Abstract

Background

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a pathological condition affecting older men. BPH complications often lead to deterioration in the quality of life. Serenoa repens (Saw Palmetto) is used for treating lower urinary tract infections in traditional medicine.

Methods

This study was performed to compare the efficacy of β-sitosterol enriched saw palmetto oil (VISPO) and conventional saw palmetto oil (SPO) extracted using supercritical fluid extraction, in alleviating the BPH complications using testosterone-induced BPH model rats. The animals received testosterone (5 mg/kg s.c.) with or without SPO and VISPO (200 and 400 mg/kg b.w.) or Finasteride (1 mg/kg b.w.) p.o. for 28 days. At the end of the experiment, overnight fasted animals were euthanized, blood samples collected for serum analysis of testosterone. Prostate tissue histomorphology was examined by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Western blot analysis was performed using prostate tissue homogenates.

Results

VISPO exhibited superior efficacy compared to SPO as evident from the significant decrease in prostate weight to body weight ratio, serum testosterone level and increase in growth inhibition of prostate tissue compared to BPH group (p < 0.001). Histological examination of prostate tissue samples showed that VISPO treatment was comparatively better than SPO in improving the hyperplastic patterns. Further, VISPO significantly regulated the expression of inflammatory and apoptotic marker proteins in BPH rats.

Conclusion

Our data provide experimental evidence that β-sitosterol enriched saw palmetto oil could be higher efficacious in treating the BPH complications compared to the conventional saw palmetto oil preparations.

Keywords: Prostate enlargement, Inflammation, Cell death, Herbal medicine

Background

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is an age-related benign proliferative disease affecting males [1]. BPH is characterised by benign enlargement of prostate deteriorating quality of life in older men [2, 3]. BPH complications have been evident in 20% of the male population in their 50s and the prevalence increased to > 35% in men aging 70 and above [4]. BPH is characterized by the increased proliferation of stromal and glandular epithelial cells resulting in the enlargement of prostate size and weight [5]. Androgens play a key role in the progression of BPH. Conversion of circulating testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5α-reductase in the prostate mediates BPH via regulation of androgen receptor transcription [6].

Experimental data from previous studies have demonstrated a relationship between inflammation of the prostate and BPH development [7, 8]. Inflammatory infiltrates were detected in the prostate tissue indicating chronic inflammation could be a cause of BPH [9]. Earlier reports also suggest that there occurs an upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins correlated with the expression of Cox-2 causing a reduction in prostate tissue cell death [10]. Elevated levels of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) have been shown in BPH and prostate cancer [11]. Hence stimulation of apoptosis could be a promising strategy in the treatment of BPH [12].

Current treatments for BPH are based on strategies such as inhibition of 5α-reductase, attenuation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and blocking of α-adrenoreceptors. Inhibitors of 5α-reductase suppress the conversion of testosterone into a more potent metabolite, 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) [13]. Alpha blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors improve the BPH symptom and maximal urine flow rate. However, these are associated with side effects such as erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, and reduced semen count [14, 15]. Herbal medicine for the treatment of BPH and associated complications has drawn attention in the recent past, due to the minimal side effects [16, 17].

Serenoa repens commonly known as American dwarf Saw palmetto plant contains bioactive compounds such as phytosterols, fatty acids and their ethyl esters derived from dried fruits [18]. Herbal preparations from Saw palmetto have been used for the treatment of BPH. Saw palmetto products had been evaluated clinically against BPH [19]. The pharmacological effects of saw palmetto extract have been previously studied in experimental animal models of BPH [20]. Oki et al. have reported the effect of saw palmetto extract on urodynamic symptoms and micturition reflux in a rat model [21]. In another study saw palmetto whole berry and extract were demonstrated to have efficacy in influencing BPH by reducing the androgen-induced prostate enlargement [22]. Recently, Pais et al. reported the 5-α reductase inhibitory potential of saw palmetto supercritical CO2 extract using a cell-free in vitro test system [23]. The present study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of VISPO, a novel supercritical CO2 extract of saw palmetto fruits with higher β-sitosterol content (3%). The results were compared with the conventional saw palmetto oil (SPO). We have observed higher efficacy of VISPO, alleviating the BPH complications as evident from the in vivo experiments.

Methods

Saw palmetto oil preparations

SPO and VISPO supercritical CO2 extracts were procured from the Department of Phytochemistry, R&D Centre for Excellence, Vidya Herbs Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore. The samples were reconstituted in 0.1% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) for in vivo experiments.

