Abstract

Recent interest in exposures to ultrafine particles (less than 100 nm) in both environmental and occupational settings led us to question whether the protocols used to certify respirator filters provide adequate attention to ultrafine aerosols. We reviewed the particle size distribution of challenge aerosols and evaluated the aerosol measurement method currently employed in NIOSH particulate respirator certification protocol for its ability to measure the contribution of ultrafine particles to filter penetration. We also considered the differences between mechanical and electrically charged (electret) filters in light of the most penetrating particle size. We found that the NaCl and DOP aerosols currently used in respirator certification tests contain a significant fraction of particles in the ultrafine region. However, the photometric method deployed in the certification test is not capable of adequately measuring light scatter of particles below approximately 100 nm in diameter. Specifically, 68% (by count) and 8% (by mass) of the challenge NaCl aerosol particles and 10% (by count) and 0.3% (by mass) of the DOP particles below 100 nm do not significantly contribute to the filter penetration measurement. Additionally, the most penetrating particle size for electret filters likely occurs at 100 nm or less under test conditions similar to those used in filter certification. We conclude, therefore, that the existing NIOSH certification protocol may not represent a “worst-case” assessment for electret filters because it has limited ability to determine the contribution of ultrafine aerosols, which include the most penetrating particle size for electret filters. Possible strategies to assess ultrafine particle penetration in the certification protocol are discussed.

Keywords: respirator, certification, filtration, ultrafine, particle

INTRODUCTION

Particulate-filtering respirators marketed in the United States are subjected to performance certification prior to becoming commercially available. Certification ensures that respirators meet prescribed performance criteria intended to ensure a minimum level of user protection. Certification also results in an explicit stratification of respirator types and classes that aid the health and safety professional in selecting a level of protection appropriate for a specific hazard.

U.S. Government approval of respirators began in 1919 when the Bureau of Mines promulgated Approval Schedule 13 for self-contained breathing apparatuses [1]. Approval requirements for other respirator types followed and certification requirements for particulate-filtering respirators were promulgated in 1934. With several modifications, the Bureau of Mines requirements eventually became the core respirator certification tests adopted by the newly-formed National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in 1972 [2].

Currently, NIOSH certifies respirators in accordance with Title 42 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, section 84 (42 CFR 84) [3]. The regulations—adopted in current form in 1995—prescribe minimum performance requirements for respirator components and systems. Filtration efficiency of air-purifying particulate filters, the focus of this paper, is certified under 42 CFR 84.181, Non-powered air-purifying particulate filter efficiency level determination. Respirators are certified in one of nine classes based upon three levels of filtration efficiency and three levels of resistance to filter degradation (see Table I).

TABLE I.

Non-Powered Particulate Air-Purifying Respirator Classification (summary)

| Respirator | Minimum Filtration Efficiency % | Challenge Aerosol | Max Filter Loading | Usage Limitation | Certification PreconditioningC | Certification Flowrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N95 | 95 | NaCl | 200 mg | Non-oil aerosols only | Y | 85 lpm |

| R95 | 95 | DOP | 200 mg | 8-hrs/one workshiftA | N | |

| P95 | 95 | DOP | Lowest efficiency | Per user instructionsB | N | |

| N99 | 99 | NaCl | 200 mg | Non-oil aerosols only | Y | |

| R99 | 99 | DOP | 200 mg | 8-hrs/one workshiftA | N | |

| P99 | 99 | DOP | Lowest efficiency | Per user instructionsB | N | |

| N100 | 99.97 | NaCl | 200 mg | Non-oil aerosols only | Y | |

| R100 | 99.97 | DOP | 200 mg | 8-hrs/one workshiffA | N | |

| P100 | 99.97 | DOP | Lowest efficiency | Per user instructionsB | N |

In oil aerosol environment.

P-series respirator filter service life recommendations are manufacturer specific.

N-series filters require preconditioning at 85% relative humidity and 38°C for 25 hours.

Respirator filtration efficiency is tested and certified for 95%, 99%, or 99.97% removal of challenge aerosol particles. These respirators are respectively labeled as “95”, “99”, or “100” class efficiency. Filter series is categorized as “N”, “R”, or “P”, based upon the type of aerosol used for testing. N-type filters are intended to protect workers from solid particulates and are tested against a mildly degrading sodium chloride (NaCl) aerosol; R-type filters demonstrate resistance to liquid particulates and are tested against a more highly degrading dioctylphthalate (DOP) oil aerosol; and P-type filters are highly resistant to degradation and are tested against DOP until filter efficiency is at its lowest level [3].

Since respirator users encounter a wide variety of aerosols under varying conditions, respirator testing is a combination of “worst case” and “very severe” conditions [3]. Research has shown mild filtration degradation when N-type filters are stored in high relative humidity conditions [4]. Consequently, filters undergo preconditioning at 85% relative humidity and 38°C for 25 hours prior to testing [3, 4]. The generated challenge aerosols are “charge-neutralized,” which increases filter penetration when compared to charged aerosol particles [3, 5]. The test aerosols are intended to be at (or near) the assumed most penetrating particle size of 0.3 μm in aerodynamic diameter [3, 6, 7]. Since the respirator wearer’s breathing minute ventilation can alter filter efficiency an airflow of 85 lpm (or 42.5 lpm for dual filter respirators) is used to represent a worker’s inhalation at a high work rate [3, 7].

