Abstract

Introduction:

6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TG), two anticancer drugs, have high systemic toxicity due to a lack of target specificity. Therefore, increase target selectivity should be right increase drug safety.

Areas covered:

The authors examine the hypothesis that new prodrug designs based upon mechanisms of kidney-selective toxicity of trichloroethylene would reduce systemic toxicity and improve selectivity to kidney and tumor cells. Two approaches specifically were investigated. The first approach was based upon bioactivation of trichloroethylene-cysteine S-conjugate by renal cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases. The prodrugs obtained were kidney-selective but exhibited low turnover rates. The second approach was based on the toxic mechanism of trichloroethylene-cysteine S-conjugate sulfoxide, a Michael acceptor that undergoes rapid addition-elimination reactions with biological thiols.

Expert opinion:

Glutathione-dependent Michael addition-elimination reactions appear to be an excellent strategy to design highly efficient anticancer drugs. Targeting glutathione could be a promising approach for the development of anticancer prodrugs because cancer cells usually upregulate glutathione biosynthesis and/or glutathione S-transferases expression.

Keywords: 6-mercaptopurine, 6-thioguanine, anticancer prodrug design, bioactivation, cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases, glutathione, Michael addition, tumor cell-selective prodrug, trichloroethylene

1. Introduction

Prodrugs are derivatives of drug molecules that can be enzymatically and/or non-enzymatically transformed into the active parent drugs in vivo [1–7]. The prodrug approach is a very versatile strategy to improve the utility of pharmacologically active compounds; in fact, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (commonly known as ADMET) of pharmacologically active compounds can be optimized through this approach [2]. Thus, it is not surprising to find out that approximately 10% of all globally marketed medicines can be classified as prodrugs [2,8].

The prodrug approach is also used to increase the selectivity of drugs for their intended targets via site-selective delivery and/or site-selective bioconversion [8]. Improving selectivity by using the prodrug approach has been a major strategy to develop targeted therapy for cancer treatment [9]. Many conventional chemotherapeutic agents lack intrinsic target specificity and thus cause severe side effects due to their systemic toxicity. By using the prodrug approach to improve selectivity, lower doses of prodrugs can be given to achieve the same therapeutic effects as higher doses of the parent drugs, thus decreasing systemic toxicity and increasing the therapeutic utility of the drugs [10].

Tumor tissues can be selectively targeted, because tumor cells are often characterized by high expression of certain enzymes and elevated intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels in comparison with normal tissues [11,12]. Many prodrugs that harness overexpression of enzymes in tumor cells have been designed and tested [9]. Interestingly, while high GSH levels have been used as a mechanism for targeting tumor cells, depletion of GSH has been exploited as an anticancer approach [13].

In this article, we will review studies from our laboratory on the development of kidney- and tumor cell-selective prodrugs of the thiopurine drugs 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TG). 6-MP is an antineoplastic and immunosuppressive agent that is usually used to treat patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia and/or inflammatory bowel disease. 6-TG is an antimetabolite medication primarily used to treat patients with leukemia, inflammatory bowel disease, and/or psoriasis. 6-MP and 6-TG metabolism involves the formation of nucleotides that interfere with cellular functions by inhibiting de novo biosynthesis and interconversion of normal purines, whereas further metabolism and subsequent incorporation into nucleic acids are considered crucial steps in thiopurine cytotoxicity [14]. Both drugs are highly toxic and can cause bone marrow, liver, and gastrointestinal tract toxicities. Our novel prodrug approach to decrease the systemic toxicities and improve the clinical utility of 6-MP and 6-TG has been based upon our research on mechanisms of bioactivation and nephrotoxicity of the haloalkene trichloroethylene (TCE).

2. Physiological and biochemical features of the kidney and kidney cancer

As an important organ, the kidney has some unique physiological and biochemical characteristics, one of which is its reabsorption capability specifically present in the renal proximal tubule. Transporters are a critical player in the reabsorptive process; abundant organic anion transporters (OATs) are expressed in the renal proximal tubule and are responsible for the active reabsorption [15,16]. The kidney also plays a key role in the mercapturic acid pathway, by which many endogenous and exogenous electrophiles are detoxified through formation of GSH S-conjugates and subsequent conversion to N-acetylcysteine S-conjugates [17,18]. As a result, the kidney is characterized by the highest level of γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) activity, a cell surface enzyme responsible for hydrolysis of the γ-glutamyl bond of extracellular reduced and oxidized GSH [19,20]. In the mercapturic acid pathway, there is a thiomethyl shunt, in which a cysteine S-conjugate undergoes a β-elimination reaction under catalysis by cysteine S-conjugate β-lyses (β-lyses), producing a sulfur-containing fragment, pyruvate, and ammonia [18]. The liver and kidney usually have higher β-lyse activities than other organs or tissues [17,18].

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) ranks the sixth in the most frequent cancer list in developed countries [21]; there are about 209,000 new cases of RCC and more than 102,000 deaths worldwide. This corresponds to about 2–3% of all malignant tumors in the adult [22]. On average, metastatic dissemination is seen in 30% of new cases [23] and about 40% of patients relapse locally after nephrectomy [24]. The incidence of RCC has been rising over the last decades [25].

Surgery is the main treatment for the majority of kidney cancers. RCC is resistant to radio-, hormono-, and chemotherapy; even immunotherapy, which has nowadays evolved from non-specific to targeted therapy [26], is effective in only 15% of selected patients [27]. Although advances in the understanding of the oncogenic signal networks have led to several novel targeted therapies, these therapeutics still have significant toxicity and suffer from resistance developed after a few months [27,28].

Thus, it is of great value to investigate prodrugs that may selectively target tumor and kidney cells. Since our prodrug approaches were based upon the mechanisms of bioactivation and selective nephrotoxicity of the environmental contaminant TCE and related haloalkenes [29], in the following section we will briefly review the mechanisms of TCE nephrotoxicity.

3. Bioactivation of TCE and mechanisms of its nephrotoxicity

TCE is an industrial chemical that is used primarily as a solvent and is present widely as a contaminant in the environment. It has been classified as a human carcinogen (Group 1) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Human exposure to TCE is primarily associated with kidney cancer, and TCE is nephrotoxic in both mice and rats by all routes of exposure [29].

