In the current issue of Acta Physiologica, Yasumatsu et al. addressed whether oral perception of dietary lipids constitutes a discrete basic taste modality [1]. The sense of taste helps the body discriminate between beneficial versus toxic and spoiled food to ensure survival by covering daily nutrient needs and preventing poisoning. Taste not only informs the body of whether food can be ingested, but also prepares the body for processing the incoming food [2]. Until the early 21st century, four basic taste modalities were commonly accepted: sweet, bitter, salty, and sour. Although first described in 1909, a fifth basic taste modality, umami, was finally recognized in 2002, when a receptor was identified in human and rodent taste buds. Umami, the taste of glutamate and nucleotides, is in protein rich foods such as soy and fish sauce, seaweed, tomatoes, meats, and aged cheeses. While sweet, umami and low concentrations of salt are attractive to humans, and bitter, sour and high concentrations of salt are generally avoided, an acquired attraction to bitter and sour can develop in life (e.g. coffee, beer, lemon, sour candies, etc.). In the past 20 years, the taste of fat or “oleogustus” has been suggested as a sixth basic taste modality, but the qualification of taste bud-mediated fat detection as a true taste modality has remained a subject of debate. Taste is defined as the conscious perception of food compounds that bind to specific receptors located on the apical membrane of taste bud receptor cells in the oral cavity and oropharynx [2]. Binding of the nutrients triggers an intracellular signaling cascade in taste receptor cells leading to the release of neurotransmitters onto gustatory afferent fibers of the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerves. Individual taste cells generally express receptors for a single taste modality, i.e., sweet, bitter, or umami, and the nerve fibers that innervate those cells respond best to stimuli of that modality [3]. These highly tuned fibers provide a distinct pathway to the brain, which is thought to underlie the coding of that taste quality, unique and distinct from the others. Dietary lipids are detected orally via texture and smell, as well as in the gut via post-ingestive cues. However, when somesthetic, olfactory and post-ingestive cues are minimized, rodents still prefer lipids over control solutions, and human subjects can detect small concentrations of lipids, suggesting a gustatory dimension to fat perception. Although dietary lipids are composed mostly of triglycerides, free fatty acids seem to be the cue responsible for the orosensory perception of lipids. The lingual lipase hydrolyzes triglycerides into non-esterified fatty acids, thereby increasing fatty acid concentration in the saliva and leading to lower fat perception thresholds. Interestingly, transection of the glossopharyngeal and chorda tympani nerves results in a loss of the preference and of conditioned taste aversion (consumption associated with illness induced by injection of lithium chloride) for fatty acids in rodents. Further, stimulation of the tongue with free fatty acids elicits responses in the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal, suggesting that taste receptors on the tongue mediate these responses [4]. However, does the taste of fat represent a unique modality, or do fatty acids simply modulate the responses to other appetitive tastants such as sweet or umami stimuli? Here, Yasumatsu and collaborators aimed to uncover whether coding of oral fat perception is mediated by clusters of lipid-specific fibers, which would strengthen the concept of fat as a sixth primary taste quality. They used single fiber recordings of the chorda tympani nerve and behavioral assays to investigate whether fatty acids elicit a specific taste quality. Further, they investigated the role of GPR120, a G protein-coupled receptor expressed in mouse and human taste buds, in lingual fat perception [1]. Although recording from single gustatory nerve fibers in mice is a challenging technique, they convincingly demonstrate for the first time that specific nerve fibers, so-called “F-type fibers”, are dedicated to the transmission of fatty acid signals from taste buds to the brain in mice. Activation of F-type fibers upon lingual stimulation with lipids is significantly diminished, albeit not abolished, in GPR120 knockout mice, suggesting GPR120 mediates at least a portion of this response. Interestingly, they found that fatty acids also stimulate subsets of umami and sweet best fibers, M-type and S-type fibers, respectively, and the response of these fibers is also lower in GPR120 knockout mice than controls. In addition, the authors report that conditioned taste aversion for fatty acids tended to be different in GPR120 knock-out mice compared to controls, suggesting that, GPR120 may partially mediate fat taste perception and eating behavior. Furthermore, mice showed some generalization to umami taste stimuli upon conditioned taste aversion to lipids, consistent with the existence of fat/umami-best fibers, in addition to fat-best only fibers, suggesting perceptual similarities between fatty acids and umami taste. The work by Yasumatsu et al. strengthens the argument for the existence of fat taste as a sixth primary taste modality, and their findings support the role of GPR120 as a fat taste receptor involved in transmission of the gustatory signal via fat-specific fibers. This work helps clarify the function of GPR120, which heretofore, had remained unclear and controversial.