Chemicals and reagents

β-sitosterol (95%) (Sigma Aldrich), LCMS grade methanol and acetonitrile from J.T. Baker (Philipsburg, NJ, USA), Testosterone (Himedia), Finasteride (Dr. Reddy’s Laboratory, India), Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). Antibodies against cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2), nuclear factor kappa B-p65 (NF-kB-p65), Akt, pAkt, caspase-9, Bcl-2, Bax, β-actin and HRP-conjugated goat IgG antibody, were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) analysis

The SPO and VISPO extracts were analyzed for β-sitosterol content by LCMS/MS using Shimadzu triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with Nexera X2 UPLC System (LCMS-8050). The chromatographic separation was achieved using analytical column: Kinetex C18 (2.1 × 150 mm, Phenomenex), temperature 40 °C, the detection wavelength 205 nm. The isocratic elution was carried out with the mobile phase composition methanol: acetonitrile (40:60), flow rate: 0.5 ml/min, injection volume: 5 μl.

Animals

Forty-two male Wistar rats (10-week-old) were purchased from Biogen, Bangalore, India (CPCSEA Reg. No.971/bc/06). The animals were housed in accordance with the CPCSEA (Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals) guidelines. After a one-week acclimatization period the animals were housed in rooms maintained at 22 ± 2 °C and 30–70% humidity. Water and standard pellet diet were given ad libitum. The animal experiments were conducted after due clearance from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of Vidya Herbs (P) Ltd. (VHPL/PCL/IAEC/08/18).

BPH induction and dosage

The animals were divided into seven groups of six rats each. Group I rats received 0.1% CMC in saline and served as normal control. Group II animals (BPH control) were administered with a daily dose of 5 mg/kg testosterone subcutaneously for 28 days. In groups III-VII, BPH was induced in rats using testosterone 5 mg/kg in olive oil subcutaneously and a simultaneous treatment with different doses of SPO, VISPO (200 and 400 mg/kg b.w.) or Finasteride (1 mg/kg b.w.) p.o., for 28 days, respectively. At the end of the treatment period, blood was collected prior to the necropsy. Animals were sacrificed by an overdose of gaseous anesthesia (isoflurane) in an anesthetic chamber. The vital parameters such as prostate weight, prostate weight to body weight ratio, growth inhibition of prostate, serum testosterone level, expression of inflammatory and apoptotic proteins in prostate tissue were evaluated.

Prostate weight

Prostate tissues were excised, rinsed and weighed immediately after removal. The PW/BW ratio was calculated using the following equation: PW/BW ratio = (Prostate weight of each animal from the experimental group / Body weight of each animal from the experimental group) × 1000. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated as follows: 100 – [(treated group – control group) / (BPH group – control group)] × 100.

Determination of testosterone in serum

Blood samples were collected at the end of the experiment; coagulated at room temperature for 20 min. Serum was separated by centrifuging at 3000 g, 4 °C. Serum samples were analyzed for testosterone levels using commercial ELISA kit (582,701; Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Histological examination

The prostate tissue samples were fixed in 4% formalin, dehydrated with a graded alcohol series, embedded in paraffin, and then cut into 4 μm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The images were captured using a microscope (Leica, Germany).

Western blot analysis

The prostatic tissue from each animal was homogenized in lysis buffer and incubated for 20 min to induce cell lysis. Tissue extracts were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatants were transferred to clean tubes. Aliquots of protein samples (30 μg) were resolved on 8–15% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred on to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated for 1 h with blocking solution and subsequently incubated with 1:500 dilution of primary antibodies for NF-kB-p65 (sc-8008), Cox-2 (sc-19,999), Akt (sc-56,878), pAkt (sc-514,032), caspase-9 (sc-73,548), Bcl-2 (sc-7382) and Bax (sc-20,067) overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in TBS followed by incubation with Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat IgG antibody (1:4000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was performed on ImageQuant™ LAS 500 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Densitometry analyses of the results were made using Image J software (version 1.46, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland). β-actin was used as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparison between groups was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s t-test. The data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

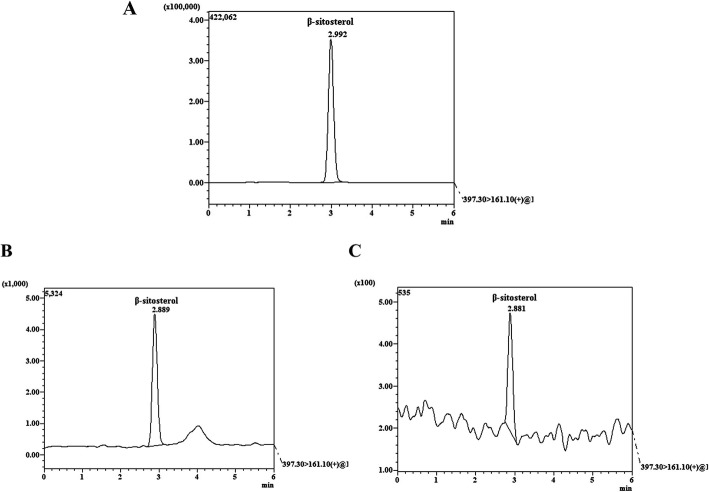

LCMS analysis of saw palmetto oil preparations

The saw palmetto oils were quantified for the β-sitosterol content. LCMS analysis revealed the presence of 0.2 and 3% of β-sitosterol in SPO and VISPO respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

