Abstract

Nipah virus (NiV) is a highly lethal zoonotic paramyxovirus that emerged at the end of last century as a human pathogen capable of causing severe acute respiratory infection and encephalitis. Although NiV provokes serious diseases in numerous mammalian species, the infection seems to be asymptomatic in NiV natural hosts, the fruit bats, which provide a continuous virus source for further outbreaks. Consecutive human-to-human transmission has been frequently observed during outbreaks in Bangladesh and India. NiV was shown to interfere with the innate immune response and interferon type I signaling, restraining the anti-viral response and permitting viral spread. Studies of adaptive immunity in infected patients and animal models have suggested an unbalanced immune response during NiV infection. Here, we summarize some of the recent studies of NiV pathogenesis and NiV-induced modulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses, as well as the development of novel prophylactic and therapeutic approaches, necessary to control this highly lethal emerging infection.

Keywords: Nipah virus, innate immunity, adaptive immunity, pathogenesis, animal models, contra-measures

Introduction

Emerging infectious diseases pose a significant threat to human and animal welfare in the world. Nipah virus (NiV) is a recently emerged zoonotic Paramyxovirus, from the Mononegavirales order, capable of causing considerable morbidity and mortality in numerous mammalian species, including humans 1– 3. Although NiV infection remains rare in humans, this virus has captured the attention of both scientific and public health communities because of its high fatality rate, ranging from 40% in Malaysia to more than 90% in Bangladesh and India, where it was associated with frequent person-to-person transmission 4, 5. Having the capacity to cause severe zoonosis with serious health and economic problems, without efficient treatment yet available, NiV is considered a possible agent for bioterrorism 6, has global pandemic potential 7, and is classified as a biosecurity level 4 (BSL4) pathogen. In 2015, the World Health Organization included NiV in the Blueprint list of eight priority pathogens for research and development in a public health emergency context 8. Furthermore, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations has targeted NiV as a priority for vaccine development on the basis of its high potential to cause severe outbreaks 9.

Viral structure and epidemiology

NiV belongs to Henipavirus genus, along with the highly pathogenic Hendra virus (HeV), which emerged in Australia in 1994 10, and the non-pathogenic Cedar virus discovered in 2012 11. Moreover, Henipa-like full-length viral sequences were found in African fruit bats 12 and Chinese rats (Moijang virus) 13. Two major genotypes of NiV have been identified so far: Malaysia and Bangladesh, which share 92% of nucleotide homology 14, 15 and present some differences in their pathogenicity 16. The NiV genome is composed of a negative-sense, single, non-segmented RNA and contains six transcription units encoding for six viral structural proteins (3′-N-P-M-F-G-L-5′) and three predicted P gene products coding for non-structural proteins, C, V, and W, demonstrated to function as inhibitors of the host innate immune response 17– 20.

NiV was first identified as the cause of an outbreak of encephalitis in humans during 1998 to 1999 in Malaysia and Singapore 21. The virus has been transmitted from infected pigs to humans, and the control of the epidemic necessitated culling over 1 million pigs, presenting a huge economic burden 22, 23. Although no further outbreaks have occurred in Malaysia since then, annual outbreaks of the new NiV strain have started since 2001 in Bangladesh 5. The new NiV cases have been identified in the other parts of Southeast Asia: one in Philippines 24 and three in India, with the last one in the state of Kerala, reaching a fatality rate of 91% 4, solidifying NiV as a persistent and serious threat in South Asia.

Fruit bats from Pteropus species (flying foxes) have been recognized as the natural host of NiV 25. Deforestation in large regions of Southeast Asia damages bat roosting trees and food supplies, leading to the migration of bat colonies toward urban sites, thus increasing the contact with humans 26, 27. NiV transmission from bats to humans was shown to occur through consumption of raw date palm juice or fruits contaminated with bat saliva or urine 28. Alternatively, transmission occurs via close contact with infected domestic animals acting as viral amplifying vectors, such as pigs or horses, and via inter-human transmission in one third of NiV Bangladesh strain infections 5, 29, 30. In addition, NiV and Henipa-like viruses have been molecularly or serologically detected (or both) in Pteropus bats in different countries from Asia and Africa 12, and the worldwide distribution of these bat species poses a threat to potential NiV pandemics 7.

Nipah virus pathogenesis and animal models

NiV-caused disease is characterized by the onset of non-specific symptoms, including fever, headache, dizziness, vomiting, and myalgia. Later, patients may develop severe encephalitis and pulmonary disease. Respiratory syndrome is observed more frequently in patients infected with NiV Bangladesh. Recently, the persistence of NiV RNA was described in the semen of a patient surviving NiV infection in India 31; this is similar to what has been previously reported for Ebola 32 and Zika 33 virus. Survivors from NiV infection frequently have long-term neurological sequelae 34. Furthermore, another clinical syndrome, late-onset encephalitis, has been observed in some patients following an initial NiV infection that was either mild or asymptomatic. Finally, relapse encephalitis could develop as resurgences of the virus, appearing several months to years after recovering from a symptomatic initial infection 35, including a case in which encephalitis occurred 11 years after initial infection 36.

