Abstract

Chiari Malformation Type 1 is a congenital, condition characterized by abnormally shaped cerebellar tonsils that are displaced below the level of the foramen magnum.

NKX2-1 gene encodes a transcription factor expressed during early development of thyroid, lung, and forebrain, and germline NKX2-1 mutations can lead to dysfunction in any of these three organs, resulting in brain–lung–thyroid syndrome. There have been few reports of structural brain anomalies in patients with an NKX2-1-related disorder. We report the first case of a girl with a genetically identified mutation in NKX2-1 that presents with a Chiari Malformation Type 1, eventually expanding the phenotypic spectrum of NKX2-1-related disorders while also highlighting a novel heterozygous pathogenic variant at exon 3 that disrupts the reading framework, originating an NKX2-1 protein with a different C-terminal.

Keywords: Brain, Chiari, choreoathetosis, hypothyroidism, NKX2-1

Introduction

Chiari Malformation Type 1 (CM1), first described by Hans Chiari in 1891,[1] is a congenital condition characterized by abnormally shaped cerebellar tonsils that are displaced below the level of the foramen magnum.[2]

In the last decades, with the advent of neuroimaging, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) the diagnosis of CM1 has been on the rise, with an estimated prevalence of 1% in the pediatric population.[3]

The pathogenesis of CM1 is heterogeneous, but always involves a discrepancy between content “forebrain and hindbrain” and container “supratentorial cranial vault, posterior fossa” with or without associated abnormalities of the craniocervical junction.[3]

NKX2-1 gene is a member of the homeodomain-containing NK-2 gene family and encodes a transcription factor expressed during early development of thyroid, lung, and forebrain, particularly the basal ganglia and hypothalamus.[4] Germline mutations of NKX2-1 can lead to dysfunction in any of these three organs[5] and the resulting disorder is known as choreoathetosis and congenital hypothyroidism with or without pulmonary dysfunction, or brain–lung–thyroid syndrome.[6] Roughly half of affected patients have the complete triad of brain, lung, and thyroid symptoms but the phenotype is variable both between and within families.[6] Central nervous system involvement (hypotonia and chorea) is a classic early finding in NKX2-1-related disorders, but structural brain abnormalities were rarely identified.[7]

We report the first case of a girl with a genetically identified mutation in NKX2-1 with a CM1.

Case report

We report a female patient, born at full term (39 weeks) by vaginal delivery, following an uneventful pregnancy. She was born in good condition with a birth weight of 2750g and Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at 1min and 5min, respectively. Metabolic newborn panel was positive for a congenital hypothyroidism (TSH level of 110.9 mIU/L) and levothyroxine was started at a dose of 25 mcg on eighth postnatal day. Cervical ultrasonography revealed a thyroid gland without any focal lesions but with a size in the lower limit of normal. She is the first child of healthy non-consanguineous parents, and her family history is unremarkable in the enlarged families of both parents.

