Abstract

Context.

Interprofessional teams often develop a care plan before engaging in a family meeting in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit (CICU)—a process that can affect the course of the family meeting and alter team dynamics but that has not been studied.

Objectives.

To characterize the types of interactions that interprofessional team members have in pre—family meeting huddles in the pediatric CICU by 1) evaluating the amount of time each team member speaks; 2) assessing team communication and teamwork using standardized instruments; and 3) measuring team members’ perceptions of collaboration and satisfaction with decision making.

Methods.

We conducted a prospective observational study in a pediatric CICU. Subjects were members of the interprofessional team attending preparation meetings before care meetings with families of patients admitted to the CICU for longer than two weeks. We quantitatively coded the amount each team member spoke. We assessed team performance of communication and teamwork using the PACT-Novice tool, and we measured perception of collaboration and satisfaction with decision making using the Collaboration and Satisfaction About Care Decisions questionnaire.

Results.

Physicians spoke for an average of 83.9% of each meeting’s duration (SD 7.5%); nonphysicians averaged 9.9% (SD 5.2%). Teamwork behaviors were present and adequately performed as judged by trained observers. Significant differences in physician and nonphysician perceptions of collaboration were found in three of 10 observed meetings.

Conclusion.

Interprofessional team members’ interactions in team meetings provide important information about team dynamics, revealing potential opportunities for improved collaboration and communication in team meetings and subsequent family meetings.

Keywords: Interprofessional communication, team communication, cardiac intensive care unit, pediatrics, teamwork

The National Academy of Medicine has stated that collaborative interprofessional teams are best positioned to meet the challenges of an evolving health system,1 as patients receive safer, higher quality care when providers work effectively in a team.2 Interprofessional teamwork is vitally important in complex health care environments like pediatric intensive care units (ICUs).

Interprofessional clinical teams caring for critically ill patients encounter challenges in coordinating their teamwork. For example, as compared to teams in the business world, clinical teams routinely are comprised of a large number of rotating clinicians from a variety of disciplines,3 which can undermine high-quality teamwork and communication within teams.4,5 Other challenges to teamwork and good communication include environmental rudeness6; high prevalence of conflict7; contradictory and negatively reinforcing aspects of medical cultures8; and daily difficulties of collectively managing clinical uncertainty and sharing bad news.9 Optimizing team communication and collaboration is essential to both maintain patient safety and ensure consistent messaging to families about the patient’s care.10,11 However, despite consensus about the value of interprofessional teamwork and communication, little is known about the process interprofessional teams use to communicate and make decisions about care plan development during team meetings that often precede and influence the course of subsequent family meetings. A clearer understanding of both the processes used by teams and the impact these processes have on team members’ perception of collaboration can identify opportunities for improvement in family meeting preparation.

Accordingly, the goals of this observational study in the pediatric cardiac ICU were to 1) evaluate the amount of time each team member speaks; 2) assess team performance; and 3) measure team members’ perceptions of collaboration and satisfaction with decision making.

Methods

As part of a prospective, mixed-methods cohort study, we collected data at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) over four months in 2016. Our institution is a large, northeast tertiary care center with a 26-bed CICU that has extensive staffing and utilization: the unit has 11 intensivists, seven nurse practitioners, 127 nurses, and two social workers, and there are approximately 1000 admissions per year.

Subjects were members of the interprofessional team attending a face-to-face weekly chronic care rounds meeting in the CICU. Staff attending the meetings from the CICU included CICU attendings; advanced practice providers; nursing supervisors; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; dieticians; and bedside nurses. Consulting services, primary care providers, and other professionals from beyond the CICU and its associated cardiac unit are routinely invited to participate in meetings about patients for whom they are caring. We considered these non-CICU providers to be part of the interprofessional team for a given week’s meeting because they were involved in the shared care of the patient. The explicitly stated goal of each meeting was to review the medical course of a patient in the CICU who had been admitted for at least two weeks to ensure the optimization of care and to prepare for a subsequent family meeting to discuss the patient’s status with the family. Each meeting was facilitated by a designated CICU physician who might or might not have cared for the patient previously. Here we report on the pre—family meeting huddle, alone; discussion of the subsequent family meetings is reported elsewhere.12

