organotypic SGN explants were cultured on plastic coverslips coated with 0.1-mg/ml poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in serum-free culture medium DMEM at 37 °C. After 4 h, the medium was replaced by culture medium (neurobasal medium supplemented with 2 % B27, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator. For gentamicin application, 50-μM gentamicin was supplemented after 10-h culture. For rapamycin treatment, 5- or 15-μM rapamycin was supplemented from the beginning, and 0.1 % DMSO was added as a control. For rapamycin pretreatment, rapamycin of different concentrations (5 μM, 500 nM, 50 nM, and 5 nM) was supplemented from the beginning, and 50-μM gentamicin was added 10 h later. For all cultures, immunostaining was performed 72 h later to morphological examination.

Histopathology and Immunostaining

Right after the final ABR recording, the animals were decapitated, and the cochleae were collected and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde overnight. Decalcification was performed for 72 h at 4 °C with 4 % ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) in PBS, followed by gradual dehydration in glucose (20 % for 24 h, 30 % for 24 h). After decalcification and dehydration, the tissues were embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura, Japan). Consecutive mid-modiolar cochlear resin sections (20 μm in thickness) were cut with a microtome (CM1950; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and the complete mid-modiolar cochlear sections were selected for further analyses. For SGN counting, usually four Rosenthal’s canals could be observed. Along the length of the cochlea, their locations were defined as apical, middle (basal-middle and apical-middle), and basal canals. SGNs in different locations were counted in the same section. The cochlear sections were stained with a Nissl staining kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and examined with a light microscope (BX53, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For immunostaining, after 5-min post-fix, the cochlear sections were permeabilized (0.3 % Triton X-100 in PBS) and blocked with 10 % goat serum for 2 h at room temperature (RT). The sections were incubated with different primary antibodies (caspase 3, 1:100, Proteintech, Chicago, IL); p4EBP1 (Phospho-Thr46), 1:100, BBI Life Science, Shanghai; p-p70S6K (Phospho-T389), 1:100, Bioworld, MN) at 4 °C overnight. In SGN explants, the culture was fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After permeabilization and blocking, the culture was incubated with primary antibody for Class III β-Tubulin (TUJ-1, 1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 4 °C overnight. After washing the primary antibody out with PBS, the tissues were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000; BBI Life Science, Shanghai, China) in blocking solution at RT for 2 h. The stained sections and cultures were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade mounting reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on a glass slide. The fluorescence images were acquired using a confocal microscope (A1+, Nikon, Japan).

Western Blotting

Right after ABR recording, the animals were decapitated, and the cochleae were collected for western blotting assay. Usually, 75–100-μg protein could be extracted from one modiolus. In the experiment, modiolar protein from two cochleae of the same mouse was combined to get enough protein. Cultured SGN explants were also collected for western blotting assay. Three SGN explants (apex, middle, base) dissected from the same cochlea were combined for protein extraction. Usually, 50–80-μg protein could be extracted from one sample. Western blot was performed as described in our previous study (Li et al. 2014). In brief, the proteins of modiolus and SGN explants were extracted in the radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, WI, USA), and 15- (for cultures) or 50- (for modiolus) μg protein of each sample was separated by 12 % SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking with 5 % non-fat milk in TBS-T (20-mM Tris, 137-mM NaCl, and 0.1 % Tween-20, pH 7.6) for 2 h at RT, the membrane was incubated with the primary antibodies (anti-4EBP1, anti-p4EBP1(Phospho-Thr46), 1:500; anti-p70S6K, 1:500, Proteintech, Chicago, IL; anti-p-p70S6K (Phospho-T389), Bioworld, MN, USA, 1:250; anti-caspase 3, 1:500, Proteintech, Chicago, IL) overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit (1:1000) or anti-mouse (1:1000) IgG conjugated to the HRP (BBI Life Sciences, Shanghai, China). The immunobands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) and visualized with a chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Image 600, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Protein grayscale was analyzed with Image analysis software (ImageQuantTL, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL).

Data Analysis

For cultured SGN explants, the fluorescence images were acquired using Z-scan with a step of 0.75–1 μm between each plane. ImageJ (NIH Image, Bethesda, MD) was used to calculate the density of the neurites. At least three regions (each region was at least 150 μm along the cochlear segment) were counted from each image. Imaris 8.0 (BitPlane, Switzerland) software was used to calculate the length of SGN neurites. The quantitative analyses were performed in a blind manner by two independent investigators to ensure the consistency of measurement. SPSS 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis. The Student’s t test (for comparison of two groups) and one-way ANOVA analysis (LSD t test, post hoc comparisons for comparison of multiple groups) were used to examine the significance between different groups. Significance was defined as 푝 < 0.05. GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for plotting.

