Abstract

We calculate the polarization portion of electrostatic interactions at the atomic scale using quantum mechanical methods such as density functional theories (DFT) and the coupled cluster approach, and using classical methods such as a surface charge method and a polarizable force field. The agreement among various methods is investigated. Using the coupled clusters method CCSD(T) with large basis sets as the reference, we find that for systems comprising two to six atoms and ions in S-states the classical surface charge method performs much better than commonly used DFT methods with moderate basis sets such as B3LYP/6–31G(d,p). The remarkable performance of the classical approach comes as a surprise. The present results indicate that the use of a rigorous formalism of classical electrostatics can be better justified for determining molecular interactions at intermediate distances than some of the widely used methods of quantum chemistry.

PACS numbers: 41.20.Cv,32.10.Dk, 87.10.Tf

Quantum theory was developed to explain and understand various atomic scale phenomena that cannot be explained with classical methods. In light of its exceptional success, it is generally assumed that at atomic scale quantum theory is needed for a quantitatively accurate description. However, quantum calculations quickly become computationally expensive as the number of atoms in a system grows. Consequently, there is a desire to apply classical theories as widely as possible. Electrostatic interactions are ubiquitous and parallel conceptually in quantum and classical physics. Therefore the question naturally arises as to whether and to what extent classical electrostatics can be used to accurately model the interaction among atoms and molecules.

To address this question, we numerically examined the limit of applicability of classical physics for describing the electrostatic interactions among several atoms and ions in S-states. Comparing interaction energies calculated using high-level quantum mechanical methods with the results of a rigorous classical electrostatic approach, we conclude that a classical surface charge method applied to a simple model of dielectric spheres can be used to reproduce the reference quantum interaction energies with accuracy comparable to that of some widely used quantum methods.

Finding the extent of applicability of classical electrostatics can simplify the treatments for a wide variety of systems that are too complex for a purely quantum mechanical approach, including liquids and solids [1, 2], ions [3], liquid crystals [4], polymers [5], and biomolecules [6]. As an example, in biomolecular systems electrostatics, through the mid- and long-range interactions, essentially drives docking of biomolecules, the first step in a cascade of physical interactions underlying biological processes.

One way to model the electrostatic effects is by assigning point charges (and occasionally higher moments [7]) to various parts of the system [8]. However, computing the electrostatic interaction with the required accuracy often cannot be achieved without accounting for multibody polarization effects. Another systematic approach for incorporating classical electrostatic interactions into simulations is the method of polarizable force fields. Polarizable force fields introduce both fixed and inducible electrostatic moments at various positions in the system and determine their values in a self-consistent fashion[9–11]. This scheme provides a meaningful way of capturing mutual polarization that is inherently present in the quantum mechanical treatment and is a natural approach when all parts of the system (e.g., water molecules) are explicitly included.

A commonly employed strategy to reduce computational cost in biomolecular simulations is to regard the solvent (water) and the solutes (e.g., proteins and nucleic acids) as bulk dielectrics with well defined surfaces and fixed charges assigned to various positions within the solutes [12]. These implicit solvent methods require solution of the Poisson (or Poisson-Boltzmann) equation [13], either directly or by using a surface charge method. While a theoretically rigorous and numerically stable calculation of electrostatic interactions even within this model can be quite difficult, the calculation is expected to be more tractable than a polarizable force field or a full quantum calculation.

Of course, the classical model of bulk dielectric has certain obvious limitations: there is no classical interaction among objects in the absence of charges; the classical electrostatic interaction does not produce an equilibrium separation and thus cannot describe chemical bonds; the touching of the dielectric bodies prevents the classical model from being applied at even shorter distances. In this letter, however, we are interested in assessing the accuracy of classical physics for describing the electrostatic interactions among atomic-scale charged dielectric bodies at intermediate distances.

Atoms and ions in S-states, not covalently bonded, present a convenient test system for collating the classical and quantum descriptions since their energies can be obtained with high accuracy. On the classical side, a formalism was recently developed [14] which allows determining with controllable accuracy the electrostatic energy for an arbitrary set of dielectric spheres and charges. On the quantum side, the calculations are also streamlined and are less sensitive to the choice of computational details. Reviews of the large body of previous calculations and comparisons with available experimental data [15–24] suggest that the coupled cluster approach combined with moderately large basis sets is adequate for reproducing the binding energies and interaction potentials between atoms and ions in Sstates with the accuracy of several per cent or better. Thus the coupled cluster calculations are used as our reference points.

