Abstract

In this study, we respond to calls for strengths-based Indigenous research by highlighting American Indian and First Nations (Anishinaabe) perspectives on wellness. We engaged with Anishinaabe community members by using an iterative, collaborative Group Concept Mapping methodology to define strengths from a within-culture lens. Participants (n=13) shared what it means to live a good way of life/have wellness for Anishinaabe young adults, ranked/sorted their ideas, and shared their understanding of the map. Results were represented by nine clusters of wellness, which addressed aspects of self-care, self-determination, actualization, community connectedness, traditional knowledge, responsibility to family, compassionate respect towards others, enculturation, and connectedness with earth/ancestors. The clusters were interrelated; primarily in the relationship between self-care and focus on others. The results are interpreted by the authors and Anishinaabe community members though the use of the Seven Grandfather Teachings, which provide a framework for understanding Anishinaabe wellness. The Seven Grandfather Teachings include: Honesty (Gwayakwaadiziwin), Respect (Manaadendamowin), Humility (Dabaadendiziwin), Love (Zaagi’idiwin), Wisdom (Nibwaakaawin), Bravery/Courage (Aakode’ewin), and Truth (Debwewin).

Keywords: Wellness, First Nation, American Indian, Indigenous, Group Concept Mapping, Seven Grandfather Teachings

Introduction and Literature Review

Research on Indigenous peoples often focuses on negative behaviors and outcomes and neglects existing sources of strength and resilience (Hawkins, Cummins, & Marlatt, 2004; Sonn & Fisher, 1998). Thus, Indigenous communities consistently call for a positive reframing of health with emphasis on community strengths (Kirmayer, Dandeneau, Marshall, Phillips, & Williamson, 2011). As tribes exercise their sovereign right to govern decisions regarding research on tribal lands, and with the advancement of community-based participatory research practices in health sciences, Indigenous communities are increasingly involved in all aspects of the research process. Incorporating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives when conducting health research is one collaborative step that aims to honor core Indigenous values and beliefs (Brodsky, 2016; Fisher & Ball, 2003; Hartmann, Wendt, Saftner, Marcus & Momper, 2014).

Indigenous peoples have interacted with their environment in order to maintain health and wellbeing of community members and other living organisms since time immemorial. Positive psychology, or the study of “what is right” (Kobau et al., 2011), and the study of wellness may therefore be a useful intersect for Indigenous and community psychologies (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010, Schueller, 2009). Within the field of positive psychology, the concept of ‘wellness’ has been conceptualized in myriad ways to include factors such as mental wellness, well-being, positive functioning, satisfaction in life, engagement, and strengths (Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], 2009; Csikszentmihalyi, 1997; Duckworth, Steen, & Seligman, 2005; Keyes, 2002; Pavot & Diener, 2008; Seligman & Chikszentmihalyi, 2000; Seligman, 2012). Notably, the absence of disease does not equate to wellness, instead, positive dimensions of life must also be present (Duckworth et al., 2005; Keyes, 2002; WHO, 1948). Thus, general descriptions of wellness incorporate positive life domains encompassing emotional, physical, mental and social health.

Globally, Indigenous notions of wellness also focus on emotional, physical, mental and social health, yet move further to heavily emphasize interconnections and balance among mind, body, and spirit and between the individual, community, and the land (Cross et al., 2011; Lowe & Struthers, 2001; McCormick, 1996; 2009; Ullrich, 2019). Aspects of Indigenous wellness have included cultural and spiritual involvement (Hodge & Nandy, 2011; Kral, Idlout, Minore, Dyck, & Kirmayer, 2011; LaFromboise, Hoyt, Oliver, & Whitbeck , 2006), active participation in community (Boulton & Gifford, 2014), family and community support and sense of belonging (Hill, 2006; Hodge & Nandy, 2011; Kral et al., 2011 LaFromboise et al., 2006; Schultz et al., 2016a), the importance of the land and place (Goodkind, Gorman, Hess, Parker & Hough, 2015; Schultz, Walters, Beltran, Stroud & Johnson-Jennings, 2016b), and intergenerational/ancestral connection (Lowe & Struthers, 2001; Schultz et al., 2016a; Ullrich, 2019). Thus, individual, communal, and environmental wellness are interconnected.

Despite disproportionately high exposure to socio-historical stressors, levels of Indigenous adult positive mental health and psychological wellness have been found to be higher than, or on par with, that reported in other diverse, non-Native samples (Kading et al, 2015; Walls, Pearson, Kading & Teyra, 2016). Indigenous wellness has been linked to lower rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and suicidal ideation, and with greater feelings of connection to community, ability to speak tribal language, and engagement in tribal practices (Hodge & Nandy, 2011). Heightened levels of wellness in the face of adversity underscore the importance of learning about sources and meanings of wellness from Indigenous community perspectives. Thus, we set out to respond to calls for strengths-based, positive approaches to Indigenous research (Kirmayer et al., 2011) by incorporating Indigenous knowledge (Gone, 2016) and perspectives of wellness for Anishinaabe young adults. We collaborated with Anishinaabe community members using Group Concept Mapping (GCM) as a methodological tool to define strengths from a within-culture, detailed vantage point.

