Abstract

Ca2+ signals, which facilitate pluripotent changes in cell fate, reflect the balance between cation entry and export. Overexpression of both isoforms of the Ca2+ extruding plasma membrane calcium ATPase 4 (PMCA4) pump in Jurkat T cells unexpectedly increased activation of the Ca2+-dependent transcription factor Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT). Coexpression of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident Ca2+ sensor stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) with the PMCA4b splice variant further enhanced NFAT activity, yet co-expression with PMCA4a depressed NFAT. No PMCA4 splice variant-dependence in STIM1 association was observed. However, Partner of STIM1 (POST) preferentially associated with PMCA4b over PMCA4a, which enhanced rather than inhibited PMCA4 function. Comparing global and near-membrane cytosolic Ca2+ abundance during store-operated Ca2+ entry revealed that PMCA4 markedly depressed near-membrane Ca2+ concentration, particularly when PMCA4b was co-expressed with STIM1. PMCA4b closely associated with both POST and the store-operated Ca2+ channel Orai1. Further, POST knockdown increased near-membrane Ca2+ concentration, decreasing the global cytosolic Ca2+ increase. These observations reveal an unexpected role for POST coupling PMCA4 to Orai1 to promote Ca2+ entry during T cell activation through Ca2+ disinhibition.

Introduction

The regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ is a universal mechanism of signal transduction (1). In non-excitable cells, the primary initiators of Ca2+ signals are phospholipase C (PLC)-coupled receptors, the activation of which leads to inositol trisphosphate (InsP3) production and the Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that is responsible for the initial increase in cytosolic Ca2+. ER Ca2+ store depletion leads to oligomerization and extension of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), driving its migration toward sites of close ER-plasma membrane (PM) apposition where it coordinates the activation of multiple signaling proteins. While Orai1 is by far the best investigated STIM target (2–5), numerous other PM-localized STIM effectors have been identified including TRPC channels (6–9), adenylate cyclase (10–12), CaV1.2 (13, 14) and plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase 4 (PMCA4; gene name ATP2B4) (15, 16). While there is strong support for each of these STIM targets individually, there is a paucity of information regarding how these distinct events are coordinated. Partner of STIM1 (POST; gene name SLC35G1) was identified in 2011 as an adaptor protein linking STIM1 to multiple pumps and exchangers (17). In this study, we focused on understanding the role of POST in control of Ca2+ signal generation during T cell activation.

STIM, Orai and PMCA are universally expressed. T cells in particular, the primary focus of this investigation, exhibit profound dependence upon store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) (3, 4). One of the earliest events following antigen presentation is PLC activation and cytosolic Ca2+ elevation (18). Due to the ~20,000-fold difference in Ca2+ concentration observed between the cytosol and both the extracellular milieu and the endoplasmic reticulum, the opening of Ca2+ channels leads to profound spatiotemporal differences in local Ca2+ levels. Hence, the concentration of Ca2+ in the immediate vicinity of an open Ca2+ channel is reflective of the concentration of Ca2+ outside of the cell or within the ER lumen (19, 20). This leads to the existence of short-lived Ca2+ microdomains near the pores of Ca2+ channels that are critical for T cell activation (21, 22). Activation of Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells (NFAT), in particular, was shown to be directly dependent upon Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry (23), although Ca2+ microdomains likely contribute to the activation of other transcription factors and cellular processes (example (24)). However, like most Ca2+ channels, Orai1 is inhibited by Ca2+ (25, 26). Therefore, local Ca2+ elevation presents a unique challenge for processes that require sustained Ca2+ responses. The extent to which Ca2+ clearance mechanisms may relieve Ca2+-mediated channel inhibition has not been established.

T cell activation inhibits PMCA4 activity (15–17, 27), and reduces Ca2+ clearance. The focus of our investigation here on the molecular interactions between STIM1, PMCA4, POST and Orai1 identified context-dependent differences in PMCA4 function in activated T cells. The findings revealed a role for POST in protecting PMCA4 from STIM1-mediated inhibition, thereby coupling PMCA4 to Orai1, which promotes sustainable Ca2+ entry and NFAT activation in Jurkat T cells.

Results

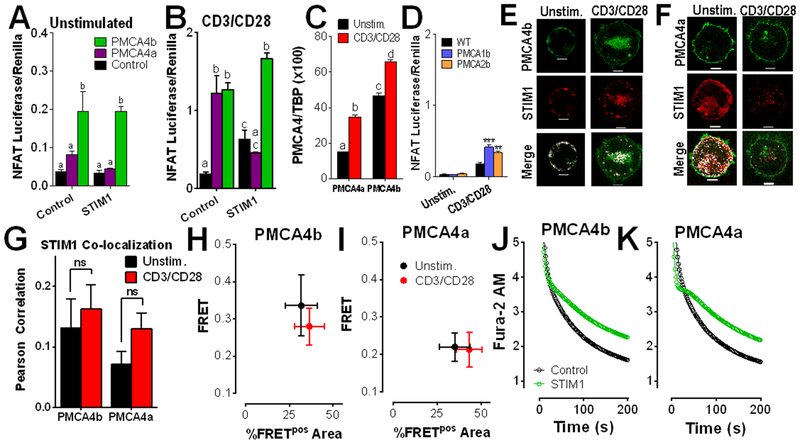

PMCA4 stimulates NFAT activity

In a prior investigation, we showed that PMCA4b inhibition by STIM1 can contribute to NFAT activation (16). Considering that NFAT nuclear translocation is controlled by Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation by calcineurin, this observation was consistent with current thinking; the corollary of this finding would be that increased PMCA4 activity would decrease NFAT activation. However, contrary to this prediction, PMCA4 overexpression has the opposite effect. In resting Jurkat T cells, overexpression of PMCA4b, but not PMCA4a led to an ~4-fold increase in NFAT activation (Fig. 1A). A 5 to 10-fold increase in NFAT activation was observed in Jurkat T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 under all conditions, with expression of either PMCA4a or PMCA4b maximally increasing NFAT activation. While STIM1 expression had no effect on NFAT activity in resting cells (Fig. 1A), this was not the case in activated cells. Hence, STIM1 overexpression stimulated NFAT activation (Fig. 1B). While PMCA4a co-expression failed to further stimulate NFAT activity, co-expression of PMCA4b potently increased NFAT activation in activated T cells (Fig. 1B). There is relatively little information about PMCA4 splice variant expression levels, however, analysis by qPCR revealed that both PMCA4b and PMCA4a are up-regulated following anti-CD3/CD28 treatment, and that PMCA4b is the dominant splice variant in both resting and stimulated cells (Fig. 1C). These observations reveal an unexpected relationship between Ca2+ clearance and NFAT activity. To determine if this effect is unique to PMCA4, NFAT activity was measured in cells overexpressing other PMCA isoforms. Overexpression of either PMCA1b or PMCA2b did not have an effect on resting NFAT levels, while a relatively modest, but still significant increase in NFAT activity was observed in activated cells (Fig. 1D). Considered collectively, these observations reveal an unexpected and counter-intuitive role for PMCA4 and STIM1 in the regulation of NFAT activation. The current study is focused on characterizing this intriguing discovery.

Figure 1: PMCA4 expression increases NFAT activity in a splice variant- and STIM1-dependent manner.

