SUMMARY

The transcription factor NRF2 confers cellular protection by maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and proteostasis. Basal NRF2 levels are normally low due to KEAP1-mediated ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation. KEAP1, a substrate adaptor protein of a KEAP1-CUL3-RBX1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, contains a critical cysteine (C151) that is modified by electrophiles or oxidants, resulting in inactivation of the E3 ligase and inhibition of NRF2 degradation. Currently, nearly all NRF2 inducers are electrophilic molecules that possess unwanted off-target effects due to their reactive nature. Here, we report a group of NRF2 inducers, ent-kaurane diterpenoid geopyxins, with and without C151 reactive electrophilic moieties. Among 16 geopyxins, geopyxin F, a non-electrophilic NRF2 activator, showed enhanced cellular protection relative to an electrophilic NRF2 activator, geopyxin C. To our knowledge, this represents the first detailed structure activity relationship study of covalent versus non-covalent NRF2 activators, showing the promise of non-covalent NRF2 activators as potential therapeutic compounds.

Keywords: NRF2, chemoprevention, geopyxin, natural product, drug discovery

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Liu et al. report the discovery of geopyxins as chemopreventive agents. They show that geopyxin F, despite not having an electrophilic moiety commonly associated with NRF2 activation, could activate NRF2 in a KEAP1-dependent, but Cys151 independent manner and that this geopyxin conferred greater cellular protection than a covalent homolog.

INTRODUCTION

The nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NFE2)-related factor 2 (NRF2)-Kelch like ECH associated protein 1 (KEAP1)-antioxidant response element (ARE) axis is the primary defense mechanism of our body against oxidative and xenobiotic stress(de la Vega et al., 2016; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015, 2017; Villeneuve et al., 2010; Zhang, 2006). KEAP1 is an adapter protein for the Cullin3 (CUL3) E3 ligase complex that binds NRF2 in a 2:1 KEAP1:NRF2 ratio, with one KEAP1 binding an ETGE motif and the other binding a DLG motif on NRF2 and allowing for constant ubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation of NRF2(Cullinan et al., 2004; Kobayashi et al., 2004; Tong et al., 2006a; Tong et al., 2006b; Tong et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2004). This keeps the levels of NRF2 low under unstressed conditions. Upon exposure to oxidative or xenobiotic (usually electrophilic) insult, KEAP1 can be modified at one of its sensor cysteines, most commonly Cys151(Zhang and Hannink, 2003). This modification leads to a structural rearrangement that disrupts the interaction between one KEAP1 subunit and the DLG motif of NRF2, but preserves the other interaction between ETGE and NRF2, preventing further ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of NRF2(Baird et al., 2013; Tong et al., 2006b). This leads to an increase in the cytosolic levels of NRF2, which then translocates into the nucleus, dimerizes with a small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (sMAF) protein, and initiates the transcription of ARE-regulated genes(Itoh et al., 1997; Nioi et al., 2003). Most of the genes regulated by NRF2 are antioxidant and detoxification enzymes designed to counteract the effects of a given insult(Hayes and Dinkova-Kostova, 2014; Thimmulappa et al., 2002).

The protective NRF2 pathway has been shown to be activated in response to a number of natural compounds in foods and to provide protection against a number of environmental insults and pathogeneses (Chen and Kong, 2004; Jeong et al., 2006; Kwak and Kensler, 2010; Kwak et al., 2004; Rojo de la Vega et al., 2016; Yu and Kensler, 2005). For this reason, there are ongoing efforts to discover compounds, both natural and synthetic, capable of activating the NRF2 pathway that can be used as chemopreventive agents. The best studied of these compounds is the isothiocyanate, sulforaphane (SFN), found in cruciferous vegetables(Dinkova-Kostova et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 1994). SFN has been in clinical trials in China as a potential chemopreventive agent to protect people against liver cancer(Egner et al., 2011) and is currently in a number of clinical trials for a variety of indications (clinicaltrials.gov). In addition, the semi-synthetic triterpenoid, bardoxolone, has been in clinical trials for a variety of indications primarily related to kidney disease(Hong et al., 2012; Pergola et al., 2011a; Pergola et al., 2011b; Shepler et al., 2012; Thomas and Cooper, 2011; Zhang, 2013). However, to date, these compounds have failed to receive FDA approval, likely resulting from the promiscuous nature of the electrophilic pharmacophore that leads to toxicities. In efforts to thwart this toxicity, a number of groups have reported non-covalent, small synthetic compounds that block the protein-protein interaction between KEAP1 and NRF2, however, no such compound has entered the clinic at this point (Bertrand et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015; Zhuang et al., 2014). Herein, we report the discovery of the ent-kaurane diterpenoid, geopyxin A, as a classical, covalent NRF2 inducer. Further structure activity relationship studies revealed other members of this class were also NRF2 inducers, including geopyxins lacking a Michael acceptor. Interestingly, the non-covalent NRF2 activating compound, geopyxin F, was not as potent as the covalent activators in our cellular evaluations, but was less toxic and more effective at protecting cells from toxicants. These studies represent the first direct structure activity relationship studies comparing the biological effects of structurally similar compounds that interact with KEAP1 in a covalent or a non-covalent manner and offer important future considerations for the development of clinical NRF2 activators.

RESULTS

The geopyxins are effective NRF2 activators

In our continuing efforts to discover new activators of the NRF2 pathway with improved properties(de la Vega et al., 2016; Harder et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2015; Tao et al., 2015; Tao et al., 2013; Wondrak et al., 2008), we have evaluated a library of over 100 natural products isolated from Sonoran Desert plants, plant- and lichen-associated microorganisms, and some analogues derived from these natural products. Of these, geopyxins A–F (1–5), a group of ent-kaurane diterpenoids encountered in endolichenic fungal strains, Geopyxis aff. majalis and Geopyxis sp. AZ0066, and their analogues 6–16 were found to have interesting activity and were further investigated (Fig. 1) (Wijeratne et al., 2012). Among the active geopyxins were those with a Michael acceptor moiety that activate NRF2 in a KEAP1-Cys151 mediated manner, but geopyxin F (5) without this moiety also activated NRF2.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of geopyxins and their derivatives.

As a primary screen for activation of the NRF2 pathway, an MDA-MB-231 cell line stably expressing an ARE-luciferase reporter was used (Shen et al., 2015). In this assay, cells were treated with a given test compound for 16 hours and NRF2 levels were indirectly measured using luciferase with an ARE in its promoter as a reporter. This can be done in 96-well plates in a high-throughput manner. Using this assay, we screened a panel of natural products and some natural product derivatives in singlicate. As positive controls, two known NRF2 inducing compounds, sulforaphane (SFN) and tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ), were used. The vehicle (DMSO) was used as the negative control. A number of hits came from the initial screen that were validated in triplicate, but we were particularly interested in geopyxin A because of the unique architecture of this compound. In addition, we had a small panel of natural and semi-synthetic geopyxin analogs to conduct an SAR study. We therefore tested each of the geopyxins shown in Figure 1. The initial screening concentration for each of the geopyxins was established by measuring the LD50 of each compound in the ARE-luciferase cell line used for the screen. The LD50 values for each of the compounds are shown in Table 1. Each of the tested geopyxins and their derivatives (1–16) that showed a minimum of 1.5-fold induction of ARE-luciferase relative to the vehicle control, were then verified through a dose response. This provided an EC50 for induction of NRF2 (Table 1). Also shown in Table 1, are the maximum fold induction of NRF2 and a parameter, (LD50/EC50)*MI, where MI is the maximum induction, used to reflect the overall potencies of compounds.

