Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have achieved impressive success in different cancer types, yet responses vary and predictive biomarkers are urgently needed. Growing evidence points to a link between DNA methylation and anti-tumor immunity, while clinical data on the association of genomic alterations in DNA methylation-related genes and ICI response are lacking.

Methods

Clinical cohorts with annotated response and survival data and matched mutational data from published studies were collected and consolidated. The predictive function of specific mutated genes was first tested in the discovery cohort and later validated in the validation cohort. The association between specific mutated genes and tumor immunogenicity and anti-tumor immunity was further investigated in the Cancer Genome Altas (TCGA) dataset.

Results

Among twenty-one key genes involving in the regulation of DNA methylation, TET1-mutant (TET1-MUT) was enriched in patients responding to ICI treatment in the discovery cohort (P < 0.001). TET1 was recurrently mutated across multiple cancers and more frequently seen in skin, lung, gastrointestinal, and urogenital cancers. In the discovery cohort (n = 519), significant differences were observed between TET1-MUT and TET1-wildtype (TET1-WT) patients regarding objective response rate (ORR, 60.9% versus 22.8%, P < 0.001), durable clinical benefit (DCB, 71.4% versus 31.6%, P < 0.001), and progression-free survival (PFS, hazard ratio = 0.46 [95% confidence interval, 0.25 to 0.82], P = 0.008). In the validation cohort (n = 1395), significant overall survival (OS) benefit was detected in the TET1-MUT patients compared to TET1-WT patients (hazard ratio = 0.47 [95% confidence interval, 0.25 to 0.88], P = 0.019), which was, importantly, independent of tumor mutational burden and high microsatellite instability; as well as not attributed to the prognostic impact of TET1-MUT (P > 0.05 in both two non-ICI-treated cohorts). In TCGA dataset, TET1-MUT was strongly associated with higher tumor mutational burden and neoantigen load, and inflamed pattern of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, immune signatures and immune-related gene expressions.

Conclusions

TET1-MUT was strongly associated with higher ORR, better DCB, longer PFS, and improved OS in patients receiving ICI treatment, suggesting that TET1-MUT is a novel predictive biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade across multiple cancer types.

Keywords: Biomarker, DNA methylation, Immune checkpoint blockade, Pan-cancer, TET1

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) or the programmed cell death (ligand) 1 [PD-(L)1] pathway have achieved impressive success in the treatment of different cancer types [1]. However, clinical responses vary, and biomarkers predictive of response may help to identify patients who will derive the greatest therapeutic benefit [2].

PD-L1 expression, high microsatellite instability (MSI-H), tumor mutational burden (TMB), T cell-inflamed gene expression profile (GEP), and specific mutated genes were reported to exhibit predictive utility in identifying responders to ICI treatment [1, 3–7]. However, only PD-L1 and MSI-H have been clinically validated hitherto [2]. Therefore, more predictive biomarkers are in urgent need.

Growing evidence points to a link between DNA methylation and anti-tumor immunity/immunotherapy [8–10]. For instance, changes in DNA methylation level have been found to correlate with the degree of immune infiltration of the tumor [11]; and DNA methylation signature was recently reported to be associated with the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [12]. However, to date, clinical evidence on the association of genomic alterations in DNA methylation-related genes and ICI response are lacking.

In this study, we systematically collected and consolidated a large amount of genomic and clinical data to evaluate the predictive function of mutations in key genes involving in the regulation of DNA methylation [13, 14]. And we found that mutations in TET1, a DNA demethylase, was predictive of higher objective response rate (ORR), better durable clinical benefit (DCB), longer progression-free survival (PFS) and improved overall survival (OS) to ICI treatment.

Methods

Pan-cancer alteration frequency analysis

For determination of the alteration frequency of TET1 among cancer types, all the genomic data from the curated set of non-redundant studies on the cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org) [15, 16] were collected and processed as shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. Tumors with nonsynonymous somatic mutations in the coding region of TET1 was defined as TET1-mutant (TET1-MUT), while tumors without as TET1-wildtype (TET1-WT) [7].

