Abstract

Background

In underserved areas, it is crucial to investigate ways of increasing access to hearing health care. The community health worker (CHW) is a model that has been applied to increase access in various health arenas. This article proposes further investigation into the application of this model to audiology.

Purpose

To assess the feasibility of training CHWs about hearing loss as a possible approach to increase accessibility of hearing health support services in an underserved area.

Research Design

A specialized three-phase training process for CHWs was developed, implemented, and evaluated by audiologists and public health researchers. The training process included (1) focus groups with CHWs and residents from the community to raise awareness of hearing loss among CHWs and the community; (2) a 3-hr workshop training to introduce basic topics to prepare CHWs to identify signs of hearing loss among community members and use effective communication strategies; and (3) a 24-hr multisession, interactive training >6 weeks for CHWs who would become facilitators of educational and peer-support groups for individuals with hearing loss and family members.

Study Sample

Twelve Spanish-speaking local CHWs employed by a federally qualified health center participated in a focus group, twelve received the general training, and four individuals with prior experience as health educators received further in-person training as facilitators of peer-education groups on hearing loss and communication.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data was collected from each step of the three-phase training process. Thematic analysis was completed for the focus group data. Pre- and posttraining assessments and case study discussions were used to analyze results for the general workshop and the in-depth training sessions.

Results

CHWs increased their knowledge base and confidence in effective communication strategies and developed skills in facilitating hearing education and peer-support groups. Through case study practice, CHWs demonstrated competencies and applied their learning to specific situations related to effective communication with hearing loss, family support, availability of assistive technology, use of hearing protection, and making referrals for hearing health care. Needs were identified for ongoing training in the area of use of assistive technology and addressing situations of more severe hearing loss and its effects.

Conclusions

Initial results suggest it is feasible to train CHWs to engage community members regarding hearing loss and facilitate culturally relevant peer-health education and peer-support groups for individuals with hearing loss and their family members. In efforts to increase access to audiological services in rural or underserved communities, application of the CHW model with a partnership of audiologists deserves further consideration as a viable approach.

Keywords: access, aural rehabilitation groups, community health workers, disparities, hearing loss, Spanish

Introduction

Across the United States, many people who live with hearing loss have not accessed audiological services. About 30 million adults have hearing loss in both ears (Lin et al, 2011); however, <20% access hearing aids (Chien and Lin, 2012; Nash et al, 2013). Among Mexican Americans, the proportion of affected individuals who access treatment is even lower, at an estimated 4–10% (Lee et al, 1991; Nieman et al, 2016). This number is concerning, given that nearly one in seven Hispanic/Latino adults in the United States has hearing loss (Cruickshanks et al, 2015). The US–Mexico border region, which has a large Hispanic/Latino population, has been characterized by physician shortages, high levels of poverty, unemployment, and disease (Collins-Dogrul, 2006; United States-México Border Health Commission, 2010a,b; Border Research Partnership, 2013).

To address the health disparities facing US–Mexico border communities, as well as other underserved populations, members of these same communities can be trained to promote health and provide disease prevention and basic intervention services in a culturally relevant manner (Hunter et al, 2004; O'Brien et al, 2009; Swider et al, 2010; Ingram et al, 2012). These individuals, known as “community health workers (CHWs)” or “promotoras (de salud)” in Spanish, serve as intermediaries between health professionals and patients, not only connecting people to services but also advocating for their individual health needs as frontline workers (Nemcek and Sabatier, 2003). Though the CHW model has been used to address health disparities related to a myriad of health issues (Norris et al, 2006; Ingram et al, 2007; Cornejo et al, 2011; Philis-Tsimikas et al, 2011; Ingram et al, 2012; Koniak-Griffin et al, 2015), we found no evidence that it has yet been applied to the issue of outreach among adults with hearing loss in the United States. In the global hearing health context, there have been examples of CHW roles in hearing screening and community-based rehabilitation (World Health Organization, 2006; 2012; Araújo et al, 2013). Other examples of CHW roles related to hearing loss have involved increasing access to primary health care for persons with hearing loss who are deaf or deaf-blind (Jones et al, 2005).

Management of hearing loss through aural rehabilitation includes the following four primary overlapping approaches: sensory management through provision of hearing assistive devices (hearing aids, cochlear implants, etc.), instruction, perceptual and communication training, and psychosocial counseling targeting issues of participation and quality of life (Boothroyd, 2007). One way to implement the counseling and education component is by creating a supportive group environment. Audiological rehabilitation groups have been shown to benefit individuals with hearing loss by providing a venue for self-expression, improving their communication through the use of strategies, reducing social and emotional withdrawal, and increasing self-awareness of hearing aids and other assistive technology (Chisolm et al, 2004; Hawkins, 2005; Hickson et al, 2007). These groups have contributed to an increase in the quality of life for family members and friends of those who have hearing loss by providing them with tools to improve communication, increasing realistic expectations, and attaining a better understanding of their partners' hearing loss (Preminger, 2003).

