The use of messenger RNA (mRNA) therapy by systemic delivery to treat metabolic disorders has long been hampered by poor stability, immunogenicity, inefficient delivery, and hepatic toxicity. In contrast, other molecular therapies such as viral gene and enzyme replacement therapy (Fig. 1) have been effectively employed to successfully treat rare metabolic diseases in both animals and humans. However, viral gene therapy is not without concerns of genotoxicity, transgene persistence, packaging constraints, production scalability, and preexisting immunity to the viral capsid (1). Similarly, enzyme replacement therapy can be difficult to deliver to some tissues and cellular compartments, and immune responses to the enzyme can occur (2). Advancements in lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-mediated mRNA therapy have greatly improved the ability to systemically deliver mRNA to the liver and to express high levels of protein coded by the therapeutic mRNA (3). The greatest remaining concern surrounding LNP-mRNA therapy is that it supplies only a short period of transgene expression in comparison to other therapies, but transgene expression from an LNP-mRNA vector can be extended with repetitive treatment. This emerging therapeutic option for genetic diseases has been used to treat a small but growing number of murine models of metabolic disorders (4–7). A report in PNAS by Truong et al. (8) examines the use of LNP-mRNA therapy to treat arginase deficiency (AD) and illustrates how LNP-mRNA therapy might be used to effectively treat this disease as well as other metabolic diseases of the liver.

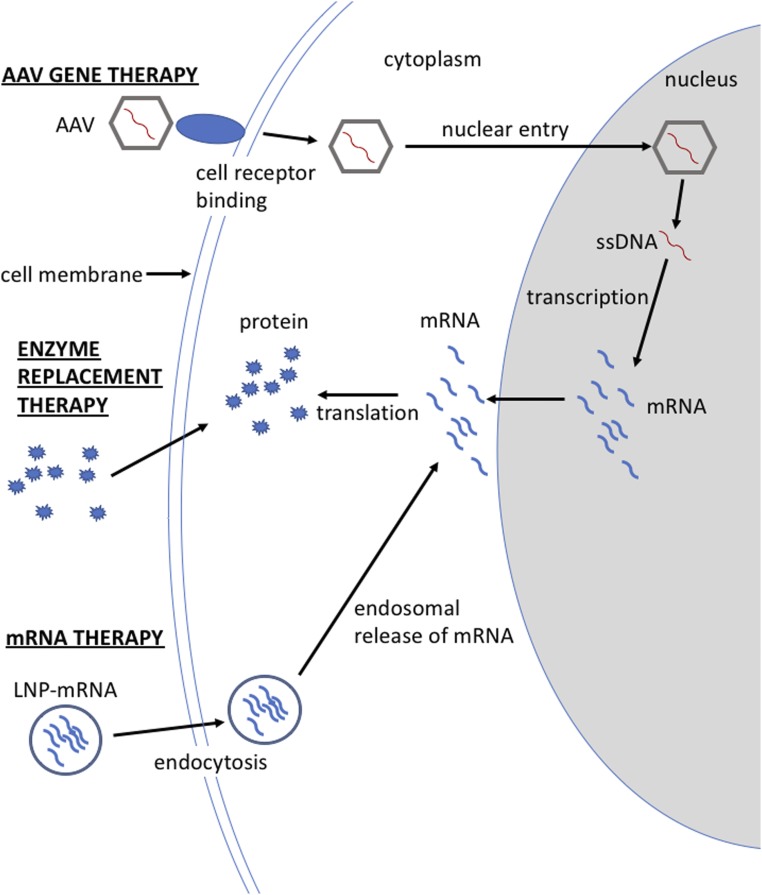

Fig. 1.

Cellular entry and processing of different molecular therapies. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) uses receptor binding to gain cell entry. The AAV needs to traffic to the nucleus for the AAV’s single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to be converted to double-stranded DNA and transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), which is then exported from the nucleus and translated to protein. Enzyme replacement therapy delivers the therapeutic protein, which only needs to gain entry into the cell. Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) mRNA gains entry to the cell by endocytosis where it can be translated to protein. The therapeutic protein delivered by any of these molecular therapies may require entry into a cellular organelle or secretion from the cell if the protein function is location dependent.