Respirator certification is intended to be a conservative test in order to assure a minimum level of filtration in a wide variety of workplaces, with differing aerosol characteristics, environmental conditions, and workloads [3]. The current certification protocol, however, may not address the filter efficiency against ultrafine particles (with a diameter less than 0.1 micrometers = 100 nm), although this fraction is of special interest in environmental and occupational hygiene for several reasons [8]. Due to high surface area per unit mass, ultrafine particles often have significantly different biological activity compared to larger airborne particles of the same composition [9]. Patterns of respiratory deposition of ultrafine particles are not well-characterized and there are no accepted particle-size selective criteria for their monitoring [8, 10, 11]. Occupational sources of ultrafine particles are numerous. Some common sources involve combustion, such as diesel or aircraft exhaust, or welding fume generation [8]. Additionally, concern over appropriate protection against bioaerosols has increased in recent years. Microbial fragments have been observed in the ultrafine size range and it is hypothesized that viruses can be aerosolized in the ultrafine size range as droplet nuclei or single virions [12, 13]. Lastly, recent developments in nanotechnology have resulted in a considerable interest in the health and safety aspects of engineered nanoparticles. These materials, used in a wide variety of commercial applications and products, include particulate materials < 100 nm in size which are engineered and manufactured with specific or unique properties. Risk assessment and management of engineered nanoparticles is still in infancy and guidance on exposure assessment and respiratory protection is limited [14, 15].

Lack of practical and cost-effective technologies to evaluate exposures as well as uncertainty in the risks posed by ultrafine and nanoparticles has spurred an increasing awareness in the occupational health community and a corresponding demand for systematic research and guidance. The respirator certification protocols were developed and adopted prior to ultrafine and nanoparticle risk management possessed the importance it does today. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the existing NIOSH respirator certification protocol from the perspective of its ability to provide users information on filtration in the ultrafine particle size range.

REVIEW OF NIOSH PROTOCOL FOR TESTING FILTRATION AND METHODOLOGY FOR EVALUATION OF THIS PROTOCOL

Overview

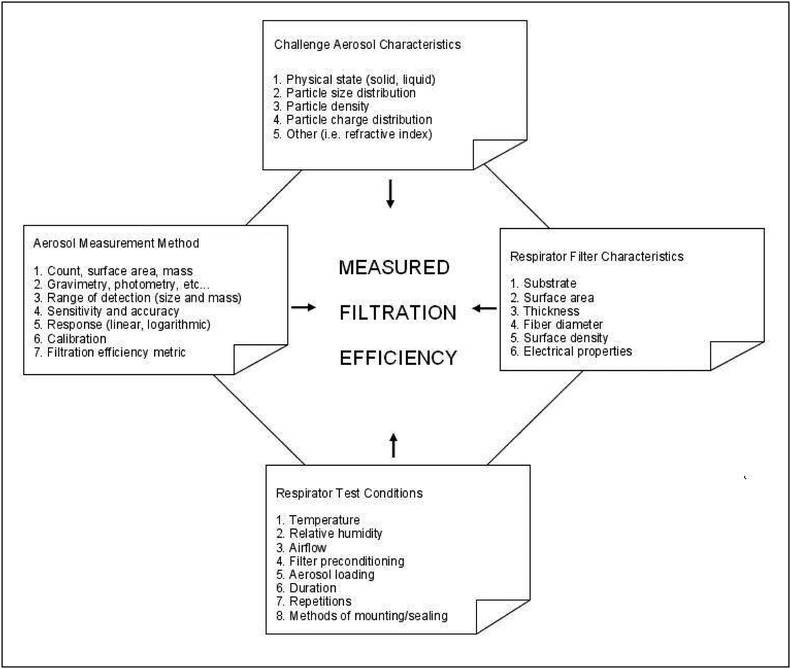

The parameters of a respirator filtration test critically affect the findings on the respirator performance and consequently the practical implications of the test outcome. Four primary determinants of aerosol filtration are the challenge aerosol characteristics, the respirator filter characteristics, the aerosol measurement method, and the test conditions (see Figure 1). Challenge aerosol characteristics include (but are not limited to) the physical state and density of particles, the particle size distribution, and electrical charges. Respirator filter characteristics include the filter substrate, surface area, thickness, fiber diameter, surface density, and fiber electrical charge (for electret filters). Aerosol measurements are generally concerned with the particle count, surface area, mass (or related characteristic such as light scatter); the measurement method is based on a specific principle, such as gravimetry or photometry, and characterized by the limit of detection and other factors. Test conditions are characterized by the temperature, relative humidity, flow, filter preconditioning, loading, test duration, number of test replicates, and procedures chosen for mounting/sealing a filter in a test chamber. Three of these parameters—challenge aerosol particle size distribution, filter electret properties, and challenge aerosol measurement method—were evaluated in this study in order to define the lower boundary of detectable particle size associated with the NIOSH filtration certification test.

FIGURE 1.

Factors influencing respirator filter test results

The methods to perform this evaluation are summarized here. The physical characteristics of challenge aerosols used in the NIOSH respirator certification protocol were reviewed. Next, the size-fractioned light-scatter of the NIOSH test aerosols was modeled and aerosol measurement methods for determining filtration efficiency were evaluated with respect to their ability to detect the contribution of all particle sizes present. Finally, strengths and shortcomings of the existing certification aerosol detection methods were reviewed in light of published findings about the most-penetrating particle size (MPPS) for electret filters.

Challenge Aerosols

First, an ideal aerosol for utilizing in testing respirator filtration should be safe to use, easy to generate, measure, maintain a stable challenge concentration, and replicate at different laboratories. Second, its penetration through respirator filters should represent a “very severe” or “worst case scenario” relative to the expected workplace aerosol contaminants. Third, it should be as degrading or more degrading to a filter material than workplace aerosols. No single challenge aerosol fulfills all of these requirements, and filter testing for non-workplace contaminants and environments (i.e., military applications) may need to differ.