Procedure and Tools

Ten interprofessional team pre—family meeting huddles were audio-recorded. Audio recordings were coded using NVivo 11 (QSR International, released 2015, Melbourne, Australia). Coding attributed all clearly spoken utterances to the individuals who had spoken them. This attribution was used to calculate the percentage of each meeting that members of each profession spoke because it allowed us to determine the actual duration of each speaker’s contributions. Periods of silence and periods during which multiple providers spoke at the same time were also included in the time denominator of each meeting’s analysis—as such, we note that speaking percentages do not add to 100%.

After training, two coders used the Performance Assessment of Communication and Teamwork Novice Observer form (PACT-Novice),13 to assess team performance by listening again to the meeting recordings. The PACT-Novice tool evaluates the domains of team structure, leadership, situation monitoring, mutual support, and communication on a five-point scale (1 = poor; 3 = average; 5 = excellent). We slightly adapted only one of the domains (situation monitoring was changed from “includes patient/family in communication” to “includes patient/family concerns”) to better reflect the nature of the team preparation meeting, which did not include patients or family members. We used the novice version of this tool, as recommended by the developers of PACT-Novice, because our coders did not have previous experience with the TeamSTEPPS framework.14 Team-STEPPS, a resource developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense (DoD), stands for “Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety,” and has five key principles or skill domains: team structure, leadership, situation monitoring, mutual support, and communication.15 Once during coding and again after all coding was complete, the coders met to discuss and resolve any discrepancies.

An electronic survey was sent to meeting participants immediately after each meeting. Surveys collected demographic items including gender, race, and ethnicity; clinical characteristics such as professional discipline, years of experience, and average number of family meetings attended by the participant per week; and the Collaboration and Satisfaction About Care Decisions questionnaire, which measures perception of collaboration and satisfaction with the collaboration process.16 Scores for perceived collaboration range from 7 to 49 (with seven individual items on a scale from 1 to 7) and scores for satisfaction with collaboration range from 1 to 7, with higher scores reflecting an increased amount of perceived collaboration or satisfaction.

Statistical Analysis for Identifying Predictors of Meeting Concordance

To measure each participant’s perception of collaboration at a given meeting, we created a summation of the seven Collaboration and Satisfaction About Care Decisions16 items that relate to collaboration. To determine whether each meeting could be classified as concordant or discordant, we used a mixed-effects linear regression with a random intercept for each subject and tested whether the average collaboration score was significantly different across physician and nonphysician respondents for each meeting. We used a bootstrapping approach to generate 999 random samples of the data with replacement and added those samples to our original sample so that we could run our mixed-effects linear regression on the 1000 samples to get reliable estimates standard errors with a small sample. Using the distribution of 1000 samples, we determined whether the average collaboration score was significantly different between physicians and nonphysicians at each meeting using an alpha of 0.05. Meetings in which collaboration scores were found to be significantly different across groups were classified as discordant. Results were analyzed using SAS software (version 9.4; Copyright 2014, SAS Institute Inc., Chesterbrook, PA).

Using the meeting-level classification of discordance or concordance as our outcome, we examined whether the level of participant characteristics at each meeting was associated with the meeting classification. We ran a separate meeting-level univariable logistic regression for each participant characteristic. Characteristics included percent of respondents at the meeting who were members of the cardiac team; white; physicians; and female.

Results

The overall survey response rate per meeting varied from 50% to 88.9%, with a mean of 61.9% (SD: 12%). The physician response rate averaged 54% across the 10 meetings (range: 25%—83%; SD: 16%), whereas the nonphysician rate averaged 77% (range: 40% —100%; SD:23%). Seventy-one surveys were completed by 38 respondents. One respondent completed seven surveys; two completed six surveys; one completed five surveys; one completed four surveys; two completed three surveys; six completed two surveys; and 25 completed one survey.