Clinical cohort consolidation

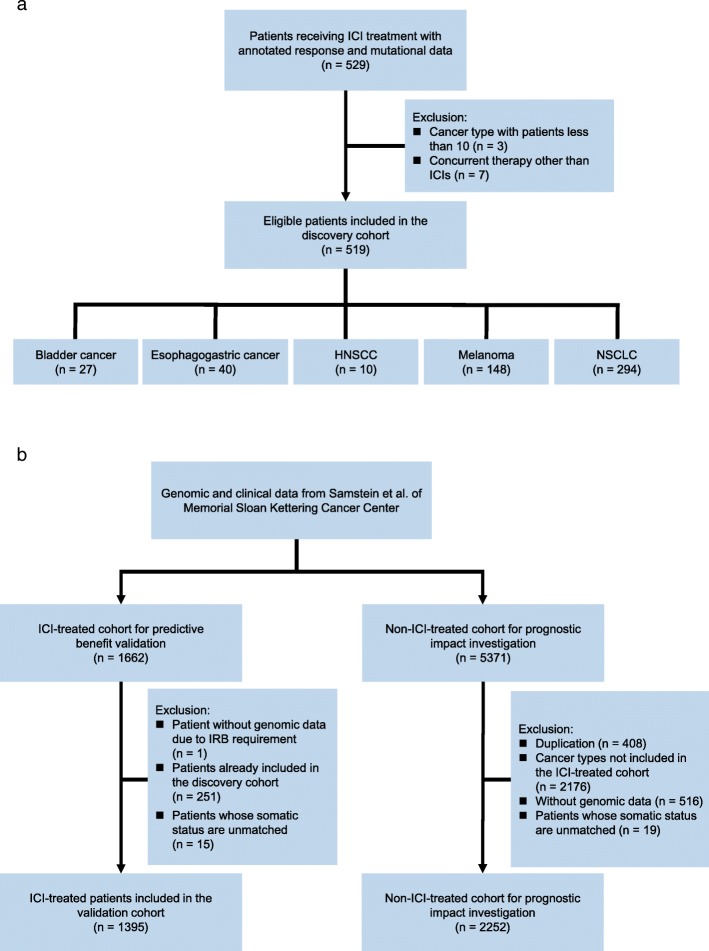

To evaluate the predictive function of specific mutated genes to ICI treatment, a discovery cohort with annotated response and mutational data of patients receiving ICI treatment from six published studies [17–22] was collected and consolidated (Fig. 1a). Samples of the first two cohorts [17, 18] (n = 280) were sequenced using MSK-IMPACT panel, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized comprehensive genomic profiling panel. While whole-exome sequencing (WES) was applied to samples of the latter four cohorts [19–22] (n = 249), which were previously curated and filtered by excluding records without response data and records without qualified mutational data by Miao et al. [22]. Based on Miao et al.’s efforts, we further excluded records of cancer type with patients less than 10 (n = 3) and patients receiving concurrent therapy besides ICIs (n = 7). In the end, 519 patients from five cancer types were included in the discovery cohort. An expanded ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al. [23] without response data but with survival data was used as the validation cohort to further validated the predictive function of TET1-MUT to ICI treatment (Fig. 1b). The non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al. [23] was also included to investigate the possibility that the observed survival differences among patients with TET1-MUT and TET1-WT might simply be attributable to a general prognostic benefit of TET1-MUT, unrelated to ICIs. As the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al. mainly consisted of patients with advanced disease, the Cancer Genome Altas (TCGA) cohort consisting of 20 cancer types with adequate survival information as determined by Liu et al. [24] was additionally employed to investigate the prognostic impact of TET1-MUT.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the clinical cohort consolidation. a. Consolidation of the discovery cohort from six published studies. b. Consolidation of the validation cohort and the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; IRB, Institutional Review Board

TMB normalization in the clinical cohorts

TMB was defined as the total number of nonsynonymous somatic, coding, base substitution, and indel mutations per megabase (Mb) of genome examined [25]. For samples sequenced by WES, the total number of nonsynonymous mutations were normalized by megabases covered at adequate depth to detect variants with 80% power using MuTect given estimated tumor purity, as determined by Miao et al. [22]. For samples sequenced by MSK-IMPACT panel, the total number of nonsynonymous mutations identified was normalized to the exonic coverage of the MSK-IMPACT panel (0.98, 1.06, and 1.22 Mb in the 341-, 410-, and 468-gene panels, respectively), and mutations in driver oncogenes were not excluded from the analysis as Samstein et al. proposed [23]. As previously described, the cutoff of the top 20% within each histology was used to divided patients into TMB-high and TMB-low groups [23].

Clinical outcomes

The primary clinical outcomes were ORR, DCB, PFS, and OS. ORR was assessed using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. DCB was classified as durable clinical benefit (DCB; complete response [CR]/partial response [PR] or stable disease [SD] that lasted > 6 months) or no durable benefit (NDB, progression of disease [PD] or SD that lasted ≤6 months) [18]. Patients who had not progressed and were censored before 6 months of follow-up were considered not evaluable (NE). PFS was assessed from the date the patient began immunotherapy to the date of progression or death of any cause. Patients who had not progressed were censored at the date of their last scan. In the discovery cohort and validation cohort, OS was calculated from the start date of ICI treatment, and patients who did not die were censored at the date of last contact. Notably, in the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al., OS was calculated from the date of first infusional chemotherapy, while in the TCGA cohort, OS was calculated from the date of first diagnosis.

Tumor immunogenicity and anti-tumor immunity analysis

To characterize the tumor immune microenvironment of TET1-MUT tumors, we further compared the TMB, neoantigen load, tumor-infiltrating leukocytes, immune signatures and immune-related gene expressions between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors in the TCGA dataset. Somatic mutational data from Ellrott et al. [26], neoantigen data from Thorsson et al. [27], and RNA-seq data from UCSC Xena data portal (https://xenabrowser.net) were collected and processed as shown in Additional file 2: Figure S2. TMB was retained as the total number of somatic nonsynonymous mutation count without normalization, and neoantigen load was defined as the total predicted neoantigen count as determined by Thorsson et al. [27]. The R package MCP-counter was used to estimate the abundance of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes [28]. Seven classical immune signatures were adopted from Rooney et al. [29], and the R package GSVA was used to determine the single sample gene set enrichment (ssGSEA) scores of each immune signature [30]. Immune-related genes and their functional classification were obtained from Thorsson et al. [27], whose expression level was quantified as FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments) and log2-transformed.

Statistical analysis

Assessment of enrichment of specific mutated genes with response (CR/PR versus PD/SD) was done with fisher’s exact test and the P values were controlled for false discovery rate (FDR). The association between TET1 status and ORR or DCB were examined using fisher’s exact test. The progression-free and overall survival probability of TET1-MUT and TET1-WT patients were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank test, and Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, which were adjusted for available confounding factors, including 1) age, sex, cancer type, and TMB in the discovery cohort; 2) age, sex, cancer type, TMB status, and MSI status in the validation cohort; 3) sex, cancer type, TMB status in the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al.; and 4) age, sex, ethnicity, cancer type, histology grade, tumor stage, TMB, and year of first diagnosis in the TCGA cohort. Interactions between the TET1 status and the following factors were assessed, including age (≤ 60 versus > 60 years), sex (male versus female), cancer type (melanoma, bladder cancer, NSCLC versus other cancers), TMB status (low versus high) and drug class (monotherapy versus combination therapy). The differences of TMB, neoantigen load, tumor-infiltrating leukocytes, immune signatures, or immune-related gene expressions between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors were examined using Mann-Whitney U test. The nominal level of significance was set at 0.05 and all statistical tests were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using R v. 3.5.2 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