The use of aural rehabilitation groups as a means to provide education, counseling, and peer support for individuals with hearing loss presents an opportunity to extend application of the CHW model to address disparities in hearing health care to underserved communities in culturally relevant ways. The current study is part of ongoing National Institutes of Health–funded research to develop and test the effectiveness of a CHW model to reduce disparities in access to hearing health care among rural, Hispanic/Latino older adults in the United States. The study is based on an academic–community partnership among audiology, public health, translation studies, and CHWs of a federally qualified health center (FQHC) in an Arizona community. In the current article, we illustrate how the CHWs identified a lack of hearing loss education as a disparity in their community and expressed a desire for further instruction on this topic. This resulted in the training of CHWs in audiology and hearing loss topics by the academic partners composed of audiology clinicians, researchers, and bilingual audiology graduate students. The three-phased training process included (a) focus groups with community members to identify unmet needs related to hearing health care; (b) a workshop to prepare CHWs to identify signs of hearing loss among community members and use effective communication strategies; and (c) additional training for CHWs who would become facilitators of a hearing health outreach program culturally and linguistically tailored to the primarily Spanish-speaking, rural Mexican American community. Preliminary process and outcomes evaluation of the CHW trainings suggest that the application of the CHW model, in conjunction with the expertise of audiology researchers and clinicians, deserves further exploration.

Methods

Training and Learning Framework

The goal of the training was for the CHWs to become prepared to recognize the effects of hearing loss on individuals and their families and to respond with appropriate referrals and communication strategies, and for experienced health educators to become facilitators of peer-support groups for hearing loss and to teach self-management techniques and effective communication strategies for this chronic health condition. The Freire Empowerment Educational Model (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1988) was the basis of the training and learning framework. Table 1 outlines the training phases and critical learning activities for the CHWs within the framework of Freire's model. In the Freire Empowerment Model, learning is supported through reflection and action, and equal emphasis is placed on the knowledge of the student and the teacher. The CHWs' knowledge and connection to their community was recognized as an integral component of the training process. Use of this framework focused the training process on empowering CHWs to recognize problems and potential solutions regarding hearing loss in their community.

Table 1. Training Phases and Corresponding Critical Learning Activities for CHWs.

| Training Phase | Critical Learning Activities | Bloom's Taxonomy of Critical Learning | Step within Freire Empowerment Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Focus groups of CHWs (n = 12); interviews and focus groups with Nogales residents | Remember/experiential learning | Listening |

| 2 | General workshop (12 CHWs) | Understand | Pose problems |

| 3 | In-depth training (3 CHWs, 1 project manager) | Evaluate analyze apply | Act-reflect-act |

| Ongoing support and supervision | Pilot hearing health education and support groups | Create | Act-reflect-act |

Note: Table data is from the Framework of the Freire Empowerment Model (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1988) and Learning Objectives Classified along the Cognitive Process Dimension of the Revised Bloom's Taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2010).

The three steps in the Freire Empowerment Educational Model are listening, pose problems, and act-reflect-act. Listening requires engaging community members as colearners in identifying their own needs. This was accomplished through a series of focus groups completed with CHWs and community members of the area. The second step, pose problems, requires a discussion and critical thinking about solutions for complex problems. This step was accomplished during meetings between the academic partners and the CHWs to discuss the issues raised in the focus groups and general workshop. The third step, act-reflect-act, requires individuals to take action within the community and apply their learning. This critical step involved the academic partners training the CHWs on a set of hearing-related topics that included both knowledge and skill competencies so that the staff could take action to support individuals with hearing loss in their community.

Setting

Nogales, AZ, is a US–Mexico border city with a population of 20,948 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Approximately 13.8% of the population is >65 yr of age. The FQHC is the major primary health care provider for Santa Cruz County, AZ. Despite having several programs for the aging population, the FQHC had not systematically or pro-grammatically addressed hearing loss among their clients.

Participants

Participants were female CHWs employed by the FQHC in the Platicamos Salud program, now Community Health Services. The main requirement for a CHW is to be a member of the community they serve and to exhibit leadership characteristics within the context of the community. CHWs then receive on-the-job training, both in the core competencies of CHWs (Rosenthal et al, 2011) and on specific health conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer (see Table 2 for further information about CHWs). CHWs' responsibilities for this health center include offering outreach, advocacy and education, practical instruction, personal assistance (e.g., social support, transportation), and referral services for community members in a language- and culture-appropriate manner. Their health promotion activities also include participation in health fairs and campaigns and follow-up for programs and interventions through home visits. At this health center, the workforce is supported by a professional public health team.

Table 2. Further Information Regarding CHWs.

| CHWs | |

|---|---|

| Definition | “A community health worker is a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables the worker to serve as a liaison/ link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery.” (www.apha.org/) |

| Characteristics | Nonjudgmental, altruistic, trustworthy, creativity to adapt interventions, follow healthy lifestyle habits, effective communication skills, ability to work with others. (Cornejo et al, 2011; Steps Forward, National Institutes of Health) |

| Rationale | “The community health worker model is predicated on … social networks, social support, participatory education, and community empowerment. The community health worker model involves systematic training and support of trusted and respected community members who engage in community outreach, participatory health education, and provision of social support to others within their personal and community social networks. The theoretical rationale is that community health workers contribute to community empowerment and social change as they engage community members in participatory education processes of consciousness raising, dialogue, and reflection (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1988). In turn, the increased individual and community-level capacity building and empowerment contribute to improved access and utilization of health knowledge, resources, and services and to decreased health disparities.” (Koskan et al, 2013; p. 391) |

Because cross-training is a strong component of the CHW model, all the CHWs of the FQHC were invited to attend a focus group (training phase 1, n = 12) and a general 3-hr workshop (training phase 2, n = 12). Four individuals continued with the in-depth training after the general workshop (three CHWs and their health promotion manager). The CHWs involved in the third phase of the training were selected on the basis of their extensive work experience and specific skills as assessed by their manager, including interest in hearing loss, willingness to learn, compassion and empathy, and leadership and advocacy.