Table 1.

NRF2 activationa and cellular toxicity of geopyxin analogs (1–16) and the positive controls, sulforaphane (SFN) and tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ).

| Geopyxin analog | LD50 [48 h] (µM) | EC50 (µM) | Max. induction (fold) | (LD50/EC50)*MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60.36 ±1.18 | 4.44±0.41 | 2.1 | 28.55 |

| 2 | 7.55 ± 0.67 | 0.87±0.18 | 1.5 | 13.02 |

| 3 | 51.29 ±1.23 | 2.33±0.35 | 2.1 | 46.23 |

| 4 | >128 | 36.36±2.20 | 4.1 | 14.43 |

| 5 | >128 | 71.52±5.80 | 3.0 | 5.37 |

| 6 | 8.69 ±0.93 | 2.32±0.17 | 2.2 | 8.24 |

| 7 | 10.68 ±1.55 | NIb | 1.2 | NAc |

| 8 | 9.02 ±0.78 | 0.92±0.26 | 1.9 | 18.63 |

| 9 | 19.99 ±2.08 | 5.08±0.57 | 1.8 | 7.08 |

| 10 | 21.54 ±1.56 | 1.22±0.15 | 1.6 | 28.25 |

| 11 | 44.03 ±3.29 | 2.22±0.24 | 1.6 | 31.73 |

| 12 | 6.7 ±0.47 | 1.24±0.04 | 1.8 | 9.73 |

| 13 | >128 | 73.13±0.87 | 1.9 | 3.33 |

| 14 | 123.63 ±3.89 | 54.54±5.10 | 4.2 | 9.52 |

| 15 | 115.11 ±3.57 | 26.81±4.08 | 3.5 | 15.03 |

| 16 | >128 | 70.38±5.12 | 1.6 | 2.91 |

| SFN | 46.2 | 0.97±0.18 | 1.9 | 90.49 |

| tBHQ | 85.1 | 2.43±0.34 | 2.2 | 77.05 |

Determined using ARE-luciferase NRF2 activation assay.

NI = Not investigated.

NA = Not active

Induction of autophagosome formation by geopyxin analogs.

Recent investigations of the NRF2 pathway have revealed a non-canonical (KEAP1-C151 independent) mechanism of activation through the autophagy pathway(Rada et al., 2011; Rojo de la Vega et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2014). One example of a non-canonical activator of NRF2 is arsenic. We have shown that treatment of cells with low levels of sodium arsenite blocks autophagosome maturation(Dodson et al., 2018a; Dodson et al., 2018b), which sequesters KEAP1 into autophagosomes in a p62 dependent manner(Jiang et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2010). This leads to increased NRF2 levels but fails to be protective due to blockage of autophagy, an essential process to remove misfolded proteins and damaged organelles to maintain proteostasis. Because this non-canonical activation of NRF2 is deleterious to cells, the effects of the geopyxins and their derivatives on autophagy were investigated. The standard assay to probe increase in autophagosome number is to use immortalized baby mouse kidney epithelial (iBMK) cells stably transfected with a GFP-LC3 fusion protein. If autophagosome number increases, this will be seen as increased fluorescent puncta (compare non-treated (NT) to arsenic treated iBMK cells in Fig. 2). As a negative control (NT, Fig. 2) the DMSO vehicle was used and as a positive control 1 µM NaAsO2 was used (As, Fig. 2). Figure 2 shows data only for compounds 3, 5 and 14. Each row shows three fields of view that were randomly selected. As can be seen, geopyxins C (3) and F (5) do not increase the number of autophagosomes relative to NaAsO2 or compound 14.

Figure 2.

Induction of autophagosome formation by geopyxin analogs. Immortalized Baby Mouse Kidney Epithelial Cells (iBMK) stably expressing GFP-LC3 were treated as indicated. Autophagosome formation was visualized by the formation of fluorescent puncta using fluorescence microscopy. NT: no treatment, As: 1 µM NaAsO2, 3: compound 3 (2.33 µM), 5: compound 5 (71.5 µM), and 14: compound 14 (54.5 µM). Each row shows three fields of view that were randomly selected.

NRF2 and its downstream genes are activated by compounds 3 and 5.

Based on the results obtained, toxicity versus NRF2 activation (Table 1, LD50/EC50*MI), and authophagosome formation (Fig. 2), geopyxins C (3) and F (5) were chosen for further investigation. Geopyxin C (3) is a classical NRF2 inducer, harboring a Michael acceptor moiety similar to 1–2, 4, and 6–12 (Fig. 1 and see below) that is poised to potentially react with Cys151 of KEAP1. In addition, compound 15 has an electrophilic epoxide that could react with Cys151. Because geopyxin C (3) had the highest (LD50/EC50)*MI (46.23) it was selected for further studies. Compounds 5, 13–14, and 16 all lack this D-ring Michael acceptor moiety, arguing for potential activation of the NRF2 pathway through a non-covalent mechanism. Moreover, geopyxin F (5) showed no cellular toxicity, arguing for a potentially larger therapeutic window, so 5 was selected as well. Although compound 14 is also likely a non-covalent NRF2 activator, its effects on autophagy (Fig. 2) eliminated it from further consideration.