LCMS/MS analysis of saw palmetto extracts. a Standard β-sitosterol, b VISPO and c SPO

VISPO prevents hyperplasia in testosterone-induced BPH

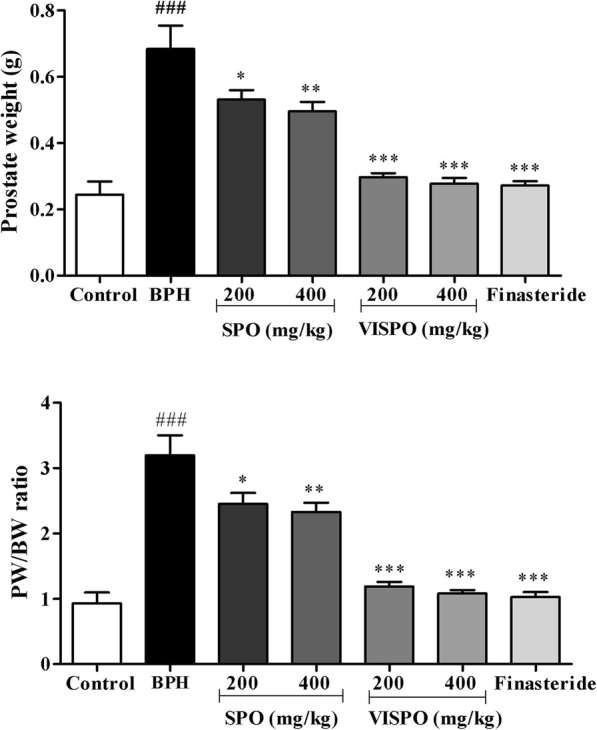

The mean prostate weight of animals in the BPH group was significantly increased as compared to the normal rats (p < 0.001) indicating that testosterone-induced BPH in rats. The prostate weights were reduced considerably in the Finasteride and VISPO treated groups (p < 0.001). There was a dose-dependent decrease in prostate weight in extract treated animals (Fig. 2). The prostate weight in BPH group was 2.83-fold higher than control rats (Table 1). The treated groups exhibited an appreciable reduction in the prostate weight. There was a reduction of 1.28 and 1.38-fold in prostate weight of 200 and 400 mg/kg SPO treated rats respectively. Interestingly, VISPO treated groups markedly decreased the prostate weight compared to BPH group (p < 0.001). 400 mg/kg treatment of VISPO reduced the prostate weight by 2.43-fold which was comparable to Finasteride treatment (2.51 fold). The percentage growth inhibition of prostate was 90.9% at 400 mg/kg VISPO treated group. Further, PW/BW ratio in BPH group was significantly increased as compared to control group (p < 0.001). Administration of VISPO showed superior efficacy in reducing the PW/BW ratio, as compared to SPO treatment.

Fig. 2.

Effect of SPO and VISPO on prostate weight and prostate to body weight (PW/BW) ratio. The data were analyzed by one way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s t-test. ## p < 0.01 vs. control group. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 vs. the BPH group

Table 1.

Prostate growth in BPH model rats

| Group | Prostate weight (g) | Inhibition of growth (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.24 ± 0.04 | – |

| BPH | 0.68 ± 0.07### | – |

| SPO (200 mg/kg) | 0.53 ± 0.03* | 34.09 |

| SPO (400 mg/kg) | 0.49 ± 0.03** | 43.18 |

| VISPO (200 mg/kg) | 0.29 ± 0.01*** | 88.63 |

| VISPO (400 mg/kg) | 0.28 ± 0.02*** | 90.9 |

| Finasteride (1 mg/kg) | 0.27 ± 0.01*** | 93.18 |

The data were represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ###p < 0.001 vs. control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs. BPH group. Growth inhibition = 100 – ((treated group-control group) / (BPH group-control group) × 100)

SPO Saw palmetto oil, VISPO Standardized saw palmetto oil

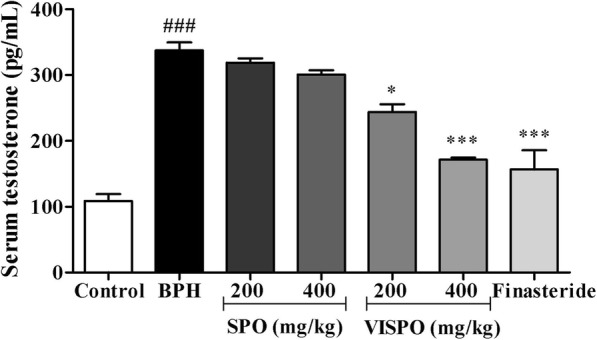

VISPO restores the serum testosterone level in BPH rats

The serum testosterone level was significantly higher in BPH group (337.5 ± 12.15 pg/mL) as compared to control rats (108.6 ± 14.92 pg/mL). As shown in Fig. 3, the level of testosterone was markedly decreased in the treatment groups. The values were highly significant in 400 mg/kg VISPO treated group and comparable to Finasteride (p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Effect of SPO and VISPO on serum testosterone level. The data were analyzed by one way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s t-test. ###p < 0.001 vs. control group. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. the BPH group