Community Settings and Involvement

The research team is represented by University and community-based members who have worked together on health research initiatives in the upper Midwestern US and Canada for nearly two decades. This project is supported by Tribal Government Resolutions (i.e., a formal document through which a tribal governing body expresses its will) from each of the participating tribal nations. Community collaborators include 34 members of Community Research Councils (CRCs) at each of eight reservations/reserves involved in the study. Members include young adults, elders, and local service providers, and all CRC representatives are Anishinaabe community members. To facilitate effective community-focused research, we established shared guidelines for open, respectful discussion and incorporated traditional Anishinaabe processes for sharing including offering tobacco to elders in the group and opening meetings with a traditional blessing. These guidelines are used in team meetings and members of CRCs are active partners in research design and focus, methodology, and implementation decisions, including review and contribution to manuscripts prior to publication. The project PI (MW) trained the CRCs in human participants’ safety and purposive sampling methods to recruit young adults from each reservation/reserve to participate in this community-based project. Training included written and verbal background information on the history of human safety and ethics violations in research, principles of the Belmont Report, and collaborative discussion about ethics in tribal research (e.g., community confidentiality, group-based research, historical exploitation of tribal communities by researchers, etc.). CRC members saw GCM as a participatory method that could be used to facilitate dialogue about what wellness meant for Anishinaabe young adults.

CRC members contributed substantively to the analysis and interpretation of results by defining the Seven Grandfather Teachings (discussed below) and identifying statements that aligned with the Teachings during a large-group meeting. This manuscript involves intensive collaboration among five authors: three of whom are Anishinaabe community members and researchers (MW, MG. JG) and two of whom are non-Native research collaborators (MK, KH). CRC input and these author backgrounds form the lens through which we approached the current work.

Methods

GCM is a unique participatory method of data collection that utilizes multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis (Kane & Trochim, 2007) and is useful for developing conceptual frameworks (Burke et al., 2005; Trochim, 1989). This method brings participants together to collectively brainstorm words or phrases in response to a focus statement, individually group the words/phrases into clusters, and individually rank each word/phrase and cluster. After analysis, participants interpret relationships between the clusters and word/phrases as a group (Burke et al., 2005; Kane & Trochim, 2007). The GCM methodology has been used with Indigenous communities (Busija et al, 2018; Dawson, Cargo, Steward, Chong & Daniel, 2013; Firestone, Smylie, Maracle, Siedule & O’Campo, 2014; Kading, 2015) and is a valuable approach to research collaboration due to its participatory nature (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). GCM is a structured method in which participants are the source of data as well as are integral to the analysis of data and interpretation of the results. GCM is also similar to the Indigenous method of “Research Talking Circles,” that gain and share knowledge through discussion in a setting where all participants are considered equal and may experience transformation through the process of sharing (Graveline, 2000; Lavallee, 2009; Wilson, 2001).

On par with GCM sample size recommendations (minimum: 10–12; Jackson & Trochim, 2002) the CRCs recruited 13 participants (total n = 13) from on or near their reservation/reserve communities for this GCM project, which took place from November to December 2016. The inclusion criteria were adults aged 19–29 years who self-identified as Anishinaabe. Participants were encouraged, but not required, to participate in every step of GCM. They received $20 USD at the completion of steps 1 and 2, and an additional $20 USD at the completion of step 3. Step 3 in-person meetings were held in two regional locations for which participants received travel reimbursement and childcare.

At step 1, each participant was given a unique username and password to brainstorm and enter their responses online to the focus prompt “An Ojibwe/Anishinaabe young adult is living a good way of life (has wellness in their life) when they…”. Participants completed this individually at their own pace and were invited to share as many ideas as possible. This process generated a total of 163 statements. The GCM facilitator (MK) combined or reduced statements that were identical for 97 final statements, and this consolidation was reviewed by (MW).

For step 2 (also completed online by individuals at their own pace), each participant grouped the 97 statements according to their similarity (Coxon, 1999; Kane & Trochim, 2007; Rosenberg & Kim, 1975; Weller & Romney, 1988). Participants also individually ranked statements according to the prompt: “Rank each statement based on the degree of impact you feel it has on an Ojibwe/Anishinaabe young adult living a good way of life.” The ranking of “1” indicated “least degree of impact” and “5” indicated “greatest degree of impact.” Participants were encouraged to use the full range of the scale when ranking the list.

Next, the GCM facilitator used Concept Systems Global MAX software (The Concept System Global MAX, 2016) to analyze the participant-driven ranking and sorting data by: 1. Creating a similarity matrix representing the number of times each pair of statements was sorted together, 2. Using multidimensional sorting to create a two-dimensional map of points representing unique statements (Davison, 1983; Kruskal & Wish, 1978), and 3. Using hierarchical cluster analysis with Ward’s algorithm to divide the coordinates into clusters (Everitt, 1980). The facilitator also generated mean ranking values for each item and cluster based on participants’ individual rankings and conducted t-tests to test for significant differences in mean ranking between clusters. The result of these analyses produced a visual concept map representing the focus statement: a good way of life (wellness in life) for an Ojibwe/Anishinaabe young adult. Because all brainstorming data and sorting and ranking information was participant generated, the result of the analysis (the concept map) reflected how the participants as a whole grouped and ranked the brainstormed statements that represented a good way of life.

Step 3 was held in-person in two regional locations (i.e., two separate groups) during which participants interpreted the maps in audio-recorded sessions. Participants shared interpretations of the content clusters in the form of titles, representative statements, or phrases. They also shared their interpretations of the overall content of the map, the rankings of each cluster, and the potential utility of the results. Participant quotes from the meeting transcripts are incorporated into the manuscript to include Anishinaabe perspectives in the presentation and interpretation of results. In addition, CRC and author interpretation of results vis-à-vis Anishinaabe cultural values is reflected in the discussion section of this manuscript.

In summary, the entire GCM facilitation, analysis, and interpretation process involved the following: 1) Step 1—Participants brainstormed statements in response to the focus prompt, 2) Step 2—Participants sorted and ranked the brainstormed statements, 3) Analysis—The facilitator analyzed the participant-driven ranking and sorting data with GCM software to produce the concept map, 4) Step 3—Participants interpreted the concept map, and 5) Interpretation—The CRC defined the Seven Grandfather Teachings (discussed below) and identified statements that aligned with the Teachings.