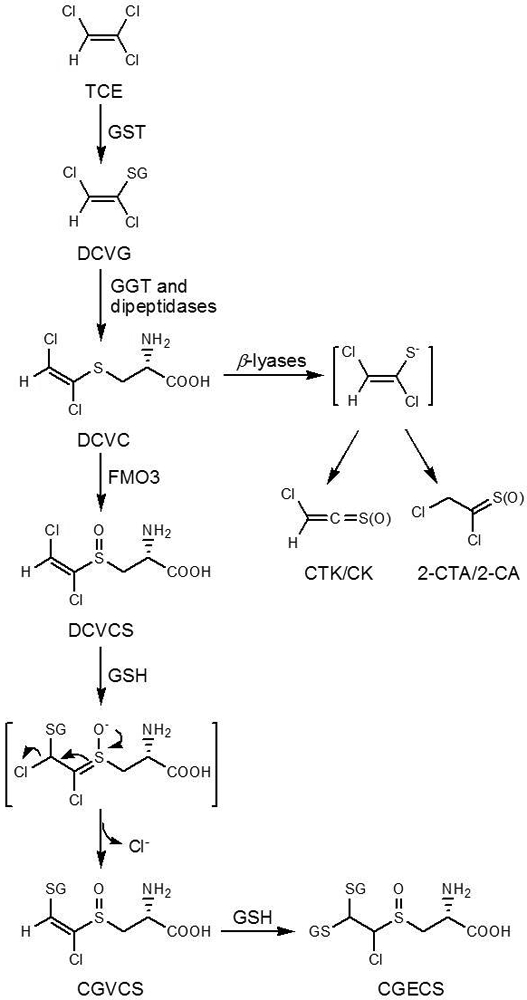

Nephrotoxicity of TCE has primarily been attributed to its metabolism via the mercapturic acid pathway (Figure 1), rather than metabolism via cytochrome P450s, although TCE metabolism is highly variable across sexes, species, tissues, and individuals [30–34]. Under catalysis of GSH S-transferases (GST), TCE is conjugated to GSH to form S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione (DCVG) [35], which is then biotransformed into S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC) by GGT and dipeptidases [34]. DCVC is a key metabolite responsible for nephrotoxicity of TCE [34,36], because human renal proximal tubular cells, either freshly isolated or cultured, were found to be sensitive to its toxicity [33,37]. DCVG was less toxic to these cells, but its toxicity increased to the same level as DCVC in the presence of exogenous GGT [37]; AT-125, a GGT inhibitor, protected against nephrotoxicity of DCVG [38], suggesting that DCVG nephrotoxicity was mediated by DCVC.

Figure 1.

Bioactivation of TCE via GSH conjugation and further renal metabolism of the formed GSH conjugate, S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione (DCVG), to yield the nephrotoxic metabolites, S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC) and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (DCVCS)

DCVC is a weak organic anion at physiological pH and thus needs to be transported into cells by OATs. As a result, OATs play an important role in nephrotoxicity of DCVC. Indeed, inhibition of OATs by probenecid decreased DCVC nephrotoxicity [38].

Once inside renal cells, DCVC can undergo further metabolism to be converted to reactive electrophiles [34], causing toxicity. Specifically, nephrotoxicity of DCVC has been attributed to two bioactivation pathways. In one pathway, DCVC undergoes a β-elimination reaction catalyzed by pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent β-lyases to generate four reactive electrophiles: chlorothioketene (CTK), 2-chlorothionoacetyl chloride (2-CTA), and their corresponding hydrolysis products chloroketene (CK) and 2-chloroacetyl chloride (2-CA) [31,39]. Pretreatment of rats with aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA), a selective inhibitor of β-lyases, reduced nephrotoxicity of DCVC; S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-DL-α-methylcysteine, which cannot be cleaved by β-lyases, was not nephrotoxic [37,38,40,41], providing evidence for this pathway. The second pathway implicated in DCVC nephrotoxicity is the oxidation mediated by flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) [42–44], which leads to the formation of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide (DCVCS; Figure 1), a highly reactive Michael acceptor [45]. In rats, the AOAA pretreatment did not protect against DCVCS nephrotoxicity but partly protected against DCVC nephrotoxicity [45], providing evidence for the in vivo presence of the two pathways.

DCVCS is a more potent nephrotoxicant compared to DCVC [45]; oxidation of DCVC results in the formation of a compound with a conjugated system (C=C-S=O). The conjugated system is structurally similar to α,β-unsaturated aldehyde/ketone (C=C-C=O) and thus is a Michael acceptor. Indeed, DCVCS can rapidly react with GSH under physiological conditions [43,46], and can readily modify and crosslink proteins [39,47,48].

An important characteristic of DCVCS is that it can react with two molecules of GSH, which occurs through a Michael addition-elimination mechanism. DCVCS first undergoes a Michael addition reaction with GSH; this reaction results in generation of an intermediate that readily undergoes an elimination reaction, losing a chloride anion to produce S-[1-chloro-2-(S-glutathionyl)vinyl]-L-cysteine sulfoxide (CGVCS; Figure 1) [46]. CGVCS retains the C=C-S=O conjugated system and thus can further react with another GSH molecule, yielding the final product S-[1-chloro-2,2-bis(S-glutathionyl)ethyl]-L-cysteine sulfoxide (CGECS; Figure 1). That is to say, one molecule of DCVCS can consume two molecules of GSH, which can result in intracellular GSH depletion. Indeed, rats administered 100 mg/kg DCVCS exhibited much lower renal reduced nonprotein thiol concentrations (27%) at 1 h compared to control rats [46].

Therefore, the kidney-selective toxicity of TCE can be attributed primarily to the following mechanisms: 1) biotransformation of DCVG into DCVC by GGT and dipeptidases; 2) transport of DCVC into proximal tubular cells by OATs; 3) β-lyase-dependent β-elimination reaction of DCVC to produce reactive electrophiles that modify cellular targets and alter cellular functions; 4) oxidation of DCVC mediated by FMO3 to generate DCVCS; 5) Michael addition-elimination reactions of DCVCS with protein thiols and GSH, impacting cellular functions and causing intracellular GSH depletion.