Results

Gentamicin Induces SGN Loss and Activation of mTORC1 Signaling In Vivo

It is well-accepted that gentamicin application can cause severe hearing loss in rodents (Selimoglu 2007; Jiang et al. 2017). In the present study, ABR to tone bursts were examined before and 1 day after 15 days of gentamicin application (200 mg/kg, i.p.) in 20 adult C57 mice (Fig. 1a). In the control group, saline was injected in 12 mice (5 ml/kg, i.p.) for 15 days. As shown in Fig. 1b, no effect of saline on ABR thresholds or age-related hearing loss was observed at day 16 (repeat measures, general linear model, F(1,22) = 0.737, p > 0.05). After 15 days of gentamicin administration, 12 of 20 mice (7 of 10 males and 5 of 10 females) showed 15–35-dB elevation of ABR thresholds at day 16. These mice were considered animals with hearing loss and were used in further analyses. Figure 1b shows that at all stimulating frequencies tested, the mean ABR thresholds of the 12 mice were significantly higher after (post-Gent.) gentamicin administration compared with those before (pre-Gent.) gentamicin administration (repeat measures, general linear model, F(1,22) = 11.688, p < 0.001). Our results indicate that the level of hearing loss induced by gentamicin application varied in different animals.

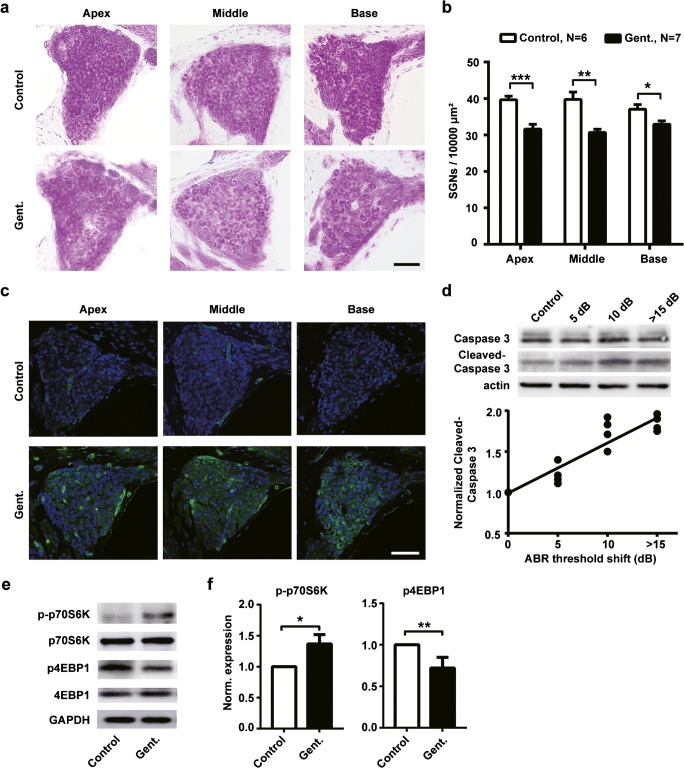

We then examined the effects of intraperitoneal injection of gentamicin on SGNs. As shown in representative images, we labeled the SGNs in the cochlear sections with Nissl staining (Fig. 2a). Quantitative analysis showed a significant decrease in SGN densities in gentamicin animals (Gent.) at all locations of the cochlea compared to control animals (Fig. 2b; apex: t(11) = 4.867, p < 0.001; middle: t(11) = 3.344, p = 0.007; base: t(11) = 2.686, p = 0.02).

Fig. 2.

Intraperitoneal injection of gentamicin induces cell loss of spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs). a Nissl staining of SGNs in representative cochlear sections from different locations (apical, middle, and basal) from gentamicin and control animals. Scale bar = 50 μm. b The density of SGNs at different cochlear locations. Gentamicin application significantly decreased the density of SGNs (n = 7 for gentamicin group, n = 6 for control group). Data points are mean ± SEM. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001. c Representative confocal microscope images show cleaved-caspase 3 expression was increased in SGNs after gentamicin administration. Cleaved-caspase 3 was labeled in green. The nuclei were labeled in blue. Scale bar = 50 μm. d Cleaved-caspase 3 expression correlates with the degree of gentamicin-induced hearing loss. Upper panel: immunobands of caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 3 in control (saline) mice (n = 6) and gentamicin mice with 5 (n = 4), 10 (n = 4), and > 15 dB (n = 4) hearing loss. Lower panel: correlation analysis between hearing loss and expression of cleaved-caspase 3, R2 = 0.94, p = 0.03. The experiment was repeated 4 times for each group. e Immunobands of p70S6k and 4EBP1 of cochleae from gentamicin (Gent.) and control mice. f Normalized expression level of p- p70S6k (left) and p-4EBP1 (right). The experiment was repeated three times in each group. All data points present as the mean ± SD. Control, n = 6; Gent., n = 6. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01