The classical model of charged dielectric spheres mentioned above requires input parameters, namely the dielectric constant ϵ and the radius R of each sphere. Since the concept of dielectric constant is not precisely defined for individual atoms, we seek a connection with a related quantity, the atomic polarizability α, which is simply the proportionality constant between the induced dipole of an atom and electric field to which it is subjected. With α can be directly measured via the Stark effect. In the quantum calculation [25], the induced dipole is given by a summation over dipole matrix elements between the ground and excited states of the atom. In the classical case [26], the induced dipole of a dielectric sphere can be expressed via its radius R and dielectric constant ϵ:

Thus the combination R3(ϵ − 1)/(ϵ + 2) is, by definition, the polarizability of the dielectric sphere:

| (1) |

Condition (1) defines the minimum radius of the sphere to be (α)1/3 in order to satisfy the condition ϵ > 1. For a test case of singly charged Al ions, whose polarizability is 24.65 using CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ (24.4 using CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV5Z and 24.2 from the sum rule [27, 28]), the minimum ionic radius is 1.54 Å.

With , eq. (1) relates ϵ and R. As we will see later, the classical interaction energy is not sensitive to the choice of R and ϵ provided that eq. (1) holds. In particular, the choice of R = 2Å yields a reasonable value of ϵ = 3.52 and an excellent agreement with the reference quantum mechanical calculations. The parameters for the many-sphere classical formalism are thus obtained by considering only a single atom (sphere) at a time.

For two atoms or ions separated by a sufficiently large distance L so that a covalent bond is not formed, the total energy of the system can be partitioned as

| (2) |

where εA and εB are the self energies of ions/atoms A and B, qA and qB are their corresponding charges, and U(L), the polarization portion of the interaction energy, is the focus of our interest. For two charged particles the 1/L term evidently dominates. However, the importance of the polarization terms increases as the density of polarizable particles subject to an electric field increases [29]. It increases even further for charged particles embedded in an environment of highly polarizable neutral molecules (e.g, for proteins solvated in water) [30].

For large L, one may use 1/L as the perturbation parameter and expand the polarization portion of the interaction energy U(L) in powers of 1/L. However, we do not use such an expansion to calculate any of the interaction energies. Nevertheless, it is instructive to compare the expansion structure and the meaning of the coefficients in quantum and classical cases.

For two quantum particles in S-states, U(L) can be expanded as [31]:

| (3) |

where αA and αB are the respective atomic polarizabilities.

The 1/L6 term of the remainder should contain both the induced quadrupole–point charge interactions and the London dispersion energy (i.e., the van der Waals interaction). In the case of many atoms, the meaning of the coefficients would not be so simple but the L dependence would remain the same if all pairwise separations are L.

In the classical case a rigorous and effective method for determining the energy of interaction among arbitrary number of charged and neutral dielectric spheres was developed relatively recently [14]. This method affords controllable accuracy in calculating interaction energy among multiple dielectric spheres, eliminating questions about the numerical precision. For the special case of two spheres, this method yields

| (4) |

where qA, qB, RA, and RB are the net charges and the radii of the respective spheres A and B. The coefficients Q are found as the solution of the linear system

Similar to the quantum case (3), the expansion of the classical U(L) starts with 1/L4:

| (5) |

where is the classical analogue of dipole polarizability, see equality (1), and is the classical analogue of quadrupole polarizability[36] for dielectric sphere A(B).

Evidently, the first order terms in the quantum and classical treatments are exactly the same. This shows that the dielectric spheres model correctly captures the dominant electrostatic interactions in expansion (3) if either of the interacting particles has a net charge. Similarly to the quantum case, the induced quadrupole–point charge interaction varies as 1/L6. However, the spontaneous induced dipole–induced dipole (van der Waals) interaction that also varies as 1/L6 is absent. Further, when both spheres are charged, the induced dipole–induced dipole interaction emerges and varies as 1/L7. The reason is simple. Each dipole strength is proportional to the electric field strength ∝ 1/L2 and the interaction energy between dipoles varies as 1/L3. This classical effect should not be confused with the Casimir-Polder retardation[37].

