Abstract

Background. Most people with multiple sclerosis (MS) want to be involved in medical decision making about disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), but new approaches are needed to overcome barriers to participation. Objectives. We sought to develop a shared decision-making (SDM) tool for MS DMTs, evaluate patient and provider responses to the tool, and address challenges encountered during development to guide a future trial. Methods. We created a patient-centered design process informed by image theory to develop the MS-SUPPORT SDM tool. Development included semistructured interviews and alpha and beta testing with MS patients and providers. Beta testing assessed dissemination and clinical integration strategies, decision-making processes, communication, and adherence. Patients evaluated the tool before and after a clinic visit. Results. MS-SUPPORT combines self-assessment with tailored feedback to help patients identify their treatment goals and preferences, correct misperceptions, frame decisions, and promote adherence. MS-SUPPORT generates a personal summary of their responses that patients can share with their provider to facilitate communication. Alpha testing (14 patients) identified areas needing improvement, resulting in reorganization and shortening of the tool. MS-SUPPORT was highly rated in beta testing (15 patients, 4 providers) on patient-provider communication, patient preparation, adherence, and other endpoints. Dissemination through both patient and provider networks appeared feasible. All patient testers wanted to share the summary report with their provider, but only 60% did. Limitations. Small sample size, no comparison group. Conclusions. The development process resulted in a patient-centered SDM tool for MS that may facilitate patient involvement in decision making, help providers understand their patients’ preferences, and improve adherence, though further testing is needed. Beta testing in real-world conditions was critical to prepare the tool for future testing and inform the design of future studies.

Keywords: shared decision making, communication, multiple sclerosis, adherence, patient preferences, values clarification, image theory, chronic disease

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive disease of the central nervous system with unpredictable neurologic manifestations that can affect many dimensions of health (e.g., physical, emotional, social).1 Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can slow disease activity, decrease relapse rates, and reduce the accumulation of disability.2,3 MS patients face several difficult decision points during the course of their illness: for example, whether to take steroids for an acute relapse, whether to initiate DMT early in the disease, which DMT to take, and whether to change or discontinue a DMT. DMT options have expanded in recent years to include a range of mechanisms of action, routes of administration (self-injection, infusion, oral), efficacy, adverse effects, and costs.4 The complexity and uncertainties in the evidence surrounding DMT decisions make them appropriate for shared decision making (SDM),5 where treatment decisions are based on the best available evidence and the patients’ health goals, preferences, and values.6

Clinical guidelines for MS2,7 recommend incorporating patient preferences for treatment safety, route of administration, lifestyle, cost, efficacy, adverse effects, and tolerability into DMT decisions. However, doing so can be difficult. Patients often are unclear about their preferences when faced with a new or complex situation and may have difficulty applying their values to health decisions.8,9 Semantic issues arise when terms used to describe preferences (e.g., tolerability, lifestyle, safety) confer different meanings to providers and patients.10 Difficult trade-offs among personal values (e.g., efficacy versus risk) can induce negative emotions that may lead people to avoid or delay decision making or to choose the default option.11,12 Physicians often make assumptions about what matters to patients, but those assumptions are often incorrect.13–16 A variety of approaches have been developed to help patients clarify their values with respect to a treatment decision,17,18 but these approaches typically rely on preference items selected by the developer or physicians, which may not be relevant to patients.19

Patients need trusted, up-to-date information to engage in SDM, but the amount and essential elements of that information are undefined.20 Too much information can interfere with decision making and result in people focusing on only part of the information, screening out information or options based on initial impressions, settling on the first option that appears satisfactory, or using contextual cues to make a choice.21 SDM provides a framework for identifying the types of information needed to facilitate decision making22,23 (e.g., list all options, describe positive and negative features, describe natural history without treatment).19 However, SDM offers little guidance on how to manage a wide range of options and features or how to present information to patients to support decision making.24 In contrast, image theory25 describes how people make complicated value-laden decisions involving multiple options. Image theory depicts decision making as a two-step process. The first step involves focusing on the negative attributes of the options to screen-out options that are incompatible with one’s values and goals. The next step involves examining the pros and cons of each remaining values-compatible option to choose the best one.26 Validated in multiple settings27 and endorsed for SDM,28 image theory informed the design of the SDM tool.

Adherence to DMT is critical to achieve full treatment benefits,29,30 yet adherence is low, ranging from 41% to 95%.31–34 SDM may improve adherence, but the evidence is inconclusive.35 A recent review concluded that SDM can improve adherence to DMTs,36 based in part on a study showing that patients who did not feel well-informed by their neurologist were more likely to be nonadherent.37 SDM may improve adherence to DMTs by helping MS patients and providers choose a DMT that is more consistent with the patient’s treatment goals, preferences, and lifestyles.

The objectives of this study are to 1) describe the development of a patient-centered SDM tool that also targets adherence; 2) describe patient and provider responses to the tool; and 3) discuss challenges in development and implementation.

Methods

Overview

This study is part of a larger mixed-methods study (the MS Decisions Study) to develop and evaluate web-based SDM tools for MS patients. The patient-centered design process was guided by formative work, relevant theory (Table 1),28 and SDM guidance.23 We previously developed10 and validated38 a preference tool to assess patient treatment goals for MS and patient preferences for the attributes of DMTs. That preference tool served as the nucleus for MS-SUPPORT.

Table 1.

Theory-Based Features of MS-SUPPORT

| Theory-Based Recommendation | Feature in Tool |

|---|---|

| Optimize representation. | All preference items and content were derived from and organized by experienced patients. |

| Include all potentially appropriate options and their attributes. | All relevant attributes of all options are shown to patients. |

| Suspend selection of an initially favored options (pre-selection). | Start by focusing only on attributes, not options. Introduce options afterwards. |

| Remind decision maker of the array of values. | Include activities that require attention to the complete array of values (broad and narrow)—choosing, ranking, and rating. |

| Facilitate weighting of attributes. | Force selection of top 3 in importance, then rank, then rate each subcomponent. |

All patient-facing content was co-written and iteratively revised by people with MS and reviewed by experienced providers for scientific accuracy. As part of our development process, people with MS iteratively assessed the tool’s usability (alpha testing); patients and providers iteratively assessed the tool within the context of a clinical MS appointment during beta testing. This study was approved by the New England Independent Review Board. All participants provided written (online) informed consent.