Under the ototoxicity induced by gentamicin, apoptosis was usually observed in SGNs, leading to dysfunction and cell loss (Selimoglu 2007; Bae et al. 2008; Jeong et al. 2010). Therefore, we examined the expression of caspase 3, an apoptosis-related protein, in SGNs. The immunoflourescence signals of cleaved caspase 3 were inspected in the cochlear sections from six animals with hearing loss after gentamicin administration and from seven control animals. As shown by representative images in Fig. 2c, immunoflourescence signals of cleaved caspase 3 in gentamicin-treated animals are stronger than those in control animals. Western blots of caspase 3 were further performed to evaluate the expression of cleaved-caspase 3 in different animals separately. Severe loss of SGNs may affect the level of caspase 3 in cochleae of mice with > 15 dB− hearing loss (n = 4, 2 males and 2 females). Therefore, the caspase 3 was also examined in cochleae from animals with less hearing loss (5 dB−, n = 4, 2 males and 2 females; 10 dB−, n = 4, 1 male and 3 females) and control mice (n = 6, 3 males and 3 females) (Fig. 2d, upper panel). The normalized expression of cleaved-caspase 3 increased with the increasing degree of hearing loss. The correlation between the two values (R2 = 0.94, p = 0.03) is shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2d.

p70S6K and 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) are known as key factors in the mTOR pathway. The phosphorylation status of these proteins was used to assess mTORC1 activity (Li et al. 2010). In order to determine whether mTORC1 pathway was activated by gentamicin administration, we examined the changes of phosphorylated p70S6K (p-p70S6K) and p4EBP1 in cochleae from animals with at least 15 dB− hearing loss (n = 6, 3 males and 3 females). Figure 2f, e shows that the expression levels of p-p70S6K were significantly increased by gentamicin administration (t(4) = 4.158, p = 0.014), whereas the levels of p4EBP1 were significantly decreased (t(4) = 5.196, p = 0.007).

