Abstract

Background

Community–academic partnerships are an increasingly popular approach to addressing community health problems and engaging vulnerable populations in research. Despite these altruistic foci, however, partnerships often struggle with fundamental issues that thwart sustainability, effectiveness, and efficiency.

Objectives

We adapted a synergy-promoting model to guide the development and evaluation of a community–academic partnership and share lessons learned along the way.

Methods

We analyzed the partnership process over time to determine the interaction of trust, collaboration, and engagement in creating partnership synergy and promoting sustainability.

Lessons Learned

Few community–academic partnerships use a conscious and systematic approach to guide and evaluate their progress. We argue that this is an important first step in creating a partnership, sustaining a milieu of open dialogue, and developing strategies that promote trust and equalize power dynamics. Still, as we learned, the best laid plans can go awry, challenging partnership synergy throughout its lifespan.

Keywords: Nursing community health partnerships, community-based participatory research, community health research, power sharing process issues

Many communities around the United States face exigent health problems that are unresponsive to single-solution programs or top-down strategies, resulting in the use of community-based participatory research (CBPR) as a framework to address them.1 In this approach, community and academic partners come together to accomplish results that might be difficult or impossible to achieve alone; pooling resources, mobilizing each other’s best talents, and diversifying approaches to problems to enhance interventions and improve outcomes.2

Community–academic partnerships have demonstrated success in health promotion, illness prevention and disease management,3,4 health education,5 health screening,6,7 and enhanced utilization of health services.8,9 As “reciprocal interactional collaborations,”10(p. 266) partnerships between University researchers and community stakeholders are most effective in designing interventions to meet community needs11 and promoting community empowerment.12,13 A CBPR framework is particularly salient when including vulnerable populations who have not historically engaged in health-related research.14 A community–academic partnership that embraces CBPR, therefore, can facilitate the engagement of vulnerable populations and develop culturally and contextually appropriate interventions that improve health outcomes among diverse populations.15–20

One of the greatest challenges to community–academic partnerships is their long-term sustainability. A partnership often begins as a relationship between individuals who share common ideas. This is a particularly susceptible period; if one of the individuals leaves or cannot attend to the relationship early on, the partnership may go no further. As the individual relationship blossoms, the idea is to move the process from an individual connection to a systemic alliance. Even if this transition occurs, however, difficulties can arise that threaten the partnership’s infrastructure and ability to achieve significant measurable outcomes.21,22

Part of the problem with sustainability is that few partnerships use a conscious and systematic approach to guide their development and progress. We argue that this is an important first step; a theoretical framework can guide the development of a community–academic partnership and monitor its integrity along the way. Because of its closely matched principles of CBPR, we adapted Lasker, Weiss, and Miller’s23 partnership synergy model for collaboration for use as the guiding framework for our new community–academic partnership. We examined the components known to foster partnership synergy: collaboration, engagement, and trust, and how these elements intersected, both positively and negatively, over the partnership’s first year of operation.

