Abstract

Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) prevalence in priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly among men aged ≥20 years, has not yet reached the goal of 80% coverage recommended by the World Health Organization. Determining novel strategies to increase VMMC uptake among men ≥20 years is critical to reach HIV epidemic control. We conducted a systematic review to analyze the effectiveness of economic compensation and incentives to increase VMMC uptake among older men in order to inform VMMC demand creation programs. The review included five qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies published in peer reviewed journals. Data was extracted into a study summary table, and tables synthesizing study characteristics and results. Results indicate that cash reimbursements for transportation and food vouchers of small nominal amounts to partially compensate for wage loss were effective, while enrollment into lotteries offering prizes were not. Economic compensation provided a final push toward VMMC uptake for men who had already been considering undergoing circumcision. This was in settings with high circumcision prevalence brought by various VMMC demand creation strategies. Lottery prizes offered in the studies did not appear to help overcome barriers to access VMMC and qualitative evidence suggests this may partially explain why they were not effective. Economic compensation may help to increase VMMC uptake in priority countries with high circumcision prevalence when it addresses barriers to uptake. Ethical considerations, sustainability, and possible externalities should be carefully analyzed in countries considering economic compensation as an additional strategy to increase VMMC uptake.

Keywords: Voluntary medical male circumcision, HIV prevention, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Three randomized controlled trials conducted in Kenya, South Africa and Uganda provided evidence that voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) reduces the risk of HIV transmission from women to men by approximately 60% (Auvert et al., 2005; Bailey et al., 2007; Gray et al., 2007). In 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Joint United Nations Programe on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) recommended that VMMC be scaled up in settings with high HIV and low male circumcision prevalence (WHO/UNAIDS, 2007). Initial recommendations suggested that VMMC programs should target HIV-negative males aged 15–49 years as part of a public health approach (WHO/ UNAIDS, 2007). From 2008 to 2015, approximately 11.7 million males aged ≥10 years were circumcised in 14 VMMC priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa (WHO, 2016), representing 56% of the initial target of 20.8 million VMMCs by 2016 (WHO, 2015). Given resource limitations and that VMMC was not a social norm in several priority countries, reaching 56% of the initial target is a substantial accomplishment.

While VMMC scale-up has been impressive, services have mostly appealed to clients aged ≤20 years, and particularly males aged 10–14 years. For example, in Iringa, Tanzania, 75.7% of VMMC clients from five health facilities during a VMMC campaign in 2010 were aged ≤19 years (Mahler et al., 2011), in Kenya 29% of clients seeking VMMC services from 81 government health facilities were aged ≤15 years (Herman-Roloff, Llewellyn, et al., 2011), and in Malawi, 33.8% of clients were aged 16–18 years (Carrasco, Nguyen, & Kaufman, 2016). Mathematical modeling suggested that most VMMC programs could maximize the immediacy of impact on HIV incidence by targeting men aged 20–34 years (Kripke, Okello, et al., 2016; Kripke, Opuni, et al., 2016) instead of younger boys at lower HIV. Most countries in eastern and southern Africa have refined their VMMC demand creation targets to prioritize 15–29 year olds, while some also target adolescents (10–14 years) and adults aged 30–34 years.

In order to reach VMMC targets and achieve HIV epidemic control in the short- and mid-term, it is critical to identify evidence-based interventions to improve VMMC uptake among men aged ≥20 years. Since VMMC scale-up began, various strategies to increase uptake have been implemented across priority countries including: mass media campaigns, local community mobilization campaigns with religious leaders and other influential champions, radio programs, and dissemination of written materials about VMMC specifically focused on women to engage them in motivating male partners (Health Communication Capacity Collaborative, 2016). These strategies were designed to convey information about VMMC, capitalize on factors promoting VMMC uptake, and address barriers identified through formative research. For adult men, such barriers include the perception of VMMC being exclusively for youth (Herman-Roloff, Otieno, Agot, Ndinya-Achola, & Bailey, 2011; Macintyre et al., 2014); a practice introduced by foreign cultures and religions (Chikutsa, Ncube, & Mutsau, 2015; Montaño, Kasprzyk, Hamilton, Tshimanga, & Gorn, 2014; Rennie, Perry, Corneli, Chilungo, & Umar, 2015); pain or fear of surgery (Evens et al., 2014; A. Herman-Roloff, Llewellyn, et al., 2011; Westercamp, Agot, Ndinya-Achola, & Bailey, 2012); and lost wages due to missed work from VMMC surgery and recovery (Evens et al., 2014; Plotkin et al., 2013; Ssekubugu et al., 2013; Westercamp et al., 2012). The provision of economic compensation and incentives to potential VMMC clients has not been widely implemented in part due to the lack of consensus around effectiveness and the specific contexts where they may be most appropriate. The purpose of this review is to summarize the characteristics and synthesize the findings of VMMC demand creation interventions that have provided economic compensation and incentives to potential clients to facilitate or promote VMMC uptake.