TET1-MUT was enriched in patients responding to ICI treatment

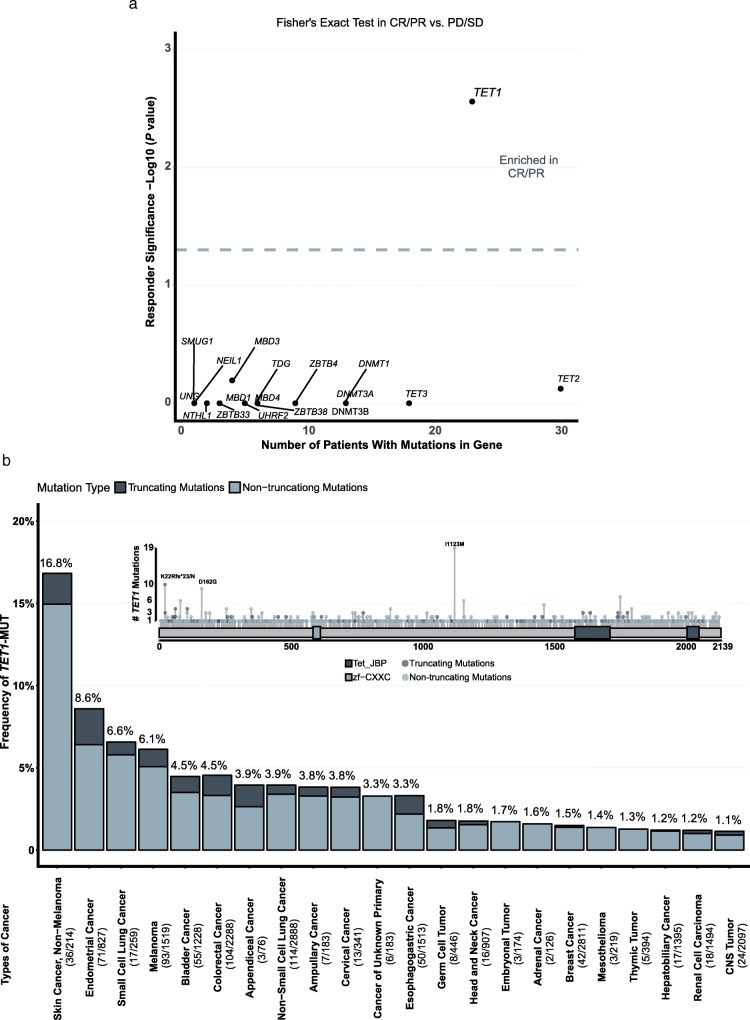

As shown in Fig. 1a, mutational data with annotated response data were pooled from six publicly available studies to form the discovery cohort, which included 519 patients across five cancer types: bladder cancer (n = 27), esophagogastric cancer (n = 40), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (n = 10), melanoma (n = 148), and NSCLC (n = 294). Patient characteristics of the discovery cohort were summarized in Table 1. Particularly, more than half (61.7%) of patients were treated with PD-(L)1 monotherapy, representing its predominant role in immunotherapy. Twenty-one key genes involving in the regulation of DNA methylation, including DNA methyltransferase DNMT1, DNMT3A, DMNT3B, and DNA demethylase TET1, TET2, TET3, and other mediators, were manually collected from previous studies [13, 14] (Additional file 3: Table S1) and investigated. Within these genes, TET1-MUT was significantly enriched in patients responding to ICI treatment (Fig 2a) (P = 0.003), indicating that TET1-MUT may be a potential predictive biomarker for ICI treatment.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of the discovery cohort

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 519 |

| Median age, years (range) | 64 (18–92) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 300 (57.8) |

| Female | 219 (42.2) |

| Cancer type | |

| Bladder cancer | 27 (5.2) |

| Esophagogastric cancer | 40 (7.7) |

| Head and neck cancer | 10 (1.9) |

| Melanoma | 148 (28.5) |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | 294 (56.6) |

| Drug class | |

| CTLA-4, monotherapy | 142 (27.4) |

| PD-(L)1, monotherapy | 320 (61.7) |

| CTLA-4 + PD-(L)1, combination therapy | 57 (11.0) |

| Best overall response | |

| CR/PR | 126 (24.3) |

| SD | 137 (26.4) |

| PD | 252 (48.6) |

| NE | 4 (0.8) |

| Durable clinical benefit | |

| DCB | 165 (31.8) |

| NDB | 330 (63.6) |

| NE | 24 (4.6) |

| Median TMB, Mutation/Mb (IQR) | 7.14 (3.77–13.24) |

| TET1 status | |

| Mutant | 23 (4.4) |

| Wildtype | 496 (95.6) |

Abbreviations: CR complete response, CTLA-4 cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-4, DCB durable clinical benefit, IQR interquartile range, Mb megabase, NDB no durable benefit, NE not evaluable, PD progressive disease, PD-(L)1 programmed cell death-1 or programmed death-ligand 1, PR partial response, SD stable disease, TMB tumor mutational burden

Fig. 2.

TET1-MUT was enriched in patients responding to ICI treatment. a. Response-associated mutations in CR/PR versus PD/SD (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, n = 126 patients with CR/PR, n = 389 patients with PD/SD). The dashed grey line indicated false discovery rate adjusted P = 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test). b. The proportion of TET1-MUT tumors identified for each cancer type with alteration frequency above 1%. Numbers above the barplot indicated the alteration frequency, numbers close to cancer names indicated the number of TET1-MUT patients and the total number of patients. ‘CNS tumor’ denoted tumor in the central nervous system. ‘Truncating mutations’ included nonsense, nonstop, splice site mutations, and frameshift insertion and deletion; ‘non-truncating mutations’ included missense mutations and inframe insertion and deletion

There were 23 TET1-MUT patients, accounting for 4.4% of the population in the discovery cohort (Table 1). We further investigated the alteration frequency of TET1 across multiple cancer types with genomic data collected from cBioportal. After data assembling, 32,568 patients from 39 cancer types were included in the analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The somatic mutations of TET1 were evenly distributed (Fig. 2b), without any annotated functional hotspot mutations from 3D Hotspots [31] (https://www.3dhotspots.org). The average alteration frequency of TET1 was 2.4% among these 39 cancer types, 22 of which had an alteration frequency above 1%. Skin, lung, gastrointestinal tract and urogenital system were among the most frequently affected organs (Fig. 2b).