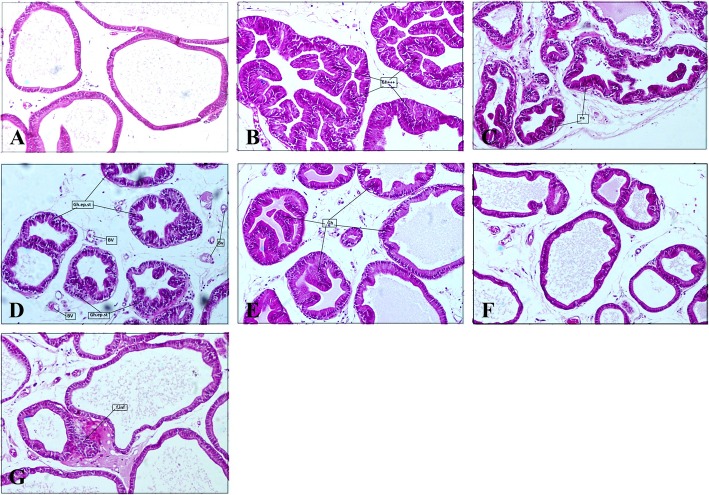

VISPO suppressed the hyperplastic patterns in prostate tissue of BPH rats

Histological examination of prostate tissue revealed that the testosterone treatment induced glandular hyperplasia with decreased glandular luminal area compared to the control animals (Fig. 4b). SPO (200 and 400 mg/kg) and 200 mg/kg VISPO treatment groups exhibited moderate suppression of prostate hyperplasia patterns (Fig. 4c-e). 400 mg/kg VISPO treatment markedly restored the cellular architecture in BPH rats (Fig. 4f). The epithelial cell thickness was reduced, and the luminal area increased considerably. The finasteride group also showed near normal prostatic glands with mild focal inflammation (Fig. 4g).

Fig. 4.

Effects of VISPO administration on prostate hyperplasia. Prostate tissues were fixed, sectioned at 4 μm thickness, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, magnification, × 100). a Vehicle control, b BPH/vehicle, c BPH/SPO 200 mg/kg, d BPH/SPO 400 mg/kg, e BPH/VISPO 200 mg/kg, f BPH/VISPO 400 mg/kg and g BPH/Finasteride 1 mg/kg

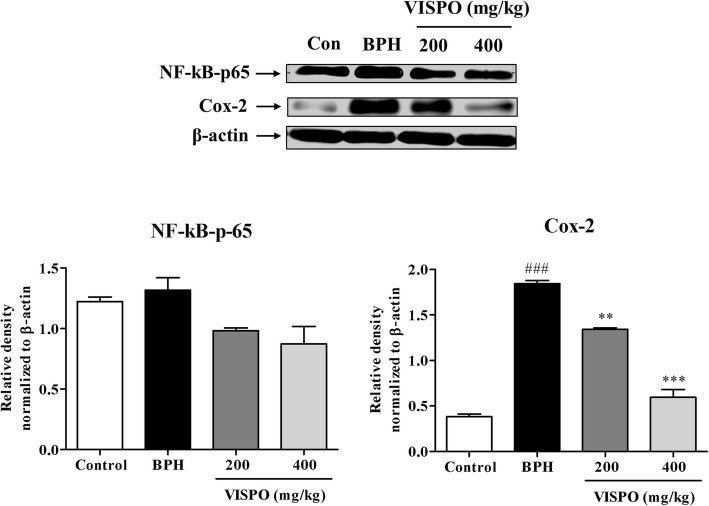

VISPO regulated the expression of inflammatory and apoptotic markers in BPH rats

Testosterone treatment markedly increased the expression of NF-kB (p < 0.05) and Cox-2 (p < 0.001) in prostate tissue of BPH rats as compared to control group. However, treatment with VISPO significantly down-regulated the expression of these proteins in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of VISPO administration on the expression of NF-kB and Cox-2 in prostate tissue of BPH model rats. The protein expression was determined by western blotting using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as loading control. Densitometric analysis was performed using Image J software. The data presented as mean ± SEM (###p < 0.001 vs. Control group; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs. BPH group)