Economic compensation and incentives

We defined “economic compensation” as any monetary or in-kind payments made to potential clients to encourage or facilitate access to VMMC. Such payments may reduce a perceived barrier to accessing VMMC services (i.e., providing cash with the intent to cover for transportation costs, providing food vouchers to help defray food costs in the event of lost wages). “Incentives” are defined as potential payments (i.e., the receipt of payment is not guaranteed), such as lotteries or raffles, that may motivate potential clients to access VMMC. A common characteristic to the economic compensation and incentives that were analyzed in this review is that receiving the economic compensation or incentive is conditional on accessing VMMC services, either to receive information about VMMC and/or to undergo circumcision.

The use of such conditionalities to promote uptake of health behaviors or services is not new. Conditional cash transfers (CCTs), for example, have used to provide assistance to at-risk individuals or households by providing monetary payments for adhering to behavioral goals or achieving predetermined health outcomes (Krubiner, 2015). The effectiveness of CCTs has been tested in studies of HIV prevention (Pettifor, MacPhail, Nguyen, & Rosenberg, 2012), child health (Fernald, Gertler, & Neufeld, 2008), maternal health (Lim et al., 2010), and tuberculosis control (Boccia et al., 2011). In lieu of cash, other in-kind transfers such as food vouchers or lotteries have also been used in health programs (USAID, 2010).

Various studies have documented a positive impact of CCTs on health (Gaarder, Glassman, & Todd, 2010; Lagarde, Haines, & Palmer, 2007). CCTs, however, have not always been effective in achieving specific health outcomes like HIV prevention (Kohler & Thornton, 2012), and the evidence of CCTs promoting positive health behaviors and outcomes is mixed in the sub-Saharan African context (USAID, 2010). For example, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Malawi found that cash transfers increased school attendance and reduced HIV and HSV-2 incidence (Baird, Garfein, McIntosh, & Özler, 2012), while a RCT in South Africa found that cash transfers did not increase school attendance or reduce HIV or HSV-2 incidence (Pettifor et al., 2016). In addition to the limited evidence, other important challenges to using incentives in health programing include ethical considerations related to unduly influencing clients, sustainability considerations, undermining patients’ responsibility for their own health, and perceptions of donor paternalism (USAID, 2010).

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We followed the PRISMA protocol to conduct our systematic review (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009). We performed a search of the peer-reviewed literature using PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and PsycINFO databases. We searched these databases using the keywords “voluntary medical male circumcision” AND (“incentive” OR “payment”) in any field of the database. For the manual search, we reviewed references of relevant peer-reviewed articles and consulted with VMMC experts.

To be included in this review, the studies had to meet the following criteria:

-

(1)

Published in a peer-reviewed journal;

-

(2)

Analyzed data from impact evaluations on the effect of incentives provided to potential clients of VMMC services;

-

(3)

Included data from one or more of the 14 VMMC priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa;

-

(4)

Written in English.

Study selection

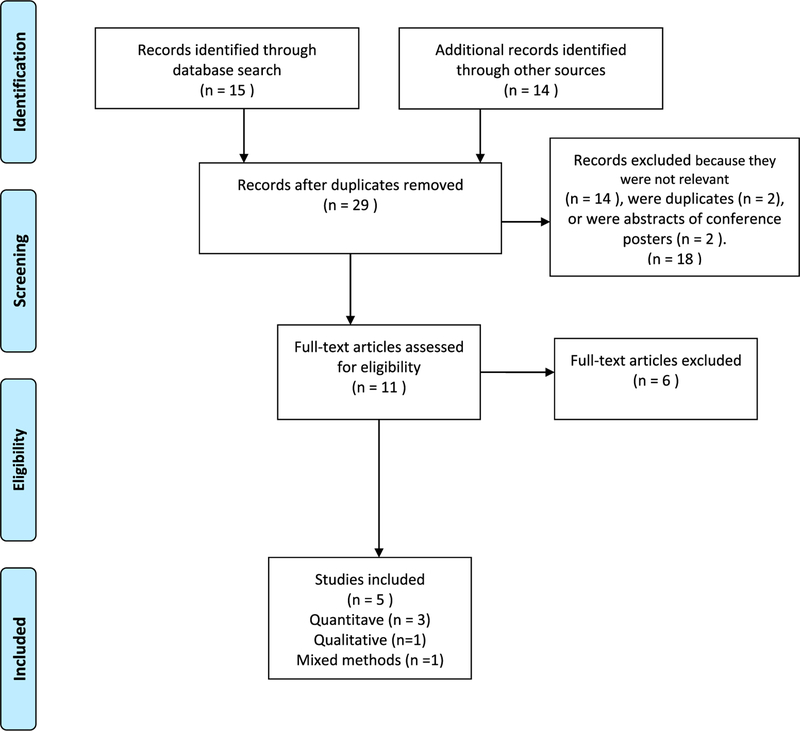

The original database search was performed on August 2016 and yielded 15 manuscripts. Four manuscripts were added through searching reference lists. Additionally, experts recommended 10 impact evaluations of potentially relevant VMMC demand creation interventions, which were added to our original list for a total of 14 articles found manually and from expert consultation. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA flowchart of the selection process for the studies included. Eighteen articles were excluded as duplicates or because they did not meet the inclusion criteria based on title and/or abstract, leaving 11 articles for full-text review. All full-text articles were reviewed and 6 studies not meeting inclusion criteria (e.g., article on barriers to VMMC access, VMMC demand creation strategies not including incentives) were eliminated.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