Association of TET1 status and clinical outcomes in the discovery cohort

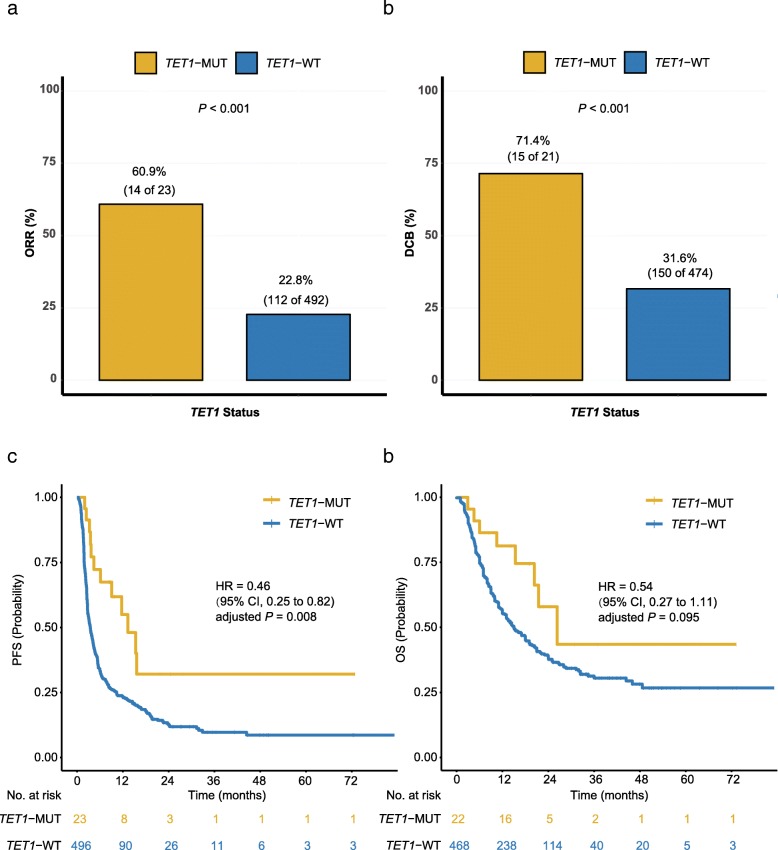

The baseline patient characteristics according to TET1 status were shown in Additional file 4: Table S2, and no significant differences were observed between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT patients except for TMB. According to RECIST version 1.1, the best overall response of four patients was not evaluable. In the remaining 515 patients, 23 patients were TET1-MUT while 492 patients were TET1-WT. The ORR of patients with TET1-MUT was more than 2.5-fold higher than that of patients with TET1-WT (Fig. 3a, 60.9% versus 22.8%, odds ratio = 5.26 [95% confidence interval (CI), 2.06 to 14.16], P < 0.001). As for DCB, 71.4% (15/21) of patients with TET1-MUT derived DCB from ICI treatment; while only 31.6% (150/474) of patients with TET1-WT did (Fig. 3b, odds ratio = 5.38 [95% CI, 1.93 to 17.27], P < 0.001). As expected, longer PFS, adjusted by age, sex, cancer type and TMB, of patients with TET1-MUT was observed (Fig. 3c, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.46 [95% CI, 0.25 to 0.82], adjusted P = 0.008). The median PFS was 13.32 months (95% CI, 9.10 to not reached) in the TET1-MUT group versus 3.49 months (95% CI, 2.99 to 4.05) in the TET1-WT group. The OS benefit from ICI treatment was also more prominent in the TET1-MUT group than that in the TET1-WT group (Fig. 3d, median OS, 26.4 months [95% CI, 20.3 to not reached] in the TET1-MUT group versus 15.0 months [95% CI, 13.0 to 18.2] in the TET1-WT group). However, after adjusted for age, sex, cancer type, and TMB, there was only numerically significant OS benefit (HR = 0.54 [95% CI, 0.27 to 1.11], adjusted P = 0.095), probably due to the limited sample size of the TET1-MUT group (n = 22).

Fig. 3.

Association of TET1 status and clinical outcomes in the discovery cohort. a. Histogram depicting proportions of patients achieved objective response (ORR) in TET1-MUT and TET1-WT groups. (n = 515; 4 patients with best overall response not evaluable). b. Histogram depicting proportions of patients derived durable clinical benefit (DCB) in TET1-MUT and TET1-WT groups. (n = 495; 24 patients with durable clinical benefit not evaluable). c. Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival (PFS) in the discovery cohort comparing patients with TET1-MUT with their respective WT counterparts. (n = 519). d. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (OS) in the discovery cohort comparing patients with TET1-MUT with their respective WT counterparts. (n = 490; 29 patients with no OS information available)

