Abstract

Corneal blindness is one of the major causes of reversible blindness, which can be managed with transplantation of a healthy donor cornea. It is the most successful organ transplantation in the human body as cornea is devoid of vasculature, minimizing the risk of graft rejection. The first successful transplant was performed by Zirm, and since then, corneal transplantation has seen significant evolution. It has been possible because of the relentless efforts by researchers and the increase in knowledge about corneal anatomy, improvement in instruments and advancements in technology. Keratoplasty has come a long way since the initial surgeries wherein the whole cornea was replaced to the present day where only the selective diseased layer can be replaced. These newer procedures maintain structural integrity and avoid catastrophic complications associated with open globe surgery. Corneal transplantation procedures are broadly classified as full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty and partial lamellar corneal surgeries which include anterior lamellar keratoplasty [sperficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty (SALK), automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty (ALTK) and deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK)] and posterior lamellar keratoplasty [Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK)] broadly.

Keywords: Corneal blindness, corneal transplantation, eye banking, graft rejection, keratoplasty, visual acuity

Introduction

Corneal transplantation or keratoplasty is the most commonly performed and also the most successful allogenic transplant worldwide. Zirm1 performed the first corneal transplantation in 1905. Since then, corneal transplantation has evolved from the replacement of full-thickness cornea to the replacement of selective diseased layers of the cornea. This has been possible because of the improvement in understanding of corneal anatomy, advanced surgical techniques, instruments and microscopes2. Organ transplantation is a complex process with multiple legal, ethical and cultural issues. The corneal tissue has several characteristics that make storage and transplantation easier and the eye bank plays an important role in the whole process of corneal retrieval, storage and transplantation.

Cornea: Structure and Function

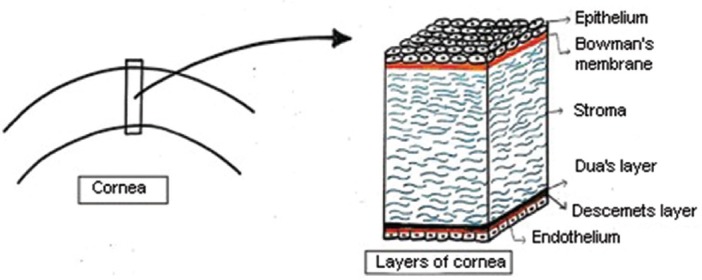

The cornea is a transparent and avascular structure of the eye, which constitutes the anterior-most part of the eyeball. It consists of six different anatomical layers (Fig. 1). The anterior-most is epithelium consisting of squamous cells, wing cells and basal cells. The second layer is Bowman's membrane, which has regenerative properties. Stroma constitutes the major part of the cornea and contains keratocytes and collagen lamellae that are densely distributed in the anterior as compared to the posterior stroma. Dua's layer is almost 10-15 μm in thickness and remains strongly adhered to overlying stromal fibres. The Descemet membrane provides a base for endothelial cells that have a key role in maintaining corneal transparency.

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of anatomical layers of the cornea (Drawn by the authors based on the theoretical knowledge of the corneal anatomy).

Corneal transplantation: Evolution and types

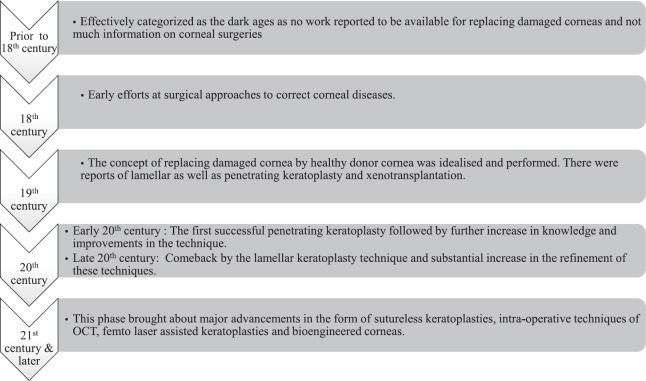

In 1813 Himly first mentioned the concept of corneal transplantation3, but Von Hippel4 actually performed the first transplant in 1886 by replacing human diseased cornea with that of rabbit cornea. Fuchs did the first lamellar keratoplasty (LK), which was not accepted well because of poor outcomes in terms of visual quality5. The first successful corneal transplant was performed by Zirm1 in 1905. Keratoplasty can be done for various purposes and is classified as therapeutic, tectonic and optical. Therapeutic keratoplasty is done to remove the infective portion of the cornea mainly in cases of recalcitrant or perforated infective keratitis. Tectonic keratoplasty provides support and maintains the integrity of the globe. Optical keratoplasty aims to restore vision and has seen various advancements with time that has led to refinement in post-operative visual quality and outcomes. In the 19th century, LK that involves removal of selective corneal layers was initially used to treat anterior corneal opacities. It was used to treat corneal scars, keratoconus but discontinued due to suboptimal visual gain, which could be attributed to irregular interface or residual opacities6. It was also associated with a longer learning curve. This led to an increase in the popularity of full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty (PKP), which provided better visual quality in that era. As full-thickness PKP was associated with its own set of problems such as risk of immune rejection, weak graft-host junction, suture-related complications such as loose sutures, suture-related infiltrates, astigmatism and longer recovery time, re-introduction of LK helped in solving many of these problems of full-thickness keratoplasty. Moffatt et al7 have described the various eras of corneal transplantation as the seven epochs depicting the major developments and advancements. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of corneal transplantation from the 17th century to the present time7.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart showing the evolution of corneal transplantation. Source: Ref. 7.

Types of corneal transplantation

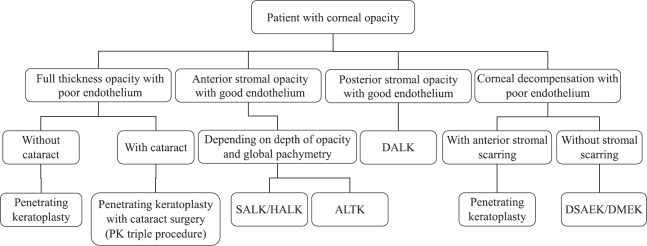

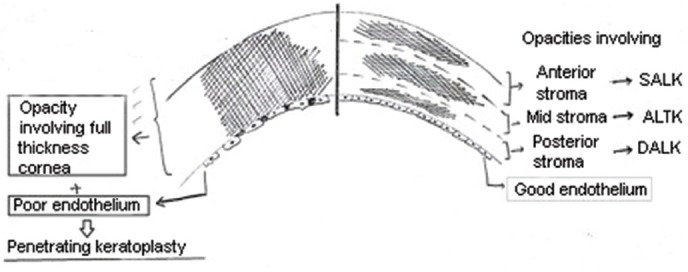

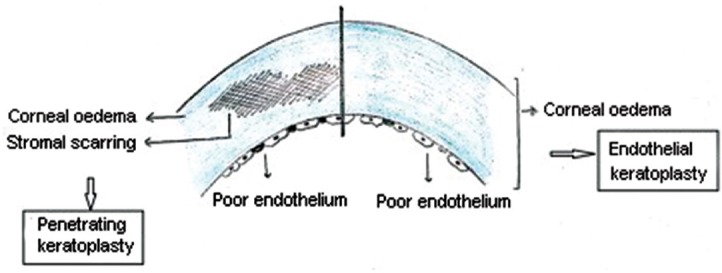

There are various anatomical and clinical parameters that need to be evaluated before planning the type of corneal transplantation. A stepwise approach may be utilized while deciding the type of keratoplasty to be used for optimal management of a patient requiring corneal transplantation (Fig. 3). Corneal transplantation can be classified on the basis of indication for which it is being done (therapeutic, tectonic and optical). Similarly, there are different techniques, which are used for replacing selective anterior or posterior diseased part of cornea with a normal donor cornea. This technique of selective replacement of diseased part has many advantages in terms of less intra-operative complications, maintaining globe integrity and less chances of graft rejection in post-operative period as lesser amount of tissue is transplanted as compared to full-thickness PKP. Corneal transplantation is thus broadly classified as full-thickness PKP, anterior and posterior LKs (PLK) (Figs 4 & 5).