AD is an autosomal recessive metabolic disease caused by mutations in the arginase (ARG1) gene (9). ARG1 catalyzes the final step in the urea cycle, a metabolic pathway, which occurs primarily in the liver and is responsible for the conversion of highly toxic ammonia to urea for excretion. Clinically, patients with AD can suffer from microcephaly, seizures, loss ambulation, clonus, spastic diplegia, intellectual disability, growth retardation, and lethality. Biochemically, deficient ARG1 enzyme activity results in elevated levels of arginine and guanidino compounds in patients, which are hypothesized to be neurotoxic. Hyperammonemia can occur in AD, but this serious complication is less frequent than in other urea cycle disorders. Treatment for AD includes a protein-restricted diet, amino acid supplementation, and the administration of the nitrogen scavengers with the goal of reducing arginine and guanidino compounds levels. Liver transplantation has been explored as a treatment option for AD in 2 patients. Long-term follow-up of these patients has found that they had normal plasma arginine levels and did not suffer from the progressive neurological decline normally observed in patients with AD. These results highlight the importance of the liver as a target of any molecular therapy. Unfortunately, even when receiving the current standard of care, AD patients still suffer from a progressive neurological phenotype, which underscores the need to develop new treatments.

Multiple molecular therapies have been studied in murine models of AD. Preclinical studies of enzyme replacement showed that treated mice had lower plasma arginine levels, but treatment did not rescue the mice from death (10). In contrast, studies have demonstrated that the adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy is capable of treating a murine model of AD (11). However, many patients will likely have preexisting antibodies to AAV capsid proteins, which would make these patients unresponsive to AAV gene therapy. In addition, treatment of patients early in life when cells are rapidly dividing will lead to a rapid dilution of episomal AAV transgene. Alternative treatments will be needed for patients with preexisting neutralizing antibodies and for the treatment of patients early in life. The LNPs currently being used for mRNA therapy have been designed to have lower immunogenicity than its predecessors, and unlike AAV vectors, LNP-mRNA can be redosed. LNP-mediated delivery of ARG1 mRNA was previously explored in wild-type mice and demonstrated efficient delivery of ARG1 mRNA to the liver and hepatic ARG1 expression (12). However, this study did not address the question of phenotypic or biochemical correction of the AD mice.

This important question is addressed by Truong et al. (8) in PNAS. Prior to testing ARG1 mRNA treatment in AD mice, they delivered a systemic dose of 2 mg/kg LNP-firefly luciferase (LNP-luc) reporter mRNA to wild-type mice and demonstrated their vector had efficient liver targeting, transgene expression, and the ability to be effectively readministered. Luciferase protein expression was first detected at 2 h postinjection and was detectable for as long as 36 h postinjection in some treated animals.

Next, a biodegradable liver LNP encapsulating a codon-optimized ARG1 mRNA (LNP-ARG1) was used to treat wild-type mice at a dose of 2 mg/kg to determine the pharmacokinetics of the particle. The levels of ARG1 mRNA in the livers of treated mice were determined by quantitative real-time PCR using probes specific to the codon-optimized ARG1 mRNA and normalized to the housekeeping gene Gapdh. ARG1 mRNA peaked at 2 h posttreatment (1.49 × 105 ± 2.06 × 104 relative transcript levels), diminished to 4.4% of the peak levels at 24 h posttreatment, and remained stable at 0.25% of peak levels from 2 to 7 d posttreatment.

Truong et al.’s final set of studies examined the ability of their LNP-ARG1 to treat a conditional murine model of ARG1 deficiency (Arg1flox/flox). To induce ARG1 deficiency, adult Arg1flox/flox mice were treated with AAV8-expressing Cre recombinase using a liver-specific promoter to excise 2 critical exons from the murine Arg1 gene. Groups of adult Arg1flox/flox mice were treated at day 14 post-Arg1 disruption with an LNP-ARG1 or LNP-luc (negative control). Treatment groups either received a systemic repetitive (dosing every 3 d or 1 wk) dose regime of 2 mg/kg LNP-ARG1 or LNP-luc. Both groups of LNP-ARG1–treated AD mice exhibited a significantly increased survival rate in comparison to the groups of LNP-luc–treated mice, but the weekly LNP-ARG1–treated group suffered weight loss and none survived longer than 62 d. By contrast, all of the AD mice treated every 3 d with LNP-ARG1 survived for 77 d (the length of the study) and maintained their body weight.