The CHWs who participated in the third phase of training were full-time CHWs, each with >15 yr of experience and ages ranging from 58 to 73 yr. They were native Spanish speakers, all of whom were born in Mexico and later immigrated to the United States. These CHWs were employed by the FQHC, with salary support through the health programs and grant-funded projects they take part in. They typically work on three to four programs/projects in the community at a time. The types of projects these CHWs have been involved in include facilitating cancer support groups, offering women's health and fitness programs, conducting oral health screening for children, evaluating the exercise environments of southern Arizona for childhood obesity prevention, and leading diabetes educational groups.

Training Procedures

CHW Focus Groups

As part of the “listening” step in the Freire Empowerment Educational model, the academic partners facilitated a focus group with 12 CHWs from the FQHC. This was done to assess CHW awareness of issues related to hearing loss among their clients, identify CHW training needs, and clarify aspects of the CHW model that would integrate well with an aural rehabilitation approach for an outreach program addressing access to care and the quality-of-life effects of hearing loss. Four additional focus groups were facilitated by the CHWs with individuals that the CHWs recruited from the community who self-identified as having hearing loss, or family members of those with hearing loss. The CHWs were trained on how to lead focus groups for people with hearing loss. All five of the focus groups lasted ∼2 hr, were conducted in Spanish; digitally audio recorded; and then transcribed, coded, and analyzed for thematic content by the academic partners. (Detailed results of these community focus groups will be presented elsewhere.)

Meetings with Academic Partners

As part of the “pose problems” step in the Freire Empowerment Educational model, the CHWs met with the academic partners to discuss the topics that arose in the focus groups. The CHWs identified a need to offer hearing loss education in their community and specifically expressed the desire for further specific training that would enable them to facilitate hearing loss education and support groups to empower community members and increase access to care.

General 3-hr Workshop

As part of the “act-reflect-act” step in the Freire Empowerment Educational model, a general 3-hr workshop was held for all the CHWs at the FQHC. The format was an interactive discussion-based training that used PowerPoint as a presentation tool for didactic class materials and discussion prompts, as well as a number of interactive activities, including a hearing loss simulation and video otoscopy. The workshop included information about the anatomy and physiology of the auditory system; various lifestyle, communication, and emotional effects that may be caused by hearing loss; and a general introduction to communication strategies and assistive devices. Throughout the workshop, an emphasis was placed on the importance of making appropriate referrals for clients to audiology, otolaryngology, and speech-language pathology when there are hearing, ear, or speech-language concerns.

Community Hearing Screenings

The CHWs who participated in the general workshop subsequently collaborated with the academic partners to hold two community hearing screening events. Over 90 adult community members attended for hearing screenings provided in-kind by audiologists and supervised audiology graduate students from the research team. The CHWs recruited people to attend the screenings based on their knowledge and awareness gained from the general training by discussing hearing with participants of their other ongoing health and wellness programs and word-of-mouth interactions within the community. The success of this community-engaged process also helped to confirm the community's perceived need to address hearing health in Santa Cruz County.

In-Depth CHW Training

As part of the act-reflect-act step in the Freire Empowerment Educational model, three experienced CHWs and the health promotion manager participated in 24 additional hours of audiological training that included eight sessions >6 weeks. The sessions were led in Spanish by two bilingual, bicultural audiology graduate students (DS and AS) and supervised by audiology faculty (SA, FPH, and NM). An outline of the training curriculum is provided in Appendix 1. The topics were selected based on a review of the literature and best-practice guidelines, the focus group data that revealed the community's hearing loss educational needs, the open-ended responses from the general workshop evaluations indicating training needs, and the expertise of the academic partners. Existing curricula for audiology assistants and audiology technicians were also reviewed; however, the research team found that these materials were focused on roles supporting the work of clinic-based audiologists and not specific to the promotoras' unique role as nonclinical, community liaisons. Consideration was made to include topics related to the effects of hearing loss not only at the individual level, but also the family and community levels in response to the needs expressed during the focus group process. The information regarding appropriate referrals to health professionals was again reinforced.

Evaluation Measures

Focus Groups

The research team used N-Vivo software (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia) (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006) to conduct thematic content analysis of the focus group data. Several themes emerged from these analyses that explored the perspective of CHWs concerning (a) their awareness of hearing loss as a health issue, (b) their experiences in dealing with hearing loss and its effects on clients, (c) the potential for CHWs to address hearing loss.

General 3-hr Workshop

A case study discussion and posttraining measures were used to evaluate the general 3-hr workshop. At the end of the general 3-hr workshop, the CHWs were presented with a case study example of an adult client with hearing loss facing isolation issues due to his hearing loss and communication difficulties with family members speaking to him from different rooms. This served to form a group discussion and provided the CHWs the opportunity to recall and apply the information on communication strategies and audiology referrals they had learned during the workshop. The academic partners assessed the validity and accuracy of the CHWs' responses. The CHWs were also asked to complete a 3-mo postmeasure in which they rated the usefulness of the information on topics, such as hearing loss, audiometry, and communication strategies, and the ease or clarity of the information. The 3-mo postmeasure also asked the CHWs to describe in what ways they were more aware of hearing loss following the workshop, the most interesting or new information they learned in the workshop, and how the workshop impacted them or their work.