4. Kidney-selective β-lyase-dependent prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG

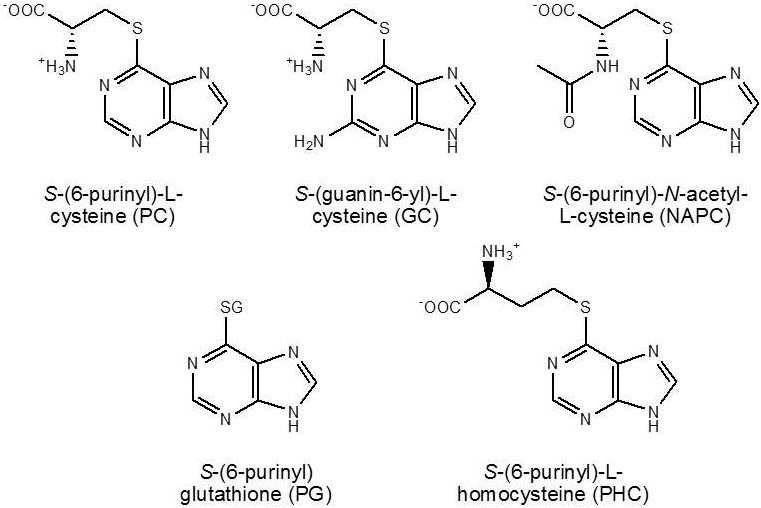

Inspired by understanding the biochemical basis for the kidney-specific toxicity of TCE, we synthesized S-(6-purinyl)-L-cysteine (PC) and S-(guanin-6-yl)-L-cysteine (GC; Figure 2), which are potential kidney-selective prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG, respectively. Design of PC and GC exploits high expression of OATs in the renal proximal tubule and high activity of β-lyases in the kidney. Like DCVC, both were cysteine S-conjugates.

Figure 2.

Structures of the kidney-selective prodrugs based on β-elimination reactions of cysteine S-conjugates catalyzed by β-lyases

As expected, PC was found to be a good substrate for renal β-lyases and indeed exhibited renal selectivity. In rats administered PC, 6-MP and its further metabolites, 6-methyl mercaptopurine and 6-thiouric acid, were detected in the kidney, liver, and plasma. The total concentrations of metabolites in the kidney were approximately 90-fold greater than those in plasma, and were 2.3-fold greater than those in the liver [49]. GC was also metabolized to yield 6-TG; in rats administered 400 μmol/kg GC, renal 6-TG concentration at 30 min was nearly 4-fold higher than hepatic concentration. Furthermore, both prodrugs did not exhibited acute renal toxicity at 400 μmol/kg (94 mg/kg for PC and 100 mg/kg for GC) [50].

As the case of DCVC, OATs may also significantly contribute to the renal selectivity of the prodrugs. Rats that were given probenecid before PC administration exhibited lower biotransformation rates; specifically, the total kidney metabolite concentrations were reduced by 36% [51].

A further increase in the selectivity of the prodrugs was accomplished by introducing additional moieties in the molecules, removal of which required extra enzymatic and/or non-enzymatic step(s). In this regard, S-(6-purinyl)-N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAPC) and S-(6-purinyl)glutathione (PG; Figure 2) were prepared and were found to indeed exhibit higher renal selectivity than PC. In rats given 800 μmol/kg of these prodrugs, the concentrations of the total metabolites in the kidney at 30 min were 17.6- and 6.5-fold higher than those in the liver, respectively [52]. In comparison with PC, NAPC carries an additional acetyl group and thus needs deacetylase to be converted to PC; PG, as a GSH conjugate, requires GGT and dipeptidases to be converted to PC. Providing support for the bioactivation of PG to 6-MP in renal cells, we found that inhibition of GGT by acivicin increased accumulation of PG in cells and stimulation of the activity of β-lyses by α-keto-γ-methiolbutyrate decreased accumulation of PG [53]. The finding that 6-chloropurine-treated rats formed PG and 6-MP provided further evidence for PG metabolism to 6-MP in vivo [54]. In addition, S-(6-purinyl)-L-homocysteine (PHC; Figure 2) was synthesized and exhibited a slightly improved kidney selectivity compared to PC. PHC was thought to undergo an initial transamination reaction catalyzed by β-lyases to generate 4-(6-purinyl)thio-2-oxobutanoic acid, followed by a non-enzymatic β-elimination reaction to yield 6-MP and 2-oxo-3-butenoic acid [52].

Although PC, GC, NAPC, PG, and PHC were all shown to be kidney-selective prodrugs of 6-MP or 6-TG, the utility of these prodrugs was limited by their slow turnover rates. In rats given 400 μmol/kg of PC and GC, the percentages of the doses excreted in the urine as metabolites within 24 h were only ∼3% and 1%, respectively [50,51]. Introduction of additional moieties increased the renal selectivity, but at a cost to further lower the turnover rates. Specifically, the concentrations of the total metabolites in the kidney at 30 min after NAPC, PG, and PHC administration were nearly 10%, 1%, and 100%, respectively, of those obtained with PC [52].

5. Tumor-selective GSH-dependent Michael acceptors as prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG

Due to the low conversion rates of the above described prodrugs, we investigated 6-MP and 6-TG derivatives that can release the parent drugs through Michael addition-elimination reactions with GSH. The release mechanism of 6-MP and 6-TG was expected to be in analogy to the reaction of DCVCS with GSH to discharge chloride anion (Figure 1). The latter reaction has been verified to occur both in vitro and in vivo. Such a mechanism is dependent on GSH, which is the most abundant thiol in eukaryotic cells and plays important roles in a myriad of cellular activities [13,55–57]. In malignant tumor cells, GSH concentrations are higher in comparison with the cells of normal tissues, which contributes to multidrug and radiation resistance of tumor cells [13,58]. Thus, prodrugs whose bioactivation requires GSH may exhibit tumor cell-selectivity.