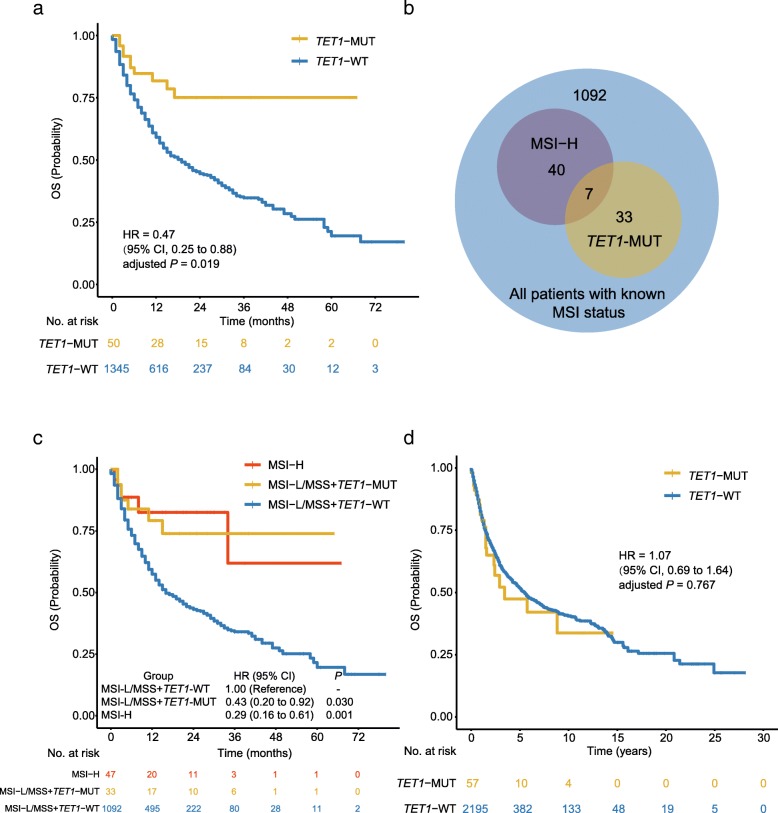

Validation of the predictive function of TET1-MUT

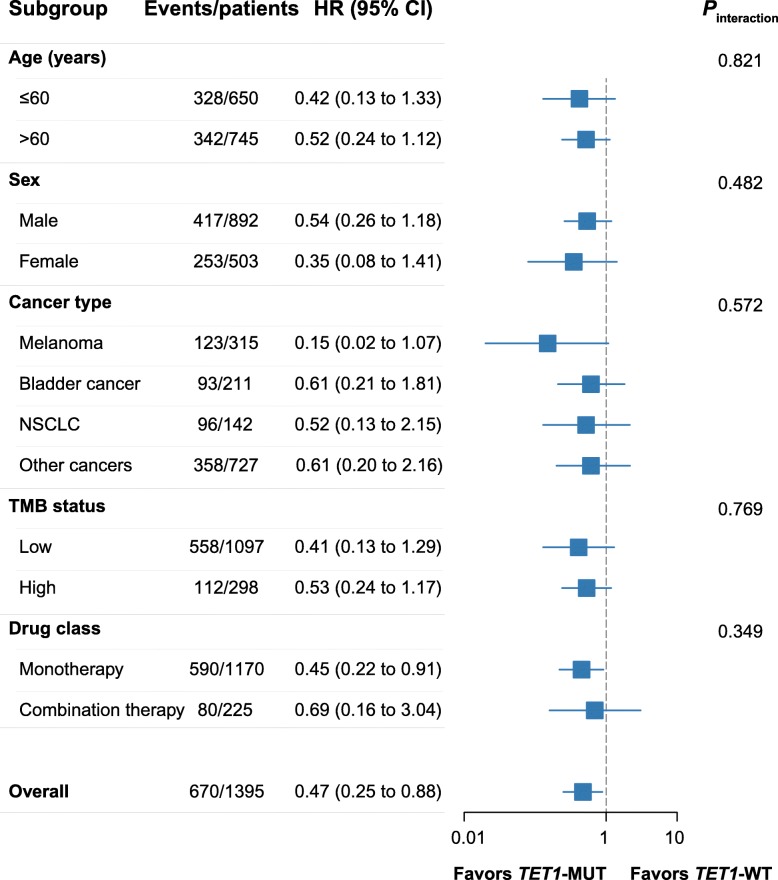

To further validate the predictive function of TET1-MUT on OS benefit, an expanded ICI-treated cohort (n = 1395) was gathered (Fig. 1b). In this validation cohort, the OS benefit was still more prominent in the TET1-MUT group than that in the TET1-WT group (Fig. 4a, the median OS was not reached in the TET1-MUT group versus 19.0 months [95% CI, 16.0 to 22.0] in the TET1-WT group). Even after adjusted for confounding factors, including age, sex, cancer type, MSI status and TMB status, TET1-MUT still independently predicted favorable OS outcomes (Fig. 4a, HR = 0.47 [95% CI, 0.25 to 0.88], adjusted P = 0.019). In patients with known MSI status (n = 1172), 47 of them were MSI-H while 40 were TET1-MUT, and only 7 patients were both MSI-H and TET1-MUT (Fig. 4b). Notably, in patients with low microsatellite instability (MSI-L) or microsatellite stable (MSS), TET1-MUT could still identify patients whose OS was significantly longer than that of TET1-WT patients (Fig. 4c, HR = 0.43 [95% CI, 0.20 to 0.92], adjusted P = 0.030), and nearly equal to that of MSI-H patients (Fig. 4c), indicating that TET1-MUT was compatible and comparable with MSI-H as predictive biomarkers. The favorable clinical outcomes for TET1-MUT versus TET1-WT were also prominent and consistent across subgroups of age, sex, cancer type, TMB status and drug class (Fig. 5, all Pinteraction > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Validation of the predictive function of TET1-MUT. a. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival (OS) of patients with TET1-MUT and patients with TET1-WT in the validation cohort. b. Venn diagram showing the concomitant presence of MSI-H and TET1-MUT within patients with known MSI status of the validation cohort. c. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the OS in the MSI-H, MSI-L/MSS and TET1-MUT, and MSI-L/MSS and TET1-WT groups in the validation cohort. d. Kaplan-Meier curves investigating the prognostic impact of TET1-MUT in the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al.

Fig. 5.

Stratification analysis in subgroups of age, sex, cancer type, TMB status and drug class in the validation cohort. Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, esophagogastric cancer, glioma, head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma and cancer of unknown primary were combined into ‘other cancers’ as the TET1-MUT cases or deaths were insufficient for hazard ratio calculation in each single cancer type. ‘Monotherapy’ indicated monotherapy of CTLA-4, PD-1 or PD-L1 antibody; ‘combination therapy’ indicated combination therapy of CTLA-4 with PD-(L)1 antibodies

To confirm that the OS benefit from ICI treatment in patients with TET1-MUT was not simply attributed to its general prognostic impact, we further evaluated the survival differences between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT patients in two non-ICI-treated cohorts. Survival difference was observed between patients with TET1-MUT and patients with TET1-WT neither in the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al. (Fig. 4d, n = 2252, HR = 1.07 [95% CI, 0.69 to 1.64], adjusted P = 0.767), nor in the TCGA cohort (Additional file 5: Figure S3, n = 6035, HR = 1.14 [95% CI, 0.91 to 1.42], adjusted P = 0.261).