Participants

Fifty different members of the hospital staff attended at least one of the 10 CICU team meetings studied. Three staff members attended seven meetings; one attended six meetings; five attended five meetings; four attended four meetings; four attended three meetings; six attended two meetings; and 27 attended one meeting. Because participation was not mandatory, other than the physician leading the meeting, there was no required composition of team members for the meeting to proceed. The number of attendees per meeting averaged 11.5 (range: 8—16; SD: 2.6). An average of 1.1 attendees per meeting were from outside the CICU/cardiac units (range: 0—4; SD: 1.5). The noncardiac providers included a transplant team member; an immunology team member; a palliative care nurse practitioner; a neurologist; a neonatologist; and a pulmonologist. Attendees overall were predominantly female (76%); there were equal numbers of men and women physician attendees, while all the nonphysician attendees were women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Professional Characteristics of Participants

| Participant Characteristics | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Attending intensivist | 7 (18) |

| Cardiologist | 1 (3) |

| Cardiac surgeon | 0 |

| Cardiac fellow | 3 (8) |

| Physical therapist | 2 (5) |

| Occupational therapist | 2 (5) |

| Subspecialist or consulting fellow | 2 (5) |

| Subspecialist or consulting attending | 4 (11) |

| Nurse practitioner | 6 (16) |

| Nurse manager | 3 (8) |

| Bedside nurse | 3 (8) |

| Child life specialist | 1 (3) |

| Social worker | 4 (11) |

| Missing | 12 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 38 (76) |

| Male | 12 (24) |

| Race | |

| White | 28 (74) |

| Black or African American | 3 (8) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 |

| Asian | 5 (13) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Other (“South Asian American,” “multiple races”) | 2 (5) |

| Missing | 12 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1 (3) |

| Non-Hispanic | 37 (97) |

| Missing | 12 |

| Years working in field | |

| 1 or less | 3 (8) |

| 2—5 yrs | 17 (45) |

| 6—10 yrs | 7 (18) |

| >10 yrs | 11 (29) |

| Missing | 12 |

| Average number of family meetings attended per week (as estimated by subjects) | |

| None | 11 (29) |

| 1 | 19 (50) |

| 2—4 | 8 (21) |

| 5 or more | 0 |

| Missing | 12 |

Meeting Characteristics

The meetings had a mean duration of 40.1 minutes (range: 31 to 51.3; SD: 7.39). All meetings were led by a CICU attending physician who began the meeting with a summary of the clinical course and current status of the patient. Seven different CICU attendings led the meetings: three led two meetings, whereas four attendings led one meeting. The meetings were typically held immediately before a family conference during which the attending would speak with the patient’s family. At each team meeting, there was discussion of both the patient’s medical condition and psychosocial issues.