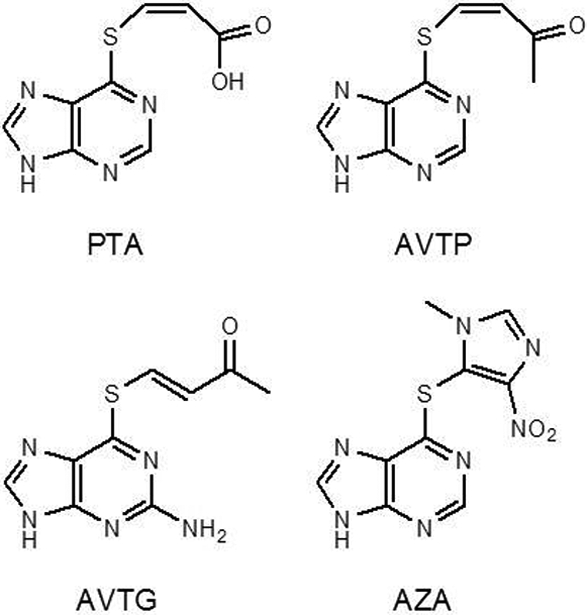

The first prodrug to be designed by this strategy was cis-3-(9H-purin-6-ylthio)acrylic acid (PTA; Figure 3). PTA has an α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acid moiety and thus was expected to serve as a Michael acceptor. The carboxylic acid moiety was retained in its structure in anticipation that it could be transported into renal proximal tubular cells by OATs, enhancing its intracellular accumulation and renal selectivity [59].

Figure 3.

The structures of PTA, AVTP, and AVTG, three 6-MP and 6-TG prodrugs investigated in our laboratory, which exploit the Michael addition-elimination reaction with GSH as the mechanism of release of the parent drugs, and the structure of AZA, an established prodrug of 6-MP

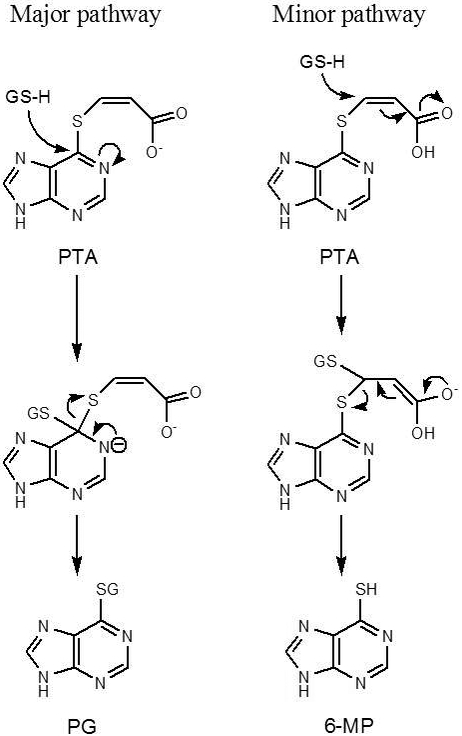

However, it turned out that PTA was only a limited success [59]. The reaction of PTA with GSH in pH 7.4 buffer indeed generated 6-MP as anticipated, but 6-MP was not the major product; instead, PG (Figure 2) was the predominant product. Clearly, in the reaction of PTA with GSH, two competing mechanisms are involved. The formation of PG is apparently caused by an attack of GSH at C6, and the formation of 6-MP can be attributed to the Michael addition-elimination reaction (Figure 4) [59].

Figure 4.

The two competing mechanisms of PTA biotransformation in the presence of GSH

Like PC and GC, PTA exhibited a low conversion rate to 6-MP. Even for the major product PG, the conversion rate reached only 1.7% [59], thus severely hampering PTA application as an effective prodrug. The low conversion rates were caused by the low reactivity of PTA as a Michael acceptor toward GSH, which could be attributed to the fact that at physiological pH PTA was deprotonated, thus markedly decreasing the electrophilicity of the β-carbon and hence decreasing its reactivity.

To address the deprotonation issue in PTA, two prodrugs with similar structures, cis-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)purine (AVTP) and trans-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)guanine (AVTG; Figure 3), were prepared. In the two prodrugs, a methyl vinyl ketone moiety was substituted for the carboxylic acid moiety in PTA.

AVTP and AVTG indeed exhibited high reactivity toward GSH and excellent conversion rates to yield 6-MP and 6-TG in comparison with azathioprine (AZA), a prodrug of 6-MP that has long been used clinically (Figure 3) [60]. In incubation with GSH in buffer, the parent drugs were rapidly produced; approximately 60% of prodrugs were converted to 6-MP and 6-TG at 10 min [60]. When two human renal carcinoma cell lines were treated with AVTG, intracellular GSH concentrations rapidly decreased and reached the lowest at 20 min; at this time point the GSH concentrations were only ∼10% of those before incubation. On the other hand, intracellular 6-TG concentrations increased over time and reached the highest at 10 min, and virtually kept constant from 10 to 20 min. The conversion to 6-TG was clearly GSH-dependent, because GSH-depleted cells by preincubation with diethyl maleate (DEM) showed much lower 6-TG concentrations in comparison to the cells untreated with DEM. Importantly, the intracellular 6-TG concentrations in AVTG-treated cells were approximately 7-fold higher than those observed in cells incubated with equimolar 6-TG concentrations, indicating that the prodrug delivered more 6-TG to cells than did 6-TG itself. Therefore, the prodrug significantly increased the efficiency of drug delivery. Interestingly, the prodrugs had comparable or lower IC50 values in more than 50 tumor cell lines in the National Cancer Institute’s anticancer drug screen, compared to their corresponding parent drugs (Table 1) [61]; in fact, their IC50 values in tumor cells tested were much lower than AZA [60].

Table 1.

The median TGI, GI50, and LC50 values obtained with 6-TG, 6-MP, AVTP, and AVTG in the National Cancer Institute anticancer screena

| Cytotoxicity parameter |

6-MP | 6-TG | AVTP | AVTG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGI (μM) | > 100 | 44.8 | 4.6 | 12.9 |

| GI50 (μM) | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| LC50 (μM) | > 100 | > 100 | 38.6 | 76.2 |

TGI refers to the drug concentration resulting in total growth inhibition. GI50 refers to the drug concentration that reduces tumor cell growth by 50% compared with untreated controls. LC50 refers to the drug concentration required to decrease tumor cell numbers by 50% compared with untreated controls.