Fig. 3.

Flowchart depicting a stepwise approach while planning surgical management in a case of corneal opacity. SALK, superficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty; HALK, hemi-automated lamellar keratoplasty; ALTK, automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty; DALK, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, DSAEK, Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty, DMEK, Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty.

Fig. 4.

Diagrammatic representation of the type of keratoplasty depending the on the level of corneal opacities along with endothelial function (Drawn by the authors based on the practical knowledge utilized for decision making in cases of corneal opacity). SALK, superficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty; ALTK, automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty; DALK, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty.

Fig. 5.

Diagrammatic representation of the type of keratoplasty to be chosen for cases of corneal decompensation with compromised endothelium with and without stromal scarring. (Drawn by the authors based on the practical knowledge utilized for decision making in cases of corneal decompensation).

Anterior lamellar keratoplasty (ALK)

The lost technique of ALK was brought back in 1948 by Paufique et al8. Microkeratome was introduced in 1964 by Barraquer9. He used it to treat high refractive errors by the technique of keratomileusis and keratophakia10. Microkeratome was able to give a more regular cut and thus avoid the poor visual gain because of the irregular interface. Kaufman11 modified the technique and introduced epikeratophakia, which described the use of lamellar graft without the need to perform host corneal dissection. Anterior LK has come a long way from manual dissection to microkeratome assisted and now to femtosecond laser-assisted keratoplasty. There are a variety of techniques described for anterior LK depending upon the depth of corneal opacity.

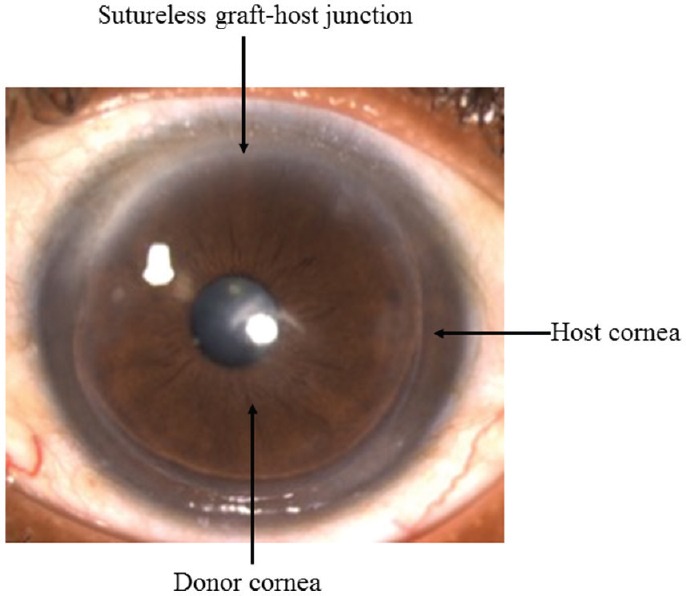

Superficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty (SALK): It was first described by Kaufman et al12 in 2003. It is used to treat corneal opacities involving anterior 30-40 per cent of the cornea. They did a sutureless surgery and replaced the host with a 200 μm lamellar graft using fibrin glue. It is mainly indicated for superficial scars as a result of healed keratitis, trachoma, trauma, superficial corneal dystrophies or degenerations13 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Post-operative clinical photograph of sutureless superficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty (SALK) for healed keratitis with superficial opacity involving anterior 200 μm of cornea. The photograph demonstrates a well apposed clear lamellar graft.

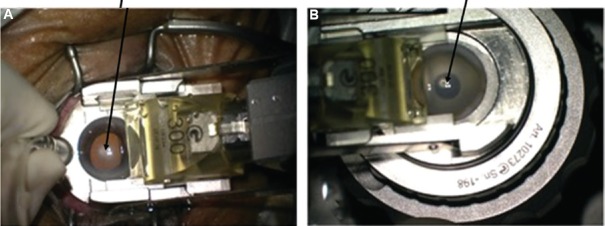

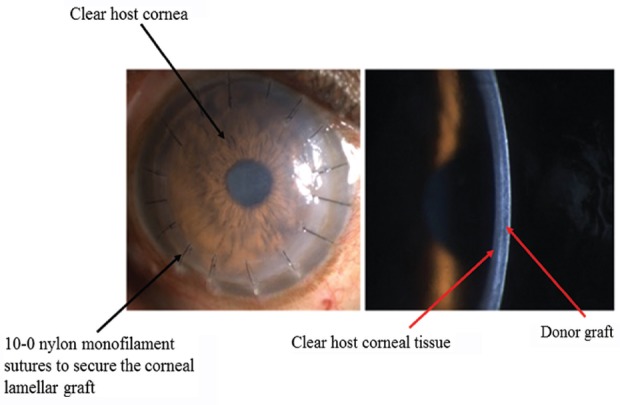

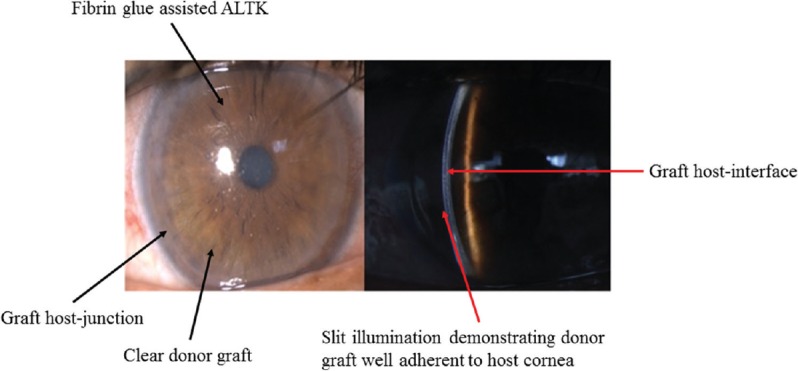

Automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty (ALTK): It is used for the treatment of anterior to midstromal corneal opacities. In this technique, the microkeratome is used to dissect both the host as well as the donor14. It thus gives a better apposition and interface regularity between the host and donor graft (Figs. 7-9).

Fig. 7.

Intra-operative pictures showing use of automated microkeratome for host dissection (A) and donor dissection (B) in case of automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty (ALTK).

Fig. 9.

Clinical pictures showing post-operative diffuse (left) and slit images (right) of automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty (with sutures). 10-0 nylon monofilament=0.020-0.029 mm thickness.

Fig. 8.

Post-operative clinical photographs of a patient operated using automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty for right eye nebulomacular opacity.