Previous Work Identifying Patients’ Goals and Preferences

Cognitive mapping informed the design of the values clarification modules, using previously published methods.10 In brief, we used the nominal group technique to identify and prioritize patient treatment goals, preferences for DMT attributes, and factors driving a change in treatment. We used card sorting coupled with hierarchical cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling39–42 to create a cognitive map that organized preference items into meaningful clusters. These clusters comprised the lists of goals and preferences included in the values clarification modules and were independently validated.38

The SDM Tool: MS-SUPPORT

MS-SUPPORT is an interactive, online decision aid designed to encourage patient-provider collaboration and promote treatment adherence. The tool emphasizes patient engagement, patient-provider communication, SDM, healthy lifestyles, and treatment adherence. Design features include accessibility on multiple platforms, scalability, encryption, HIPAA compliance, and various options for dissemination and clinical integration. Content can be rapidly updated online. The tool employs principles of effective communication43,44 including positive framing, side-by-side comparisons, graphics, plain language, highlighting important information, and a user-driven path. The average reading level is grade 6.9.45 The tool was created using customized Qualtrics software.

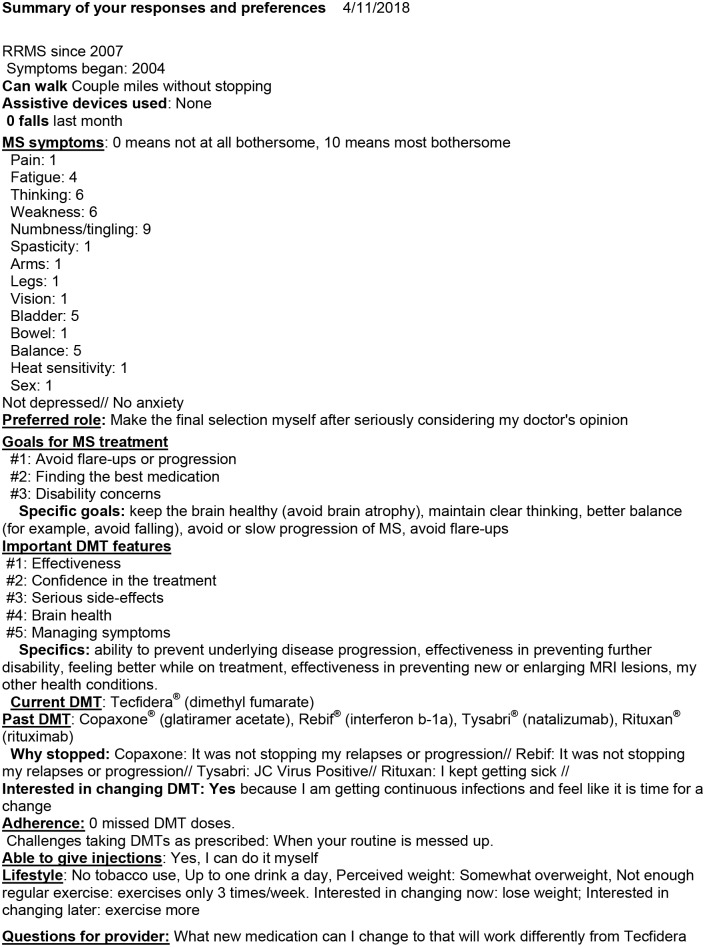

MS-SUPPORT guides users through a series of structured, interactive modules (Figure 1). It provides personalized feedback based on the patient’s stated goals, preferences, needs, situation, adherence, and health behaviors, generating a concise summary that is emailed to the patient to share with their provider (Figure 2). Sharing can be accomplished by printing or emailing the summary, copying it into the electronic patient portal, or using a mobile device. MS-SUPPORT also generates and emails a comprehensive personal report to the patient that includes information on the topics of interest selected by the patient. Patients do not have to complete all the modules at once; they can log back in later to complete the tool.

Figure 1.

Content diagram of MS-SUPPORT. *Summary individualized based on patient responses. Summary and content e-mailed to patient.

Figure 2.

Sample overall summary generated by MS-SUPPORT.

General Tool Design and Rationale

The introductory section of the tool is designed to set the emotional tone, build trust, and promote engagement. It assesses the patient’s role preference in the decision-making process (using the Control Preferences Scale)46 and provides tailored feedback about the importance of engagement and communicating their preferences with their provider.

Values Clarification Exercises

Multitiered values clarification exercises help the user identify and prioritize their MS treatment goals and preferences for DMT attributes by asking the user to select the most important broad goals (or attributes) from a list. Next, the user rates the importance of conceptually related but more specific items within those broad goals (or attributes). Last, additional preference items can be added by the user. Once this exercise is completed, MS-SUPPORT generates a succinct summary of the patient’s goals and preferences and explains how to use goals and preferences to guide decisions. Other preference modules follow a similar design. Values clarification exercises precede discussion of specific DMT options in order to minimize the premature elimination of options that might seem incompatible with one’s values (keeping with image theory).

Defining the Scope and Key Content Messages

During formative work, we became aware of information gaps and misperceptions about MS and DMT that could interfere with informed decision making. To more systematically identify common patient misconceptions and information gaps about DMTs, we convened a very small convenience sample of patients and providers. The sample included five patient advisers who were peer-to-peer educators (e.g., moderating MS blogs and/or support groups) and five experienced MS providers (three medical doctors, one physician assistant, one registered nurse) from different parts of the United States. Advisers independently answered the question, “In your opinion, what do you think are the most important misperceptions and information gaps that interfere with good decision-making about DMTs?” After responding to the question, each respondent was shown responses from previous respondents to stimulate new ideas. They were also asked for suggestions for correcting those gaps and misperceptions (Table 2). Responses guided the content and scope of the tool. For example, because patients did not clearly distinguish between symptom management and slowing disease progression, the tool addressed symptoms as well as DMTs. Because of the many misconceptions regarding lifestyle and DMTs, which could affect symptoms and disease progression, a lifestyle module was included.