(A and B) Luciferase assay analysis of NFAT activity in Jurkat T cells transfected with vectors encoding NFAT4-IFN-luciferase, Renilla and control, PMCA4a, or PMCA4b, then left unstimulated (A) or stimulated with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 (B) for 6 hrs. Data are means ± SEM from 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (A) Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA; p<0.0001 for PMCA4, p>0.05 for STIM1, and p>0.05 for interdependence between PMCA4 and STIM1. Statistically significant groups are indicated by a, b (p < 0.05). (B) Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA; p<0.0001 for PMCA4, p>0.05 for STIM1, and p<0.0001 for interdependence between PMCA4 and STIM1. Statistically significant groups are indicated by a, b, c (p < 0.05). (C) qRT-PCR analysis of the ratio of PMCA4 to TBP expression in Jurkat T cells stimulated with antibodies against CD3 and CD28, as indicated for 2 hours. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA; p<0.0001 for PMCA4a, p<0.0001 for PMCA4b and p>0.05 for interdependence between PMCA4 isoform expression and CD3/CD28. Statistically significant groups are indicated by a, b, c and d (p < 0.05). (D) Luciferase assay analysis of NFAT activity in Jurkat T cells transfected with vectors encoding NFAT4-IFN-luciferase, Renilla and control, PMCA1b, or PMCA2, then stimulated as indicated. Data are means ± SEM from 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA; p<0.0001 for PMCA expression, p<0.0001 for the effect of CD3/CD28 and p>0.00001 for interdependence between PMCA isoform expression and CD3/CD28. Post-hoc analyses determined the effect of PMCA expression relative to control in unstimulated (p > 0.05), and in cells plated on anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001). (E to G) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of Jurkat T cells co-transfected with STIM1-mCherry (red) and either GFP-PMCA4b (green, E) or GFP-PMCA4a (green, F), and activated as indicated for 2 hours (scale bar = 5 μm). Images (E and F) are representative of >5 independent experiments. Co-localization between STIM1 and PMCA4 is shown in white. Pearson coefficients (G; means ± SEM; 19-63 cells) were calculated across the entire cell. ns, not significant by two-way ANOVA. (H and I) FRET by acceptor photobleaching analysis in Jurkat cells co-transfected with STIM1-mCherry and either GFP-PMCA4b (H) or GFP-PMCA4a (I). Means ± SEM of FRET values>0.1 (FRET+) regions for each cell are plotted on the y-axis, and the percentage of area in which FRET was detected out of the total area photobleached on the x-axis (%FRETpos Area). Data are from >5 independent experiments, n=7-10 cells per condition. (J and K) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of Ca2+ clearance in Fura-2 AM-loaded, thapsigargin-treated Jurkat T cells that were transfected with STIM1-mCherry and either GFP-PMCA4b (J) or GFP-PMCA4a (K), plated on CD3/CD28 antibody-coated coverslips, and exposed to Ca2+ for 2 min before recording in Ca2+-free buffer + EGTA. Resultant Ca2+ clearance (determined from 5-6 independent experiments) is shown as open circles. In addition, data was fit to a biphasic exponential decay model, shown as a line. Representative full-length traces of these experiments are presented in fig. S1; quantitation of Ca2+ clearance dynamics with statistical analysis is provided in table S1.

Activation of Jurkat T cells expressing each PMCA4 splice variant revealed that both splice variants accumulate at the immunological synapse (IS), expanding on previous reports in Jurkat T cells plated on anti-CD3 antibodies (15, 28, 29). Co-expression with STIM1 showed that differences in splice variant function were not due to localization with STIM1 or the IS (Fig. 1, E to G). Additionally, FRET analysis by acceptor photobleaching was performed at sites of STIM1-mCherry and GFP-PMCA4 co-localization. FRET efficiency was plotted against the percentage of the probed area in which FRET was detected (%FRETpos Area). These experiments revealed modestly higher FRET efficiency between STIM1 and PMCA4b vs. PMCA4a, but no significant differences associated with T cell activation (Fig. 1, H and I). These observations demonstrate that STIM1 and PMCA4 are able to constitutively associate and may translocate to the IS upon T cell activation as a complex.

Whether STIM1 regulates PMCA4a activity has not previously been assessed. Cells were transfected with PMCA4 splice variants along with either STIM1 or empty vector before plating on CD3/CD28 antibody-coated coverslips for 2 hours. ER Ca2+ stores were depleted in Ca2+ free buffer containing thapsigargin before the addition of 1 mM Ca2+ for 2 minutes. Ca2+ clearance was measured upon the subsequent addition of Ca2+ free buffer with 100 nM EGTA (Fig. 1, J and K). The latter portion of these experiments is shown in this and subsequent figures; complete traces for this (fig. S1, A and B) and subsequent experiments are provided as supplementary material. As in prior studies (15, 16, 30), Ca2+ clearance was fit to 2-phase exponential decay. Co-expressing STIM1 with either PMCA4b or PMCA4a significantly attenuated the slow phase of Ca2+ clearance (table S1). Therefore, the mechanism by which PMCA4 splice variants differ in the regulation of NFAT activity are not dependent on localization, interaction, or regulation by STIM1. Given prior studies revealing POST as a STIM1- and PMCA4-binding protein with the ability to modulate Ca2+ clearance (17), our investigation assessed the contribution of POST to PMCA4b-specific enhancement of NFAT activation.

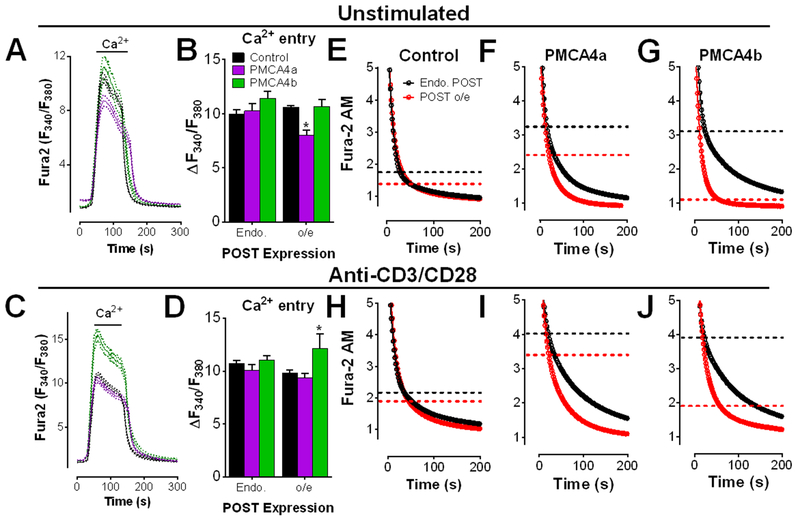

POST promotes Ca2+ entry and clearance when co-expressed with PMCA4

The effect of POST co-expression with either PMCA4 splice variant on Ca2+ entry and clearance was measured in Jurkat T cells. In resting cells, POST significantly attenuated SOCE when PMCA4a was co-expressed, but not in its absence (Fig. 2, A and B). However, this effect was eliminated upon T cell activation. In contrast, POST- and PMCA4b-expressing cells exhibited a modest increase in SOCE (Fig 2, C and D). These data show that POST expression modulates Ca2+ signals in a PMCA4 splice variant-specific manner.

Figure 2: POST accelerates Ca2+ clearance when co-expressed with PMCA4.

(A to J) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of Ca2+ clearance in Fura-2 AM-loaded, thapsigargin-treated Jurkat T cells that were transfected with empty vector or mCherry-POST along with empty vector, GFP-PMCA4a or GFP-PMCA4b. Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated (A, B, and E to G) or CD3/CD28 antibody-coated (C, D, and H to J) coverslips, and exposed to Ca2+ for 2 min before recording in Ca2+-free buffer + EGTA. Representative traces showing Ca2+ entry and clearance in cells transfected with empty vector or PMCA4 ± POST (A and C), and the quantified average peak Ca2+ entry (B and D) are shown. Data are from 5-6 independent experiments per condition. * P<0.05 compared to resting EV cells, by two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. The Ca2+ clearance portions (E to J) of each experiment shown in (A and C) is shown as open circles and was determined from 6 to 13 independent experiments. All data was fit to a biphasic exponential decay model (see tables S2 and S3 for complete analysis). The calculated point of transition between the fast and slow phases for each condition is demarcated by dashed lines. Representative full-length traces of these experiments are presented in fig. S2.