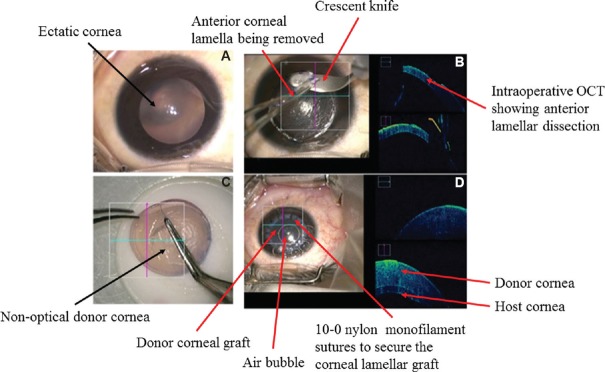

Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK): It is performed in cases of deep anterior corneal opacities with a good endothelial function. Various indications are deep stromal scars of healed keratitis, keratoconus and stromal dystrophies. It is of two types: pre-descemetic and descemetic. Pre-descemetic is done where the cornea is very thin and a high risk of perforation is expected. It aims to remove the pathology while still leaving a little posterior stroma along with intact endothelium. Descemet DALK aims to remove the complete stroma while leaving behind only bare Descemet's membrane. There are various techniques of performing DALK including manual dissection. Archila13 and Melles et al15 have described techniques for a deeper dissection using air or viscoelastic. Anwar and Teichmann16 remarkably improved the technique of deep DALK by introducing big bubble technique. Deep stromal injection of air is used to completely bare the Descemet's membrane (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Intra-operative sequential steps of manual deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty in case of advanced keratoconus. (A) Keratoconus with paracentral ectasia; (B) lamellar dissection with the aid of intra-operative optical coherence tomography; (C) donor preparation; (D) at the end of surgery intra-operative optical coherence tomography showing well-apposed donor graft to host bed. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK)

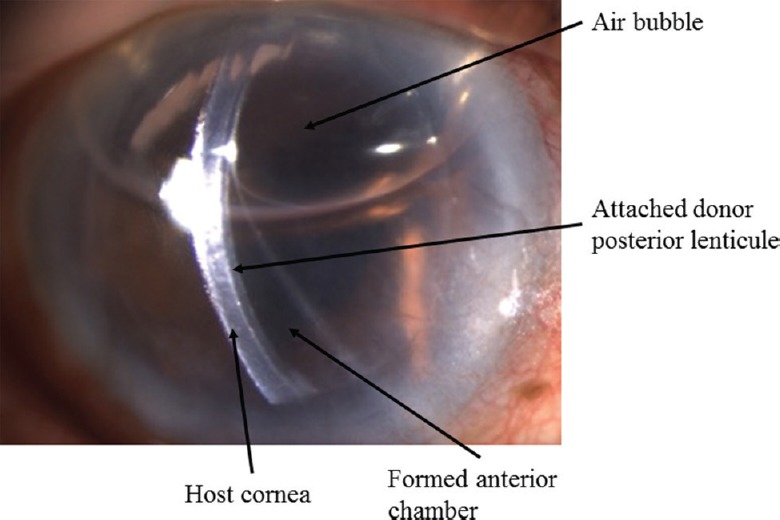

These procedures are used to replace the endothelium and treat the conditions in which only endothelium (posterior-most layer of the cornea) is diseased and the rest of the cornea is not affected, e.g., Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD), congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED), iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome, viral endothelial dysfunction, aphakic bullous keratopathy (ABK) and pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (PBK). The initial surgeons attempted to replace the posterior lamella of the cornea by doing an anterior dissection17,18, but this never became popular, and in 1956, Tillet17 introduced a posterior lamellar approach. Even though the posterior approach was used, the visual outcome and graft survival was poor which was attributed to manual dissection and use of sutures19. Melles et al20 used air as tamponade agent for graft attachment to the host cornea instead of sutures. In this technique, a posterior stromal button was retrieved from a host by lamellar dissection and replaced by donor tissue through a 9 mm limbal incision21. PLK was introduced by Melles et al20 in which the donor was folded and inserted through a 5 mm incision. The same technique was introduced as deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) in the USA by Terry and Ousley22. Melles et al23 further modified their technique and introduced Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK). They modified the concept of host stromal dissection and introduced Descemet's stripping or descemeterorrhexis. In this technique, the Descemet's membrane-endothelium complex was removed by stripping and replaced by a posterior lamellar button from the donor tissue. DSEK became Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) when Gorovoy24 used an automated microkeratome for donor tissue dissection. It made the learning curve easier as well the interface smoother and thus led to better visual outcomes. Melles et al25 again presented a breakthrough surgery in 2006 when they replaced only the diseased endothelium with a healthy endothelium by the technique of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). It involves stripping the Descemet's membrane from the donor tissue but is associated with superior visual outcomes26. EK is a better option as compared to PKP in patients with endothelial dysfunction of the cornea, as it minimizes the catastrophic intraoperative complications such as expulsive haemorrhage and choroidal detachment associated with an open globe surgery. It helps in early visual recovery with no suture-related complications and astigmatism. It is nowadays being considered as more of a refractive surgery owing to the early and better visual outcome (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Post-operative day 1 clinical picture of operated Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) showing well-apposed lenticule to host cornea.

Review of literature: Changing trends

Changing trends: Shift from full thickness to lamellar keratoplasty

Darlington et al27 did a review of corneal transplantation over a period from 1980 to 2004 and found that more than 95 per cent of corneal tissues were used for PKP, and the major indications were PBK, keratoconus, FECD and failed grafts. Röck et al28 did a study to evaluate the evolution of surgical procedures. They found that the mean rate of corneal transplantations doubled from 71 per year in the first six-year period to 139 per year in the second six-year period. Even though the number of PKP remained the same, the number of DMEK increased significantly from 2008 to 2016. It thus shows a remarkable change from full-thickness keratoplasties towards LKs. Zhang et al29 evaluated the trend of keratoplasty from 2000 to 2012, and found a significant decrease in the number of PKP and an increase in DSAEK and DALK since the introduction of lamellar keratoplasty in 2006. FECD was managed by DSAEK in 83 per cent cases and PKP in 13 per cent in 2011-2012. Le et al30 evaluated the current surgical approaches at the University of Toronto and found that 61 per cent of keratoplasties were LK and 39 per cent underwent full-thickness PKP. Amongst the lamellar procedures, DSAEK accounted for most of the surgeries (68%) followed equally by DALK (16%) and DMEK (16%). Zare et al31 during their study period of six years found the most common surgical technique to be PKP (70.9%), followed by DALK (20.1%) and DSAEK (2.3%). However, over the study period, there was a significant decrease in the number of PKP and increase in LK. Park et al32 in their 10 yr review found that there was an increase in the total number of corneal transplants from 2005 to 2014. In the last decade of their study, PKP was found to decrease significantly (from 95 to 42%) and an increase in LK techniques (from 5 to 58%) was seen. DSAEK was the most common (50%) type of corneal transplantation performed in the United States in 2014. The volume of DMEK was found to be doubling every year since 201132. About 75 per cent of cases of corneal decompensation were managed by EK in 201432. EK was the treatment of choice for more than 90 per cent cases of FECD and for 60 per cent of PBK cases; while PKP was being done for 40 per cent of cases of PBK32.