Table 2.

Summary of Identified Misperceptions and Information Gaps about MS (Based on Responses from a Convenience Sample of 10 Experienced Providers and Patient Peer Educators)

Respondents were asked to respond to: In your opinion, what do you think are the most important misperceptions and information gaps that interfere with good decision making about DMTs?

| Misperception or Gap | Proposed Solutions Offered by Respondentsa |

|---|---|

| Expectations about DMTs | |

| Best to wait for symptoms to get bad enough before seeking treatment. (“I’m not on anything because I feel good”). | Education, let them know, even when they feel good, they need to stay engaged; use MRI to illustrate the disease ticking away. |

| DMTs don’t make you feel better/don’t improve or cure daily MS symptoms. | Show proof that its working—no new lesions, present DMTs as an insurance plan to protect them from the future but won’t improve their QoL now by treating their symptoms. |

| Expect DMTs to help with symptoms that are gradually worsening (e.g., optic neuropathy, spasticity, walking impairment). | Explain that DMTs are not used to treat these symptoms. |

| Associate DMT with being a cure. | If newly diagnosed and no disability, redefine cure to mean stop the disease dead in its track. Don’t want to oversell what they can do, but don’t become therapeutic nihilists. |

| If one DMT doesn’t work, why bother to try another. This is also a problem among the medical community (perception of therapeutic equivalence among DMTs, reluctance to move people onto a different treatment). | May be a problem only with patients not in the MS loop [lacking specialty MS care]. Especially as we get more DMTs, don’t throw in the towel. |

| Not knowing that there are DMTs available now. | This is only relevant for those who are out of the loop or diagnosed a long time ago. Explain the DMTs that are now available. |

| Not understanding that adherence to treatment matters and affects how well the treatment works, even though there’s no immediate negative repercussion when they miss it. (Some patients may think it’s OK as long as they don’t tell their neurologist.) | Give patients a chance to voice new ADRs, get them to talk about their adherence to therapy, let them know it’s human nature to skip, give them an open forum, say the drug sucks, don’t chastise them about it. Say, “I’m a bad medicine taker myself” then talk about their challenges. Talk about a trickle effect, that there is no immediate return on investment, and no punishment. Sometimes patients do things to make docs happy. |

| Believe that steroids used during a relapse prevent underlying damage. | Steroids are more for quality of life right now, if you can ride it out, it will get you better faster. Ask “Why are we having to use steroids?” then revisit the DMT treatment and the need to change treatments. |

| Understanding risks and side-effects | |

| People don’t understand numbers very well, especially when talking about risk (e.g., what a risk of 1/20,000 v. 1/10,000 means, how to compare it to other risks in our lives). Patients tend to focus on the fact that the risk is there, not on how likely it is, they magnify rare risks and imagine the worst possible case scenario. | There are safety concerns and confusion about interpreting risk. For example, with Tysabri, people think they will get PML, and the patient has already written off a medication because they perceive a potential adverse event as one that they will get. |

| Risk numbers mean different things to different people. What risk of PML is acceptable? People have different risk tolerance. Why introduce the risk of a potentially fatal disease into a condition that is not fatal? Framing matters—if going to sports stadium that holds 70,000, and know that 7 will be shot and killed by a sniper, would I go to the game? Need to reframe to reflect risks of not treating. | |

| First identify why patients are hesitant from a safety perspective. Talk about a medication; if the patient is not open to it, ask why they are hesitant, what makes them nervous about it. People may say, “I read you get PML or get seizures on this med.” Be aware that people get information from lots of different sources. | |

| One provider uses brain atrophy data (not drug specific) to discuss the rate of brain atrophy with and without treatment (0.4 v. 0.1). | |

| Fear about being involved in research. Anything seeming like research or not proven has negative perception. “Are you putting me into a study?” | Address cultural differences. |

| Misunderstand flu-like symptoms, think of them as nausea, vomiting. | Refer to MS consortium guidelines—recently updated, p 20, talks about importance of being on DMT and brain atrophy. |

| People confuse having JCV antibodies with having PML. | Explain that just because the risk is listed doesn’t mean it will happen. PML freaks people out the most. Use risk stratification posters . . . use visual charts to put in perspective, what is your risk of your becoming disabled and progressing if you don’t go on treatment. People are misinformed about safety risk . . . talked about risk tolerance—referring to “big” risks. |

| Perceptions of DMT efficacy | |

| The efficacy of DMTs is related to its mode of administration and/or frequency; drugs taken more frequently are thought to be more effective. Drug can’t be effective if only taken for 6 months. IV meds are stronger than oral meds and get into the body better. Perceptions that pills are the least effective. People thought that Avonex, a weekly IM DMT, was a long-acting form of interferon (e.g., depot form) therefore stronger. | Be clear about efficacy and what influences it. That mode of administration is independent of efficacy. |

| Understanding of MS | |

| Believe their immune system is underactive or weak instead of being overactive, medication side effects not withstanding (“I have a weak immune system”). | Explain that MS results from an overactive immune system. |

| Believe an injury caused their MS, so they don’t have “real MS” or need treatment. People looking for “why me?” | Sometimes there’s a financial motivation to consider, too. For other neurological events too, people tend to tag big things that happen in their life to other big things in their life. |

| Many doctors still present MS as a death sentence, and patients receive it that way. Some docs tell women they can’t or shouldn’t have kids. | If the patient sees MS as being too scary, the patient could shut down, not bother to treat their MS. Try to be positive. |

| Denial, especially about having an aggressive course. | Those in denial won’t be using the tool. Some may have gone through a period of denial. What could the medical community have done differently? Someone can “doc shop” to find a doc to tell them they don’t have MS. There are also MS “groupies” who don’t have MS but are convinced that they do. |

| Perceptions that MS is only a white matter disease (not knowing that lesions can occur in grey matter); thinking that no enhancing lesions mean no progression. | Explain that no new lesions are not same as no white or grey lesions and is not a reason to stop taking DMTs. |

| Disease monitoring | |

| People think that MRIs involve radiation exposure, leading to avoidance of periodic MRI due to perceived risk. | Be clear that MRIs do not involve radiation exposure. |