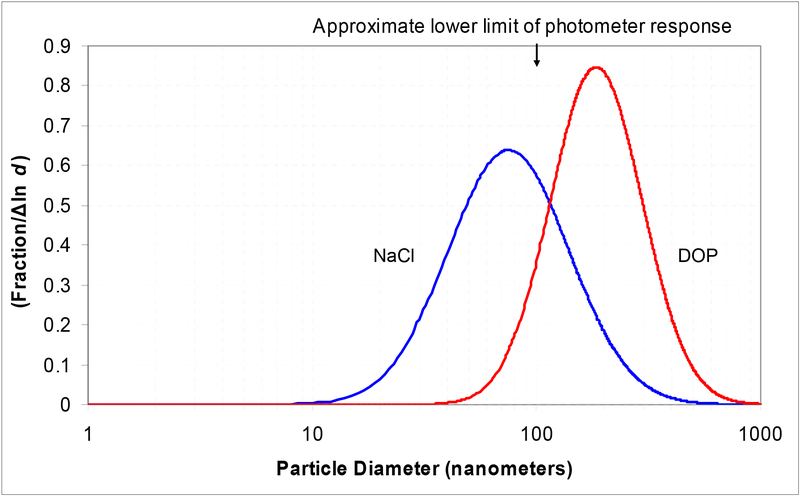

The aerosol utilized by NIOSH to evaluate respirators for use against solid particles is sodium chloride (NaCl) [3]. The test aerosol is required to have a 75 ± 20 nm count median diameter (CMD) and a geometric standard deviation (GSD) of less than or equal to 1.86. Based upon a density of 2.13, it has a mass median aerodynamic diameter of 347 nm [16]. The aerosol that NIOSH utilizes to evaluate respirators against liquid particles is dioctyl phthalate (DOP) [3]. This oil-based aerosol was chosen for its degrading properties and is required to have a CMD of 165 ± 20 nm and a GSD < 1.6. Based upon a density of 0.986, its MMAD is 356 nm [17]. The characteristics of both challenge aerosols are summarized in Table II and Figure 2. Logarithmic distributions theoretically have no upper limit; we assumed an upper bound of 1 μm. In practice, this is a reasonable estimate of the largest particle sizes observed in the certification tests. In the literature, the NIOSH challenge aerosol is often referred to as “0.3 μm in size”, which technically means the mass median aerodynamic diameter discussed here. The above indicated aerodynamic diameter was selected based upon a most penetrating particle size (MPPS) predicted by single fiber filtration theory of mechanical filters, which is applied to respirator filters undergoing the NIOSH testing program [3, 6].

TABLE II.

NIOSH Challenge Aerosol Characteristics for Particulate Respirator Filtration

| Challenge Aerosol | Density | Count Median Diameter (CMD)A | Geometric Std Deviation (GSD) | Mass Median Diameter (MMD)C | Mass Median Aerodynamic Diameter (MMAD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride, NaCl | 2.13 | 75 ± 20 nm | ≤ 1.86 | 238 nm | 347 nm |

| % count distribution:b | % mass distribution:b | ||||

| ± 1 SD (68%) | 40 – 140 nm | ± 1 SD (68%) | 128 – 443 nm | ||

| ± 2 SD (95%) | 22 – 252 nm | ± 2 SD (95%) | 70 – 732 nm | ||

| Dioctylphthalate, DOP | 0.986 | 165 ± 20nm | ≤ 1.60 | 359 nm | 356 nm |

| % count distribution: b | % mass distribution:b | ||||

| ± 1 SD (68%) | 116 – 295nm | ± 1 SD (68%) | 224 – 560 nm | ||

| ± 2 SD (95%) | 73 – 464 nm | ± 2 SD (95%) | 142 – 821 nm | ||

Per 42 CFR 84.181(g), the challenge aerosol CMD must be within +/− 20 nm.

Calculated using Hatch-Choate equations [6].

Count and mass distributions differ slightly from those predicted by the logarithmic function due to assumed 1 μm upper particle size.

FIGURE 2.

Challenge aerosol particle size distributions (by count) and photometer limit of detection

The charges carried by the challenge aerosol particles influence filter penetration. The NIOSH challenge aerosols are equilibrated to a bipolar Boltzmann charge distribution, which results in zero net charge. This is commonly referred to as a “charge-neutralized” aerosol. Since individual particles of a charge-neutralized aerosol may carry a positive or negative charge, this is an example of a “very severe” rather than a “worst case” test condition. A worst case condition, although not as applicable to workplace aerosols, occurs when both individual particles and the aggregate aerosol possess no net charge [5, 18].

Aerosol Measurement Method

An ideal aerosol measurement method for testing filters should be rapid, accurate and reproducible, maintain calibration, and cover an appropriate particle size range that includes the most penetrating particle size (MPPS) for all tested filter materials. It seems that none of the currently available measurement methods meet all the above criteria.

The NIOSH testing protocol utilizes two forward-light scattering photometers to simultaneously measure aerosol concentrations before (“upstream”) and after (“downstream”) the respirator. Photometers measure the amount of light scattered by an assemblage of aerosol particles, which for certain particle sizes is proportional to aerosol mass [19]. For a given wavelength of incident light (λ), scattering angle, and particle index of refraction, the flux of scattered light by an assemblage of particles (R) is proportional to concentration and depends on the particle size distribution according to the following relationship [19]:

| (1) |

Here cn is the particle number concentration, f(dp) is the particle size distribution probability density function, and Pλ is the single-particle flux of scattered light. The NIOSH filter testing protocols utilize a specific incident light wavelength, particle indices of refraction, and scattering angle, which are the same for upstream and downstream measurements. Therefore, we will focus on the effect of particle size on the measurement results.