Changing trends: Indications of keratoplasty

Corneal blindness is a major health problem worldwide. The indications for corneal transplantation are different from one region to another. Bullous keratopathy has been seen to be the most common indication for transplant in developed countries whereas infective keratitis and scars are more common in developing countries. There is a changing trend being noted in developing countries as well33. Corneal diseases contributing to blindness in this region have also shifted to post-surgical bullous keratopathy (46.2%) and corneal degenerations (23.1%)33. Park et al32 evaluated the international distribution of corneal grafts from the Eye Bank Association of America (EBAA) and reported that the numbers of grafts increased from less than 1000 in 2005 to 24,400 grafts in 2014. The most common indications of corneal transplantation were PBK, keratoconus, FECD and failed grafts. PBK was the most common indication (20%) for PKP in 2005, which decreased significantly and became the third most common indication (9%) in 2014. FECD (22%) was the most common indication for corneal transplantation followed by PBK (12%), keratoconus (10%) and repeat corneal graft (10%) in 2014. There has been an increase in the number of PKP being performed for congenital opacities such as Peter's anomaly, sclerocornea, CHED and corneal dermoid. The most common indications for LK in this study were corneal degeneration, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, keratoconus and non-specific anterior lamellar stromal scarring. Keratoconus has increased significantly as an indication for LK since 2008 and is responsible for one-third cases of LK being performed32.

Röck et al28 evaluated the indications for corneal transplantation and the changing trends of corneal transplantation from 2005 to 2016. The waiting list of patients increased from 36 patients in 2005 to 246 in 2016. The most common indications were found to be FECD (45.5%) and keratoconus (14.2%). Other indications for corneal transplantation were bullous keratopathy (10.4%), trauma (4.3%) and corneal graft failure due to rejection (8.9%), followed by infective keratitis and ulcers resulting due to trophic disease or chemical and thermal burns (16.8%). In 2005, corneal transplantation was most commonly done for keratoconus (41.7%); however, in 2016, it went down to the third most common indication (6.5%) as FECD significantly rose as the most common indication for transplant since 2013 and accounted for 69.5 per cent of transplants28. Zhang et al29 reported FEC to a more common indication for transplantation as compared to PBK. Zare et al31 conducted a study in Iran over a period of six years from January 2004 to December 2009. They found keratoconus to be the most common indication for transplantation (38.4%) followed by bullous keratopathy (11.7%), failed grafts (10.6%), infective keratitis (10.1%) and trachomatous keratopathy. FECD accounted for only 0.8 per cent of transplants being done in Iran during the study period31.

According to Le et al30, the most common indication for PKP was graft failure (30%) followed by infection (18%), and keratoconus (17%). DSAEK was most commonly done for FECD (40%) and bullous keratopathy (33%). Keratoconus (57%) and corneal scarring (35%) were found to be the most common indications for DALK. DMEK was done mostly in cases of FECD (82%)30.

Post-operative outcomes in various types of keratoplasty

Endothelial keratoplasty (EK)

In DSAEK, only the posterior lamella is replaced as compared to full-thickness PKP that gives it the benefit of faster and early visual recovery34. Suture-related problems such as infiltrates, astigmatism and risk of rejection are also reduced. DSAEK is associated with a hyperopic shift of the order of approximately 0.8-1.5 D35, depending on the lenticule thickness being transplanted. Hence, the intraocular lens power needs to be refined according to this phenomenon while doing EK combined with cataract surgery. The hyperopic shift is hypothesized to be due to the lenticular creating a negative power at the posterior corneal surface36.

Visual outcome: The average visual acuity after DSAEK is about 20/40 as described in various studies37,38,39. In a large series of 5160 patients of FECD, Shah et al39 found a mean visual acuity of 20/31. Similar results were given by others40,41 with a reported mean visual acuity of 20/38 and 20/35, respectively. As the surgical techniques and visual outcomes are improving, so are the expectations of the patients. Even though visual results are great post-DSAEK, some patients are not happy which could be because of the interface irregularities42,43. There are reports in which well-functioning EK grafts have been replaced because of poor visual quality44. This has been corroborated by confocal microscopy42 of donor-recipient interface and wavefront aberrometry43,45 which also prove the recipient stroma to be the cause for visual quality degradation.

Complications of Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty

Graft failure: The incidence of primary graft failure has been well-documented post-PKP and has been reported to be approximately 10 per cent46, but there are very few studies for DSAEK to document the rate of primary graft failure and loss of endothelial cell count per year. While a decrease of 15 per cent in endothelial cell density (ECD) is seen post-PKP47,48, a decrease of 36 per cent in ECD post-DSAEK has been documented by Terry et al49. Price and Price50 found similar results and a drop of 34 per cent in their report on 263 post-DSAEK eyes. Terry et al51 evaluated the effect of donor, recipient and operative factors on graft success in the Cornea Preservation Time Study and found that graft success was more in cases of FECD, cases without any intra-operative complications and if the donor did not have diabetes.

Graft dislocation: The most common complication encountered post-DSAEK is dislocation of the graft, which requires rebubbling in the immediate to early post-operative period. The rate of dislocation has been reported to be 1-82 per cent52. Price and Price50 included FECD patients and found a low rate (6.5%) of dislocations. However, other authors41,53 have reported a dislocation rate of 26 and 23 per cent, respectively.

Graft rejection: As lesser amount of corneal tissue is transplanted in DSAEK as compared to PKP, we expect a lower rejection rate in DSAEK. It has also been seen that DSAEK patients present with very subtle rejection signs. The rejection episodes are usually asymptomatic and detected incidentally on routine examination. Various authors have reported similar graft rejection rates. Jordan et al54 did a study on 598 patients and found a rejection rate of 9 per cent. Allan et al55 reported a rejection rate of 7.5 per cent in DLEK cases and a similar rate of 7.5 per cent was reported by Terry et al56,57 in their study on 80 eyes.

Other complications: Pupillary block glaucoma is very commonly seen after DSAEK surgery in immediate post-operative period because of the residual air bubble. It can be avoided by doing an intra-operative inferior peripheral iridectomy. Graft infection, infiltrates in the interface, endophthalmitis can also be seen after DSAEK. In the late post-operative period, epithelial ingrowth in the interface might occur. The incidence of pupillary block glaucoma has been reported to be between 0.149 and 9.5 per cent58. Besides peripheral iridectomy, another way to avoid pupillary block is to leave a freely mobile air bubble after surgery. Terry et al49 followed this method and found only one case of a pupillary block in about 850 cases of DSAEK, i.e. a rate of 0.1 per cent.

The epithelial ingrowth in the interface is thought to occur because of epithelium gaining access into the interface through the full-thickness venting incisions that were used to release the interface fluid59,60. Epithelial ingrowth has also been seen in the anterior chamber and over the donor if there are vitreous attachments to the wound61. Graft infection or interface infection is usually difficult to manage and may require therapeutic PKP ultimately62. Another vision-threatening complication that can be seen post-DSAEK or PKP is endophthalmitis. It is even worse if caused due to fungal organisms.

Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK)

Visual outcomes: Noble et al63 found best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/6 in 24.7 per cent cases while 84.9 per cent had visual acuity better than 6/12. Amayem and Anwar64 in a study on keratoconus patients found a visual acuity better than 6/9 in 95.8 per cent cases at one year post-operative follow up. Anwar and Teichmann65 reported a BCVA better than 6/9 in 27 per cent cases and Coombes et al66 found it to be 64 per cent at one year follow up. Watson et al67 reported BCVA of 6/6 or better in 64 per cent patients of PKP and 32 per cent of DALK patients. Funnell et al68 corroborated the above results in their cohort study with 70 per cent of PKP patients achieving BCVA of 6/6 or better as compared to 22 per cent patients of DALK achieving a similar visual outcome. However, there are some studies, which do not follow the above pattern. Trimarchi et al69 found the mean visual acuity to be higher in patients undergoing DALK as compared to PKP.