Primary human epithelial cells from the respiratory tract were shown to be highly permissive to Henipaviruses and may represent the initial site of infection 37. Additionally, the virus shows a high neuro-tropism and the ability to infect muscular cells, suggesting rather ubiquitous expression of its entry receptors in different tissues 2. In contrast to some other Paramyxoviridae, NiV is not lymphotropic, and among different blood cell types, NiV could infect dendritic cells only 38. Nevertheless, viral dissemination within the host is facilitated by NiV attachment to circulating leukocytes through binding to heparan sulfate without infecting the cells 39, using leukocytes as a cargo allowing viral transfer to endothelial vascular cells through a mechanism of transinfection 38.

NiV uses Ephrin-B2 and -B3 as entry receptors that are highly conserved among numerous species 40– 43. Indeed, various mammalian species such as hamsters, ferrets, cats and bigger animals, including horses, pigs, and non-human primates, have been experimentally infected and used to develop potential new therapeutics 44, 45. Furthermore, Pteropus fruit bats, the natural reservoir of the virus, were experimentally inoculated with NiV in order to study their susceptibility to infection, viral distribution, and pathogenesis 46, 47. No clinical signs were observed in flying foxes, raising the interest of the scientific community in the study of fruit bat–NiV interactions and understanding their capacity to control NiV infection 47– 49.

Infection of hamsters with both NiV or HeV induces acute fatal encephalitis with a pathology similar to that of humans 50, 51 and this small-animal model provides a useful tool in studying both pathogenesis and potential countermeasures. As pigs were the critical amplifying host during the NiV outbreak in Malaysia, they have also been used as a model for NiV infection. Indeed, viral shedding, associated with an invasion of the central nervous system, has been associated with a mortality of 10 to 15% in infected animals 52. Interestingly, unlike other species, NiV is able to infect certain populations of swine lymphocytes 53. Similarly to what has been observed in hamsters 54, the NiV Malaysia strain induces higher virus replication and clinical signs in pigs, compared with the NiV Bangladesh strain 55. Remarkably, in the ferret model, the NiV Malaysia and Bangladesh strains showed similar pathogenicity 56, although higher amounts of viral RNA were recovered in oral secretions from ferrets infected with NiV Bangladesh 57.

Although mice represent a small-animal model convenient to study viral infections providing a well-developed experimental toolbox, NiV induces a subclinical infection in elderly wild-type mice only 58. However, it has been demonstrated that NiV infection is highly lethal in interferon receptor type I (IFN-I)-deficient mice 59, 60.

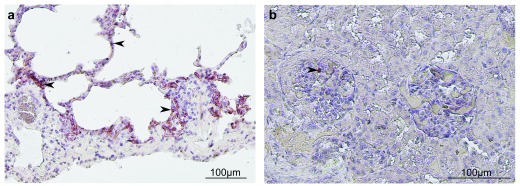

Development of non-human primate models is particularly important for the advances in anti-viral preventive and therapeutic approaches. Squirrel monkeys 61 and African green monkeys (AGMs) 62 are susceptible to NiV infection, and the AGM model has been used extensively as its general disease progression and symptomatology are similar to those of NiV-infected humans. NiV infection through the respiratory route in AGM induces a generalized vasculitis and reproduces the clinical symptoms observed in humans, including respiratory distress 62, 63, a neurological disease 64, and a viral persistence in the brain from surviving animals 65. Furthermore, concomitant to human infections, NiV Bangladesh is more pathogenic than the NiV Malaysia strain in AGM 66. Pathogenesis following NiV infection is observed mainly in the respiratory tract and is characterized by acute respiratory distress syndrome and pneumonia following infection of epithelial cells ( Figure 1a). As in other animal models, the virus could be found in a wide range of tissues, including kidneys ( Figure 1b), brain, or liver (or a combination of these), suggesting efficient viral dissemination 62, 67.

Figure 1. Immunohistochemistry of African green monkey (AGM) tissues after Nipah virus (NiV) infection.

An AGM was infected by NiV via the respiratory route, and necropsy was performed 8 days after infection. Immunostaining of lungs ( a) and kidney ( b) was made by using a polyclonal rabbit antibody specific for NiV nucleoprotein, and hematoxylin was used for the counter-staining. Interstitial pneumonia was found in lungs, inflammatory cells were present in both lungs and kidney, and positive immunostaining for NiV N (arrows) was observed in the alveolar wall and kidney glomerulus.