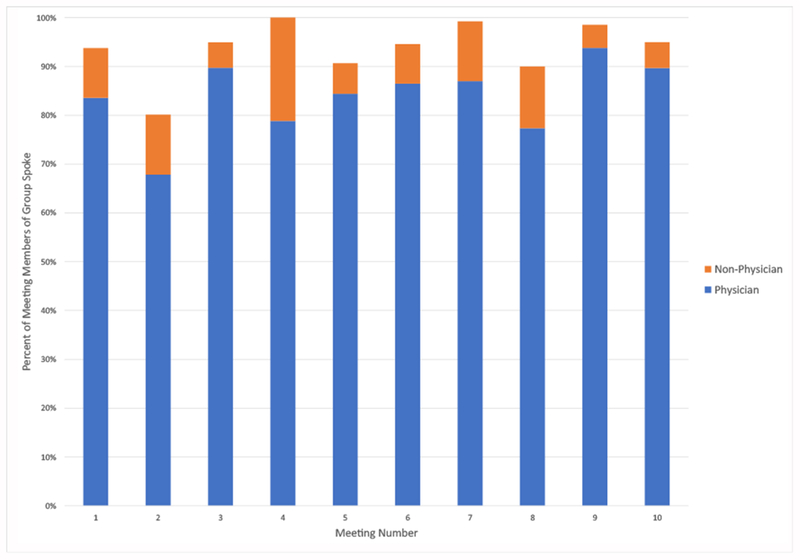

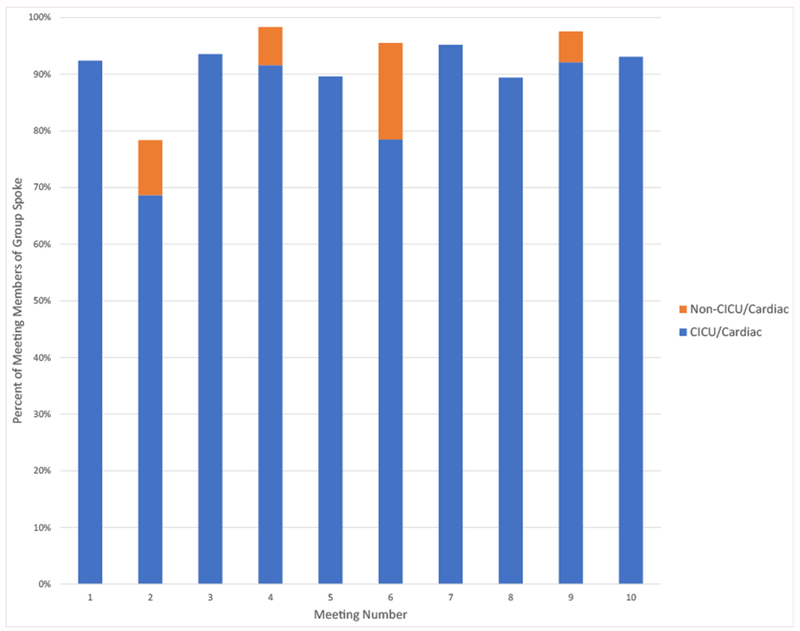

Comparison of Speaking Time by Profession

Physicians dominated the speaking time (Fig. 1), speaking for an average of 83.9% of each meeting (range: 53.24%—89.94%; SD: 7.5%). Nonphysicians spoke for an average of 9.9% of each meeting (range: 0.68%—21.17%; SD: 5.2%). Cardiac/CICU staff spoke for an average of 88.4% of each meeting (range: 52.87%—95.6%; SD: 8.3%). Noncardiac/CICU staff spoke for an average of 3.9% of each meeting (range: 0%—36.59%; SD: 5.9%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Physician versus nonphysician speaking percentage by meeting.

Fig. 2.

Cardiac/CICU versus noncardiac/CICU speaking percentage by meeting. CICU = cardiac intensive care unit.

Team Performance

Across the 10 meetings, PACT-Novice scores were a mean of 3 out of a possible 5 for team structure (range: 3; SD: 0); 2.7 for leadership (range: 2—4; SD: 0.8); 3 for situation monitoring (range: 3; SD: 0); 3.2 for mutual support (range: 2—4; SD: 0.6); and 2.8 for communication (range: 2—3; SD: 0.4). Quotes that illustrate group behaviors matching the five TeamSTEPPS skill domains can be found in Table 2. All scores fell within the “average” range, which, in the PACT-Novice tool, qualitatively means that “most behaviors were present and adequately performed” but that they did not meet the next higher standard between average and excellent.17 An excellent score would indicate that “all critical behaviors are present and performed well.”

Table 2.