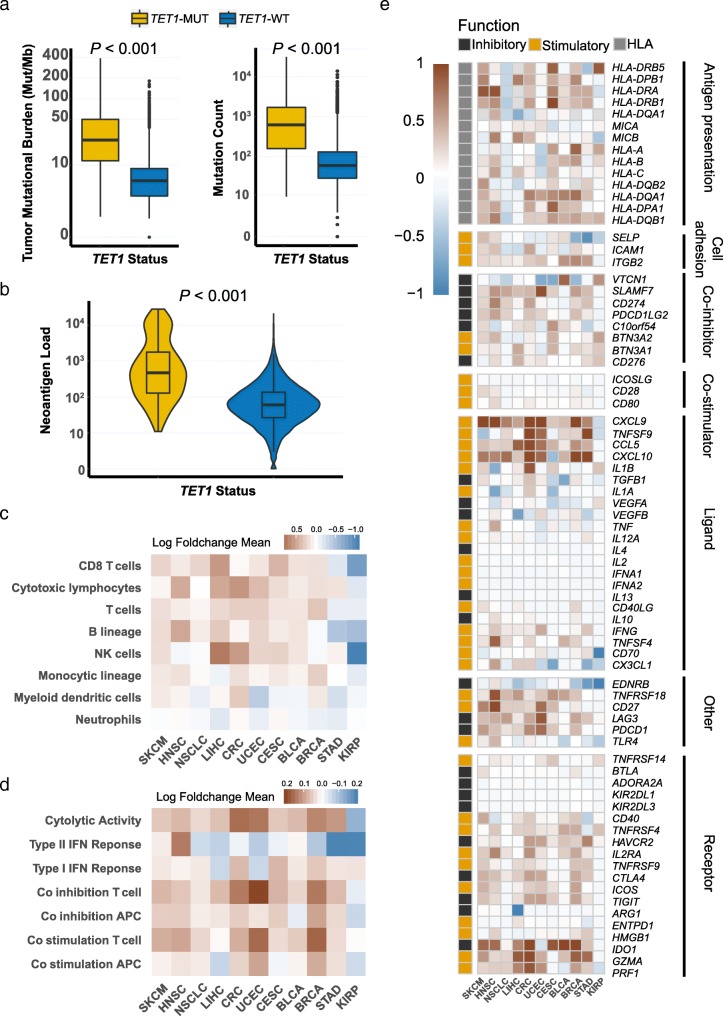

Association of TET1-MUT with enhanced immunogenicity and activated anti-tumor immunity

To characterize the tumor immune microenvironment of TET1-MUT tumors, we compared the tumor immunogenicity and anti-tumor immunity between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors. The TMB level was significantly higher in TET1-MUT tumors compared with that in the TET1-WT tumors, both in the Samstein’s cohort (Fig. 6a, left panel, P < 0.001) and in the TCGA cohort (Fig. 6a, right panel, P < 0.001). Accordantly, the neoantigen load was also significantly higher in TET1-MUT tumors (Fig. 6b, P < 0.001), indicating that TET1-MUT was associated with enhanced tumor immunogenicity.

Fig. 6.

TET1-MUT was associated with enhanced tumor immunogenicity and activated anti-tumor immunity. a. Comparison of tumor mutational burden between the TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors in the Samstein’s cohort (left panel) and the TCGA cohort (right panel). b. Comparison of neoantigen load between the TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors in the TCGA cohort. c. Heatmap depicting the log2-transformed fold change in the mean tumor-infiltrating leukocytes MCP-counter scores of the TET1-MUT tumors compared to TET1-WT tumors across different cancer types. d. Heatmap depicting the log2-transformed fold change in the mean immune signature ssGSEA scores of the TET1-MUT tumors compared to TET1-WT tumors across different cancer types. e. Heatmap depicting the mean differences in immune-related gene mRNA expressions between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors across different cancer types. The x-axis of the heatmap indicated different cancer types and the y-axis indicated tumor-infiltrating leukocytes, immune signatures, or gene names. Each square represented the fold change or difference of each indicated tumor-infiltrating leukocyte, immune signature, or immune-related gene between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors in each cancer type. Red indicated up-regulation while blue indicated down-regulation

On the other hand, the tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, especially cytotoxic lymphocytes, were generally more abundant in the TET1-MUT tumors compared with those in the TET1-WT tumors across multiple cancer types (Fig. 6c, Additional file 6: Figure S4). Besides, the results of the immune signature analysis showed that cytolytic activity signal was also significantly higher in the TET1-MUT tumors, along with general upregulation of modulatory signals, including co-inhibitory and co-stimulatory factors on antigen-presenting cells and T cell (Fig. 6d). To better characterize the immune profile, we also thoroughly examined the differences in the immune-related genes expression pattern between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors (Fig. 6e). In line with immune infiltration and signatures, many stimulatory immunomodulators were generally upregulated in the TET1-MUT tumors, such as chemokines (CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL5) and cytolytic activity associated genes (PRF1, GZMA) (Additional file 7: Figure S5). Immune checkpoints, such as CTLA4, LAG3, and TIGIT, were also upregulated in TET1-MUT tumors against TET1-WT tumors.

These results indicated that TET1-MUT was strongly associated with enhanced tumor immunogenicity and relatively hot immune microenvironment, which firmly supported its predictive function to ICI treatment.

Discussion

In this study based on carefully collected and curated genomic and clinical data, we observed that TET1-MUT was enriched in patients responding to ICIs and strongly predicted clinical benefit across multiple cancer types. TET1-MUT was found to be significantly associated with enhanced tumor immunogenicity and inflamed anti-tumor immunity. Notably, the predictive function of TET1-MUT was independent of TMB and MSI status, and also not attributed to its prognostic impact.

Although evidence concerning the association between DNA methylation and anti-immunity/immunotherapy is mounting [10–12], no clinical data regarding the correlation between genomic alterations of DNA methylation-related genes and response to ICIs are available. This study represents the first comprehensive report to examine the association between ICI response and specific mutated genes involving in the regulation of DNA methylation. Among 21 DNA methylation-related genes examined, TET1 was found to be strongly associated with higher ORR, better DCB, longer PFS, and improved OS. These findings from real-world ICI-treated cohorts added great values to the robust link between DNA methylation and immunotherapy, and firmly supported the combination strategy of immunotherapy and epigenetic therapy [8].