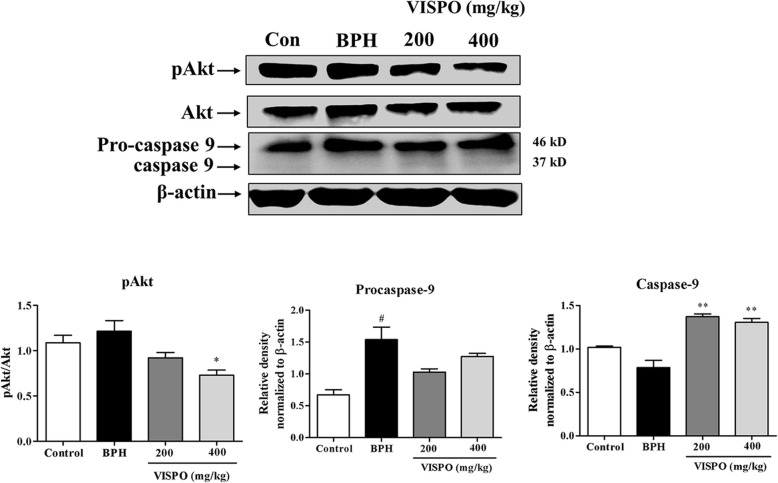

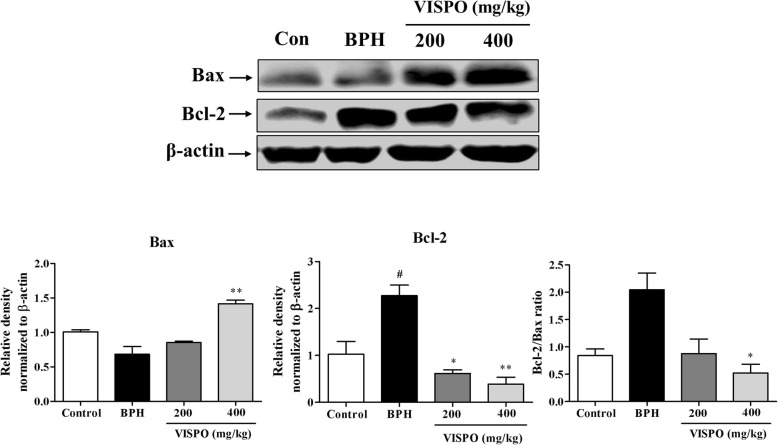

In the prostate tissue of BPH rats there was an obvious increase in the expression of pAkt. Also, VISPO treatment effectively downregulated the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473. There was a considerable decrease in the procaspase-9 level in the prostate tissue of BPH rats after treatment with respective doses of VISPO (Fig. 6). Further, VISPO treated groups showed a significant decrease in the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, but increased expression of proapoptotic Bax as compared to BPH group (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Effect of VISPO administration on the expression of pAkt and caspase-9 in prostate tissue of BPH model rats. The protein expression was determined by western blotting using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as loading control. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software. The data presented as mean ± SEM (#p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001 vs. control group; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs. BPH group)

Fig. 7.

Effect of VISPO administration on the expression of Bcl-2 family in prostate tissue of BPH model rats. The protein expression was determined by western blotting using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as loading control. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software. The data presented as mean ± SEM (#p < 0.05 vs. control group; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. BPH group)

Discussion

BPH is a common prostate disease affecting older men. It is a major cause of lower urinary tract symptoms deteriorating the quality of life [24]. The BPH pathogenesis has been associated with factors such as genetic predisposition, hormonal imbalance, imbalance in cell proliferation and death and inflammation [25]. The current therapy for BPH involves administration of 5-α reductase inhibitors, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and laser therapy [13, 26]. Nevertheless, these treatments improve the quality of life some of the patients may feel worse due to side effects of the treatment. For example, Finasteride is a 5-α reductase inhibitor used for treating BPH, effectively alleviating the complication [27]. However, Finasteride is also associated with undesirable side effects such as erectile dysfunction, increased risk of impotency, and ejaculation disorder. This has led to the search for alternative therapies with fewer side effects for the treatment of BPH [28]. A large body of evidence suggest the promising role of phytotherapy for the management of BPH [29].

S. repens (Saw palmetto), an evergreen shrub is used long since for the treatment of BPH. Medicinal preparations from saw palmetto, particularly the ripe berries are used to alleviate the symptoms of BPH [30]. It has also been reported that saw palmetto extracts are used to treat prostate cancer in men as alternative medicine [31]. In the present study we have investigated the efficacy of a standardized Saw palmetto oil prepared from supercritical fluid extraction, with higher β-sitosterol content (VISPO) in BPH model rats. The results were compared with conventional saw palmetto oil (SPO).

BPH is primarily characterized by the enlargement of the prostate [32]. In the present study, the testosterone-induced BPH group demonstrated increased prostate weight and PW/BW ratio compared with the control group. A 21 day-treatment of BPH model rats with SPO, VISPO and Finasteride significantly inhibited this increase in prostate weight and PW/BW ratio. It was interesting to observe that VISPO exhibited superior inhibition of prostate weight (p < 0.001) compared to SPO. VISPO showed 48% increase in the growth inhibition percentage (90.9%) in comparison to SPO treated group (43.18%) at 400 mg/kg dose. Prostate cell growth in BPH is influenced by the circulating testosterone that acts locally via the production of necessary growth factors [33]. There was a significant decrease in the serum testosterone levels following VISPO administration in BPH rats, comparable to Finasteride treated group. These preliminary results prompted us to further address the biomechanism of VISPO mediated alleviation of BPH.