Complications of DALK

Descemet membrane (DM) perforation: Noble et al63 noted an incidence of 13.8 per cent DM perforation in their study. Various authors reported a variable percentage of DM perforation. While Watson et al67 corroborated the results of the above study with a 15 per cent rate of DM perforation, other authors reported rates as low as four per cent69 and as high as 39.2 per cent70.

DM perforation is most likely to occur over the apex of the cone, which is the thinnest point and can be avoided by practicing caution while dissecting over thin cornea as well manipulating the spatula in a way that it remains superficial over the thin areas of the cornea. It can also occur while removing the peripheral ledge from host cornea and even during passing sutures. Sugita and Kondo70 reported this complication in 39.2 per cent of their cases, but none required conversion to PKP.

Graft rejection: DALK is rarely seen to be associated with graft rejection with reported rates to be as low as 5-8 per cent67. Graft rejection post-DALK was first reported in 197371. It could be sight-threatening just like graft rejection seen in PKP and is avoidable by intensive steroid therapy72. There are various advantages of DALK over PKP as DALK is a closed globe surgery and thus intraocular complications such as suprachoroidal haemorrhage, retinal detachment are reduced. Further, steroids are needed for a short period as well as in a lower dose because of the low risk of graft rejection.

Penetrating keratoplasty (PKP)

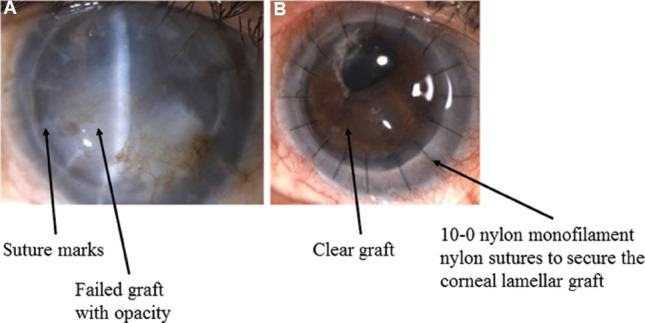

There have been various studies to evaluate the visual outcomes and complications post-PKP. It is done for full thickness opacities such as healed keratitis, post-traumatic scars, corneal dystrophies with endothelial involvement as well as corneal decompensation with anterior stromal scarring (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Clinical photographs (A) showing operated penetrating keratoplasty with failed graft; (B) post-operative day one picture with clear graft and well-apposed graft-host junction.

Visual outcome: Brahma et al73 did a study on 18 patients with keratoconus to evaluate the visual outcome after PKP. They found an improvement in visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and glare acuity post-PKP. Their results were corroborated by an improvement in Visual Function-14 scores. Rahman et al74 reported a BCVA of more than 6/12 in 48 per cent patients at five years of follow up. Similarly, Beckingsale et al75 found that about 50 per cent of patients achieved visual acuity better than 6/18.

Complications

Graft rejection: Rahman et al74 reported an incidence of 21 per cent of graft rejection episodes, of which 7.4 per cent eventually went into graft failure. Pramanik et al76 reported a graft failure rate of 6.3 per cent at 20 years, and a similar failure rate of seven per cent has been reported in a study with 326 eyes77. Pramanik et al76 found early graft failure to be rare, Olson et al78 did not report a single case of early graft failure within 24 months while Paglen et al77 reported five cases, i.e. 1.5 per cent of early graft failure.

Other complications: PK, being an open globe procedure, is associated with catastrophic complications such as expulsive choroidal haemorrhage. The introduction of LK significantly reduces the incidence of this grave complication. PKP is associated with suture-related problems such as loose sutures, suture infiltrates as well as suture-associated astigmatism. Post-PKP astigmatism is one of the common causes of low-vision post-keratoplasty clear graft. There are various methods of reducing suture-related astigmatism. Topography assisted suture rotation, selective suture removal/replacement, placement of compression sutures can help reduce astigmatism in early post-operative period79. In late post-operative period, ablative procedures or arcuate keratotomies can be used. Another important cause of loss of vision post-PKP is post-PKP glaucoma. The various parameters which can contribute to an increase in the incidence of glaucoma are the presence of pre-existing glaucoma, increased intra-operative manipulation, severe inflammation in the post-operative period.

Eye banking in the modern era

Organ donation is a complicated process as it involves many social, ethical and legal issues. As the number and techniques of corneal transplantations are increasing, so is the need for donor corneas contributing to a demand-supply shortage, especially in developing countries. To keep up with the growing demand of donor corneas, the first eye bank was started in New York by Paton in 194480. To further promote eye banking and establish uniform standards and rules, ten such eye banks in America joined hands to form the Eye Bank Association of America (EBAA)80. They were able to transplant 41,300 corneas during 1994 and the major source of their tissues were hospitals81. Another achievement that helped in the progress of eye banking was the development of corneal storage media.

The revolution reached India in 1945 when the first eye bank was developed in Madras (now Chennai)81. In 1993, as reported by the various eye banks of India, approximately, 6413 corneal grafts were done and it has come a long way since then81. Legislation to control eye banking and eye donation was first passed in India in 195781.

Legal issues in eye banking

The Transplantation of Human Organs Act was passed in 199481. It was mainly to control the illegal trafficking and sale of kidneys, but it mentioned: ‘eyes and ears can be harvested anywhere by a registered medical practitioner'. There were still some legal hurdles like the need for a registered medical practitioner and the need for blood bank and intensive care unit. The Act was amended in 201181 after feedback from experts from National Eye Bank (NEB) and Eye Bank Association of India (EBAI). It was published in the National Gazette as Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Rules 201482. As per this Act, cornea was considered as tissue and not an organ, the consent for the donation was extended from legal next of kin to other relatives such as grandchildren and henceforth, trained technicians were allowed to retrieve corneas.

Another provision that has greatly increased eye retrieval is the introduction of Hospital Cornea Retrieval Programme (HCRP)83. A study84 was done to evaluate the factors affecting eye donation in post-mortem cases. It was done with the help of trained counsellors using a set format of questions. It was found that only 55.4 per cent people were aware of eye donation, of whom only 44.3 per cent volunteered to donate. This acknowledged the importance of active counselling by trained counsellors in hospital mortuaries and wards and the Delhi centralized Hospital Cornea Retrieval Programme (HCRP) was initialized in association with SightLife85. It can work effectively if there is good coordination between the medical officers, nurse, health personnel, technicians, forensic experts, and the legal system.

Role of eye bank

Eye bank plays a great role in cornea harvesting, processing, and record keeping. It takes care of the various steps during harvesting, first of all, defining the optimum time between death and recovery. It is preferably taken as less than 12 h as there are fewer chances of infection as well a better quality of tissue81. The eye bank keeps a vigil on controlling quality during harvesting, transportation, processing and storage until it reaches the surgeon. It is important to ensure complete asepsis during retrieval of the cornea as any source of infection can lead to vision-threatening complications such as graft infection and endophthalmitis. Multiple cases of post-keratoplasty graft infection have been reported because of the organisms present in the storage media86. The donor scleral rim should always be sent for microbiological evaluation, and the patient should initially be kept on early follow up to pick up signs of graft infection and early intervention.

Recent advancements

Various advancements in techniques have evolved which help to improve the outcomes of keratoplasty, of which intra-operative optical coherence tomography (iOCT) and femtosecond laser are most important.