To determine how POST affects PMCA4 function, Ca2+ clearance was examined in cells co-expressing POST and each PMCA4 splice variant. While POST expression alone in unstimulated cells had no significant effect (Fig. 2E; fig. S2A; Table S2), co-expression of either PMCA4a or PMCA4b led to a significant increase in the percentage of Ca2+ clearance found within the slow phase (Fig. 2, F and G; fig. S2, B and C; table S2). However, POST co-expression eliminated this effect in PMCA4b-expressing cells (marked by the dashed lines in Fig. 2; statistics in table S2) and attenuated the effect of PMCA4a expression (Fig. 2F). Hence, whereas STIM1 expression contributes to higher cytosolic Ca2+ by increasing the portion of Ca2+ clearance occurring within the slow phase (Fig. 2, F and G), POST decreases the slow phase portion of clearance, leading to rapid Ca2+ clearance. Furthermore, regulation of Ca2+ clearance by POST is sensitive to PMCA4 splice variant-specific expression.

Examination of POST-mediated control of Ca2+ clearance in activated T cells revealed a very similar relationship (Fig. 2, H to J; fig. S2, D to F). PMCA4 expression led to a substantial increase in the percentage of slow phase Ca2+ clearance independent of splice variant (Fig. 2, I and J; table S3). However, in cells co-expressing POST and PMCA4, Ca2+ clearance shifted toward the fast phase and was significantly accelerated, particularly in PMCA4b-expressing cells (Fig. 2, I and J; table S3). Overall, the effect of POST on Ca2+ clearance was largely independent of CD3/CD28-mediated activation since POST overexpression led to similar outcomes in unstimulated and stimulated cells. However, substantial activation-dependent differences in Ca2+ entry were observed, with the presence of PMCA4b and POST leading to an intriguing increase in SOCE. While decreased SOCE is consistent with accelerated Ca2+ clearance, increased SOCE in activated POST-PMCA4b-expressing cells has not previously been reported and may provide mechanistic insight into why PMCA4b overexpression led to increase NFAT activation (Fig. 1). These experiments implicate a new and unexpected role for POST as a positive regulator of PMCA activity and SOCE.

POST knockdown augments STIM1-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ clearance in activated T cells

To assess the effect of endogenously expressed POST on Ca2+ clearance, Jurkat T cells were transfected with POST siRNA, resulting in ~70% decrease in POST transcripts as measured by qPCR (fig. S3). In contrast with POST overexpression, no significant differences in SOCE were observed with POST knockdown (Fig. 3, A and B). Consistent with prior reports, we observed a modest but statistically significant decrease in τs (Fig 3C; fig. S4, A and B; table S4) (17). However, upon T cell activation, we observed a significant decrease in the fast phase of Ca2+ clearance (marked by the dashed lines; Fig. 3D; fig. S4, C and D; table S4). STIM1 overexpression inhibits Ca2+ clearance independent of activation (15, 16). Whereas POST knockdown had modest effects in unstimulated STIM1-expressing Jurkat T cells (Fig 3E; fig. S4, E and F; table S5), it restored activation-dependence in STIM1-overexpressing cells (Fig 3F; fig. S4, G and H; table S5). Activated T cells transfected with POST siRNA exhibit significant Ca2+-independent differences compared to unstimulated or activated STIM1-expressing cells in both the percentage of Ca2+ clearance within the slow phase and τs (table S5). These observations reveal interdependence between activation-dependent inhibition of Ca2+ clearance and expression of STIM1 and POST, with POST and STIM1 exhibiting competing roles for control of PMCA4 function.

Figure 3: POST knockdown facilitates STIM1-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ clearance in activated T cells.

(A to F) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of Ca2+ clearance in Fura-2 AM-loaded, thapsigargin-treated Jurkat T cells that were transfected with empty vector (A, C, and D) and/or YFP-STIM1 (E and F) along with POST-directed siRNA (blue) or scrambled control (black). Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated (A,C, and D)- or CD3/CD28 antibody-coated (B, E, and F) coverslips, and exposed to Ca2+ for 2 min before recording in Ca2+-free buffer + EGTA. Representative traces showing Ca2+ entry and clearance in cells transfected with POST siRNA or a control RNA (A), and quantitation of the average peak Ca2+ entry in cells transfected and plated as indicated (B). No differences as determined by two-way ANOVA. The Ca2+ clearance portions of each experiment is shown as open circles (C to F). All data was fit to a biphasic exponential decay model (see tables S4 and S5 for complete analysis). The calculated point of transition between the fast and slow phases for each condition is demarcated by dashed lines. Representative full-length traces of these experiments are presented in fig. S3. All traces are the average of 5-6 independent experiments per condition. (G) NFAT activity was measured in Jurkat T cells transfected with scramble control, POST-directed siRNA, or mCherry-POST. Average ± SEM are plotted (n=4-5 independent experiments). Statistical significance was assessed by Two Way ANOVA; p=0.0003 for POST, p=0.0004 for CD3/CD28, and p<0.0001 for interdependence between POST expression and CD3/CD28. Statistically significant groups are indicated by a, b and c (p < 0.05). (H to J) Jurkat T cells were co-transfected with STIM1-mCherry (red) and GFP-POST (green). Colocalization is shown in white. Colocalization (H) was calculated by Pearson coefficient, means ± SEM are shown (n=33-41 cells); scale bar=5 μm. FRET by acceptor photobleaching (I) was performed in cells co-transfected with STIM1-mCherry and GFP-POST. Only regions in which STIM1 and POST colocalized were selected for photobleaching. Means ± SEM of FRET values >0.1 (FRET+) regions (n≥27 cells per condition) are plotted as above in Fig. 1I.

PMCA4 expression leads to increased NFAT activity (Fig. 1). Considering the inverse correlation between POST expression and Ca2+ clearance, we assessed how POST expression might affect NFAT activity (Fig. 3G). While no effect of POST overexpression was observed, POST knockdown decreased NFAT activation in activated, but not resting Jurkat T cells. Considering that POST overexpression had no effect on Ca2+ clearance without PMCA4 overexpression (Fig. 2) and POST knockdown only affected Ca2+ clearance in activated cells (Fig 3, C and D), these observations are consistent with an inverse correlation between Ca2+ clearance and NFAT activity.

To investigate how STIM1 and POST could jointly regulate PMCA4, Jurkat T cells were transfected with STIM1-mCherry and POST-GFP and plated on poly-l-lysine (unstimulated) or anti-CD3/CD28 (no thapsigargin treatment) and examined by confocal microscopy. Substantial co-localization was observed under both conditions, although the localization of both POST and STIM1 was visibly changed by T cell activation (Fig. 3, H and I). We utilized FRET analysis by acceptor photobleaching to determine if activation-dependent regulation of clearance by POST is governed by shifts in STIM1-POST interactions. Focusing specific on sites of colocalization, this analysis revealed direct interaction between STIM1 and POST that was unaffected by plating on anti-CD3/28 antibodies (Fig. 3J). These observations support prior findings that STIM1 and POST interact but do not provide insight into how T cell activation might modulate these associations for control of Ca2+ clearance. Therefore, we examined activation-dependent associations between POST and PMCA4 splice variants.

