Abstract

Animals perform or terminate particular behaviors by integrating external cues and internal states through neural circuits. Identifying neural substrates and their molecular modulators promoting or inhibiting animal behaviors are key steps to understand how neural circuits control behaviors. Here, we identify the Cholecystokinin-like peptide Drosulfakinin (DSK) that functions at single-neuron resolution to suppress male sexual behavior in Drosophila. We found that Dsk neurons physiologically interact with male-specific P1 neurons, part of a command center for male sexual behaviors, and function oppositely to regulate multiple arousal-related behaviors including sex, sleep and spontaneous walking. We further found that the DSK-2 peptide functions through its receptor CCKLR-17D3 to suppress sexual behaviors in flies. Such a neuropeptide circuit largely overlaps with the fruitless-expressing neural circuit that governs most aspects of male sexual behaviors. Thus DSK/CCKLR signaling in the sex circuitry functions antagonistically with P1 neurons to balance arousal levels and modulate sexual behaviors.

Subject terms: Genetics, Neuroscience

P1 neurons integrate sensory cues to initiate male courtship in Drosophila. Here the authors identified inhibitory Drosulfakinin-expressing neurons that interact with P1 neurons in an experience-dependent manner, and oppositely regulate male sex drive.

Introduction

Animal behaviors are modulated by both internal states and external stimuli. When an organism is faced with more than one stimulus in the context of distinct behavioral states, multiple decision-making processes are involved in making appropriate behavioral choices. A fundamental question in neuroscience is to understand how neural circuits and molecular modulators control these decision-making processes. Significant progress has been made in identifying the molecules and neurons that control innate and social behaviors, such as courtship, sleep, feeding, and aggression in Drosophila1–5 and mouse6–9.

Male courtship in Drosophila melanogaster is one of the best-understood innate behaviors, and largely controlled by the fruitless (fru) gene and doublesex (dsx) gene, which encode sex-specific transcription factors (FRUM and DSXM in males and DSXF in females)10–12. FRUM is responsible for most aspects of male courtship13–15, and DSXM is important for the experience-dependent acquisition of courtship in the absence of FRUM, and courtship intensity and sine song production in the presence of FRUM 16,17. FRUM is expressed in a dispersed subset of ca. 2000 neurons including sensory neurons, interneurons, and motor neurons that are potentially interconnected to form a sex circuitry controlling sexual behaviors14,15,18,19. In contrast, DSXM is expressed in ca. 700 neurons in males, the majority of which also express FRUM, and are crucial for male courtship20,21. Recently, substantial progress has been made into how external sensory cues are perceived and integrated by fruM and/or dsxM neurons to initiate male courtship, in particular, how a subset of male-specific fruM- and dsxM-expressing P1 neurons integrate olfactory and gustatory cues from female or male targets to initiate or terminate courtship22–26. Such a neuronal pathway is also conserved in other Drosophila species27–29.

Behavioral decisions depend on both excitatory and inhibitory modulations. P1 neurons represent an excitatory center that integrates multiple (both excitatory and inhibitory) sensory cues and initiates courtship4,24,25. However, whether there is an inhibitory counterpart that operates against P1 neurons to balance sexual activity is still unknown. Indeed, males do not absolutely court virgin females even if these females may provide the same visual, olfactory, and gustatory cues, depending on the male’s internal states and past experiences. It has been previously shown that neuropeptide SIFamide acts on fruM-positive neurons and inhibits male–male but not male–female courtship30,31, and SIFamide neurons also integrate multiple peptidergic neurons to orchestrate feeding behaviors32, but whether SIFamide inhibits internal arousal states for sexual behaviors is not clear. Recently, we found that sleep and sex circuitries interact mutually and demonstrate how DN1 neurons in the sleep circuitry and P1 neurons in the courtship circuitry function together to coordinate behavioral choices between sleep and sex33. However, we know very little on the inhibitory pathway(s) that may represent internal arousal states and inhibit courtship toward females.

In this study, we set out to identify courtship inhibitory neurons that express neuropeptides in Drosophila, as neuropeptides play key roles in adjusting animal behaviors based on environmental cues and internal needs34,35. We identify the neuropeptide Drosulfakinin (DSK), the fly ortholog of Cholecystokinin (CCK) in mammals, functions through its receptor CCKLR-17D3 in the fruM-expressing sex circuitry to inhibit male courtship toward females. We further demonstrate that Dsk neurons and P1 neurons interact and oppositely regulate male sexual behaviors.

Results

Drosulfakinin-GAL4 neurons inhibit male courtship behavior

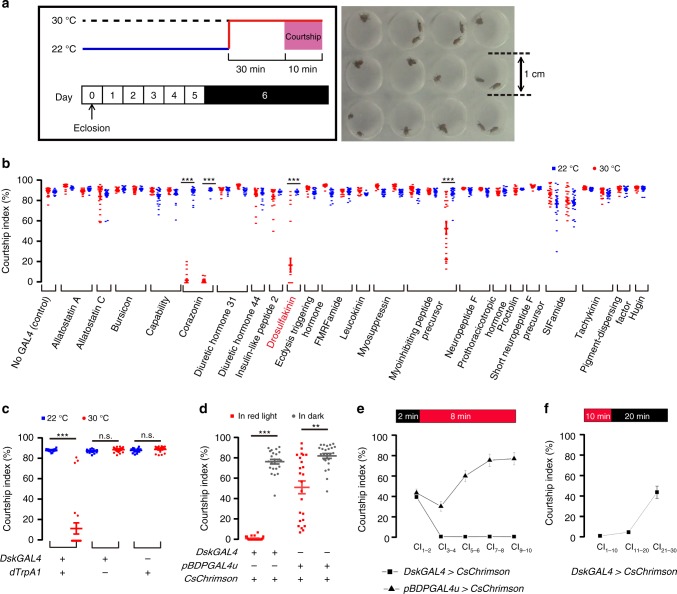

We speculated that neuropeptides might function as molecular modulators in courtship circuit to control courtship behaviors, and screened for courtship deficit using 32 GAL4 lines driving the temperature-sensitive activator dTrpA136 in distinct subsets of peptidergic neurons37,38 (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Identification of DskGAL4 neurons that inhibit male courtship. a Experimental design of screening for courtship-inhibiting neurons. b Identification of DskGAL4 and CrzGAL4 that inhibit male courtship when driving UAS-dTrpA1 at 30 °C (red circle) compared to permissive temperature 22 °C (blue square). n = 12 for sNPF-GAL4 and Lk-GAL4, n = 18 for Burs-GAL4, Dh31-GAL4 and Proc-GAL4, n = 20 for SIFaGAL4s, n = 24 for others. ***p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test. c Thermogenetic activation of Dsk neurons labeled by another DskGAL4 (attP2) severely inhibits male courtship. n = 24 for each. p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.1 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. d Optogenetic activation of DskGAL4 (attP2) neurons abolishes male courtship. n = 24 for each. p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001, post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. e Optogenetic activation of DskGAL4 neurons rapidly inhibits male courtship. n = 24 for each. f Courtship inhibition by optogenetic activation of DskGAL4 neurons lasts for more than 10 min after lights off. n = 24. n.s. not significant. Error bars indicate SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

This screen identified three GAL4 lines when combined with UAS-dTrpA1 at 30 °C severely impaired male courtship, including two Corazonin (Crz) GAL4 lines and a Drosulfakinin (Dsk) GAL4 line (courtship index [CI] < 20%, which is the fraction of observation time that males courted, Fig. 1b). Further analysis revealed that activating CrzGAL4 neurons37, but not DskGAL4 neurons, induced rapid ejaculation in isolated males (Supplementary Table 1). We also identified a Myoinhibitory-peptide (Mip) GAL4 line when combined with UAS-dTrpA1 at 30 °C mildly inhibited male courtship (CI~54%), but such inhibition was not consistent using two other Mip-GAL4 drivers (CIs > 80%, Fig. 1b). We also found that activation of neurons labeled by two SIFaGAL4 drivers did not affect male courtship toward females (CIs > 80%, Fig. 1b), although it was previously shown that SIFamide neurons inhibit male–male courtship30,31. Thus, we focused our further study on Dsk and Dsk-expressing neurons.

The above P-element based DskGAL4 labels a subset of Dsk-expressing neurons as well as a few non-Dsk neurons as revealed by GFP and anti-DSK (Supplementary Fig. 1). To further study the function of Dsk-expressing neurons, we generated the PhiC31-based site-specific DskGAL4, DskLexA, and DskFlp, using the 1.1 kb sequence upstream of the transcription start site of the Dsk gene as promoter. The new DskGAL4 specifically labels four pairs of neurons in the medial protocerebrum, and weakly labels a few insulin-producing cells (IPCs) in the Pars Intercerebralis (PI) region (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a), confirming a previous study39. Thus we used the new DskGAL4 hereafter. Activation of these DskGAL4-labeled neurons via dTrpA1 severely impaired male courtship (CI~10%, Fig. 1c, Supplementary Movie 1), while activating the Dsk-positive IPCs using dilp2GAL440 did not affect courtship (CI > 80%, Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, activating DskGAL4 neurons does not affect feeding, probably due to the weak labeling of IPCs (Supplementary Fig. 3). Silencing DskGAL4 neurons does not enhance the already high level of male courtship (CIs > 80%, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