Results

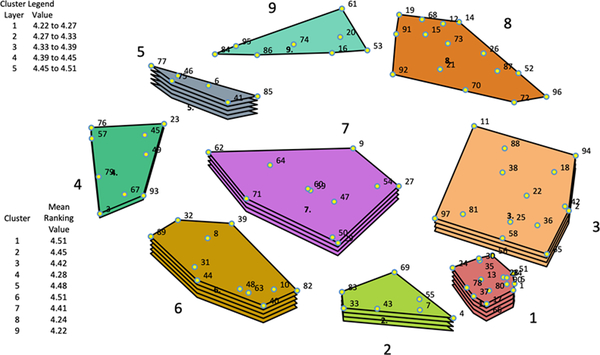

The 97 brainstormed items (Table 1) were sorted into a concept map with nine clusters (Figure 1). Participants from both groups gave each cluster a title (i.e. two titles were selected—one from each group of participants) and both titles have been retained in order to acknowledge the contribution of all participants during step 3.

Table 1.

Final Statements by Cluster

| Cluster Number | Cluster Title | Statements |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | My wellness wheel/Taking care of themselves (mind, body, spirit); Self-Care | 1. Laugh 5. Take care of themselves (mind, body, spirit) 13. Take pride in themselves and who they are 17. Are alcohol free 24. Stay focused and keep on the right track in life 28. Overcome obstacles in life 30. Give back to themselves 34. Rest 35. Have self awareness 37. Are drug free 51. Take care of emotional, spiritual, physical, mental well-being 56. Are who they are (true to themselves 100%) 66. Don’t abuse their body (with drugs, alcohol, etc.) 78. Walk the Red Road of Sobriety 80. Love life 90. Are in control of their own lives |

| 2 | Taking care of oneself (physically); Self determination | 4. Accept their own “flaws” (the things some might see as flaws, and others might not) 7. Are positive 33. Take care of their finances (invest, save money, etc.) 43. Look forward to their future 55. Live life to the fullest 69. Set/Have goals 83. Follow through/work towards goals (don’t give up) |

| 3 | What an Elder would tell me (respect towards self); Selfacceptance | 2. Are proud of being Anishinaabe despite stereotypes and racism 11. Are proud of where they came from 18. Life their life with mini-bimaatiziwin (a good life) in mind. 22. Acknowledge/know where they came from, as it helps guide where they are going in life 25. Live each day with integrity 36. Are free from hate 38. Pursue and further their education 42. Learn from their experiences and “mistakes” (it all has meaning) 58. Respect themselves 65. Do self-work 81. Are forgiving 88. Accept the knowledge/teaching(s) they receive from themselves 94. Acknowledge their past, but don’t dwell on what has happened or what people have said 97. Are responsible (not careless) |

| 4 | Steps to becoming a leader; Obligation to the community | 3. Have mentors around them 23. Teach the younger generations what they know 45. Fight for the people 49. Pay attention to the societal and ethical implications of actions and consumer choices 57. Attend community events—Ojibwe or not 67. Take care of those who can’t care for themselves 76. Take action when things are not going okay in their communities (going to meetings, voicing concerns, etc.) 79. Help/give back to their community 93. Help others |

| 5 | Elder’s teachings (Respect toward elders); Share and seek knowledge | 6. Listen and help one another in order to move forward the betterment of all nations 41. Know that knowledge keeping is meant to be shared, not to be used selfishly 46. Honor the elders 75. Give back to the elders 77. Listen to knowledge keepers 85. Respect (If they want respect, they must give respect) |

| 6 | Family/Working to provide for family; Family relationships | 8. Work on creating and maintaining healthy relationships 10. Promote family values 34. Give back to the family/spouse/children who have affected their life in a positive way 35. Take care of loved ones 39. Are role models (personally and professionally) 40. Promote (positive) work ethics 44. Practice and be the best parent they can be 48. Step up to the plate as a father 63. Take care of their children, even if that means doing it alone 82. Work hard for what they want in life 89. Focus on the kind of grandparent or elder they want to be |

| 7 | Sensitive towards others; Open minded & respect | 9. Do acts of kindness 27. Accept that they cannot change people, but can help them to understand others 29. Stand up for what they believe in 47. Approach situations with care 50. Are open minded 54. Approach situations with love 59. Approach situations with peace 60. Approach situations with compassion 62. Respect others (Elders as well as parents, siblings, coworkers, boss, friends, neighbors) 64. Don’t shame others for living differently 71. Are generous/give freely to those around them |

| 8 | Being Anishinaabe; Culture | 12. Know/Learn and use the Ojibwe language 14. Can learn their culture and traditions 15. Know/practice (try to understand) their Anishinaabe culture and traditions 19. Learn about their ancestors 21. Involve the Medicine Wheel/culture, traditions, and medicines into everyday life (smudge sage, tobacco, etc.) 26. Take the time to learn the seven grandfather teachings throughout their life 52. Live the good life (try to live with seven grandfather teachings and culture as well as western way of living—both lives in harmony 68. Participates in ceremonies (shaking tent, full moon ceremony, pow wows, sweat lodge, etc.) 70. Respect all creation 72. Recognize the interconnectedness of their spiritual, emotional, and physical health 73. Always follow the seven grandfather teachings in everything they do 87. Reflect on the histories of their people in order to understand their current circumstances 91. They keep the culture and traditions alive 92. Teach little ones the seven teachings 96. Have a connection with the creator |

| 9 | Knowledge/learning and the connection with the land/earth, past, present; Honor the earth/ancestors | 16. Ask advice from elders/listen to the advice of elders 20. Live to honor the sacrifices of their ancestors 53. Listen to what they are being taught by the earth around them 61. Cultivate a connection with the soil and seeds that provide them with life 74. Stay connected to family roots and pass on to younger generations 84. Never take more than what is needed 86. Are protectors of the land/take care of/respect/honor mother earth 95. Teach/help others learn culture, values, wellness |

Figure 1: Concept Map.