The uncertainty surrounding GPR120.

A taste receptor role for GPR120 was first suggested when gustatory nerve responses and preference for fatty acids were reportedly reduced in GPR120 knockout mice compared to controls [5]. However, some subsequent studies failed to replicate these earlier data [6, 7]. In addition, wild-type mice do not display preference for GPR120 specific agonists, and most human subjects do not perceive these agonists. Mechanistically, little is known about signal transduction downstream of GPR120 in taste bud cells. Fatty acids induce calcium responses in isolated mouse and human taste cells, but responses are unaffected in taste cells isolated from GPR120 knockout mice compared to those of control mice. Nonetheless, the calcium response to high concentrations of fatty acids is partially abolished when siRNA targeting GPR120 is transfected [8].

As described above and reported in this issue of Acta Physiologica, elimination of GPR120 did not fully abolish the response of fat-best fibers, fat/sweet-best, or fat/umami-best fibers to oral stimulation with fatty acid, or conditioned taste aversion to fatty acids, or calcium responses to fatty acids, suggesting that other receptors also mediate fat taste and the regulation of eating behavior. Several other potential fatty acid taste receptors have been identified in rodents: Kv1.5, CD36 and GPR40, but only the gustatory functions of CD36 have been studied extensively.

Is CD36 the main fat taste receptor?

CD36, a transmembrane glycoprotein with a high affinity for fatty acids (nM), is expressed in taste buds in mice, rats and humans. While wild-type mice prefer fatty acids over a control solution, CD36 knock-out mice lose the ability to detect the fatty acids, and unlike wild-type mice, do not show conditioned taste aversion to fatty acids [4]. In humans, a single nucleotide polymorphism associated with lower CD36 expression has been identified in subjects whose sensitivity for fatty acid is diminished compared to control subjects, and lower oral lipid sensitivity may be associated with higher food intake and obesity in subjects carrying CD36 polymorphisms [9]. In addition to regulating eating behavior, lingual CD36 seems to impact the cephalic phase of digestion. Stimulation of the tongue with fatty acids in control mice, that had the esophagus ligated to prevent entry of food into the stomach, still elicits the secretion of pancreatobiliary juice, thereby preparing the gut to digest the incoming dietary lipids. This cephalic phase response is abolished in CD36 knockout mice. Further, signal transduction in CD36+ taste cells involves a similar transduction cascade as for sweet, bitter and umami taste [3], including IP3-dependent release of intracellular calcium, and release of transmitters to activate gustatory nerve fibers. Finally, activation of the first gustatory relay in the brainstem, the Nucleus Tractus Solitarius (NTS), following oral exposure to fatty acids is abolished in CD36 knockout mice, further supporting a role for lingual CD36 in the taste perception of dietary lipids [4].

How does GPR120 fit into a CD36-mediated fat taste paradigm?