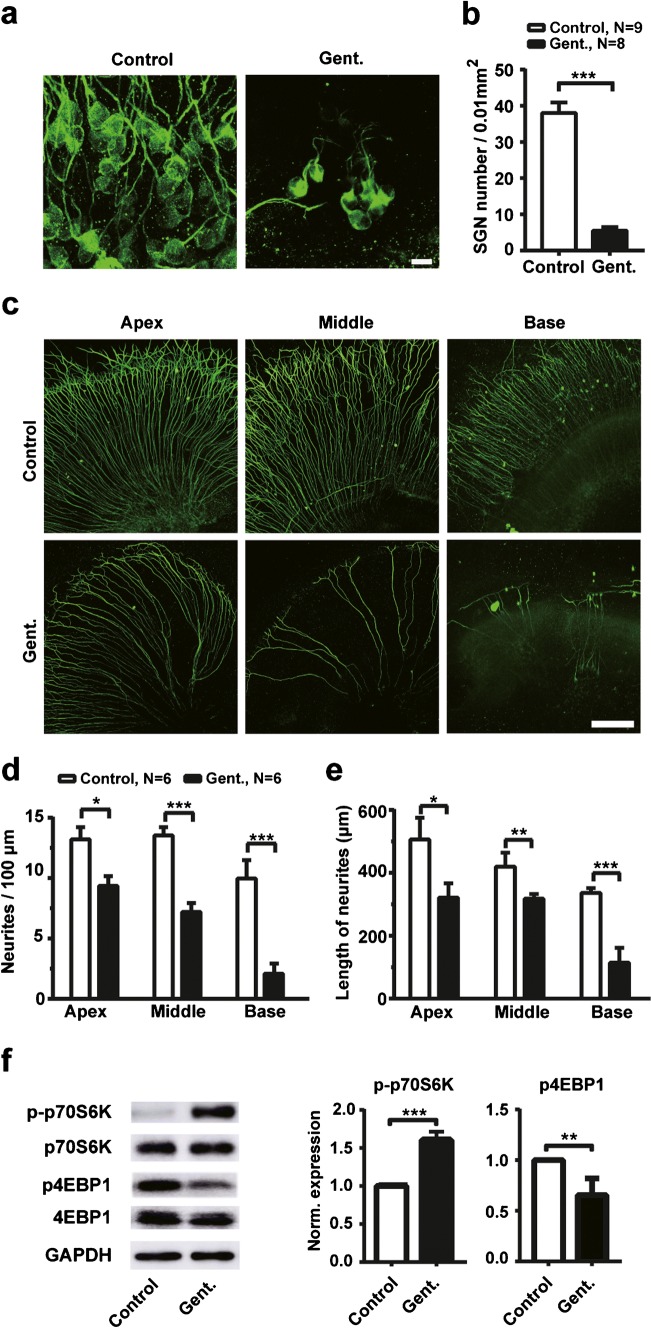

Gentamicin-Induced Degeneration of SGNs In Vitro

In the present study, hearing loss was only observed in 60 % (12 of 20 mice) animals after 15 days of gentamicin injection. However, for those animals with hearing loss, the sign of degeneration was observed in SGNs. Next, we examined the density of SGNs and their neurites in SG explants to evaluate the effects of gentamicin on the survival of SGNs and the outgrowth of neurites in vitro. As shown by representative confocal images in Fig. 3a, we found that the SGN soma is much less after 72-h presence of gentamicin (50 μM) in cultures. Compared with control cultures (n = 9), the mean SGN soma density was significantly decreased by gentamicin treatment (n = 8, t(15) = 8.622, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c shows representative confocal images of the neurites labeled with TUJ-1 in organotypic cochlear cultures with (Gent.) or without (control) exposure to 50-μM gentamicin for 72 h. The mean neurite densities (Fig. 3d; apex: t(10) = 3.002, p = 0.013; middle: t(10) = 5.383, p < 0.001; base: t(10) = 6.653, p < 0.001) and lengths (Fig. 3e; apex: t(10) = 2.791, p = 0.019; middle: t(10) = 3.196, p = 0.009; base: t(10) = 4.605, p < 0.001) of SGN explants from different modiolar positions were significantly decreased by gentamicin administration (n = 6) compared with control cultures (n = 6).

Fig. 3.

Gentamicin induces degeneration of SGNs in SGN explants. a Representative confocal images of SGNs under 50-μM gentamicin (Gent.) treatment and control conditions. The SGN soma was labeled with TUJ-1 (green). Scale bar = 10 μm. b The SGN soma densities under gentamicin and control conditions. c Representative confocal images of SGN neurites from different locations of the cochlea under 50-μM gentamicin (Gent.) and control conditions. The SGN neurites were labeled with TUJ-1 (green). Scale bar = 100 μm. d The density of neurites of cultured SGN explants from different turns of the cochlea (n = 6 for each column). e The length of neurites of cultured SGN explants under gentamicin and control conditions (n = 6 for each column). For b, d, and e, all data points are mean ± SEM. f Immunobands (left) and expression level (right two panels) of p- p70S6k and p-4EBP1 from gentamicin (Gent.) treated (n = 6) and control groups (n = 5). The experiment was repeated three times in each group. Data points are mean ± SD. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

To investigate whether mTORC1 signaling is involved in the gentamicin-induced degeneration of SGN explants, we then examined the level of p-p70S6K and p4EBP1 in the SGN explants. After 24 h of 50-μM gentamicin treatment (n = 6), western blot analysis demonstrated the increased p-p70S6K and the decreased p4EBP1 expression in SGN explants when compared with control cultures (n = 5) (Fig. 3f p-p70S6K: t(4) = 9.487, p = 0.001; p4EBP1: t(4) = 5.548, p = 0.005). Together with our in vivo data, our results indicate overactive mTORC1 signaling in SGN, suggesting that dysregulated mTORC1 signaling involved in the degeneration of SGNs induced by gentamicin.

Rapamycin Protects SGNs from Gentamicin-Induced Degeneration In Vitro

Our results suggest the mTORC1 pathway is activated in the SGN by the administration of gentamicin. To determine the role of activated mTORC1 signaling in the occurrence of SGN loss, we examined the effects of rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTORC1, on the SGN explants after 82-h rapamycin treatment. Interestingly, the neurites of SGNs in organotypic cochlear cultures with or without 5-μM rapamycin treatment showed no significant differences (Fig. 4a), implying that the rapamycin at low concentration (5 μM and below) does not affect the survival of SGNs and the outgrowth of SGN neuritis (Fig. 4b, c). However, 15-μM rapamycin treatment alone produced a severe decrease in the number of SGN neurites in cultures from all modiolar positions (Fig. 4a). The mean neurite densities (Fig. 4b; apex: F(2,15) = 17.555, p < 0.001; control vs. 15 μM, p = 0.003; middle: F(2,15) = 10.75, p < 0.001; control vs. 15 μM, p = 0.002; base: F(2,15) = 45.631, p < 0.001; control vs. 15 μM, p < 0.001; n = 6 for each group) and lengths (Fig. 4c; apex: F(2,15) = 10.798, p < 0.001; control vs. 15 μM, p = 0.002; middle: F(2,15) = 27.646, p < 0.001; control vs. 15 μM, p < 0.001; base: F(2,15) = 17.993, p < 0.001; control vs. 15 μM, p < 0.001, n = 6 for each group) of SGN explants were significantly decreased by 15-μM rapamycin administration compared with control cultures (DMSO). Therefore, the protective effects of rapamycin were examined at concentrations of 5 μM and below.

Fig. 4.