In-Depth Training

Various case study discussions and pre- and post-training measures were used. Before the beginning of each training session, the CHWs completed one premeasure containing five to seven open-ended questions assessing levels of knowledge on aspects of the audiology training that were to be presented that session. An example for the “How We Hear” session included “What are three causes of hearing loss?” One question in each premeasure was dedicated to asking the CHWs “What is the most important thing that you would like to know about this topic?” to make the subsequent training as relevant and specific as possible to their interests and their community's educational needs. Additionally, multiple case study examples were used throughout the training sessions to assess the CHWs' competency in recommending audiology or medical referrals for hearing-related concerns, and suggesting effective communication strategies to clients.

The posttraining assessment included seven comprehensive knowledge-based questions that allowed the academic partners to assess the CHWs' competency in hearing loss–related concepts. The questions asked the CHWs to list common causes of hearing loss, describe basic factors that affect the outcomes of hearing aid use, name communication strategies that improve communication, describe basic information that can be understood from an audiogram, and list examples of hearing assistive technology systems. The posttest was administered to ensure that the CHWs' knowledge of basic concepts was deemed accurate by the academic partners. The posttraining assessment also included six questions that assessed their skills, knowledge, and confidence (before and after the training sessions) in facilitating a hearing education and support group for individuals with hearing loss. The CHWs were asked to rate their level of confidence in facilitating a group for adults and families living with hearing loss and in helping individuals to protect their hearing, improve their use of hearing aids, improve their communication, understand their hearing test results, and use hearing assistive devices. Examples of the post-training questions are listed in Appendix 2.

Results

Training Phase 1: CHW Focus Group

The analysis of the CHW focus group data revealed that while some CHWs reported concerns about hearing loss among their own family members, many of the CHWs had not thought about hearing loss among other members of the community or its impact on health before the focus group. They also reported that they had never received information or training on the topic. Of note is the fact that hearing loss had not been emphasized to them as a health issue “We all know about diabetes and how to manage it, but hearing … we don't know much. We just aren't that conscious of it here in Nogales.” Upon reflection, however, the CHWs gave/several examples of hearing loss impeding their interactions with clients. The predominant example was their awareness that clients with hearing loss were not benefitting as much as would be expected from other group health education classes.

There are those individuals who cannot hear and pretend like they understand the topic but once you ask them more about it you realize they are completely wrong.

In our diabetes class, there is a man who comes with a family member and has a hearing aid. During the class, he seems lost. I can tell he is trying to pay attention but he cannot follow … so he always seems quiet and uninterested and doesn't interact much.

The focus group results also indicated that because of the lack of resources in their rural community, the CHWs felt that there was little they could offer their clients beyond making suggestions that they have more patience with individuals who have hearing loss. Additionally, the CHWs were determined in their requests for education on hearing loss; the effects of hearing loss on communication, health, and family life; effective communication strategies; available hearing assistive technology; and community resources for clinical care and self-management.

Training Phase 2: Evaluation of General 3-hr Workshop

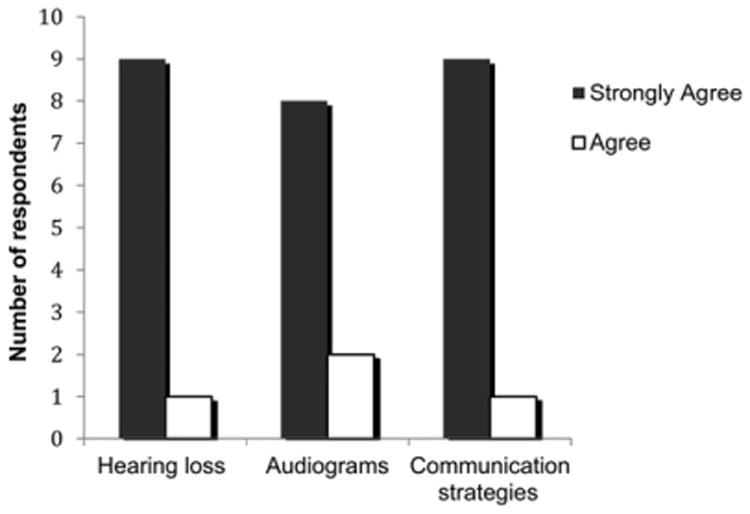

Through the case study discussion, the academic partners determined that the CHWs were competent in introductory information regarding recommending referrals to audiology and the use of communication strategies for individuals with hearing loss. Ten of 12 (83%) CHWs who attended the general 3-hr workshop returned a 3-mo posttraining evaluation. The posttraining evaluation contained eight questions, of which three were self-rating content questions, three were open-ended perception questions, and two directly related to the format of the training. Of the posttraining evaluations that were received, 100% of the CHWs gave a rating of “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” with the following statement, “The information about ______ (hearing loss, audiograms, communication strategies) helped me to understand my/my partner's/my clients' hearing loss better.” Figure 1 depicts these results.

Figure 1.

Ratings of agreement with statements about the benefit of training content by CHWs (n = 12) using a response scale of Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree.

