Abstract

Infections with hepatitis C virus (HCV) are increasing among adolescents and adults born after 1965. Screening strategies may need to be adapted for this changing population. We surveyed trainees in different specialties about attitudes and practices related to HCV screening and identified specific barriers to screening across various healthcare settings. Constraints related to health system resources and the provider’s role were among the most common barriers cited across specialties, but pediatrics residents also cited barriers specific to their population, which can likely be addressed with targeted education.

Keywords: chronic hepatitis C, HCV screening, quality improvement, medical education

Introduction:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common blood-borne infection found in the United States population.1 The recent advent of direct-acting antivirals for HCV has revolutionized its management, prompting efforts to increase detection and making disease elimination possible. New cases of HCV are increasingly found among patients born after 1965—a shift driven by rising rates of injection drug use—yet current guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend HCV screening targeted only to the “birth cohort” of 1945–1965 or to those with documented risk factors.2 Screening strategies may need to be adapted as the epidemiology of HCV shifts toward populations with different healthcare utilization patterns. While there is not yet consensus about the need for expanded screening criteria, a number of centers in high prevalence areas are piloting protocols for universal screening, including our own large academic medical center.3,4

Targeted primary care-based screening alone may miss opportunities to detect and treat undiagnosed HCV among patients seeking care in diverse healthcare settings. For example, a recent study found an HCV seroprevalence of 3.9% among patients visiting a New York City emergency department (ED), and 19.2% of those cases were previously undiagnosed. Among undiagnosed HCV cases in that study, 39.5% of cases would be missed through birth cohort screening.3,4 Gaps in screening may also exist in primary care specialties that mainly care for patients outside the birth cohort. According to data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Kids’ Inpatient Database, there has been a 37% increase in HCV diagnoses among hospitalized children between 2006 and 2012.6 However, recent nationwide data from federally qualified health centers caring for adolescents found that only 36% of 13–21 year-olds diagnosed with opioid use disorders (OUDs) had been screened for HCV during routine visits.7 Even among primary care, addiction medicine and psychiatric providers treating OUD with opioid agonist therapy—the majority of whose patients are indicated for HCV screening under existing guidelines—perceived barriers to testing were common in a recent survey.8 Therefore, engaging providers from diverse specialties across the healthcare spectrum and identifying specialty-specific barriers to HCV screening will be critical to the successful implementation of treatment as prevention. As a first step to address this issue, we sought to understand the attitudes of trainees in the fields of Internal Medicine (IM), Emergency Medicine (EM), Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB/GYN) and pediatrics regarding HCV screening.

Methods:

We recruited participants from among trainees of residency programs in IM, EM, OB/GYN and pediatrics at a large academic medical center in New York City. All trainees of these programs were invited to complete an anonymous online survey designed to assess knowledge, attitudes and practices around sexual health with a focus on perceived barriers to HIV and HCV screening and referral for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. The invitation to participate was distributed via email by chief residents, program directors and faculty between August 2017 and August 2018. With respect to HCV, the survey consisted of questions assessing agreement with statements about HCV screening using 5-point Likert-type scales (1-strongly disagree; 5-strongly agree). Participants were also asked to rank up to three of 10 potential barriers to HCV screening. The potential barrier choices were divided into four different domains: barriers related to a) constraints on the health delivery system and competing demands on the provider’s role (n=3 barriers); b) follow up of results (n=3 barriers); c) specific aspects of a provider’s patient population (n=3 barriers); and d) financial reimbursement (n=1 barrier). For each domain, the inverse ranks of the component barriers were summed to produce a single value ranging from 0 to 6, such that for an individual respondent, a 0 value for a given domain indicated that none of a its component barriers were ranked, while a value of 6 indicated that all three of the individual’s ranked barriers were within that domain. This transformation was chosen to allow more meaningful statistical comparison across domains and specialties.

Kruskal-Wallace and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to assess the statistical significance of differences in responses to Likert-type questions and barrier ranking domains between specialties. This research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. All participants provided informed consent prior to completing the survey.

Results:

One hundred and forty-two trainees completed the survey with an overall response rate of 49%; n=66 IM residents, n=24 EM residents, n=14 OB/GYN residents and n=38 pediatric residents. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 37 (median = 29; IQR=3); 61.2% of participants were female; 64.8% identified as Caucasian/White, 19.7% Asian, 8.5% multiracial/other, 6.3% Hispanic/Latinx and 1.4% African-American/Black.