Statements (points) situated close to each other on the map (e.g. #14 and #91) were sorted together more often by participants, indicating their similarity. Items situated further from each other on the map (e.g. #14 and #44) were sorted together less often or never, indicating their dissimilarity. Relative distance between points is meaningful, while orientation (top, bottom, center, etc.) is not. The nine clusters are identified. The mean ranking value of each cluster is depicted by the number of layers shown: a greater number of layers indicates a higher mean ranking value. Higher mean ranking values are associated with the cluster being perceived by participants as having a higher level of impact on living a good way of life. We found some statistically significant differences in rankings between clusters, though effect sizes were comparable.

We present the contents of each cluster, group-selected cluster titles, participant interpretation, and their relation to previous wellness research below.

Cluster 1: My Wellness Wheel/Taking Care of Themselves (Mind, Body, Spirit); Self-Care

Aspects of self-care including staying drug and alcohol free, being self-aware and in control of one’s life are represented in Cluster 1 statements. This cluster was ranked (see Figure 1) as having a greater impact on a young adult living a good way of life than several other clusters. Participants considered personal care essential to achieving other aspects of wellness: “Yeah, you know, I’m glad all of us think [cluster] number 1 should be [ranked] number 1 because, I mean, a lot of people don’t see that where in order to take care of yourself, you can’t take care of anybody else [before yourself].” Self-care has been previously recognized in both non-Indigenous and Indigenous communities as a necessary component of holistic wellness (Cross et al. 2011; Gowen, Bandurrage, Jivanjee, Cross, & Friesen, 2012; Hodge & Nandy, 2011) and this cluster highlights aspects of mind, body, and spirit in self-care.

Cluster 2: Taking Care of Oneself (Physically); Self-Determination

Self-determination, an important component of psychological wellness (Ryan & Deci, 2000), was represented by the content (take care of their own finances, set/have goals, follow through/work towards goals, etc.) and interpretation of Cluster 2. When naming Cluster 2, one woman commented on the title choice, “That’s a good one [self-determination] because I had, like, personal responsibility [written down] but I just meant, you being responsible, taking care of the things that you need to take care of. I like determination [as a title] better.” Cluster 2 was also defined as taking care of oneself physically, which is in line with previous Indigenous wellness notions (Hodge & Nandy, 2011). One woman reported, “I find these [statements] are more, like, physical stuff… like, the goals, and then the money, and [accept] their own flaws.” Overall, participants highlighted the importance of being able to set and accomplish goals and look to the future.

Cluster 3: What an Elder Would Tell Me (Respect Towards Self); Self-Acceptance

Cluster 3 was interpreted as being able to accept or respect self and included components of actualization. Actualization has been defined in Indigenous identity contexts as integrating the “best of both worlds” (i.e. traditional and dominant culture) and the adoption of healthy psychological buffers in order to combat further internalization of colonizing attitudes (pp. 173; Walters, 1999). Identity and ethnic pride are essential to the foundation of wellness (Priest, Mackean, Davis, Briggs & Walters, 2012) and such actualization can mitigate negative effects of discrimination on wellness (Martinez & Dukes, 1997). One woman shared, “acknowledging where you come from, being proud of who you are, … [the statement] ‘are forgiving…’ that’s, you know, accepting your circumstances.” These ideas represent the heart of this cluster: pride in being Anishinaabe despite stereotypes, respecting self, and acknowledging the past without dwelling on it.

Cluster 4: Steps to Becoming a Leader; Obligation to the Community

Cluster 4 represents multiple levels of community connectedness. Items within the cluster (i.e.: teach the younger generations; have mentors around them; take action when things are not going okay in their communities; pay attention to the societal and ethical implications of actions and consumer choices) emphasize the responsibility an individual has to youth, mentors, community, and society. One woman expressed the need to “help or give back, like take action in your community, take care of other people, attend community events, pay attention to your societal implications, pray for the people.” Similarly, other researchers document the importance of having connection to an extended social network, not merely to receive social support, but to give support to others; active participation in extended relationships gives individuals purpose and shapes one’s identity (Boulton & Gifford, 2014; Cross et al., 2011). Notably, one participant in Priest et al. (2012) stated that it was impossible to disconnect from community because that would mean disconnecting from yourself that, “in order to stay well, you need that connectedness” (p. 185).

Cluster 5: Elder’s Teachings (Respect Toward Elders); Share and Seek Knowledge

Cluster 5 represents traditional knowledge by addressing the act of acquiring knowledge, the use of knowledge acquired, and the position of “knowledge keepers”. In a dialogue between two participants the following information is shared:

Female 1: “…understanding that knowledge is a…”

Female 2: “…Cycle?”

Female 1: “Yeah, like, you learn from people, and people learn from you and it’s important to…listen and help one another to move forward and knowledge is meant to be shared, and listen to people with knowledge”.

Gone (2012) alludes to the cyclical nature of Indigenous traditional knowledge in that it is only within personal or first-hand experience of a knowledge keeper that his/her knowledge is validated. This approach to learning is based in listening to and honoring the ones that have many years of personal experience—the elders. In similar ways to Cluster 4, knowledge is returned to the community by the sharing of knowledge and giving back to elders—the knowledge keepers. This focus on knowledge expands our understanding of what wellness means for Anishinaabe young adults: that it includes seeking and sharing knowledge, not just having social support/good relationships, as emphasized in previous research (Peterson, 2006; Seligman, 2012; Vaillant, 2003).