PACT-Novice TeamSTEPPS Skill Domains and Exemplary Quotes

| Skill Domain | Behaviors | Exemplary Quote(s) for Selected Behaviors |

|---|---|---|

| Team structure | Identifies goals, assigns roles and responsibilities, holds members accountable | “I think at our update, just showing [the family] that he’s not making progress on coming off the ventilator, […] and the thing that will probably get him home quickest would be to proceed with tracheostomy.” (physician leading meeting—identifies goals) |

| Leadership | Utilizes resources; delegates tasks and balances workload; conducts briefs, huddles, and debriefs; empowers members to speak freely | “And please correct me if I’m mistaken because I’m just going by what was reported to me.” (physician leading meeting—empowers members to speak freely) |

| Situation monitoring | Includes patient/family concerns, cross monitors members and applies the STEP process, fosters communication | “And the parents are very interested, I think that their main concern after the cardiac arrest was neuro injury.” (physician leading meeting—includes patient/family concerns) |

| Mutual support | Advocates for the patient resolve conflict using two-challenge rule, CUS and DESC script, works collaboratively | “Can you just show his EKG as well?” (physician leading meeting to physician running chart display—works collaboratively) |

| Communication | Provides brief, clear, specific, and timely information; seeks and communicates information from all available sources; uses SBAR, callouts, check-backs, and handoff techniques | “Uh, Cefotaxime.” (physician leading meeting) “Cefotaxime.” (Fellow) “Yeah, cefotaxime.” (physician leading meeting—uses check-backs) |

Perceptions of Collaboration and Satisfaction With Decision Making

In the 10 meetings, the average score for perception of collaboration was 38.7 out of a possible 49 (SD: 3.5). Average score for satisfaction with collaboration was 5.8 out of a possible 7 (SD: 0.4). In three of 10 meetings, physician and nonphysician perceptions were found to be significantly discordant from one another (Table 3). In two of the three discordant sessions, physicians perceived the session to be more collaborative than nonphysicians.

Table 3.

Physician Versus Nonphysician Mean Collaboration and Satisfaction Scores by Meeting

| Meeting | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration scores (range: 7—49) | ||||||||||

| Physician | 40.0 | 41.8 | 37.0 | 42.0 | 41.3 | 43.8 | 41.8 | 41.5 | 37.8 | 46.7 |

| Nonphysician | 39.7 | 24.3 | 37.8 | 37.9 | 32.4 | 30.7 | 28.0 | 49.0 | 33.3 | 40.3 |

| Satisfaction with collaboration scores (range: 1—7) | ||||||||||

| Physician | 5.5 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 6.7 |

| Nonphysician | 6.0 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

Bold values indicate meetings where statistically significant differences were found between physician and nonphysician scores.

Predictors of Concordance

Logistic regression did not identify any significant predictors of discordance versus concordance when looking at demographic composition of the meetings or meeting characteristics.

Discussion

Interprofessional team huddles before family meetings are critically important processes that ensure team members are equipped with a shared understanding of the patient and their treatment plan options to provide consistent messaging to the family. In this study, we found that team members with different professional roles behaved differently in the prefamily meeting team huddles. Indeed, physicians (who led the discussion) spoke for the majority of the time, and team members from outside the CICU made the fewest contributions. Despite these imbalances, the CICU’s teamwork was, on average, effective. However, there were statistically significant differences between physicians’ and nonphysicians’ perceptions of team collaboration in three of the 10 observed meetings. These findings suggest that, although the teamwork was effective, there is room for improvement in interprofessional team dynamics.