Innate immunity and interferon type I signaling

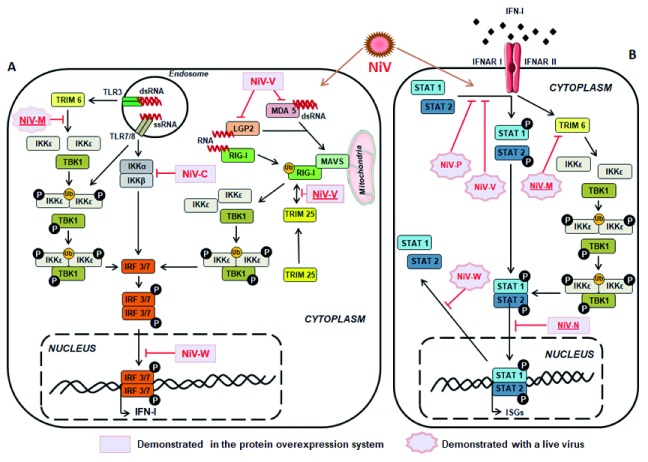

Innate immune response plays a critical role in anti-viral host defense and its modulation during NiV infection has been demonstrated in several reports 17, 68– 71. Robust expression of anti-viral genes in lung tissue, including MX1, RSAD2, ISG15, and OAS1, during the early stages of NiV infection in ferrets was not sufficient to contain viral dissemination 56. Suppression of IFN-I production is known to promote viral spread by disrupting the first lines of defense, resulting in important tissue damage and leading to death. Several mechanisms have been described and both structural and non-structural NiV proteins were found to be involved in the blocking of IFN-I signaling pathway, using distinct strategies 72– 78, as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic presentation of Nipah virus (NiV)-induced modulation of type I interferon (IFN-I) production and signaling.

( a) NiV infection is followed by the production of viral RNA, which activates TLR and RLR pathways in the cell, leading to the activation of IFN-I and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). However, several NiV proteins could interfere with this activation at different levels. NiV-V disrupts MDA5 and LGP2 stimulation and subsequent RIG-I activation 81. Conjointly, NiV-C protein counteracts IKKα/β dimerization, important for the activation of IRF3 and IRF7 82, while NiV-W protein prevents nuclear transport of phosphorylated IRF3/7 dimers 78. In addition, NiV-V protein inhibits RIG-I activation and its signaling pathway by binding to its caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) following anterior binding to TRIM25 that prevents further RIG-I ubiquitination 80. Finally, experiments using a live virus NiV deficient in M gene expression highlighted the effect of NiV-M in the degradation of TRIM6 and disruption of IKKε ubiquitination (Ub), oligomerization, and subsequent phosphorylation (P) by preventing synthesis of K48-linked unanchored polyubiquitin chains 83. ( b) NiV-induced production of IFN-I leads to the stimulation of IFN-I receptor (IFNAR) and subsequent anti-viral signaling, which could be disrupted by several NiV proteins. NiV-N could inhibit nuclear import of STAT1/2 dimer 84, while NiV-M triggers degradation of TRIM6 and disrupts subsequent IKKε, TBK1, and STAT1/2 phosphorylation 83, as described in (a). In addition, experiments using live virus demonstrated that NiV-P and V could interfere with STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation 73, 75 while NiV-W prevents their nuclear exportation 77. Those mechanisms, combined, constitute the immune evasion strategy displayed during NiV infection, allowing an efficient host invasion. Inhibitory mechanisms presented by underlined NiV proteins correspond to studies published after 2016.

Inhibition of IFN-I response was observed in different animal models during the course of NiV infection. Indeed, NiV infection of hamsters 79 and ferrets 56 provides insight into the specific viral signature with a downregulated or delayed IFN-I response during the course of infection. In addition, several in vitro studies allowed the identification of viral proteins involved in immune suppression, providing detailed mechanisms of the modulation of IFN-related pathways. Sanchez-Aparicio et al. reported interactions between non-structural NiV-V protein and both RIG-I and RIG-I regulatory protein TRIM25 80. They described the binding of the conserved C-terminal domain of NiV-V to caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs) of RIG-I and the SPRY domain of TRIM25, thus preventing ubiquitination of RIG-I and its downstream signaling ( Figure 2a). In addition to previously described antagonist effects of NiV-V on MDA5 and STAT1 activation 73, 81, this recent report highlights the multirole of NiV-V protein in dismantling the IFN-I response. Furthermore, another study described the capacity of NiV matrix protein (M), known to be important in virus assembly and budding, to disrupt IFN-I signaling ( Figure 2b). Indeed, NiV-M protein interacts with E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM6, triggering its degradation and subsequent inhibition of IKKε kinase-mediated IFN-I response 83. These results were confirmed by a reduced level of endogenous TRIM6 expression upon NiV infection only when M was expressed. Moreover, the role of NiV nucleoprotein (N) was recently reported in hampering IFN-I signaling by preventing the nuclear transport of both signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2 84, subsequently impairing the expression of IFN-stimulated genes. All together, these recently described routes used by NiV proteins to prevent host anti-viral response provide new insights into viral evasion mechanisms involved in the control of the IFN-I pathway.

Adaptive immunity

NiV causes an important modulation of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses during the course of infection 85, 86. The NiV outbreak in Kerala in May 2018 provided the opportunity to study the adaptive immune responses in two surviving patients infected with the NiV Bangladesh strain 85. Although absolute number of T-lymphocytes remained normal in blood, the marked elevation of activated CD8 T cells, co-expressing granzyme B and PD-1 was observed, suggesting the increase of lymphocyte population important for the elimination of infected cells. Patients surviving NiV infection also had elevated counts in B-lymphocytes, associated with an important generation of NiV-specific IgM and IgG antibodies. These data support the importance of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in the protection against NiV infection. Survivors from NiV infection elicited a stronger, more efficient, and more balanced immune response compared with fatalities.