The certification testing deploys a TSI model 8130 Automated Filter Tester (TSI, Inc., St. Paul, MN), which embeds two forward laser-scattering photometers for upstream and downstream particle concentration measurements. Scatter from the 780 nm wavelength laser light is measured at 45° of incidence. For particle physical diameters less than approximately half the incident light wavelength (1/2λ), scatter is proportional to dp6 and increases monotonically with increasing particle size [19]. For the NIOSH challenge aerosol, this includes particles up to ~380 nm in physical diameter. For aerosol particles larger than 380 nm (>1/2λ), scatter is overestimated by this relationship, and more sophisticated methods are required [19]. As the aerosol concentrations upstream and downstream of the filter are indicated by the photometer output voltages, percent filter penetration is calculated as the ratio of these concentrations, corrected for a zero background, multiplied by one-hundred:

| (2) |

Note that P, which represents penetration in this equation, is separate and distinct from the earlier defined Pλ.

Photometry is extremely useful as it provides a rapid way to estimate upstream and downstream aerosol concentrations when testing the filter performance. However, there are practical limits of photometry associated with the ultrafine particle size range. Generally, 100 nm is considered the smallest particle diameter that measurably contributes to a photometer signal [19, 20]. Additionally, 100 nm is the lower limit of particle size detected in the device utilized in the NIOSH test protocol [21]. This limit is imposed by a combination of background light-scatter from the fluid medium, light sensitivity limits due to the required detection range of photometers, and limits in the photometer light-sensing optics. Figure 2 superimposes this lower limit of detection on the test aerosol particle size distributions. From this figure, it is apparent that most of the NaCl particles and a considerable portion of the DOP particles (by size) may not contribute to the photometric concentrations used to certify respirator filtration.

To determine the contribution to light scatter available for photometer detection by size fraction, we modeled the single particle light scatter, Pλ, for each test aerosol based upon its upstream particle size distribution and physical characteristics using MiePlot version 3.5.01 (Philip Laven, Geneva Switzerland). This software allows for modeling of various user-defined aspects of optical and electromagnetic scattering by particles in accordance with Mie theory [22]. The modeling parameters included challenge aerosol refractive index (NaCl: 1.544, DOP 1.485), medium refractive index (1.0), light scatter angle (45°), and incident light wavelength of 780 nm with perpendicular polarization [16,17]. The model output was the relative intensity of scattered light at 45°.

For the model, the scattering particles were assumed to be homogenous spheres. This is very nearly the case for the DOP aerosol particles, but not for the NaCl particles, which are a face-centered cubic crystal structure. Previous studies have shown that Mie scattering provides a reasonable estimate of light scatter for non-spherical particles in certain circumstances. Perry et al. studied light scatter of aerosolized salt particles up to 1 μm in diameter and observed that light scatter in the forward direction was relatively independent of shape for particles with a size parameter up to 3 [23]. For the NIOSH sodium chloride challenge aerosol, this observation would apply to particles smaller than 745 nm.

More recent work by Chamaillard et al. compared the differences in modeled light scatter estimates for sea salt crystal aerosol particles from ~ 100 nm to 2 μm in size using Mie theory and discrete dipole approximation (DDA) [24]. Discrete dipole approximation utilizes a volume integral equation to describe the interaction of electromagnetic waves and objects and is applicable to estimating scatter from non-spherical particles. Chamaillard et al. observed little or no difference in scatter between the two models for particles smaller than 300 nm. They also reported that Mie theory underestimated particle scatter by ~ 10% for salt particles greater than 800 nm. Thus, our assumption of spherical NaCl particles seems reasonable for the purpose of this investigation and did not have essential impact on our observations.

After multiplying the modeled single-particle flux of scattered light (Pλ) with the aerosol particle size density function, the size-fractioned contribution to light scatter was obtained for each challenge aerosol. These values were then summed over the challenge aerosol particle size distributions up to one micrometer:

| (3) |

The above cumulative scatter function was plotted with the challenge aerosol count and mass cumulative functions to provide a side-by-side comparison of cumulative count, mass, and light-scattering response for the two challenge aerosols.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