In fig. 1 we plot the ratio for several interacting pairs of ions and atoms. Note that quickly decreases with the separation L and the leading term in expansion (3) provides the bulk of the polarization energy U(L), down to very short distances. For atom-ion pairs the remainder of (3) seems to be more important than for atom-atom and ion-ion pairs, but is still small.

FIG. 1:

(Color online) The ratio . The calculations are done at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ with no frozen core orbitals for Ar-Al+ (green squares), Al+-Al+ (red triangles), Ne-Al+ (blue circles), and Ne-Ne (black asterisks) pairs. Note that for the Ne-Ne pair, U(L) = −C6/L6 − C8/L8 − C10/L10 − ⋯ with the coefficients obtained by fitting U(L) in inverse powers of L. The remainder is simply U(L) + C6/L6.

Thus, one might be tempted to conclude that in a general multi-particle situation, a good approximation to the polarization portion of the electrostatic interaction energy could be achieved by calculating pairwise interactions and retaining only the leading term in the expansion over inverse separation. Unfortunately, such two-body interaction terms can result in significant errors because they represent neither the leading terms in a full, self-consistent quantum formalism, nor those in a full, self-consistent classical formalism. To demonstrate this we plot in fig. 2 the surface charge (solid black line) induced at the ‘equator’ (θ = π/2) of one of three Al ions forming an equilateral triangle with side of length 4 Å calculated using the general classical formalism mentioned above [14]. The induced surface charge is concentrated in the direction of the triangle’s center (corresponding to the angle ϕ = π). For the pairwise approximation, one retains only the leading term in eqs. (3) and (5), leading to a very broad, symmetric charge distribution which in turn results in a 30.3% error in the polarization portion of the interaction energy. Thus, pairwise approximations cannot be used for obtaining reliable (classical) charge distributions and (classical and quantum) interaction energies.

FIG. 2:

(Color online) The non-monopole surface charge density, in units of electron charge per square Bohr radius, along the equator of one three Al ions forming an equilateral triangle of side 4 Å. The coordinate system is chosen so that the angle ϕ = π points to the center of the equilateral triangle. The solid black line is the exact many-body classical result computed up to l = 9, and the dashed blue line is the sum of pairwise classical results computed only to l = 1.

Currently, an accurate and consistent computation of electrostatic interactions by methods of quantum mechanics appears to be too arduous for practical use. Even properties associated with single atoms such as polarizability require high level quantum methods and often with variable results [38]. Computing accurate quantum mechanical interaction potentials, especially between a neutral atom and an ion, is computationally even more demanding. For example, the experimental binding energy of the Al+-Ar complex is 982.3±5 cm−1 [21, 23]. The complete basis set limit combined with the coupled cluster method CCSD(T) calculation [15] yields 997 cm−1, off by about 1.5%, while the quintuple-ζ aug-cc-pV5Z basis set gives error of about 6%. Fortunately, the error in the tail of the interaction potential, away from the equilibrium distance, is much smaller. At distance 4 Å, the difference between the energies obtained in the aug-cc-pV5Z and the aug-cc-pVTZ basis sets is less than 4 % for the Al+-Ar interaction and a mere 1 % for the Al+-Al+ interaction potential.