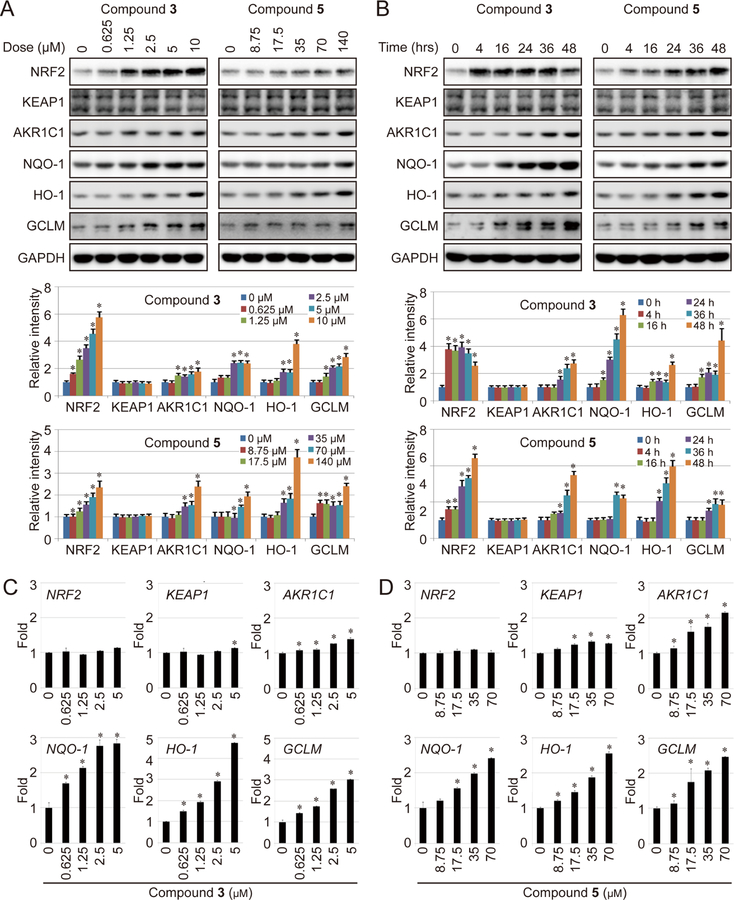

First, MDA-MB-231 cells were used for immunoblot analysis to study the effects of 3 and 5 on NRF2 and NRF2 downstream genes. Both compounds showed dose dependent increases in the level of NRF2 and the downstream target genes AKR1C1, NQO-1, HO-1, and GCLM (Fig. 3A). As expected from initial screening data, compound 5 required a higher concentration to achieve NRF2 activation (Fig. 2A). Based on these doses, cells were treated with 2.33 µM 3 or 71.5 µM 5 and the kinetics of activation were determined. As shown in Figure 3B, for compound 3 the levels of NRF2 increase rapidly, peaking at 4 hours, are steady over 24 hours, and then begin to decline after 48 hours. Whereas, the downstream genes rise more slowly and continue to be activated up to 48 hours. However, for compound 5 the level of NRF2 continues to steadily rise all the way up to 48 hours, ultimately achieving higher fold induction than the compound 3 treated cells. This slower kinetics of induction also explains the apparent lower-fold induction of NRF2 in the dose escalation studies (Fig. 3A). Downstream genes also show a slightly different pattern of induction with AKR1C1 and HO-1 showing greater fold induction and NQO-1 and GCLM showing lower fold induction. In addition, slightly different kinetics were observed with compound 3 peaking at an earlier timepoint. Neither compound 3 or 5 showed an increase in the levels for KEAP1, as expected. Next, the dose dependence of mRNA transcription was determined for compounds 3 (Fig. 3C) and 5 (Fig. 3D) using real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). As apparent from these data, in both cases the levels of NRF2 remained unchanged, but there was a slight, but statistically significant increase in the levels of KEAP1, but no corresponding increase in KEAP1 protein (Fig. 3A–B). The results for NRF2 are expected as it is regulated post translationally. In contrast, the mRNA levels of the downstream genes increased in a dose dependent manner, consistent with the immunoblot data.

Figure 3.

NRF2 and its downstream genes are activated by compounds 3 and 5. (A-B) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the indicated dose of 3 (left panel) or 5 (right panel) for 16 hours (A) or with 3 (2.33 µM) or 5 (71.5 µM) for the indicated time (B). The protein level of NRF2 and the indicated downstream genes was measured by immunoblot analysis. (C-D) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the indicated dose of compound 3 (C) or compound 5 (D) for 16 hours, mRNA expression of NRF2 and its downstream genes was measured by real-time qRT-PCR. AKR1C1 (Aldo-Keto Reductase 1 Member C1), NQO1 (NAD(P)H Dehydrogenase Quinone 1), HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1), and GCLM (Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase Modifier Subunit) are well-defined NRF2 target genes. All experiments were repeated in triplicate. Bar graphs represent the mean of three independent experiments and error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean. *: p<0.05 compared with the control group. Details of statistical analysis can be found in the STAR Methods.

Compounds 3 and 5 both block ubiquitylation and stabilize NRF2 in a KEAP1-dependent manner, but only 3 depends on Cys151 in KEAP1.

Next, the mechanism of NRF2 activation exhibited by 3 and 5 was explored further including KEAP1-Cys151 and ubiquitin dependence. To determine if NRF2 activation was KEAP1 dependent, we made an isogenic pair of wild-type (WT) and KEAP1−/− MDA-MB-231 cells, in which endogenous KEAP1 was knocked out using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, as we reported previously (Tao et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 4A, both compounds 3 and 5 failed to further activate the level of NRF2 in the KEAP1−/− cells, whereas there is a dose-dependent activation in WT cells. Next the ubiquitylation state of NRF2 was assessed using immunoprecipitation of NRF2 and blotting for hemagglutinin (HA) tagged ubiquitin. As shown in Figure 4B, NRF2 is robustly ubiquitylated in the absence of compound 3 or 5, but largely fails to be ubiquitylated in the presence of compound 3 or 5 or the positive control, SFN. Because both compounds blocked ubiquitylation, it was anticipated the half-life of NRF2 should be extended in the presence of compounds. To determine this, cells were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis, and NRF2 levels were measured at several time points. The level of NRF2 was plotted as a function of time by quantifying the immunoblots (Fig. 4C). As expected, both compounds increased the half-life of NRF2. Interestingly, compound 5 increased the half-life of NRF2 more than 3 times relative to untreated cells and more than 2 times relative to compound 3. Finally, to determine, if the compounds stabilize NRF2 in a KEAP1-Cys151 dependent manner, an exogenous copy of either KEAP1-WT or KEAP1-C151S was expressed in KEAP1−/− MDA-MB-231 cells followed by a dual luciferase assay using an ARE-promoted firefly luciferase and a TK-promoted Renilla luciferase and immunoblot to detect the level of NRF2. The dual luciferase assay showed that firefly luciferase could be induced by both compounds 3 and 5 in the presence of KEAP1-WT at a level comparable to SFN. However, in the presence of KEAP1-C151S, induction was only overserved with compound 5 and NaAsO2 (As), a positive control for a Keap1-C151 independent NRF2 induction (Fig 4D). As shown in Figure 4E (left panel, immunoblot; right panel, quantification of the blot), 3 increases the level of NRF2 in the presence of KEAP1-WT but not in the presence of KEAP1-C151S in a manner similar to SF, whereas, compound 5 increases the level of NRF2 equally in the presence of either KEAP1-WT or KEAP1-C151S, confirming the dual luciferase data. Overall, these data show that activation of NRF2 by 3 is Cys151 dependent, whereas activation by 5 is independent of KEAP1-Cys151.

Figure 4.

Compounds 3 and 5 both block ubiquitylation and stabilize NRF2 in a KEAP1-dependent manner, but only 3 depends on Cys151 in KEAP1. (A) KEAP1-WT and KEAP1−/− MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with compounds 3 (left panel) or 5 (right panel) for four hours. The protein level of NRF2 was measured by immunoblot (upper panels), the level measured by densitometry, and plotted relative to the GAPDH loading control (lower panels). (B) MDA-MB-231 cells, transfected by expression vectors for NRF2 and HA-Ubiquitin, were treated with one dose of compound 3 (2.33 µM) or 5 (71.5 µM) for 4 hours. Ubiquitylation of NRF2 was measured by immunoprecipitation of NRF2, followed by immunoblot analysis with an anti-HA antibody. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells were left untreated, treated with compound 3 (2.33 µM), or compound 5 (71.5 µM) for the indicated times. The protein level of NRF2 was measured by immunoblot analysis, the intensity of the NRF2 band (normalized to GAPDH) vs time was plotted and the half-life of NRF2 was calculated. (D-E) To determine the KEAP1-Cys151 dependence, MDA-MB-231-KEAP1−/− cells, established using the CRISPR-Cas9 technique, were transfected with either an expression vector for KEAP1 WT or KEAP1 C151 together with an NQO1-ARE-firefly luciferase and TK-Renilla luciferase vector. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with the indicated compound for 16 hours. Both firefly luciferase activity relative to Renilla luciferase activity (D) and the protein levels of NRF2 and KEAP1 (E) were measured (left panel) and the intensity of NRF2 bands (normalized to GAPDH) was plotted (right panel). Experiments were repeated in triplicate. Bar graphs represent the mean of three independent experiments and error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean. *: p<0.05 compared with the control group. Details of statistical analysis can be found in the STAR Methods.

Compounds 3 and 5 confer protection against xenobiotic insult in an NRF2 dependent manner.