Experimental data from previous studies suggest that a strong correlation exist between inflammation and BPH. The pro-inflammatory cytokines-induced expression of inflammatory mediators such as Cox-2 and iNOS contribute to prostate enlargement [34]. In agreement with this, we have observed that the Cox-2 levels were increased in the BPH group. However, VISPO treatment dose-dependently decreased the protein level. Further, treatment with 400 mg/kg VISPO significantly downregulated the Cox-2 expression compared to BPH group (p < 0.001). It is well known that NF-kB stimulates the expression of proteins contributing to the pathogenesis of inflammation. In fact, activation of NF-kB is a hallmark of inflammation [35]. In the present study, expression of NF-kB in the prostate tissue of BPH rats was considerably increased as compared to control animals. VISPO treatment suppressed the NF-kB expression compared with that of animals in the BPH group. These data suggest possible anti-inflammatory effects of VISPO in the treatment of BPH.

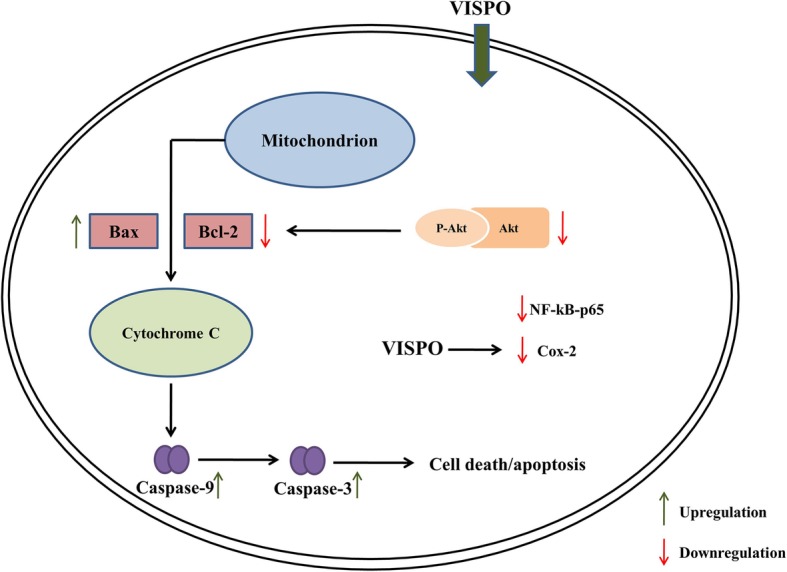

Activation of Akt has been shown to facilitate cell survival against apoptotic stimuli. Available data from previous literature reveal that activation of Akt up-regulates the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 through cAMP-response Element-binding protein (CREB) [36]. In agreement to this, we noticed an increase in the expression of pAkt and Bcl-2 in prostate tissue of testosterone-induced BPH rats. However, VISPO treatment induced apoptosis by significantly downregulating these proteins. The pro-apoptotic protein Bax was upregulated by VISPO. There was an appreciable decrease in the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax following treatment with VISPO. The expression of procaspase-9 was markedly down-regulated by the VISPO treatment compared to BPH control rats. These data suggested that VISPO induced apoptosis through the regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins leading to a caspase-dependent pathway (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism for the efficacy of VISPO in BPH model rats

The improved efficacy of the present intervention, VISPO in comparison with conventional saw palmetto oil could be attributed to the higher content of β-sitosterol in the extract. Phytosterols have been well-documented for having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anticancer effects [37–39]. Previous studies have reported the potential anti-inflammatory activity of β-sitosterol using in vitro and in vivo models [40, 41]. Enriched content of β-sitosterol in VISPO could possibly contribute to the anti-inflammatory effect in BPH model. Also, in the present study it was found that VISPO exerted the proapoptotic actions in prostate tissue of BPH rats. It has been reported earlier that β-sitosterol induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by activating the sphingomyelin cycle [42].

The major pathway for testosterone metabolism in BPH is its conversion into more active form, dihydroxytestosterone (DHT) via 5α- reductase [43]. Cabeza et al., reported the effect of β-sitosterol in BPH as a function of 5α- reductase inhibition [44]. Several clinical studies have previously demonstrated the positive effects of phytosterols (β-sitosterol) on the quality of life in patients with BPH [45, 46]. Clinical data suggest that treatment with β-sitosterol significantly increase the urine flow and decrease the post-void residual volume [47]. Results from our study clearly indicate a plausible role of β-sitosterol for the improvement in the efficacy of saw palmetto oil.