Lastly, on the 3-mo posttraining evaluation, the CHWs responded to a question on their perceptions of training needs for hearing-related topics and a desire to help community members with hearing loss. For example,

“I would like more classes and to learn more so that I can help my community. It's a topic that is not discussed, at least for promotoras.”

“The information was great… hopefully we can share this information with our community.”

Responses to the three open-ended questions on the 3-mo posttraining evaluation further described the issues and challenges facing the community from the CHW's perspective. Some of the issues described included the limited resources in their community and the lack of importance attributed to hearing loss by society. In addition, from the case study discussion held at the end of the 3-hr workshop, the CHWs expressed that the information about hearing loss was new, relevant, and applicable to their community (Table 3).

Table 3. Responses of CHWs from the Evaluation of the 3-hr Workshop on Hearing Loss and Effective Communication Strategies.

| Question | Example Responses |

|---|---|

| What was the most surprising/interesting thing that you learned? | “That we must be patient with people who don't understand us because sometimes it's because they can't hear us.” “It (hearing loss) is a common problem and we don't give it any importance. We need to educate ourselves about it, and educate our community.” “How hearing loss can affect the entire family.” |

| After the presentation, have you noticed that you are more aware of hearing loss? | “Of course, now I'll be more cautious of my surroundings because I know how sensitive it (the ear) is to damage.” “Yes, especially (more aware) with the elderly and young children.” |

| How has the information impacted you? | “Learning more about all of the effects it (hearing loss) has.” “Many times we think that people don't want to respond or they selectively listen, but now I can recommend family members, friends and patients to get their hearing tested.” “It impacted me learning how many people have hearing loss, and how few resources exist.” |

Training Phase 3: Evaluation of In-Depth Training Sessions

The in-depth training was effective in increasing the CHWs' knowledge of hearing loss and audiology-related concepts, and increasing the CHWs' confidence to lead a support group for hearing loss. All the CHWs were able to correctly answer all the knowledge-based questions with 100% accuracy. Group mean scores revealed that the CHWs increased their confidence in facilitating a health education group for adults with hearing loss and their families in all the categories (Table 4).

Table 4. CHW Self-Efficacy Confidence Ratings for Applying Learning to Implement a Hearing Wellness Program in Their Community.

| Question | Pretraining Average (SD) | Posttraining Average (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| How confident are you that you can help people with hearing loss to protect their hearing? | 1.75 (0.94) | 4.5 (0.57) |

| How confident are you in your ability to advise participants on how to improve the use of hearing aids? | 1.25 (0.5) | 4 (0) |

| How confident are you that you can help people with hearing loss and their family members to communicate? | 1.5 (0.57) | 4.5 (0.57) |

| How confident are you in your ability to explain to a client what their audiogram means (overall)? | 1.25 (0.5) | 4 (0.81) |

| How confident are you in your ability to use hearing devices (not hearing aids) to help people with hearing loss? | 1 (0) | 3.75 (0.44) |

| How confident are you in your ability to facilitate a group program for people with hearing loss? | 1.75 (0.95) | 4.5 (0.57) |

Notes: n = 4. SD = standard deviation. Rating: 1 = not at all confident and 5 = very confident.

Through the case study discussions, the academic partners determined that the CHWs were competent in recommending referrals and applying their learning of hearing loss topics. For example, when asked “What are three factors that improve the success of hearing aid users?” responses included “motivation to use the devices, realistic expectations, the right hearing aid for the particular person (molded to ear, programmed correctly), family support, getting used to their hearing aids.”

Discussion

These preliminary results suggest that training CHWs about hearing loss, and thereby applying the CHW model, is a new approach that has potential to increase access to hearing health care in rural or un-derserved areas. Further research in this area is critical due to the disparity in accessing hearing health care services in underserved areas. As future facilitators of hearing health education and support outreach programs, it is vital the CHWs be taught factual and valid information through a systematic approach. The expertise provided by the academic partners from audiology guided the development of the training and ensured the information presented to the CHWs was accurate and valid. This partnership then allows accurate information to be disseminated by the CHWs in culturally relevant ways. Through the case studies and postoutcome assessments, the CHWs' knowledge regarding basic information on hearing loss was verified.

As revealed by the CHW focus group, hearing health may be unrecognized or devalued as a health priority in communities facing major health disparities for several reasons. First, hearing loss is not life-threatening, and second, there is a general view that little can be done to improve quality of life beyond the prohibitive cost of hearing aids. Thus, a community–academic partnership such as the one presented here can assist health agencies in assessing the need for intervention services and providing a cost-effective and accessible hearing health intervention that can be beneficial to clients with or without assistive devices. Further, the use of the CHW model provides a means to access a difficult-to-reach population and connect those in the community needing audiological and other clinical referrals with the hearing health care system.