Effects of rapamycin at different concentrations in SGN explants. a Representative confocal images of SGN explants from different locations of the cochlea under administration of DMSO (control) or 5 or 15-μM rapamycin. Scale bar = 100 μm. b The density of neurites of cultured SGN explants from different turns of the cochlea (n = 6 for each column). c The length of neurites of cultured SGN explants under rapamycin and control conditions (n = 6 for each column). For b and c, all data points are mean ± SEM. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001; NS, no significance

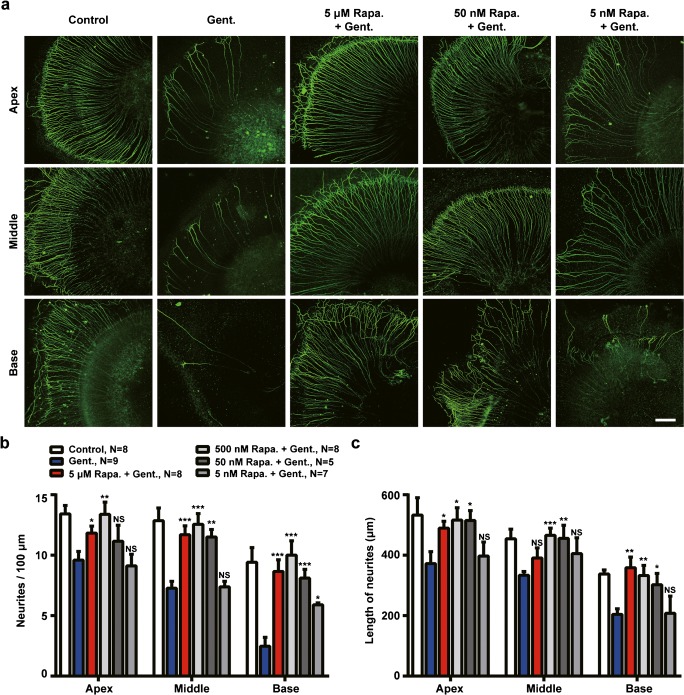

Next, to determine the protective effects of rapamycin, SGN cultures were pretreated with rapamycin at different concentrations for 10 h, followed by 50-μM gentamicin treatment for 62 h. Rapamycin treatment protected against gentamicin induced SGN loss, as shown by the increased survival of SGN in rapamycin-pretreated cultures (Fig. 5a). The quantitative analysis shows the significant increases in the SGN soma density when pretreated by 5 μM (p < 0.001), 500 nM (p < 0.001), and 50 nM (p < 0.01) rapamycin relative to gentamicin-treated cultures (Fig. 5b; F(5,45) = 19.321, p < 0.001). The neurite outgrowth of SGNs was also enhanced by rapamycin treatment. As shown in the confocal images in Fig. 6a, the degeneration of SGN neurites was attenuated by pretreatment with 5-μM and 50-nM rapamycin, compared with those explants treated by gentamicin only (Gent.). The quantitative analysis shows that the decrease in neurite density (Fig. 6b; apex: F(5,39) = 4.111, p = 0.004; middle: F(5,39) = 10.02, p < 0.001; base: F(5,39) = 8.196, p < 0.001) and length (Fig. 6c; apex: F(5,39) = 3.075, p = 0.020; middle: F(5,39) = 4.552, p = 0.002; base: F(5,39) = 4.369, p = 0.003) under gentamicin administration was significantly reduced by pretreatment with rapamycin at 5 μM, 500 nM, and 50 nM. No significant difference was observed between rapamycin-pretreated cultures and controls. However, after pretreatment with rapamycin at lower concentration (5 nM), no protective effects in SGN neurites were observed.

Fig. 5.

The protective effect of rapamycin treatment. a Confocal images of TUJ-1 immunolabeled SGN soma (green) showing survival of SGNs in various concentrations of rapamycin treatment. Scale bar = 10 μm. b SGN soma densities in control, gentamicin only, and rapamycin-treated groups. The number in each column indicates the sample size. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; NS, no significance, tested by the Student’s t test by comparing with corresponding gentamicin treated group

Fig. 6.

Rapamycin treatment protects SGN neurites against gentamicin-induced degeneration in SGN explants. a Representative confocal images of SGN explants from different locations of the cochlea under administration of DMSO (control) or 50-μM gentamicin (Gent.) in the absence and presence of rapamycin treatment at different concentrations. Scale bar = 100 μm. b The density of neurites of cultured SGN explants under gentamicin administration with/without rapamycin treatment. c The length of neurites of cultured SGN explants under gentamicin administration with/without rapamycin treatment. For b and c, all data points are mean ± SEM. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; NS, no significance, tested by the Student’s t test by comparing with corresponding gentamicin treated group