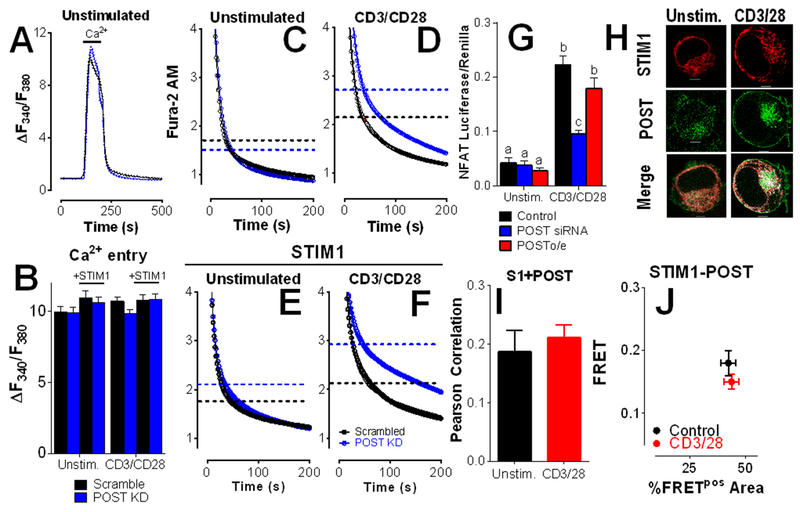

POST has 9 transmembrane domains

There have been no previous reports on experimentally determined POST topology. We experimentally tested the consensus prediction across multiple in silico transmembrane domain prediction programs that POST had 10 transmembrane domains (Fig. 4A). A fluorescence protease protection (FPP) assay in HEK 293T cells transiently transfected with N-terminally or C-terminally tagged POST revealed the consensus prediction was not correct. This assay is based on the ability of trypsin to degrade fluorescent proteins when localized within the same compartment. Trypsin addition to the outside of cells failed to significantly affect fluorescence in the presence of STIM1-YFP, mCherry-POST, or POST-GFP (Fig. 4, B to F), indicating that POST, like STIM1, is predominantly found within the ER. The addition of digitonin, which permeabilizes the PM, but not the ER membrane, led to loss of fluorescence of STIM1-YFP (Fig. 4, B, C, and F) and mCherry-POST (Fig. 4, B, D, and F), but not POST-GFP, indicating that the N-terminus of POST is in the cytosol. POST-GFP fluorescence could not be quenched in the presence of digitonin but was quenched when all membranes were permeabilized upon the addition of Triton X-100 (Fig. 4, B, E, and F). These findings indicate that the POST C-terminus is found within the ER lumen whereas the N-terminus is localized to the cytosol. Because a 7 transmembrane domains topology was not predicted by any software program and 11 transmembrane domains is unlikely for a protein of this size, POST most likely has 9 transmembrane domains.

Figure 4: POST has 9 transmembrane domains.

(A) Summary of the predicted number of POST transmembrane domains amongst in silico protein topology prediction programs. The consensus prediction is 10 transmembrane domains. (B to F) The intracellular localization of the N- and C-termini of POST in HEK293 cells was determined by fluorescence protease protection (FPP) assays following trypsin (Trp), digitonin (Dig), and Triton X-100 (Tx). Representative images are shown of fluorescence quenching by trypsin digestion with detergent addition (B; scale bar=5 μm), and representative traces of FPP assays in HEK293 cells expressing C-terminally tagged STIM1 (C), mCherry-POST (D), or POST-GFP (E). Stacked average relative fractions ±SEM of N-terminally (mCherry-POST) and C-terminally (POST-GFP) tagged POST (F). Data are from 3 independent experiments; 17 to 38 cells.

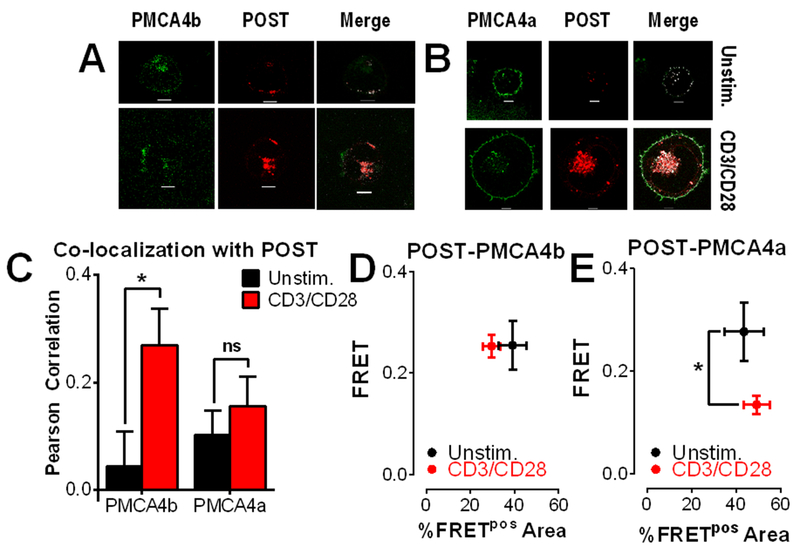

POST and PMCA4 interactions are activation-dependent

Splice variant-dependent interactions between POST and PMCA4 were then examined based on our findings on POST topology (Fig. 5). Jurkat T cells were transfected with mCherry-POST and either GFP-PMCA4b (Fig. 5A) or GFP-PMCA4a (Fig. 5B) and activated for 2 hours on anti-CD3/CD28-coated coverslips. Upon activation, both PMCA4a and PMCA4b translocated to the bottom of the cell (Fig. 5, A and B), although significant increases in association with POST were observed for PMCA4b only (Fig. 5C). We then examined association between POST and PMCA4 by measuring FRET by acceptor photobleaching (Fig. 5, D and E). POST and PMCA4b exhibited robust and stable FRET that was unaffected by T cell activation; since there was an ~3-fold increase in colocalization between POST and PMCA4b, this would reflect a substantial overall increase in association between these 2 proteins. In contrast, FRET between POST and PMCA4a significantly decreased upon T cell activation (Fig. 5E). Considered collectively, these observations reveal a much stronger affinity for PMCA4b by POST, consistent with our observations that PMCA4b-mediated Ca2+ clearance is more sensitive regulation by POST (Fig. 2).

Figure 5: Activation-dependent interactions between POST and PMCA4.

(A and B) Representative images of Jurkat T cells co-transfected with mCherry-POST (red) and either GFP-PMCA4b (green; A) or GFP-PMCA4a (green; B). Colocalization is shown in white. Scale bar=5 μm. (C) Co-localization between POST and PMCA4a or PMCA4b in cells represented in (A) was calculated by Pearson correlation, presented as the average ± SEM of 20-27 cells (>5 independent experiments). Two-way ANOVA; *P<0.05 (ns, not significant). (D and E) FRET by acceptor photobleaching between POST and PMCA4b (D) or PMCA4a (E) was analyzed as above in Fig. 1I; *p<0.05.