The ability for CHWs to effectively communicate without language barriers and on a personal level with community members, as well as the already established role of the CHWs at the FQHC site, places them in a unique role as hearing health education and support group facilitators in efforts to expand access to audiological services. The community–academic partnership used in this study facilitated colearning and shared development of learning objectives that would allow the CHWs to begin to address hearing loss in their communities and facilitate access to hearing health care. The foundation of the CHW model is that as members and leaders of their communities, CHWs are the experts in identifying and responding to health issues facing community members in culturally appropriate ways (HSRA, 2007). The CHWs' expertise as leaders in their own community made them exemplary individuals to inform the academic partners and provide feedback and suggestions about the adaptation of the hearing health education program discussed in this article. Through the trainings provided and guided by the academic partners, our pilot results suggest that the CHWs are prepared to deliver information on hearing loss in culturally relevant ways to their community members. We also found that experienced CHWs are able to gain sufficient familiarity with audiology-related concepts at a layperson's level, such as explaining the basic results of a hearing screening to a community member, helping individuals to protect their hearing by applying knowledge of various forms of hearing protection, and understanding basic information on the time-intensity trade-off related to noise exposure. This study established the need for new knowledge related to hearing loss among CHWs in a rural, US–Mexico border community.

Further development of the training curriculum to evaluate and test its applicability in other communities, as well as defining the level of ongoing supervision and support needed to sustain a hearing loss outreach program, is in progress. Only a small number of CHWs went on to participate in the initial offering of the in-depth training due to the scope of the project. As such, we recommend additional investigation of this training with a larger and more diverse group of CHWs, and with a control group to compare pre- and posttraining outcomes. Without having a control group to compare with the training results, it is difficult to identify other variables (biases, sample size) that could have contributed to the CHWs' increase in knowledge and confidence. Additionally, the academic partners were not aware of any existing standardized outcome measures available for assessing CHWs in hearing loss topics. Consequently, the measures used in this study were basic by design and did not use technical language, as the CHWs are laypersons rather than clinicians. This highlights a further research need to create standardized outcome measures for training purposes.

The training program on hearing loss for CHWs developed here was implemented within a single FQHC. This health center is located in a border community with a primarily Spanish-speaking patient population. Therefore, some needs of this health center and CHW staff may be specific to this community setting, while others may be present within other health centers or for CHWs serving other minority or underserved populations. We recommend additional training and further objective evaluation measures at timed intervals to assess the CHW's long-term retention of hearing loss–related knowledge and communication skills. In-depth statistical analysis of the CHWs' pre- and postoutcomes and long-term retention are the objectives for future projects. Additionally, we recommend evaluating the individuals who will participate in the hearing outreach programs facilitated by the CHWs.

Applications of this project in other underserved areas must take several factors into account. These include the CHWs' work experience, specifically experience in facilitating group discussions; any linguistic and cultural differences in the local area; the interpretation or translation of the information; and the aims of the project. The CHWs who were trained and participated in this project had extensive experience facilitating support groups, and advocating for patients through medical and home visits. If this project is implemented in other areas with CHWs who have less experience facilitating support groups, then it is imperative to provide further training on how to foster group discussions and ways to ensure that the participants share personal accounts during the group sessions. Additionally, the language and dialects spoken in a specific community should be factored into the application of a similar project. The translation of the information on hearing loss must consider the purpose that the materials are expected to accomplish, including audience characteristics such as their linguistic and socioeconomic traits, and health literacy. Throughout the trainings, the CHWs provided feedback on the Spanish word choices used when materials were translated or created directly in Spanish. They edited the word choices that they deemed confusing or unclear for the Spanish spoken in Nogales, AZ. Further information about the language mediation and translation process our research team undertook can be found in Colina et al (2016).

If a similar project is implemented in other areas, the aim of the project must be carefully considered when training the CHWs. If a goal is to train the CHWs in competency-based tasks, such as obtaining case history information or performing hearing screenings, the training program would need to be appropriately designed, documented, and implemented following best-practice guidelines. In this project, the training did not include technical activities such as administering hearing screenings because the aim was focused on the CHWs' roles as recruitment and health education facilitators due to their unique connection to the community members. After awareness was raised around hearing health, the CHWs trained for this project were able to successfully find and recruit individuals with suspected hearing loss. The academic–community partnership in this project allowed the audiology partners to provide all of the hearing screening resources to identify and counsel community members regarding hearing health care.

In conclusion, the preliminary results presented in this article suggest that integrating the CHWs expertise in culturally competent health education with the audiologist's clinical expertise has potential as an approach to reduce disparities in accessing hearing health care in disadvantaged areas. We propose further research on this topic, given the high level of disparity in accessing hearing health care across underserved populations. As members of their own communities who share similar life experiences and culture, CHWs play a vital role through social support and community trust. Because of this, they have a unique skill set in culturally relevant communication, problem-solving, and support of behavior change that some clinicians may not possess to reach individuals in disadvantaged areas. The CHWs who participated in this training curriculum are currently facilitating hearing health education and support groups for individuals with hearing loss and their families. The training curriculum for CHWs is currently being revised for future dissemination. Future projects include formalizing this training for others, analyzing the cost-effectiveness of such a training program, and potential application in other rural health areas or in other underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the promotoras for their commitment to this shared project, inspiring dedication to their communities, and enthusiasm to help families affected by hearing loss.

Research reported in this publication was supported by The University of Arizona Foundation, the James S. and Dyan Pignatelli/Unisource Clinical Chair in Audiologic Rehabilitation for Adults at The University of Arizona, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21/R33 DC013681.