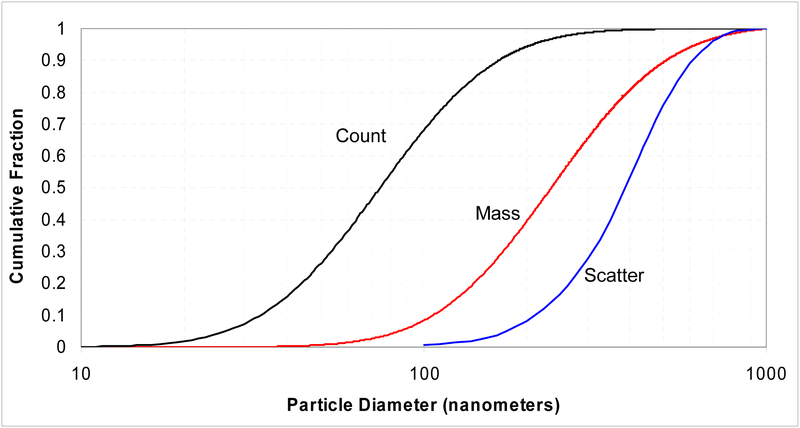

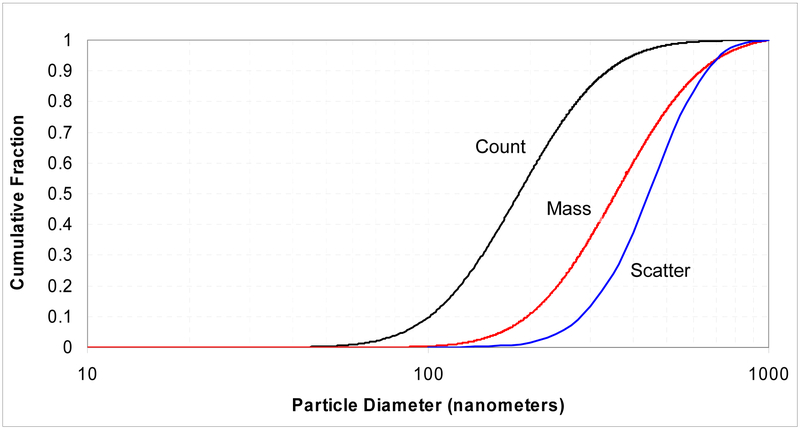

The results of our analysis are shown in Figures 3a and 3b. In addition, Table III presents a summary of the size-fractioned contributions to count, mass and scatter for each NIOSH challenge aerosol.

FIGURE 3a.

NaCl challenge aerosol cumulative fractions: count, mass, light Scatter

FIGURE 3b.

DOP challenge aerosol cumulative fractions: count, mass, light scatter

TABLE III.

Percent Contribution by Size for Two Challenge Aerosols

| Particle Size Range | NaCl Test Aerosol (%)A | DOP Test Aerosol (%)A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | Count | Mass | Scatter | Count | Mass | Scatter |

| 0 – 100 | 68 | 8 | 0.6B* | 10 | 0.3 | <0.01B |

| 100 – 200 | 26 | 31 | 8 | 47 | 11 | 2 |

| 200 – 300 | 4 | 26 | 20 | 28 | 25 | 12 |

| 300 – 400 | 1 | 15 | 25 | 10 | 24 | 24 |

| 400 – 500 | 0.2 | 9 | 23 | 3 | 17 | 28 |

| 500 – 600 | 0.07 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 10 | 19 |

| 600 – 700 | 0.02 | 3 | 7 | 0.4 | 6 | 10 |

| 700 – 800 | <0.01 | 2 | 3 | 0.1 | 3 | 5 |

| 800 – 900 | <0.01 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.05 | 2 | 1 |

| 900 – 1000 | <0.01 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.4 |

Columns may not add to 100% due to rounding error.

Scatter values for 0 – 100 nm are theoretical; scatter from ultrafine particles is poorly detected by photometers

The figures allow determining the count or mass of the challenge aerosols relative to light scatter. It is seen from Figure 3a and Table III that NaCl particles smaller than 100 nm comprise 68% by count and about 8% by mass, but essentially do not contribute to the light scatter available for photometer detection. On the other hand, the largest 0.3% of particles by count and largest 21% by mass provide half the light scatter. Approximately 80% of the light scattering is provided by particles 270 nm and larger.

For DOP, Figure 3b and Table III show a similar result: ultrafine particles of DOP which comprise 10% of the count and about 0.3% of the mass have essentially no contribution to light scatter, while the largest 3% of particles by count and largest 30% by mass provide half the light scatter. Approximately 80% of the light scattering is provided by DOP particles 350 nm and larger.

The analysis indicates that the NIOSH certification test protocol (as directed by 42 CFR 84.181) effectively does not measure the contribution to filter penetration made by particles in the ultrafine size range. Particles less than 100 nm in size are present in both challenge aerosols; however, these particles essentially do not contribute to the photometer signal used for measuring the aerosol concentration. Therefore, the certification protocol—as it is now administered—has limited ability to provide users with information on the respirator filter efficiency against ultrafine particles. This finding seems to be of particular importance due to the uncertainties of health effects associated with environmental ultrafine aerosol particles and engineered nanoparticles (<100 nm). Workplace risk management of potential occupational hazards from engineered nanoparticles is an area of ongoing research. NIOSH has identified respiratory protection as a critical topic area with respect to knowledge gaps about nanotechnology and occupational health [25].

The existing certification test may not assess filtration efficiency for the particle sizes that represent the ‘worst case scenario” in terms of collection by respirator filters with electret properties (i.e., exhibit the highest penetration). The MPPS for a specific filter system is determined by several factors, including airflow, fiber charge density, and aerosol particle charge distribution [6, 7, 18, 26, 27]. The NIOSH presumption of a most penetrating size of approximately 300 nm (MMAD) may not hold for electret filters under NIOSH test conditions. A summary of evidence in support of this is shown in Table IV and discussed here. It has been shown with NaCl challenge aerosol that peak aerosol particle penetration through polypropylene electret filter material may occur at particle diameters much less than 300 nm. The MPPS, which has been shown to decrease with increasing filter face velocity, appears to be consistently less than 100 nm for aerosols in uncharged and Boltzmann charged conditions. Baumgartner and Loffler [28] evaluated two types of electret filters against 20–250 nm NaCl particles in charge equilibrium. For split-type fibrous filters, peak penetrations occurred at approximately 30 nm while they were observed at ~ 70 – 80 nm for the electrostatically spun filter. Lathrache and Fissan [29] tested three types of commercially available electret filters against the Boltzmann-charge-equilibrated NaCl and diethylhexyl-sebacate oil (DES) aerosols with a particle diameter of 20 nm to 1 μm at varying face velocities. Penetration was observed to have a bimodal dependence upon particle size, with a MPPS below 100 nm in six of eight test conditions. Kanaoka et al. [26] evaluated a rectangular fiber electret filter against NaCl aerosol particles ranging from 20 to 400 nm in various charge states. The observed MPPS of uncharged and equilibrium-charged particles was less than 100 nm. Oh et al. [30] performed a numerical simulation of single fiber filtration efficiency of a unipolar charged fiber against particles smaller than 1 μm and compared results to laboratory measurements. Using a semi-empirical approach, the authors incorporated simulation of filter deposition by mechanical and electrical means. The model—being in agreement with experimental data—predicted a MPPS of ~ 85 nm.