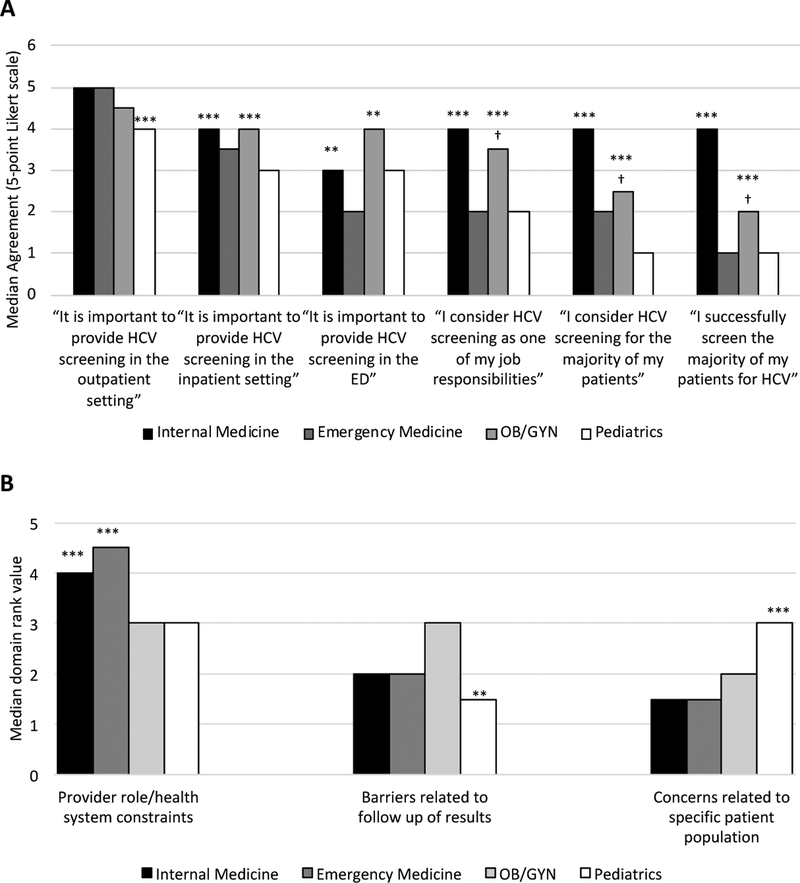

The majority of trainees in all specialties agreed with the importance of providing routine HCV screening in the outpatient setting, though pediatric residents had lower agreement than other specialties (p < 0.001; Figure 1A). Compared to EM and pediatrics residents, IM and OB/GYN residents had higher agreement with the importance of routine HCV screening in both the inpatient setting (p < 0.001) and in the emergency department (p < 0.01). EM residents were least likely to agree with the importance of screening in the ED setting. IM residents had higher agreement than other specialties with HCV screening being one of their job responsibilities (p < 0.001), and accordingly had higher agreement with considering screening (p < 0.001) and successfully performing HCV screening (p < 0.001) in the majority of their patients; OB/GYN residents also had higher levels of agreement with these items than EM and pediatric residents (p < 0.001), but lower than IM residents (p < 0.05).

Figure 1: Survey responses among resident trainees by medical specialty.

A. Screening settings and self-reported practices: median agreement by specialty on a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 indicating highest agreement. Except where otherwise indicated, p-value corresponds to comparison of specialties indicated with asterisk to all other specialties by Wilcoxan rank-sum.

B. Ranked barriers to screening by domain and specialty. Higher median ranking indicates higher importance. Reported medians include only responses in which at least one barrier within a domain was ranked by a participant. ED=Emergency Department.

*** p < 0.001

** P < 0.01

† p-value corresponds to comparison of OB/GYN residents with EM and pediatric residents.

The most common barriers to HCV screening cited by residents across all specialties related to the health delivery system and provider role constraints, including the need to attend to higher priority issues and limitations on time and resources, especially among IM and EM residents (p < 0.001; Figure 1B). Pediatric residents were significantly more likely than other specialties (p < 0.001) to cite barriers related to their specific patient population (minors), including issues surrounding the care of minors, a belief that HCV screening was outside their scope of practice and perceived low HCV prevalence among their patients. Conversely, pediatric residents were less likely to cite barriers related to result follow up than other specialties (p < 0.01). Only one respondent (from an EM training program) ranked financial reimbursement as a barrier to HCV screening.