METHODS

The Theoretical Framework

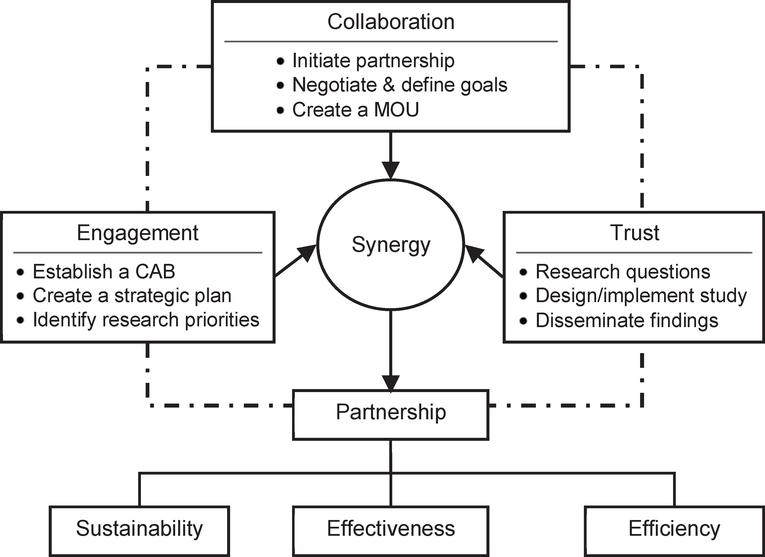

In their model, Lasker et al.23(p. 183) describe synergy as “the power to combine perspectives, resources, and skills of a group of people and organizations” and view it as a proximal outcome and distinguishing feature of collaboration. In our iteration, although synergy remains at the core of a successful partnership, we place greater emphasis on the balance of collaboration, engagement, and trust in preserving partnership integrity. Th us, rather than viewing synergy as an end result, we consider it a dynamic indicator of partnership sustainability, effectiveness, and efficiency. In Figure 1, we describe the characteristics of the model and how they were defined and applied.

Figure 1. Characteristics of the Synergy Model in Developing Community-Academic Partnerships.

Note. Adapted from Lasker et al.23

In our adaptation, collaboration represents how the partnership functions and how power is perceived, utilized, and shared between partnering entities. In a truly collaborative relationship, full reciprocity exists at all levels with an elimination of power differentials. This is a challenging task because individuals within the partnership bring their own expertise to the table and may hold preconceived notions of each other’s level of understanding, knowledge, and proficiency.24,25 Community partners, for example, may view academicians as isolated researchers in ivory towers, whereas researchers may underestimate their community partner’s research acumen. Academic partners need to become engaged with the community by learning about the environment, participating in activities in the facility, and interacting regularly with community members.26,27 Conversely, community partners need to understand the faculty member’s role, how research pertains to job performance, and how teaching and service compete for the academic’s time. Norris et al.28 suggest that partners create a memorandum of understanding that clearly describes the partners’ roles and responsibilities, the processes and procedures guiding the partnership, and a timeline to benchmark and evaluate partnership integrity.

Engagement is thus the full participation of all partner members such that the relationship moves from one between individuals to a community of individuals. Creation of a community advisory board is a critical next step in achieving this aim. Including individuals from both the university side and the target community as community advisors is instrumental in developing and implementing sustainable community–academic partnerships that prioritize the community’s needs rather than the researcher’s agenda.29 Community advisors need to be credible within the target community, able to liaison with the community and other stakeholders, and willing to help develop a strategic plan for the partnership.28,30 They must also be actively engaged in all aspects of the research process, including problem identification, designing the methodology, collecting, organizing and analyzing data, and disseminating the findings. The upfront time and effort creating the community advisory board has had measurable payoff in increasing trust,31 engaging the community in the research process,7 and ensuring scientific rigor.32

Although evidence shows that partnerships grounded in trust can engage vulnerable and underserved communities, many underserved groups are reluctant to engage in partnerships with academic institutions because of mistrust related to perceived racism and bias in research methodologies.33–37 African Americans, in particular, describe a lack of perceived benefit to participating in research7,17,35 and raise concerns about exposure to harmful risk.38,39

Putting Theory into Practice

We used the modified synergy model to develop a new partnership between the University of Michigan and University of Detroit Mercy schools of nursing and the Family Care Network, a nonprofit agency serving the social, service, and housing needs of homeless families and older adults living in Detroit, Michigan. In early 2008, the Family Care Network identified an interest in expanding its service efforts to include health promotion activities that nurses might provide. The agency’s Vice President of Services and two nursing faculty members met initially to discuss their interests and the feasibility and purpose of a community–academic partnership.

After several meetings, the group identified shared goals for collaboration and applied for a pilot grant to support them. As part of the grant submission, and in keeping with the tenets of the synergy model, we proposed the development of a memorandum of understanding and a community advisory board consisting of 10 members from both partner entities, including the principal investigators, a project manager, community members, and nursing students. We wanted adequate representation with a moderately sized group to ensure broad and balanced perspectives but have a manageable work group that could bond over time.