TABLE IV.

Summary of Studies: Electret Filter Penetration and Most-Penetrating Particle Size

| Study | Filter/Respirator PropeirtiesA | Challenge Aerosol (Charge Condition) |

vfB (cm/s) |

MPPSC (nm) | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | a |

df (Mm) |

L (mm) |

q or σ | |||||

| Baumgartner & Loffler, 1986 | Split fiber | psf = 250 g/m2 | Not provided | NaCl, 20 – 250 nm (Boltzmann) |

10 | < 100 | Filter properties not provided | ||

| Spun fiber | pSf = 30 g/m2 | ||||||||

| Lathrace & Fissan, 1986 | Split fiber | 0.042 | 30 | 5 | 2e-4 – 5e-4 C/m2 | NaCl, 20 – 189 nm DES, 140 nm - 1 μm (Boltzmann) |

2 – 30 | < 100 | MPPS > 100 nm in 2 of 6 test conditions |

| Spun fiber | 0.035 | 5.2 | 1 | 8e-3 – 0.2 nC/m | |||||

| Kanaoka et al., 1987 | PP | 0.031 | ~24* | 4 | 34.2 nC/m | NaCl, 20 – 400 nm, (Uncharged, Boltzmann) |

5 – 200 | <50 | *Rectangular fibers |

| 0.075 | 5 | ||||||||

| Stevens & Moyer, 1989 | Commercially available dust/mist, paint/lacquer/enamel/mist, dust/fume/mist, and high efficiency (HE) respirator filters; filter materials: wool, wool resin, electrostatic felt, felt resin, fiberglass | NaCl,30 – 240nm; DOP, 30 – 300 nm (Boltzmann) |

Q = 16 – 85 L/min | 55 – 120 | MPPS of all tested HE filters 90 – 175 nm | ||||

| Brosseau etal., 1989 | 10 commercially available dust/mist respirators filters; 9 were combined resin-impregnated wool and PP felt, 1 was PP | Latex spheres, 102 nm − 2.02 μm (Boltzmann) |

55.3 – 74.8 | ≤ 102 | Q = 2.7 L/min; filter surface area range: 36.1 – 48.8 cm2 | ||||

| Fardi & Liu, 1991 | 1 mechanical dust/mist and 2 electret dust/mist or dust/mist/fume respirator filters | NaCl, DOP 35 nm - 4 μm (Boltzmann) |

Q = 16, 32,45 L/min | ~ 100 | Face velocity or filter surface area not provided | ||||

| Martin & Moyer, 2000 | 6 commercially available models of FFR: 3 N95, 1 N99, 1 R95, 1 P100 | NaCl, DOP ~ 25 – 400 nm (Boltzmann) |

Q = 85 L/min | 50 – 100 | Aerosols complied with 42 CFR 84.181; filter surface area not provided | ||||

| Oh et al., 2002 | Spun filter | 0.04 | 9 | 1.44 nC/m | NaCl (Boltzmann) |

10 | ~ 85 | Numerical simulation; good agreement with Baumgartner & Loffler | |

| Balazy et al. 2006a | PP FFR | 0.069 | 7.84 | 1.77 | 13 – 14nC/m* Not provided |

NaCl, ~ 10 – 600nm (Boltzmann) |

4.5, 12.9 | 40 – 50 | 2 models of N95 FFR; *q was estimated |

| PP FFR | 0.091 | 7.19 | 0.35 | 3.7, 10.6 | |||||

| Balazy et al 2006b | Same as Balazy et al. 2006a. | MS2 bacteriophage, ~30 – 80 nm (Boltzmann) |

4.5, 12.9 | 40 – 60 | Same as Balazy et al. 2006a. | ||||

| 3.7, 10.6 | |||||||||

| Richardson et al., 2006 | Commercially available devices: 2 N95 FFR, 2 P100 FFR, 2 N95 cartridges, 2 P100 cartridges | NaCl, DOP 20 nm - 3.02 μm; PSL.7–2.9 μm (Boltzmann) |

0.7 – 60 See comments | 50 – 100 | MPPSfor P100> 100 nm; cyclic (40 – 135 L/min) and constant flow (42.5 – 180 L/min) test conditions | ||||

| Rengasamy et al., 2007 | 5 commercially available models of N95 FFR | NaCl 20 – 400 nm (Boltzmann) |

Q = 85 L/min | 40 | Filter surface area not provided | ||||

PP = polypropylene; α = filter packing density; df = fiber diameter; L = thickness; q (nC/m) or σ (C/m2) = charge density; ρsf = surface density.

Vf = filter face velocity; provided where given or can be calculated from data provided in study; Q = volumetric flowrate.

MPPS = most-penetrating particle size.