| Difficultly forecasting adaptation to new situations | |

| Patients don’t think they can’t administer injections, and then have no trouble with them. | Talk about hurdles, fear of injectable meds, how most people easily adapt. |

| Fear of intermittent self-catherization. | |

| Fear of adaptive equipment—think that once I use it, I’m giving in to my progression. | |

| Preparation needed for decision making about DMTs | |

| Not understanding the need to prepare in advance to be involved in decision making about DMTs. | Help people prepare for the visit, give simple pointers, such as list all meds, bring a friend/family. |

| Expect that all the information that is given to patients during the visit will ‘stick’ and have an impact. | Bring a friend to the visit. |

| Expect their MS doctor to make them feel better, get rid of their pain, etc. | If providers try to help with symptom management, the provider is more likely to keep patients engaged for other meds, like DMTs. |

| Underestimate how much their overall physical and mental health affects how they feel on a day-to-day basis. If I feel good, all is OK. | Use the iceberg analogy, that lots goes on under the surface. Encourage someone to come with them to give another viewpoint, patient says they are doing great, friend says otherwise. Adaptation is not the same as being truly stable. |

| Lifestyle: exercise, diet, psychosocial | |

| Thinking that you shouldn’t exercise with MS—stems from the idea that “I have MS and therefore I’m fragile and need to be more sedentary/If I push myself too hard, I’ll push myself into a relapse.” | Explain the benefits of exercise. |

| Exercise will worsen fatigue. | Transiently, exercise may worsen fatigue, but overall the benefits and gains from exercise outweigh that transient feeling. |

| Getting hot can cause damage/If I have heat exposure, that’s causing new lesions, relapse, new damage. | Explain that heat sensitivity is a QOL issues, not related to progression |

| Paleo diet and other extreme diets will cure MS/reverse/stall. | Complementary medicine is challenging. Patients get bombarded by friends, social media, especially dietary. We don’t know what the best diet is. Social media can be a curse . . . read something online, think that’s going to be me. Some have distrust of traditional meds, especially pharma, think that there’s a cure out there that doesn’t involve profit. |

| Thinking that what’s good for one person must be good for you. | Remind people that MS is varied, there is no right magic bullet for everyone. |

| Not understanding that making risky lifestyle choices (binge drinking, smoking, huffing) could interfere with how the DMT works and/or side effects. Patients may not disclose “closet habits” to doctor. | People with MS tend to die from heart disease, cancer, stroke, so overall wellness matters. See NMSS refs. Actuarial tables show that life expectancy is about 7 years shorter. |

| There may not be good data about how affects how the DMT works, but it may well affect adverse drug reactions and adherence. | |

| Not understanding that smoking accelerates MS progression. | Ask about smoking. Give feedback about how it affects the course of MS. |

| Think that psychosocial stress causes disability, and/or relapse, therefore the patient has to isolate oneself from psychosocial stressors because it will make their MS worse. | Talk about the benefits of maintaining positive social relationships. |

DMT, disease-modifying therapy; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis; QoL, quality of life; ADR, adverse drug reaction; JCV, John Cunningham virus, NMSS, National Multiple Sclerosis Society; PML, Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

These include the specific responses and/or thoughts offered by respondents.

Presenting Decisions

DMT decisions were classified as either starting, stopping, or switching treatment, depending on current DMT use. Options were presented to balance the general risks, benefits and inconveniences of DMTs as a class against the risks, benefits and inconveniences of not taking DMTs. The attributes of specific DMTs were subsequently compared. Different graphic representations, including balance scales and flow charts (Figure 3), aided comprehension.

Figure 3.

Screen shots from MS-SUPPORT. Examples of presenting decisions in MS-SUPPORT.

Comparing Options

A simplified table compares the effectiveness and risks of specific DMTs. Using an iterative design process, we initially developed a table comparing each treatment’s relative risk estimate for each benefit and risk, in accordance with SDM guidance.22,23 Despite numerous revisions, we abandoned this approach due to persistent misinterpretation by the testers. Indeed, the scientific evidence does not support head-to-head comparisons among DMTs at this time. Cross-DMT comparisons are confounded by differences in each trial’s comparison group. Providing general information about a treatment’s effectiveness on different outcomes by using a check mark system within the comparison table (Figure 4) proved useful and acceptable to patient and providers.

Figure 4.

Comparing DMT options.

Encouraging Adherence

We developed an adherence module that explains the benefits of adhering to DMTs and addresses individual barriers to adherence. Reasons for nonadherence and strategies for remediation were compiled based on a targeted literature review31–33,47–50 and formative work (e.g., misperceptions about DMTs). This compilation was transformed into self-assessment instruments, each iteratively revised by patients and providers. These instruments assessed the number of recently missed DMT doses, reasons for past nonadherence, and anticipated barriers to future adherence. Tailored feedback addressed problem areas, provided practical tips and resources, and summarized patient responses.

Alpha and Beta Testing

Participants

Participants included non-pregnant, English-speaking patients between the ages of 21 and 75 who self-identified as having MS, were not enrolled in a clinical trial of an MS medication, and had access to the Internet. Beta testing was further limited to patients with an upcoming appointment with their MS provider within 12 weeks.

We initiated an online participant panel for this study in January 2015 composed of participants who were referred to the study (opt-in) through multiple methods, including referrals by participating providers, patient advisers, support groups, and private Facebook groups. All referrals were facilitated by patient advisers or participating providers to ensure that only subjects with a diagnosis of MS were included. Alpha-testers were identified through the patient panel; beta-testers were referred from patients or participating providers.

Data Collection

Potential participants were emailed invitations to review and evaluate MS-SUPPORT between October 1, 2017, and May 1, 2018. Invitations included a web link to a secure website that directed the participant though the eligibility screener, informed consent document, and baseline questionnaire. Questions assessed sociodemographics, current and previous DMT use, adherence, and self-reported knowledge about MS and treatment options. For beta-testers, we also asked for the date of their upcoming provider appointment and provider name. Eligible participants were emailed a unique, nontransferable link to the MS-SUPPORT tool that included evaluation questions. Beta testing subjects were emailed a second evaluation on the day of their scheduled provider appointment. Participants received an incentive payment ($25 online gift card) after each completed evaluation.