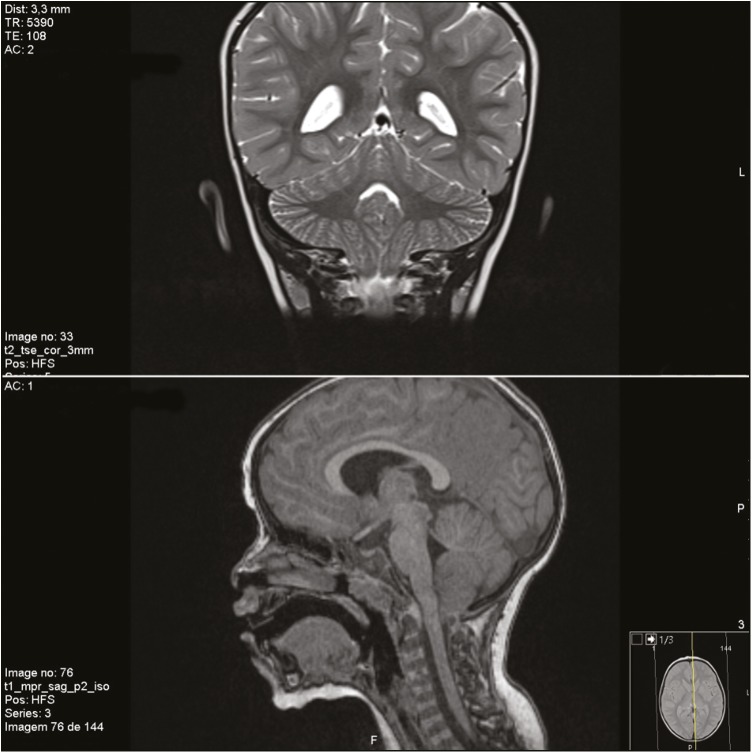

She was referred to a tertiary care hospital at 24 months with a diagnosis of hypotonia and gross motor delay. Motor milestones were achieved late (she could sit independently at 15 months and was not able to walk independently at the current observation). She had no dysmorphic features on physical examination and on neurological examination she had truncal and gait ataxia, with dysmetria and normal eye movements. A metabolic panel was ordered, along with an electromyogram (EMG) and a brain MRI. Both metabolic panel and EMG were normal, and brain MRI revealed a CM1 [Figure 1], with cerebellar tonsils placed 10 mm below the foramen magnum, without associated anomalies of the cranio-cervical junction. A next-generation sequencing panel for hereditary ataxias was ordered and ultimately revealed normal. She was able to walk independently at 26 months and at a subsequent review at the age of three years old she presented with choreoathetosis of the upper limbs, which led to a presumptive diagnosis of an NKX2-1-related disorder. Polymerase chain reaction sequencing of NKX2-1 gene revealed a heterozygous pathogenic variant, c.859_860insTGCC (p.Arg287Leufs*?) –– exon 3, which has not been described before, that disrupts the reading framework, originating an NKX2-1 protein with a different C-terminal. Tetrabenazine was started and chorea improved. Nowadays, at six years old, her cognitive profile is characterized mainly by a speech sound disorder (articulatory), with normal expressive and receptive language skills, and also by a motor coordination disorder (both gross and fine motor and handwriting skills). She has a slight coreoathetosis of upper limbs and cerebellar ataxia with dysarthria, dysmetria, and unsteady gait. She requires ongoing educational support and rehabilitation. Her IQ is in the low-normal range for her age. Although she has no signs or symptoms of pulmonary disease so far, she was evaluated in Pneumology Clinic and has a normal chest X-ray and normal pulmonary function tests.

Figure 1.

Chiari Malformation Type 1 in our patient

Discussion

Some rarely identified structural brain anomalies in patients with an NKX2-1-related disorder have been reported, including abnormal sella turcica,[8] agenesis of the corpus callosum,[9] cavum septum pellucidum with microcephaly,[10] hypoplastic pallidum,[11] and pituitary cysts.[12] To the best of our knowledge, we describe the first patient with an association of a CMT1 malformation and an NKX2-1-related disorder, expanding the (already wide) spectrum of manifestations of NKX2-1-related disorders.

Homeobox genes, such as NKX2-1, are genes that direct the formation of many body structures during early embryonic development. In the course of brain development, NKX2-1 expression is found in both telencephalic and diencephalic domains[13] and is involved in interneuron specification and migration. Lack of functional NKX2-1 protein in neurons impairs developmental differentiation and organization of basal ganglia and basal forebrain.[14] To date, there are reports of multiple interactions between NKX2-1 and other genes.[15] We hypothesize that NKX2-1 may interact with other genes responsible for cerebellar migration, skull bone abnormalities, or any other factors resulting in overcrowding in the posterior fossa, resulting in a CMT1.

We also highlight a novel NKX2-1 mutation c.859_860insTGCC (p.Arg287Leufs*?) that has never been reported before, but is located on a mutational hot-spot at exon 3, with six mutations affecting this site previously been reported[12] and affects the C-terminal activation domain. The distribution of point mutations in the NKX2-1 gene causing NKX2-1-related disorders is uneven,[12] which ultimately leads to different clinical phenotypes.

The absence of pulmonary involvement is not unexpected, as approximately 50% of patients do not have pulmonary symptoms.[16] Although the highest risk for occurrence of pulmonary manifestations is in the first decade of life, there have been reports of pulmonary fibrosis occurring in older individuals,[17] and thus an annual evaluation including pulmonary function tests is recommended.

Cognitive status in patients with an NKX2-1-related disorder has historically been considered normal,[18] although congenital hypothyroidism, if untreated, could lead to an intellectual developmental disorder. However, despite a normal cognitive profile, dysgraphia due to the choreic movements and the speech sound disorder both require continuous educational support and rehabilitation both with speech and occupational therapy. Furthermore, the chorea itself may predispose to social embarrassment and isolation.