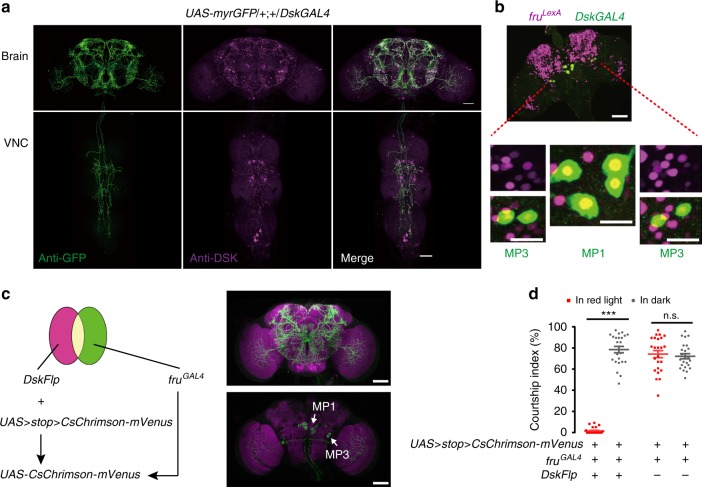

Four pairs of Dsk- and fruM-expressing neurons inhibit male courtship. a Expression pattern of DskGAL4 in the central nervous system revealed by anti-GFP (left) and anti-DSK (middle). Representative of eight male flies. Scale bars, 50 μm. b Two pairs of MP1 and two pairs of MP3 neurons are co-labeled by fruLexA driving LexAop-RedStinger (magenta) and DskGAL4 driving UAS-Stinger-GFP (green). Representative of five male brains. Scale bars, 50 μm and 20 μm (zoom-in). c Intersectional strategy to label and manipulate Dsk and fruM co-expressing MP1 and MP3 neurons. Representative of 6 male brains. Scale bars, 50 μm. d Optogenetic activation of intersectional neurons between DskFlp and fruGAL4 abolishes male courtship. Red square indicates test in red light, and gray circle indicates test in dark. n = 24 for each. p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.99 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Error bars indicate SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To further confirm our findings, we used the optogenetic effector CsChrimson41, which affords greater control over the dynamic range of neuronal activation than dTrpA142, and found that optogenetic stimulation of Dsk neurons in UAS-CsChrimson-mVenus/DskGAL4 males almost abolished courtship such that 90% of males do not initiate courtship (CI~2%), dramatically different from all control males (CIs > 50%, Fig. 1d). Note that the empty GAL4 control flies also showed reduced courtship under red light, which may be due to genetic background and/or red light perturbation, and we used other control lines (e.g. DskGAL4/+) in our later experiments. We next assayed courtship in dark condition for 2 min to allow courtship (CI1–2 ~ 40%), and then turned on red light for optogenetic activation. We found that activation of DskGAL4 neurons immediately abolished courtship by males that already initiated courtship (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, we tested how much time such inhibition would last by assaying courtship in dark after 10 min in red light, and found that courtship was only partially restored after ~20 min (CI1–10 is 1%, CI11–20 is 4.8% and CI21–30 is 43.6%, Fig. 1f). These results indicate that DskGAL4 neurons rapidly and efficiently inhibit male courtship and such inhibition lasts for a few minutes.

Four pairs of Dsk and fruM neurons inhibit male courtship

Analysis of the new DskGAL4 and DskLexA using a myr::GFP reporter revealed similar expression patterns, both of which label a subset of neurons in the brain that were previously identified as Dsk-expressing neurons39, including four pairs of neurons in the medial protocerebrum (two pairs of MP1 and two pairs of MP3 cells), and a few IPCs (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). To further confirm these findings, we generated a polyclonal antibody raised against DSK (antigen: FDDYGHMRF, recognized two DSK peptides, DSK-1 and DSK-2), which faithfully labels MP1 and MP3 cells, and a number of interneurons in both the brain and the ventral nerve cord (Fig. 2a), consistent with previous findings39. It should be mentioned that our DskGAL4 did not label neurons in the VNC. It is possible that those antibody-labeled neurons in the VNC are not Dsk-expressing neurons, but the DSK antibody cross-reacts with other peptides in those neurons (e.g. FMRFamide-related peptides). Alternatively, those neurons in the VNC are indeed Dsk-positive, but the DskGAL4 only labels a part of Dsk-expressing neurons. We observed no gross anatomy difference of Dsk neurons using both anti-GFP and anti-DSK between males and females (Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that these Dsk neurons are not sex-specific. Thus, we also activated DskGAL4 neurons using dTrpA1 (Supplementary Fig. 5b) or CsChrimson (Supplementary Fig. 5c) in females and observed significantly reduced receptivity to courting wild-type males. These results indicate that Dsk-expressing neurons are common in both sexes and suppress male and female sexual behaviors, and we focused on male courtship in this study (but see below for their interaction with sex-specific neurons in both males and females).

Male courtship behavior is governed by neural circuitry comprised of ~2000 fruM-expressing neurons14,15,18,19. We asked if the courtship-inhibition neurons labeled by the DskGAL4 are a part of the fruM circuitry. Double labeling of fruLexA and DskGAL4 neurons (LexAop-RedStinger/UAS-stinger-GFP; fruLexA/DskGAL4) revealed that the four pairs of MP1 and MP3 neurons are all fruM-positive (Fig. 2b). We then used an intersectional strategy23 to visualize overlapped expression between fruLexA and DskGAL4 (UAS > stop > myrGFP/+; LexAop2-FlpL fruLexA/DskGAL4), but only observed stochastic MP1 and MP3 cells. However, we observed consistent expression of MP1 and MP3 cells, as well as a number of IPCs, from intersection of fruGAL4 and DskFlp (Fig. 2c). Further, we activated these overlapped neurons using the above optogenetic effector CsChrimson, and found that these males (UAS > stop > CsChrimson-mVenus/+; fruGAL4/DskFlp) almost do not court (CI ~ 2%) under red light stimulation, while all control males court intensively (CIs > 70%, Fig. 2d). Together with the finding that IPCs are not involved in courtship suppression, these results demonstrate that two pairs of MP1 and two pairs of MP3 cells are Dsk- and fruM-positive and responsible for courtship inhibition.

Single-neuron labeling of the Dsk-expressing MP neurons

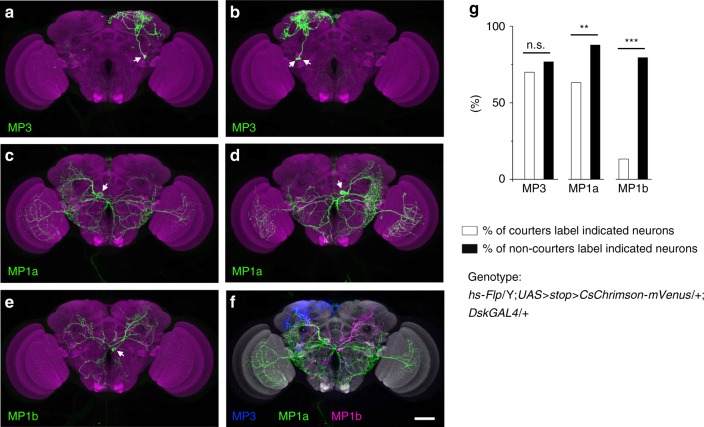

The four pairs of Dsk- and fruM-expressing MP neurons project to various regions of the brain, but the morphology and function of individual neurons or neuronal types are unclear. Thus we used heat-shock controlled flipase to stochastically label and activate subsets of DskGAL4 neurons in males (hs-Flp/Y; UAS > stop > CsChrimson-mVenus/+; DskGAL4/+). These experiments revealed fine structures of individual Dsk neurons. The two pairs of MP3 cells are indistinguishable and mainly project to the superior medial protocerebrum (SMP), the superior lateral protocerebrum (SLP) and the lateral horn (LH)43 (Fig. 3a labels a single MP3 neuron, and Fig. 3b labels two MP3 neurons). The two pairs of MP1 cells are distinct and termed as MP1a (Figs 3c, d label single MP1a neurons) and MP1b (Fig. 3e labels a single MP1b neuron) hereafter. The MP1a and MP1b cells project to various regions of the brain including the optic lobes (specifically from MP1a), suboesophageal ganglion (SOG) and the lateral protocerebral complex where the male-specific P1 neurons integrate multiple sensory cues and initiate courtship18,19.

Fig. 3.

Single-neuron labeling and manipulation of Dsk MP neurons. a–f Stochastic labeling of single MP3 (a), two MP3 (b), single MP1a (c and d) and single MP1b (e) neurons. Two MP3, one MP1a and one MP1b neurons are registrated in a standard brain (f). Scale bars, 50 μm. g The frequency of hs-Flp/Y; UAS > stop > CsChrimson-mVenus/+; DskGAL4/+ males with CsChrimson-mVenus expressed in indicated neurons for courters (n = 30, white bars) or non-courters (n = 73, black bars). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and p = 0.48 (n.s.), chi-square test. n.s. not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Among the 103 males we assayed for courtship and later successfully imaged for CsChrimson-mVenus expression, 30 actively courted and 73 did not initiate courtship (for details, see methods). The frequency of CsChrimson-mVenus expression in MP1a and MP1b neurons, but not MP3, is significantly higher in non-courters than that in courters (76.7% of non-courters vs. 70% of courters label the MP3 cell [p > 0.05]; 87.7% of non-courters vs. 63.3% of courters label the MP1a cell [p < 0.01]; 79.5% of non-courters vs. 13.3% of courters label the MP1b cell [p < 0.001], Fig. 3b). Indeed, MP1a and MP1b neurons, but not MP3 neurons, project to the lateral protocerebral complex that is important for courtship initiation. Together these results illustrate the identity of individual MP cells, demonstrate their function in courtship inhibition, and suggest that the MP1a and MP1b cells may play more important roles then MP3 cells do in courtship inhibition.

Dsk and P1 neurons antagonistically regulate sexual arousal

It has been well established that the male-specific P1 neurons integrate chemosensory cues from potential mates and positively control male sexual arousal levels6,23–25,42. As Dsk neurons also project to the lateral protocerebral complex where inputs and outputs of P1 neurons both reside, we hypothesize that Dsk neurons may interact with P1 neurons to co-regulate sex and other arousal-related behaviors.

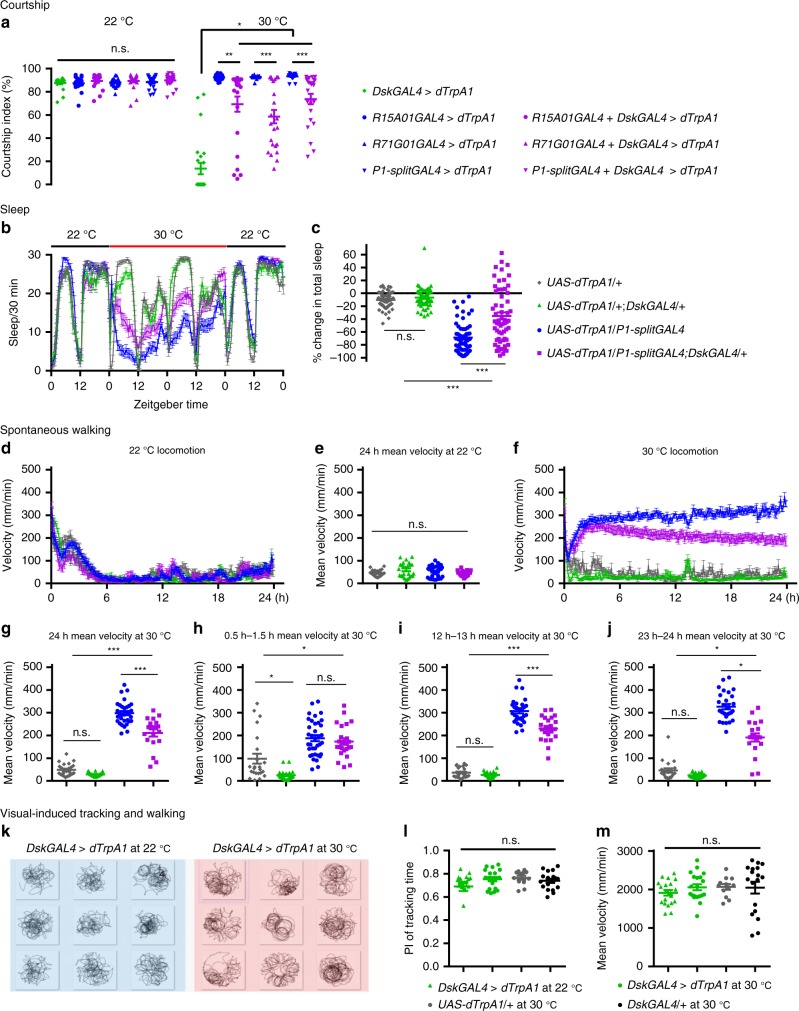

Firstly, we co-activated Dsk neurons and P1 neurons to test whether they function in a linear pathway where the downstream one may dominantly affect courtship. We used three independent P1 drivers (R15A01GAL4, R71G01GAL4, or P1-splitGAL4)23,33,42, and in all cases, we found that co-activation of Dsk and P1 neurons resulted in intermediate courtship levels compared to Dsk activation and P1 activation alone (Fig. 4a). These results indicate that Dsk and P1 neurons are not in a linear pathway, and they function antagonistically to modulate male courtship behavior.