In addition to testing filter materials, evaluations have been conducted specifically with respirators utilizing electret filters. Brosseau et al. [31] evaluated the collection efficiency of 10 electret dust/mist filters against latex spheres 102 nm to 2 μm in size at a Boltzmann charge distribution. Peak penetration for all filters was observed to occur at the smallest test particle size of 102 nm; results suggested a MPPS equal to or less than 102 nm. Stevens and Moyer [7] tested various types of air-purifying respirator filters against NaCl and DOP aerosols in Boltzmann charge distribution with a particle size ranging from 30 to 300 nm at varying face velocities. Peak penetration was observed to be below 100 nm for all filter types, except for the tested high efficiency (HE) filters—a precursor designation to the current N or P-100 type filters. Fardi and Liu [32] evaluated several models of filtering facepiece respirators (FFR) against charge-neutralized NaCl and DOP aerosols from 35 nm to 4 μm in size. Those respirators with electret properties showed peak penetrations at approximately 100 nm while those without were between 300 and 400 nm. More recently, Martin and Moyer [27] studied the size-fractioned filtration efficiency of various FFR’s against both NIOSH certification test aerosols before and after removing the filter electret charge. They observed that removing the electret charge resulted in significantly higher penetration and a shift in the MPPS from 50–100 nm to >250 nm. Our team at the University of Cincinnati studied the size-fractioned penetration of aerosolized NaCl particles and MS2 bacteriophage virions with a Boltzmann charge distribution through N95 filtering facepiece respirators and observed a MPPS < 100 nm [33,34]. Richardson et al. observed similar results when testing N95 FFR’s and cartridges under varying constant and cyclic flow conditions using neutralized NaCl, DOP, and MS2 bacteriophage aerosols [35]. Lastly, NIOSH researchers recently published a study of size-fractioned N95 FFR penetration using Boltzmann-charged NaCl aerosol 20 to 400 nm in size. They consistently observed a MPPS of approximately 40 nm [36].

According to conventional mechanical filtration theory [6], a NaCl particle with a physical diameter of ~65 nm equates to a MMAD of ~300 nm (which is the currently accepted MPPS). It is important to note that for electret filters the aerosol filtration in the ultrafine size range is governed by the physical particle diameter rather than the aerodynamic diameter. This is supported by the observation that aerosols at or near unit density, including paraffin, DOP and DES oils, polystyrene latex (PSL), and MS2 bacteriophage virus, also show a MPPS less than 100 nm for electret filters, as discussed above.

There are two primary findings of this study. First, our analysis shows limitation of the 42 CFR 84.181 respirator certification protocol as it is currently implemented, which does not assess filtration of ultrafine particles. The particles <100 nm essentially do not contribute to the light scatter available for photometer detection and those between 100 and 200 nm contribute rather little, so that the photometer-measured filtration efficiency is not determined for the above fractions. Second, based upon a review of the existing literature, the most penetrating particles for electret filters appears to belong to the ultrafine size fraction when challenged with an aerosol with a Boltzmann charge distribution. The contribution to light-scatter determined in our analysis is dominated by particles larger than 200 nm in both test aerosols (NaCl and DOP) while representing 6% of the NaCl and 43% DOP particles by count. According to Martin and Moyer [27], quantifying filter penetration by count methods will “always be equal to or exceed a photometrically determined value.” The results of this study provide one explanation for this: light-scatter is dominated by the larger particle sizes in the test aerosols, and those particles most likely to penetrate the filter are not measured by photometric means for electret filters.

The particle size fraction <200 nm, for which the limitations of the existing respirator testing protocol were demonstrated, can represent various workplace aerosols, including welding fume, diesel particles, viruses or viral droplet nuclei, bioaerosol fragments, and engineered nanoparticles. The filter certification via photometry seems to be most appropriate for the respirators used against aerosol hazards with mass-based exposure metrics. Research has suggested that as particle size decreases, particle surface area or count becomes a better predictor of health effects than aerosol mass [14]. Using photometry for filter testing implies a greater toxicological importance to protect users from particles with greater mass. The concept that “more mass means greater health effects” is no longer axiomatic within industrial hygiene practice. Given the wide range of occupational aerosols, it may be that no single aerosol detection method can serve all needs. Particle count may be more appropriate than photometric methods when testing respirator filters for use against certain hazards. This approach would be able to detect and enumerate particles smaller than 100–200 nm and commercial technology for this does exist. To ensure a “worst case” testing scenario—in terms of the ability to detect the most-penetrating particle size—a count-based method of aerosol detection would appear to be preferable.

Estimating ultrafine particle penetration in conjunction with the existing respirator certification protocol may be possible using one of two strategies: 1) modeling that would require using proprietary filter specification data, or 2) additional data collection to establish a reliably predictive correlation between penetration above and below 100 nm. This last strategy is promising as shown recently by Rengasamy et al. (36). In their study, penetration of five N95 respirator filters using the NIOSH certification protocol was plotted against count-based penetration of 40 nm monodisperse particles and the relationship described using regression. They showed that 1) the relative performance of respirators was similar for particles above and below 100 nm among the respirators tested, and 2) a descriptive relationship to predict respirator performance below 100 nm using the existing NIOSH protocol data may be possible. However, significant additional study would be required to derive a reliably predictive relationship for filter cartridges and facepieces in each filter class. Consideration should be given to pursuing this approach further.