We assessed the risk for bias of the quantitative studies following the Guide to Community Preventive Services’ methods for assessing the quality of studies in systematic reviews (The Guide to Community Preventive Services., 2014). Studies were defined as “good” if they had zero or one limitation, “fair” if they had 2–4 limitations, and were excluded if they had 5 or more limitations (The Guide to Community Preventive Services., 2014). The qualitative study included in this review was assessed for bias using an 8-item adapted questionnaire (Blaxter, 1996). The qualitative and quantitative arms of the mixed methods studies included in this review were assessed using the relevant methods indicated above for qualitative and quantitative arms. No articles were excluded due to bias. Table 1 summarizes the five articles included in this review.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the analysis.

| Citation | Country/ Area |

Study type | Duration | Study Aim | Setting | Target Population | Incentive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thirumurthy H., et al. (2014) | Kenya (3 districts in the Nyanza region) | Quantitative | Nine months (June 2013-Feb 2014) | To determine whether small economic compensation could increase circumcision prevalence by addressing reported economic barriers to VMMC and behavioral factors | Urban and rural Nyanza region in Kenya | Adult males aged 25–49 years | A food voucher was given out if participants underwent VMMC within 2 months. Vouchers were given for $2.50, $8.75, and $15.00. |

| Bazant et al. (2016) | Tanzania (Iringa, Tabora, and Njombe regions) | Mixed methods | 3 months | This article describes the evaluation of a lottery incentive for a smartphone and its effects on the volume of VMMC clients compared to the same 3 months during the previous year. | 14 facilities (7 pairs matched within each region) | Men aged 20 years and older | VMMC clients aged 20 years and above learned about the study and lottery incentive in a group information session before the VMMC procedure and were invited to participate when they returnedfor follow-up (within 7 days of their procedure) |

| Wilson et al. (2016) | South Africa | Quantitative | Each postcard had a redemption period of approximately 2 months. Distribution started on June 30, 2014 and all postcards stated an offer expiration date of August 29, 2014. | To measure the effects of information, a challenge, and a conditional cash transfer (economic compensation) on uptake of VMMC. | Soweto, South Africa | Men aged 18 years and older | All subsets of cards included information that refreshments would be provided if clients brought the postcard to the clinic. A subset of cards was offered $10 cash reimbursement, another subset had additional information, and a third subset had a challenge. |

| Thirumurthy et al. (2016) | Kenya | Quantitative | Enrollment took place from April 28, 2014 and September 10, 2014. Data were collected until December 10, 2014. | Assessed whether providing economic compensation for opportunity costs of time or lotterybased incentives can increase male circumcision uptake in Kenya. | Greater Nyando district in the Nyanza region of western Kenya | Uncircumcised men aged 21–39 years | Fixed compensation group: food voucher worth KES 1000 (US $12.50). This amount represents approximated 2–3 days of wages for most men. Lottery-based incentive group: Participants were told that “1 in 20” (5%) would win a bicycle or a smartphone (value of KES 9500, or US $120), “2 in 20” (10%) would win a standard mobile phone or pair of shoes (value KES 3600 or USD $45), and that the remaining 17 in 20 (or 85%) would receive compensation in the form a food voucher worth KES 200 (US $2.50). |

| Evens et al. (2016) | Kenya | Qualitative | Not specified | How provision of economic compensation influenced the decision to get circumcised. | Nyanza region of Kenya | Uncircumcised men aged 25–49 years with no intention to leave the study area in next 3 months | Same as |

Data extraction and management

All studies were coded independently and reviewed for accuracy by two co-authors. The following information was gathered from each study:

Study identification: Author(s); publication year

Study description: Location, target population; study description; type of incentive; study type; study design; sample size; methods; length of the study; and results.

Results

Table 2 summarizes the study characteristics. Studies took place in Kenya (Evens et al., 2016; H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016; H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014), Tanzania (Bazant et al., 2016), and South Africa (Wilson, Frade, Rech, & Friedman, 2016), representing three of the 14 priority countries. The studies included men aged ≥20 years, but the age ranges varied (Table 1). The economic compensation and incentives provided to males included food vouchers of various nominal amounts (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016; H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014), the opportunity to win prizes in a lottery (Bazant et al., 2016; H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016), and cash for transportation reimbursement (Wilson et al., 2016)].

Table 2.