Finally, the protective properties of 3 and 5 were determined by investigating cell viability in the presence of different concentrations of NaAsO2 or the chemotherapeutic agent, cisplatin. Both WT and KEAP1−/− MDA-MB-231 cells were used for these studies. First, WT cells and KEAP1−/− cells were treated with compounds 3, 5, SFN (positive control), or DMSO vehicle (negative control) and then challenged with dose escalating amounts of NaAsO2 or cisplatin and cell viability was measured using an MTT assay (Fig. 5A–B). Because protection (i.e. enhanced cell survival) was only observed in the WT cells, it was concluded that protection was conferred through the NRF2 pathway. In both cases, the greatest level of protection was seen with compound 5. Compound 3 had protection similar to SFN, perhaps a reflection of the similar Cys151 mediated NRF2 activation. As expected, there was no protection with any compounds in KEAP1−/− cells (Fig. 5A–B). Next, WT and KEAP1−/− cells were treated with the indicated compounds at 6 different concentrations (0 × EC50, ¼ × EC50, ½ × EC50, EC50, 2 × EC50, and 4 × EC50) and then challenged with NaAsO2 (20 µM) or cisplatin (10 µM). The results indicated a concentration-dependent protective effect of both compounds 3 and 5 (Fig. 5C–5D). Furthermore, the increased protection of compound 5 relative to compound 3 can be observed form a much steeper curve for compound 5 compared to compound 3 (compare Fig. 5D to Fig. 5C). Compound 5 had much faster kinetics and showed greater protection at each dose. In the present experiments, we used a KEAP1−/− cell line because we were unable to generate an NRF2−/− cell line in the MDA-MB-231 background. We did however explore this effect using mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells lacking Nrf2 and observed similar results (Fig. S1 in Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

Compounds 3 and 5 confer protection against xenobiotic insult in an NRF2 dependent manner. (A-B) WT MDA-MB-231 cells and KEAP1−/− MDA-MB-231 cells, were pre-treated with sulforaphane (2 µM), 3 (2.33 µM), or 5 (71.5 µM) for 4 hours to induce NRF2, then the indicated dose of arsenic (A) or cisplatin (B) was added for an additional 48 hours, in the presence of half the original concentration of sulforaphane (0.5 µM), 3 (1.16 µM), or 5 (35.8 µM). Cellular toxicity was measured by MTT assay. (C-D) WT or KEAP1−/− MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with compound 3 (C) or 5 (D) at different concentrations (0 x EC50, ¼ × EC50, ½ × EC50, EC50, 2 × EC50, and 4 × EC50) for 4 hours, then arsenic (20 µM) or cisplatin (10 µM) was added for an additional 48 hours. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate, points indicate the average of three experiments, and error bars are the standard deviations from the means. * indicates p < 0.05. Details of statistical analysis can be found in the STAR Methods.

DISCUSSION

To date, there is one compound in the clinic, dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®), used to treat relapsing multiple sclerosis, which is thought to activate the NRF2 pathway as its primary mode of action(Gao et al., 2014; Hammer et al., 2018). However, other compounds, SFN and bardoxolone, entered clinical trials, but were not approved due to toxicities(Dinkova-Kostova et al., 2017; Egner et al., 2011; Pergola et al., 2011a; Zhang, 2013). However, there are other ongoing clinical trials with bardoxolone and its derivatives for multiple indications (clinicaltrials.gov). Because of the toxicities associated with reactive electrophilic compounds, a number of groups have initiated programs to discover non-covalent NRF2 inducers(Bertrand et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015; Zhuang et al., 2014). These compounds are protein-protein interaction inhibitors that target the interaction between the Kelch domain of KEAP1 and the ETGE and DLG motifs of NRF2. In some of these studies, extensive SAR evaluations were carried out to optimize the pharmacodynamics of the compounds, but no comparison was made between structurally analogous electrophile containing compounds and non-electrophile containing compounds, comparisons were only made to non-isosteric electrophiles (i.e. SFN). An elegant study was carried out looking at reversible covalent bardoxolone derivatives versus non-reversible derivatives (Wong et al., 2016), but the aim of this study was to evaluate if bardoxolone engaged KEAP1 cysteines and if so, which cysteines, but not to compare covalent versus non-covalent activation of the NRF2 pathway. Here, because we are studying isosteric electrophilic and non-electrophilic compounds, we are able to gain valuable SAR insight.

We have discovered and explored a series of geopyxins that are NRF2 activators (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Using a collection of natural and semi-synthetic geopyxins, we have carried out an SAR analysis. We found that the presence of a D-ring Michael acceptor moiety led to the highest degree of activation, but that modifications to the A ring decreased this activity, especially the presence of polar substituents (compare 2 to 1, 3, and 9). Esterifying the A-ring carboxylic acid moiety or acetylation of the A-ring hydroxyl group also increased efficacy (compare 1 to 6 and 10). In each case, however, these changes also increased toxicity, likely all of these effects are due to increased cellular penetrance. It was however noted, that addition of a hydroxyl group to the C-ring dramatically increased activity and toxicity. The observed toxicity is due to an off-target effect, likely due to the reactive electrophile, as activation of the NRF2 pathway in itself is not toxic. In addition to those containing a Michael acceptor (or epoxide, 15) moiety, we explored four geopyxin analogs (5, 13-14, and 16) without a Michael acceptor moiety. Each of these compounds showed activation of the NRF2 pathway, likely indicating the ent-kaurane scaffold can form a specific binding interaction with KEAP1. Of these non-covalent activators, we chose geopyxin F (5) for more detailed analysis, as it showed good activation with no observed cellular toxicity and did not activate the autophagy pathway (see Fig. 2). Although geopyxin F (5) was not as potent as geopyxin C (3), it activated NRF2 in a KEAP1-Cys151 independent manner (Fig 4 D–E). This observation is important, as it demonstrates 5 does not eliminate the 17-OH group to regenerate the Michael acceptor, but most likely works through a non-covalent mechanism. Importantly, we also found that 5 was more protective in cells challenged with NaAsO2 or cisplatin. The precise reason for this heightened cellular protection remains to be resolved, but it seems this might be related to the kinetics of NRF2 activation (Fig. 3 A–B). As NRF2 levels rise, the level of glutathione (GSH) will also rise and GSH will readily react with a Michael acceptor, thus explaining the more rapid decrease in NRF2 levels when cells are treated with 3 (Fig. 3A) versus 5 (Fig. 3B). In any case, the enhanced protection observed certainly argues for this as a strategy to develop future NRF2 activating therapies. In the future, we aim to further optimize the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of these compounds and carry out protection studies in animal models.

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Eli Chapman (chapman@pharmacy.arizona.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

iBMK-EGFP-LC3 was kindly provided by Professor Eileen White. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. MDA-MB-231 cell was purchased from ATCC and cultured in MEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Where applicable, information concerning replication of experiments, the sample size analyzed, and the statistical method used for comparisons is provided in the figure legends.

METHOD DETAILS

Compound Collection

General methods and procedures used for isolation and preparation of compounds 1–12 described herein have already been published by our group (Wijeratne et al., 2012).

Preparation and Chemical Characterization of Compounds 13–16.

General Procedure for Preparation of 15α-Hydroxygeopyxins

To stirred solutions of geopyxins (6 or 12, 5.0 mg each) in MeOH (0.5 mL) at 0 °C were added CeCl3.7H2O (6.0 mg each) and continued to stir at 0 °C. To this solution was added NaBH4 (0.2 mg each) and stirred at 0 °C. After 10 min ice cold H2O (2.0 mL) was added to the reaction mixtures, MeOH was evaporated under reduced pressure and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5.0 mL). Combined EtOAc layers were washed with H2O, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to give crude products. These were separated by Prep. TLC to give (13, 5.0 mg, 99% and 14, 5.0, 99% respectively).