Conclusion

In summary, we highlight a further case of an NKX2-1-related disorder with a novel mutation on exon 3 and expand the spectrum of structural brain abnormalities in these disorders to include a CM1. Further genetical investigation might elucidate an underlying pathogenic interaction between the NKX2-1 homeobox gene and posterior fossa overcrowding. A high index of suspicion should be maintained in patients with either congenital hypothyroidism or pulmonary disease with motor developmental delay that progresses to a movement disorder. As the awareness of the phenotypic variability of NKX2-1-related disorders is increasing, more cases will likely be diagnosed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chiari H. Über Veränderungen des Kleinhirns, des Pons und derMedulla oblongata infolge von congenitaler Hydrocephalie des Grosshirns. Denkschr der Kais Akad Wiss Wien mathnaturw. 1896;63:71–116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarnat HB. Disorders of segmentation of the neural tube: Chiari Malformations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;87:89–103. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)87006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aitken LA, Lindan CE, Sidney S, Gupta N, Barkovich AJ, Sorel M, et al. Chiari Type I Malformation in a pediatric population. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40:449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.do Carmo Costa M, Costa C, Silva AP, Evangelista P, Santos L, Ferro A, et al. Nonsense mutation in TITF1 in a Portuguese family with benign hereditary chorea. Neurogenetics. 2005;6:209–15. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorwath A, Schnittert-Hübener S, Schrumpf P, Müller I, Jyrch S, Dame C, et al. Comprehensive genotyping and clinical characterisation reveal 27 novel NKX2-1 mutations and expand the phenotypic spectrum. J Med Genet. 2014;51:375–87. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel NJ, Jankovic J. NKX2-1-related Disorders. 2014 Feb 20 [Updated 2016 Jul 29] In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veneziano L, Parkinson MH, Mantuano E, Frontali M, Bhatia KP, Giunti P. A novel de novo mutation of the TITF1/NKX2-1 gene causing ataxia, benign hereditary chorea, hypothyroidism and a pituitary mass in a UK family and review of the literature. Cerebellum. 2014;13:588–95. doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0570-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krude H, Schütz B, Biebermann H, von Moers A, Schnabel D, Neitzel H, et al. Choreoathetosis, hypothyroidism, and pulmonary alterations due to human NKX2-1 haploinsufficiency. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:475–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI14341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carré A, Szinnai G, Castanet M, Sura-Trueba S, Tron E, Broutin-L’Hermite I, et al. Five new TTF1/NKX2.1 mutations in brain-lung-thyroid syndrome: rescue by PAX8 synergism in one case. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2266–76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwatani N, Mabe H, Devriendt K, Kodama M, Miike T. Deletion of NKX2.1 gene encoding thyroid transcription factor-1 in two siblings with hypothyroidism and respiratory failure. J Pediatr. 2000;137:272–6. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleiner-Fisman G, Lang AE. Benign hereditary chorea revisited: a journey to understanding. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2297–305. doi: 10.1002/mds.21644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veneziano L, Parkinson MH, Mantuano E, Frontali M, Bhatia KP, Giunti P. A novel de novo mutation of the TITF1/NKX2-1 gene causing ataxia, benign hereditary chorea, hypothyroidism and a pituitary mass in a UK family and review of the literature. Cerebellum. 2014;13:588–95. doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0570-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleiner-Fisman G, Calingasan NY, Putt M, Chen J, Beal MF, Lang AE. Alterations of striatal neurons in benign hereditary chorea. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1353–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nóbrega-Pereira S, Kessaris N, Du T, Kimura S, Anderson SA, Marín O. Postmitotic nkx2-1 controls the migration of telencephalic interneurons by direct repression of guidance receptors. Neuron. 2008;59:733–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NK2 Homeobox 1 [Homo sapiens (human)] [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/7080 .

- 16.Gras D, Jonard L, Roze E, Chantot-Bastaraud S, Koht J, Motte J, et al. Benign hereditary chorea: phenotype, prognosis, therapeutic outcome and long term follow-up in a large series with new mutations in the TITF1/NKX2-1 gene. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:956–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamvas A, Deterding RR, Wert SE, White FV, Dishop MK, Alfano DN, et al. Heterogeneous pulmonary phenotypes associated with mutations in the thyroid transcription factor gene NKX2-1. Chest. 2013;144:794–804. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peall KJ, Kurian MA. Benign hereditary chorea: an update. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2015;5:314. doi: 10.7916/D8RJ4HM5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]