CONCLUSIONS

The physical characteristics of aerosols used in the current NIOSH respirator certification/testing protocol were reviewed. According to the protocol, filtration efficiency is determined by measuring the aerosol concentrations upstream and downstream of a filter using a forward light-scattering photometer, which is capable of adequately measuring light scatter of particles significantly above 100 nm. The presently accepted protocol has limited ability to measure the contribution of smaller particles, especially in the ultrafine fraction (<100 nm). The latter include the particles which have been shown to exhibit the highest penetration through electret filters under NIOSH test protocol conditions. Additionally, the information provided by the certification test does not allow evaluating how penetration varies based upon particle size. We conclude that while the NIOSH certification is effective at determining filtration efficiency against the majority of workplace aerosols, it is generally limited to providing respirator users performance data for particles greater than about 100 nm in physical diameter.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was partially supported by NIOSH ERC Pilot Project Research Training Program Grant No. T42/OH008432–02 through the University of Cincinnati Education and Research Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Held Bruce J.: History of Respiratory Protective Devices in the U.S, University of California, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, California, W-7405-Eng.−48, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 2.“Mineral Resources,” Code of Federal Regulations Title 30, Part. 11, 1983. pp. 7–71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.“Respiratory Protective Devices,” Code of Federal Regulations Title 42, Part. 84, 1995. pp. 30335–30404. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer ES and Stevens GA: “Worst case” aerosol testing parameters: II. efficiency dependence of commercial respirator filters on humidity pretreatment. AIHAJ 50:265–270 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyer ES and Stevens GA: “Worst case” aerosol testing parameters: III. Initial penetration of charged and neutralized lead fume and silica dust aerosols through clean, unloaded respirator filters. AIHAJ 50:271–274 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinds WC: Filtration In Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. pp182–205. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens GA and Moyer ES: “Worst case” aerosol testing parameters: I. Sodium chloride and dioctyl phthalate aerosol filter efficiency as a function of particle size and flow rate. AIHAJ 50:257–264 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent JH, and Clement CF: Ultrafine particles in workplace atmospheres. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 358:2673–2682 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson K, Stone V, Clouter A, Renwick L, MacNee W: Ultrafine particles. Occup Environ Med. 58:211–216 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Löndahl J, Pagels J, Swietlicki E, Zhou J, Ketzel M, Massling A, et al. : A set-up for field studies of respiratory tract deposition of fine and ultrafine particles in humans. J Aerosol Sci. 37: 1152–1163 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong S and Jaques K, Jaques PA: Respiratory dose of inhaled ultrafine particles in healthy adults. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 358:2693–2705 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho S-H, Seo S-C, Schmechel D, Grinshpun SA, and Reponen T: Aerodynamic characteristics and respiratory deposition of fungal fragments. Atmos Env. 39:5454–5465 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morawska L: Droplet fate in indoor environments, or can we prevent the spread of infection? Indoor Air 16:335–347 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J: Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. EHP 113:823–839 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Approaches to Safe Nanotechnology: An Information Exchange with NIOSH. Draft (2006). [Online] Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/nanotech/safenano/ (Accessed August 30, 2007).

- 16.National Library of Medicine: Sodium chloride, CAS 7647-14-5. Hazardous Substances Database. [Online] Available at http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov (Accessed October 15, 2006).

- 17.National Library of Medicine: Di-n-octyl phthalate, CAS 117-84-0. Hazardous Substances Database. [Online] Available at http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov (Accessed October 15, 2006).

- 18.Hinds WC: Electrical Properties In Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. pp 316–348. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebhart J: Optical direct reading techniques: light intensity systems In: Baron PA, Willeke K, editors. Aerosol Measurement. Principles, Techniques and Applications. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 2001. pp. 419–454. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinds WC: Optical properties In Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. pp 349–378. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pui DYH and Chen D-R: Direct-reading instruments for analysis of airborne particles In Air Sampling Instruments for Evaluation of Atmospheric Contaminants, 9th ed. Cohen BS and McCammon CS(eds.) Cincinnati: ACGIH, 2001. pp 377–414. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohren CF, Huffman DR: Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. New york: Wiley Interscience, Inc., 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry RJ, Hunt AJ, Huffman DR: Experimental determinations of Mueller scattering matrices for non-spherical particles. Applied Optics 17:2700–2710 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamaillard K, Jennings SG, Kleefeld C, Ceburnis D, and Yoon YJ: Light backscattering and scattering by non-spherical seal-salt crystals. J Quant Spec & Rad Transfer. 79–80:577–597 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Nanotechnology Research Program: Strategic Plan for NIOSH Nanotechnology Research - Filling the Knowledge Gaps. Draft. September 28, 2005 [Online] Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/nanotech/strat_planINTRO.html (Accessed August 30, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanaoka C, Emi H, Otani T, Liyama T: Effect of charging state of particles on electret filtration. Aerosol Sci Tech. 7:1–13 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin SB, and Moyer ES: Electrostatic respirator filter media: Filter efficiency and most penetrating particle size effects. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg 15: 609–617 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumgartner HP, and Loffler F: The collection performance of electret filters in the size range 0.01 μm–10 μm. J. Aerosol Sci. 17:438–445 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lathrache R, and Fissan H. Fraction penetrations for electrostatically charged fibrous filters in the submicron particle size range. Part Charact. 3:74–80 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh Y-W, Jeon K-J, Jung A-I, Jung Y-W: A simulation study on the collection of submicron particles in a unipolar charged fiber. Aerosol Sci Tech. 36:573–582 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brosseau LM, Evans JS, Ellenbecker MJ, Feldstein ML: Collection efficiency of respirator filters challenged with monodisperse latex aerosols. AIHAJ. 50:544–549 (1989) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fardi B, and Liu BYH: Performance of disposable respirators. Part Part Syst Charact. 8:308–314 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balazy A Toivola M, Reponen T, Podgorski A, Zimmer A, and Grinshpun SA: Manikin-based performance evaluation of N95 filtering-facepiece respirators challenged with nanoparticles. Ann Occ Hyg. 50:259–269 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balazy A, Toivola M, Adhikari A, Sivasubramani S, Reponen T, and Grinshpun SA: Do N95 respirators provide 95% protection level against airborne viruses, and how adequate are surgical masks? Am J Inf Control. 34:51–57 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson AW, Eshbaugh JP, Hofacre KC., and Gardner PD: Respirator filter efficiency testing against particulate and biological aerosols under moderate to high flow rates. U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center Report ECBC-CR-085 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rengasamy S, Verbofsky R, King WP, Shaffer RE: Nanoparticle penetration through NIOSH-approved filtering-facepiece respirators. J Int Soc Resp Prot. 24:49–59 (2007). [Google Scholar]