Study design and results: quantitative studies.

| Citation | Sample Size | Study Design (Quantitative) | Relevant outcomes | Methods | Effect of economic compensation or incentive on VMMC uptake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thirumurthy H., et al. (2014) | 1,502 uncircumcised men aged 25–49 years in Nyanza region, Kenya | RCT | The number of VMMCs among men aged 20 years and older during the study period for each site and study group | Participants were randomized to one of four groups: 1. Control: No compensation 2. Group 1: Food voucher of $2.50 3. Group 2: Food voucher of $8.75 4. Group 3: Food voucher of $15.00 |

Participants in the $15.00 group were significantly more likely to get circumcised within 2 months (AOR, 6.2; 95% CI, 2.6–15) compared to the control group. Similarly, participants in the US $8.75 group were also significantly more likely to uptake VMMC (AOR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.7–10.7). Finally, the economic compensation had no effect on VMMC uptake in the US $2.50 group, compared to the control group (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.4–3.5). The effect sizes of the US $8.75 and US $15.00 groups did not differ significantly (P = 0.21), indicating that the higher level of economic compensation was not more attractive. |

| Bazant et al. (2016) | 388 uncircumcised adult men who accessed VMMC services in target facilities in Tanzania | Randomized evaluation using mixed (quantitative and qualitative) methods | The number of VMMCs among men aged 20 years and older during the study period for each site and study group | (1) Control sites: Clients were registered for VMMC and received group educational messages on VMMC. After receiving the procedure, the data are captured and the study team recruited some participants for focus groups. (2) Intervention sites: Clients were registered for VMMC and received group educational messages on VMMC. After receiving the procedure, study staff introduced the study and raffle to each client. On the client’s return visit, if consented for the raffle, he was entered into the raffle joiners log. The study team then recruited some participants for focus groups and follow-up interviews. Raffle occurred once per week for clients and once per month for peer promoters and health providers |

There was a 47% increase in clients who accessed VMMC in the intervention facilities (compared to the previous year) (264 vs. 388) and 8% increase (257 vs. 278) in the control group, respectively. Comparisons of VMMC increases across the two periods, however, were not significantly different. Multivariate analysis indicated that the matched pairs were not statistically different. Subgroup analysis indicated that there was a significant increase in VMMCs (compared to a previous year) in the intervention group in Iringa (exponentiated coefficient 3.36, p < 0.028) and in the control group (exponentiated coefficient 1.63, p < 0.01). |

| Wilson et al. (2016) | 4,000 postcards distributed (divided into 4 study arms of equal size). 74 postcards returned by men seeking VMMC counseling. | Randomized experiment with 4,000 postcard recipients in Soweto (Johannesburg), South Africa. | (1) Calling or texting the VMMC hotline, (2) completing the counseling session, and (3) completing the VMMC procedure. |

Examined differences in uptake of several decisions in the VMMC cascade between the control arm and each of several intervention arms using logistic regression. All postcards offered basic information about the HIV riskreduction benefits of circumcision and clinic hours, and an offer of refreshments for male respondents, aged 18 years and older, who participated in a VMMC consultation. Subsets of these were also offered economic compensation in the form of a conditional cash transfer (i.e., R100, approximately US $10.00), information on a possibly previously unknown benefit of VMMC (i.e., possible partner preference), or a challenge message (i.e., “Are you tough enough?”). | The economic compensation group (offered US $10.00) and the group challenged with “Are you tough enough?” had significantly higher uptake of the VMMC procedure compared to the control group [(OR), 5.30 (CI: 2.20 to 12.76) and 2.70 (CI: 1.05 to 6.91)]. The economic compensation group also had significantly higher uptake of the VMMC counseling session than did the control group [OR 3.76 (CI: 1.79 to 7.89)]. There was no significantly different uptake of either the VMMC counseling session or the procedure in the partner preference information group compared with the control group. Finally, there was no significantly higher use of the VMMC nurse hotline in any intervention group compared with the control group. |

| Thirumurthy et al. (2016) | 903 participants enrolled Control: 301 Fixed-compensation: 308 Lottery-based: 302 | Quantitative | The primary outcome was circumcision uptake within 3 months. | Control group: Participants in the control group were offered compensation of Kenya Shillings (KES) 50 (US $0.60) if they came for circumcision at one of the clinics within 3 months. Fixed compensation group: Participants were informed they would receive a fixed amount of economic compensation (in the form of a food voucher worth KES 1000, or US $12.50) if they underwent circumcision at one of the VMMC clinics within 3 months. Lottery-based group: Participants were informed they would be given the opportunity to participate in a lottery if they underwent VMMC within 3 months. This lottery was designed to have an identical expected value as the fixed compensation amount of US $12.50 and participants were informed about the prizes and probabilities of winning them. Participants were told that “1 in 20” (5%) would win a bicycle or a smartphone (value of KES 9500, or US $120), “2 in 20” (10%) would win a standard mobile phone or pair of shoes (value KES 3600 or USD $45), and that the remaining 17 in 20 (or 85%) would receive economic compensation in the form a food voucher worth KES 200 (US $2.50). |

The group that received economic compensation of US $12.50 had the highest circumcision uptake (8.4%, 26/308), followed by the lotterybased incentive group (3.3%, 10/302), and the control group (1.3%, 4/299). Compared with the control group, the fixed compensation group had significantly higher circumcision uptake [adjusted odds ratio 7.1; 95% CI: 2.4 to 20.8]. The lottery-based incentive group did not have significantly higher circumcision uptake than the control group. |