15α-Hydroxy-15-deoxy-methylgeopyxin A (13):

white amorphous solid; 1H NMR (acetone-d6, 400 MHz) δ 4.99 (1H, m, H-17a), 4.84 (1H, m, H-17b), 4.13 (1H, m, H-15), 4.01 (1H, br s, D2O exchangeable, OH-7), 3.69 (1H, br s, D2O exchangeable, OH-15), 3.62 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.48 (1H, m, H-7α), 3.42 (1H, dd, J = 3.5, 1.6 Hz, H-1β), 2.95 (1H, m, H-11a), 2.57 (1H, t, J = 4.4 Hz, H-13), 2.10 (1H, dt, J = 13.6, 4.0 Hz, H-3a), 2.09 (1H, m, H-5), 2.05 (1H, m, H-6a), 1.97 (1H, m, H-2a), 1.91 (1H, m, H-6b), 1.82–1.76 (2H, m, H-9 and H-14a), 1.68–1.64 (2H, m, H-11b and H-12a), 1.55 (1H, m, H-2b), 1.38 (1H, m, H-12b), 1.07 (1H, m, H-14b), 1.20 (1H, td, J = 13.6, 4.0 Hz, H-3b), 1.08 (3H, s, H3-18), 0.97 (3H, s, H3-20); 13C NMR (acetone-d6, 100 MHz) δ 178.2 (C, C-19), 158.5 (C, C-16), 104.0 (CH2, C-17), 83.1 (CH, C-15), 82.7 (CH, C-1), 78.5 (CH, C-7), 51.5 (C, C-8), 49.5 (C, C-10), 44.8 (CH, C-9), 43.6 (C, C-4), 43.0 (CH, C-5), 41.6 (CH, C-13), 36.9 (CH2, C-3), 36.4 (CH2, C-14), 35.2 (CH2, C-12), 31.5 (CH2, C-2), 28.8 (CH3, C-18), 27.8 (CH2, C-6), 20.4 (CH2, C-11), 12.1 (CH3, C-20); HRESIMS m/z 387.2130 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C21H32NaO5, 387.2147).

1-O-Acetyl-15α-hydroxy-15-deoxy-methylgeopyxin A (14):

white amorphous solid; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 5.06 (1H, br s, H-17a), 4.92 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, H-17b), 4.71 (1H, dd, J = 11.5, 4.8 Hz, H-1β), 4.17 (1H, br t, J = 2.4 Hz, H-15), 3.65 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.63 (1H, br s, H-7α), 2.63 (1H, br s, H-13), 2.57 (1H, d, J = 5.1 Hz, D2O exchangeable, OH-15), 2.26 (1H, br s, D2O exchangeable, OH-7), 2.19 (1H, dt, J = 13.9, 3.5 Hz, H-3a), 2.09 (1H, m, H-5), 2.04 (1H, m, H-11a), 2.01 (1H, m, H-6a), 1.98 (3H, s, OAc), 1.91 (1H, m, H-6b), 1.88 (1H, m, H-2a), 1.84 (1H, m, H-9), 1.74 (1H, d, J = 11.4 Hz, H-14a), 1.69 (1H, m, H-2b), 1.66 (1H, m, H-12a), 1.57 (1H, m, H-12b), 1.45 (1H, m, H-12b), 1.24 (1H, m, H-3b), 1.98 (3H, s, OAc),1.13 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.11 (1H, m, H-14b),1.03 (3H, s, H3-20); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 177.5 (C, C-19), 170.2 (C, OCOCH3), 156.4 (C, C-16), 104.8 (CH2, C-17), 84.3 (CH, C-1), 82.2 (CH, C-15), 77.9 (CH, C-7), 51.5 (CH3, OCH3), 48.2 (C, C-4), 45.1 (CH, C-9), 42.9 (C, C-10), 40.6 (CH, C-5), 40.1 (CH, C-13), 35.6 (CH2, C-14), 35.3 (CH2, C-3), 34.0 (CH2, C-12), 28.8 (CH2, C-6), 28.4 (CH3, C-18), 25.7 (CH2, C-2), 21.8 (CH3, OCOCH3), 19.4 (CH2, C-11), 12.0 (CH3, C-20).

Epoxidation of methylgeopyxin A (6):

To a solution of 6 (15.0 mg) in THF (1.0 mL) at 0 °C was added a solution of H2O2 (15%, 15.0 μL) in 1N NaOH (150.0 μL). Ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C. After 3 h, reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10.0 mL), washed with 5% Aq. FeSO4 (5 mL), dried over anhy. Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to give crude products mixture (15.8 mg). This was purified by RP-HPLC [MeCN–H2O (60:40)] to give 16,17-epoxymethylgeopyxin A (15, 8.6 mg, 55%, tR 16.7 min) as a white amorphous solid; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 4.66 (1H, D2O exchangeable, OH-7), 3.83 (1H, dd, J = 2.5, 1.5 Hz, H-7α), 3.65 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.49 (1H, dd, J = 11.5, 4.7 Hz, H-1β), 3.16 (1H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H-17a), 3.06 (1H, dd, J = 16.4, 5.3 Hz, H-11a), 3.03 (1H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H-17b), 2.43 (1H, dd, J = 12.5, 1.2 Hz, H-14a), 2.33 (1H, t, J = 3.8 Hz, H-13), 2.16 (1H, dt, J = 13.9, 3.5 Hz, H-3a), 2.08 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-9), 1.99–1.94 (2H, m, H2-6), 1.93 (1H, m, H-5), 1.89–1.83 (3H, m, H-2a and H2-12), 1.62 (1H, m, H-14b), 1.60 (1H, m, H-2b), 1.59 (H, m, H-11b), 1.22 (1H, dt, J = 13.9, 4.4 Hz, H-3b), 1.15 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.03 (3H, s, H3-20); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 223.8 (C, C-15), 177.7 (C, C-19), 81.6 (CH, C-1), 71.6 (CH, C-7), 63.5 (C, C-16), 54.6 (C, C-8), 53.6 (CH2, C-17), 51.4 (CH3, OMe), 47.3 (CH, C-9), 44.9 (C, C-10), 44.5 (CH, C-5), 42.8 (C, C-4), 35.5 (CH2, C-3), 34.2 (CH, C-13), 32.6 (CH2, C-14), 30.2 (CH2, C-2), 28.3 (CH3, C-18), 27.2 (CH2, C-12), 26.8 (CH2, C-6), 21.5 (CH2, C-11), 11.6 (CH3, C-20); HRESIMS m/z 401.1949 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C21H30NaO6, 401.1940).