Cluster 6: Family/Working to Provide for Family; Family Relationships

Cluster 6 contains statements related to responsibility to family. Various aspects of social support and interpersonal relationships are included in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous wellness literature (Peterson, 2006; Richmond, Ross, & Bernier, 2007; Seligman, 2012; Vaillant, 2003; Whitbeck, Hartshorn, & Walls, 2014). In response to this cluster, one participant agreed, “Yeah. Anything about family, family relationships. I kept thinking of the word, ‘responsibility.’ I want to put that in like every single one [of the cluster titles].” Social support from close family and friend networks is predictive of wellness among Indigenous peoples, even in the face of adversity (Richmond et al., 2007). Family wellness, more specifically, has been identified as a central influence of individual health (Boulton & Gifford, 2014). Notably, this cluster goes beyond the benefit gained from having family relationships and networks, and focuses on a person’s responsibility to care for family.

Cluster 7: Sensitive Towards Others; Open Minded & Respect

The statement list and discussions around Cluster 7 centered around acts and intentions of kindness towards others, as well as a sense of compassionate respect. As one female participant stated, “I feel like this is all about how you treat other people.” Participants articulated a specific focus on open-mindedness, acceptance, and generosity towards other humans that in some ways reflects communal orientation and relational wellness (e.g., Cross, 1998) but also moves beyond previously documented conceptions of wellness by centering one’s own wellness in how we approach and behave towards others.

Cluster 8: Being Anishinaabe; Culture

While several of the clusters included statements about or related to Anishinaabe culture, Cluster 8 most specifically and directly evoked enculturation, represented by Anishinaabe teachings, traditions, and values. Cultural values likewise permeate other Indigenous-specific explanations of wellness (Cross 1997; Hodge & Nandy, 2011; Kading, 2015; Kading et al, 2015; Kirmayer et al., 2011), and cultural involvement and reclamation has been linked to a variety of positive health outcomes in diverse Indigenous communities (Kading et al, 2015; Stone, Whitbeck, Chen, Johnson, & Olson, 2006; Schiefer & Krahé, 2014). Notably, the statements in this cluster offer insight into dimensions of culture considered necessary for wellbeing (e.g., learning cultural ways, engaging with ceremony, teaching young ones, living the values). In all, the statements generated in Cluster 8 highlight active, purposeful engagement to learn, practice, and share Anishinaabe cultural values and activities.

Cluster 9: Knowledge/Learning and the Connection with the Land/Earth, Past, Present; Honor the Earth/Ancestors

GCM group meeting participants viewed statements about honoring ancestors AND the earth as intertwined; as one female participant noted, “to honor the sacrifices of their ancestors…you do that by taking care of the earth, you know what I mean?” Another woman noted, “yeah, and, and your ancestors, like, they become that soil, that grows, that plant, you know, the seeds, you know, so that is the earth, like, if you’re going to honor your ancestors.” Research with Alaska Native communities has similarly identified an “awareness of connectedness,” (see also Cluster 4) which encompasses an individual’s sense of connectedness in relation to their self, family, community, and the natural environment (Mohatt, Fok, Burket, Henry, & Allen, 2011). Other researchers confirm that connectedness is positively associated with wellness behaviors and wellness among AI/AN peoples (Hazel & Mohatt, 2001).

Mean Ranking Analysis of Clusters in the Concept Map

Results of the mean ranking analysis revealed that each of the nine clusters were ranked as having a relatively high level of impact on living a good way of life (Figure 1). Clusters were approximately evenly ranked vis-à-vis one another, though some numeric differences did reach statistical significance.

Culture and spirituality are often prioritized in Indigenous wellness research based on the assumption that these critical aspects of culture can lead to wellness (Hodge & Nandy, 2011; Kral et al., 2011; Priest et al., 2012). This may be why some participants expressed surprise that they had ranked Cluster 8, which was focused on Anishinaabe teachings, traditions, and values, as slightly lower than clusters focused on self (Clusters 1, 2, 3; note the number of layers beneath each of these clusters in Figure 1). However, other participants reasoned that some basic aspects of caring for self are essential in order to follow traditional teachings, traditions, and values. One woman commented, “Yeah, but, but, the personal care things, I mean like not abusing alcohol and, you know, that’s very, very basic, like you need that or you’re, you know, you’re going to suffer.” Another woman agreed, “Yeah, you can’t get to [Cluster] 8 unless you do [Clusters] 1 through 3, you know.” Participants commented that, in some respect, an individual had the ability to better focus on Anishinaabe teachings, traditions, and values if they could first address their own self-care needs and that self-care was a necessary precursor to achieving the remaining aspects of wellness, similar to other Indigenous frameworks that place the wellbeing of the individual at the center of the model (Priest et al., 2012; Ullrich, 2019). Despite the slight differences in mean ranking values between clusters, participants felt that each of the individual clusters and particularly the concept map as a whole represented a meaningful depiction of what it means for an Anishinaabe young adult to live a good way of life/have wellness.

Discussion: Interconnectedness of Clusters and the Seven Grandfather Teachings

The theme of interconnectedness and balance is integral to many Indigenous notions of wellness (Cross, 1998; Lowe & Struthers, 2001; McCormick, 2009) and inspires consideration of the clusters individually and collectively. While each cluster depicts a specific domain of what it means for an Indigenous young adult to live a good way of life/have wellness, the clusters are highly interconnected.