Assessments

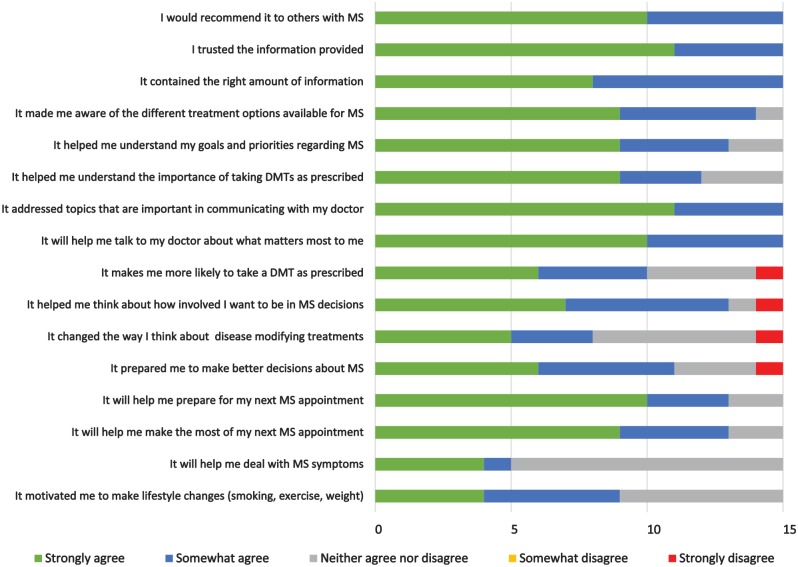

Alpha testing included online evaluation and structured video-conference interviews. Assessments addressed overall evaluation (“I would recommend it to others with MS”), usability (“It was easy to use,”“It was easy to read,”“It was well organized,”“It kept my interest,”“It contained the right amount of information”), trust in the information (“I trusted the information provided,”“It presented unbiased information”),51 patient-provider communication (“It addressed topics that are important in communicating with my doctor”), values clarification (“It helped me understand the things that matter most to me about my MS), knowledge (“It helped me understand my treatment options”), adherence (“I helped me understand the importance of taking DMTs as prescribed,”“It makes me more likely to take my medications as prescribed”), and suggestions for improvement.

Beta testing additionally evaluated the use of the tool in the context of a clinical visit with an MS provider. Beta-testing questions also addressed preparedness for the clinical visit (e.g., “It will help me make the most of my next MS doctor’s visit”), decision making (“It prepared me to make better decisions about MS”), communication (“It will help me talk to my doctor about what matters most to me”), stage of decision making,52 preparation (It will help me prepare for my next MS appointment”), and role preferences (“It helped me think about how involved I want to be in MS decisions” and the validated role preference scale46). Survey response options used a 5-point Likert-type scale (“strongly disagree,”“somewhat disagree,”“neither agree nor disagree,”“somewhat agree,”“strongly agree”). After their provider appointment, we assessed SDM-relevant items from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Clinician and Group Survey53 for Merit-based Incentive Payment System and their experience sharing their summary with their provider. Questions addressed their provider’s interest in reviewing the summary, whether the summary helped them talk to their provider about their preferences, challenges encountered, and whether MS-SUPPORT affected the quality of the visit, decision making, and motivation to make lifestyle changes. Likert response categories were “not at all,”“very little,”“somewhat,”“a lot,” or “a great deal.”

Participating providers were emailed a brief online survey just after interacting with a patient participant. An incentive payment of $50 was offered for each completed provider survey. We asked providers questions about patient-provider communication, the usefulness of the patient summary, and the patient’s preparation for the visit.

Results

Alpha testing included 14 patients with MS, of whom 11 completed the online evaluation and 9 participated in a video-conference interview (Appendix 1). A separate sample of 40 patients were invited to participate in beta testing (Appendix 1), of whom 15 completed the screening process and evaluations (Appendix 2). Those who did not complete the screening process were slightly younger and more likely to be white, male, and less educated than participants.

Alpha Testing

We iteratively revised the tool’s content, design, and tailoring algorithms during alpha testing until all identified problems were addressed and satisfactory usability ratings were obtained. This process resulted in shortening passages, removing inessential or repetitive elements, correcting programming errors, introducing skip patterns, tiering information, offering less important information as optional drill-downs, and emailing information of interest to the user upon completion. Findings are shown in Appendix 3. Because MS-SUPPORT underwent substantial revisions during alpha testing, we focus on beta testing finding.

Beta Testing

It took patients an average of 62 minutes (adjusting for outliers; range 18-496) to complete the tool. Twenty-five percent completed the tool within 36 minutes, including the evaluation module and any breaks the patient may have taken. All15 patient beta-testers wanted to share their summary with their provider, but only 8 did (7 brought a printed copy [3 out of 8 patients requested that the printout be mailed to them due to challenges printing it themselves.], 1 used their smartphone; 2 reported verbalizing the summary to their provider after forgetting to bring the report with them). Many logistical problems reported by patients were due to a single programming error that prevented patients from sharing their summary with their provider and which was corrected during beta testing. All who shared their summary reported that they (not their provider) initiated discussion about the summary. All patients agreed or strongly agreed that the report was easy to share, that they felt comfortable sharing it, and that their provider seemed interested in reviewing their report during the visit. Most of their providers asked them questions about the report. Six of seven patients agreed or strongly agreed that “the summary report helped me talk to my provider about my preferences” (the remainder neither agreed nor disagreed).

Patient evaluations after viewing MS-SUPPORT (before the clinic visit) were favorable (Figure 5). Higher ratings were reported on topics that were applicable to everyone (e.g., trust in the information, preparing for appointments, communication) as compared to topics that were more relevant to those with specific issues (e.g., severe symptoms) or behaviors (e.g., nonadherence). “Not applicable” was not a response option and all participants received the same evaluation questions. MS-SUPPORT improved 6 of 15 participants’ stage of decision making (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Patient evaluation of MS-SUPPORT before provider appointment (n = 15).