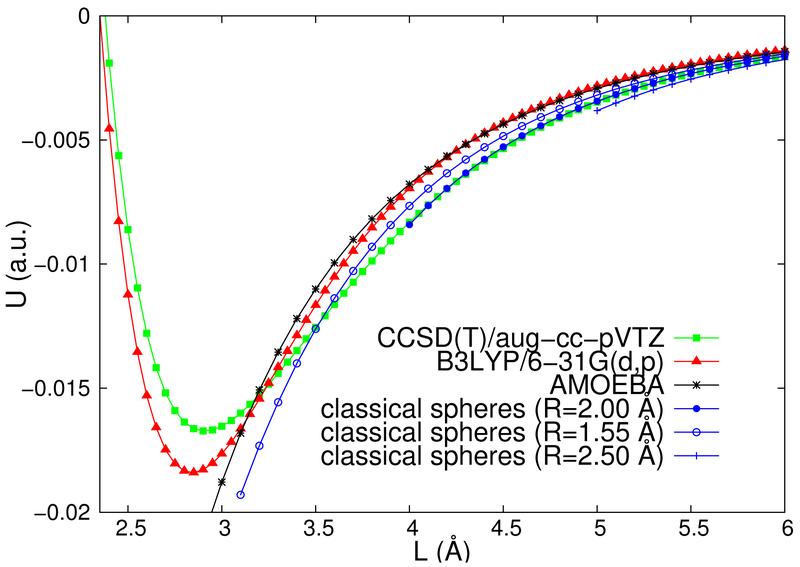

Let us now examine whether the classical dielectric model will permit a relatively quick and reliable way to get reasonable estimates for the polarization part of the interactions. In fig. 3, we compare various U(L) curves obtained with different methods for an Al+-Al+ pair. The green line with squares denotes our reference curve, calculated using the coupled cluster method CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ with no frozen orbitals. The red line with triangles is obtained at a standard DFT level of B3LYP/6–31G(d,p). The well in the B3LYP potential [39] is deeper by about 10% and the interaction energies are off by 16% and 19% at the separations of 4 and 5 Å, respectively. The black line with asterisks in fig. 3 is the interaction potential calculated with a polarizable force field [40].

FIG. 3:

(Color online) The polarization portion of the interaction energy U(L), in atomic units, for Al+-Al+. The calculations are done with the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ with no frozen core orbitals method (green squares), the density functional theory at the B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) level (red triangles), and using the AMOEBA polarizable force field within TINKER 7.1 [11] (black asterisks). For the rigorous classical formalism for two dielectric spheres, three blue symbols, solid circles, open circles, and “+”s, are used respectively for three choices of parameters: (ϵ = 3.52, R = 2 Å), (ϵ = 154.96, R = 1.55 Å), and (ϵ = 1.915, R = 2.5 Å).

The classical model of dielectric spheres (shown with solid circles, open circles, and “+”s in fig. 3), as expected, completely fails to predict the existence of the well in the polarization portion of the interaction potential. Moreover, the classical curves have to be cut at L = 2R, where the two dielectric spheres of the chosen radius R touch. However, the rigorous classical formalism of two dielectric spheres (4) works astoundingly well at large and even at moderate distances. For R = 2 Å, the classical U(L) is practically indistinguishable from the high level quantum computation for L > 4 Å; the classical interaction energies are off by mere 1 % at 4 and 5 Å. It is also important to note that the results of the classical formalism are not sensitive to the choice of the sphere’s radius and dielectric constant, as long as (1) is satisfied. As an illustration, we plot in fig. 3 two other, extreme, choices of parameters: a highly polarizable (ϵ = 154.96, R = 1.55 Å) case shown in blue open circles, and an almost unpolarizable (ϵ = 1.915, R = 2.5 Å) case shown in blue “+”s. Interpolating these three curves, it appears that any curve with parameters obeying eq. (1) will trace the reference potential better than common DFT methods.

The advantage of the classical dielectric spheres model persists as the number of particles in the system increases. To illustrate, in table I for n = 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 Al+ ions we provide the errors of the polarization energies as measured against the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ method. The three ions are located at the vertices of an equilateral triangle. The four ions are located at the vertices of a regular tetrahedron. The five ions are located at the vertices of two stacked regular tetrahedrons. Finally, the six ions are located at the vertices of a regular octahedron. The accuracy of each model is somewhat dependent on the spatial arrangement of the ions. For example, the error of the dielectric spheres model for Ln.n. = 5Å is 6% for two stacked regular tetrahedrons and 3.9% for a center-filled tetrahedron (also n = 5). For references, the error changes from 8.3% (9.0%) to 7.1% (12.8%) when using B3LYP/aug-cc-pV5Z (AMOEBA). Consequently, it is not surprising that the behavior of the accuracy is not monotonic as the systems grow larger.