Three articles presented quantitative data (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016; H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2016), one used mixed methods (Bazant et al., 2016), and one presented qualitative data (Evens et al., 2016) (sub-study of one of the quantitative studies (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016)). One of the two studies in Kenya had four arms: a control arm receiving no economic compensation and three arms receiving food vouchers valued at $2.50, $8.75, and $15 (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014). The economic compensation was provided to 1,502 VMMC clients aged 25–49 years living in three districts in Nyanza region, and accessing services over a 9-month period; and the outcome of interest was VMMC uptake within 2 months of enrollment. The second study conducted in Kenya enrolled 903 participants living in Nyando District in the Nyanza region in three arms: a control arm receiving a 50 Kenya Shillings (KES) (approximately US $0.60) compensation, a fixed compensation group receiving a food voucher worth | KES 1,000 (approximatelyUS $12.50), andathirdarm eligible to participate in a lottery incentive where they could win a bicycle or a smartphone (worth KES 9500, or approximately US $120), or a mobile phone or a pair of shoes (worth KES 3600, or approximately US $45). Those who did not win the main prizes would receive a food voucher worth KES 200 (US $2.50) (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016). The primary outcome of interest was circumcision uptake within three months (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016). Mean participant wealth, measured with an index of 11 items, was low and similar among the samples in both studies, while median daily earnings were lower among the men participating in the study conducted only in Nyando District (3.8) (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016), compared to the study conducted in three districts (5.0) (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014). Another study included in this review investigated the effect of a lottery incentive raffling a smart phone on VMMC uptake among clients was conducted among 388 men in Tanzania over 3 months (Bazant et al., 2016). The final study included in this review involved the distribution of 4,000 postcards with 4 different offers for attendance at a VMMC session in South Africa. Refreshments were offered to all potential clients and subsets were also offered: economic compensation in the form of a CCT ofR100 (approximatelyUS $10) as a transportation reimbursement; information on a possible benefit of VMMC (i.e., possible partner preference); or a challenge message (i.e., Are you tough enough?) (Wilson et al., 2016).

Table 2 summarizes study design and results for the quantitative studies and the quantitative arm of the mixed methods study. The two studies in Kenya concluded that food vouchers may effectively increase VMMC uptake (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016; H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014). The study comparing various amounts of economic compensation found a moderate effect in uptake of the $8.75 and $15.00 vouchers (6.6%; Confidence Interval [CI]= 4.3%–9.5%, and 9.0%; CI = 6.3%–12.4%, respectively) (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014). There was no statistically significant difference between the effect of these food vouchers, indicating that increasing the value from $8.75 to $15 did not significantly increase the effect (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014). The other more recent study conducted in Kenya found that the group receiving a $12.50 food voucher had statistically significant higher circumcision uptake compared to the control group (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]=7.1, CI: 2.4 to 20.8) while the lottery-based group did not (AOR = 2.5, CI: 0.8 to 8.1) (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016). The lottery-based study in Tanzania also did not find a statistically significant effect on uptake (Bazant et al., 2016). This study found that VMMC uptake compared to the same month in the previous year was higher in the intervention (47%) than the control group (8%), but the increase in each group was not statistically significant after controlling for clustering, and the changes were not statistically different (Bazant et al., 2016). Finally, the study providing transportation reimbursement in Soweto, South Africa, found that the group offered $10 transportation reimbursement had higher odds of accessing VMMC (Odds ratio [OR] =5.30, Confidence interval [CI] = 2.20 to 12.76) compared to the control group; as did the group challenged with “Are you tough enough?” compared to the control group (OR = 2.70, CI= 1.05 to 6.91) (Wilson et al., 2016). The analysis did not reveal higher uptake of the VMMC nurse hotline when comparing each of the intervention groups to the control group. Also, when comparing the partner preferences group with the control group, the results do not indicate a statistically significant increase in uptake of the counseling sessions or the VMMC nurse hotline.

Table 3 summarizes the results of the qualitative study and the qualitative arm of the mixed methods study. The qualitative portion of the lottery incentive study conducted in Tanzania entailed six focus group discussions with peer promoters at both intervention and control sites with representation from each region (with a total of 32 peer promoters), and six focus groups with clients (with a total of 40 VMMC clients) who returned for follow-up within 7 days of VMMC (Bazant et al., 2016). Clients suggested that economic compensation would be preferable to a raffle incentive, and the phone (as a prize) was found undesirable by all participants. Some men suggested that receiving free, high-quality VMMC services was incentive enough. Furthermore, some were suspicious about reasons why they were entered into a raffle incentive to win a phone in addition to receiving free medical services.

Table 3.