Figure 6.

Each line represents one patient participant’s stage of decision making before (blue bubbles) and after (green bubbles) viewing MS-SUPPORT.

Patient evaluations after the clinic visit suggested that the tool helped most patients with decision making, communication, and preparation (Appendix 4). Patients who shared their summary (compared to those who did not) reported higher evaluations of their providers and higher CAHPS metrics (Appendix 5).

Provider Evaluations

Fourteen patient participants were associated with 12 different providers. Four of these providers (all neurologists) completed six evaluations of MS-SUPPORT (one provider saw three participating patients). Four of these evaluations reflected visits where the patient shared their personal summary. Providers reported that it took an average of 5.25 minutes (range 1-10 minutes) to review the summary. All providers would recommend MS-SUPPORT to a colleague. Most reported that MS-SUPPORT improved the quality of care provided, the efficiency of the visit, and their knowledge of and interaction with the patient (Appendix 6). Evaluations were more positive for the four encounters in which patients shared versus did not share their personal summary.

Discussion

The patient-centered design process described succeeded in guiding the design and delivery of a feasible and potentially effective SDM tool for MS. Having patients with MS guide all stages of development added substantial complexity to the design process but increased the tool’s patient-centeredness. The development process adhered to SDM guidelines and included recommended alpha testing with patients and beta testing in “real-life” conditions.23 Additional design processes and theoretical frameworks were needed to address challenges that were not readily addressed by SDM guidelines. Image theory was instrumental in structuring information. Despite the large amount of information and options included in the tool, all testers felt MS-SUPPORT contained the right amount of information. The pilot alpha and beta testing included in the development process was instrumental in developing the intervention and guiding subject recruitment, intervention delivery, and sample size calculations for future studies and dissemination. Pilot testing that encompasses recruitment and delivery strategies has been called for in other areas54 and is especially valuable for SDM tools, where dissemination challenges persist.

Disseminating the tool to patients through patient-referral networks was feasible, required no effort by providers, and helped deliver the tool to patients who lack MS specialty care. However, delivering MS-SUPPORT to patients just in time to prepare for a clinical appointment was challenging. Providing the tool too early resulted in patients forgetting to bring their summary with them to the appointment while providing it too late did not give patients enough time to review MS-SUPPORT. Timely reminders might help overcome these challenges.

An unexpected finding was that all patients wanted to share their personal summary with their provider and all who did reported it was easy to share. However, implementation challenges were encountered. Despite offering several options for sharing the report, most patients relied on manual printing instead of the patient portal, even though the latter facilitated delivery via the electronic health records (EHRs). Participants lacked familiarity with utilizing patient portals in this manner (portals are typically used to view laboratory results or schedule appointments). Sending reminders before the HCP visit and helping patients access and use their patient portal should help. Embedding the tool directly into an EHR should obviate many logistical problems encountered, making it possible to trigger access to the tool prior to upcoming appointments and incorporate the summary page into the patient’s EHR, but was beyond the scope of this project.

We designed MS-SUPPORT to improve adherence by targeting factors that contribute to nonadherence. These factors include poor patient-provider communication, patient attitudes and beliefs about health and illness (e.g., difficulty perceiving the benefits of DMTs on infrequently occurring relapses or disability progression), high treatment costs and provider co-pays, limited access to MS specialists and specialized treatment centers, and restricted formularies.35 The self-assessments and patient feedback were intended to motivate patients to learn ways to surmount adherence obstacles. Informing providers about their patient’s adherence behaviors through the summary page may help providers address patient’s adherence challenges (many DMT nonadherent patients do not tell their provider)55 and help them select DMTs to which patients can more easily adhere. MS-SUPPORT helped people understand the importance of adherence and improved adherence expectations, which is strongly associated with actual adherence.56 However, actual adherence was not assessed.

This study builds upon a growing body of educational tools for MS. These include a decision aid for managing MS relapse,57,58 a booklet for women with MS considering motherhood,59 an information aid for newly diagnosed patients,60 a DMT booklet,58,61 and an interactive tool that compares DMTs.62 MS-SUPPORT offers the additional functionality of connecting patients to their providers to improve patient—provider communication, SDM, and adherence to treatment.

By helping patients understand their own goals and values and share them with their provider, MS-SUPPORT may help providers comply with the American Academy of Neurology’s recommendation that providers assess patient preferences for DMTs.2 Combining preference assessment with the other key elements of SDM should enhance the effectiveness of this recommendation in improving care.63 The other SDM elements include the following: 1) informing patients when they need to be involved in making a decision; 2) explaining why their preferences matter; 3) assessing patients’ desired level of involvement in decision making; 4) helping interested patients be more involved in decision making; and 5) assuring patients of their provider’s support for their decision. SDM tools such as MS-SUPPORT can help with most of these elements, but only providers can demonstrate their support for patients to participate in SDM. Providers thus play an important role in either encouraging or impeding patient involvement.64 Training providers in SDM and providing SDM tools that can be used in clinical practice should help providers create opportunities for patients to discuss their needs and preferences and engage in partnership building.44

Our pilot testing has many limitations that diminish internal and external validity, notably small sample size and lack of a control group. We relied on self-report, which may have led to a tendency for more favorable responses. Including only patients with an upcoming appointment may have resulted in selecting patients with more active disease. Many participants were relatively well-educated, though less-educated people and people with lower health literacy were included. Lower educational levels may prevent understanding of health information and compromise participation in SDM,65 but does not necessarily predict response to tools designed to overcome literacy barriers.66 We did not confirm a diagnosis of MS but our referral sources made incorrect diagnoses unlikely. Participating providers likely represented higher performing providers who were willing to engage in SDM, which could bias their responses. Our pilot testing was not designed to establish the impact of the tool but rather to improve the tool and guide future evaluation in a larger and more diverse sample.

The positive response from both patients and health care providers to the tool during beta testing establishes the feasibility of the SDM intervention and procedures for dissemination and clinical integration in real-life conditions. The process of developing the MS-SUPPORT tool can be applied to developing decision tools for other health conditions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_1_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_2_online_supp_ for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_3_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_4_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_5a_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_5b_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_5c_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_5_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_6_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Nananda Col has received consulting fees and research contracts from various entities through her contract research organization, Five Islands Consulting, LLC, also known as Shared Decision Making Resources.