Three recent studies evaluated immune responses in peripheral blood and tissues in ferrets and monkeys, following infection through the respiratory route 56, 63, 87. Analysis of the gene expression profile in ferrets following the infection with the NiV Bangladesh strain showed a time-dependent increase of macrophage markers and an unchanged level of lymphocyte markers in lungs, while brain infection was characterized by limited immune response 56, thus presenting the first global characterization of the host gene expression during Henipavirus infection. Study of the peripheral immune response in NiV-infected AGM highlighted the onset of a cell-mediated immune response through the production of Th1-associated cytokines and an increase in CD8 + T cell activation/proliferation markers in blood, lung, and brain tissues, although neutralizing antibodies were not generated during the 10-day course of infection 63. Interestingly, the study of natural killer (NK)-cell response during infection in AGM emphasized an increase in their proliferation, activation, and functional activity during both acute and convalescent phases in surviving animals contrary to succumbing ones 87, thus suggesting the implication of NK cells in anti-NiV response.

New strategies to control Nipah virus infection

Several vaccine development strategies have recently been studied in small-animal models, including chimeric rabies-based 88, virus-like particle (VLP)-based 89, adenovirus-based 90, and epitope-based 91, 92 vaccines. Those approaches induced a protection against NiV by triggering a specific response against its envelope glycoprotein G that will require further development using non-human primates to evaluate their efficiency and safety. An additional study using recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing NiV-G protein, in addition to Ebola virus GP protein (rVSV-EBOV-GP-NiV-G), demonstrated complete protection from a high dose of NiV in the hamster model 93. That study was followed by further evaluation of the vaccine vector in the AGM model, where the induction of a robust and rapid protective anti-NiV immune response was observed 94, 95. Vaccination of animals with rVSV-EBOV-GP-NiV-G vector induced protection against NiV challenge when administered either the day before or at the day of challenge and elicited partial protection when administered up to 1 day post-exposure. A plausible explanation of the mechanism involved in the generation of this fast protection could be the stimulation of the host’s innate immune response, inhibiting viral replication and allowing the development of a virus-specific adaptive immune response. Altogether, this recent work and previous reports highlight the importance of the humoral immune response and the protective role of antibodies directed against viral proteins in the control of NiV infection. Indeed, the human monoclonal antibody specific for Hendra G protein, m102.4, elicited promising results against Henipavirus infection following its passive transfer in infected ferrets 96 and AGM 97 and is being tested in clinical trials.

Although the development of potential NiV vaccines is ongoing and the scrutiny to get authorized vaccines directed against BSL4 pathogens has been accelerated, the only approved vaccine on the market is an animal vaccine directed against HeV in horses in Australia (Equivac-HeV). The importance of a cell-mediated immune protection against Henipaviruses has been demonstrated in hamsters and pigs 86, 98, 99, indicating that particular attention should be given to this arm of the immune response for the development of new vaccines. Moreover, these reports underline that both well-balanced innate and adaptive immune responses play important roles in the control of NiV infection.

In parallel to vaccines, other therapeutic strategies have been under development. Recent in vitro investigations demonstrated that nucleoside inhibitor 4′-azidocytidine (R1479) and its analogs, previously identified to inhibit flaviviruses, are also capable of inhibiting NiV replication and may present potential broad-spectrum anti-viral candidates for future development 100, 101. A recent study in hamsters demonstrated the ability of favipiravir (T-705), a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor that acts as a purine analog, in preventing NiV-induced morbidity and mortality when administered immediately following infection 102. Those results indicate that favipiravir, shown previously to protect against Ebola virus infection 103, is a potentially good candidate for post-exposure prophylaxis to NiV. A different approach has been developed by specifically inhibiting NiV entry into the cells by acting on the fusion machinery 104. Indeed, viral entry is mediated by the viral envelope glycoproteins G and F (fusion protein) and can be targeted by fusion-inhibitory peptides 2. Intra-tracheal administration of these peptides conjugated to lipids, shown to increase their efficiency, was protective in both hamsters and AGM against high-dose lethal NiV challenge. Finally, recent promising work has validated the efficiency of remdesivir (GS-5734), a broad-acting anti-viral nucleotide prodrug, against NiV Bangladesh in an AGM model, demonstrating its ability to protect monkeys if given 24 hours post-infection 105. Clinical trials of this drug against Ebola virus have recently been started in democratic republic of Congo 106 and a similar approach will be required for the evaluation of remdesivir against NiV.

Conclusions and future directions

NiV attracts particular attention among members of the Paramyxovirus family, as it possesses high zoonotic potential associated with one of the highest fatality rates observed in infectious diseases. The wide distribution of its natural host, the fruit bats, combined with the possibility of the spread of NiV via the respiratory route, raises the risk that pandemics will be caused by this virus in the future and calls for a better understanding of its pathogenesis and the development of efficient anti-viral approaches. NiV proteins were shown to effectively interact with the immune response and disable the establishment of a protective anti-viral immunity. Understanding the host–pathogen relationship at both molecular and cellular levels in different species and elucidating how bats could efficiently control NiV infection represent exciting challenges for future research and may open new avenues in the development of innovative anti-viral strategies. These studies should lead to novel clinical trials, allowing the generation of drugs efficient in the treatment of NiV infection. Further studies require a multidisciplinary approach, putting together virologists, immunologists, epidemiologists, veterinarians, and physicians within a “one health approach” in the common endeavor to understand and control Henipavirus infections.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Benhur Lee, Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Hector Aguilar-Carreno, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Vincent Munster, Laboratory of Virology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, MT, USA