Transformation of AVTP and AVTG into the parent drugs is a non-enzymatic reaction, but GST were found to enhance the rates of these reactions. Among 13 human GST examined, GST M1–1 and A4–4 were the most efficient catalysts with AVTG, whereas GST M1–1 and M2–2 had the highest activity with AVTP [62].

As prodrugs, AVTP and AVTG also exhibited success by another criterion, that is, the low systemic toxicity. In mice, the prodrugs did not cause decreases in white blood cell counts, whereas 6-TG led to decreases by 50 to 60% either in equimolar or 60% lower doses of the prodrugs [60]. Even after multiple treatments, AVTP still did not show toxicity as evaluated by peripheral WBC and RBC counts, myeloid:erythroid ratios in the bone marrow, intestinal epithelial crypt cell apoptosis, and histopathological examination of the kidney and liver. Although AVTG exhibited some toxicity in the experiment, its toxicity was still lower than that of 6-TG [63].

6. Summary and conclusions

The prodrug approach is an effective strategy to improve the target selectivity of a parent drug. Improvement of the target selectivity can increase the efficiency of the parent drug and reduce its systemic toxicity. The target selectivity is especially important for chemotherapeutic drugs, because these drugs are designed to kill tumor cells and thus are highly cytotoxic.

Tumor cells have many aberrant markers that can be harnessed to design targeted prodrugs. In this review, we demonstrated a successful approach to target tumor cells by exploiting their high GSH concentrations. The approach is to modify a drug by attaching a methyl vinyl ketone moiety to the drug, generating a Michael acceptor prodrug. This prodrug reacts with GSH to undergo a Michael addition-elimination reaction to release the parent drug. Such prodrugs have been shown to decrease intracellular GSH concentrations and release the active therapeutic drugs simultaneously. The associated GSH depletion may potentiate cytotoxicity of the parent drugs.

AVTP and AVTG, the prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG, exhibited higher growth-inhibitory activities and cytotoxicity than the corresponding parent drugs against multiple tumor cell lines in the National Cancer Institute’s anticancer drug screen. The prodrugs delivered more parent drugs to tumor cells in vitro than did 6-MP or 6-TG itself and exhibited less in vivo toxicity in mice than 6-TG. Therefore, further investigations into the potential therapeutic utility of AVTP and AVTG are warranted. The two prodrugs could particularly be useful in treatment of liver and kidney cancers since these tissues have high GSH concentrations and high GST activities in comparison with other tissues [13,64]. AVTP and AVTG might also have capacity to selectively target cells expressing high levels of specific GST isoforms, because they exhibited different selectivities toward human GST. Collectively, because of the above described results, future research should examine the in vivo tumor cell selectivity of AVTP and AVTG. Studies to assess their cytotoxicity in tumor cells resistant to traditional chemotherapy are also warranted.

7. Expert opinion

A variety of strategies can be used to design tumor tissue-/cell-targeted prodrugs. Most strategies harness metabolic activation through enzymes that are abnormally expressed in tumor tissues/cells or are deliberately delivered to tumor tissues/cells (antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy and gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy) [1]. Targeting tissue- or cell-specific endogenous transporters are often exploited as well [2]. Other biochemical properties that are aberrant in tumor tissues/cells, such as hypoxia, low pH, and high GSH concentrations, can also be used as targets [2,65,66]. Among these strategies, prodrugs using high GSH concentrations as a bioactivation mechanism are quite limited [66]; such prodrugs include JS-K (a prodrug of nitric oxide with excellent anticancer activity [67–69]), DCM-S-CPT and FA-CPT (prodrugs of the anticancer drug camptothecin [70,71]), and AZA. JS-K and AZA, like AVTP and AVTG, are Michael acceptors and are bioactivated by Michael addition-elimination reactions in the presence of GSH, which can be facilitated by GST [72–74]. On the other hand, DCM-S-CPT and FA-CPT contain disulfide bonds, which are cleaved through reduction by GSH to release the active parent drugs [66,70,71].

Bioactivation of prodrugs that exploit high GSH concentrations as the bioactivation mechanism may hold great potential for development of prodrugs with excellent anticancer activity, because such prodrugs can cause GSH depletion while releasing the parent drugs. Intracellular GSH depletion can potentiate cytotoxicity of the parent drugs possibly by enhancing intracellular oxidative stress. In this regard, APR-246, an anticancer drug in early-phase clinical trials via reactivation of mutant p53 [75], was found to cause GSH depletion through its metabolite methylene quinuclidinone, a Michael acceptor [76,77], and was reported to have strong synergy with chemotherapeutic drugs such as cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and doxorubicin [76].

GSH has also been known to play a pivotal role in initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancer [78]. Contrary to the conventional view that antioxidants might benefit high-risk patients by reducing the rate of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced mutations and delaying cancer initiation, mounting evidence suggests that GSH actually protects cancer cells from harmful effects of ROS during cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis [78,79].

Cancer cells are long known to sustain higher ROS levels compared to normal cells [80], but they are also more sensitive than normal cells to further oxidative insults [81,82]. A vast majority of metastasizing cancer cells are killed by oxidative stress at multiple stages of the metastatic process [78]. To avoid the detrimental effects of ROS, cancer cells actively upregulate multiple antioxidant systems [58,80,83,84]. As a result, many cancer cells contain high GSH concentrations and overexpress the related enzymes, such as GGT [20] and GST [64,85]; high GSH concentrations are generally beneficial to initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancers [13,78,79,84,86,87]. Multidrug and radiation resistance of many tumors appears to be associated with higher GSH levels and/or lower ROS levels in the cancer cells [13,58,86,88]. Consequently, it has been proposed that cancer patients should be treated with pro-oxidants that exacerbate oxidative stress or block metabolic adaptations that confer oxidative stress resistance [78,80,89]. As an example, although it was initially designed to reactivate the functions of mutant p53 protein, APR-246 was later found to be able to induce intracellular GSH depletion and oxidative stress, which was independent of mutant p53 reactivation but was critical to its therapeutic activity [90]. Apparently, GSH depletion in cancer cells or in the tumor microenvironment is highly desirable to treat cancers.