The finding that physicians spoke at greater length than nonphysicians can be interpreted as physician dominance of the meeting because participant speaking length has been shown to function as a good baseline measure of dominance in meetings.18 Moreover, our findings are consistent with other qualitative research studies in the literature, which reveal similar patterns of physician dominance during team discussions.19,20 For example, in an examination of medical dominance in multidisciplinary team discussions about discharge decision making, physicians who chaired meetings exercised disproportionate power and influence.20 These findings underscore the hierarchical relationship of interprofessional teams, wherein physicians, serving as the ultimate decisionmaking authority, routinely assume the role of leader in discussions that include a review of medical information. But in assessing team performance, the extent to which the physician leader engages team members and incorporates their input in a meeting may be more important in evaluating teamwork than team leader speaking dominance.21 For example, a qualitative analysis of interdisciplinary team meetings in a long-term care facility found that a central element of team communication included a “collaborative” aspect of the conversation, wherein the leader engaged other nonphysician team members about their understanding of and concerns about the patient’s care plan.22

Despite the verbal dominance by the physician leader, our analysis of teamwork using a validated instrument found that team performance was average in all five skill domains.23 This level of performance may be the result of shared norms of communication by the core group of CICU team members who consistently attended the meetings. A stable team that is able to build mutual respect and develop a shared mental model for the purpose of the meeting is more likely to be successful in working collaboratively and respectfully during problem solving.24 In addition, concurrent quality improvement initiatives taking place in the CICU during our observation phase may have helped drive team performance outcomes, as quality improvement work may encourage team member psychological safety and may discourage behaviors of hostility/disengagement,21 thus improving team performance.

However, despite the adequate teamwork scores, there was significant discordance in perception of team collaboration between physician and nonphysician respondents in three of the 10 meetings we observed. And in two of these three instances, nonphysician respondents perceived the team meeting as less collaborative than physicians. These data are consistent with prior research showing that critical care physicians tend to perceive a more collaborative environment than nursing staff.25 This same trend has also been demonstrated with nursing and physician staff in surgical ICUs26; inpatient surgical wards27; and medical/surgical ICUs.28

The significant discordance observed between provider types suggests that physicians may be unaware of both their behaviors and the impact of these behaviors on nonphysicians’ experiences. How individual CICU attendings lead the meetings and request information from other professionals can, wittingly or not, invalidate others’ contributions, leading interprofessional team members in less powerful positions to feel intimidated or silenced.29 Moreover, studies in management literature have demonstrated that underutilizing the contributions of skilled workers can negatively impact job satisfaction30; innovation31; and productivity.32 Conversely, when done well, collaborative leadership behaviors can promote an overall sense of leader inclusiveness—the perception of leaders as welcoming and inclusive of the ideas and work of others.21 Leader inclusiveness may positively impact nonphysicians’ psychological safety, while eliciting the views of nonphysicians may allow physicians to learn more from a group discussion. Along these lines, further research is needed to examine teamwork variations and better understand both how physicians elicit nonphysicians’ opinions and how this process impacts perceptions of team collaboration.

The study has a number of limitations due to the fact that it was a small, single-institution study. Although the response rate was well within the range of acceptability for a survey of medical professionals, 12 meeting attendees did not fill out a postmeeting survey, which constrains interpretation of the collaboration tool. The present findings may not be generalizable to other meetings in other units or hospitals, despite the fact that these results resonate with our anecdotal experience at other institutions. Finally, the use of audio recording limits the scope of our analysis to communication expressed solely through audible speech; other nonverbal communication may have been missed and should be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

Members of different professions behave differently in team meetings, with our study revealing findings of physician dominance in observed interprofessional meetings in our institution’s CICU. While outside observers of these meetings felt that the teamwork was adequately effective, there were significant differences in the perception of collaboration between physicians and nonphysicians. This first characterization of interprofessional team members’ interactions in team meetings provides important information for other interprofessional teams interested in improving collaboration and communication in team meetings.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Cambia Foundation Sojourns Scholar Award and the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL141700. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Owing to the inability to adequately deidentify these study data, the data will not be publicly available.