Although the predictive value of TET1-MUT is remarkable, one may concern that its average occurrence frequency is relatively low (2.4%). However, its scope of application falls in a pan-cancer setting like MSI-H, thus there would still be substantial patients with TET1-MUT who are most likely to derive clinical benefit from ICI treatment. To date, MSI-H is the only pan-cancer biomarker approved by the FDA [4]. The pan-cancer occurrence frequency of MSI-H is about 4% [32]; but it is clustered in endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, and gastric cancer while rarely detected in other cancers [33]. TET1-MUT is also more frequently detected in endometrial cancer and gastrointestinal cancer, as well as lung and skin cancers (Fig. 2b). On the other hand, the ORR in TET1-MUT patients is 60.9% (95% CI, 50.0 to 80.8%), which is numerically higher than that in MSI-H patients (about 32% ~ 55%) [34–37]; while no survival difference was observed between MSI-H and TET1-MUT patients (Fig. 4c). To sum up, the alteration frequency and predictive function of TET1-MUT are comparable to MSI-H. As TET1-MUT and MSI-H are not substantially overlapped (Fig. 4b), TET1-MUT is potential to serve as another pan-cancer biomarker to ICI response in addition to MSI-H.

TMB, PD-L1 expression, and T-cell inflamed GEP were all previously shown to be associated with clinical benefit in patients treated with ICIs [1, 3, 5, 6]. However, all of these three biomarkers are continuous variables without clearly defined cut points below which response does not occur and above which response is guaranteed [38]. And TMB and PD-L1 expression both vary largely among different detecting platforms and methods [39, 40]. In contrast, TET1-MUT is easily detected with next-generation sequencing assays, and its presence in the current analysis was strongly associated with ICI response. Therefore, prospective basket trial incorporating TET1-MUT as the biomarker is worth consideration. We plan to validate these findings prospectively in an upcoming randomized phase II study of a PD-1 antibody in multiple cancer types.

This retrospective analysis also has several limitations. Only five (DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, TET1, TET2) out of the 21 DNA methylation-related genes are included in the MSK-IMPACT panel (Additional file 3: Table S1; NTHL1 is only included in the 468-gene version). Consequently, the rest of genes could only be tested in part of the discovery cohort with WES data, of which the sample size is limited (n = 239). Thus we should not totally exclude the predictive function of these genes. Besides, although TET1-MUT was found to be strongly correlated with enhanced tumor immunogenicity and inflamed anti-tumor immunity, the underlying molecular mechanism of TET1-MUT sensitizing patients to ICI treatment still requires further exploration. Further elucidation of the molecular mechanism between TET1-MUT and ICI response would also help to make the combination strategy of epigenetic therapy and immunotherapy more precise.

Conclusion

Our study provided solid evidence that TET1-MUT was associated with higher objective response rate, better durable clinical benefit, longer progression-free survival, and improved overall survival in patients receiving ICI treatment. Therefore, TET1-MUT can act as a novel predictive biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade across multiple cancer types. Further exploration of molecular mechanism and prospective clinical trials are warranted.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Related to Fig. 2B_Flowchart of data processing for the pan-cancer alteration frequency analysis of TET1. (PDF 107 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Related to Fig. 6_Flowchart of data processing of the TCGA dataset. (PDF 107 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S1. Related to Fig. 2A_Key genes involving in the regulation of DNA methylation. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S2. Related to Fig. 3_ Patient characteristics between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT subgroups of the discovery cohort. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 5: Figure S3. Related to Fig. 4_Kaplan-Meier curves investigating the prognostic impact of TET1-MUT in the TCGA cohort. (PDF 471 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S4. Related to Fig. 6C_The differences of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors. (Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (PDF 893 kb)

Additional file 7: Figure S5. Related to Fig. 6E_ The expression levels of immune-related genes, such as chemokines (A), cytolytic activity associated genes (B) and immune checkpoints (C) in TET1-MUT tumors versus TET1-WT tumors. (Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (PDF 527 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Luc G. T. Morris from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for generously sharing the clinical data of the non-ICI-treated cohort from Samstein et al.; and the staff members of the TCGA Research Network, the cBioportal, and the UCSC Xena data portal; as well as all the authors for making their valuable research data public.

Abbreviations

- BLCA

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA

Breast cancer

- CESC

Cervical squamous-cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CI

Confidence interval

- CR

Complete response

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4

- DCB

Durable clinical benefit

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FPKM

Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments

- GEP

Gene expression profile

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- KIRP

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- LIHC

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- Mb

Megabase

- MSI-H

high microsatellite instability

- MSI-L

low microsatellite instability

- MSS

microsatellite stable

- NDB

No durable benefit

- NE

Not evaluable

- NSCLC

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progression of disease

- PD-(L)1

Programmed cell death (ligand) 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- SD

Stable disease

- SKCM

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- ssGSEA

Single sample gene set enrichment

- STAD

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TET1-MUT

TET1-mutant

- TET1-WT

TET1-wildtype

- TMB

Tumor mutational burden

- UCEC

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: RX, FW, HW, and QZ. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Study supervision: RX and FW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1313300); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2017A030313485, 2014A030312015); the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (2019B020227002).

Availability of data and materials

All of the data we used in this study were publicly available as described in the Method section.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was waived since we used only publicly available data and materials in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hao-Xiang Wu, Yan-Xing Chen and Zi-Xian Wang contributed equally to this work.

Feng Wang and Rui-Hua Xu are joint senior authors.

Contributor Information

Feng Wang, Phone: +86-20-8734 3795, Email: wangfeng@sysucc.org.cn.

Rui-Hua Xu, Phone: +86-20-8734 3333, Email: xurh@sysucc.org.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s40425-019-0737-3.