Hydrogenation of geopyxin A (1):

To a solution of 1 (2.5 mg) in EtOH (0.5 mL) was added 10% Pd on C (0.5 mg) and stirred under atmosphere of H2 at 25 °C. After 30 min reaction mixture was filtered through a short column of silica gel to give 16,17-dihydrogeopyxin A (16, 2.5 mg, 99%) as a white amorphous solid; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 3.79 (1H, d, J = 2.9 Hz, H-7α), 3.48 (1H, dd, J = 11.1, 4.7 Hz, H-1β), 2.86 (1H, dd, J = 16.1, 5.3 Hz, H-11a), 2.42 (1H, m, H-13), 2.34 (1H, q, J = 6.9 Hz, H-16), 2.31 (1H, dd, J = 13.3, 3.6 Hz, H-14a), 2.13 (1H, dd, J = 11.4, 1.8 Hz, H-3a), 1.97–1.93 (5H, m, H-2a, H2-6, H-5 and H-9), 1.76 (1H, tdd, J = 14.3, 5.9, 2.4 Hz, H-12a), 1.63–1.57 (2H, m, H-2b and H-12b), 1.43 (1H, dd, J = 13.3, 3.7 Hz, H-14b), 1.25 (1H, m, H-3b), 1.22 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.11 (3H, s, H3-20), 1.07 (3H, d, J = 6.9 Hz, H3-17); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 229.9 (C, C-15), 183.6 (C, C-19), 81.8 (CH, C-1), 71.9 (CH, C-7), 53.6 (C, C-8), 48.8 (C, C-16), 47.0 (CH, C-9), 44.7 (CH, C-5), 44.0 (C, C-10), 42.7 (C, C-4), 36.3 (CH2, C-14), 35.3 (CH2, C-3), 34.9 (CH, C-13), 30.1 (CH2, C-2), 28.5 (CH3, C-18), 27.1 (CH2, C-6), 25.3 (CH2, C-12), 20.6 (CH2, C-11), 11.4 (CH3, C-20), 9.7 (CH3, C-17); HRESIMS m/z 373.1987 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C20H30NaO5, 373.1991).

MTT Assay

Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Briefly, approximately 2×104 MDA-MB-231 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. Cells were treated with indicated compounds or combination for 48 h followed by the addition of 20 μl of 2 mg/ml MTT directly into the medium. After incubation (37°C for 3 h), the plate was centrifuged and the medium removed. 100 μl of isopropanol/HCl was added into each well and crystals were dissolved by shaking the plate at room temperature. Absorbance was measured by a plate reader at 570 nm. Triplicate wells were used for each sample and the experiments were repeated at least three times to acquire means and standard deviations.

Live cell fluorescent imaging

iBMK-EGFP-LC3 were seeded in glass bottom 35 mm dishes. 24 h later, cells were either left untreated (NT), treated with 1 µM NaAsO2, or treated with different compounds at corresponding EC50 (based on Table 1) for 4 h. Prior to imaging, cells were gently washed with 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and DMEM without phenol red was added. Images were taken with a Zeiss Observer.Z1 microscope using the Slidebook 4.2.0.11 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc.).

Immunoblot analysis

To detect protein expression, 6×105 cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes. 24 h later, cells were either left untreated or treated with the indicated concentrations of compound 3 or 5 for indicated time. Following treatment, cells were washed in 1X PBS and harvested in Laemmli buffer (31.25mM Tris-Cl, 1.5% SDS, 5% glycerol, 50X β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.05 % bromophenol blue), and boiled for 5 min. Cell lysates were then resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. All immunoblot images were taken using the BioRad Chemidoc system and analyzed using the BioRad Quantity One Software v4.6.1.

mRNA extraction and real-time PCR

6×105 cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes. 24 h later, cells were treated with compound 3 or 5 at corresponding EC50 (based on Table 1) for 16 h. Total mRNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen). 1 µg of RNA for each treatment was used for reverse transcription using an M-MLV-reverse transcriptase (Promega). The detailed primer sequences are as follows:

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| NRF2 | ACACGGTCCACAGCTCATC | TGTCAATCAAATCCATGTCCTG |

| KEAP1 | ACCACAACAGTGTGGAGAGGT | CGATCCTTCGTGTCAGCAT |

| AKR1C1 | GGAGGCCATGGAGAAGTGTA | GCACACAGGCTTGTACCTGA |

| NQO-1 | ATGTATGACAAAGGACCCTTCC | TCCCTTGCAGAGAGTACATGG |

| GCLM | GACAAAACACAGTTGGAACAGC | CAGTCAAATCTGGTGGCATC |

| HMOX-1 | AACTTTCAGAAGGGCCAGGT | CTGGGCTCTCCTTGTTGC |

| GAPDH | CTGACTTCAACAGCGACACC | TGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT |

SYBR Green kit (Kapa) was used and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on the LightCycler 480 system (Roche) as follows: one cycle of initial denaturation (95°C for 4 min), 45 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s), and a cooling period. The data presented are relative mRNA levels normalized to the level of GAPDH, and the value from the untreated cells was set as 1. PCR assays were performed three times with duplicate samples, which were used to determine the means ± standard deviations. The Student t-test was used to evaluate statistically significant differences.

Ubiquitination assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were co-transfected with expression vectors for HA-Ub and NRF2. After 24 h, cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 for 4 h. Cells were harvested in buffer containing 2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 1 mM DTT and immediately boiled. The lysates were then diluted five-fold in buffer without SDS and incubated with an anti-NRF2 antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblot with an antibody against the HA epitope.

Protein half-life

6×105 cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes. 24 h later, cells were either left untreated, or treated with compound 3 or 5 at corresponding EC50 (based on Table 1) for 16 h. 50 μM cycloheximide was added to block de novo protein synthesis. Total cell lysates were collected at different time points and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the antibodies against NRF2 and GAPDH. The relative intensity of the bands was quantified using the ChemiDoc CRS gel documentation system and Quantity One software from BioRad (Hercules, CA).

Reporter assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with either wild type KEAP1 or KEAP1-C151S, along with NQO-1-ARE firefly luciferase and TK-Renilla luciferase reporters. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were left untreated or treated with SFN (2 μM), As (1 μM), or compound 3 or 5 (at corresponding EC50 concentrations) for 16 h. The cells were then lysed for analysis of the reporter gene activity using the Promega dual-luciferase reporter gene assay system.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSES

The results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0. Skewness and kurtosis were analyzed to assure normal distribution. If Z-score for both skewness and kurtosis was within the range of −1.96 to 1.96, the data were considered to follow normal distribution. Unpaired Student’s t-tests were applied to compare the means of two groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction was used to compare the means of three or more groups. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses can be found in the figures and the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-NRF2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-13032, RRID:AB_2263168 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-KEAP1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-15246, RRID:AB_2132638 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-AKR1C1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-166297, RRID:AB_2224281 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NQO-1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-32793, RRID:AB_628036 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HO-1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-136960, RRID:AB_2011613 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GCLM | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-55586, RRID:AB_831789 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-32233, RRID:AB_627679 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA | Biolegend | Cat# 901502, RRID:AB_2565007 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG-HRP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A-0545, RRID:AB_257896 |

| Bovine polyclonal anti-goat IgG-HRP | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-2350, RRID:AB_634811 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-mouse IgG-HRP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A-9044, RRID:AB_258431 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α Competent Cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 18265017 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| geopyxin analog 1 (Compound 1) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 2 (Compound 2) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 3 (Compound 3) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 4 (Compound 4) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 5 (Compound 5) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 6 (Compound 6) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 7 (Compound 7) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 8 (Compound 8) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 9 (Compound 9) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 10 (Compound 10) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 11 (Compound 11) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 12 (Compound 12) | Wijeratne et al., 2012 | https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np200769q |

| geopyxin analog 13 (Compound 13) | This study | N/A |

| geopyxin analog 14 (Compound 14) | This study | N/A |

| geopyxin analog 15 (Compound 15) | This study | N/A |

| geopyxin analog 16 (Compound 16) | This study | N/A |

| Sulforaphane (SFN) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S6317 |

| tert-Butylhydroquinone (tBHQ) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 112941 |

| 3–4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazo-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 111714 |

| Isopropyl Alcohol | EMD Millipore | Cat# PX1834 |

| Hydrochloric acid (HCl) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 320331 |

| Sodium (meta)arsenite (NaAsO2) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S7400 |

| Tris | AMRESCO | Cat# 0497 |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP166–500 |

| Glycerol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G9012 |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M3148 |