Funding Statement

The work was supported by LABEX ECOFECT (ANR-11-LABX-0048) of Lyon University within the “Investissements d’Avenir” program (ANR-11-IDEX-0007) conducted by the French National Research Agency (NRA) and by the Aviesan Sino-French agreement on Nipah virus study. RP is supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Direction Générale de l’Armement (DGA).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 3 approved]

References

- 1. Marsh GA, Netter HJ: Henipavirus Infection: Natural History and the Virus-Host Interplay. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2018;10:197–216. 10.1007/s40506-018-0155-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mathieu C, Horvat B: Henipavirus pathogenesis and antiviral approaches. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(3):343–54. 10.1586/14787210.2015.1001838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh RK, Dhama K, Chakraborty S, et al. : Nipah virus: epidemiology, pathology, immunobiology and advances in diagnosis, vaccine designing and control strategies - a comprehensive review. Vet Q. 2019;39(1):26–55. 10.1080/01652176.2019.1580827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arunkumar G, Chandni R, Mourya DT, et al. : Outbreak Investigation of Nipah Virus Disease in Kerala, India, 2018. J Infect Dis. 2019;219(12):1867–1878. 10.1093/infdis/jiy612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 5. Nikolay B, Salje H, Hossain MJ, et al. : Transmission of Nipah Virus - 14 Years of Investigations in Bangladesh. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(19):1804–1814. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 6. Lam SK: Nipah virus—a potential agent of bioterrorism? Antiviral Res. 2003;57(1–2):113–9. 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00204-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luby SP: The pandemic potential of Nipah virus. Antiviral Res. 2013;100(1):38–43. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sweileh WM: Global research trends of World Health Organization’s top eight emerging pathogens. Global Health. 2017;13(1):9. 10.1186/s12992-017-0233-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plotkin SA: Vaccines for epidemic infections and the role of CEPI. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(12):2755–2762. 10.1080/21645515.2017.1306615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 10. Murray K, Selleck P, Hooper P, et al. : A morbillivirus that caused fatal disease in horses and humans. Science. 1995;268(5207):94–7. 10.1126/science.7701348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marsh GA, de Jong C, Barr JA, et al. : Cedar virus: a novel Henipavirus Isolated from Australian bats. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(8):e1002836. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drexler JF, Corman VM, Müller MA, et al. : Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun. 2012;3:796. 10.1038/ncomms1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 13. Wu Z, Yang L, Yang F, et al. : Novel Henipa-like virus, Mojiang Paramyxovirus, in rats, China, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(6):1064–6. 10.3201/eid2006.131022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harcourt BH, Lowe L, Tamin A, et al. : Genetic characterization of Nipah virus, Bangladesh, 2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(10):1594–7. 10.3201/eid1110.050513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lo MK, Lowe L, Hummel KB, et al. : Characterization of Nipah virus from outbreaks in Bangladesh, 2008-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(2):248–55. 10.3201/eid1802.111492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clayton BA, Marsh GA: Nipah viruses from Malaysia and Bangladesh: two of a kind? Future Virol. 2014;9:935–46. 10.2217/fvl.14.74 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mathieu C, Guillaume V, Volchkova VA, et al. : Nonstructural Nipah virus C protein regulates both the early host proinflammatory response and viral virulence. J Virol. 2012;86(19):10766–75. 10.1128/JVI.01203-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Satterfield BA, Cross RW, Fenton KA, et al. : The immunomodulating V and W proteins of Nipah virus determine disease course. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7483. 10.1038/ncomms8483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 19. Enchéry F, Horvat B: Recent challenges in understanding Henipavirus immunopathogenesis: role of nonstructural viral proteins. Future Virol. 2014;9:527–30. 10.2217/fvl.14.37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lo MK, Peeples ME, Bellini WJ, et al. : Distinct and overlapping roles of Nipah virus P gene products in modulating the human endothelial cell antiviral response. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47790. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, et al. : Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science. 2000;288(5470):1432–5. 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lam SK, Chua KB: Nipah virus encephalitis outbreak in Malaysia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34 Suppl 2:S48–51. 10.1086/338818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharma V, Kaushik S, Kumar R, et al. : Emerging trends of Nipah virus: A review. Rev Med Virol. 2019;29(1):e2010. 10.1002/rmv.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ching PK, de los Reyes VC, Sucaldito MN, et al. : Outbreak of henipavirus infection, Philippines, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(2):328–31. 10.3201/eid2102.141433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Fogarty R, et al. : Pteropid bats are confirmed as the reservoir hosts of henipaviruses: a comprehensive experimental study of virus transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(5):946–51. 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olival KJ, Daszak P: The ecology of emerging neurotropic viruses. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(5):441–6. 10.1080/13550280591002450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Enchéry F, Horvat B: Understanding the interaction between henipaviruses and their natural host, fruit bats: Paving the way toward control of highly lethal infection in humans. Int Rev Immunol. 2017;36(2):108–121. 10.1080/08830185.2016.1255883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, et al. : Foodborne transmission of Nipah virus, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1888–94. 