The AD mice experience a persistent hyperammonemia, which is likely the cause of death in these mice. Interestingly, hyperammonemia in patients with ARG1 deficiency is less common than in other urea cycle disorders and it results in a severer phenotype in AD mice than that observed in AD humans. Both groups of the LNP-luc treated and the weekly LNP-ARG1 treated displayed elevated plasma ammonia levels throughout the study. However, the AD mice treated with LNP-ARG1 at 3-d intervals had wild-type plasma ammonia levels and displayed normal nitrogen metabolism to urea. Importantly, this group of LNP-ARG1–treated mice had normal plasma and hepatic levels of arginine and guanidinoacetic acid, which are suspected neurotoxins of this diseases, as well as normal plasma and hepatic levels of glutamine, ornithine, and lysine.

These studies demonstrated that repetitive delivery of LNP-ARG1 can achieve high levels of enzymatically active ARG1 expression in the liver without signs of toxicity. Histological examination of livers from the mice repeatedly treated with the LNP revealed no abnormalities: Specifically, no signs of inflammation, fibrosis, or subcellular injury were observed. Furthermore, alanine aminotransferase plasma levels, a biomarker of liver injury, was normal in the LNP-ARG1–treated mice.

In summary, the authors found that repetitive (3-d increments) LNP-ARG1 treatment of AD mice rescues lethality, prevents weight loss, and corrects biomarkers of this disease without signs of hepatic toxicity. This study adds LNP-mRNA therapy to the list of molecular therapies, which includes viral-mediated gene and enzyme replacement therapy, that have been tested in murine models of ARG1 deficiency. While no one molecular therapy is likely to be ideal for all patients, LNP-mRNA could, for example, be an alternative to gene therapy for patients with preexisting viral antibodies, assuming a gene therapy treatment already existed. These and other studies lend hope that one day patients with genetic disease and the physicians treating them will have multiple molecular therapies available to them, rather than the limited and often suboptimal treatment options that currently exist for most inherited metabolic diseases.

Acknowledgments

The author’s research is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Intramural Research Program of the NIH.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

See companion article on page 21150.

References

- 1.Chandler R. J., Venditti C. P., Gene therapy for metabolic diseases. Transl. Sci. Rare Dis. 1, 73–89 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohashi T., Enzyme replacement therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 10 (Suppl 1), 26–34 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martini P. G. V., Guey L. T., A new era for rare genetic diseases: Messenger RNA therapy. Hum. Gene Ther., 10.1089/hum.2019.090 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao J., et al. , mRNA therapy improves metabolic and behavioral abnormalities in a murine model of citrin deficiency. Mol. Ther. 27, 1242–1251 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prieve M. G., et al. , Targeted mRNA therapy for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Mol. Ther. 26, 801–813 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang L., et al. , Systemic messenger RNA as an etiological treatment for acute intermittent porphyria. Nat. Med. 24, 1899–1909 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An D., et al. , Systemic messenger RNA therapy as a treatment for methylmalonic acidemia. Cell Reports 21, 3548–3558 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truong B., et al. Lipid nanoparticle-targeted mRNA therapy as a treatment for the inherited metabolic liver disorder arginase deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 21150–21159 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong D., Cederbaum S., Crombez E. A., “Arginase deficiency” in GeneReviews, Adam M. P., et al., Eds. (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrage L. C., et al. ; Members of Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium , Human recombinant arginase enzyme reduces plasma arginine in mouse models of arginase deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 6417–6427 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee E. K., et al. , Long-term survival of the juvenile lethal arginase-deficient mouse with AAV gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 20, 1844–1851 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asrani K. H., Cheng L., Cheng C. J., Subramanian R. R., Arginase I mRNA therapy—a novel approach to rescue arginase 1 enzyme deficiency. RNA Biol. 15, 914–922 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]