Her paid and unpaid research and consulting have included developing and/or evaluating shared decision-making tools for multiple sclerosis (MS), atrial fibrillation, chronic pain, knee replacement, sleep apnea, breast cancer, coronary artery disease, carotid artery stenosis, end-stage renal disease, Crohns, fibroids, hip osteoarthritis, diabetes, menopause, peripheral vascular disease, and neurocritical care. Paid consulting included advising Biogen through their MS Quality Steering Committee, EMD-Serono in shared decision-making training for health care providers, Emmi Solutions in developing decision aids, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC (shared decision-making training, research methods training, developing and testing decision aids), Brookings Institute (travel reimbursement for advising on REMS), FDA (travel reimbursement, risk communication, and advisory committee meetings), 3D Communications (consulting), Epi-Q (consulting), Synchrony Group (consulting), Mallinckrodt’s SpecGx LLC (one-time consulting fee and reimbursement of travel), AceRx (one-time consulting fee and reimbursement of travel), Pacific Northwest University (travel expenses and honoraria), and EMD-Serono (travel expenses and speaker fees). She serves as an unpaid mentor for two NIH training (K) grants developing decision tools in the areas of sleep apnea and neurocritical care.

She received independent research grants from the nonprofit MSAA (Multiple Sclerosis Association of America), EMD-Serono (in the area of MS), Pfizer (in the area of chronic pain), and Biogen (in the area of MS). She has a research grant funded by Edwards Lifesciences (for aortic stenosis). Dr. Ionete has received consulting fees and research support from Genzyme and Biogen. Dr. Solomon has received consulting fees and research funding from Biogen, EMD Serono, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. Enrique Alvarez has received research funding from Acorda, Biogen, Novartis, and the Rocky Mountain MS Center; and consulting fees from Actelion, Biogen, Celgene, Genentech, Genzyme, Teva, Novartis, and TG Therapeutics. Ms. Patel and Dr. Livingston were employees of Biogen and are now employees of EMD-Serono. Dr. Pbert, Dr. Kutz, Dr. Ngo, Dr. Solomon, Ms. Tierman, Ms. Springmann, and Ms. Griffin have served as professional consultants to Five Islands Consulting LLC.

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided by Biogen via a contract with Shared Decision Making Resources. The external authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report was explicitly granted by the funding agreement.

The following authors were formerly employed by the sponsor: Michelle Patel, Terrie Livingston, PharmD. Biogen reviewed an earlier version of the manuscript and provided feedback to the authors. All authors approved the final content.

ORCID iD: Nananda Col  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7106-662X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7106-662X

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material for this article is available on the Medical Decision Making Policy & Practice website at https://journals.sagepub.com/home/mpp.

Contributor Information

Nananda Col, Shared Decision Making Resources, Georgetown, Maine.

Enrique Alvarez, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado.

Vicky Springmann, Shared Decision Making Resources, Georgetown, Maine.

Carolina Ionete, University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care, Worchester, Massachusetts.

Idanis Berrios Morales, University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care, Worchester, Massachusetts.

Andrew Solomon, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont.

Christen Kutz, Colorado Springs Neurological Associates, Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Carolyn Griffin, Shared Decision Making Resources, Georgetown, Maine.

Brenda Tierman, Shared Decision Making Resources, Georgetown, Maine.

Terrie Livingston, EMD Serono, Rockland, Massachusetts.

Michelle Patel, EMD Serono, Rockland, Massachusetts.

Danny van Leeuwen, Shared Decision Making Resources, Georgetown, Maine.

Long Ngo, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

Lori Pbert, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worchester, Massachusetts.

References

- 1. Matthew WB, Compson A, Allen IV, Martyn CN. McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP, Jr, et al. Disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Neurology. 2002;58(2):169–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G, D’Amico R, Filippini G. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD011381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tugwell P, Knottnerus JA. Can patient decision aids be used to improve not only decisional comfort but also adherence? J Clin Epidemiol. 2016:77:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montalbán X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peters E, Dieckmann N, Dixon A, Hibbard JH, Mertz CK. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(2):169–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carroll S, Embuldeniya G, Pannag J, Lewis K, McGillion M, Stacey D. The challenge of values-elicitation: understanding how patients’ values guide decision-making in the context of implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(10):S313. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Col NF, Solomon AJ, Springmann V, et al. Whose preferences matter? A patient-centered approach for eliciting treatment goals. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1):44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luce MF. Choosing to avoid: coping with negatively emotion-laden consumer decisions. J Consumer Res. 1998;24(4):409–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Redelmeier DA, Shafir E. Medical decision making in situations that offer multiple alternatives. JAMA. 1995;273(4):302–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520280048038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee CN, Hultman CS, Sepucha K. Do patients and providers agree about the most important facts and goals for breast reconstruction decisions? Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):563–6. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c01279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, et al. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323(7323):1218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jecker NS. The role of intimate others in medical decision making. Gerontologist. 1990;30(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hornberger JC, Habraken H, Bloch DA. Minimum data needed on patient preferences for accurate, efficient medical decision making. Med Care. 1995;33(3):297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Witteman HO, Scherer LD, Gavaruzzi T, et al. Design features of explicit values clarification methods: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(4):453–71. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15626397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marshall D, Bridges JF, Hauber B. Conjoint analysis application in health—how are studies being designed and reported? An update on current practice in the published literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient. 2010;3:249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. IPDAS 2005: Criteria for Judging the Quality of Patient Decision Aids. IPDAS Patient Decision Aid Checklist for Users. Available from: http://ipdas.ohri.ca/IPDAS_checklist.pdf

- 20. Köpke S, Solaris A, Khan F, Heesen C, Giodano. A. Information provision for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD008757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abhyankar P, Volk RJ, Blumenthal-Barby J, et al. Balancing the presentation of information and options in patient decision aids: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2013;13(Suppl. 2):S6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braddock CH, 3rd, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):339–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. ; International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feldman-Stewart D, O’Brien MA, Clayman A, et al. 2012Updated Chapter B: Providing information about options. Available from: http://ipdas.ohri.ca/IPDAS-Chapter-B.pdf