Fig. 4.

Dsk and P1 neurons function antagonistically to regulate male sexual arousal. a Co-activation of Dsk and P1 neurons results in intermediate courtship levels. n = 24, 19, 17, 24, 24, 20, 24, 24, 20, 24, 24, 24, 24, and 24 respectively (from left to right). Genotypes as indicated. p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and p > 0.1 (n.s.) post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. b, c Dsk and P1 neurons oppositely regulate sleep. n = 60, 56, 57, and 60 respectively. p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.99 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. d, e Spontaneous walking velocity of individual males at permissive temperature (22 °C). n = 24, 24, 36, and 19, respectively. p = 0.07, One-way ANOVA. f–j Dsk and P1 neurons oppositely regulate spontaneous walking velocity. n = 24, 24, 32, and 19, respectively. For overall mean velocity (g): p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA. ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.1 (n.s.), post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For mean velocity from 0.5 h to 1.5 h (h): p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. *p < 0.05 and p > 0.99 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. For mean velocity from 12 h to 13 h (i): p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA. ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.1 (n.s.), post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For mean velocity from 23 h to 24 h (j): p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. *p < 0.05 and p > 0.99 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. k Representative walking trajectories in a visual-induced walking assay during a 6-min observational time. l, m Activation of Dsk neurons does not affect visual tracking ability or visual-induced walking speed. n = 20, 20, 12, and 18, respectively. For visual tracking performance: p = 0.3265, Kruskal–Wallis test; for walking speed: p = 0.3544, Kruskal–Wallis test. n.s. not significant. Error bars indicate SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Secondly, we tested how Dsk and P1 neurons may affect other arousal-related behaviors, e.g., sleep. We found that activation of P1 neurons dramatically decreased male sleep as previously reported33,44, but activation of Dsk neurons did not significantly affect sleep. However, we found that co-activation of Dsk and P1 neurons also resulted in intermediate sleep amounts (Fig. 4b, c), indicating that Dsk neurons indeed function antagonistically with P1 neurons on the control of sleep, in addition to the control of sexual behaviors.

To further confirm these findings, we used video tracking on individual males to measure spontaneous walking activity for 24 h, and observed similar results. Activation of P1 neurons alone promotes persistently high level of spontaneous walking for 24 h, while activation of Dsk neurons alone only mildly decreases spontaneous walking in the first hour, but does not significantly affect the average walking velocity for 24 h (Fig. 4f–j). Interestingly, we observed no difference between P1 activation and P1&Dsk co-activation males on their spontaneous walking activity during the first hour, but dramatic differences as activation proceeds, such that walking activity by P1&Dsk co-activation males is ~50% lower than P1 activated males, although still much higher than control males (Fig. 4f–j). These results clearly show that Dsk neurons function oppositely and persistently against P1 neurons on the control of spontaneous walking activity.

That activation of Dsk neurons mildly decreased spontaneous walking activity (at least initially) raises the possibility of a locomotion deficit. To rule out such possibility, we assayed their locomotion providing external stimuli. First, males with activated Dsk neurons walk and jump as quickly as control males when mechanically perturbed (Movie S2); second, males with activated Dsk neurons track rotating visual stimulus normally and walk as fast as control males in a visual-induced locomotion assay (Fig. 4k–m). That Dsk activated males rarely court females but normally track rotating visual stimulus further indicating that Dsk neurons negatively regulate an internal arousal state for sex and spontaneous walking, in opposite to the function of P1 neurons.

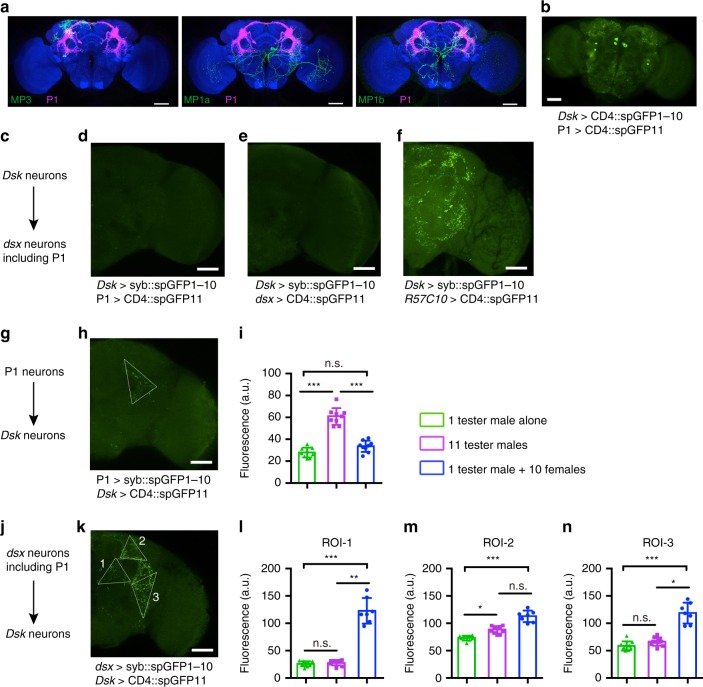

Dsk neurons receive synaptic transmission from P1 neurons

The above results demonstrate that Dsk and P1 neurons function oppositely to regulate internal arousal levels, but whether they interact with each other is unclear. We registrated individual MP3, MP1a, or MP1b neurons (Fig. 3a) with P1 neurons (labeled by P1-splitGAL4), and found that these MP neurons all have close contact with the P1 neurons (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Movie 3–5). Indeed, we observed substantial GRASP (GFP reconstitution across synaptic partners)45 signal between Dsk and P1 neurons (Fig. 5b), suggesting these neurons might have direct synaptic connection. We then used the recently modified activity-dependent GFP reconstitution method46. This method uses GFP1–10 fragment fused to the presynaptic synaptobrevin (syb::spGFP1–10) and a membrane tethered version of the complementing split GFP (CD4::spGFP11), and GFP reconstitution is achieved only if there are vesicle fusion between neurons labeled by corresponding GAL4 and LexA drivers. We first tested if Dsk neurons are presynaptic to P1 neurons by driving expression of syb::spGFP1–10 in DskGAL4 neurons and expression of CD4::spGFP11 in R15A01LexA labeled P1 neurons, and observed no GFP signal (Fig. 5c, d). As dsxLexA labels much more neurons involved in male courtship including P1 neurons, we repeated such activity-dependent GRASP experiment using DskGAL4 and dsxLexA, and did not observe any signal either (Fig. 5e). As a positive control to validate this technique, we observed substantial GRASP signal using pan-neuronal driver R57C10LexA (Fig. 5f). These results indicate that there is no direct synaptic connection from Dsk neurons to P1 neurons, but do not exclude the possibility that secreted DSK peptides might act on P1 neurons as long as there are DSK receptors expressed there. In fact, P1 neurons do express DSK receptor, and could be regulated by DSK, but see below for details.

Fig. 5.

Experience-dependent synaptic interaction between Dsk and P1 neurons. a Registration of P1 neurons and Dsk MP neurons in a standard brain. b Potential membrane contacts between P1 and Dsk neurons as revealed by conventional GRASP technique. Representative of five male brains. c–f There is no syb-GRASP signal from Dsk neurons to dsx neurons including P1 neurons. Representative of five male brains for each genotype. g–i Experience-dependent synaptic transmission from P1 neurons to Dsk neurons as revealed by syb-GRASP signals. n = 9 for each. p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA. ***p < 0.001, post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. j–n Experience-dependent synaptic transmission from dsx neurons (including P1 neurons) to Dsk neurons as revealed by syb-GRASP signals in single-housed males (green bar) and group housed males (magenta bar for male–male group, and blue bar for male–female group). n = 10, 10 and 7 for each group respectively. For ROI-1: p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.99 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. For ROI-2: p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 and p = 0.08 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. For ROI-3: p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 and p = 0.31 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. n.s. not significant. Error bars indicate SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

We then tested if P1 neurons might be presynaptic to Dsk neurons by driving expression of syb::spGFP1–10 in R15A01LexA labeled P1 neurons and expression of CD4::spGFP11 in DskGAL4 neurons, and observed reconstituted GFP signal specifically in the lateral protocerebral complex region (Fig. 5g, h), indicating that P1 neurons form direct synaptic connections with Dsk neurons. As such reconstituted GRASP signals are activity dependent, we compared these GRASP signals in males that have different housing experiences. We found that synaptic transmission from P1 to Dsk neurons, represented by the intensity of GRASP signal, are much stronger in male–male group-housed conditions (11 males), compared to single-housed and male–female group-housed (1 male + 10 females) (Fig. 5i). These results not only providing evidence of direct synaptic transmission from P1 neurons to Dsk neurons, but also indicating that such synaptic transmission is experience dependent and more efficiently induced by male–male group housing. We then tested the GRASP signal from all dsx neurons (including P1) to Dsk neurons (syb::spGFP1–10 driven by dsxLexA and CD4::spGFP11 driven by DskGAL4), and observed much more GRASP signals where they were divided into three parts as ROI-1, ROI-2, and ROI-3 for statistics (Fig. 5j, k). Comparing the intensity of GRASP signals under the above three housing conditions, we found, in all ROIs, GRASP signals were significantly enhanced by housing a male with ten females, where only in ROI-2 (overlaps with GRASP signals that from P1 to Dsk, see Fig. 5h) GRASP signals were significantly enhanced by male–male group housing, suggesting distinct properties of synaptic transmission from different dsx (e.g., P1 vs. pCd and pC2) neurons to Dsk neurons. We tried LexA drivers labeling pCd (R41A01-LexA) or pC2 (R40F04-LexA), as well as many other neurons (we do not have clean drivers for pCd and pC2 yet), but did not observe any GRASP signal from these LexA labeled neurons to Dsk neurons, probably due to the weak labeling of pCd and pC2 neurons by these LexA lines. Generating better genetic tools to label subsets of dsx neurons will help to understand how different populations of dsx neurons interact with Dsk neurons to regulate male courtship. Together these results indicate that Dsk neurons receive direct synaptic transmission, in an experience-dependent manner, from dsx neurons including P1 neurons.