Abbreviation

- CHW

community health worker

- FQHC

federally qualified health center

Appendix 1

Outline of Topics for Each 3-hr Interactive Session, the Material Covered, and the Pre/Post Evaluation Measures for CHW Facilitator Training Sessions.

| Training Session | Topics | Pre/Post Knowledge Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | How we hear | |

| What is sound (simple and complex acoustic signals) Basic anatomy of the outer/middle/inner ear, auditory brainstem, and cortical pathways, binaural hearing, localization Introduction to hearing loss types (categories of severity, progressive vs. sudden vs. temporary threshold shifts) |

Common causes of and risk factors for hearing loss likely to be encountered in the community The role of acoustics and anatomy in the basic understanding of hearing loss |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Videos depicting various frequencies, decibels, examples of acoustic reverberation, absorption, and decreasing sound level with distance. Videos depicting basic auditory physiology including sound passing through the outer ear through the auditory cortex. | ||

| 2 | Hearing loss | |

| Hearing loss epidemiology Auditory disorders (presbycusis, otitis media, ototoxicity, Meniere's, tinnitus) Discussion of cultural practices and home remedies for hearing- and ear-related concerns, as these arose during the focus groups |

Knowledge of the scale of the impact of hearing loss in the United States Recognize common causes of hearing loss and auditory disorders Debunking common myths that do not improve someone's hearing or ear concerns Case studies |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Videos and images depicting various hearing loss types and degrees of severity. Case study examples depicting individuals facing various auditory disorders and their symptoms. Group discussion concerning home remedies common to their community. | ||

| 3 | Hearing aids | |

| Hearing aid functions Types/styles Cost Process of obtaining hearing aids |

Basic hearing aid function Various hearing aid styles for various lifestyle and patient needs Introductory information about obtaining hearing aids Case studies |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| CHWs were fit with low-gain open-fit hearing aids during this session. Group discussion about their experience “hearing” with a hearing aid. Video depicting hearing aid technology changes over time. Video depicting a cochlear implant simulation. | ||

| 4 | Hearing aids | |

| Cleaning and maintenance Factors that affect successful use Realistic expectations |

Factors that contribute to the success of hearing aid use Realistic expectations for individuals who have hearing loss and want to purchase hearing aids Case studies |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Demonstration of several hearing aid types. Discussion of hearing aid trial periods, warranties, and contracts. | ||

| 5 | Communication, strategies, and emotions | |

| Communication Factors that impede successful communication for individuals with hearing loss and their communication partners (family members, friends) The negative emotions that may arise due to hearing loss The differences in the emotions of the person with hearing loss and the communication partner Strategies that may improve communication for those with hearing loss and their communication partners |

Building blocks of communication Deterrents to successful communication for individuals with hearing loss The negative effects on the communication partner Use of communication strategies for individuals with hearing loss and their communication partner Case studies |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Discussion regarding factors that impede successful communication. Hearing loss simulation activity. Role-play of communication breakdowns and group discussion of communication strategies. Speech-reading activity to demonstrate the importance of contextual information when communicating. | ||

| 6 | Hearing tests and the health care team | |

| Air- and bone-conduction audiometric testing Interpreting the audiogram, other audiologic tests (otoacoustic emissions, tympanometry, auditory brainstem response) Differences in test procedures for adults vs. pediatric patients Information about the existing hearing health care resources in their community |

Basic understanding of an audiogram Testing differences for adults and children Knowledge of community resources Case studies |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Group discussion about case study examples depicting individuals with hearing loss concerns, and introductory hearing aid questions. CHWs underwent hearing screenings and tympanometry testing. | ||

| 7 | Hearing conservation, hearing assistive technology systems, and advocacy | |

| Noise exposure The time-intensity trade-off Types of hearing protection Hearing assistive technology (demonstrations of TV EARS and looped systems) Advocacy information for individuals with hearing loss, with emphasis on the Americans with Disabilities Act |

How to protect one's hearing Hearing assistive technology systems that may be beneficial for individuals with hearing loss Advocacy rights and hearing loss accommodations Case studies |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Videos depicting the intensities of various environmental sounds and videos depicting corresponding hair cell damage. Demonstration of proper ear plug placement. Demonstrations with assistive technology including infrared, hard-wired, FM, induction loops, captioned telephones, and alerting systems such as vibrotactile alarms. Video depicting how induction loops work. | ||

| 8 | Techniques for facilitating a group program for persons with hearing loss | |

| How to arrange the physical environment for communication access How to structure the group and communication ground rules How to elicit discussion among group members related to communication and coping How to manage communication breakdowns and interactions between members of the group |

Group examples Practical skills in using microphones, sound field amplification system, and group FM system |

|

| Interactive component | ||

| Role-play and simulated group discussions. Hands-on practice setting up the assistive technology systems. | ||

Appendix 2

Examples of the pretest questions that were repeated in the posttraining assessment:

What are two causes of hearing loss?

Name two risk factors for developing hearing loss.

What are two realistic expectations for hearing aids?

Name two strategies that improve communication.

Name two assistive listening devices (other than hearing aids).

What would you like to learn about hearing aids?

Examples of the posttraining assessment questions:

What are two things you must take into account when leading a group for people with hearing loss?

How confident are you that you can help people with hearing loss protect their hearing?

How confident are you that you can improve an individual's use of hearing aids?