GSH depletion can directly induce cell death as well. Ferroptosis, a novel form of regulated cell death [91], is characterized by GSH depletion, inactivation of GSH peroxidase 4 [92], and resulted iron-dependent accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides to lethal levels [93]. Although the GSH depletion in ferroptosis is induced specifically by the small molecule erastin through inhibition of the import of cystine, GSH depletion caused by other agents, e.g., L-buthionine-sulfoximine, an inhibitor of GSH synthesis that is used routinely to deplete intracellular GSH, is also capable of inducing ferroptosis [92]. Importantly, agents that conjugate to GSH can induce a ferroptosis-like cell death in cancer cells, especially in mutant p53 tumor cells [82,90]. This is critical because TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in cancers [94].

Given such high dependence of cancer cells on GSH, targeting GSH may represent a promising direction to develop prodrugs to whom cancer cells are less likely to develop resistance. Although cells contain multiple antioxidant systems, it may be difficult for cells to completely replace the functions of GSH with other alternative systems due to its high concentrations and numerous roles in cellular activities. In terms of its significance in initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancers as discussed above, GSH can be considered a cornerstone in the development of cancers. Therefore, GSH may be an excellent target that deserves more attention and should have a position in anticancer drug development targeting tumor-supportive cellular machineries [95].

Article Highlights.

Many conventional chemotherapeutic agents, like 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TG), lack intrinsic target specificity and thus cause severe side effects due to their systemic toxicity. Increasing their selectivity by the prodrug approach may reduce systemic toxicity. Design of the prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG exploits high activities of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases (β-lyases) and high glutathione (GSH) concentrations in kidney and tumor cells. These approaches were inspired by our studies on mechanisms of kidney-selective toxicity of trichloroethylene (TCE), an environmental pollutant.

Nephrotoxicity of TCE is attributed to its metabolism via the mercapturic acid pathway to form S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC). DCVC can either undergo a β-elimination reaction catalyzed by β-lyases to form a reactive thiol, or be oxidized by flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 to form DCVC sulfoxide, a Michael acceptor that can readily react with GSH and cause intracellular GSH depletion.

Several kidney-selective β-lyase-dependent prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG were developed. These prodrugs exhibited renal selectivity and low systemic toxicity in rats. However, low turnover rates limited their potential utility.

Tumor-selective GSH-dependent Michael acceptor prodrugs of 6-MP and 6-TG were then developed. These prodrugs carried vinyl carboxylic acid- or methyl vinyl ketone-moieties. They reacted with GSH to release the parent drugs and caused GSH depletion. Among them, cis-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)purine (AVTP) and trans-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)guanine (AVTG) exhibited excellent anticancer activities against approximately 50 tumor cell lines from different tissues in the National Cancer Institute’s anticancer drug screen. The two prodrugs delivered more thiopurines to tumor cells in vitro than did 6-MP or 6-TG itself and exhibited similar or higher growth-inhibitory activities in vitro compared to 6-MP or 6-TG. Moreover, they showed less in vivo toxicity in mice than 6-TG after single- and multiple-dose regimens.

Based on the success in the design of AVTP and AVTG, it is proposed that targeting GSH has great potential for development of prodrugs that could have utility against tumor cells resistant to conventional chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health via grants GM40375, R01DK044295 and R01ES06841 and via a Biomedical Research Support Grant from the University of Wisconsin- Madison.

Abbreviations:

- 2-CA

2-chloroacetyl chloride

- 2-CTA

2-chlorothionoacetyl chloride

- 6-MP

6-mercaptopurine

- 6-TG

6-thioguanine

- β-lyases

cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases

- AOAA

aminooxyacetic acid

- AVTG

trans-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)guanine

- AVTP

cis-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)purine

- AZA

azathioprine

- CGECS

S-[1-chloro-2,2-bis(S-glutathionyl)ethyl]-L-cysteine sulfoxide

- CGVCS

S-[1-chloro-2-(S-glutathionyl)vinyl]-L-cysteine sulfoxide

- CK

chloroketene

- CTK

chlorothioketene

- DCVC

S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine

- DCVCS

S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide

- DCVG

S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione

- DEM

diethyl maleate

- FMO3

flavin-containing monooxygenase 3

- GC

S-(guanin-6-yl)-L-cysteine

- GGT

γ-glutamyltransferase

- GSH

glutathione

- GST

GSH S-transferases

- NAPC

S-(6-purinyl)-N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- OATs

organic anion transporters

- PC

S-(6-purinyl)-L-cysteine

- PG

S-(6-purinyl)glutathione

- PHC

S-(6-purinyl)-L-homocysteine

- PTA

cis-3-(9H-purin-6-ylthio)acrylic acid

- RCC

renal cell carcinoma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TCE

trichloroethylene

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer Disclosures:

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

References

- 1.Rautio J, Kumpulainen H, Heimbach T, et al. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huttunen KM, Raunio H, Rautio J. Prodrugs--from serendipity to rational design. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:750–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A good review for prodrugs.

- 3.Abet V, Filace F, Recio J, et al. Prodrug approach: an overview of recent cases. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;127:810–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walther R, Rautio J, Zelikin AN. Prodrugs in medicinal chemistry and enzyme prodrug therapies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;118:65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheetham AG, Chakroun RW, Ma W, Cui H. Self-assembling prodrugs. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:6638–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clas S-D, Sanchez RI, Nofsinger R. Chemistry-enabled drug delivery (prodrugs): recent progress and challenges. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stella VJ. Prodrugs: some thoughts and current issues. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:4755–4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rautio J, Kärkkäinen J, Sloan KB. Prodrugs - Recent approvals and a glimpse of the pipeline. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;109:146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giang I, Boland EL, Poon GM. Prodrug applications for targeted cancer therapy. AAPS J. 2014;16:899–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasarao M, Low PS. Ligand-targeted drug delivery. Chem Rev. 2017;117:12133–12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber CE, Kuo PC. The tumor microenvironment. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graves EE, Maity A, Le QT. The tumor microenvironment in non-small-cell lung cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estrela JM, Ortega A, Obrador E. Glutathione in cancer biology and therapy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2006;43:143–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An excellent review for GSH in cancer biology and therapy.