References

- 1.Havel JJ, Chowell D, Chan TA. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(3):133–150. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cristescu Razvan, Mogg Robin, Ayers Mark, Albright Andrew, Murphy Erin, Yearley Jennifer, Sher Xinwei, Liu Xiao Qiao, Lu Hongchao, Nebozhyn Michael, Zhang Chunsheng, Lunceford Jared K., Joe Andrew, Cheng Jonathan, Webber Andrea L., Ibrahim Nageatte, Plimack Elizabeth R., Ott Patrick A., Seiwert Tanguy Y., Ribas Antoni, McClanahan Terrill K., Tomassini Joanne E., Loboda Andrey, Kaufman David. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade–based immunotherapy. Science. 2018;362(6411):eaar3593. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott PA, Bang YJ, Piha-Paul SA, Razak ARA, Bennouna J, Soria JC, et al. T-cell-inflamed gene-expression profile, programmed death ligand 1 expression, and tumor mutational burden predict efficacy in patients treated with Pembrolizumab across 20 cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4):318–327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus L, Lemery SJ, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(13):3753–3758. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in lung Cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riaz N, Havel JJ. Recurrent SERPINB3 and SERPINB4 mutations in patients who respond to anti-CTLA4 immunotherapy. Nature genetics. 2016;48(11):1327–1329. doi: 10.1038/ng.3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiappinelli KB, Zahnow CA, Ahuja N, Baylin SB. Combining epigenetic and immunotherapy to combat Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76(7):1683–1689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn J, Rao S. Epigenetics and immunotherapy: the current state of play. Mol Immunol. 2017;87:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PA, Ohtani H, Chakravarthy A, De Carvalho DD. Epigenetic therapy in immune-oncology. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2019;19(3):151–161. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedeurwaerder S, Desmedt C, Calonne E, Singhal SK, Haibe-Kains B, Defrance M, et al. DNA methylation profiling reveals a predominant immune component in breast cancers. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3(12):726–741. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duruisseaux M, Martinez-Cardus A, Calleja-Cervantes ME, Moran S, Castro de Moura M, Davalos V, et al. Epigenetic prediction of response to anti-PD-1 treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(10):771–781. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng H, Cao Y, Qin J, Song X, Zhang Q, Shi Y, et al. DNA methylation, its mediators and genome integrity. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11(5):604–617. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.11218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(3):204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janjigian YY, Sanchez-Vega F, Jonsson P, Chatila WK, Hechtman JF, Ku GY, et al. Genetic predictors of response to systemic therapy in Esophagogastric Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(1):49–58. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizvi H, Sanchez-Vega F, La K, Chatila W, Jonsson P, Halpenny D, et al. Molecular determinants of response to anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 and anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung Cancer profiled with targeted next-generation sequencing. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7):633–641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350(6257):207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao D, Margolis CA. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade in microsatellite-stable solid tumors. Nature genetics. 2018;50(9):1271–1281. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nature genetics. 2019;51(2):202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, Poisson LM, Lazar AJ, Cherniack AD, et al. An integrated TCGA pan-Cancer clinical data resource to drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell. 2018;173(2):400–16.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(25):2500–2501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellrott K, Bailey MH, Saksena G, Covington KR, Kandoth C, Stewart C, et al. Scalable Open Science approach for mutation calling of tumor exomes using multiple genomic pipelines. Cell Syst. 2018;6(3):271–81.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D, Bortone DS, Ou Yang TH, et al. The immune landscape of Cancer. Immunity. 2018;48(4):812–30.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becht E, Giraldo NA, Lacroix L, Buttard B, Elarouci N, Petitprez F, et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao J, Chang MT, Johnsen HC, Gao SP, Sylvester BE, Sumer SO, et al. 3D clusters of somatic mutations in cancer reveal numerous rare mutations as functional targets. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hause RJ, Pritchard CC, Shendure J, Salipante SJ. Classification and characterization of microsatellite instability across 18 cancer types. Nat Med. 2016;22(11):1342–1350. doi: 10.1038/nm.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baretti M, Le DT. DNA mismatch repair in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;189:45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, Lenz HJ, Gelsomino F, Aglietta M, et al. Durable clinical benefit with Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(8):773–779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le D, Kavan P, Kim T, Burge M, Van Cutsem E, Hara H, et al. O-021Safety and antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H) colorectal cancer: KEYNOTE-164. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl_5).

- 37.Diaz Luis A., Marabelle Aurelien, Delord Jean-Pierre, Shapira-Frommer Ronnie, Geva Ravit, Peled Nir, Kim Tae Won, Andre Thierry, Van Cutsem Eric, Guimbaud Rosine, Jaeger Dirk, Elez Elena, Yoshino Takayuki, Joe Andrew K., Lam Baohoang, Gause Christine K., Pruitt Scott Knowles, Kang S. Peter, Le Dung T. Pembrolizumab therapy for microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) colorectal cancer (CRC) and non-CRC. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):3071–3071. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.3071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teo MY, Seier K, Ostrovnaya I, Regazzi AM, Kania BE, Moran MM, et al. Alterations in DNA damage response and repair genes as potential marker of clinical benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in advanced urothelial cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1685–1694. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsao MS, Kerr KM, Kockx M, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Botling J, et al. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry comparability study in real-life clinical samples: results of blueprint phase 2 project. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(9):1302–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Addeo Alfredo, Banna Giuseppe L., Weiss Glen J. Tumor Mutation Burden—From Hopes to Doubts. JAMA Oncology. 2019;5(7):934. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Related to Fig. 2B_Flowchart of data processing for the pan-cancer alteration frequency analysis of TET1. (PDF 107 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Related to Fig. 6_Flowchart of data processing of the TCGA dataset. (PDF 107 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S1. Related to Fig. 2A_Key genes involving in the regulation of DNA methylation. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S2. Related to Fig. 3_ Patient characteristics between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT subgroups of the discovery cohort. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 5: Figure S3. Related to Fig. 4_Kaplan-Meier curves investigating the prognostic impact of TET1-MUT in the TCGA cohort. (PDF 471 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S4. Related to Fig. 6C_The differences of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes between TET1-MUT and TET1-WT tumors. (Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (PDF 893 kb)

Additional file 7: Figure S5. Related to Fig. 6E_ The expression levels of immune-related genes, such as chemokines (A), cytolytic activity associated genes (B) and immune checkpoints (C) in TET1-MUT tumors versus TET1-WT tumors. (Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (PDF 527 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All of the data we used in this study were publicly available as described in the Method section.