Discussion:

Among resident trainees in four disciplines, there was substantial support for routine HCV screening in the outpatient setting. However, residents varied in their level of agreement with the importance of routine screening during inpatient encounters and ED visits. A substantial proportion of residents in EM, OB/GYN and pediatrics did not consider HCV screening to be one of their job responsibilities. Moreover, while the majority of IM residents did view HCV screening to be their responsibility; only half of IM residents reported successfully screening the majority of their patients for HCV.

The most commonly reported barriers to providing HCV screening across all specialties related to health system resource constraints and the demands placed on the provider, suggesting a role for engaging nursing and other support staff in expanding screening. This is consistent with previous research about the expansion of HIV testing, in which the availability of dedicated support staff was identified as a critical factor to facilitate screening in a busy emergency department setting.9 Successful implementation of universal HCV screening protocols has recently been reported in both ED3 and inpatient settings.4 These efforts included dedicated outreach workers to follow up results and link patients to HCV treatment; this will likely be an essential component of successful screening expansions in other high acuity settings. Interventions that incorporate information technology to streamline linkage to care may also play a role in expanding screening by automating procedures and minimizing the time required of healthcare providers.

Additional measures will be needed to address the specific concerns of providers who do not identify HCV screening as part of their responsibility. For example, pediatric residents—who routinely care for patients up to the age of 21—were most likely to cite low HCV prevalence as a barrier to screening. Recent data indicate that HCV prevalence is rising among pediatric patients in association with increased rates of substance use.6 However, HCV cases in adolescents are likely underreported due to low rates of screening,7 perpetuating a gap in knowledge about HCV’s shifting epidemiology. Pediatric residents also commonly listed issues surrounding minors as a potential barrier to HCV screening. Targeted education about community standards for confidentiality in minors and the changing epidemiology of both substance use and HCV among adolescents are needed to increase HCV screening among pediatricians. Similarly, among OB/GYN residents there was a (non-significant) trend toward higher ranking of barriers related to follow up, highlighting a role for programs to link HCV-positive women identified during gynecologic or prenatal visits to appropriate specialty care for treatment.

In the setting of a widespread epidemic of OUD and injection drug use, expansion of HCV screening and treatment is now a critical public health priority. Our study suggests that screening programs can better engage a wide array of healthcare providers—and improve detection among young HCV-infected patients—by targeting the specific concerns of different specialties.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [T32AI007531] to JZ and an investigator-initiated research grant from Gilead Sciences to CC and MES. The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References:

- 1.Oster AM, Sternberg M, Nebenzahl S, et al. Prevalence of HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and viral hepatitis by Urbanicity, among men who have sex with men, injection drug users, and heterosexuals in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(4):272–279. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygeine. Hepatitis B and C: Annual Report of Activites 2016. New York, NY; 2017. https://cdn.hepfree.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/hepatitis-b-and-c-annual-report-2016.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chastain C, Johnson J, Miller K, et al. Universal hepatitis C virus screening in a Tennessee tertiary care emergency department Presented at the: ID Week; October 5, 2018; San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winetsky D, Zucker J, Slowikowski J, Scherer M, Verna EC, Gordon P. Preliminary Screening Results Outside the 1945–1965 Birth Cohort: A Forgotten Population for Hepatitis C? Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019;6(5). doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torian LV, Felsen UR, Xia Q, et al. Undiagnosed HIV and HCV Infection in a New York City Emergency Department, 2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(5):652–658. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barritt AS, Lee B, Runge T, Schmidt M, Jhaveri R. Increasing Prevalence of Hepatitis C among Hospitalized Children Is Associated with an Increase in Substance Abuse. J Pediatr. 2018;192:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein RL, Wang J, Mayer K, et al. HCV Screening Practices Among Adolescents and Young Adult in a National Sample of Federally Qualified Health Centers in the U.S In: San Francisco; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litwin AH, Drolet M, Nwankwo C, et al. Perceived barriers related to testing, management and treatment of HCV infection among physicians prescribing opioid agonist therapy: The C-SCOPE Study. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. May 2019. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnall R, Clark S, Olender S, Sperling JD. Providers’ Perceptions of the Factors Influencing the Implementation of the New York State Mandatory HIV Testing Law in Two Urban Academic Emergency Departments. Gerson LW, ed. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013;20(3):279–286. doi: 10.1111/acem.12084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]