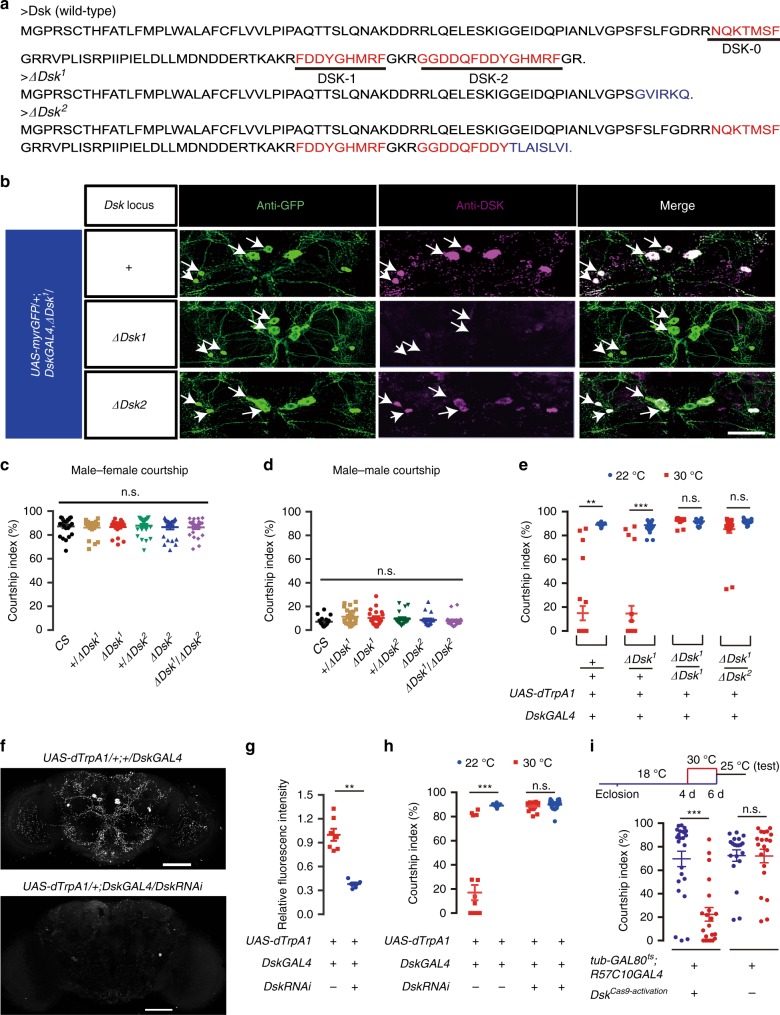

DSK peptides inhibits male courtship behavior

The above results establish that four pairs of Dsk- and fruM-expressing neurons function antagonistically with P1 neurons to regulate male courtship, but whether these Dsk neurons function through DSK peptides is unclear. The Dsk gene encodes three mature peptides DSK-0, DSK-1 and DSK-2 (Fig. 6a), two of which (DSK-1 and DSK-2) are Cholecystokinin (CCK)-like peptides39,47. We generated two deletion alleles of Dsk using the CRISPR/Cas9 technique48,49, which we termed ∆Dsk1 and ∆Dsk2 (Fig. 6a). ∆Dsk1 leads to deletion of all three peptides, and ∆Dsk2 only results in mutation of the DSK-2 peptide. Indeed, we observed no anti-DSK signal in homozygous ∆Dsk1 flies, and weaker signals in ∆Dsk1/∆Dsk2 flies, as the DSK antibody recognizes both DSK-1 and DSK-2 (Fig. 6b). These Dsk mutant males are fully viable and fertile, and court vigorously to females like control males (CIs > 80%, Fig. 6c). We also checked male–male courtship and did not observe obvious phenotype (Fig. 6d). These results indicate that loss of DSK in an otherwise wild-type fly does not obviously affect male courtship behaviors.

Fig. 6.

DSK peptides inhibit male courtship behavior. a Predicted amino acid sequence and mature peptides from the Dsk gene in wild-type, ∆Dsk1 and ΔDsk2 flies. b Validation of ∆Dsk mutants by anti-DSK staining. Representative of 5 male brains each. Arrows indicate cell bodies of MP neurons. Scale bars, 50 μm. c Dsk mutant males have normal courtship toward virgin females. Genotypes as indicated. n = 24 for each. p = 0.22, Kruskal–Wallis test. d Dsk mutant males do not show abnormal male–male courtship. n = 20 for each. p = 0.42, Kruskal–Wallis test. e Courtship inhibition by activating DskGAL4 neurons is dependent on the DSK-2 peptide. n = 24 for each. p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.1 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. f Down-regulation of Dsk gene expression using UAS-DskRNAi as revealed by anti-DSK staining in males raised at 22 °C. Scale bars, 50 μm. g Quantification of anti-DSK signal in the brain. n = 7 and 6. ***p < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U test. h Courtship inhibition by activating DskGAL4 neurons is dependent on DSK, as knocking down Dsk by RNAi restores courtship by DskGAL4/UAS-dTrpA1 males at 30 °C. n = 24 for each. p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test. ***p < 0.001 and p = 0.85 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. i Acutely over expression of DSK peptides two days before courtship test significantly suppresses male courtship. n = 24, 21, 20, and 20, respectively. p < 0.001, Kruskal–-Wallis test. ***p < 0.001 and p > 0.99 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. n.s. not significant. Error bars indicate SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To determine whether release of DSK peptides from Dsk neurons is responsible for courtship inhibition, we activated Dsk neurons in the above Dsk mutant background. We used homozygous ∆Dsk1 males as the null mutant for all three DSK peptides, and its combination with ∆Dsk2 as well as homozygous ∆Dsk2 as specific mutants for the DSK-2 peptide. We found that courtship inhibition by activation of Dsk neurons is fully dependent on secretion of DSK peptides, particularly the DSK-2 peptide, as loss of DSK-2 fully restores courtship of DskGAL4/UAS-dTrpA1 males at 30 °C (CI > 80%), comparable to wild-type courtship (Fig. 6e). These results indicate that DSK-2 is indispensable for courtship inhibition in males with Dsk neurons being activated, and further evidences are needed to reveal the role of DSK-1 in courtship inhibition. Furthermore, we knocked-down Dsk using RNA interference (RNAi)50,51, which significantly decreased DSK immunoreactivity (Fig. 6f, g), and found that courtship behavior was also restored in DskGAL4/UAS-dTrpA1 males at 30 °C (CI > 80%, Fig. 6h). We also found that activation of Dsk neurons in DskGAL4/UAS-TrpA1 males at 30 °C for 30 min decreased DSK immunoreactivity in many parts of Dsk neurons including soma, suggestive of DSK secretion in response to neuronal activation (Supplementary Fig. 6). Taken together these results demonstrated that DSK secretion from Dsk neurons is responsible for courtship inhibition in males with activated Dsk neurons.

As we did not observe increased courtship in Dsk mutant males, probably due to already high levels of male–female courtship or potential compensation to the loss of DSK modulation, we set out to test whether acutely increased expression of DSK in an otherwise wild-type fly would inhibit male courtship. We utilized a newly invented technique using Cas9 transcriptional activators to activate gene expression52,53, and found that acutely over expression of Dsk two days before courtship assay, using temperature dependent tub-GAL80ts, significantly decreased male courtship, compared to both genetic and temperature controls (Fig. 6i). Together these results indicate that DSK peptides released from Dsk neurons inhibit male courtship behavior.

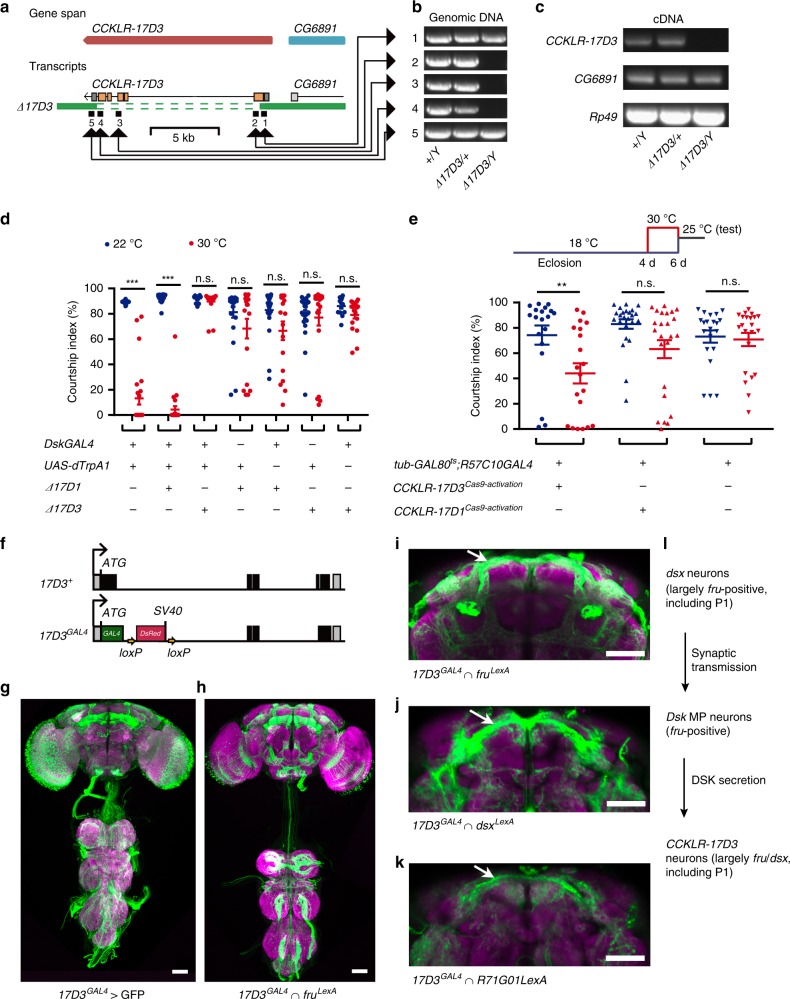

DSK inhibits male courtship through its receptor CCKLR-17D3

DSK peptides have two G-protein coupled receptors: the CCK-like receptor (CCKLR) at 17D1 and 17D354,55. We found that Loss of CCKLR-17D1 using a deletion mutant Df(1)Exel9051 (∆17D1) did not restore courtship levels when activating Dsk neurons (Fig. 7d). We then generated a deletion mutation of CCKLR-17D3 (∆17D3) by CRISPR/Cas9 tools48,49. This deletion removes the start codon and the coding sequence of CCKLR-17D3 (Fig. 7a–c). We found that the courtship-inhibiting effect of activating Dsk neurons was abolished in ∆17D3 males (Fig. 7d), indicating that DSK functions through its receptor CCKLR-17D3 but not CCKLR-17D1 to inhibit male courtship.