An indicator of connectivity across the map is the presence of similar indicators of wellness emerging in multiple clusters (e.g., self-care [Clusters 1, 2, 3], connection [Clusters 4 and 9], sharing of knowledge [Cluster 3 and 5], etc.). In particular, statements representing aspects of the Seven Grandfather Teachings—values and beliefs commonly used within Ojibwe/Anishinaabe communities—appear in multiple clusters across the map. The exact definition of the Seven Grandfather Teachings varies slightly across Anishinaabe people and communities, and the Teachings referenced in this manuscript are those as defined by the CRC members, elders, and the Anishinaabe authors on our collaborative research team (see acknowledgements). Several of the Teachings were explicitly named in the brainstorming process, and are reflected in statements #26, 52, 73, and 92. In dialogue during the interpretation session (Step 3), participants commented on the relevance of the Teachings to the overall content of the map:

Female 1: Do you think a lot of these fit into the, into the Teachings?

Female 2: Yeah, I mean. It just makes sense that people would, that these are the things that people would list as important.

Facilitator: Do you think that, like, the Teachings would be related to wellness, kind of like, would that be a fair thing to say?

Female 2: I think that’s what they are for, kind of.

The Teachings represent a unifying framework for considering Anishinaabe notions of wellness and CRC members and authors viewed the Teachings as a valuable lens through which to understand the results. The Teachings include Honesty (Gwayakwaadiziwin), Respect (Manaadendamowin), Humility (Dabaadendiziwin), Love (Zaagi’idiwin), Wisdom (Nibwaakaawin), Bravery/Courage (Aakode’ewin), and Truth (Debwewin). The underlying messages of the Teachings permeated the map even beyond explicit naming of specific values, and some statements reflected multiple Teachings. The CRCs reviewed the concept map and identified numerous brainstormed statements (quoted in the following paragraphs) as reflecting the Teachings.

For example, Honesty (Gwayakwaadiziwin) is reflected in statements “do self-work,” “acknowledge their past, but don’t dwell on what has happened or what people have said,” and “promote (positive) work ethics.” These statements imply that one must be honest with oneself in order to demonstrate honesty in practice.

Respect (Manaadendamowin) is reflected in statements “take care of themselves (mind, body, spirit),” “work on creating and maintaining healthy relationships,” “help/give back to their community,” and “pay attention to societal and ethical implications of actions and consumer choices.” Statements categorized for Respect indicate multiple levels of responsibility to respect oneself, family, community, and the larger society.

Humility (Dabaadendiziwin) is reflected in such statements as “learn from their experiences and ‘mistakes’,” “are forgiving,” and “listen to knowledge keepers.” These statements allude to being able to forgive oneself, especially when mistakes are made, and the ability to be open to listening and learning from others.

Love (Zaagi’idiwin) requires one to “take care of themselves” and “do self-work.” Love also implies pride in oneself amidst the negativity of others, indicative in statements like “are proud of being Anishinaabe despite stereotypes and racism.” Finally, Love requires action: “give back to the elders” and “take care of loved ones.”

Wisdom (Nibwaakaawin) was reflected in statements of learning and teaching: “accept the knowledge/teaching(s) they receive from themselves,” “learn their culture and traditions,” and “teach the younger generation what they know.” Wisdom was also reflected in practicing the teachings they acquired: “have mentors around them,” “are role models (personally and professionally),” and “participate in ceremonies.” According to these statements, Wisdom required much more than retaining knowledge; Wisdom implies knowing, giving, and practicing the teachings.

Bravery (Aakode’ewin) was implied in statements around perseverance: “overcome obstacles in life” and “walk the red road of sobriety.” Bravery was also reflected in statements around parenthood: “step up to the plate as a father” and “take care of their children, even if that means doing it alone”; indicating that Bravery meant taking on challenging roles and responsibility for family. In addition, Bravery statements included “fight for the people” and “take action when things are not going okay in their communities (going to meetings, voicing concerns, etc.).” These statements indicate a responsibility to take necessary action for the betterment of the community.

Truth (Debwewin) was reflected in statements “live their life with mino-bimaadiziwin (a good life) in mind,” “always follow the seven grandfather teachings in everything they do,” “have a connection to the Creator,” and “teach/help others learn culture, values, and wellness.” These statements imply Truth has a spiritual and cultural grounding. Living with Truth meant living by all other Teachings.

The Teachings are an important guiding framework for wellness research in Anishinaabe communities. Respected Elder from Red Lake, MN, the late Larry Stillday noted, “the Seven Grandfather Teachings are gifts or blueprints for living a good life. Each Teaching is a gift of knowledge for the learning of values and living by those values” (personal communication, February, 2014). While not used in all Anishinaabe communities, the Teachings are commonly taught to guide positive wellness behaviors and the results of the concept map aligned with many of the Teachings. For example, wisdom was exemplified by statements about sharing and receiving knowledge, bravery-related statements included physical, emotional, and social courage, and love was represented by statements about self-love as well as love towards others. To our knowledge, previous literature has not explicitly linked the Teachings to Anishinaabe wellness. This participatory research contributes to an understanding of wellness in Anishinaabe young adults by defining wellness as a balance between spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental health that is guided by the underlying values of the Teachings. While the explicit inclusion of the Teachings in considering Anishinaabe wellness is a novel concept for researchers, the importance of culture in Indigenous wellness is not, as noted by a participant in Priest, et al. (2012), “When people say wellbeing to me, all I need is culture because within that is everything you’ll find anywhere else” (p.184).

Future Directions & Limitations

The entire research team (University and community-based members, including the CRCs) selected the GCM project and facilitator, a trusted collaborator and one of the non-Native authors on this paper. It is important to consider that the GCM facilitator’s lived experience is not one of an Indigenous person and as such, facilitation of the project and participant reaction was influenced by the GCM facilitator’s background.