Discussion

In the present study, co-application of gentamicin and furosemide in vivo induced mild hearing loss exhibited as a ~ 20-dB increase in the mean ABR threshold (Fig. 1b). Furosemide (40 mg/kg) was co-applied in order to induce rapid hearing loss by using lower dose of gentamicin. It has been reported that single treatment of furosemide alone can induce significant hearing loss (Li et al. 2011). However, the hearing loss is transient and reversible. A 400-mg/kg furosemide intraperitoneal injection induced a 60-dB ABR threshold shift within 2 h. The ABR threshold recovered to a normal level within 24 h (Li et al. 2011). The ototoxic effects of aminoglycoside antibiotics can be greatly enhanced by co-administration with furosemide. Combined treatments of aminoglycoside antibiotics and furosemide have been used to create animal models with hearing loss. Despite we do not know the exact effect of furosemide alone after our treatment paradigm, we speculate that the gentamicin ototoxicity could cause the degeneration of SGNs. The ototoxic effect of gentamicin is also supported by our in vitro experiments in which gentamicin alone could induce degeneration in SGN explants (Fig. 3).

In the present study, the loss in SGNs was observed after systematic administration of gentamicin (Fig. 2). This result is consistent with a number of previous studies, in which SGN loss was observed by aminoglycoside application in vivo (Jiang et al. 2017). Although SGNs loss is widely reported in sensorineural hearing loss cases caused by aminoglycoside antibiotics, it is not clear how gentamicin treatment induces SGNs death. Is it due to the direct toxic effect of gentamicin on SGNs or the secondary degeneration after HC loss? Despite early ototoxic effect happens in HCs (Ding et al. 2010), functional hearing impairment and HC loss are only observed 10–14 days after the start of daily gentamicin treatments (Hiel et al. 1993). In the present study, significant loss and degeneration of SGNs had been observed after 15 days of gentamicin treatments. This result implies that primary degeneration of SGNs may involve in the gentamicin-induced hearing loss. This conclusion is also supported by our in vitro results. Gentamicin treatment in SGN explants shows significant decrease in the cell density and the length of neurites (Fig. 3), suggesting that gentamicin treatment causes the SGNs loss directly. In our study, we did measure the ABR thresholds to determine the development of gentamicin-induced hearing loss (data not shown). For all animals, the hearing loss became severer as the time increased after treatments. At 3 weeks after completion of treatment, no clear ABR waveforms could be detected at almost all frequencies tested. It is well documented that aminoglycoside-induced HC loss may cause secondary degeneration of SGNs. However, at least 50 % apical outer HCs and almost all inner HCs are remained after 15 days of gentamicin treatment (Ding and Salvi 2005 for review). The severe hearing loss to mid- and low-frequency sounds also suggests the increased primary degeneration of SGNs. We think this finding is significant for the clinical usage of antibiotics, especially for those cochlear implant patients. In the present study, only the degeneration and rescue of SGNs were investigated. The effects of mTOR signal pathway on HCs will be present in next study.

The differences in animal species, the protocol of drug delivery, and especially the drug dosage used (Wu et al. 2001; Ding et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2012; Ruan et al. 2014) may affect the loss of SGNs and HCs. For example, in guinea pigs and chinchillas, gentamicin injection of 250 mg/kg daily for 10 days induced 50–100 % OHC loss in the basal organ of Corti (Ding et al. 2003, 2010). In our preliminary experiments, systematic gentamicin administration at dosages higher than 300 mg/kg caused death in > 50 % animals, similar to Zhao’s study (Zhao et al. 2017). The high death rate maybe due to other adverse effects of gentamicin, such as neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity (Kosek et al. 1974; Selimoglu 2007; Jiang et al. 2017). To use the minimum number of animals, we used a lower dosage in the present study. The dose we used in this study (200 mg/kg) caused approximately 10 % animal death. The exact concentration of gentamicin in the endolymphatic environment was not determined in our experiments. It is possible that the concentration of gentamicin is not high enough to cause severe loss of SGNs because of the existence of the labyrinthine barrier, although furosemide was co-applied in the present study. This conclusion is also supported by similar results reported by other studies (Kujawa and Liberman 2009; Liu et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2017).