- 25. Beach LR, Mitchell TR. Image theory: principles, goals, and plans in decision making. Acta Psychol. 1987;66(3):201–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beach LR, Potter RE. The pre-choice screening of options. Acta Psychol. 1992;81(2):115–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Potter RB, Beach LR. Imperfect information in pre-choice screening of options. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1994;59(2):313–29. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pieterse AH, de Vries M, Kunneman M, Stiggelbout AM, Feldman-Stewart D. Theory-informed design of values clarification methods: a cognitive psychological perspective on patient health-related decision making. Soc Sci Med. 2013;77:156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. ; GAP Study Group. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Irwin DE, Cappell KA, Davis BM, Wu Y, Grinspan A, Gandhi SK. Differences in multiple sclerosis relapse rates based on patient adherence, average daily dose, and persistence with disease-modifying therapy: observations based on real-world data. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A764. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, White LA, Friedman M, Pill MW. Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(1 Suppl. A):S24–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003;61(4):551–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Río J, Porcel J, Téllez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(3):306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thach AV, Brown CM, Herrera V, et al. Associations between treatment satisfaction, medication beliefs, and adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(6):251–9. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2017-031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trenaman L, Selva A, Desroches S, et al. A measurement framework for adherence in patient decision aid trials applied in a systematic review subanalysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;77:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ben-Zacharia A, Adamson M, Boyd A, et al. Impact of shared decision making on disease-modifying drug adherence in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(6):287–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Seze J, Borgel F, Brudan F. Patient perceptions of multiple sclerosis and its treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:263–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Col NF, Solomon AJ, Springmann V, et al. Evaluation of a novel preference assessment tool for patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(6):260–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schiffman SS, Reynolds ML, Young FW. Introduction to Multidimensional Scaling: Theory, Methods, and Applications. West Yorkshire: Emerald Group; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fitzgerald LF, Hubert LJ. Multidimensional scaling: some possibilities for counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol. 1987;34(4):469–80. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kruskal JB, Wish M. Multidimensional Scaling. Newbury Park: Sage; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster Analysis. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fischhoff B, Brewer NT, Downs JS. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide. Silver Spring: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Street RL, Jr, Gordon HS, Ward MM, Krupat E, Kravitz RL. Patient participation in medical consultations: why some patients are more involved than others. Med Care. 2005;43(10):960–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Jr, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. Orlando: Institute for Simulation and Training, University of Central Florida; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(5):331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Katsarava Z, Ehlken B, Limmroth V, et al. ; C.A.R.E. Study Group. Adherence and cost in multiple sclerosis patients treated with IMIFN beta-1a: impact of the CARE patient management program. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler. 1996;2(5):222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kaasinen E. User acceptance of mobile services—value, ease of use, trust and ease of adoption. Available from: http://www.vtt.fi/inf/pdf/publications/2005/P566.pdf

- 52. O’Connor AM. User manual—stage of decision making. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Stage_Decision_Making.pdf

- 53. Price RA, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kistin C, Silverstein M. Pilot studies: a critical but potentially misused component of interventional research. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1561–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tintoré M, Alexander M, Costello K, et al. The state of multiple sclerosis: current insight into the patient/health care provider relationship, treatment challenges, and satisfaction. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;11:33–45. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S115090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Turner AP, Roubinov DS, Atkins DC, Haselkorn JK. Predicting medication adherence in multiple sclerosis using telephone-based home monitoring. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(1):83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kopke S, Kasper J, Mühlhauser I, Nübling M, Heesen C. Patient education program to enhance decision autonomy in multiple sclerosis relapse management: a randomized-controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2009;15(1):96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Heesen C, Kasper J, Köpke S, Richter T, Segal J, Mühlhauser I. Informed shared decision making in multiple sclerosis—inevitable or impossible? J Neurol Sci. 2007;259(1-2):109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Prunty MC, Sharpe L, Butow P, Fulcher G. The motherhood choice: a decision aid for women with multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(1):108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Solari A, Martinelli V, Trojano M, et al. ; SIMS-Trial Group. An information aid for newly-diagnosed multiple sclerosis patients improves disease knowledge and satisfaction with care. Mult Scler. 2010;16(11):1393–405. doi: 10.1177/1352458510380417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kasper J, Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Nübling M, Heesen C. Informed shared decision making about immunotherapy for patients with multiple sclerosis (ISDIMS): a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Multiple Sclerosis Trust. MS Decisions—drug comparison results. Available from: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/understanding-ms/ms-symptoms-and-treatments/ms-decisions/decision-aid/compare/443%2B451

- 63. Col NF. Patient health communication to improve shared decision making. In: Fischhoff B, Brewer NT, Downs JS, eds. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide. Bethesda: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Risk Communication Advisory Committee and consultants; 2011;173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Makoul G. Perpetuating passivity: reliance and reciprocal determinism in physician-patient interaction. J Health Commun. 1998;3(3):233–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Moccia M, Carotenuto A, Massarelli M, Lanzillo R, Morra VB. Can people with multiple sclerosis actually understand what they read in the Internet age? J Clin Neurosci. 2016;25:167–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Col NF, Fortin J, Ngo L, O’Connor AM, Goldberg RG. Can computerized decision support help patients make complex treatment decisions? A randomized controlled trial of an individualized menopause decision aid. Med Decis Making. 2007;27(5):585–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix_1_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_2_online_supp_ for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_3_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_4_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_5a_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_5b_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_5c_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_5_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice

Supplemental material, Appendix_6_online_supp for A Novel Tool to Improve Shared Decision Making and Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis: Development and Preliminary Testing by Nananda Col, Enrique Alvarez, Vicky Springmann, Carolina Ionete, Idanis Berrios Morales, Andrew Solomon, Christen Kutz, Carolyn Griffin, Brenda Tierman, Terrie Livingston, Michelle Patel, Danny van Leeuwen, Long Ngo and Lori Pbert in MDM Policy & Practice