Intra-operative optical coherence tomography (iOCT)

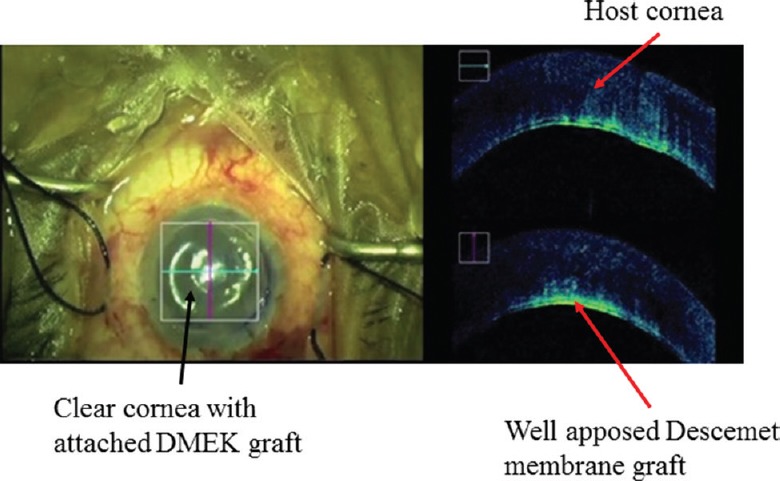

The iOCT provides continuous feedback of intra-operative surgical manoeuvres. It is very useful in LK such as SALK, ALTK, DALK, DSEK and DMEK. The iOCT helps in the measurement of central corneal thickness (CCT) of the donor as well as host cornea both of which are important parameters for deciding the blade size to be used in microkeratome for dissection. Furthermore, in cases of manual preparation of donor tissue, it acts as an intra-operative guiding tool to minimize complications. In cases of SALK, ALTK, proper apposition can be done with the help of iOCT. In DALK procedure, the iOCT guides every step of the surgery starting from depth of trephination to graft-host apposition87. During big bubble DALK, the air needle can be passed under iOCT guidance to know the adequate depth for achieving big bubble, thereby decreasing chances of intra-operative perforation. In manual DALK, it helps in identifying a thinner location so that extra precaution can be taken while manoeuvring in and around the same area. Any small perforation in DALK can be identified easily and further steps may be taken to avoid the case getting converted to full thickness PKP. In cases of DSAEK88, it helps in identifying the right orientation of graft and also ensures adequate apposition of host and donor cornea at the end of surgery. Small peripheral detachments, fluid pockets, reverse orientation of graft, interface debris can be picked up easily on iOCT, which would otherwise be very difficult to pick in hazy oedematous corneas under microscopic view89. Juthani et al89 have concluded the presence of transient interface fluid seen on iOCT to be associated with the textural interface opacity in the long-term follow up. Again, in DMEK89, right orientation of scroll can be identified by its configuration under iOCT. There are three different orientations, which have been described in iOCT of which DMEK scroll with upside rolling is considered as right orientation (Figs 13 & 14).

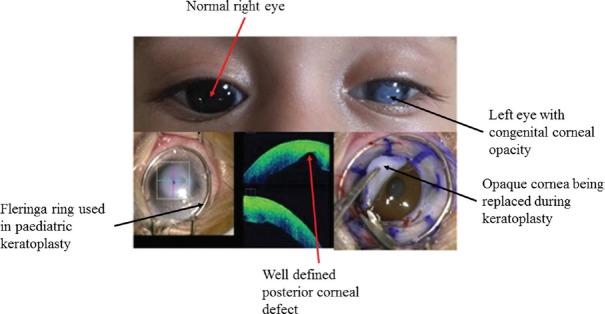

Fig. 13.

Clinical photograph of a child with left eye congenital corneal opacity along with an intra-operative photograph showing a very well-defined posterior corneal defect confirming the diagnosis of Peter's anomaly.

Fig. 14.

Intra-operative photograph showing the well-apposed Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) lenticule on intra-operative optical coherence tomography.

Femtosecond laser-assisted lamellar keratoplasty (FALK)

FALK has many advantages over manual keratoplasty. Lamellar, as well as full-thickness PKP, can be performed using femtosecond laser90. The sharp and accurate cut of different shapes in recipient and donor cornea results in perfect alignment of tissues reducing post-operative problems such as epithelial healing and astigmatism. It leads to better incision geometry, accurate graft-host apposition, and better wound healing. If the host and donor cuts are in perfect alignment, there is less postoperative astigmatism91. It avoids a mismatch between host and donor as can be seen sometimes in manual keratoplasty with the trephination being eccentric. FALK increases graft-host interface surface area and thereby increasing the strength of graft-host junction and thus, decreasing risk for graft dehiscence92. It is associated with less endothelial cell loss at the margin of a graft. During LK, it helps in smooth dissection. While microkeratome-assisted lamellar keratoplasty helps in dissecting a pre-decided depth of tissue, FALK, when combined with intra-operative OCT, helps in a more accurate analysis of the depth of opacity and preparation of customized grafts93.

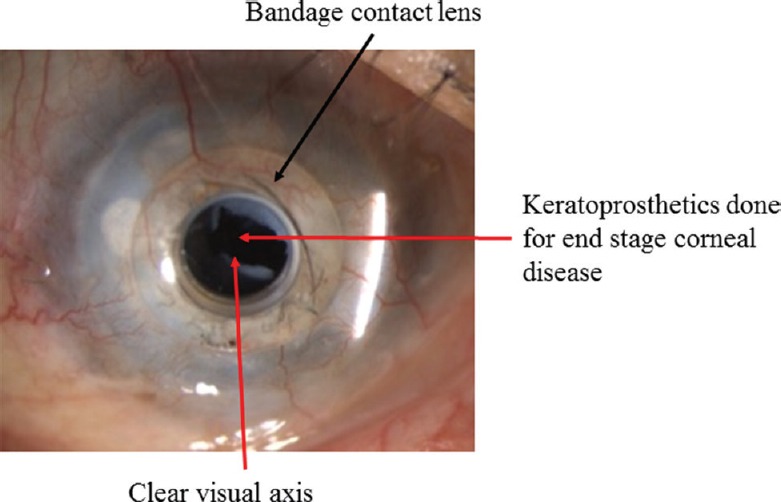

Bioengineered cornea

Several methods have been developed to manage the gap between donor availability and its requirement for visual rehabilitation. One of the methods is the development of bioengineered corneas. These are designed to replace the full thickness of the diseased cornea or a part of the diseased cornea. These range from keratoprosthesis (Fig. 15), which replaces the function of the cornea to the recent development of tissue-engineered hydrogels that help in the regeneration of host tissues94. Furthermore, there are bioengineered lenticules that can be used to correct the refractive errors by implantation into the cornea. There have been important developments in this area in the last few years with clinical trials being conducted for the artificial cornea, development of natural corneal replacements and biosynthetic matrices for host tissue regeneration95. Buznyk et al96 conducted a study to assess the safety and efficacy of bioengineered corneas grafted as an alternative to human donor corneas in high-risk patients. They reported that bioengineered RHCIII-MPC (recombinant human collagen type III and 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) implants could be better alternatives to donor tissues in repairing corneas with severe pathologies but a large sample study size along with a longer follow up is needed to confirm the efficacy of such bioengineered implants.

Fig. 15.

Clinical picture showing operated keratoprosthesis (K-pro) with operated membranectomy for retroprosthetic membrane.