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway plays an essential role in normal cellular processes, including cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and repair (Bai and Jiang 2010). This signaling pathway is also involved in cell degeneration during apoptosis or autophagy (McCormick 2004; Laplante and Sabatini 2012; Saqcena et al. 2015). mTORC1 and mTORC2 are two major mTOR functional complexes regulating the downstream kinases. Intracellular signals, including growth factors, mitogens, phosphatidic acid, and environmental cues, including energy, nutrients, and stresses, can active mTORC1. Usually, mTORC1 activation upregulates the phosphorylation of S6K. S6K is a key factor involved in translation initiation. Specific phosphorylation of S6K (p70S6K) regulates protein synthesis and cell death, acting as a negative regulator of neuritis outgrowth (Laplante and Sabatini 2012; Al-Ali et al. 2017). Activated mTORC1 modulates the phosphorylation of 4EBP1. In its phosphorylated state, 4EBP1 facilitates the activity of eukaryotic initiation factor-4E in the initiation of protein synthesis. Interestingly, the hyperactivation of mTORC1 can cause upregulation of p-p70S6K and downregulation of p-4EBP1 and result in cell apoptosis (Toschi et al. 2008; Foster and Toschi 2009; Li et al. 2010), consistent with our observation that gentamicin modulated the phosphorylation of S6K and 4EBP1 and induced degeneration of SGNs (Figs. 2 and 3). In contrast, mTORC2 regulates cell cycle-dependent organization of actin cytoskeleton through AKT activation. The role of mTORC2 activation is still uncertain in the control of cell death. Studies have shown that prolonged treatment with high-concentration rapamycin can also affect mTORC2 (Sarbassov et al. 2006; Foster and Toschi 2009). It has been suggested that mTORC2 may play a more important role in suppressing proliferation and promoting apoptosis (Chen et al. 2003, 2005; Toschi et al. 2008). It is also evidenced by our results that a high concentration of rapamycin-induced degeneration of SGNs in vitro (Fig. 4). Although the detailed mechanisms of how gentamicin modulates mTORC1 and mTORC2 are unknown from the present study and further investigation is still required, our finding suggests that mTOR signaling is involved in the degeneration of SGNs.

Rapamycin, a triene macrolide antibiotic, is a specific inhibitor of mTORC1. A number of studies showed that rapamycin protected against cell death, such as neuronal death in PD and germ cell apoptosis induced by ischemia (Malagelada et al. 2010; Ghasemnejad-Berenji et al. 2017). However, the studies on its role in inner ear cells were limited. It has been reported that rapamycin alleviated cisplatin-induced ototoxicity and hearing loss in vivo. Rapamycin treatment reduced the cisplatin-induced damage of HCs in vivo (Fang and Xiao 2014). It is consistent with our results in SGN explants in vitro (Figs. 5 and 6). In contrast, it is also reported that rapamycin administration resulted in HC damage and decreased outgrowth of neurites in SGNs in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (Leitmeyer et al. 2015). The opposite effects of rapamycin in different studies can be explained by the difference in concentration. In Leitmeyer’s study, 50–100-μM rapamycin was used and directly reached the HCs and SGNs in culture (Leitmeyer et al. 2015). Such a high concentration of rapamycin may activate a complex interaction of mTORC1 and mTORC2, resulting in cell death. This result is consistent with our finding that administration of 15-μM rapamycin resulted in a significant decrease in the density and the length of neurites of SGNs in vitro (Fig. 4). In our study, rapamycin in concentration from 50 nM to 5 μM did not influence the outgrowth or formation of SGN neurites and protected SGNs from gentamicin-induced degeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 973 Program of China (grant number 2014CB943002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31500841), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (grant number 2017A030313178), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT16R37), and Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant number A2015445).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cuixian Li, Email: licxian@smu.edu.cn.

Jie Tang, Email: jietang@smu.edu.cn.