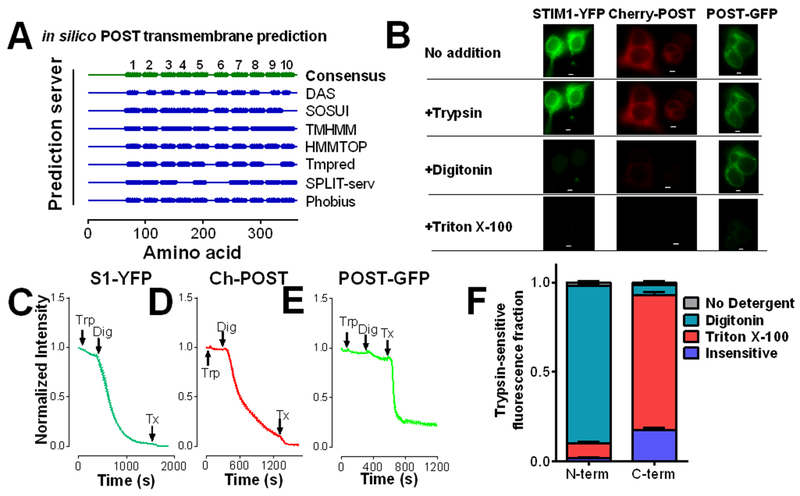

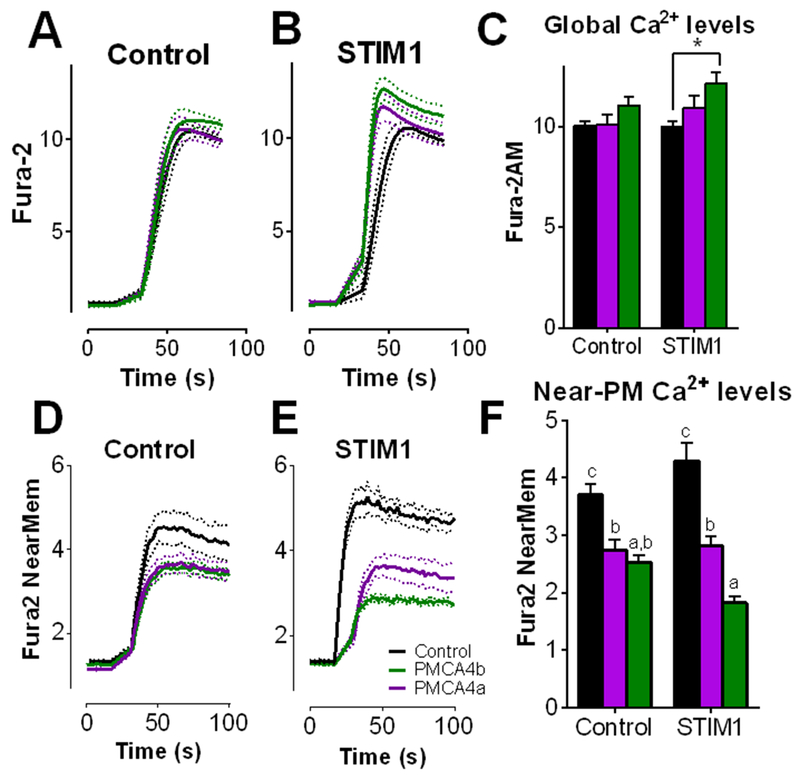

PMCA4b expression lowers near-membrane, but not global, cytosolic Ca2+ abundance

The observations described above provide insight into the roles of POST and STIM1 as regulators of PMCA4 activity, but how PMCA4 activity leads to increased NFAT-mediated transcription (Fig. 1) is unclear. Given the dependence of NFAT activity upon Ca2+ microdomains (23) and the vulnerability of Orai1 activation to Ca2+, prolonged NFAT activation must require a delicate balance between local Ca2+ increases and Ca2+-dependent inhibition (23, 25, 31). The extent to which PMCA activity contributes to this balance has not previously been addressed. Notably, since electrophysiological approaches require strong Ca2+ chelation to avoid Ca2+-dependent inhibition, these questions can only be addressed through Ca2+ imaging. For these studies, Jurkat T cells were loaded with either Fura-2 AM to measure global cytosolic Ca2+ content or a lipid-conjugated form of Fura-2 AM termed Fura-2 NearMem (NM) (Teflabs Inc) that is limited to and only measures the Ca2+ concentration near membranes. Examination of its localization shows clear sequestration relative to Fura-2 (fig. S5). Although substantial staining of both the ER and PM is visible, treatment with thapsigargin before the measurement of Ca2+ entry and clearance precludes interference from ER Ca2+ cycling. Hence, under these conditions, Fura2NM measurements primarily reflect Ca2+ flux across the PM.

Overexpression of either PMCA4a or PMCA4b had minimal effect on global SOCE (Fig. 6, A to C). In contrast, PMCA4 overexpression led to substantially lower NearMem Ca2+ concentration during SOCE under all conditions (Fig 6, D to F). This effect was greatly enhanced by co-expression of STIM1 and PMCA4b; coexpression of STIM1 and PMCA4b markedly decreased Ca2+ near the PM, yet global Ca2+ was modestly but significantly enhanced. This is consistent with the condition in which maximal NFAT activation was observed (Fig. 1A). Therefore, regulation of PMCA4 can shape Ca2+ dynamics at the PM that are inversely correlated with global Ca2+ dynamics. Additionally, STIM1 co-expressed with PMCA4a had no effect on global Ca2+ concentration, revealing splice variant dependence for control of Ca2+ entry (Fig. 6, B and C).

Figure 6: PMCA4b expression lowers near-membrane, but not global cytosolic Ca2+ levels.

Jurkat T cells were transfected with empty vector (control) or mCherry-STIM1 (STIM1) along with empty vector (black), GFP-PMCA4a (purple), or GFP-PMCA4b (green) and incubated for 24 hours before serum starving (3 hours) and plating on CD3/CD28 antibodies. Cells were loaded with Fura-2 AM to measure global cytosolic Ca2+ levels (A to C) or the near-PM Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 NearMem (D to F). ER Ca2+ was depleted with thapsigargin in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ prior to time 0; Ca2+ entry was measured upon the addition of 1 mM Ca2+. Traces shown are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments, each consisting of 40 to 60 cells. Entry was calculated as the maximum F340/F380 - minimum F340/F380 of each cell. *P<0.05 by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. In (F), statistically significant differences amongst each condition is indicated by a, b, c; p<0.05.

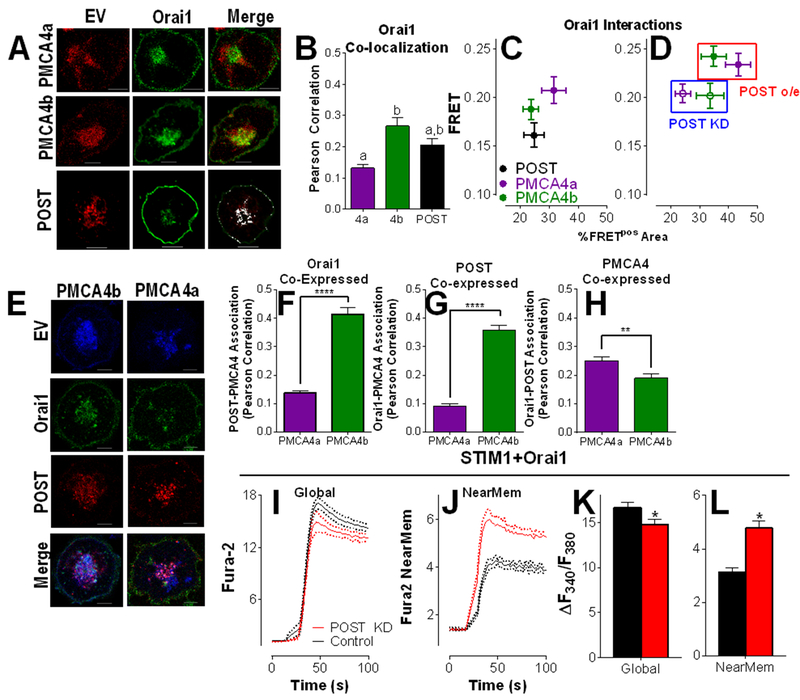

This inverse relationship between near-PM and global cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations lends powerful support to the concept of near-PM Ca2+ clearance contributing to efficient Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry and NFAT activation. Since POST positively regulated PMCA4-mediated Ca2+ clearance (Figs. 2 and 3), we assessed its potential role coupling Ca2+ clearance to Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry. Significant colocalization between Orai1 and POST, PMCA4a or PMCA4b was observed, with preferential localization with PMCA4b (Fig. 7, A and B). To determine if association between Orai1 and either POST or PMCA4 reflects direct interaction, FRET analysis of Orai1 and its potential interacting partners was performed (Fig. 7C). Although substantial FRET was observed in all cases, the closest interaction was observed between PMCA4a and Orai1, whereas POST-Orai1 interactions were the weakest. To determine the contribution of POST to PMCA4-Orai1 interaction, FRET was measured between Orai1-PMCA4 with POST coexpression or knockdown (Fig 7D). POST co-expression increased both efficiency and area of PMCA4-Orai1 FRET, whereas POST knockdown had the reverse effect. Further, POST co-expression increased co-localization between PMCA4b and Orai1 (Fig. 7, E and F; compare with Fig. 7B) and the presence of Orai1 increased PMCA4b association with POST (Fig. 7, E and G; compare with Fig. 5C). A corresponding decrease in PMCA4a association with each of POST and Orai1 was observed (Fig. 7, E to G). Finally, a modest, but statistically significant increase in Orai1-POST association was observed in PMCA4b-expressing over PMCA4a-expressing cells (Fig. 7, E and H). Considered collectively, these observations reveal significant and interdependent interactions in which POST regulates preferential Orai1-PMCA4b interactions during T cell activation.