10.3201/eid1212.060732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luby SP, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, et al. : Recurrent zoonotic transmission of Nipah virus into humans, Bangladesh, 2001-2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(8):1229–35. 10.3201/eid1508.081237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luby SP, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ: Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(11):1743–8. 10.1086/647951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arunkumar G, Abdulmajeed J, Santhosha D, et al. : Persistence of Nipah Virus RNA in Semen of Survivor. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(2):377–378. 10.1093/cid/ciy1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 32. Uyeki TM, Erickson BR, Brown S, et al. : Ebola Virus Persistence in Semen of Male Survivors. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(12):1552–1555. 10.1093/cid/ciw202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paz-Bailey G, Rosenberg ES, Doyle K, et al. : Persistence of Zika Virus in Body Fluids - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2017;379(13):1234–1243. 10.1056/NEJMoa1613108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 34. Sejvar JJ, Hossain J, Saha SK, et al. : Long-term neurological and functional outcome in Nipah virus infection. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(3):235–42. 10.1002/ana.21178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan CT, Goh KJ, Wong KT, et al. : Relapsed and late-onset Nipah encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2002;51(6):703–8. 10.1002/ana.10212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 36. Abdullah S, Chang LY, Rahmat K, et al. : Late-onset Nipah virus encephalitis 11 years after the initial outbreak: A case report. Neurol Asia. 2012;17(1):71–74. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 37. Escaffre O, Borisevich V, Carmical JR, et al. : Henipavirus pathogenesis in human respiratory epithelial cells. J Virol. 2013;87(6):3284–94. 10.1128/JVI.02576-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mathieu C, Pohl C, Szecsi J, et al. : Nipah virus uses leukocytes for efficient dissemination within a host. J Virol. 2011;85(15):7863–71. 10.1128/JVI.00549-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mathieu C, Dhondt KP, Châlons M, et al. : Heparan sulfate-dependent enhancement of henipavirus infection. mBio. 2015;6(2):e02427. 10.1128/mBio.02427-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Negrete OA, Levroney EL, Aguilar HC, et al. : EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature. 2005;436(7049):401–5. 10.1038/nature03838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 41. Negrete OA, Wolf MC, Aguilar HC, et al. : Two key residues in ephrinB3 are critical for its use as an alternative receptor for Nipah virus. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(2):e7. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 42. Bonaparte MI, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, et al. : Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(30):10652–7. 10.1073/pnas.0504887102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bossart KN, Tachedjian M, McEachern JA, et al. : Functional studies of host-specific ephrin-B ligands as Henipavirus receptors. Virology. 2008;372(2):357–71. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dhondt K, Horvat B: Henipavirus Infections: Lessons from Animal Models. Pathogens. 2013;2(2):264–87. 10.3390/pathogens2020264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Wit E, Munster VJ: Animal models of disease shed light on Nipah virus pathogenesis and transmission. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):196–205. 10.1002/path.4444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Middleton DJ, Westbury HA, Morrissy CJ, et al. : Experimental Nipah virus infection in pigs and cats. J Comp Pathol. 2002;126(2–3):124–36. 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Plowright RK, Peel AJ, Streicker DG, et al. : Transmission or Within-Host Dynamics Driving Pulses of Zoonotic Viruses in Reservoir-Host Populations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(8):e0004796. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baker ML, Schountz T, Wang LF: Antiviral immune responses of bats: a review. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013;60(1):104–16. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01528.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang LF, Anderson DE: Viruses in bats and potential spillover to animals and humans. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;34:79–89. 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wong KT, Grosjean I, Brisson C, et al. : A golden hamster model for human acute Nipah virus infection. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(5):2127–37. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63569-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guillaume V, Wong KT, Looi RY, et al. : Acute Hendra virus infection: Analysis of the pathogenesis and passive antibody protection in the hamster model. Virology. 2009;387(2):459–65. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weingartl H, Czub S, Copps J, et al. : Invasion of the central nervous system in a porcine host by nipah virus. J Virol. 2005;79(12):7528–34. 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7528-7534.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 53. Stachowiak B, Weingartl HM: Nipah virus infects specific subsets of porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30855. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. DeBuysscher BL, de Wit E, Munster VJ, et al. : Comparison of the pathogenicity of Nipah virus isolates from Bangladesh and Malaysia in the Syrian hamster. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(1):e2024. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kasloff SB, Leung A, Pickering BS, et al. : Pathogenicity of Nipah henipavirus Bangladesh in a swine host. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5230. 10.1038/s41598-019-40476-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Leon AJ, Borisevich V, Boroumand N, et al. : Host gene expression profiles in ferrets infected with genetically distinct henipavirus strains. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(3):e0006343. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 57. Clayton BA, Middleton D, Bergfeld J, et al. : Transmission routes for nipah virus from Malaysia and Bangladesh. Emerging Infect Dis. 2012;18(12):1983–93. 