- 14.Gunnarsdottir S, Elfarra AA. Distinct tissue distribution of metabolites of the novel glutathione-activated thiopurine prodrugs cis-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)purine and trans-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)guanine and 6-thioguanine in the mouse. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigam SK, Bush KT, Martovetsky G, et al. The organic anion transporter (OAT) family: a systems biology perspective. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:83–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin J, Wang J. Renal drug transporters and their significance in drug-drug interactions. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper AJ, Pinto JT. Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases. Amino Acids. 2006;30:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper AJ, Krasnikov BF, Niatsetskaya ZV, et al. Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases: important roles in the metabolism of naturally occurring sulfur and selenium-containing compounds, xenobiotics and anticancer agents. Amino Acids. 2011;41:7–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanigan MH, Frierson HF Jr. Immunohistochemical detection of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in normal human tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanigan MH. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase: redox regulation and drug resistance. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;122:103–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2009;373:1119–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam JS, Leppert JT, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA. Novel approaches in the therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol. 2005;23:202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 (Suppl. 3):iii49–iii56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedke J, Gouttefangeas C, Singh-Jasuja H, et al. Targeted therapy in renal cell carcinoma: moving from molecular agents to specific immunotherapy. World J Urol. 2014;32:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dormoy V, Jacqmin D, Lang H, Massfelder T. From development to cancer: lessons from the kidney to uncover new therapeutic targets. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3609–3617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pracht M, Berthold D. Successes and limitations of targeted therapies in renal cell carcinoma. Prog Tumor Res. 2014;41:98–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rusyn I, Chiu WA, Lash LH, et al. Trichloroethylene: mechanistic, epidemiologic and other supporting evidence of carcinogenic hazard. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141:55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • An excellent review for trichloroethylene.

- 30.Lash LH, Chiu WA, Guyton KZ, Rusyn I. Trichloroethylene biotransformation and its role in mutagenicity, carcinogenicity and target organ toxicity. Mutat Res. 2014;762:22–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irving RM, Elfarra AA. Role of reactive metabolites in the circulation in extrahepatic toxicity. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8:1157–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lash LH, Xu Y, Elfarra AA, et al. Glutathione-dependent metabolism of trichloroethylene in isolated liver and kidney cells of rats and its role in mitochondrial and cellular toxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:846–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cummings BS, Lash LH. Metabolism and toxicity of trichloroethylene and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine in freshly isolated human proximal tubular cells. Toxicol Sci. 2000;53:458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lash LH, Fisher JW, Lipscomb JC, Parker JC. Metabolism of trichloroethylene. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl. 2):177–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lash LH, Putt DA, Brashear WT, et al. Identification of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione in the blood of human volunteers exposed to trichloroethylene. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;56:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lash LH, Parker JC, Scott CS. Modes of action of trichloroethylene for kidney tumorigenesis. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl. 2):225–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JC, Stevens JL, Trifillis AL, Jones TW. Renal cysteine conjugate β-lyase-mediated toxicity studied with primary cultures of human proximal tubular cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;103:463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elfarra AA, Jakobson I, Anders MW. Mechanism of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione-induced nephrotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barshteyn N, Elfarra AA. Globin monoadducts and cross-links provide evidence for the presence of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide, chlorothioketene, and 2-chlorothionoacetyl chloride in the circulation in rats administered S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1629–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lash LH, Elfarra AA, Anders MW. Renal cysteine conjugate β-lyase. Bioactivation of nephrotoxic cysteine S-conjugates in mitochondrial outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5930–5935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elfarra AA, Lash LH, Anders MW. Alpha-ketoacids stimulate rat renal cysteine conjugate beta-lyase activity and potentiate the cytotoxicity of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;31:208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sausen PJ, Elfarra AA. Cysteine conjugate S-oxidase. Characterization of a novel enzymatic activity in rat hepatic and renal microsomes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6139–6145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ripp SL, Overby LH, Philpot RM, Elfarra AA. Oxidation of cysteine S-conjugates by rabbit liver microsomes and cDNA-expressed flavin-containing mono-oxygenases: studies with S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine, S-(1,2,2-trichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine, S-allyl-L-cysteine, and S-benzyl-L-cysteine. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krause RJ, Lash LH, Elfarra AA. Human kidney flavin-containing monooxygenases and their potential roles in cysteine S-conjugate metabolism and nephrotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lash LH, Sausen PJ, Duescher RJ, et al. Roles of cysteine conjugate β-lyase and S-oxidase in nephrotoxicity: studies with S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:374–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sausen PJ, Elfarra AA. Reactivity of cysteine S-conjugate sulfoxides: formation of S-[1-chloro-2-(S-glutathionyl)vinyl]-L-cysteine sulfoxide by the reaction of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide with glutathione. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;4:655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Demonstrated that the reaction of DCVCS with GSH can occur both in vitro and in vivo, and DCVCS treatment in rats resulted in GSH depletion in the kidney.

- 47.Irving RM, Brownfield MS, Elfarra AA. N-biotinyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide as a potential model for S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide: characterization of stability and reactivity with glutathione and kidney proteins in vitro. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1915–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barshteyn N, Elfarra AA. Detection of multiple globin monoadducts and cross-links after in vitro exposure of rat erythrocytes to S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide and after in vivo treatment of rats with S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine sulfoxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1716–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hwang IY, Elfarra AA. Cysteine S-conjugates may act as kidney-selective prodrugs: formation of 6-mercaptopurine by the renal metabolism of S-(6-purinyl)-L-cysteine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:448–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elfarra AA, Duescher RJ, Hwang IY, et al. Targeting 6-thioguanine to the kidney with S-(guanin-6-yl)-L-cysteine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1298–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwang IY, Elfarra AA. Kidney-selective prodrugs of 6-mercaptopurine: biochemical basis of the kidney selectivity of S-(6-purinyl)-L-cysteine and metabolism of new analogs in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elfarra AA, Hwang IY. Targeting of 6-mercaptopurine to the kidneys. Metabolism and kidney-selectivity of S-(6-purinyl)-L-cysteine analogs in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:841–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lash LH, Shivnani A, Mai J, et al. Renal cellular transport, metabolism, and cytotoxicity of S-(6-purinyl)glutathione, a prodrug of 6-mercaptopurine, and analogues. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1341–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hwang IY, Elfarra AA. Detection and mechanisms of formation of S-(6-purinyl)glutathione and 6-mercaptopurine in rats given 6-chloropurine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sies H Glutathione and its role in cellular functions. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:916–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballatori N, Krance SM, Notenboom S, et al. Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol Chem. 2009;390:191–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Ciriolo MR. Glutathione: new roles in redox signaling for an old antioxidant. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:780–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunnarsdottir S, Elfarra AA. Glutathione-dependent metabolism of cis-3-(9H-purin-6-ylthio)acrylic acid to yield the chemotherapeutic drug 6-mercaptopurine: evidence for two distinct mechanisms in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:950–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gunnarsdottir S, Rucki M, Elfarra AA. Novel glutathione-dependent thiopurine prodrugs: evidence for enhanced cytotoxicity in tumor cells and for decreased bone marrow toxicity in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The first report on AVTP and AVTG.