Conclusion

The β-sitosterol enriched saw palmetto oil was found to be more efficacious than the conventional saw palmetto oil, in preventing the pathogenesis of BPH in rats. The present study for the first time demonstrates the enhancing efficacy of saw palmetto oil attributable to its higher β-sitosterol content. Further clinical interventions pertaining to the safety and efficacy will clearly define the therapeutic potential of VISPO in the treatment of BPH.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Lingaraju HB and Mr. Stanley Anchan for providing the analytical support and Dr. Gouthamchandra K. for experimental advice.

Abbreviations

- Akt

Protein Kinase B

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X Protein

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- BPH

Benign Prostate Hyperplasia

- BW

Body weight

- CMC

Carboxymethyl Cellulose

- Cox-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- CPCSEA

Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals

- CREB

cAMP-response Element-binding protein

- DHT

Dihydroxytestosterone

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- IAEC

Institutional Animal Ethics Committee

- IAP

Inhibitors of Apoptosis Proteins

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IkB

Inhibitor of Kappa B

- iNOS

inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase

- LCMS

Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

- NF-kB

Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- pAkt

Phosphorylated Protein Kinase B

- PW

Prostate weight

- SPO

Conventional saw palmetto oil

- VISPO

β-sitosterol enriched saw palmetto oil

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, KS; experimental design, HVS, animal experimentation and western blot analysis, KV, BA, HVS; analytical support, A; writing – original draft preparation, KV; writing – review and editing, HVS; supervision, KS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Vidya Herbs (P) Ltd.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol contained in the present research has been approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of Vidya Herbs (P) Ltd.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We have read and understood the BMC policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: All the authors are employees of Vidya Herbs (P) Ltd. that funded the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Heggar V. Sudeep, Phone: +91 80-42094158, Email: sudeepkashyap.82@gmail.com

Karempudi Venkatakrishna, Email: kvkrishna09@gmail.com.

Ballal Amrutharaj, Email: raj.amrith20@gmail.com.

Anitha, Email: anithasonale@gmail.com.

Kodimule Shyamprasad, Email: shyamprasad@vidyaherbs.com.

References

- 1.De Nunzio C, Albisinni S, Gacci M, Tubaro A. The role of inflammation in the progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2013;8(2):142–149. doi: 10.1007/s11884-013-0179-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roehrborn CG. Male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu C, Kapoor A. Dutasteride for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:1399–1408. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.797965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SWH, Chan EMC, Lai YK. The global burden of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06628-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schauer IG, Rowley DR. The functional role of reactive stroma in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Differentiation. 2011;8:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chughtai B, Forde JC, Thomas DDM, Laor L, Hossack T, Woo HH, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16031. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert G, Descazeaud A, Nicolaiew N, Terry S, Sirab N, Vacherot F, et al. Inflammation in benign prostatic hyperplasia: a 282 patients’ immunohistochemical analysis. Prostate. 2009;69(16):1774–1780. doi: 10.1002/pros.21027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chughtai B, Lee R, Te A, Kalpan S. Role of inflammation in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev Urol. 2011;13(3):147–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latil A, Petrissans MT, Roquet J, Robert G, de la Taille A. Effects of hexanic extract of Serenoa Repens (Permixon® 160 mg) on inflammation biomarkers in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 2015;75:1857–1867. doi: 10.1002/pros.23059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Bergh A, Damber JE. Chronic inflammation in benign prostate hyperplasia is associated with focal upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2, Bcl-2, and cell proliferation in the glandular epithelium. Prostate. 2004;61(1):60–72. doi: 10.1002/pros.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-Berriguete G, Fraile B, de Bethencourt FR, Prieto-Folgado A, Bartolome N, Nunez C, et al. Role of IAPs in prostate cancer progression: immunohistochemical study in normal and pathological (benign hyperplastic, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer) human prostate. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:18–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minutoli L, Altavilla D, Marini H, Rinaldi M, Irrera N, Pizzino G, et al. Inhibitors of apoptosis proteins in experimental benign prostatic hyperplasia: effects of Serenoa repens, selenium and lycopene. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:19. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-21-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.McVary KT. A review of combination therapy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Ther. 2007;29(3):387–398. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(07)80077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiwrajka M, Yaxley W, Ranasinghe S, Perera M, Roberts MJ, Yaxley J. Drugs for benign prostatic hypertrophy. Aust Prescr. 2018;41(5):150–153. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2018.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naslund MJ, Miner M. A review of the clinical efficacy and safety of 5α-reductase inhibitors for the enlarged prostate. Clin Ther. 2007;29:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vyas BA, Desai NY, Patel PK, Joshi SV, Shah DR. Effect of Boerhaavia diffusa in experimental prostatic hyperplasia in rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45:264–269. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.111946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allkanjari O, Vitalone A. What do we know about phytotherapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia? Life Sci. 2015;126:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Booker A, Suter A, Krnjic A, Strassel B, Zloh M, Said M, et al. A phytochemical comparison of saw palmetto products using gas chromatography and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolomic profiling. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;66(6):811–822. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timothy JW, Areef I, Gerold S, Roderick MD, Joseph L, Cynthia M. Saw palmetto extracts for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1604–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki M, Ito Y, Fujino T, Abe M, Umegaki K, Onoue S, et al. Pharmacological effects of saw palmetto extract in the lower urinary tract. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30(3):271–281. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oki T, Suzuki M, Nishioka Y, Yasuda A, Umegaki K, Yamada S. Effects of saw palmetto extract on micturition reflex of rats and its autonomic receptor binding activity. J Urol. 2005;173(4):1395–1399. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000146273.26591.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talpur N, Echard B, Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Preuss HG. Comparison of saw palmetto (extract and whole berry) and Cernitin on prostate growth in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;250(1–2):21–26. doi: 10.1023/A:1024988929454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pais P, Villar A, Rull S. Determination of the potency of a novel saw palmetto supercritical CO2 extract (SPSE) for 5α-reductase isoform II inhibition using a cell-free in vitro test system. Res Rep Urol. 2016;8:41–49. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S96576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta K, Yezdani M, Sotelo T, Aragon-Ching JB. A synopsis of drugs currently in preclinical and early clinical development for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Expert Opin Investing Drugs. 2015;24:1059–1073. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1048333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawlicki B, Zielinski H, Dabrowski M. Role of apoptosis and chronic prostatitis in the pathogenesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2004;17:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Shen P, He Q, Yin X, Chen Z, Gui H, et al. Different lasers in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a network meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23503. doi: 10.1038/srep23503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickel JC, Gilling P, Tammela TL, Morrill B, Wilson TH, Rittmaster RS. Comparison of dutasteride and finasteride for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia the enlarged prostate international comparator study (EPICS) BJU Int. 2011;108:388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paba S, Frau R, Godar SS, Devot P, Marrosu F, Bortolato M. Steroid 5-reductase as a novel therapeutic target for schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:151–167. doi: 10.2174/138161211795049589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyamai DW, Arika WM, Rachuonyo HO, Wambani JR, Ngugi MP. Herbal management of benign prostate hyperplasia. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2016;8(5):130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Sat Report. 2008;10(12):1–23. [PubMed]