Much evidence points to CD36 being the main fat taste receptor while the exact function of GPR120 is still under debate due to fewer available and sometimes conflicting data. Stimulation of isolated human taste cells with a high concentration of fatty acids results in an elevated intracellular calcium response which is partially abolished when siRNA targeting CD36 is transfected, or in the presence of GPR120 siRNA, albeit the reduction is smaller than with CD36 siRNA [8]. Interestingly, simultaneous siRNA knockdown of CD36 and GPR120 potentiates the reduction of the fatty acid-mediated calcium response observed in CD36-only or GPR120-only siRNA transfected cells [8], suggesting a cooperative effect of GPR120 with CD36 [4]. One possibility is that, rather than directly controlling fatty acid perception, GPR120 may instead modulate CD36-dependent gustatory fat sensitivity. Stimulation of taste tissues with fatty acids and GPR120 agonists triggers the secretion of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 (GLP1), which is coexpressed with GPR120 in murine taste bud cells. Genetic deletion of GLP1 receptor, which is expressed by gustatory nerve fibers, is associated with changes in sweet, umami and sour taste perception, as well as diminished fat perception, supporting the modulation of CD36 fat detection function by GPR120 (for more details, see [4]).

Closing remarks

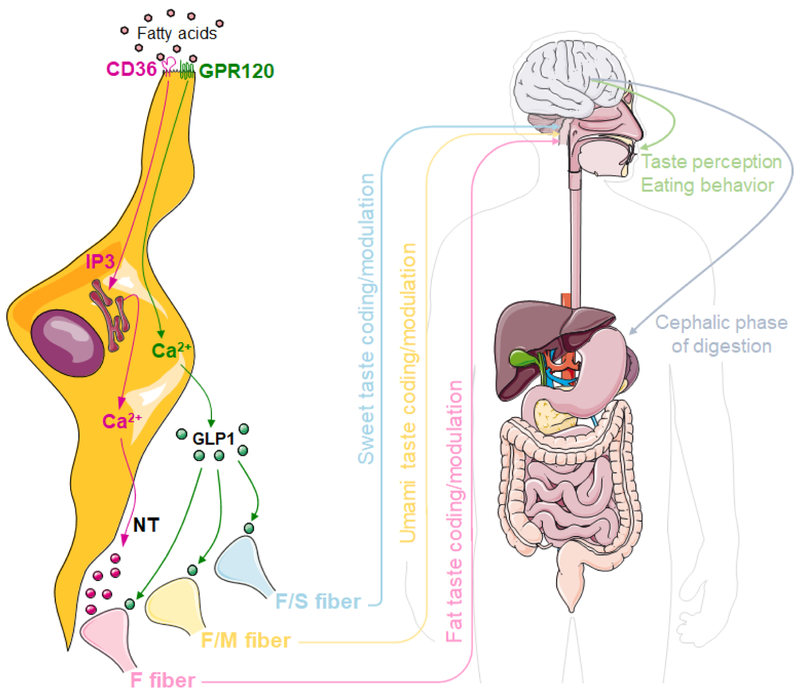

In summary, substantial evidence in rodents and human subjects strongly supports the existence of a unique taste for fat, and Yasumatsu and collaborator’s findings offer new evidence supporting that oral perception of fatty acid is a sixth basic taste quality separate from the historic five primary taste modalities. They demonstrate for the first time the existence of fat-best gustatory nerve fibers that respond distinctively to oral fatty acid stimulation. Comparable to sweet and umami taste, the existence of fat taste is significant for survival by detecting and helping digest high energy food and nutrients that are essential for energy, signaling and structural purpose. However, additional clues are necessary to fully recognize the existence of fat taste; for instance, it is still unclear whether fat taste is consciously perceived and identifiable by human subjects as easily as the other taste qualities. Yasumatsu and collaborators also aimed to address the role of GPR120 in fat taste, but the specific physiological function of lingual GPR120 requires further investigation. Although, this set of data demonstrates a partial involvement of GPR120 in single fat-best gustatory nerve fiber responses to fatty acids, it also supports previous findings that GPR120 is not exclusively required for the gustatory nerve response and fat perception. Altogether, GPR120-dependent stimulation of subsets of sweet and umami fibers upon oral stimulation with fatty acids and the generalization of fatty acid conditioned taste aversion to umami, may support a role for GPR120-mediated lipid detection as a modulator of fat, umami and sweet taste qualities as proposed previously ([4], Figure 1).