- 61.Gunnarsdottir S, Elfarra AA. Cytotoxicity of the novel glutathione-activated thiopurine prodrugs cis-AVTP [cis-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)purine] and trans-AVTG [trans-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)guanine] results from the National Cancer Institute’s anticancer drug screen. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Demonstrated the excellent anticancer potential of AVTP and AVTG against more than 50 tumoe cell lines in the National Cancer Institute’s anticancer drug screen.

- 62.Eklund BI, Gunnarsdottir S, Elfarra AA, Mannervik B. Human glutathione transferases catalyzing the bioactivation of anticancer thiopurine prodrugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1829–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrated that GST could facilitate bioactivation of AVTP and AVTG.

- 63.Gunnarsdottir S, Rucki M, Phillips LA, et al. The glutathione-activated thiopurine prodrugs trans-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)guanine and cis-6-(2-acetylvinylthio)purine cause less in vivo toxicity than 6-thioguanine after single- and multiple-dose regimens. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1211–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Di Pietro G, Magno LA, Rios-Santos F. Glutathione S-transferases: an overview in cancer research. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6:153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phillips RM. Targeting the hypoxic fraction of tumours using hypoxia-activated prodrugs. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:441–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang X, Li X, You Q, Zhang X. Prodrug strategy for cancer cell-specific targeting: a recent overview. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;139:542–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shami PJ, Saavedra JE, Bonifant CL, et al. Antitumor activity of JS-K [O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl) 1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate] and related O2-aryl diazeniumdiolates in vitro and in vivo. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4356–4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiziltepe T, Hideshima T, Ishitsuka K, et al. JS-K, a GST-activated nitric oxide generator, induces DNA double-strand breaks, activates DNA damage response pathways, and induces apoptosis in vitro and in vivo in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2007;110:709–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maciag AE, Chakrapani H, Saavedra JE, et al. The nitric oxide prodrug JS-K is effective against non-small-cell lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo: involvement of reactive oxygen species. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu X, Sun X, Guo Z, et al. In vivo and in situ tracking cancer chemotherapy by highly photostable NIR fluorescent theranostic prodrug. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3579–3588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu Z, Hou M, Shi X, et al. Rapidly cell-penetrating and reductive milieu-responsive nanoaggregates assembled from an amphiphilic folate-camptothecin prodrug for enhanced drug delivery and controlled release. Biomater Sci. 2017;5:444–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shami PJ, Saavedra JE, Wang LY, et al. JS-K, a glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide donor of the diazeniumdiolate class with potent antineoplastic activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:409–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Watanabe A, Hobara N, Nagashima H. Demonstration of enzymatic activity converting azathioprine to 6-mercaptopurine. Acta Med Okayama. 1978;32:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amin J, Huang B, Yoon J, Shih DQ. Update 2014: advances to optimize 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine to reduce toxicity and improve efficacy in the management of IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bykov VJ, Issaeva N, Shilov A, et al. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nat Med. 2002;8:282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bykov VJ, Zhang Q, Zhang M, et al. Targeting of mutant p53 and the cellular redox balance by APR-246 as a strategy for efficient cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2016;6:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tessoulin B, Descamps G, Moreau P, et al. PRIMA-1Met induces myeloma cell death independent of p53 by impairing the GSH/ROS balance. Blood. 2014;124:1626–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gill JG, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer, oxidative stress, and metastasis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2016;81:163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An excellent review about the advances on cancer and oxidative stress.

- 79.Harris IS, Treloar AE, Inoue S, et al. Glutathione and thioredoxin antioxidant pathways synergize to drive cancer initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Demonstrated that GSH was required for cancer initiation.

- 80.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raj L, Ide T, Gurkar AU, et al. Selective killing of cancer cells by a small molecule targeting the stress response to ROS. Nature. 2011;475:231–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 82.Liu DS, Duong CP, Haupt S, et al. Inhibiting the system xC-/glutathione axis selectively targets cancers with mutant-p53 accumulation. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475:106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schafer ZT, Grassian AR, Song L, et al. Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment. Nature. 2009;461:109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McIlwain CC, Townsend DM, Tew KD. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms: cancer incidence and therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:1639–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Estrela JM, Ortega A, Mena S, et al. Glutathione in metastases: from mechanisms to clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2016;53:253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A good review about GSH.

- 87.Chen EI, Hewel J, Krueger JS, et al. Adaptation of energy metabolism in breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1472–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cheteh EH, Augsten M, Rundqvist H, et al. Human cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance glutathione levels and antagonize drug-induced prostate cancer cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trachootham D, Zhou Y, Zhang H, et al. Selective killing of oncogenically transformed cells through a ROS-mediated mechanism by β-phenylethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:241–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Clemons NJ, Liu DS, Duong CP, Phillips WA. Inhibiting system xC- and glutathione biosynthesis - a potential Achilles’ heel in mutant-p53 cancers. Mol Cell Oncol. 2017;4:e1344757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, et al. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171:273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A comprehensive discussion on ferroptosis.

- 94.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dobbelstein M, Moll U. Targeting tumour-supportive cellular machineries in anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:179–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An excellent review about the logic behind anticancer drug development.