With the grant under review, we organized the community advisory board and arranged its first meeting in August 2008. We discussed the proposed partnership and its overall purpose: to elicit the health and social needs of the community-served from the perspective of the community itself. To do this, we proposed 8 focus groups with community service providers and service recipients of both the homeless family and older adult programs to elicit their views of the problems they faced and how they should be addressed. A secondary goal was to determine the study participants’ perspectives about research more broadly and their willingness to participate in research endeavors. We discussed the role of the community advisory board and established a time line of monthly follow-up meetings. Meeting minutes were taken and later distributed to all board members to monitor the groups’ progress, establish participation trends, and ensure ongoing communication.

These initial efforts corresponded with the collaboration element of the synergy model in establishing a functional framework for the partnership’s growth. While waiting for a funding decision, however, we also recognized that it was a particularly vulnerable time in the partnership’s development; although the underlying aims of the collaboration had taken shape, the partnership was essentially “on hold” until we had the resources necessary to initiate the key elements of the process. Critical in this stage was sustained interaction and communication to ensure that the partnership did not lose steam during this period.

With funding awarded in September 2008, we moved into the engagement phase of the synergy cycle. This entailed garnering the community’s perspectives about its health and the role research might play in addressing identified problems. While awaiting Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Michigan and University of Detroit Mercy to conduct the focus groups, the community advisory board met to fine tune the interview questions, discuss subject recruitment and incentives, and continue dialogue about the partnership’s direction and focus. We decided to draft the memorandum of understanding at our October meeting.

Just before the October 2008 meeting, however, we hit an unanticipated complication; our community investigator’s position was cut in an effort to save agency costs. Because the collaboration was only months old, we worried that the partnership would end before it really began. We quickly convened a community advisory board meeting to discuss how best to proceed. Fortunately, over the next month, the community partner created her own nonprofit agency, Community and Home Supports, and assumed leadership as chief executive officer. All contractual arrangements with the homeless family and older adult programs were transferred from Family Care Network to Community Home Supports and, with a surprisingly seamless transition, we were able to move ahead. The only modification involved reconfiguring the community advisory board given that one member was no longer part of the redesigned organization and amending our institutional review board application to reflect the new agency.

RESULTS

With institutional review board approval from both academic settings, we began data collection in December 2008 and completed our focus groups in April 2009. The focus group sessions were conducted, transcribed, and analyzed by 4 community advisory board members with expertise in qualitative research.

Our findings revealed information that helped us understand new and ongoing problems and how current services did or did not address them. For example, in the groups with homeless program service providers (n = 10), we discovered a universal commitment by the workers to help families secure housing quickly while dealing with the frustration of limited housing availability. Themes centered primarily on job-related issues, concerns with the “system” at large, and issues with the clients they served. Service providers noted that many of the city’s resources for the homeless were not “family centric,” “fostered dependence over empowerment,” and were “redundant” and “inflexible.” These limited resources, they opined, led their clients to develop a “helpless mindset” that undermined their abilities to succeed in education, employment, and long-term housing stability.

Homeless service recipients (n = 15) echoed similar concerns with services, although they did not reflect at all the helplessness and hopelessness depicted by service providers. Instead, they talked about “getting through it” and “doing what they had to do” to refocus their current situations from destitution to success. They wanted us to understand that they were “more than someone without a home” and that they worried deeply about the effect of homelessness on their children. They viewed education as an important avenue to change and many were seeking high school completion or entry into higher education. They also discussed at length the difference between “affordable” and “suitable” housing and how certain systemic barriers (e.g. lack of transportation, difficulty securing birth certificates, former criminal records) made it difficult to succeed. They were appreciative of the support and services received through the agency and recognized its role in changing their lives.