| Bromophenol Blue | Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP115–25 |

| TRIzol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15596018 |

| MG132 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 474787 |

| Sodium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP358–1 |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Golden Biotechnology | Cat# DTT50 |

| Cycloheximide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C7698 |

| Chloroform (CHCl3) | Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP1145–1 |

| Acetone | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A11–1 |

| Sulfuric Acid (H2SO4) | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A300C-212 |

| Acetic Acid (HOAc) | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A38S-500 |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A412–500 |

| Cerium(III) chloride heptahydrate (CeCl3.7H2O) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 228931 |

| Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 452882 |

| Ethyl acetate (EtOAc) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 270989 |

| Sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 239313 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase | Promega | Cat# M1701 |

| KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR kits | Kapa Biosystems | Cat# KK4611 |

| Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System | Promega | Cat# E1910 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| iBMK-EGFP-LC3 | Dr. Eileen White’s lab, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey | N/A |

| MDA-MB-231 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-26™ |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for NRF2, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Primers for KEAP1, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Primers for NQO-1, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Primers for GCLM, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Primers for HMOX1, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Primers for AKR1C1, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Primers for GAPDH, see Methods section | This study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pcDNA3-KEAP1-WT | Lau A, et al. 2013 | https://mcb.asm.org/content/33/12/2436.long |

| pcDNA3-KEAP1-C151S | Lau A, et al. 2013 | https://mcb.asm.org/content/33/12/2436.long |

| pCI-NRF2 | Tao S, et al. 2017 | https://mcb.asm.org/content/37/8/e00660–16 |

| pCMV-HA-Ub | Tao S, et al. 2017 | https://mcb.asm.org/content/37/8/e00660–16 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Slidebook 4.2.0.11 software | Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc. | N/A |

| Quantity One Software v4.6.1. | Bio-Rad | N/A |

| SPSS Statistics Software v17.0 | IBM | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Fetal bovine serum | VWR | Cat# 97068–085 |

| L-glutamine | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 25030081 |

| Penicillin-streptomycin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15140122 |

| Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) | Corning | Cat# MT-15–010-CV |

| Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) | Corning | Cat# MT-10–013-CV |

SIGNIFICANCE.

The activation of the transcription factor, NRF2, leads to the expression of a series of cellular protective genes that combat oxidative and toxicant stresses, protecting the organism from environmental damage. However, it has been revealed that certain compounds found in many of the foods we eat naturally activate the NRF2 pathway and that these can have salubrious benefits. Attempts have been made to harness these benefits by discovering and developing compounds to intentionally activate NRF2. However, most of the reported compounds are reactive, nonspecific electrophiles that have not shown the desired clinical benefits, which has led to the proposal of using reversible inhibitors of the NRF2-KEAP1 interaction. This work reports on the evaluation of ent-kaurane natural products as NRF2 activators. Our unique chemistry related to this class of compounds allowed for a comparison between covalent and non-covalent compounds with a conserved core structure. For the first time, we demonstrate the heightened protective properties of non-covalent NRF2 activators in cell lines challenged with the environmental toxicant sodium arsenite or the cancer chemotherapeutic, cisplatin.

HIGHLIGHTS.

The ent-kaurane diterpenoids, geopyxins activate the NRF2 pathway

Geopyxin F activated NRF2 in A KEAP1-dependent but Cys151 independent manner

Geopyxin F conferred greater protection than a Cys151 dependent analog, geopyxin C

The first comparison between iso-steric covalent and non-covalent NRF2 activators

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support for this work from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant ES023758 to EC and DDZ), the National Cancer Institute (Grant R01 CA90265 to AALG) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant P41 GM094060 to AALG) are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study.