Fig. 7.

CCKLR-17D3 inhibits male courtship. a–c Generation and validation of a 9.04 kb deletion mutant of the CCKLR-17D3 gene. d Courtship inhibition by activating DskGAL4 neurons is dependent on DSK’s receptor CCKLR-17D3 but not CCKLR-17D1, as mutation in CCKLR-17D3 but not in CCKLR-17D1 restores courtship by DskGAL4/UAS-dTrpA1 males at 30 °C. Genotypes as indicated. n = 24, 24, 24, 24, 24, 24, 18, 24, 18, 24, 24, 24, 18, and 13, respectively. ***p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test. e Acutely over expression of CCKLR-17D3 but not CCKLR-17D1 two days before courtship test significantly suppresses male courtship. n = 19, 20, 24, 24, 21, and 22 respectively. p < 0.01, Kruskal–Wallis test. **p < 0.01 and p > 0.1 (n.s.), post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. n.s. not significant. Error bars indicate SEM. f Generation of knock-in GAL4 into the CCKLR-17D3 locus. g Expression pattern of 17D3GAL4 visualized by UAS-myrGFP in male CNS. Representative of eight males. h, i Intersectional expression between 17D3GAL4 and fruLexA in the male CNS. Representative of five males. Arrow indicates the male-specific P1 neurons (i). Genotype: 17D3GAL4/Y; UAS > stop > myrGFP LexAop2-FlpL/+; fruLexA/+. j, k Intersectional expression between 17D3GAL4 and dsxLexA (j), 17D3GAL4 and R71G01LexA (k) in males. Representative of five males each. Arrow indicates the male-specific P1 neurons. Scale bars, 50 μm. l An illustration from dsx neurons acting on Dsk neurons via synaptic transmission, and Dsk neurons to CCKLR-17D3 neurons via secretion of DSK. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To further confirm the role of CCKLR-17D3 on male courtship inhibition, we used the same technique52,53 as above activating Dsk expression to activate CCKLR-17D3 expression, and found that acutely over expression of CCKLR-17D3 two days before courtship assay significantly decreased male courtship behavior (Fig. 7e). In contrast, over expression of CCKLR-17D1 did not significantly affect male courtship (Fig. 7e). These results provide further evidence that DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling inhibits male courtship behavior.

DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling responds to past experiences

In order to further understand the physiological role that DSK signaling plays, we measured the level of DSK and CCKLR-17D3 expression using quantitative real-time PCR, and found that DSK/CCKLR signaling responds to multiple physiological conditions, including re-feeding, aging, group-housing and P1 neuronal activation (Supplementary Fig. 7). Since we also found that group-housing enhanced synaptic transmission from P1 neurons to Dsk neurons according to the activity-dependent GRASP signals (see Fig. 5i), we asked whether group-housing may affect male courtship in a DSK-dependent manner. We first tested male–female courtship by single-housed males or group-housed males (11 males, the same as used in Fig. 5i), and found no difference of male courtship in wild-type control males and Dsk knocked-down males (R57C10GAL4/UAS-DskRNAi) (Supplementary Fig. 8a). We then repeated male courtship, but tested in restricted conditions (headless females as targets under dark condition) to reduce redundancy of sensory stimulus on courtship56, and found that group-housing significantly reduced male courtship under these conditions; however, such group-housing induced courtship reduction is not observed in Dsk knocked-down males, as they courted equally high under two rearing conditions (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These results indicate that DSK signaling responds to multiple physiological states and past experiences, and at least male–male group-housing experience increases DSK expression and reduces male courtship.

CCKLR-17D3 in fruM neurons inhibits male courtship

We showed that DSK functions in four pairs of fruM-positive neurons to inhibit male courtship, and acts through its receptor CCKLR-17D3, but where CCKLR-17D3 functions to inhibit male courtship in unknown. As we failed to generate a functional CCKLR-17D3 antibody, we made a knock-in GAL4 into the CCKLR-17D3 locus (17D3GAL4) to recapitulate its expression (Fig. 7f). We found that 17D3GAL4 drives expression broadly in the brain and the ventral nerve cord (Fig. 7g). To test whether 17D3GAL4 drives expression in fruM neurons, we used an intersectional strategy to label overlapping neurons between 17D3GAL4 and fruLexA. Interestingly, the intersectional neurons include the male-specific P1 neurons that are crucial for courtship initiation, and the mushroom bodies that are important for sleep and locomotion, as well as many other neurons (Fig. 7h, i). That 17D3GAL4 drives expression in P1 neurons is further confirmed by two other intersectional labeling experiments (Fig. 7j, k). Thus we have found a neuropeptide signaling that functions in the sex circuitry: Dsk MP neurons receive direct synaptic inputs from many dsx neurons including P1 neurons, and then act on many fruM and/or dsx neurons (including P1) via secretion of DSK peptides to fulfill their function (Fig. 7l). To further test the role of CCKLR-17D3, we knocked down its expression using RNAi in all fruM-expressing (fruGAL4), all dsx-expressing (dsxGAL4), or a subset of P1 neurons (P1-splitGAL4, ~10 pairs of P1 neurons), but found no difference for male courtship (Supplementary Fig. 9a). We then activated CCKLR-17D3 expression using above mentioned tools53,57 specifically in fruGAL4, dsxGAL4, or P1-splitGAL4 labeled neurons, and found that over expression of CCKLR-17D3 in all fruM or dsx neurons, but not P1 neurons alone, significantly decreased male courtship (Supplementary Fig. 9b). These results indicate that CCKLR-17D3 functions in many fruM and/or dsx neurons (at least more than ~10 pairs of P1 neurons) to inhibit male courtship.

DSK signaling inhibits both male and female sexual behaviors

As we showed above that activating Dsk neurons also inhibited virgin female receptivity, we asked whether such inhibition in female sexual behavior depends on DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling. We found that suppression of female receptivity by activating DskGAL4 neurons also depends on DSK-2 and CCKLR-17D3 as loss of DSK-2 (UAS-dTrpA1/+; DskGAL4 ∆Dsk1/∆Dsk2, Supplementary Fig. 10a) or CCKLR-17D3 (∆17D3; UAS-dTrpA1/+; DskGAL4/+, Supplementary Fig. 10b) restores female receptivity to levels comparable to control females. Note that there is no P1 neuron in the female brain such that the P1-Dsk neuronal interaction is male-specific and does not account for female behaviors. As dsx neurons, particularly pC1 and pCd dsx neurons are important for virgin female receptivity58, we tested whether dsx neurons have direct synaptic transmission to Dsk neurons, as found in males (Fig. 5j–n). When syb::spGFP1–10 is driven by dsxLexA and CD4::spGFP11 driven by DskGAL4, we observed substantial GRASP signals in a ring-like shape in the lateral protocerebral complex that are important for sexual behaviors, and some other regions in female brains (Supplementary Fig. 10c). These results clearly show that Dsk neurons interact with sexually dimorphic dsx neurons in both sexes to suppress sexual behaviors.

Discussion

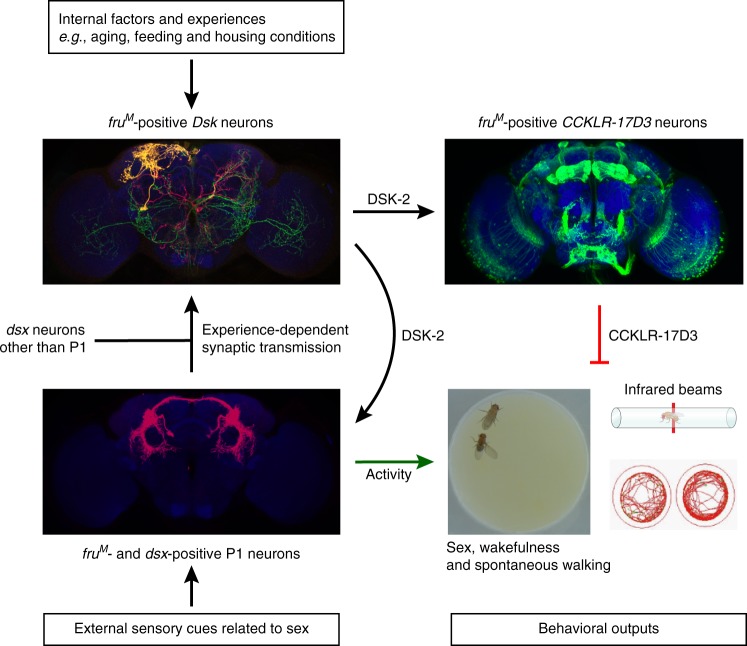

Our results identify, at single-neuron resolution, four pairs of fruM-expressing Dsk neurons (MP1 and MP3) that suppress male and female sexual behaviors. The suppression of male and female sexual behaviors depends on the secretion of the neuropeptide DSK-2, which then acts on one of its receptors CCKLR-17D3 that is expressed in many fruM neurons including P1 neurons and the mushroom bodies. Dsk neurons function antagonistically with courtship promoting P1 neurons to co-regulate male courtship, as well as sleep and spontaneous walking.

Cholecystokinin (CCK) signaling appears well conserved over evolution and modulate multiple behaviors47. In Drosophila, the CCK-like sulfakinin (DSK) is multifunctional and has been reported to be involved in regulating aspects of food ingestion and satiety40, aggression59, as well as escape-related locomotion and synaptic plasticity during neuromuscular junction development55. In mammals, CCK generated from the intestine acts on its receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the brain to transmit satiety signaling and thus inhibit feeding60. Furthermore, CCK signaling in the nucleus accumbens modulates dopaminergic influences on male sexual behaviors in rats61. CCK is also involved in nociception, learning and memory, aggression and depressive-like behaviors62–64.