10.3201/eid1812.120875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 58. Dups J, Middleton D, Long F, et al. : Subclinical infection without encephalitis in mice following intranasal exposure to Nipah virus-Malaysia and Nipah virus-Bangladesh. Virol J. 2014;11:102. 10.1186/1743-422X-11-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dhondt KP, Mathieu C, Chalons M, et al. : Type I interferon signaling protects mice from lethal henipavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(1):142–51. 10.1093/infdis/jis653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yun T, Park A, Hill TE, et al. : Efficient reverse genetics reveals genetic determinants of budding and fusogenic differences between Nipah and Hendra viruses and enables real-time monitoring of viral spread in small animal models of henipavirus infection. J Virol. 2015;89(2):1242–53. 10.1128/JVI.02583-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marianneau P, Guillaume V, Wong T, et al. : Experimental infection of squirrel monkeys with nipah virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(3):507–10. 10.3201/eid1603.091346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Geisbert TW, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Hickey AC, et al. : Development of an acute and highly pathogenic nonhuman primate model of Nipah virus infection. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10690. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cong Y, Lentz MR, Lara A, et al. : Loss in lung volume and changes in the immune response demonstrate disease progression in African green monkeys infected by small-particle aerosol and intratracheal exposure to Nipah virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(4):e0005532. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 64. Hammoud DA, Lentz MR, Lara A, et al. : Aerosol exposure to intermediate size Nipah virus particles induces neurological disease in African green monkeys. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(11):e0006978. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 65. Liu J, Coffin KM, Johnston SC, et al. : Nipah virus persists in the brains of nonhuman primate survivors. JCI Insight. 2019;4(14): pii: 129629. 10.1172/jci.insight.129629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 66. Mire CE, Satterfield BA, Geisbert JB, et al. : Pathogenic Differences between Nipah Virus Bangladesh and Malaysia Strains in Primates: Implications for Antibody Therapy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30916. 10.1038/srep30916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 67. Rockx B, Bossart KN, Feldmann F, et al. : A novel model of lethal Hendra virus infection in African green monkeys and the effectiveness of ribavirin treatment. J Virol. 2010;84(19):9831–9. 10.1128/JVI.01163-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lo MK, Miller D, Aljofan M, et al. : Characterization of the antiviral and inflammatory responses against Nipah virus in endothelial cells and neurons. Virology. 2010;404(1):78–88. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mathieu C, Guillaume V, Sabine A, et al. : Lethal Nipah Virus Infection Induces Rapid Overexpression of CXCL10. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32157. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rockx B, Brining D, Kramer J, et al. : Clinical outcome of henipavirus infection in hamsters is determined by the route and dose of infection. J Virol. 2011;85(15):7658–71. 10.1128/JVI.00473-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mathieu C, Legras-Lachuer C, Horvat B: Transcriptome Signature of Nipah Virus Infected Endothelial Cells.In: Amezcua-Guerra LM editor. Advances in the Etiology, Pathogenesis and Pathology of Vasculitis. InTech; 2011. 10.5772/21512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Andrejeva J, Childs KS, Young DF, et al. : The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN- promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(49):17264-9. 10.1073/pnas.0407639101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ciancanelli MJ, Volchkova VA, Shaw ML, et al. : Nipah virus sequesters inactive STAT1 in the nucleus via a P gene-encoded mechanism. J Virol. 2009;83(16):7828–41. 10.1128/JVI.02610-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Parisien JP, Bamming D, Komuro A, et al. : A Shared Interface Mediates Paramyxovirus Interference with Antiviral RNA Helicases MDA5 and LGP2. J Virol. 2009;83(14):7252–60. 10.1128/JVI.00153-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rodriguez JJ, Cruz CD, Horvath CM: Identification of the Nuclear Export Signal and STAT-Binding Domains of the Nipah Virus V Protein Reveals Mechanisms Underlying Interferon Evasion. J Virol. 2004;78(10):5358–67. 10.1128/jvi.78.10.5358-5367.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Satterfield BA, Cross RW, Fenton KA, et al. : Nipah Virus C and W Proteins Contribute to Respiratory Disease in Ferrets. J Virol. 2016;90(14):6326–6343. 10.1128/JVI.00215-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 77. Shaw ML, García-Sastre A, Palese P, et al. : Nipah virus V and W proteins have a common STAT1-binding domain yet inhibit STAT1 activation from the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, respectively. J Virol. 2004;78(11):5633–41. 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5633-5641.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shaw ML, Cardenas WB, Zamarin D, et al. : Nuclear localization of the Nipah virus W protein allows for inhibition of both virus- and toll-like receptor 3-triggered signaling pathways. J Virol. 2005;79(10):6078–88. 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6078-6088.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schountz T, Campbell C, Wagner K, et al. : Differential Innate Immune Responses Elicited by Nipah Virus and Cedar Virus Correlate with Disparate In Vivo Pathogenesis in Hamsters. Viruses. 2019;11(3): pii: E291. 10.3390/v11030291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 80. Sánchez-Aparicio MT, Feinman LJ, García-Sastre A, et al. : Paramyxovirus V Proteins Interact with the RIG-I/TRIM25 Regulatory Complex and Inhibit RIG-I Signaling. J Virol. 2018;92(6): pii: e01960-17. 10.1128/JVI.01960-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 81. Rodriguez KR, Horvath CM: Amino acid requirements for MDA5 and LGP2 recognition by paramyxovirus V proteins: A single arginine distinguishes MDA5 from RIG-I. J Virol. 2013;87(5):2974–8. 