References

- Al-Ali H, Ding Y, Slepak T, Wu W, Sun Y, Martinez Y, Xu XM, Lemmon VP, Bixby JL. The mTOR substrate S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) is a negative regulator of axon regeneration and a potential drug target for central nervous system injury. J Neurosci. 2017;37:7079–7095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0931-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae WY, Kim LS, Hur DY, Jeong SW, Kim JR. Secondary apoptosis of spiral ganglion cells induced by aminoglycoside: Fas-Fas ligand signaling pathway. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1659–1668. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817c1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Jiang Y. Key factors in mTOR regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:239–253. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zheng Y, Foster DA. Phospholipase D confers rapamycin resistance in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:3937–3942. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Rodrik V, Foster DA. Alternative phospholipase D/mTOR survival signal in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:672–679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xiong S, Liu Y, Shang X. Effect of different gentamicin dose on the plasticity of the ribbon synapses in cochlear inner hair cells of C57BL/6J mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:487–494. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Salvi R. Review of cellular changes in the cochlea due to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Volta Rev. 2005;105:407–438. [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Mcfadden SL, Browne RW, Salvi RJ. Late dosing with ethacrynic acid can reduce gentamicin concentration in perilymph and protect cochlear hair cells. Hear Res. 2003;185:90–96. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Jiang H, Salvi RJ. Mechanisms of rapid sensory hair-cell death following co-administration of gentamicin and ethacrynic acid. Hear Res. 2010;259:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Allman BL, Salvi R. Review: ototoxic characteristics of platinum antitumor drugs. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295:1851–1867. doi: 10.1002/ar.22577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang B, Xiao H. Rapamycin alleviates cisplatin-induced ototoxicity in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;448:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DA, Toschi A. Targeting mTOR with rapamycin: one dose does not fit all. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1026–1029. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.7.8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemnejad-Berenji M, Ghazi-Khansari M, Yazdani I, Saravi SSS, Nobakht M, Abdollahi A, Ansari JM, Ghasemnejad-Berenji H, Pashapour S, Dehpour AR. Rapamycin protects testes against germ cell apoptosis and oxidative stress induced by testicular ischemia-reperfusion. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2017;20:905–911. doi: 10.22038/IJBMS.2017.9112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang J, Pan W, Chang A, Li S, Li C, Fu M, Tang J. Synchronized progression of prestin expression and auditory brainstem response during postnatal development in rats. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:4545826. doi: 10.1155/2016/4545826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiel H, Erre JP, Aurousseau C, Bouali R, Dulon D, Aran JM. Gentamicin uptake by cochlear hair cells precedes hearing impairment during chronic treatment. Audiology. 1993;32:78–87. doi: 10.3109/00206099309072930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SW, Kim LS, Hur D, Bae WY, Kim JR, Lee JH. Gentamicin-induced spiral ganglion cell death: apoptosis mediated by ROS and the JNK signaling pathway. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:670–678. doi: 10.3109/00016480903428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Karasawa T, Steyger PS. Aminoglycoside-induced cochleotoxicity: a review. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:308. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek JC, Mazze RI, Cousins MJ. Nephrotoxicity of gentamicin. Lab Invest. 1974;30:48–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Adding insult to injury: cochlear nerve degeneration after “temporary” noise-induced hearing loss. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14077–14085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitmeyer K, Glutz A, Radojevic V, Setz C, Huerzeler N, Bumann H, Bodmer D, Brand Y. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin results in auditory hair cell damage and decreased spiral ganglion neuron outgrowth and neurite formation in vitro. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:925890. doi: 10.1155/2015/925890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhao L, Liu J, Liu A, Jia C, Ma D, Jiang Y, Bai X. Multi-mechanisms are involved in reactive oxygen species regulation of mTORC1 signaling. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ding D, Jiang H, Fu Y, Salvi R. Co-administration of cisplatin and furosemide causes rapid and massive loss of cochlear hair cells in mice. Neurotox Res. 2011;20:307–319. doi: 10.1007/s12640-011-9244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Chen S, Yu Y, Zhou C, Wang Y, Le K, Li D, Shao W, Lu L, You Y, Peng J, Huang H, Liu P, Shen X. BIG1, a brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange factor, is required for GABA-gated Cl(−) influx through regulation of GABAA receptor trafficking. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:808–819. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Jiang X, Shi C, Shi L, Yang B, Xu Y, Yang W, Yang S. Cochlear inner hair cell ribbon synapse is the primary target of ototoxic aminoglycoside stimuli. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:647–654. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagelada C, Jin ZH, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Greene LA. Rapamycin protects against neuron death in in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1166–1175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3944-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccormick F. Cancer: survival pathways meet their end. Nature. 2004;428:267–269. doi: 10.1038/428267a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Nishida Y, Wang M, Verdin E. Metabolic regulation, mitochondria and the life-prolonging effect of rapamycin: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2012;58:524–530. doi: 10.1159/000342204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, Park JH, Ko J, Shin IC, Koh HC. mTOR inhibition by rapamycin protects against deltamethrin-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Environ Toxicol. 2017;32:109–121. doi: 10.1002/tox.22216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Q, Ao H, He J, Chen Z, Yu Z, Zhang R, Wang J, Yin S. Topographic and quantitative evaluation of gentamicin-induced damage to peripheral innervation of mouse cochleae. Neurotoxicology. 2014;40:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saqcena M, Patel D, Menon D, Mukhopadhyay S, Foster DA. Apoptotic effects of high-dose rapamycin occur in S-phase of the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:2285–2292. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1046653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selimoglu E. Aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:119–126. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toschi A, Lee E, Gadir N, Ohh M, Foster DA. Differential dependence of hypoxia-inducible factors 1α and 2α on mTORC1 and mTORC2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34495–34499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800170200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME. Cellular mechanisms of aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:454–458. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32833e05ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WJ, Sha SH, Mclaren JD, Kawamoto K, Raphael Y, Schacht J. Aminoglycoside ototoxicity in adult CBA, C57BL and BALB mice and the Sprague-Dawley rat. Hear Res. 2001;158:165–178. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(01)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Chang Q, Liu X, Wang Y, Li H, Gong S, Ye K, Lin X. Protection of spiral ganglion neurons from degeneration using small-molecule TrkB receptor agonists. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13042–13052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Tai X, Zhai L, Shi L, Chen D, Yang B, Ji F, Hou K, Yang S, Gong S, Liu K. Unitary ototoxic gentamicin exposure may not disrupt the function of cochlear outer hair cells in mice. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137:842–849. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2017.1295470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]