Despite its significant and conserved roles in modulating multiple innate and learned behaviors, how CCK or DSK signaling responds to environment and/or internal changes, and acts on specific neurons expressing its receptors to modulate multiple behaviors, is still rarely known. Our finding that DSK/CCKLR signaling functions in the fruM- and/or dsx-expressing sex circuitry to inhibit male courtship is an effort to use Drosophila as a model to investigate how this conserved signaling modulates animal behaviors.

Our results uncovered a functional circuitry from many dsx neurons (including courtship-promoting P1 neurons) to four pairs of Dsk MP neurons via direct synaptic transmission, and these MP neurons then modulate CCKLR-17D3 neurons including many fruM and/or dsx neurons via secretion of DSK peptides. It is of particular interest to reveal how the four pairs of MP neurons integrate sensory information (in any), physiological states and past experiences in the future to better understand how this neuropeptide signaling modulate arousal states. We still do not know if these MP neurons receive sensory inputs, but since they receive inputs from many dsx neurons including P1 neurons that integrate multiple chemosensory information24,25, these sensory inputs will at least relay to Dsk MP neurons via P1. Whether there are other pathways from sensory inputs to MP neurons awaits further study. We also note that multiple physiological changes including feeding states, aging and sleep deprivation, as well as past housing conditions affect expression of DSK/CCKLR-17D3, but how they affect DSK signaling and behaviors is still unclear. We showed that male–male group-housing increases DSK expression and thereby reduces male courtship at least under a restricted condition, and previous findings also revealed opposite effects of group-housing on the excitability of P1 neurons in males that have fruM function or lack fruM function65,66. Such male–male housing experience may mildly reduce sexual arousal in a persistent manner, perhaps by increasing DSK expression, but how such housing condition affects physiological roles of Dsk MP neurons and P1 neurons awaits further functional imaging studies on a potential P1-Dsk-P1 functional loop (and a much complex dsx-Dsk-17D3 pathway) with sensory stimulation under different physiological states. In terms of the time scale that DSK functions to inhibit male courtship, our results indicate an immediate behavioral effect upon Dsk neuronal activation. We also note that activation of Dsk neurons inhibits male courtship and lasts for minutes, and previous findings also showed that activation of P1 neurons promoted wing extension and aggression and lasts for minutes42,65. These persistent behavioral effects may represent persistent arousal states regulated by Dsk and P1 neurons in this study; however, how this persistency is generated both in the circuit level and behavioral level still needs further investigation.

Dsk mutants do not have obvious courtship abnormality under our courtship assays. There are at least two possibilities: (1) DSK may function only in specific conditions (e.g., group-housing, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8) that increase its expression to inhibit courtship; and (2) There are redundant inhibitory signals for courtship, such as another neuropeptide SIFamide that acts on fruM neurons30,31, although they specifically inhibit male–male courtship. Further studies on how DSK/CCKLR signaling is activated under certain conditions, as well as how DSK, SIFamide and other inhibitory signals (if any) jointly modulate male courtship are needed to fully understand this. Nevertheless, that courtship inhibition by activation of Dsk neurons depends on DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling, and increasing such signaling through Cas9 activators in an otherwise wild-type male efficiently inhibited courtship, unambiguously reveal the role of DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling in suppressing sexual behaviors.

As DSK signaling modulates multiple behaviors, one may argue that its role in male courtship is not specific, e.g., activation of Dsk neurons may drive a competing behavior that phenotypically shunting male courtship. Although we cannot exclude such possibility, we listed a number of evidences as also summarized in Fig. 8 to support DSK’s role with specificity in courtship inhibition: (1) DSK functions in four pairs of fruM-expressing neurons to inhibit courtship; (2) males with activated Dsk neurons rarely court virgin females, while they follow rotating visual objects normally; (3) Dsk neurons receive synaptic transmission from courtship promoting P1 neurons (and many other dsx-expressing neurons) in an experience-dependent manner; (4) Dsk and P1 neurons antagonistically modulate sexual behaviors and wakefulness; and (5) DSK receptor CCKLR-17D3 inhibits male courtship and expresses in many fruM and/or dsx neurons including P1 neurons. We note that CCKLR-17D3 is expressed broadly in the CNS including not only P1 neurons, but also mushroom bodies that regulate a range of behaviors including learning, locomotion and sleep67. That DSK signaling is multifunctional is possibly due to broad expression of its receptors, and further studies on dissection of CCKLR function in subsets of neurons will help to understand how DSK/CCKLR signaling modulates multiple behaviors.

Fig. 8.

A model of DSK signaling regulating male sexual arousal. On one hand, male-specific P1 neurons that express both FRUM and DSXM integrate multiple sensory cues including both excitatory (e.g. from virgin females) and inhibitory (e.g. from males) information for courtship, and activation of P1 neurons persistently promotes male sexual behavior and wakefulness (reduction of sleep and increase of spontaneous walking), indicative of increased sexual arousal. On the other hand, four pairs of Dsk- and fruM-expressing neurons interact with P1 neurons to form a potential functional loop, and act through DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling in fruM circuitry to persistently inhibit male sexual behavior and wakefulness. The DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling responds to multiple physiological conditions including aging, feeding and group-housing experiences. Thus the interplay between internal states represented by DSK/CCKLR-17D3 signaling and external sensory stimulation represented by P1 neuronal activity orchestrates appropriate male sexual behavior

The decision for male flies to court or not depends on not only environmental cues such as availability and suitability of potential mates (males, virgin females, or mated females), but also their internal states (e.g., thirsty or sleepy). We propose that there are at least four factors affecting such a decision: (1) external cues that inhibit courtship, referred to as Ex-In factor, such as the male-specific pheromone cVA4; (2) external cues that are excitatory for courtship, referred to as Ex-Ex factor, such as courtship song68; (3) internal states that inhibit courtship, referred to as In-In factor; and (4) internal states that are excitatory for courtship, referred to as In-Ex factor. These factors dynamically change and jointly determine males’ decision to court or not.

Substantial progress has been made on how Ex-In and Ex-Ex factors jointly modulate the activity of male-specific P1 neurons, which is crucial for courtship initiation23–25. In contrast, much less is understood on In-In and In-Ex factors. Recently, Zhang and colleagues found that dopaminergic modulation of P1 neurons drives male courtship not only by desensitizing P1 to inhibition, but also by promoting recurrent P1 stimulation69,70, thus may act as an In-Ex factor for male courtship. Note that all the three factors mentioned above converge on P1 neurons, making them a decision-making center for male courtship. The DSK/CCKLR signaling we identified in this study is of particular interest, as it is likely to act as an In-In factor for male courtship, and above all, it does not simply act on P1 neurons like three other factors, but instead forms a potential functional loop with P1 neurons and antagonizes P1 function in modulating male courtship and wakefulness. That Dsk neurons receive synaptic transmission from P1 neurons and other dsx-expressing neurons in an experience-dependent manner further highlights a central role that the DSK/CCKLR signaling plays. These factors, excitatory vs. inhibitory, external vs. internal, jointly control appropriate performance of sexual behaviors, and further studies will reveal how P1 and other dsx-expressing neurons physiologically interact with Dsk neurons to balance behavioral output.

A prominent feature of the neuronal control of male and female sexual behaviors in Drosophila is that, despite large similarity in sensory systems, central integrative neurons are sex-specific in the two sexes, with dsx-expressing pC1 neurons integrating olfactory and auditory cues and promoting receptivity to courting males58, and fruM-expressing P1 neurons (largely overlapped with dsx-expressing pC1) integrating olfactory, gustatory, and auditory cues and promoting courtship to females24,25,68. In contrast, the four pairs of Dsk-expressing MP neurons we investigated in this study are sexually monomorphic and inhibit both male courtship and female receptivity. Thus DSK/CCKLR signaling may inhibit sexual behaviors in response to physiological changes that are common to both sexes, while sex-promoting central neurons integrating distinct sensory cues are sexually dimorphic. Interestingly, these Dsk neurons common to both sexes receive synaptic transmission from sexually dimorphic dsx neurons in both males and females, providing a simple solution to link sex-specific excitatory and sexually non-specific inhibitory control of sexual behaviors in males and females.

Methods

Fly stocks

Flies were maintained at 22 °C or 25 °C in a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. Canton-S flies were used as the wild-type strain. Neuropeptide-GAL4 lines38 used in Fig. 1b, UAS-dTrpA136, ∆17D1 [Df(1)Exel9051]55, UAS-CD4::spGFP1–10 LexAop-CD4::spGFP1145, UAS-CD4::spGFP11 LexAop-syb::spGFP1–10, and LexAop-CD4::spGFP11 UAS-syb::spGFP1–10 46 have been described previously and are from Bloomington Stock Center. Two SIFaGAL4 lines71 were kindly provided by Dr. Yi Rao. pBDPGAL4u, UAS-CsChrimson-mVenus41, UAS > stop > CsChrimson-mVenus68, UAS-mCD8RFP, UAS-myrGFP, UAS-Stinger-GFP, LexAop-RedStinger, LexAop2-myrGFP, LexAop2-FlpL, UAS > stop > myrGFP, fruGAL415 and fruLexA72 have been described previously73,74 and are obtained from Janelia Research Campus. UAS-DskRNAi was a gift from Tsinghua Fly Center (THU2073) at the Tsinghua University50,51. DskGAL4 (attP2), DskLexA (attP2), DskFlp (attP2), ∆Dsk1, ∆Dsk2, ∆17D3, 17D3GAL4, DskCas9−activation, CCKLR-17D3Cas9−activation, and CCKLR-17D1Cas9−activation are generated in this study and described below.