Study results: qualitative study and qualitative arm of mixed methods study.

| Citation | Sample Size | Study Design Details (Qualitative) | Qualitative results relevant to effectiveness of economic compensation or incentive (for mixed methods studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evens et al. (2016) | 45 circumcised and uncircumcised male participants and 19 female partners | Follow-up interviews | Interviews revealed that economic compensation promoted VMMC uptake by addressing lost wages during and after the circumcision procedure. Participants who became circumcised fit into one of 3 main categories: (1) those for whom the offer of food vouchers was highly influential in their decision because it addressed their financial concerns, (2) those who said that they had already decided to get circumcised before the intervention but the offer of the food voucher made it easier to go, and (3) those who said they were motivated to access VMMC by conversations with the study staff and the information received about VMMC. Participants who did not get circumcised perceived the economic compensation amounts to be insufficient or reported having nonfinancial barriers that were not addressed by the intervention, such as fear of pain. The vast majority of partners of both circumcised and uncircumcised participants were supportive of their partners getting circumcised. No participants perceived the amount of economic compensation to be so high that they could not turn it down. All indicated that the economic compensation amounts were either too little or the right amount. |

| Bazant et al. (2016) | 32 peer promoters, 40 VMMC clients who returned for follow-up within 7 days | 6 focus groups with clients and 6 with peer promoters at both intervention and control sites with representation from each region (with a total of 32 peer promoters). Forty VMMC clients who returned for follow-up within 7 days of VMMC participated in focus group discussions of up to 8 participants each. | Clients suggested that economic compensation for all clients would be preferable to an incentive in the form of a raffle, and the phone was found not to be desirable by all participants. Economic compensation in the form of cash was recommended. Some men suggested that receiving free good-quality services was sufficient. Furthermore, a few participants were suspicious about the reasons why they were receiving free services, free medication and, in addition, some were also receiving a phone. |

The qualitative study of the food voucher study conducted in Kenya revealed that economic compensation promoted circumcision uptake by addressing lost wages during and after VMMC (Evens et al., 2016). Participants who became circumcised fit into one of the following categories: (1) those for whom the offer of food vouchers was highly influential as it addressed financial concerns, (2) those who said that they had already decided to get circumcised before the intervention but that the offer of the food voucher made it easier to go, and (3) those who said they were motivated to access VMMC by conversations with the study staff and the information received about VMMC. Participants who did not get circumcised perceived the economic compensation amounts to be insufficient or reported having nonfinancial barriers, such as fear of pain. No participants perceived the amount of compensation to be coercive. All indicated that the compensation amounts were either too little or the right amount. The vast majority of partners of both circumcised and uncircumcised participants were supportive of their partners getting circumcised (Evens et al., 2016).

The studies addressed ethical considerations to varying degrees. One qualitative study included in this review investigated the possibility of undue influence (to obtain compliance through inappropriate reward or other overture) and found that the economic compensation offered was considered to be the right amount or low (Evens et al., 2016). Other studies integrated ethical considerations in the design of the economic compensation. For example, in the study providing transportation reimbursement in Soweto, South Africa, researchers avoided any potential ethical challenges by offering economic compensation that was contingent on accessing an information session rather than getting circumcised (Wilson et al., 2016). In the food voucher study conducted in Kenya, the largest food voucher amount offered was comparable to likely costs associated with circumcision (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2014). Ethical considerations and coercion were explicitly mentioned in one study conducted in Kenya, which indicated that no participants were circumcised during the study period who had previously expressed no interest in VMMC (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016). Thus, the research indicates that economic compensation and incentives did not unduly influence participants, but it likely encouraged those who were already considering VMMC (H. Thirumurthy et al., 2016).

Discussion

The results indicate that there is a paucity of evidence about the effect of various types of economic compensation and incentives for clients on increasing VMMC uptake. We only found five relevant studies, and four of them were conducted in Kenya and Tanzania, where uptake of VMMC in various regions is close to reaching the 80% target set in 2011 (WHO, 2015). Given the success of VMMC scale-up in these two countries, the conclusions from the studies might not be generalizable to settings with lower VMMC prevalence (Carrasco & Wilkinson, 2016). It is possible that once a certain threshold of VMMC coverage has been reached, economic compensation and incentives can help encourage men who have not yet undergone male circumcision to access VMMC services. This might be due to addressing financial barriers and lost wages, or providing additional encouragement to access VMMC services among late adopters. Indeed, economic compensation and incentives may prove to be most cost-effective in contexts where a certain VMMC threshold has been reached to ensure that the economic compensation and incentives are targeted to those who would not have accessed the service otherwise. Further research is needed to better understand the effect of economic compensation and incentives in countries with suboptimal VMMC uptake, especially among men at different stages of readiness for VMMC and of different ages.

An important consideration is that the economic compensation and incentives provided in these studies included were not provided in a vacuum but in environments where participants likely had access to information about VMMC prior to the studies. Indeed, there have been significant demand creation efforts in the VMMC priority countries using communications strategies such as community mobilization through interpersonal communications and radio spots. In such settings, the results indicate that economic compensation in the form of cash and food vouchers of small nominal amounts may effectively increase VMMC demand, while incentives in the form of lotteries do not. Furthermore, qualitative evidence indicated that potential VMMC clients prefer cash transfers rather than lotteries. These results highlight the importance of thorough formative research to determine if compensation or incentives would be attractive to the target population in a particular context.