The study received institutional ethics approval from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greiner AC, Knebel E. Institute of medicine Committee on the health professions Education Summit Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriquez J Who is on the medical team?: shifting the boundaries of belonging on the ICU. Social Sci Med 2015; 144:112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosser G, Begun J. Understanding teamwork in health care. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fineberg IC, Kawashima M, Asch SM. Communication with families facing life-threatening illness: a research-based model for family conferences. J Palliat Med 2011;14: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, et al. The impact of rudeness on medical team performance: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2015;136:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nembhard IM, Singer SJ, Shortell SM, Rittenhouse D, Casalino LP. The cultural complexity of medical groups. Health Care Manag Rev 2012;37:200–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penson RT, Kyriakou H, Zuckerman D, Chabner BA, Lynch TJ. Teams: communication in multidisciplinary care. The Oncologist 2006;11:520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris KT, Treanor CM, Salisbury ML . Improving patient safety with team coordination: challenges and strategies of implementation. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006;35: 557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panel IECE. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter JK, Sachs E, Schall TE, et al. Interprofessional teamwork during family meetings in the pediatric cardiac intensive care Unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. United States 2019. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.002. pii: S0885–3924(19)30112–30115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu C-J. Development and validation of performance assessment tools for interprofessional communication and teamwork (PACT). University of Washington, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotz ME, Dueñas GG, Zanoni A, Grover AB. Designing and evaluating an interprofessional experiential course series involving medical and pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ 2016;80:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clancy CM, Tornberg DN. TeamSTEPPS: assuring optimal teamwork in clinical settings. Am J Med Qual 2007;22:214–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baggs Gedney J. Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. J Adv Nurs 1994;20:176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiu CJ, Brock D, Abu-Rish E, et al. Performance Assessment of Communication and Teamwork (PACT) Tool Set. Available from https://collaborate.uw.edu/pact_tool_set/. Accessed April 28, 2019.

- 18.Hung H, Jayagopi DB, Yeo C, et al. Using audio and video features to classify the most dominant person in a group meeting. MM ‘07 Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Multimedia Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany: IDIAP, 2007:835–838. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lingard L, Vanstone M, Durrant M, et al. Conflicting messages: examining the dynamics of leadership on interprofessional teams. Acad Med 2012;87:1762–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gair G, Hartery T. Medical dominance in multidisciplinary teamwork: a case study of discharge decisionmaking in a geriatric assessment unit. J Nurs Management 2001;9:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organizational Behav 2006;27:941–966. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bokhour BG. Communication in interdisciplinary team meetings: what are we talking about? J Interprof Care 2006;20:349–363. England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer-Jackman KL, Sabata D, Gibbs H, et al. Creating an online interprofessional collaborative team simulation to Overcome Common Barriers of interprofessional education. Int J Health Professions 2017;4:90–99. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker DP, Day R, Salas E. Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res 2006;41(4 Pt 2):1576–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sollami A, Caricati L, Sarli L. Nurse-physician collaboration: a meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprofessional Care 2015;29:223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, Eldredge DH, Oakes D, Hutson AD. Nurse-physician collaboration and satisfaction with the decision-making process in three critical care units. Am J Crit Care 1997;6:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxson PM, Dozois EJ, Holubar SD, et al. Enhancing nurse and physician collaboration in clinical decision making through high-fidelity interdisciplinary simulation training. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nathanson BH, Henneman EA, Blonaisz ER, Doubleday ND, Lusardi P, Jodka PG. How much teamwork exists between nurses and junior doctors in the intensive care unit? J Adv Nurs 2011;67:1817–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown J, Lewis L, Ellis K, Stewart M, Freeman TR, Kasperski MJ. Conflict on interprofessional primary health care teams-can it be resolved? J Interprofessional Care 2011;25:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchanan J, Finegold D, Mayhew K, Warhurst C, Livingston DW. Skill under-utilization. Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Länsisalmi H, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M. Is underutilization of knowledge, skills, and abilities a major barrier to innovation? Psychol Rep 2004;94:739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen J, Van der Velden R. Educational mismatches versus skill mismatches: effects on wages, job satisfaction, and on-the-job search. Oxford Econ Pap 2001;53:434–452. [Google Scholar]