Participants in the older adult care worker focus groups (n = 8) also revealed areas of concern with their jobs, the system within which they worked, and their clients. Although generally happy with their service roles, they worried about their livelihoods as funding for home-based services waned. Many worked part time, were older themselves (age range 50–78), had health problems that made some activities increasingly difficult (e.g., arthritis and lifting clients), and had limited or no health insurance. Several reported that they often faced situations for which they felt unprepared but “did the best they could.” For example, one participant described caring for a woman with a “colostrophe” that started leaking. Her supervisor, also unfamiliar with colostomy care, could offer little advice and thus she managed to the best of her ability to help her client. Others chimed in with their own stories and suggested that they would benefit from more in-service education on certain topics (e.g., working with Alzheimer’s clients or the developmentally disabled) or the ability to contact a health care professional when needed.

The older adult focus groups proved to be our most difficult as many of the agency’s clients were unable to consent or were too frail to participate. After careful deliberation with the community advisory board, we conducted our focus groups with individuals living in a senior housing apartment building, knowing that they would not be representative of the myriad clients served. Indeed, we found this group to be rather high functioning compared with the clients described by the service providers. Many of the groups’ participants (n = 9), now in their late 70s and 80s, had lived in the building for several decades. They described their health problems and the need for supportive services to maintain their homes and independence. They worried about transportation, safety, and loneliness as they lost their partners and friends. Many struggled with depression and motivation to leave their apartments and engage in activities. One male participant, whose wife had died 8 years earlier, shared, “You don’t realize what depression is until you lose somebody. And then … you don’t realize that you’re actually in that mode yourself. You could read about it [depression] all day long and you say, ‘Oh, that can’t happen to me.’”

In keeping with our overarching conceptual framework, results were brought to the larger group for discussion. Because some of the study participants were employees or service recipients who worked directly with or reported to some community advisory board members, we were careful to retain confidentiality, particularly if a participant raised concerns about the agency, the services provided, or its leadership.

We were also careful to differentiate the findings as evidence for further assessment and intervention rather than as an evaluative process of the agency, its work, and its workers. The community advisory board began to prioritize the information to determine next best steps; this drove the submission of two other grants to support the agency’s work, and fostered creation of smaller teams to work on publications and presentations.

Processing the Process

It was during this latter phase of our collaboration, however, that we noticed subtle detachment among two community advisory board members who worked in agency service administration. Although they regularly attended meetings, they became noticeably less engaged. At first, we attributed this to the shifting emphasis of our work; in the early stages of our collaboration, both individuals played key roles in recruiting study subjects and determining appropriate questions and incentives. As other community advisory board members became more involved in the actual process of collecting, collating, and interpreting data, however, the two members contributed less often. In response to this observation, we discussed group dynamics at the May 2009 meeting and asked members to comment on their community advisory board experiences. Neither individual volunteered to speak; at the June 2009 meeting, one did not attend and the other resigned. Clearly, we missed something in the dynamic that thwarted their ability to remain engaged. When we reflected on this in relation to the synergy partnership model that we employed, it was evident that there remained issues of trust that ultimately thwarted engagement and collaboration. This breakdown has the potential to undermine the synergistic collaborative relationship and result in an erosion of a sustainable partnership.

We later learned that one member had not joined the community advisory board voluntarily, but had been assigned to do this as part of her job. The second individual had willingly participated, but later confided to the project manager her desire to have a larger role in data collection and management. This revelation was surprising; the community advisory board participated in all aspects of the research process and the member had numerous opportunities to verbalize her interests. We discovered that neither individual felt comfortable expressing her feelings and ideas fully, however, because one of the project co-investigators was their direct superior. We had spent considerable effort attempting to equalize the power gradient across organizations, but had failed to note the hierarchies that existed within the organizational structure that may have made frank discussion uneasy for these individuals. This oversight may have marginalized members who perceived themselves as less powerful than others. Thus, although most of the community advisory board members worked together synergistically, these members disengaged and did not feel comfortable expressing themselves.