Additionally, given the potential for unduly influencing clients into accessing VMMC, these studies highlight the importance of setting the value of economic compensation and incentives at an amount that is attractive enough to motivate those who are seriously contemplating VMMC but does not unduly influence clients. Furthermore, given the potential for misuse, researchers and practitioners could turn to existing models to assess the ethics of applying strategies that include economic compensation and incentives. Grant and Sugarman (2004) proposed five conditions to assess if the use of economic compensation and incentives in research is unethical (Grant & Sugarman, 2004). These included situations in which (1) the participant was in a dependent relationship with the researcher, (2) the risks of the intervention were high, (3) the research was degrading, (4) the participant would only consent if the economic compensation or incentive was relatively large because the participant’s aversion to the study was strong, and (5) the participant’s aversion is based on his/her principles (Grant & Sugarman, 2004). While this framework is useful, it applies to research and not to the uptake of free, voluntary services, as is the case with VMMC. Krubiner (2015) provides a framework to assess the ethics of a conditional cash transfers for programs through assessing, refining, and re-evaluating the program conditionalities during the design, implementation, and adjustment of the program (Krubiner, 2015). Indeed, if economic compensation or incentives are used, they should be designed following a systematic process to determine type, amount, and to ensure they are appropriate to the local context.

In addition to ethical considerations, sustainability is another practical consideration that should be considered when including economic compensation or incentives as part of strategies to increase VMMC uptake. While VMMC services have primarily been funded by donors such as PEPFAR and the World Bank, the provision of services will likely be transferred to country governments that may not support economic compensation or incentives. However, it is possible that once VMMC prevalence has reached the 80% saturation goal in priority age groups and VMMC has become a social norm, maintenance of VMMC prevalence among boys and infants may not require the use of economic compensation or incentives. Taking sustainability considerations into account, it would be prudent to involve the local Ministry of Health coordinating VMMC services in deliberations about the introducing economic compensation or incentives. One consideration is that smaller amounts are likely to be more sustainable and cause less disruption if discontinued.

Finally, it is important to monitor any negative effects that may be caused by economic compensation or incentives. For example, it is possible that economic compensation or incentives for particular age groups could create a disincentive for men in younger age groups from accessing VMMC, as they may prefer to postpone circumcision in order to be eligible to receive the economic compensation or incentive. Additionally, if not implemented carefully, economic compensation and incentives could change dynamics around personal responsibility for one’s health and create an expectation for remuneration for other health services. This emphasizes the importance of setting an amount for economic compensation and incentives that is not too high, to avoid creating counterproductive externalities.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of USAID or CDC.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, & Puren A. (2005). Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 trial. PLoS Medicine, 2(11), e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN,… Ndinya-Achola JO. (2007). Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 369(9562), 643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, & Özler B. (2012). Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: A cluster randomised trial. The Lancet, 379(9823), 1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazant EDMPH, Mahler HMPH, Machaku MM, Lemwayi RDDSMPH, Kulindwa YM, Gisenge Lija JMDM,… Epi MP. (2016). A randomized evaluation of a demand creation lottery for voluntary medical male circumcision among adults in Tanzania. [Article]. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(4), S285–S292. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. (1996). Criteria for the evaluation of qualitative research papers. Medical Sociology News, 22(1), 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Boccia D, Hargreaves J, Lonnroth K, Jaramillo E, Weiss J, Uplekar M,… Evans . (2011). Cash transfer and microfinance interventions for tuberculosis control: Review of the impact evidence and policy implications. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 15(Supplement 2), S37–S49. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco MA, Nguyen T, & Kaufman MR (2016). Low uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision among high risk men in Malawi. Under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco MA, & Wilkinson J. (2016). Systematic review of the barriers and facilitators to voluntary male medical circumcision uptake in priority countries and recommendations. Under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikutsa A, Ncube AC, & Mutsau S. (2015). Association between wanting circumcision and risky sexual behaviour in Zimbabwe: Evidence from the 2010–11 Zimbabwe demographic and health survey. Reproductive Health, 12, e298. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0001-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evens E, Lanham M, Hart C, Loolpapit M, Oguma I, & Obiero W. (2014). Identifying and addressing barriers to uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision in Nyanza, Kenya among men 18–35: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 9(6), e98221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evens E, Lanham M, Murray K, Rao S, Agot K, Omanga E, & Thirumurthy H. (2016). Use of economic compensation to increase demand for voluntary medical male circumcision in Kenya: Qualitative interviews With male participants in a randomized controlled trial and their partners. [Article]. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(4), S316–S320. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, & Neufeld LM (2008). Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: An analysis of Mexico’s oportunidades. The Lancet, 371(9615), 828–837. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60382-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaarder MM, Glassman A, & Todd JE (2010). Conditional cash transfers and health: Unpacking the causal chain. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 2(1), 6–50. doi: 10.1080/19439341003646188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RW, & Sugarman J. (2004). Ethics in human subjects research: Do incentives matter? The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 29(6), 717–738. doi: 10.1080/03605310490883046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F,… Chen MZ. (2007). Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in rakai, Uganda: A randomised trial. The Lancet, 369(9562), 657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Guide to Community Preventive Services. (2014). Systematic review methods. Retrieved from http://thecommunityguide.org/about/methods.html