Genomic DNA and cDNA amplifications

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole fly body in extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0; 0.1 M EDTA; 1% SDS). Briefly, 30 flies were thoroughly crushed in extraction buffer with pestle. After incubation at 70 °C for 30 min, samples were lysed by adding potassium acetate to the final concentration of 800 mM, re-incubated on ice for 30 min. Precipitation was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. Half the volume of isopropanol was added to the supernatant, and precipitation was pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min. The pellet was washed with ice-cold 70% ethanol once, and the pellet was dried before resuspended in 100 μl of 100 mM Tris-HCl/100 mM EDTA plus with 5 μl RNase A (10 mg/ml stock).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Approximately 100 flies were transferred to a 15-ml tube chilled on liquid nitrogen, decapitated by vigorously vortexing the tube containing the flies. The fly heads were then separated from the bodies and other parts by using metal sieves (pore size #25 and #40). Total RNA was extracted from head of flies using a TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We used FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master /ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA USA) to conduct RT-PCR. RP49 was used as control for normalization. The primers used were as follows: RP49 (forward, 5′-CACACCAAATCTTACAAAATGTGTGA-3′; reverse: AATCCGGCCTTGCACATG), Dsk (forward, 5′-CCGATCCCAGCGCAGACGAC-3′; reverse: 5′-TGGCACTCTGCGACCGAAGC-3′) and CCKLR-17D3 (forward, 5′-ACGCGTACCCTGTACGTAGG-3′; reverse: GGTCTCGTTGTCAAGGTGGT). These primer sets were used for RT-PCR in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Generation of the DskGAL4 (attP2)

To make the DskGAL4 construct, a 1.1-kb sequence upstream of the Dsk gene was PCR amplified from wild-type Canton-S flies using primers 5′-ACGACGTCAAGCTTATGGTCGGTCTCACCGTCACACTGT-3’ and 5′-TAGGTACCATGCTTTACTGTGCCCTTGGCAGA-3′ (the added restriction sites were underlined), and was cloned into pBPGUw73 (a gift from Gerald Rubin, Addgene #17575) between the AatII and the KpnI sites.

Generation of the DskLexA (attP2)

To make the DskLexA construct, the same 1.1-kb sequence upstream of the Dsk gene (digested with HindIII/KpnI), together with the coding sequence of LexA::p65Uw (excised with KpnI and XbaI) from pBPLexA::p65Uw73 (a gift from Gerald Rubin, Addgene #26230) was cloned into pJFRC-MUH74 (a gift from Gerald Rubin, Addgene #26213) between the HindIII and the XbaI sites.

Generation of the DskFlp (attP2)

To make the DskFlp construct, the same 1.1-kb sequence upstream of Dsk gene (digested with HindIII/KpnI), together with the coding sequence of the Flp recombinase, was cloned into pJFRC-MUH74 (a gift from Gerald Rubin, Addgene #26213) between the AatII and the XbaI sites. All DNA constructs were verified by sequencing, and were integrated at the attP2 site on the third chromosome with PhiC31-mediated transgenesis.

Generation of the Dsk mutants

Two gRNAs (gRNA1: 5′-CATTCTCTCTATTCGGGGAC-3′; gRNA2: 5′-GACTACGGTCACATGCGTTT-3′) against Dsk were inserted into pCFD448 (a gift from Simon Bullock, Addgene #49411) as previously described. The Dsk-gRNA construct was then integrated at the attP40 site on the second chromosome. The Dsk-gRNA fly was crossed with vas-Cas9 to screen for Dsk mutation as previously described. Using this method, we obtained two Dsk mutants (ΔDsk1 and ΔDsk2, Fig. 6a). The following primers were used to confirm Dsk mutations:

forward: 5′-CAGTAAAGCATGGGACCTAGAAGCTGT-3′;

reverse: 5′-TGTGTGCTCGATTAATTTCTATGTACA-3′.

Generation of the CCKLR-17D3 mutants

Using the same method that generates the above Dsk mutants, we obtained the Δ17D3 mutant by using the following two gRNAs (gRNA1: 5′-GGTCATCCGGGATGTTCAAC-3′; gRNA2: 5′-TCAACAGTCCTCAGCTCTAA-3′) against CCKLR-17D3. Candidates of Δ17D3 were characterized by the loss of DNA band in the deleted areas by PCR on the genomic DNA, as shown in Fig. 7a. Primer sequences used for regions 1–5 in Fig. 7b are as follows:

Region 1: 5′-GCAAACACATAACGAGCCGAG-3′ and 5′-TATTGAAACGGCGACGCTTGC-3′

Region 2: 5′-GGGATGTTCAACTACGAGGAG-3′ and 5′-GCAGAGGAACTCGCCAAAGAT-3′

Region 3: 5′-CGCTACTACGCGATATGCCAT-3′’ and 5′-ATTATAGACTGCGGTGGCGGT-3′

Region 4: 5′-ACCACCTTGACAACGAGACCA-3′ and 5′-TTGGTGTTGGCACTCGCATAG-3′

Region 5: 5′-ATCAACGAGATGCGGTGTAAA-3′ and 5′-GCTTGTGCTCCACTCAACTGT-3′

Primer sequences used for amplifying CCKLR-17D3 or CG6891 cDNA in Fig. 7c are as follows:

CCKLR-17D3 cDNA: 5′-GGTCAAGATGCTGTTCGTCC-3′ and 5′-GGCGTTCATGAAGCAGTAGG-3′

CG6891 cDNA: 5′-TGGTGGAGAGCAAGCCGAGAA-3′ and 5′-GGATGCGTATGTAGCCAAAGG-3′

Generation of the 17D3GAL4 knock-in line

17D3GAL4 was generated by replacement of the first CCKLR-17D3 coding exon with GAL4::p65 (Fig. 7f). Firstly, two gRNAs (gRNA1: 5′-CCGCAACGGGACATGTCAGG-3′; gRNA2: 5′-CACGGCATGCCATTAGGGT-3′) against CCKLR-17D3 were inserted into pCFD4 as previously described48. Secondly, we fused GAL4::p65 into 5′ multiple cloning site of pHD-DsRed (a gift from Kate O’Connor-Giles, Addgene #51434) between the EcoRI and the NdeI sites. Then, each homologous arm was subcloned into the pHD-DsRed vector. The modified pCFD4 and pHD-DsRed plasmids were injected into the embryo of vas-Cas9 flies. The correct insertion was confirmed by 3xP3-DsRed screening and direct sequencing.

Generation of the Cas9 activating lines

In order to enhance expression of Dsk, CCKLR-17D3, and CCKLR-17D1, an effective and convenient targeting activator system, flySAM, was applied53. The primers for sgRNA were annealed and ligated with the flySAM digested with BbsI, and the resulting constructs were injected into y sc v nanos-integrase; attP40 embryos following standard injection procedures49,57. The following are the sgRNA primers for the transgenic activation lines used in this study:

Dsk forward: 5′-ttcgGCCCAGCGCCCTAATACAGA-3′

Dsk reverse: 5′-aaacTCTGTATTAGGGCGCTGGGC-3′

CCKLR-17D3 forward: 5′-ttcgCTCTGGCACTCAAGTGCCGT-3′

CCKLR-17D3 reverse: 5′-aaacACGGCACTTGAGTGCCAGAG-3′

CCKLR-17D1 forward: 5′-ttcgTTACCATCACTGAATCGTCG-3′

CCKLR-17D1 reverse: 5′-aaacCGACGATTCAGTGATGGTAA-3′

DSK antibody

Rabbit anti-DSK antibody was generated by using the peptide N′-FDDYGHMRFC-C′ that corresponds to the predicted DSK-1 and DSK-2 peptides as antigen, and used throughout except for Supplementary Fig. 1, in which the antibody was obtained from Dr. David Petzel and described previously75. The antiserum was purified and used at 1:100 dilution. The antigen peptide synthesis and antiserum production were performed by GenScript Corp. (Nanjing, China).

Male courtship assay

For courtship assay, 4–8 days old wild-type virgin females were loaded individually into round 2-layer chambers (diameter: 1 cm; height: 3 mm per layer) as courtship targets, and 4–6 days old tester males were then gently aspirated into the chambers and separated from target females by a plastic transparent film until courtship test for 10 min. Inter-male courtship is assayed the same as above but using two males of the same genotype. Courtship index (CI), which is the percentage of observation time a male fly performs courtship (e.g., chasing, wing extension, circling, copulation), was used to measure courtship, and scored manually using the LifeSongX software.

Ejaculation assay

For single fly ejaculation experiments, individual males were anesthetized with CO2 and then glued to a glass coverslip. After a 1-h recovery period in a humidified chamber, flies were recorded at 30 °C for 30 min and checked for ejaculation (Table S1).

Female receptivity assay

Four to eight days old virgin female flies and 4–6 days old wild-type virgin male flies were gently aspirated or iced singly into two layers of the round courtship chambers (diameter: 1 cm; height: 3 mm per layer) respectively and separated by a film between the layers. After about one hour’s acclimation, the film was removed to allow the paired flies to get in contact, and courtship was recorded by camera for 30 min. Receptivity was measured every two minutes as the cumulative percentage of females engaging in copulation.

dTrpA1 activation

Flies were maintained at 22 °C, cold anesthetized and loaded into behavioral chambers, and allowed to recover for at least 30 min at 22 °C. Chambers containing flies were then placed at the appropriate control (22 °C) or experimental temperatures (30 °C) for 30 min before behavioral tests.

CsChrimson activation

For all the CsChrimson experiments, crosses were set up on standard fly food in vials that covered by aluminum foil to protect from light. Tester flies were collected immediately after eclosion and reared in groups of 15–20 on 0.2 mM retinal (116–31–4, Sigma-Aldrich) food in vials that covered by aluminum foil for 4–6 days before courtship test. Courtship was performed as above described but either in dark (as control) or under red LED light stimulation (620 nm, 0.03 mW/mm2, Vanch Technology, Shanghai, China). Light intensity was measured by placing an optical power meter (PS-310 V2, Gentec, Canada) nearby the location of chambers. Fly behavior was recorded by a Stingray camera equipped with an infrared filter under 860-nm IR LED illumination (Vanch Technology, Shanghai, China).

Sleep test

Individual 2–4 day old males were placed in locomotor activity monitor tubes (DAM2, TriKinetics Inc) with fly food, and were entrained in 22 °C 12 h:12 h light: dark conditions for at least 2 days before sleep test. For sleep test in Fig. 4b, 1-day sleep data were recorded at 22 °C as baseline, then flies were shifted to 30 °C for two days, and returned to 22 °C for one day. Sleep was analyzed using custom designed Matlab software76. Change in total sleep (e.g. Figure 4c) is the percentage of sleep change in the first day of temperature shift (30 °C) compared to baseline sleep at 22 °C.

Spontaneous locomotion assay

Flies were transferred singly into round wells of 2-cm diameter and 3-mm height covered by regular food, and recorded for 24 h starting from 9 am under constant light condition. The average walking velocity during the 24-h recording was quantified using the ZebraLab software system (ViewPoint Life Sciences, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) as previously used33,44.

Visual-induced locomotion assay

We used a LED arena to evaluate optomotor response and visual-induced walking activity of flies. In brief, individual wing-cut male flies were allowed to walk for 6 min on a circular platform, 86 mm in diameter, surrounded by a water-filled moat to prevent escape. The moat was surrounded by a panoramic LED display, 290 mm in diameter and 345 mm in height. The LED display was a cylinder of evenly distributed 128 (row) × 32 (column) LED units and was computer-controlled with LED Studio software (Shenzhen Sinorad Medical Electronics, Shenzhen, China). The refresh rate of the LED panels was 400 Hz. A camera (WV-BP330, Panasonic System Networks, Suzhou, China) directly above the arena was connected to a computer to record the fly’s walking track at a rate of 12 frames per second, and position coordinates of the fly in each frame were calculated using Limelight software (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA, USA).