REFERENCES

- Baird L, Lleres D, Swift S, and Dinkova-Kostova AT (2013). Regulatory flexibility in the Nrf2-mediated stress response is conferred by conformational cycling of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 15259–15264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand HC, Schaap M, Baird L, Georgakopoulos ND, Fowkes A, Thiollier C, Kachi H, Dinkova-Kostova AT, and Wells G (2015). Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Triazole Derivatives That Induce Nrf2 Dependent Gene Products and Inhibit the Keap1–Nrf2 Protein–Protein Interaction. Journal of medicinal chemistry 58, 7186–7194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, and Kong AN (2004). Dietary chemopreventive compounds and ARE/EpRE signaling. Free radical biology & medicine 36, 1505–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan SB, Gordan JD, Jin J, Harper JW, and Diehl JA (2004). The Keap1-BTB protein is an adaptor that bridges Nrf2 to a Cul3-based E3 ligase: oxidative stress sensing by a Cul3-Keap1 ligase. Molecular and cellular biology 24, 8477–8486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega MR, Dodson M, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2016). NRF2-targeted therapeutics: New targets and modes of NRF2 regulation. Curr Opin Toxicol 1, 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Fahey JW, Kostov RV, and Kensler TW (2017). KEAP1 and Done? Targeting the NRF2 Pathway with Sulforaphane. Trends in food science & technology 69, 257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson M, de la Vega MR, Harder B, Castro-Portuguez R, Rodrigues SD, Wong PK, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2018a). Low-level arsenic causes proteotoxic stress and not oxidative stress. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 341, 106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson M, Liu P, Jiang T, Ambrose AJ, Luo G, Rojo de la Vega M, Cholanians AB, Wong PK, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2018b). Increased O-GlcNAcylation of SNAP29 drives arsenic-induced autophagic dysfunction. Molecular and cellular biology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Egner PA, Chen JG, Wang JB, Wu Y, Sun Y, Lu JH, Zhu J, Zhang YH, Chen YS, Friesen MD, et al. (2011). Bioavailability of sulforaphane from two broccoli sprout beverages: Results of a short term, cross-over clinical trial in Qidong, China. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 4, 384–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Doan A, and Hybertson BM (2014). The clinical potential of influencing Nrf2 signaling in degenerative and immunological disorders. Clinical pharmacology : advances and applications 6, 19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer A, Waschbisch A, Kuhbandner K, Bayas A, Lee D-H, Duscha A, Haghikia A, Gold R, and Linker RA (2018). The NRF2 pathway as potential biomarker for dimethyl fumarate treatment in multiple sclerosis. Annals of clinical and translational neurology 5, 668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder B, Jiang T, Wu T, Tao S, Rojo de la Vega M, Tian W, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2015). Molecular mechanisms of Nrf2 regulation and how these influence chemical modulation for disease intervention. Biochemical Society transactions 43, 680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, and Dinkova-Kostova AT (2014). The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends in biochemical sciences 39, 199–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DS, Kurzrock R, Supko JG, He X, Naing A, Wheler J, Lawrence D, Eder JP, Meyer CJ, Ferguson DA, et al. (2012). A phase I first-in-human trial of bardoxolone methyl in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphomas. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 18, 3396–3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, et al. (1997). An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 236, 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong WS, Jun M, and Kong AN (2006). Nrf2: a potential molecular target for cancer chemoprevention by natural compounds. Antioxidants & redox signaling 8, 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Harder B, Rojo de la Vega M, Wong PK, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2015). p62 links autophagy and Nrf2 signaling. Free radical biology & medicine 88, 199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z-Y, Lu M-C, Xu LL, Yang T-T, Xi M-Y, Xu X-L, Guo X-K, Zhang X-J, You Q-D, and Sun H-P (2014). Discovery of Potent Keap1–Nrf2 Protein–Protein Interaction Inhibitor Based on Molecular Binding Determinants Analysis. Journal of medicinal chemistry 57, 2736–2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T, Igarashi K, and Yamamoto M (2004). Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Molecular and cellular biology 24, 7130–7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak MK, and Kensler TW (2010). Targeting NRF2 signaling for cancer chemoprevention. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 244, 66–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, and Kensler TW (2004). Chemoprevention through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway by phase 2 enzyme inducers. Mutation research 555, 133–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, Wang XJ, Zhao F, Villeneuve NF, Wu T, Jiang T, Sun Z, White E, and Zhang DD (2010). A noncanonical mechanism of Nrf2 activation by autophagy deficiency: direct interaction between Keap1 and p62. Molecular and cellular biology 30, 3275–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nioi P, McMahon M, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, and Hayes JD (2003). Identification of a novel Nrf2-regulated antioxidant response element (ARE) in the mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene: reassessment of the ARE consensus sequence. The Biochemical journal 374, 337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergola PE, Krauth M, Huff JW, Ferguson DA, Ruiz S, Meyer CJ, and Warnock DG (2011a). Effect of bardoxolone methyl on kidney function in patients with T2D and Stage 3b-4 CKD. American journal of nephrology 33, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergola PE, Raskin P, Toto RD, Meyer CJ, Huff JW, Grossman EB, Krauth M, Ruiz S, Audhya P, Christ-Schmidt H, et al. (2011b). Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. The New England journal of medicine 365, 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada P, Rojo AI, Chowdhry S, McMahon M, Hayes JD, and Cuadrado A (2011). SCF/{beta}-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Molecular and cellular biology 31, 1121–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo de la Vega M, Dodson M, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2016). NRF2-targeted therapeutics: New targets and modes of NRF2 regulation. Current Opinion in Toxicology 1, 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen T, Jiang T, Long M, Chen J, Ren DM, Wong PK, Chapman E, Zhou B, and Zhang DD (2015). A Curcumin Derivative That Inhibits Vinyl Carbamate-Induced Lung Carcinogenesis via Activation of the Nrf2 Protective Response. Antioxidants & redox signaling 23, 651–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepler B, Nash C, Smith C, Dimarco A, Petty J, and Szewciw S (2012). Update on potential drugs for the treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Clinical therapeutics 34, 1237–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, and Yamamoto M (2015). Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free radical biology & medicine 88, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, and Yamamoto M (2017). Stress-sensing mechanisms and the physiological roles of the Keap1-Nrf2 system during cellular stress. The Journal of biological chemistry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tao S, Liu P, Luo G, Rojo de la Vega M, Chen H, Wu T, Tillotson J, Chapman E, and Zhang DD (2017). p97 Negatively Regulates NRF2 by Extracting Ubiquitylated NRF2 from the KEAP1-CUL3 E3 Complex. Molecular and cellular biology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tao S, Park SL, Rojo de la Vega M, Zhang DD, and Wondrak GT (2015). Systemic administration of the apocarotenoid bixin protects skin against solar UV-induced damage through activation of NRF2. Free radical biology & medicine 89, 690–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao S, Zheng Y, Lau A, Jaramillo MC, Chau BT, Lantz RC, Wong PK, Wondrak GT, and Zhang DD (2013). Tanshinone I activates the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response and protects against As(III)-induced lung inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Antioxidants & redox signaling 19, 1647–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimmulappa RK, Mai KH, Srisuma S, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, and Biswal S (2002). Identification of Nrf2-regulated genes induced by the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane by oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer research 62, 5196–5203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MC, and Cooper ME (2011). Diabetes: bardoxolone improves kidney function in type 2 diabetes. Nature reviews Nephrology 7, 552–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong KI, Katoh Y, Kusunoki H, Itoh K, Tanaka T, and Yamamoto M (2006a). Keap1 recruits Neh2 through binding to ETGE and DLG motifs: characterization of the two-site molecular recognition model. Molecular and cellular biology 26, 2887–2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong KI, Kobayashi A, Katsuoka F, and Yamamoto M (2006b). Two-site substrate recognition model for the Keap1-Nrf2 system: a hinge and latch mechanism. Biological chemistry 387, 1311–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong KI, Padmanabhan B, Kobayashi A, Shang C, Hirotsu Y, Yokoyama S, and Yamamoto M (2007). Different electrostatic potentials define ETGE and DLG motifs as hinge and latch in oxidative stress response. Molecular and cellular biology 27, 7511–7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve NF, Lau A, and Zhang DD (2010). Regulation of the Nrf2-Keap1 antioxidant response by the ubiquitin proteasome system: an insight into cullin-ring ubiquitin ligases. Antioxidants & redox signaling 13, 1699–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne EM, Bashyal BP, Liu MX, Rocha DD, Gunaherath GM, U’Ren JM, Gunatilaka MK, Arnold AE, Whitesell L, and Gunatilaka AA (2012). Geopyxins A-E, ent-kaurane diterpenoids from endolichenic fungal strains Geopyxis aff. majalis and Geopyxis sp. AZ0066: structure-activity relationships of geopyxins and their analogues. Journal of natural products 75, 361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wondrak GT, Cabello CM, Villeneuve NF, Zhang S, Ley S, Li Y, Sun Z, and Zhang DD (2008). Cinnamoyl-based Nrf2-activators targeting human skin cell photo-oxidative stress. Free radical biology & medicine 45, 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MH, Bryan HK, Copple IM, Jenkins RE, Chiu PH, Bibby J, Berry NG, Kitteringham NR, Goldring CE, O’Neill PM, et al. (2016). Design and Synthesis of Irreversible Analogues of Bardoxolone Methyl for the Identification of Pharmacologically Relevant Targets and Interaction Sites. Journal of medicinal chemistry 59, 2396–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Zhao F, Gao B, Tan C, Yagishita N, Nakajima T, Wong PK, Chapman E, Fang D, and Zhang DD (2014). Hrd1 suppresses Nrf2-mediated cellular protection during liver cirrhosis. Genes & development 28, 708–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L-L, Zhu J-F, Xu X-L, Zhu J, Li L, Xi M-Y, Jiang Z-Y, Zhang M-Y, Liu F, Lu M. c., et al. (2015). Discovery and Modification of in Vivo Active Nrf2 Activators with 1,2,4-Oxadiazole Core: Hits Identification and Structure–Activity Relationship Study. Journal of medicinal chemistry 58, 5419–5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, and Kensler T (2005). Nrf2 as a target for cancer chemoprevention. Mutation research 591, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DD (2006). Mechanistic studies of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway. Drug metabolism reviews 38, 769–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DD (2013). Bardoxolone brings Nrf2-based therapies to light. Antioxidants & redox signaling 19, 517–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DD, and Hannink M (2003). Distinct cysteine residues in Keap1 are required for Keap1-dependent ubiquitination of Nrf2 and for stabilization of Nrf2 by chemopreventive agents and oxidative stress. Molecular and cellular biology 23, 8137–8151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DD, Lo SC, Cross JV, Templeton DJ, and Hannink M (2004). Keap1 is a redox-regulated substrate adaptor protein for a Cul3-dependent ubiquitin ligase complex. Molecular and cellular biology 24, 10941–10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kensler TW, Cho CG, Posner GH, and Talalay P (1994). Anticarcinogenic activities of sulforaphane and structurally related synthetic norbornyl isothiocyanates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91, 3147–3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang C, Narayanapillai S, Zhang W, Sham YY, and Xing C (2014). Rapid Identification of Keap1–Nrf2 Small-Molecule Inhibitors through Structure-Based Virtual Screening and Hit-Based Substructure Search. Journal of medicinal chemistry 57, 1121–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.