- Health Communication Capacity Collaborative. (2016). Technical considerations for demand generation for VMMC in the context of the age Pivot. J. H. C. f. C. Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Roloff A, Llewellyn E, Obiero W, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola J, Muraguri N, & Bailey RC (2011). Implementing voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in Nyanza Province, Kenya: Lessons learned during the first year. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e18299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Roloff A, Otieno N, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola J, & Bailey RC (2011). Acceptability of medical male circumcision among uncircumcised men in Kenya one year after the launch of the national male circumcision program. PLoS One, 6(5), e19814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H-P, & Thornton RL (2012). Conditional cash transfers and HIV/AIDS prevention: Unconditionally promising? The World Bank Economic Review, 26(2), 165190. Retrieved from http://wber.oxfordjournals.org/content/by/year doi: 10.1093/wber/lhr041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke K, Okello V, Maziya V, Benzerga W, Mirira M, Gold E,… Njeuhmeli E. (2016). Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in Swaziland: Modeling the impact of Age targeting. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0156776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke K, Opuni M, Schnure M, Sgaier S, Castor D, Reed J,… Stover J. (2016). Age targeting of voluntary medical male circumcision programs using the decision makers’ program planning toolkit (DMPPT) 2.0. PloS one, 11(7), e0156909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubiner C. (2015). Which strings attached? Toward an ethics framework for selecting conditionalities in conditional cash transfer programs (Doctor of Philosophy), Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde M, Haines A, & Palmer N. (2007). Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Jama, 298(16), 1900–1910. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, & Gakidou E. (2010). India’s janani suraksha yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: An impact evaluation. The Lancet, 375 (9730), 2009–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre K, Andrinopoulos K, Moses N, Bornstein M, Ochieng A, Peacock E, & Bertrand J. (2014). Attitudes, perceptions and potential uptake of male circumcision among older men in Turkana county, Kenya using qualitative methods. PLoS One, 9(5), e83998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler HR, Kileo B, Curran K, Plotkin M, Adamu T, Hellar A,… Lukobo-Durrell M. (2011). Voluntary medical male circumcision: Matching demand and supply with quality and efficiency in a high-volume campaign in Iringa region, Tanzania. PLoS Medicine, 8(11), e1001131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Group P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269, W264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano DE, Kasprzyk D, Hamilton DT, Tshimanga M, & Gorn G. (2014). Evidence-based identification of key beliefs explaining adult male circumcision motivation in Zimbabwe: Targets for behavior change messaging. AIDS and Behavior, 18(5), 885–904. doi: 10.1007/s10461013-0686-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Hughes JP, Selin A, Wang J, Gomez-Olive FX,… Khoza N. (2016). The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 4(12), e978–e988. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30253-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Nguyen N, & Rosenberg M. (2012). Can money prevent the spread of HIV? A review of cash payments for HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 16(7), 1729–1738. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin M, Castor D, Mziray H, Kuver J, Mpuya E, Luvanda PJ,… Mahler H. (2013). “Man, what took you so long?” social and individual factors affecting adult attendance at voluntary medical male circumcision services in Tanzania. Global Health: Science and Practice, 1(1), 108–116. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-12-00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie S, Perry B, Corneli A, Chilungo A, & Umar E. (2015). Perceptions of voluntary medical male circumcision among circumcising and non-circumcising communities in Malawi. Global Public Health, 10(5–6), 679–691. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1004737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssekubugu R, Leontsini E, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, Kennedy CE,… Gray RH. (2013). Contextual barriers and motivators to adult male medical circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. Qualitative Health Research, 23(6), 795–804. doi: 10.1177/1049732313482189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurthy H, Masters SH, Rao SO, Bronson M, Lanham M, Omanga E, . Agot K. (2014). Effect of providing conditional economic compensation on uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision in Kenya: A randomized clinical trial. Jama, 312(7), 703–711 doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurthy H, Masters S, Rao SO, Murray K, Prasad R, Zivin JG,… Agot K. (2016). The effects of providing fixed compensation and lottery-based rewards on uptake of medical male circumcision in Kenya: A randomized trial. [Article]. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(4), S309–S315. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USAID, W. B. (2010). The ethics of material incentives for HIV prevention. Emerging issues in Today’s HIV Response: Debate 5. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTHIVAIDS/Resources/375798-1297872065987/WorldBankUSAIDDebate5Report.pdf

- Westercamp M, Agot KE, Ndinya-Achola J, & Bailey RC (2012). Circumcision preference among women and uncircumcised men prior to scale-up of male circumcision for HIV prevention in Kisumu, Kenya. AIDS Care, 24(2), 157–166. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.597944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2015). Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in 14 priority countries in East and Southern Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2016). Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in 14 priority countries in east and Southern Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246174/1/WHO-HIV-2016.14-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNAIDS. (2007). New data on male circumcision and HIV prevention: Policy and programme implications. Geneva: WHO; Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/mc_recommendations_en_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NPMPA, Frade SMMPDM, Rech DMD, & Friedman WP (2016). Advertising for demand creation for voluntary medical male circumcision. [Article]. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(4), S293–S296. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]