Conclusion

Over a century has passed since the first corneal transplantation surgery was performed in Europe in 1905, and since then, there has been no looking back. Customized component corneal replacement strategies to replace diseased layers and conserve healthy components and ever improving instrumentation and engineering marvels have helped reach greater heights of sight restoration with faster recovery, better quality of vision, more reliable sight restoration, minimization of complications and greater longevity and success rates. Pari passu improvements in eye banking techniques have greatly helped the surgical results. The future holds promise with further optimization of results and pushing of boundaries of care, widening the scope of services to reach remote areas and underserved populations with the help of ever expanding horizons of medical science and engineering to approach new pinnacles.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Zirm EK. Eine erfolgreiche totale Keratoplastik (A successful total keratoplasty).1906. Refract Corneal Surg. 1989;5:258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, et al. Global survey of corneal transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:167–73. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhanda RP, Kalevar V. Historical review. International ophthalmic clinics. Boston, MA: Little Brown Co; 1972. Corneal surgery; pp. 7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Hippel A. Eine neue methode der hornhauttransplantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1888;34:108–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trevor Roper PD. The history of corneal grafting. In: Casey TA, editor. Corneal grafting. London: Butterwork; 1972. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rycroft BW, Romanes GJ. Lamellar corneal grafts clinical report on 62 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1952;36:337–51. doi: 10.1136/bjo.36.7.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moffatt SL, Cartwright VA, Stumpf TH. Centennial review of corneal transplantation. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33:642–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paufique L, Sourdille GP, Offret G. Les Greffes de la corne´e. Paris: Masson; 1948. p. 159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barraquer JI. Queratomileusispara la correccion de la myopia. Arch Soc Am Oftalmol Optom. 1964;5:27–48. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barraquer JI. Lamellar keratoplasty. (Special techniques) Ann Ophthalmol. 1972;4:437–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman HE. The correction of aphakia. XXXVI Edward Jackson memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman HE, Insler MS, Ibrahim-Elzembely HA, Kaufman SC. Human fibrin tissue adhesive for sutureless lamellar keratoplasty and scleral patch adhesion: A pilot study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2168–72. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archila EA. Deep lamellar keratoplasty dissection of host tissue with intrastromal air injection. Cornea. 1984;3:217–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vajpayee RB, Vasudendra N, Titiyal JS, Tandon R, Sharma N, Sinha R, et al. Automated lamellar therapeutic keratoplasty (ALTK) in the treatment of anterior to mid-stromal corneal pathologies. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:771–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melles GR, Rietveld FJ, Beekhuis WH, Binder PS. A technique to visualize corneal incision and lamellar dissection depth during surgery. Cornea. 1999;18:80–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anwar M, Teichmann KD. Big-bubble technique to bare Descemet's membrane in anterior lamellar keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:398–403. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)01181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tillett CW. Posterior lamellar keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;41:530–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(56)91269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barraquer J. Special methods in corneal surgery. In: King JH, McTigue JW, editors. The comea world congress. Washington, DC: Rutterworths; 1965. pp. 586–604. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko WW, Freuh B, Shields C, Costello ML, Feldman ST. Experimental posterior lamellar transplantation of the rabbit cornea (ARVO abstract) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:1102. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melles GR, Eggink FA, Lander F, Pels E, Rietveld FJ, Beekhuis WH, et al. A surgical technique for posterior lamellar keratoplasty. Cornea. 1998;17:618–26. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melles GR, Lander F, Nieuwendaal C. Sutureless, posterior lamellar keratoplasty: A case report of a modified technique. Cornea. 2002;21:325–7. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200204000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty in the first United States patients: Early clinical results. Cornea. 2001;20:239–43. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melles GR, Wijdh RH, Nieuwendaal CP. A technique to excise the descemet membrane from a recipient cornea (descemetorhexis) Cornea. 2004;23:286–8. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorovoy MS. Descemet-stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2006;25:886–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214224.90743.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melles GR, Ong TS, Ververs B, van der Wees J. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) Cornea. 2006;25:987–90. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000248385.16896.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price MO, Giebel AW, Fairchild KM, Price FW., Jr Descemet's membrane endothelial keratoplasty: Prospective multicenter study of visual and refractive outcomes and endothelial survival. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darlington JK, Adrean SD, Schwab IR. Trends of penetrating keratoplasty in the United States from 1980 to 2004. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Röck T, Landenberger J, Bramkamp M, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Röck D. The evolution of corneal transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2017;22:749–54. doi: 10.12659/AOT.905498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang AQ, Rubenstein D, Price AJ, Côté E, Levitt M, Sharpen L, et al. Evolving surgical techniques of and indications for corneal transplantation in Ontario: 2000-2012. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le R, Yucel N, Khattak S, Yucel YH, Prud'homme GJ, Gupta N, et al. Current indications and surgical approaches to corneal transplants at the University of Toronto: A clinical-pathological study. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52:74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zare M, Javadi MA, Einollahi B, Karimian F, Rafie AR, Feizi S, et al. Changing indications and surgical techniques for corneal transplantation between 2004 and 2009 at a tertiary referral center. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:323–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.97941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park CY, Lee JK, Gore PK, Lim CY, Chuck RS. Keratoplasty in the United States: A 10-year review from 2005 through 2014. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2432–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta N, Vashist P, Tandon R, Gupta SK, Dwivedi S, Mani K, et al. Prevalence of corneal diseases in the rural Indian population: The corneal opacity rural epidemiological (CORE) study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:147–52. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogla R, Padmanabhan P. Initial results of small incision deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupps WJ, Jr, Qian Y, Meisler DM. Multivariate model of refractive shift in Descemet-stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:578–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jun B, Kuo AN, Afshari NA, Carlson AN, Kim T. Refractive change after Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty surgery and its correlation with graft thickness and diameter. Cornea. 2009;28:19–23. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318182a4c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macsai MS, Kara-Jose AC. Suture technique for Descemet stripping and endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2007;26:1123–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318124a443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price MO, Price FW., Jr Descemet's stripping with endothelial keratoplasty: Comparative outcomes with microkeratome-dissected and manually dissected donor tissue. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1936–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah AK, Terry MA, Shamie N, Chen ES, Phillips PM, Hoar KL, et al. Complications and clinical outcomes of Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty with intraocular lens exchange. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:390–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price MO, Baig KM, Brubaker JW, Price FW., Jr Randomized, prospective comparison of precut vs.surgeon-dissected grafts for Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Brien PD, Lake DB, Saw VP, Rostron CK, Dart JK, Allan BD, et al. Endothelial keratoplasty: Case selection in the learning curve. Cornea. 2008;27:1114–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318180e58b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi A, Mawatari Y, Yokogawa H, Sugiyama K. In vivo laser confocal microscopy after Descemet stripping with automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel SV, Baratz KH, Hodge DO, Maguire LJ, McLaren JW. The effect of corneal light scatter on vision after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:153–60. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen ES, Shamie N, Terry MA, Hoar KL. Endothelial keratoplasty: Improvement of vision after healthy donor tissue exchange. Cornea. 2008;27:279–82. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815be9e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hindman HB, McCally RL, Myrowitz E, Terry MA, Stark WJ, Weinberg RS, et al. Evaluation of deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty surgery using scatterometry and wavefront analyses. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson RW, Jr, Price MO, Bowers PJ, Price FW., Jr Long-term graft survival after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1396–402. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oster SF, Ebrahimi KB, Eberhart CG, Schein OD, Stark WJ, Jun AS, et al. A clinicopathologic series of primary graft failure after Descemet's stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:609–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel SV. Graft survival and endothelial outcomes in the new era of endothelial keratoplasty. Exp Eye Res. 2012;95:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terry MA, Shamie N, Chen ES, Hoar KL, Phillips PM, Friend DJ, et al. Endothelial keratoplasty: The influence of preoperative donor endothelial cell densities on dislocation, primary graft failure, and 1-year cell counts. Cornea. 2008;27:1131–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181814cbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Price MO, Price FW., Jr Endothelial cell loss after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty influencing factors and 2-year trend. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:857–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terry MA, Aldave AJ, Szczotka-Flynn LB, Liang W, Ayala AR, Maguire MG, et al. Donor, recipient, and operative factors associated with graft success in the Cornea Preservation Time Study. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:1700–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arenas E, Esquenazi S, Anwar M, Terry M. Lamellar corneal transplantation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:510–29. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soong HK, Fitzgerald J, Boruchoff SA, Sugar A, Meyer RF, Gabel MG, et al. Corneal hydrops in Terrien's marginal degeneration. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:340–3. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33737-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jordan CS, Price MO, Trespalacios R, Price FW., Jr Graft rejection episodes after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty: Part one: Clinical signs and symptoms. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:387–90. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allan BD, Terry MA, Price FW, Jr, Price MO, Griffin NB, Claesson M, et al. Corneal transplant rejection rate and severity after endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2007;26:1039–42. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812f66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terry MA. Endothelial keratoplasty: Clinical outcomes in the two years following deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (an American Ophthalmological Society Thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:530–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty visual acuity, astigmatism, and endothelial survival in a large prospective series. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1541–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bessant DA, Dart JK. Lamellar keratoplasty in the management of inflammatory corneal ulceration and perforation. Eye (Lond) 1994;8(Pt 1):22–8. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saelens IE, Bartels MC, Van Rij G, Dinjens WN, Mooy CM. Introduction of epithelial cells in the flap-graft interface during Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:936–7. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bansal R, Ramasubramanian A, Das P, Sukhija J, Jain AK. Intracorneal epithelial ingrowth after Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty and stromal puncture. Cornea. 2009;28:334–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181907c00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phillips PM, Terry MA, Kaufman SC, Chen ES. Epithelial downgrowth after Descemet's stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:193–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koenig SB, Wirostko WJ, Fish RI, Covert DJ. Candida keratitis after Descemet stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2009;28:471–3. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818ad9bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noble BA, Agrawal A, Collins C, Saldana M, Brogden PR, Zuberbuhler B. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) Cornea. 2007;26:59–64. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000240080.99832.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amayem AF, Anwar M. Fluid lamellar keratoplasty in keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:76–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anwar M, Teichmann KD. Deep lamellar keratoplasty: Surgical techniques for anterior lamellar keratoplasty with and without baring of Descemet's membrane. Cornea. 2002;21:374–83. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200205000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coombes AGA, Kirwan JF, Rostron CK. Deep lamellar keratoplasty with lympholised tissue in the management of keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:778–91. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watson SL, Ramsay A, Dart JK, Bunce C, Craig E. Comparison of deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty in patients with keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Funnell CL, Ball J, Noble BA. Comparative cohort study of the outcomes of deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:527–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trimarchi F, Poppi E, Klersy C, Piacentini C. Deep lamellar keratoplasty. Ophthalmologica. 2001;215:389–93. doi: 10.1159/000050894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sugita J, Kondo J. Deep lamellar keratoplasty with complete removal of pathological stroma for vision improvement. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:184–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maumenee AE. Clinical patterns of corneal graft failure. Ciba Found Symp. 1973;15:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al-Torbak A, Malak M, Teichmann KD, Wagoner MD. Presumed stromal graft rejection after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty. Cornea. 2005;24:241–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000141230.95601.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brahma A, Ennis F, Harper R, Ridgway A, Tullo A. Visual function after penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: A prospective longitudinal evaluation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:60–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rahman I, Carley F, Hillarby C, Brahma A, Tullo AB. Penetrating keratoplasty: Indications, outcomes, and complications. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1288–94. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beckingsale P, Mavrikakis I, Al-Yousuf N, Mavrikakis E, Daya SM. Penetrating keratoplasty: Outcomes from a corneal unit compared to national data. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:728–31. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.086272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DC, Sutphin JE, Farjo AA. Extended long-term outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1633–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paglen PG, Fine M, Abbott RL, Webster RG., Jr The prognosis for keratoplasty in keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:651–4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Olson RJ, Pingree M, Ridges R, Lundergan ML, Alldredge C, Jr, Clinch TE, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: A long-term review of results and complications. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:987–91. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ho Wang Yin G, Hoffart L. Post-keratoplasty astigmatism management by relaxing incisions: a systematic review. Eye Vis (Lond) 2017;4:29. doi: 10.1186/s40662-017-0093-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brightbill FC, editor. Corneal surgery: Theory, technique and tissue. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saini JS, Reddy MK, Jain A K, Ravindra M S, Jhaveria S, Raghuram L. Perspectives in eye banking. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1996;44:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.The Gazette of India. Transplantation of Human Organs Acts and Rules. [accessed on October 20, 2018]. pp. 1–72. Available from: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/THOA-Rules-2014%20%281%29.pdf .