Figure 1. Putative function of GPR120 in taste receptor cells.

The detection of fatty acids by CD36 triggers an IP3-dependent mobilization of endoplasmic reticulum calcium (Ca2+), which in turn mediates the depolarization of the cell and the release of neurotransmitters (NT) onto fat-best (F), dual fat/umami-best (F/M) and dual fat/sweet-best (F/S) gustatory nerve fibers. Binding of fatty acids to GPR120 augments intracellular Ca2+ resulting in the secretion of GLP1 onto F-, F/M- and F/S-best nerve fibers to modulate the coding of fat, umami and sweet perception, respectively. Altogether, fat taste regulates taste perception and eating behavior, as well as the cephalic phase of digestion to prepare the gastrointestinal system to digest the incoming food. For clarity purpose, and because both proteins are coexpressed in taste receptor cells, CD36 and GPR120 are represented in the same cell; however, this model may include expression of CD36 and GPR120 in distinct cells. Illustrations modified from Servier Medical Art licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://smart.servier.com/).

Nota bene:

only key original articles pertaining to GPR120 were cited, while the most up-to-date and detailed reviews on taste and fat taste were referenced to comply with the limitation on the number of citations. We invite the reader to refer to [2] and [3] to learn more about the biology of taste, and to [4] and [9] for more detailed information about fat taste, the functions of CD36 and discussions about the possible cooperation of CD36 and GPR120 in the mediation of fat taste.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders to DG (R21DC016131) and to SCK (R01DC012555 and R01DC017679). We thank Drs. Linda Barlow and Tom Finger for helpful comments on the manuscript. Illustrations used in the figure are modified from Servier Medical Art licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://smart.servier.com/).

Footnotes

This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/apha.13246

Conflict of interest: none

References

- 1.Yasumatsu K, Iwata S, Inoue M, Ninomiya Y. Fatty acid taste quality information via GPR120 in the anterior tongue of mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2018;0(ja):e13215 Epub 2018/10/31. doi: 10.1111/apha.13215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslin PA. An evolutionary perspective on food and human taste. Curr Biol. 2013;23(9):R409–18. Epub 2013/05/11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roper SD, Chaudhari N. Taste buds: cells, signals and synapses. Nature reviews. 2017;18(8):485–97. Epub 2017/06/29. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besnard P, Passilly-Degrace P, Khan NA. Taste of Fat: A Sixth Taste Modality? Physiol Rev. 2016;96(1):151–76. Epub 2015/12/04. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartoni C, Yasumatsu K, Ohkuri T, Shigemura N, Yoshida R, Godinot N, et al. Taste preference for fatty acids is mediated by GPR40 and GPR120. J Neurosci. 2010;30(25):8376–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sclafani A, Zukerman S, Ackroff K. GPR40 and GPR120 fatty acid sensors are critical for postoral but not oral mediation of fat preferences in the mouse. American journal of physiology. 2013;305(12):R1490–7. Epub 2013/10/25. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00440.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ancel D, Bernard A, Subramaniam S, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G, Hashimoto T, et al. The oral lipid sensor GPR120 is not indispensable for the orosensory detection of dietary lipids in mice. J Lipid Res. 2015;56(2):369–78. Epub 2014/12/10. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdener MH, Subramaniam S, Sundaresan S, Sery O, Hashimoto T, Asakawa Y, et al. CD36- and GPR120-mediated Ca(2)(+) signaling in human taste bud cells mediates differential responses to fatty acids and is altered in obese mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(4):995–1005. Epub 2014/01/15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu D, Archer N, Duesing K, Hannan G, Keast R. Mechanism of fat taste perception: Association with diet and obesity. Progress in lipid research. 2016;63:41–9. Epub 2016/05/08. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]