The results of the concept map, in combination with the values of the Teachings, represent Anishinaabe community strengths. While achieving wellness is facilitated within Indigenous communities by rich embedded cultural strengths (e.g. the Teachings), it is important to note that there are deep historical and contemporary barriers to achieving wellness (i.e. cultural oppression and historical trauma; Evans-Campbell, 2008; Stannard, 1992; Thornton, 1987; Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen & Stubben, 2001; Whitbeck, McMorris, Hoyt, Stubben & LaFromboise, 2002; Roubideaux, 2005). The impact of these barriers on wellness should not be ignored and is worthy of future research. For example, one participant commented on the difficulty of living in “two worlds:”

“Yeah, I think an important question to ask is, like, for the culture one [Cluster 8] and the accepting yourself one [Cluster 3], you know, asking a question like, ‘how many times do you feel like your culture is like in conflict with something?’ …Like, how many times do you feel like something is um, like, conflicting, conflicting with your cultural values or, do you know what I mean? Cause, like, uh, I think that’s important, that’s an important part of wellness, like, you know, one of the things was accepting who you are, accepting where you come from, but then if you are walking around in your daily life you are getting bombarded with, like, you know, hate or whatever it might be, that’s definitely going to impact your wellness, but I think that’s kind of an important question, like, how often is, you know, how often do you find that, like, attention there?”

Indigenous young adults may experience a cultural predicament: though enculturation is widely considered a protective mechanism, complex issues of fragmented communities and postcolonial realities (e.g. historical trauma) may result in some individuals and communities having difficulty accessing cultural strengths (Kirmayer, Gone, & Moses, 2014). Thus, future research should focus on further exploring the nuances of the effects of colonization on achieving wellness as well as further elucidate sources and meanings of wellness from Indigenous community perspectives.

Conclusion

This study responds to calls for strengths-based research with Indigenous communities and describes an Indigenous framework for wellness from the perspectives of Anishinaabe young adults. We utilized GCM techniques to better understand Anishinaabe perspectives on wellness/living a good way of life. The results suggest that wellness for Anishinaabe young adults consists not only of physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental health, as has been suggested in previous research, but also incorporates and is framed by the Seven Grandfather Teachings. This can be seen as the reflection of a balance and interconnectedness between elements of Anishinaabe wellness and may represent an essential component to health and wellness promotion efforts in Anishinaabe communities.

Acknowledgements

Community Research Council (CRC) Members: Laura Bruyere, David Bruyere, Annabelle Jourdain, Priscilla Simard, Shailyn Loyie, Howard Kabestra, Dallas Medicine, Glenn Cameron, Gerilyn Fisher, Gabe Henry, Frances Whitfield, Tina Handeland, GayeAnn Allen, Victoria Soulier, Clinton Isham, Betty Jo Graveen, Carol Jenkins, Gloria Mellado, Bill Butcher Jr., Delores Fairbanks, Bernadette Gotchie, Jim Bedeau, Devin Fineday, Kathy Dudley, Geraldine Brun, June Holstein, Ed Strong, Frannie Miller, Murphy Thomas, Brenna Pemberton, Cindy McDougall, Stephanie Williams, Celeste Cloud, Pat Moran, Laurie Vilas, and Whitney Accobee.

Rowan Simonet, for editing and formatting assistance.

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DA039912 (M. Walls, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We have followed APA principles regarding treatment of participants in our research. Our research was approved by our Community Research Councils, the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board and by each participating tribal nation via Tribal Government Resolutions.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Boulton AF, & Gifford HH (2014). Whanau ora; He whakaaro a whanau: Maori family views of family wellbeing. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 5(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky AE (2016). Taking a stand: The next 50 years of community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 284–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell DA, & Trochim WM (2005). An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qualitative Health Research, 15(10), 1392–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busija L, Cinelli R, Toombs MR, Easton C, Hamptom R, Holdsworth K, … McCabe MP (2018). The role of elders in the wellbeing of a contemporary Australian indigenous community. The Gerontologist, 19(2), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2009). Improving the health of Canadians: Exploring positive mental health. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information. [Google Scholar]

- Coxon APM (1999). Sorting data: Collection and analysis (Vol. 127). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL (1998). Understanding family resiliency from a relational world view In McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, & Fromer JE (Eds.), Resiliency in Native American and immigrant families 2, 143–157. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL (1997). Understanding the relational worldview in Indian families [Part 1]. Pathways Practice Digest, 12(4), 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL, Friesen BJ, Jivanjee P, Gowan LK, Bandurraga A, Matthew C, & Maher N (2011). Defining youth success using culturally appropriate community-based participatory research methods. Best Practices in Mental Health, 7(1), 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Davison ML (1983). Multidimensional scaling. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson AP, Cargo M, Steward H, Chong A, & Daniel M (2013). Identifying multi-level culturally appropriate smoking cessation strategies for Aboriginal health staff: A concept mapping approach. Health Education Research, 28(1), 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Steen TA, & Seligman MEP (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt B (1980). Cluster analysis. Quality and Quantity, 14(1), 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone M, Smylie J, Maracle S, Siedule C, & O’Campo P (2014). Concept mapping: Application of a community-based methodology in three urban Aboriginal populations. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 38, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, & Ball TJ (2003). Tribal participatory research: Mechanisms of a collaborative model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3–4), 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP (2016). Alternative knowledges and the future of community psychology: Provocations from an American Indian healing tradition. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP (2012). Indigenous traditional knowledge and substance abuse treatment outcomes: The problem of efficacy evaluation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gorman B, Hess JM, Parker DP, & Hough RL (2015). Reconsidering culturally competent approaches to American Indian healing and well-being. Qualitative Health Research, 25(4), 486–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LK, Bandurrage A, Jivanjee P, Cross T, and Friesen B (2012). Development, testing, and use of a valid and reliable assessment tool for Urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth programming using culturally appropriate methodologies. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 21(2), 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Graveline FJ (2000). Circle as methodology: Enacting an Aboriginal paradigm. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 13(4), 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann WE, Wendt DC, Saftner MA, Marcus J, & Momper SL (2014). Advancing community-based research with urban American Indian populations: Multidisciplinary perspectives. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, & Marlatt GA (2004). Preventing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 304–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel KL, & Mohatt GV (2001). Cultural and spiritual coping in sobriety: Informing substance abuse prevention for Alaska Native communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 29(5), 541–562. [Google Scholar]