Figure 7: POST couples PMCA4-mediated Ca2+ clearance to Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry.

(A) Representative images of Jurkat T cells co-transfected with CFP-Orai1, mCherry-POST, and either GFP-PMCA4b or GFP-PMCA4a, and serum starved before plating on anti-CD3/CD28 coated coverslips. Scale bar= 5 μM. (B) Co-localization between Orai1 and either PMCA4a, PMCA4b or POST was measured by Pearson correlation in cells described in (A); means ± SEM are plotted; n=12-21 cells per condition. Unpaired two-tailed T-tests determined statistical significance; ****P<0.0001. (C) FRET by acceptor photobleaching was performed in cells expressing Orai1 and each of POST, PMCA4b and PMCA4a and analyzed as previously described (Fig. 1I) (D) FRET experiments between Orai1 and PMCA4 described in panel C were repeated after co-expression with POST siRNA (POST KD) or mCherry-POST (POST o/e, average ± SEM are plotted. Data in panels C and D are average ± SEM, n=15-20 cells per condition. (E to H) Representative images (E) of activated Jurkat T cells co-transfected with Orai1-YFP (green) and mCherry-POST (red) along with either CFP-PMCA4a or CFP-PMCA4b (blue). Colocalization between POST and PMCA4 (F), Orai1 and PMCA4 (G), and Orai1 and POST (H) was quantified by Pearson correlation; n=29-31 cells per condition. Unpaired two-tailed T-tests determined statistical significance; ** P<0.01; **** P<0.0001. (I to L) Jurkat T cells were transfected with YFP-STIM1, CFP-Orai1 and either scrambled RNA or POST siRNA before a 24-hour incubation and serum starvation (3 hours). Cells were plated on CD3/CD28 antibodies and loaded with either Fura-2 AM to measure global cytosolic Ca2+ levels (I) or the near-PM Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 NearMem (J). Traces shown are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments, each consisting of 40 to 60 cells. (K and L) Ca2+ entry for each condition was analyzed by 2-way ANOVA; the difference between global and near-MEM Ca2+ entry was p<0.0001; the effect of POST was p>0.05; interdependence between POST expression and changes in Ca2+ entry was p=0.017. * indicates statistical differences due to POST overexpression (p < 0.05).

Finally, to determine the functional implications of endogenous POST on these interactions, NearMem and global Ca2+ concentrations were measured during Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry. In STIM1/Orai1-overexpressing cells, POST knockdown decreased global Ca2+ concentrations and increased near-PM Ca2+ concentrations (Fig 7, I to L), consistent with the concept that POST couples PMCA4-mediated Ca2+ clearance to Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry.

Discussion

These investigations considerably expand our understanding of the role of POST-mediated regulation of Ca2+ dynamics in a physiological process. Consistent with prior studies (17), we observed a statistically significant increase in the rate of Ca2+ clearance in unstimulated ER Ca2+ store-depleted cells, although these differences were relatively small compared to the acceleration of Ca2+ clearance that occurs upon POST overexpression. Considering the newly defined ability of POST to interfere with STIM1-mediated PMCA4 inhibition and activation-induced dissociation from PMCA4a, current thinking regarding POST-mediated control of Ca2+ clearance requires revision.

We were intrigued and surprised to find that PMCA4b and STIM1 overexpression would lead to more efficient clearing of near-membrane Ca2+ during Ca2+ entry, in contrast with previous studies showing that STIM1 inhibits PMCA4 function in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (15, 16). There are several factors that must be considered to address this paradox. The first is that POST associates with STIM1 and PMCA4, likely protecting against STIM1-mediated inhibition. Since POST also associates with Orai1, the physiological role of POST may be to recruit PMCA4 to the active STIM-Orai complex, thereby facilitating Ca2+ disinhibition. A second consideration is that STIM1-mediated inhibition is limited to the slow phase of Ca2+ clearance, the kinetics of which may have little bearing in the context of countering local Ca2+ entry next to the open Orai1 pore. Hence, inhibition of PMCA4 by STIM1 may be more relevant during the shutdown phase of a Ca2+ signal, perhaps facilitating an extended Ca2+ response after Orai1 inactivation.

The ability of a Ca2+ pump to modulate the function of a Ca2+ channel may itself be surprising, considering the rate of diffusion vs. Ca2+ pumping against a diffusion gradient. It is important to note that STIM and Orai are found in ER-PM junctions where the free diffusion of Ca2+ may be limited by physical barriers. Further, estimates of the rate of Ca2+ entry through a channel are based upon measurements made in the presence of strong Ca2+ chelators. Without chelation or Ca2+ clearance through the action of PMCA and/or SERCA, the concentration of Ca2+ would rapidly increase within the confined space of the ER-PM junction, decreasing the driving force as well as forcing Ca2+-dependent inhibition. Furthermore, past literature has demonstrated in intact Jurkat T cells that when Ca2+ is not removed following induction of SOCE that the amount of Ca2+ reaches a plateau as clearance through PMCA attains equilibrium with Ca2+ influx (30). Thus, in the context of physiologic Ca2+ signaling, the question of how Ca2+ transporters shape Ca2+ transients driven by channels is a compelling area of inquiry.