- 31.Bishop FL, Rea A, Lewith H, Chan YK, Saville J, Prescott P, et al. Complementary medicine use by men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:1–13. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J, Tarter TH. Combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin for the treatment of symptomatic enlarged prostate. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:251–258. doi: 10.2147/cia.s4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marinese D, Patel R, Walden PD. Mechanistic investigation of the adrenergic induction of ventral prostate hyperplasia in mice. Prostate. 2003;54:230–237. doi: 10.1002/pros.10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sciarra A, Mariotti G, Salciccia S, Autran Gomez A, Monti S, Toscano V, et al. Prostate growth and inflammation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;108:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun S. NF-kB signalling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Subbaiah P, Albina N, Carol S, Kim AH, Linda MB, Lynn EH, et al. Akt/protein kinase B up-regulates Bcl-2 expression through cAMP-response element-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(15):10761–10766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouic PJ. The role of phytosterols and phytosterolins in immune modulation: a review of the past 10 years. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2001;4:471–475. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida Y, Niki E. Antioxidant effects of phytosterol and its components. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2003;49:277–280. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.49.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagarda M, García-Llatas G, Farré R. Analysis of phytosterols in foods. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:1486–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loizou S, Lekakis I, Chrousos GP, Moutsatsou P. Beta-sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54(4):551–558. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paniagua-Pérez R, Flores-Mondragón G, Reyes-Legorreta C, Herrera Lopez B, Cervantes-Hernandez I, Madrigal-Santillan O, et al. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory capacity of beta-sitosterol in rodent assays. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2016;14(1):123–130. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Holtz RL, Fink CS, Awad AB. beta-Sitosterol activates the sphingomyelin cycle and induces apoptosis in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 1998;32(1):8–12. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith CM, Ballard SA, Wyllie MG, Masters JRW. Comparison of testosterone metabolism in benign prostatic hyperplasia and human prostate cancer cell lines in vitro. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;50(3–4):151–159. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cabeza M, Bratoeff E, Heuze I, Ramírez E, Sánchez M, Flores E. Effect of beta-sitosterol as inhibitor of 5 alpha-reductase in hamster prostate. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 2003;46:153–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coleman CI, Hebert JH, Reddy P. The effect of phytosterols on quality of life in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pharmacother. 2002;22(11):1426–1432. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.16.1426.33695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi Y, Sugaya Y, Tokue A. Clinical effects of beta-sitosterol (phytosterol) on benign prostatic hyperplasia: preliminary study. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1998;44(12):865–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berges RR, Windeler J, Trampisch HJ, Senge T. Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of beta-sitosterol in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Beta-sitosterol study group. Lancet. 1995;345(8964):1529–1532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.