Footnotes

Preliminary data were presented at the meeting of the American Auditory Society, March 6, 2015, Scottsdale, AZ.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Araújo ES, de Freitas Alvarenga K, Urnau D, Pagnossin DF, Wen CL. Community health worker training for infant hearing health: effectiveness of distance learning. Int J Audiol. 2013;52(9):636–641. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.791029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd A. Adult aural rehabilitation: what is it and does it work? Trends Amplif. 2007;11(2):63–71. doi: 10.1177/1084713807301073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Border Research Partnership. Quality of Life. In: Lee E, Wilson C, editors. The State of the Border Report: a Comprehensive Analysis of the U S-Mexico Border. Washington, DC: Mexico Institute, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chien W, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):292–293. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisolm TH, Abrams HB, McArdle R. Short- and long-term outcomes of adult audiological rehabilitation. Ear Hear. 2004;25(5):464–477. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000145114.24651.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colina S, Marrone N, Ingram M, Sánchez D. Translation quality assessment in health research: a functionalist alternative to back translation. Eval Health Prof. 2016:1–27. doi: 10.1177/0163278716648191. Epub ahead of print May 19, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Dogrul J. Managing US-Mexico “border health”: an organizational field approach. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3199–3211. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo E, Denman CA, Sabo S, De Zapién J, Rosales C. Scoping Review of Community Health Worker/Promotora-Based Chronic Disease Primary Prevention Programs on the U S-Mexico Border. Avance de Investigación, El Colegio de Sonora; Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshanks KJ, Dhar S, Dinces E, Fifer RC, Gonzalez F, 2nd, Heiss G, Hoffman HJ, Lee DJ, Newhoff M, Tocci L, Torre P, 3rd, Tweed TS. Hearing impairment prevalence and associated risk factors in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(7):641–648. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DB. Effectiveness of counseling-based adult group aural rehabilitation programs: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Acad Audiol. 2005;16(7):485–493. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16.7.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson L, Worrall L, Scarinci N. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the active communication education program for older people with hearing impairment. Ear Hear. 2007;28(2):212–230. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JB, de Zapien JG, Papenfuss M, Fernandez ML, Meister J, Giuliano AR. The impact of a promotora on increasing routine chronic disease prevention among women aged 40 and older at the U.S.-Mexico border. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(4, Suppl):18S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram M, Piper R, Kunz S, Navarro C, Sander A, Gastelum S. Salud Sí: a case study for the use of participatory evaluation in creating effective and sustainable community-based health promotion. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(2):130–138. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31824650ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram M, Reinschmidt KM, Schachter KA, Davidson CL, Sabo SJ, De Zapien JG, Carvajal SC. Establishing a professional profile of community health workers: results from a national study of roles, activities and training. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9475-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram M, Torres E, Redondo F, Bradford G, Wang C, O'Toole ML. The impact of promotoras on social support and glycemic control among members of a farmworker community on the US-Mexico border. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(6, Suppl):172S–178S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Renger R, Firestone R. Deaf community analysis for health education priorities. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22(1):27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.22105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniak-Griffin D, Brecht ML, Takayanagi S, Villegas J, Melendrez M, Balcázar H. A community health worker-led lifestyle behavior intervention for Latina (Hispanic) women: feasibility and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskan AM, Friedman DB, Brandt HM, Walsemann KM, Messias DK. Preparing promotoras to deliver health programs for Hispanic communities: training processes and curricula. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(3):390–399. doi: 10.1177/1524839912457176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krathwohl DR. A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Pract. 2010;41(4):212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Carlson DL, Lee HM, Ray LA, Markides KS. Hearing loss and hearing aid use in Hispanic adults: results from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(11):1471–1474. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FR, Niparko JK, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1851–1852. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash SD, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang GH, Klein BE, Klein R, Nieto FJ, Tweed TS. Unmet hearing health care needs: the Beaver Dam offspring study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):1134–1139. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemcek MA, Sabatier R. State of evaluation: community health workers. Public Health Nurs. 2003;20(4):260–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman CL, Marrone N, Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Lin FR. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in hearing health care among older Americans. J Aging Health. 2016;28(1):68–94. doi: 10.1177/0898264315585505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, Horsley T, Brownstein JN, Zhang X, Jack L, Jr, Satterfield DW. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):544–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, Larson SC. Role development of community health workers: an examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6, Suppl 1):S262–S269. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philis-Tsimikas A, Fortmann A, Lleva-Ocana L, Walker C, Gallo LC. Peer-led diabetes education programs in high-risk Mexican Americans improve glycemic control compared with standard approaches: a Project Dulce promotora randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1926–1931. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preminger JE. Should significant others be encouraged to join adult group audiologic rehabilitation classes? J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14(10):545–555. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.14.10.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: An overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(3):247–259. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RE. Steps Forward Manual. National Institutes of Health, The University of Arizona, and Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swider SM, Martin M, Lynas C, Rothschild S. Project MATCH: training for a promotora intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(1):98–108. doi: 10.1177/0145721709352381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Welcome to QuickFacts Nogales City, Arizona. U.S. Department of Commerce; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions (HSRA) Community Health Worker National Workforce Study: An Annotated Bibliography. 2007 http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/chwstudy2007.pdf.

- United States-México Border Health Commission. Border Lives: Health Status in the United States-México Border Region. Comisión de Salud Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos; 2010a. pp. 1–362. [Google Scholar]

- United States-México Border Health Commission. Health Disparities and the U S -México Border: Challenges and Opportunities: A White Paper. Comisión de Salud Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos; 2010b. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Primary Ear and Hearing Care Training Resource. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Community-Based Rehabilitation: Promoting Ear and Hearing Care through CBR. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]