10.1128/JVI.02843-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yamaguchi M, Kitagawa Y, Zhou M, et al. : An anti-interferon activity shared by paramyxovirus C proteins: Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 7/9-dependent alpha interferon induction. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(1):28–34. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bharaj P, Wang YE, Dawes BE, et al. : The Matrix Protein of Nipah Virus Targets the E3-Ubiquitin Ligase TRIM6 to Inhibit the IKKε Kinase-Mediated Type-I IFN Antiviral Response. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(9):e1005880. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sugai A, Sato H, Takayama I, et al. : Nipah and Hendra Virus Nucleoproteins Inhibit Nuclear Accumulation of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2 by Interfering with Their Complex Formation. J Virol. 2017;91(21): pii: e01136–17. 10.1128/JVI.01136-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 85. Arunkumar G, Devadiga S, McElroy AK, et al. : Adaptive immune responses in humans during Nipah virus acute and convalescent phases of infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2019. 10.1093/cid/ciz010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 86. Pickering BS, Hardham JM, Smith G, et al. : Protection against henipaviruses in swine requires both, cell-mediated and humoral immune response. Vaccine. 2016;34(40):4777–86. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lara A, Cong Y, Jahrling PB, et al. : Peripheral immune response in the African green monkey model following Nipah-Malaysia virus exposure by intermediate-size particle aerosol. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(6):e0007454. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 88. Keshwara R, Shiels T, Postnikova E, et al. : Rabies-based vaccine induces potent immune responses against Nipah virus. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:15. 10.1038/s41541-019-0109-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 89. Walpita P, Cong Y, Jahrling PB, et al. : A VLP-based vaccine provides complete protection against Nipah virus challenge following multiple-dose or single-dose vaccination schedules in a hamster model. NPJ Vaccines. 2017;2:21. 10.1038/s41541-017-0023-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 90. van Doremalen N, Lambe T, Sebastian S, et al. : A single-dose ChAdOx1-vectored vaccine provides complete protection against Nipah Bangladesh and Malaysia in Syrian golden hamsters. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(6):e0007462. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 91. Parvege MM, Rahman M, Nibir YM, et al. : Two highly similar LAEDDTNAQKT and LTDKIGTEI epitopes in G glycoprotein may be useful for effective epitope based vaccine design against pathogenic Henipavirus. Comput Biol Chem. 2016;61:270–80. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Saha CK, Mahbub Hasan M, Saddam Hossain M, et al. : In silico identification and characterization of common epitope-based peptide vaccine for Nipah and Hendra viruses. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2017;10(6):529–38. 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 93. DeBuysscher BL, Scott D, Marzi A, et al. : Single-dose live-attenuated Nipah virus vaccines confer complete protection by eliciting antibodies directed against surface glycoproteins. Vaccine. 2014;32(22):2637–44. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. DeBuysscher BL, Scott D, Thomas T, et al. : Peri-exposure protection against Nipah virus disease using a single-dose recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine. NPJ Vaccines. 2016;1: pii: 16002. 10.1038/npjvaccines.2016.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Prescott J, DeBuysscher BL, Feldmann F, et al. : Single-dose live-attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus disease. Vaccine. 2015;33(24):2823–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bossart KN, Zhu Z, Middleton D, et al. : A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against lethal disease in a new ferret model of acute nipah virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(10):e1000642. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bossart KN, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, et al. : A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects african green monkeys from hendra virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(105):105ra103. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Guillaume-Vasselin V, Lemaitre L, Dhondt KP, et al. : Protection from Hendra virus infection with Canarypox recombinant vaccine. NPJ Vaccines. 2016;1:16003. 10.1038/npjvaccines.2016.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ploquin A, Szécsi J, Mathieu C, et al. : Protection against henipavirus infection by use of recombinant adeno-associated virus-vector vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(3):469–78. 10.1093/infdis/jis699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Hotard AL, He B, Nichol ST, et al. : 4’-Azidocytidine (R1479) inhibits henipaviruses and other paramyxoviruses with high potency. Antiviral Res. 2017;144:147–152. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 101. Lo MK, Jordan PC, Stevens S, et al. : Susceptibility of paramyxoviruses and filoviruses to inhibition by 2′-monofluoro- and 2′-difluoro-4′-azidocytidine analogs. Antiviral Res. 2018;153:101–13. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 102. Dawes BE, Kalveram B, Ikegami T, et al. : Favipiravir (T-705) protects against Nipah virus infection in the hamster model. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7604. 10.1038/s41598-018-25780-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 103. Guedj J, Piorkowski G, Jacquot F, et al. : Antiviral efficacy of favipiravir against Ebola virus: A translational study in cynomolgus macaques. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002535. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mathieu C, Porotto M, Figueira TN, et al. : Fusion Inhibitory Lipopeptides Engineered for Prophylaxis of Nipah Virus in Primates. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(2):218–227. 10.1093/infdis/jiy152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Lo MK, Feldmann F, Gary JM, et al. : Remdesivir (GS-5734) protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(494): pii: eaau9242. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 106. Friedrich MJ: Multidrug Ebola Trial Underway in Democratic Republic of Congo. JAMA. 2019;321(7):637. 10.1001/jama.2019.0593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]