On the other hand, the group’s dissolution may have been part of its natural evolution. It is understandable that as the group’s goals shifted over time, so too would individuals’ interests and investment. Indeed, the two individuals’ disengagement occurred when the community advisory board was in the beginning stages of transition to a research advisory group, whose aim was to plan and procure research funding. It may well be that some of the functions of that transformed group did not interest the individuals who resigned.

Indeed, when the group transitioned from a community advisory board to a research advisory group in September 2009, the shifting nature of partnerships such as these became even more apparent. Although the three core investigators and two other community advisors continued as active research advisory group participants, the project manager left to attend school and the students graduated. Still, we continued to meet monthly, established a new set of directions for our continued work together and, with new funding in hand, invited three new community members, a graduate nursing student, another nurse faculty member, and a social work intern to join the research advisory group team. We continue to meet monthly and remain optimistic that adherence to our model will guide future efforts.

LESSONS LEARNED

Despite the use of a guiding framework to develop and monitor the process and progress of our community–academic partnership, we faced challenges to the partnership’s integrity throughout the period of analysis. First, we learned that it takes time to achieve trust between members leading to full engagement and collaboration, and that with each iteration of the partnership’s membership, we must pay conscious attention to these critical elements to achieve and sustain synergy. Thus, along with fostering ongoing dialogue, we need to continuously evaluate group process to recognize and address disengagement early on and be aware of power dynamics that may derail progress.

We also learned that power differentials will always be present in relationships, whether between or within organizations and their members.22 Ameliorating those power gradients to create synergistic partnerships, however, is critical to creating and sustaining collaboration, trust, and engagement. More important is to recognize that partnerships are always evolving and require constant nurturing in a flexible and accepting milieu. Change is inevitable over time and should be anticipated as part of the partnership process. As we shared from our experience, change occurred at several points, creating pressure to adapt or, in some cases, reprioritize or redirect partnership goals. Indeed, how power and change are managed by partnership members ultimately determines the partnership’s viability and sustainability.

Academic and community partners view the community with different lenses. This differing world view can be both an advantage and a disadvantage in the partnership process. The advantage of this wider view is its potential to increase the breadth and depth of understanding of community issues and how to address them. The disadvantage is that partners may struggle with consensus on what issues are most important. Using focus groups and qualitative methods to acquire an understanding of the community’s perceived social and health needs was an important step but we must be more cognizant of how partners come together to plan, design, and implement follow-up interventions and programs. In other words, research and practice have complementary perspectives and skills that need to be used together to maximize partnership sustainability.

Our use of Lasker et al.’s partnership synergy model is but one example of how to consciously and systematically assess areas that increase trust, collaboration, and engagement to move partnerships from separate entities to synergistic collaborations. Our use of this model kept us focused on issues related to trust, engagement, and collaboration. The failure of some members to trust clearly impeded their ongoing engagement and had the potential to undermine the collaboration process. Our diligent attention to the partnership synergy model, however, enabled us to quickly recognize the area of breakdown and continue to move toward a sustainable collaborative partnership. Thus, we found the model to be not only a helpful guide in the initial development of the partnership, but as an ongoing evaluation tool for partnership growth.