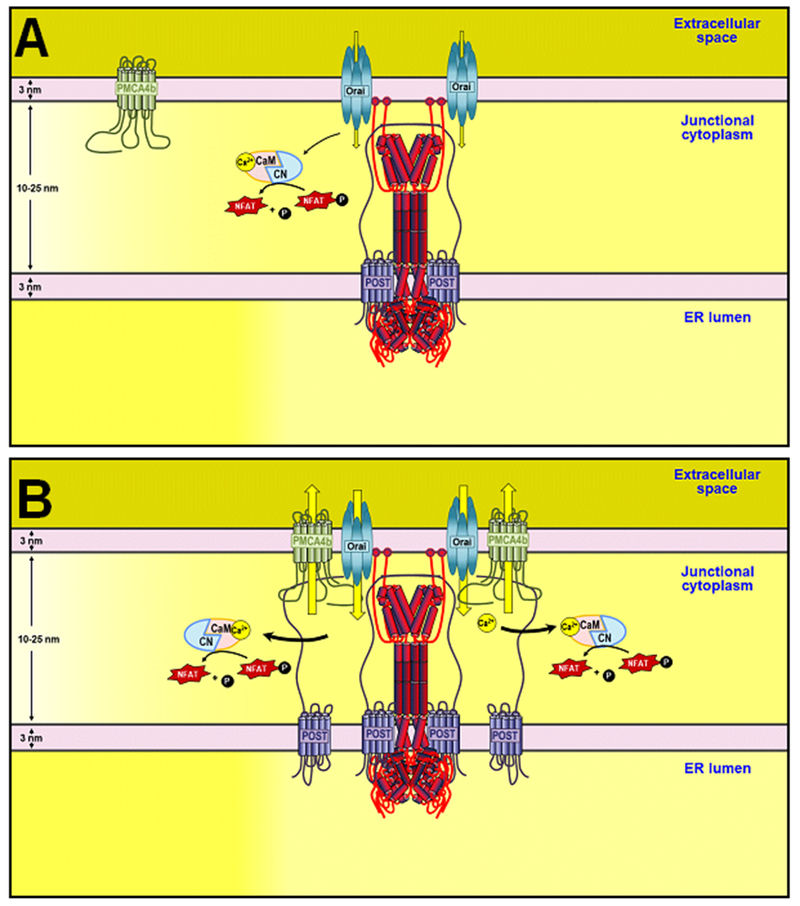

The paradoxical finding that increased expression of Ca2+ extruding protein PMCA4 enhances NFAT activation was the observation that ultimately guided this study. The data presented here reveals a role for POST in Ca2+ disinhibition through coupling of PMCA4 and Orai1. It seems somewhat counter-intuitive that Ca2+ would be permitted to enter the cell only to be pumped right out again, however, if NFAT activation is tightly coupled to Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry as previously theorized (32) and supported by the current study, then the rapid removal of Ca2+ from the vicinity of Orai1 would be predicted to maximally facilitate NFAT activation (Fig. 8, A and B). If so, this mechanism would be predicted to increase T cell activation. Further, considering the widespread expression of NFAT and the Ca2+ signaling proteins involved in this mechanism, these findings may also have implications for the regulation of NFAT-targeted gene expression programs in a myriad of cellular processes.

Figure 8: Ca2+ entry/clearance coupling increases NFAT activation.

Model of the results and proposed mechanism. During T cell activation, InsP3-induced store depletion leads to the activation of STIM1 and Ca2+ influx through Orai1. Without recruitment and regulation of PMCA4b function by STIM1 and POST (A), Orai1 channels allow Ca2+ influx, followed by Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the channel. NFAT activation is limited by the large but transient activation of Orai1. Recruitment of POST and PMCA4b to the IS with STIM1 and Orai1 (B) leads to extrusion of Ca2+ in the immediate vicinity of Orai1. This prevents Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Orai1 facilitating greater NFAT activation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Human anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 were obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Poly-L-lysine was produced by Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). Fura-2 AM was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Thapsigargin was obtained from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Trypsin, digitonin, and Triton X-100 for the FPP assays were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. EGTA was obtained from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Plasmids

GFP-PMCA4b was a generous gift from Emanuel Strehler (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). PMCA4a was cloned from a pMM2-hPMCA4a plasmid also generously provided by Emanuel Strehler, and GFP-PMCA4a generated by Mutagenex (Suwanee, GA). POST-GFP was generously provided by David Clapham (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, VA); all other POST constructs were generated by Mutagenex (Suwanee, GA). The STIM1-YFP was obtained from Anjana Rao (La Jolla Institute, San Diego, CA). NFAT-IFN-luciferase was a generous gift from Joel Pomerantz (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). mCherry-STIM1 was from Richard Lewis (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). Scrambled control RNA was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. HA-STIM1-mCherry was generated by Mutagenex (Suwanee, GA). POST knockdown by RNAi was accomplished with an siRNA generated by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA): sense 5’-GGACUACUUUCUGAGCAUUUGGUAU-3’, antisense 5’-AUACCAAAUGCUCA GAAAGUAGUCC-3’.

Cell culture

Jurkat T cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 + L-glutamine (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. HEK 293 cells were cultured in DMEM + 4.5 g/L glucose, L-glutamine, & sodium pyruvate (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cell transfection

Jurkat T cells or HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected by electroporation on the Biorad GenePulser Xcell and cultured in Opti-MEM (Gibco) for 3 hours before supplementation with 10% FBS. For cells co-transfected with STIM1 and Orai1 constructs 600 μM EGTA was also added to avoid Ca2+ overload.

Fluorescence protease protection assay

The fluorescence protease protection assay was adapted from the protocol developed by (33). HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected for 24 hours with N- (mCherry-POST) or C-terminally tagged (POST-GFP) constructs by electroporation. KHM buffer (110 mM KOAc, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM MgCl2) was supplemented with 30 μM trypsin, 50 μM digitonin, and 1% Triton X-100 as described in the results section. Trypsin-free, trypsin + digitonin, and trypsin + Triton X-100-containing KHM buffers were successively added and fluorescence measured to determine quenching. Experiments were performed on a Leica DMI 6000B fluorescence microscope controlled by Slidebook Software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations; Denver, CO).

FRET by acceptor photobleaching

Jurkat T cells were transiently transfected with GFP and mCherry-tagged construct pairs expressing STIM1, POST, PMCA4a or PMCA4b. Experiments were performed on a Leica SP8 laser scanning microscope equipped with 405, 488, 552, and 638 nm solid state lasers. The FRET acceptor (mCherry) was bleached at 100% laser power for 15 iterations in regions of the cell where there was visible colocalization with GFP. The change in donor (GFP) fluorescence was measured using PMT detector channels. FRET efficiency was calculated as:

FRET values <0.1 were excluded. The percentage of FRET positive area (%FRETpos Area) was calculated as the area of regions in which FRET was detected (μm2) divided by the total area photobleached (μm2) multiplied by 100.

NFAT luciferase assay

Jurkat T cells were transiently transfected with 8 μg NFAT-IFN-luciferase and 2 μg Renilla by electroporation (Lonza) for 48 hours before serum starvation for 3 hours. Cells were then incubated with 3 μM anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 6 hrs. Luciferase was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) in white flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a GloMax Multi Detection reader (Promega) with an integration time of 0.5 seconds. Luciferase counts were normalized to Renilla counts. Averages are presented ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments and analyzed by two-way ANOVA to determine statistical significance.

Quantitative PCR

qPCR was performed as previously described (16). RNA was extracted using RNA Bee (Tel-Test) followed by addition of 0.2 mL chloroform per 1 mL RNA Bee and phase separation by centrifugation. RNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol, spun down, and washed with 75% ethanol. Libraries of cDNA were generated using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and quantitative PCR performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a 7300 Real-Time PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data are presented as the target expression level normalized to control protein expression level (TATA-box binding protein, TBP) with the following primers: Human POST sense (5’-TGCCTTTCCTCGCCGTGTTG-3’), antisense (5’-TTCTTCTTGGCTTCCGGCTC-3’); human PMCA4a (ATP2B4a) sense (5’-CATGGGTCAACACC TTGATG-3’), antisense (5’-TGGTGCAACTGCTACATAGG-3’); human PMCA4b (ATP2B4b) sense (5’-ACTCAGATCAAGTGGTCA-3’), antisense (5’-GTTTCTGAATGCTTTCGTGG-3’); human TBP sense (5′-CAGCC GTTCAGCAGTCAA-3′), antisense (5′-GGAGGGATACAGT GGAGT-3′). To design PMCA4 splice variant-specific primers, Primer-BLAST was used to design primers targeting exon 20 to specifically amplify PMCA4a; to specifically amplify PMCA4b, which skips exon 20, primers were designed to span the splice site between exons 19 and 21 (34). The specificity of each primer pair was analyzed by DNA PAGE. Reactions from qPCR were run on a 12% gel followed by ethidium bromide staining. Predicted amplicon size for PMCA4a primers is 61 base pairs; predicted amplicon size for PMCA4b is 58 base pairs (fig. S6).