The flies was presented with VisionEgg77 generated horizontally moving gratings (spatial frequency:12/128; contrast: 100; temporal frequency: 3 Hz; orientation: 180°) first with 3 min clockwise rotation and then 3 min counter-clockwise rotation. Optomotor performance index was measure by the equation PI = (tsyn-tanti)/ (tsyn-tanti), in which tsyn means the time the fly’s turning was in the same direction as the grating movement while tanti means the time the fly’s turning was in the opposite direction as the grating movement. The average walking velocity during the 6-min test was also calculated to reflect visual-induced walking activity.

Feeding assay

Two feeding assays were used in this study. First, the capillary feeding assay (CAFE) was conducted as previously reported78 with slight modifications. Briefly, male flies were placed into 1.5-ml Eppendorf microcentrifuge tubes with 200 μl 1% agar for water consumption, each with an inserted calibrated pipets (5 μl, catalog no. 53432-706; VWR, West Chester, PA) with 2.5% sucrose, 2.5% yeast extract, and 0.1% propionic acid. Five food filled capillaries were inserted as controls in identical tubes without flies. The final consumption of food was determined as the decreased food level minus the average decrease in control capillaries. Daily consumption was measured over four consecutive days. Second, feeding was also assayed on food with blue dye. In brief, flies were starved for 24 h on 1% aqueous agarose at 22 °C. Then they were moved to 30 °C for 30 min for dTrpA1 activation. Thereafter, they were transferred to 1% FD&C Blue 1 (Sigma-Aldrich) colored food (2.5% sucrose, 2.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% agarose) for 15 min at 30 °C allowing feeding. The flies were observed under a light microscope and scored for blue color in their abdomens. To quantify the food intake of the flies more accurately, the absorbance of the ingested blue dye was measured as previously described79. 20 flies were decapitated, the bodies were collected in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes, homogenized in 500 μl distilled water, and centrifuged for 1 min at 12,000g. Three 100 μl samples of supernatant from each probe were taken, and absorbance of blue dye was quantified using a 96-well microplate spectrophotometer at 630 nm.

Tissue dissection, staining, and imaging

We dissected brains and ventral nerve cords of 4–6 days old male or female flies in Schneider’s insect medium (S2) and fixed them in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. After four washes of 15 min (4 × 15 min) in PAT (0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS), tissues are blocked in 3% normal goat serum (NGS) for 60 min, then incubated in primary antibodies diluted in 3% NGS for circa 24 h at 4 °C, then washed four times (4 × 15 min) in PAT and incubated in secondary antibodies diluted in 3% NGS for circa 24 h at 4 °C. Tissues are then washed four times (4 × 15 min) in PAT and mounted in Vectorshield (Vector Laboratories) for imaging. Primary antibodies used: rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen A11122, 1:1000), mouse anti-Bruchpilot (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank nc82, 1:30), rabbit anti-DSK (see antibody generation section, 1:100). Secondary antibodies used: goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:500) or Alexa 555 (1:500) and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:500) or Alexa 555 (1:500) (Molecular Probes). Samples were imaged at ×20 magnification on Zeiss 700 confocal microscopes, and processed with ImageJ.

To quantify DSK level in Dsk neurons, we co-stained the brains with DSK antibody and GFP antibody as control signals (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The samples of the same experiments were processed in parallel and using the same solution and imaged with the same laser power and scanning settings. With the imaged data, we got “Sum Slices” Z-projection of the substacks encompassing the cell bodies of eight MP1 and MP3 Dsk neurons and select the soma areas (or whole brain) to measure fluorescence intensity (FDSK and Fctrl), then select a small region without signal as the background fluorescence (BDSK and Bctrl) in both channels using ImageJ. Then we got the real signal in both channels by subtracting the background fluorescence from total signal respectively, and got the relative fluorescence of DSK as the ratio of DSK signal to the control signal ((FDSK - BDSK)/(Fctrl − Bctrl)).

Experience-dependent syb-GRASP quantification

For visualization of synaptic contacts, syb-GRASP method was utilized as previously described46. Briefly, Males were collected after eclosion under three housing conditions: singly housed, male–male group-housed (11 males) and male–female group-housed (1 male and 10 wild-type virgin females). Flies were transferred to vials with fresh food every three days, and males were dissected and imaged at the age of two weeks. Monoclonal mouse anti-GFP antibody (G6539, Sigma-Aldrich) was used to visualize reconstituted GFP.

All samples were stained and imaged under the same condition. Monochrome images were rendered to emphasize differences in intensity. For each region of interest (ROI), a maximum z-projection of a fixed number of image stacks with GRASP signals was created, and average fluorescence intensity was calculated for each sample.

Stochastic labeling and manipulation of Dsk neurons

Virgin hs-Flp;; DskGAL4 females were crossed with UAS > stop > CsChrimson-mVenus males at 25 °C on retinal food in vials that covered by aluminum foil. Heat shock was performed using 37 °C water bath for 10 min when early pupae begin to form. Males were collected after eclosion and fed in groups of 15–20 on retinal food in vials that covered by aluminum foil. Four to six days old males were assayed for courtship using wild-type females as targets under constant red light stimulation as above mentioned. One hundred and thirty two males were recorded for courtship for 30 min and analyzed into three categories: (1) 78 males did not initiate courtship (non-courters); (2) 19 males showed lower level of courtship and did not copulate with females; and (3) 35 males courted and successfully mated with females (courters). We then dissect the first (non-courters) and third (courters) categories after courtship assay and analysis, and image CsChrimson-mVenus expression using rabbit anti-GFP and secondary antibodies as above mentioned. 73 non-courters and 30 courters were successfully imaged and then analyzed for their expression in MP1a, MP1b, and MP3 neurons.

Brain image registration

The standard brain used in this study is described previously58. Confocal images for a single MP neuron (MP1a or MP1b, this study) and P1 neurons (P1-splitGAL4) were registered onto this standard brain with a Fiji graphical user interface (GUI) as described previously80.

Statistics

Experimental flies and genetic controls were tested at the same condition, and data are collected from at least two independent experiments. Statistical analysis is performed using GraphPad Prism and indicated inside each figure legend. Data presented in this study were first verified for normal distribution by D’Agostino–Pearson normality test. If normally distributed, Student’s t test is used for pairwise comparisons, and one-way ANOVA is used for comparisons among multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. If not normally distributed, Mann–Whitney U test is used for pairwise comparisons, and Kruskal–Wallis test is used for comparisons among multiple groups, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Tsinghua Fly Center, Janelia Research Campus and Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks. We thank Dr. Li Liu and Deliang Yuan for help with the visual tracking assay. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31622028, 31571093 to Y.P., 31772205 to S.W., and 6531000063 to C.G.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M581692 to S.W.), the Natural Science Foundation from Jiangsu Province (BK20160025 to Y.P.), the Jiangsu Innovation and Entrepreneurship Team Program, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2242018K41056 and 2242018K3DN07).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., C.G., S.D.L. and Y.P.; Methodology, J.C., C.H., H.Q. P.P. and Y.L.; Investigation, S.W., C.G., H.Z., M.S., Q.P., S.D.L. and Y.P.; Writing—Original Draft, Y.P.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.W., C.G., Q.P. and Y.P.; Funding Acquisition, S.W., C.G. and Y.P.; Supervision, Y.P.

Data availability

The source data underlying Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and Supplementary Figs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9, 10 are provided as a Source Data file. Sequences of ∆Dsk1, ∆Dsk2 and ∆17D3 that generated in this study were deposited to GeneBank (accession numbers are MN257953, MN257954 and MN257955 respectively). All relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Daisuke Yamamoto and other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Shunfan Wu, Chao Guo, Huan Zhao.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-12758-6.

References

- 1.Harbison ST, Mackay TF, Anholt RR. Understanding the neurogenetics of sleep: progress from Drosophila. Trends Genet.: TIG. 2009;25:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto D, Koganezawa M. Genes and circuits of courtship behaviour in Drosophila males. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:681–692. doi: 10.1038/nrn3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pool AH, Scott K. Feeding regulation in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014;29:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auer TO, Benton R. Sexual circuitry in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016;38:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoopfer ED. Neural control of aggression in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016;38:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson DJ. Circuit modules linking internal states and social behaviour in flies and mice. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016;17:692–704. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashikawa K, Hashikawa Y, Falkner A, Lin D. The neural circuits of mating and fighting in male mice. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016;38:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scammell TE, Arrigoni E, Lipton JO. Neural circuitry of wakefulness and sleep. Neuron. 2017;93:747–765. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sternson SM, Eiselt AK. Three pillars for the neural control of appetite. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017;79:401–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-104948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burtis KC, Baker BS. Drosophila doublesex gene controls somatic sexual differentiation by producing alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding related sex-specific polypeptides. Cell. 1989;56:997–1010. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryner LC, et al. Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell. 1996;87:1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito H, et al. Sexual orientation in Drosophila is altered by the satori mutation in the sex-determination gene fruitless that encodes a zinc finger protein with a BTB domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9687–9692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demir E, Dickson BJ. fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manoli DS, et al. Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature. 2005;436:395–400. doi: 10.1038/nature03859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockinger P, Kvitsiani D, Rotkopf S, Tirian L, Dickson BJ. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell. 2005;121:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villella A, Hall JC. Courtship anomalies caused by doublesex mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;143:331–344. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan Y, Baker BS. Genetic identification and separation of innate and experience-dependent courtship behaviors in Drosophila. Cell. 2014;156:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cachero S, Ostrovsky AD, Yu JY, Dickson BJ, Jefferis GS. Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Curr. Biol.: CB. 2010;20:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu JY, Kanai MI, Demir E, Jefferis GS, Dickson BJ. Cellular organization of the neural circuit that drives Drosophila courtship behavior. Curr. Biol.: CB. 2010;20:1602–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rideout EJ, Dornan AJ, Neville MC, Eadie S, Goodwin SF. Control of sexual differentiation and behavior by the doublesex gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:458–466. doi: 10.1038/nn.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinett CC, Vaughan AG, Knapp JM, Baker BS. Sex and the single cell: II. There is a time and place for sex. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura K, Hachiya T, Koganezawa M, Tazawa T, Yamamoto D. Fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron. 2008;59:759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]