Other theoretical approaches may prove more effective depending on the local culture of the partnership and how partners wish to build collaborative relationships. Regardless of the framework used, it is essential that all partners enter the relationship with a goal to maximize the partnership’s best practices as well as its best processes and adhere carefully to the tenets of relationship building in doing so. Only then can research effectively and efficiently translate into practices that improve the health of vulnerable communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support provided by the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (MICHR, UL1RR024986), and the Michigan Center for Health Intervention (MICHIN, 5P30NR009000) in the conduct of this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also thank and acknowledge the support of the members of the Community Advisory Board during this process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Green LW, Mercer SL. Can public health researchers and agencies reconcile the push from funding bodies and the pull from communities? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1926–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SM, Shortell SM. The governance and management of effective community health partnerships: a typology for research, policy, and practice. Milbank Q. 2000;78:241–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving public health. Annu Rev Pub Health. 2000;21:369–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silka L Partnerships within and beyond universities: Opportunities and challenges. Public Health Rep. 2004; 119:73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellenbecker CH, O’Brien E, Bryne K. Establishing partnerships with social service agencies for community health education. J Commun Health Nurs. 2002;19:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busen NH, Beech B. A collaborative model for community-based health care screening of homeless adolescents. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13:316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Bari M, Suggs PK, Holmes LP, et al. Research partnership with underserved African American communities to improve the health of older persons with disability: a pilot qualitative study. Aging Clin Exper Res. 2007;19:110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzler MM, Higgins DL, Beeker CG, et al. Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:803–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells KB, Staunton A, Norris KC, et al. Building an academic-community partnered network for clinical research: the community health improvement collaborative (CHIC). Ethn Dis. 2006;16:S1–3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crist J, Escandón-Dominguez S. Identifying and recruiting Mexican American partners and sustaining community partnerships. J Trans Nurs. 2003;14:266–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savage CL, Xu Y, Lee R, Rose BL, Kappesser M, Anthony JS. A case study in the use of community-based participatory research in public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:472–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laverack G, Labonte R. A planning framework for community empowerment goals within health promotion. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy SR, Baldyga W, Jurkowski JM. Developing community health promotion interventions: selecting partners and fostering collaboration. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4:314–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesser J, Oscós-Sánchez MA. Community-academic research partnerships with vulnerable populations. Ann Rev Nurs Res. 2007;27:317–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker EA, Homan S, Schonhoff R, Krueter M. Principles of practice for academic/practice/community research partnerships. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16 Suppl 3:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce SA, Austin-Ketch T. Community-based participatory research: an exemplar of learning. Am J Nurs Pract. 2006; 10:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dancy BL, Wilbur J, Talashek M, Bonner G, Barnes-Boyd C. Community-based research: barriers to recruitment of African Americans. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52:234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowles ER. Collaborative methodologies for advancing the health of underserved women. Fam Commun Health. 2007; 30 Suppl 1:S53–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pestronck R, Franks M. A partnership to reduce African American infant mortality in Genessee County, Michigan. Public Health Rep. 2003:118:324–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Parker EA, Lockett M, Hill Y, Wills R. The East Side Village Health Worker Partnership: integrating research with action to reduce health disparities. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:548–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butterfoss FD, Francisco VT. Evaluating community partnerships and coalitions with practitioners in mind. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindamer LA, Lebowitz B, Hough RL, et al. Establishing an implementation network: Lessons learned from community-based participatory research. Implementation Science. 2009;4:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: A practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79:179–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minkler M Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82:ii3–ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter J, Baker EL. The management moment partnering essentials. J Public Health Man Pract. 2005;11:174–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scharff DP, Mathews K. Working with communities to translate research into practice. J Public Health Man Pract. 2008;14:94–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson LS, Story M, Butler G. Use of a university–community collaboration model to frame issues and set an agenda for strengthening a community. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4:385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, Miranda J, Duru K, Mangione CM. Partnering with community-based organizations: an academic institution’s evolving perspective. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:S1–27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez AR, Gutiérrez L. Choosing to do participatory research: an example and issues of fit to consider. J Commun Pract. 2001;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1938–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dennis BP, Neese JB. Recruitment and retention of African American elders into community-based research: lessons learned. Arch Psych Nurs. 2000;14:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topp R, Newman JL, Jones VF. Including African Americans in healthcare research. Western J Nurs Res. 2008;30:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goode TD, Harrison S. Cultural competence in primary health care: partnerships for a research agenda [Policy Brief 3]. Washington (DC): National Center for Cultural Competence; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shavers VL, Lynch C, Burmeister L. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Earl CE, Penney PJ. The significance of trust in the research consent process with African Americans. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23:753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen LA. Racial differences in trust: reaping what we have sown? Med Care. 2002;40:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DM. Distrust, race and research. Ann Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freimuth VS, Quinn CS, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans’ views and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]