- Hill DL (2006). Sense of belonging as connectedness, American Indian worldview, and mental health. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20(5), 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge FS, & Nandy K (2011). Predictors of wellness and American Indians. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(3), 791–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, & Trochim WMK (2002). Concept mapping as an alternative approach for the analysis of open-ended survey responses. Organizational Research Methods, 5(4), 307–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kading ML (2015). Positive mental health: A concept mapping exploration (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. http://hdl.handle.net/11299/175200.

- Kading ML, Hautala DS, Palombi LC, Aronson BD, Smith RC, & Walls ML (2015). Flourishing: American Indian positive mental health. Society and Mental Health, 5(3), 203–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M, & Trochim WMK (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Research, 43(2), 207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, & Williamson KJ (2011). Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(2), 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Gone JP, & Moses J (2014). Rethinking historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(3), 299–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobau R, Seligman MEP, Peterson C, Diener E, Zack MM, Chapman D, & Thompson W (2011). Mental health promotion in public health: Perspectives and strategies from positive psychology. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral MJ, Idlout L, Minore JB, Dyck RJ, & Kirmayer LJ (2011). Unikkaartuit: Meanings of well-being, unhappiness, health, and community change among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3–4), 426–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal JB, & Wish M (1978). Multidimensional scaling. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Hoyt DR, Oliver L, & Whitbeck LB (2006). Family, community, and school influences on resilience among American Indian adolescents in the upper midwest. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(8), 975–991. [Google Scholar]

- Lavallee LF (2009). Practical application of an Indigenous research framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and Anishinaabe symbol-based reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, & Struthers R (2001). A conceptual framework of nursing in native American culture. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(3), 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez RO, & Dukes RL (1997). The effects of ethnic identity, ethnicity, and gender on adolescent well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26(5), 503–515. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick R (2009). Aboriginal approaches to counseling In Kirmayer LJ & Valaskakis GG (Eds.), Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada, (337–354). Vancouver, BC: UBC press. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick R (1996). Culturally appropriate means and ends of counselling as described by the First Nations people of British Columbia. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 18(3), 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M & Wallerstein N (2003). Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt NV, Fok CCT, Burket R, Henry D, & Allen J (2011). Assessment of awareness of connectedness as a culturally-based protective factor for Alaska Native youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(4), 444–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson GB, & Prilleltensky I (2010). Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, & Diener E (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C (2006). A primer in positive psychology. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Mackean T, Davis E, Briggs L, & Waters E (2012). Aboriginal perspectives of child health and wellbeing in an urban setting: Developing a conceptual framework. Health Sociology Review, 21(2), 180–195. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond CAM, Ross NA, & Bernier J (2007). Exploring Indigenous concepts of health: The dimensions of Métis and Inuit health. Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi), 4, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, & Kim MP (1975). The method of sorting as a data-gathering procedure in multivariate research. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 10(4), 489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubideaux Y (2005). Beyond Red Lake: The persistent crisis in American Indian health care. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(18), 1881–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefer D, & Krahé B (2014). Ethnic identity and orientation to White American culture are linked to well-being among American Indians–But in different ways. Social Psychology, 45(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schueller SM (2009). Promoting wellness: Integrating community and positive psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(7), 922–937. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz K, Cattaneo LB, Sabina C, Brunner L, Jackson S, & Serrata JV (2016a). Key roles of community connectedness in healing from trauma. Psychology of Violence, 6(1), 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz K, Walters KL, Beltran R, Stroud S, & Johnson-Jennings M (2016b). “I’m stronger than I thought”: Native women reconnecting to body, health, and place. Health and Place, 40, 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York; Toronto: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, & Csikszentmihalyi M (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonn CC, & Fisher AT (1998). Sense of community: Community resilient responses to oppression and change. Journal of Community Psychology, 26(5), 457–472. [Google Scholar]

- Stannard DE (1992). American holocaust: The conquest of the New World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stone RAT, Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Johnson K, & Olson DM (2006). Traditional practices, traditional spirituality, and alcohol cessation among American Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(2), 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Concept System® Global MAXTM (Built 2016.046.12) [Web-based Platform]. (2016). Ithaca, NY: Available from http://www.conceptsystemsglobal.com. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton R (1987). American Indian holocaust and survival: A population history since 1492. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim WMK (1989). Concept mapping: Soft science or hard art? Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(1), 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich JS (2019). For the love of our children: An Indigenous connectedness framework. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE (2003). Mental health. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1373–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls M, Pearson C, Kading M, & Teyra C (2016). Psychological wellbeing in the face of adversity among American Indians: Preliminary evidence of a new population health paradox? Annals of Public Health and Research, 3(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K (1999). Urban American Indian identity attitudes and acculturation styles. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 2(1–2), 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC, & Romney AK (1988). Systematic data collection. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hartshorn KJ, & Walls ML (2014). Indigenous adolescent development: Psychological, social and historical contexts. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, McMorris BJ, Chen X, & Stubben JD (2001). Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(4), 405–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, McMorris BJ, Hoyt DR, Stubben JD, & LaFromboise T (2002). Perceived discrimination, traditional practices, and depressive symptoms among American Indians in the Upper Midwest. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(4), 400–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S (2001). What is indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1948). Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19–22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.