Ca2+ measurements

Cytosolic Ca2+ measurements were performed as previously described (15). Cells were serum starved in RPMI 1640 + L-glutamine supplemented with 0.5% BSA for 3 hours and plated on coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine or anti-CD3/CD28. Cells were loaded with 2 μM Fura-2 acetoxymethylester (Invitrogen) or 2 μM Fura-2NM acetoxymethylester (Teflabs) for 30 minutes at 25°C in cation-safe solution (107 mM NaCl, 7.2 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 11.5 mM glucose, 20 mM Hepes-NaOH, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2). Cells were washed and dye allowed to de-esterify for 30 minutes at 25°C. Ca2+ measurements were made using a Leica DMI 6000B fluorescence microscope controlled by Slidebook Software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations; Denver, CO). Intracellular Ca2+ measurements are shown as 340/380 nm ratios obtained from groups of single cells. To measure PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance, cells were store depleted in 2 μM thapsigargin. Following store depletion, SOCE was induced by the addition of 1 mM Ca2+ and measured for 2 minutes, followed by Ca2+ clearance for 10 minutes in Ca2+-free imaging buffer + 100 nM EGTA.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by One-Way or Two-Way ANOVA where appropriate using Graph Pad Prism, as specified within the figure legends. Within each figure, statistical groups are conveyed by small letters, with statistical differences (p < 0.05) determined by Tukey’s post-hoc tests. Hence, group ‘a’ is different from ‘b’ is different from ‘c’. In some cases, specific experimental conditions were not significantly different from multiple groups. In this scenario, the condition was labelled with multiple letters.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Representative Ca2+ traces associated with Ca2+ clearance data.

Fig. S2: Representative Ca2+ traces associated with Ca2+ clearance data from Figure 2.

Fig. S3: Validation of POST knockdown by siRNA.

Fig. S4: Representative Ca2+ traces associated with Ca2+ clearance data from Figure 3C–F.

Fig. S5: Representative images of Jurkat T cells containing Fura-2 or Fura-2NM.

Fig. S6: Validation of qPCR primer design for ATP2B4 splice variants.

Table S1: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 1, I and J.

Table S2: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 2, E to G (unstimulated cells).

Table S3: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 2, I to J (CD3/CD28 antibody-treated cells).

Table S4: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 3, C and D.

Table S5: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 3, E and F.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. Emanuel Strehler (Mayo Clinic) for the pMM2-hPMCA4a plasmid, Dr. David Clapham (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, VA) for POST-GFP, Dr. Anjana Rao (La Jolla Institute, San Diego, CA) for STIM1-YFP, Dr. Joel Pomerantz (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) for the NFAT-IFN-luciferase vector and Dr. Richard Lewis (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) for the mCherry-STIM1 construct.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R01GM097335 (JS) and R01GM117907 (JS).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes:

- 1.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD, The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 1, 11 (October, 2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soboloff J, Rothberg BS, Madesh M, Gill DL, STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 549 (September, 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Rao A, Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annual review of immunology 28, 491 (March, 2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feske S, ORAI1 and STIM1 deficiency in human and mice: roles of store-operated Ca2+ entry in the immune system and beyond. Immunological reviews 231, 189 (September, 2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhuri K et al. , Polarized release of T-cell-receptor-enriched microvesicles at the immunological synapse. Nature 507, 118 (March 06, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang GN et al. , STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, I(crac) and TRPC1 channels. Nat Cell Biol 8, 1003 (September, 2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Huang GN, Worley PF, Muallem S, STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nat Cell Biol 9, 636 (June, 2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng W et al. , STIM1 gates TRPC channels, but not Orai1, by electrostatic interaction. Mol Cell 32, 439 (November 7, 2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bird GS, DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Putney JW Jr., Methods for studying store-operated calcium entry. Methods 46, 204 (November, 2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefkimmiatis K et al. , Store-operated cyclic AMP signalling mediated by STIM1. Nat Cell Biol 11, 433 (April, 2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motiani RK et al. , STIM1 activation of adenylyl cyclase 6 connects Ca(2+) and cAMP signaling during melanogenesis. EMBO J, (January 8, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willoughby D et al. , Direct binding between Orai1 and AC8 mediates dynamic interplay between Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Sci Signal 5, ra29 (April 10, 2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y et al. , The calcium store sensor, STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science 330, 105 (October 01, 2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park CY, Shcheglovitov A, Dolmetsch R, The CRAC channel activator STIM1 binds and inhibits L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. Science 330, 101 (October 1, 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie MF, Samakai E, Soboloff J, STIM1 is required for attenuation of PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance during T-cell activation. EMBO J 31, 1123 (March 07, 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samakai E et al. , Novel STIM1-dependent control of Ca2+ clearance regulates NFAT activity during T-cell activation. FASEB J 30, 3878 (November, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Stotz SC, Manasian Y, Clapham DE, POST, partner of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), targets STIM1 to multiple transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 19234 (November 29, 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noh DY, Shin SH, Rhee SG, Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C and mitogenic signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1242, 99 (December 18, 1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bautista DM, Lewis RS, Modulation of plasma membrane calcium-ATPase activity by local calcium microdomains near CRAC channels in human T cells. J Physiol 556, 805 (May 1, 2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parekh AB, Ca2+ microdomains near plasma membrane Ca2+ channels: impact on cell function. J Physiol 586, 3043 (July 1, 2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gwack Y et al. , Hair loss and defective T- and B-cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol Cell Biol 28, 5209 (September, 2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh-Hora M et al. , Agonist-selected T cell development requires strong T cell receptor signaling and store-operated calcium entry. Immunity 38, 881 (May 23, 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kar P, Nelson C, Parekh AB, Selective activation of the transcription factor NFAT1 by calcium microdomains near Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. J Biol Chem 286, 14795 (April 29, 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng SW et al. , Cysteinyl leukotriene type I receptor desensitization sustains Ca2+-dependent gene expression. Nature 482, 111 (February 2, 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoth M, Penner R, Calcium release-activated calcium current in rat mast cells. J Physiol 465, 359 (June, 1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zweifach A, Lewis RS, Rapid inactivation of depletion-activated calcium current (ICRAC) due to local calcium feedback. J Gen Physiol 105, 209 (February, 1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quintana A et al. , Calcium microdomains at the immunological synapse: how ORAI channels, mitochondria and calcium pumps generate local calcium signals for efficient T-cell activation. EMBO J 30, 3895 (August 16, 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunnell SC, Kapoor V, Trible RP, Zhang W, Samelson LE, Dynamic actin polymerization drives T cell receptor-induced spreading: a role for the signal transduction adaptor LAT. Immunity 14, 315 (March, 2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS, T cell activation. Annual review of immunology 27, 591 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bautista DM, Hoth M, Lewis RS, Enhancement of calcium signalling dynamics and stability by delayed modulation of the plasma-membrane calcium-ATPase in human T cells. J Physiol 541, 877 (June 15, 2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullins FM, Park CY, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, STIM1 and calmodulin interact with Orai1 to induce Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CRAC channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 15495 (September 8, 2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang WC et al. , Local Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels stimulates production of an intracellular messenger and an intercellular pro-inflammatory signal. J Biol Chem 283, 4622 (February 22, 2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorenz H, Hailey DW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Fluorescence protease protection of GFP chimeras to reveal protein topology and subcellular localization. Nat Methods 3, 205 (March, 2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strehler EE, Plasma membrane calcium ATPases: From generic Ca(2+) sump pumps to versatile systems for fine-tuning cellular Ca(2.). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 460, 26 (April 24, 2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Representative Ca2+ traces associated with Ca2+ clearance data.

Fig. S2: Representative Ca2+ traces associated with Ca2+ clearance data from Figure 2.

Fig. S3: Validation of POST knockdown by siRNA.

Fig. S4: Representative Ca2+ traces associated with Ca2+ clearance data from Figure 3C–F.

Fig. S5: Representative images of Jurkat T cells containing Fura-2 or Fura-2NM.

Fig. S6: Validation of qPCR primer design for ATP2B4 splice variants.

Table S1: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 1, I and J.

Table S2: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 2, E to G (unstimulated cells).

Table S3: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 2, I to J (CD3/CD28 antibody-treated cells).

Table S4: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 3, C and D.

Table S5: Calculated non-linear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays from Figure 3, E and F.