- 83.Tandon R, Singh A, Gupta N, Vanathi M, Gupta V. Upgradation and modernization of eye banking services: Integrating tradition with innovative policies and current best practices. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:109–15. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_862_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tandon R, Verma K, Vanathi M, Pandey RM, Vajpayee RB. Factors affecting eye donation from postmortem cases in a tertiary care hospital. Cornea. 2004;23:597–601. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000121706.58571.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Impact of eye donation counselors and trained nurses in hospital cornea retrieval program. [accessed on October 20, 2018]. Available form: http://restoresight.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/0935-Tandon-Impact-of-Eye-Donation-Counselors-and-Trained-Nurses_Sapna.pdf .

- 86.Panda A, Satpathy G, Sethi HS. Survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in M-K preserved corneas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:679–83. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.050674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steven P, Le Blanc C, Lankenau E, Krug M, Oelckers S, Heindl LM, et al. Optimising deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) using intraoperative online optical coherence tomography (iOCT) Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:900–4. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pasricha ND, Shieh C, Carrasco-Zevallos OM, Keller B, Izatt JA, Toth CA, et al. Real-time microscope-integrated OCT to improve visualization in DSAEK for advanced bullous keratopathy. Cornea. 2015;34:1606–10. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Juthani VV, Goshe JM, Srivastava SK, Ehlers JP. Association between transient interface fluid on intraoperative OCT and textural interface opacity after DSAEK surgery in the PIONEER study. Cornea. 2014;33:887–92. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Farid M, Steinert RF. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty performed with the femtosecond laser zigzag incision for the treatment of stromal corneal pathology and ectatic disease. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:809–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shousha MA, Yoo SH, Kymionis GD, Ide T, Feuer W, Karp CL, et al. Long-term results of femtosecond laser-assisted sutureless anterior lamellar keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:315–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoo SH, Kymionis GD, Koreishi A, Ide T, Goldman D, Karp CL, et al. Femtosecond laser–assisted sutureless anterior lamellar keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1303–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wirbelauer C, Winkler J, Bastian GO, Häberle H, Pham DT. Histopathological correlation of corneal diseases with optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:727–34. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Griffith M, Jackson WB, Lagali N, Merrett K, Li F, Fagerholm P, et al. Artificial corneas: A regenerative medicine approach. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1985–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carlsson DJ, Li F, Shimmura S, Griffith M. Bioengineered corneas: How close are we? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14:192–7. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Buznyk O, Pasyechnikova N, Islam MM, Iakymenko S, Fagerholm P, Griffith M, et al. Bioengineered corneas grafted as alternatives to human donor corneas in three high-risk patients. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8:558–62. doi: 10.1111/cts.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]