Table I:

Relative errors in the polarization portion of the interaction energies for clusters of n singly charged Al ions (n = 2…6). Results for several values of Ln.n., the distance between nearest neighbors, are shown. The interaction energies calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ level are used as the reference points. The parameters for the dielectric sphere model are R = 2 Å, ϵ = 3.52.

| n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 4 | n = 5 | n = 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln.n. = 4 Å | |||||

| B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | 16.4 % | 13.9 % | 12.3 % | 11.9 % | 13.5 % |

| B3LYP/aug-cc-pV5Z | 6.9% | 6.5% | 6.5 % | 6.8% | 5.8% |

| pairwise | 9.2% | 30.3 % | 41.8 % | 46.4 % | 51.9 % |

| AMOEBA force field | 18.5 % | 12.8 % | 9.5% | 9.2% | 9.4% |

| dielectric spheres | –1.1 % | 3.3% | 5.6% | 6.1% | 8.1% |

| Ln.n. = 5 Å | |||||

| B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | 18.5 % | 14.8 % | 12.5 % | 11.7 % | 10.3 % |

| B3LYP/aug-cc-pV5Z | 12.2 % | 10.0 % | 8.8% | 8.3% | 7.7% |

| pairwise | 11.0 % | 35.3 % | 48.9 % | 52.6 % | 57.4 % |

| AMOEBA force field | 15.9 % | 12.0 % | 9.9% | 9.0% | 7.1% |

| dielectric spheres | 1.0% | 4.3% | 6.1% | 6.0% | 5.9% |

| Ln.n. = 7 Å | |||||

| B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | 10.5 % | 8.4% | 7.3% | 7.6% | 6.3% |

| B3LYP/aug-cc-pV5Z | 6.9% | 5.6% | 5.0% | 5.4% | 4.5% |

| pairwise | 5.5% | 34.6 % | 49.7 % | 55.3 % | 60.6 % |

| AMOEBA force field | 7.5% | 5.4% | 4.4% | 4.7% | 3.2% |

| dielectric spheres | –1.2 % | 0.6% | 1.7% | 2.5% | 2.2% |

| Ln.n. = 10 Å | |||||

| B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | 6.8% | 5.6% | 5.4% | 5.8% | 4.8% |

| B3LYP/aug-cc-pV5Z | 5.0% | 4.1% | 4.1% | 4.6% | 3.8% |

| pairwise | 3.2% | 34.4 % | 50.3 % | 55.7 % | 61.4 % |

| AMOEBA force field | 3.9% | 2.8% | 2.3% | 2.8% | 1.7% |

| dielectric spheres | –0.5 % | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.6% | 1.1% |

As noted, the importance of the polarization portion of the electrostatic energy increases with the number of particles in the system. For our test system of n Al+ ions using both CCSD(T) and the dielectric sphere model, when n increases from 2 to 6 the ratio of the polarization portion of the energy to the direct Coulomb energy increases from ≈6% to ≈10% (Ln.n. = 4 Å). If these six Al+ ions are embedded in a medium with the dielectric constant of 80, the ratio rises to 33% when using the dielectric sphere model.

It is striking that the classical interaction energies of many-atom systems are so accurate given that only the atomic polarizability (a single atom property) is used as the input. This unexpectedly good performance can be attributed to the essentially many-body nature of the solution of Poisson’s equation capturing the mutual polarization among interacting particles. In order to obtain a good agreement between the quantum calculations and the experimental data, one needs to perform rather intensive quantum calculations using large basis sets. Smaller basis sets, as well as less advanced quantum methods, are not well suited for capturing the mutual polarization of atoms and molecules taking place at intermediate distances. This circumstance makes the success of the surface charge model even more encouraging.

To conclude, our present results imply that the use of a rigorous formalism of classical electrostatics can be better justified for determining atomic interactions at intermediate distances than some of the widely used methods of quantum chemistry.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Library of Medicine. We thank the administrative group of the National Institutes of Health Biowulf Clusters, where most of the computational tasks were carried out using the Gaussian 09 software package [33] and TINKER 7.1 [11].

References

- [1].Allen MP and Tildesley DJ, Computer Simulation of Liquids (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frenkel D and Smit B, Understanding Molecular Simulation (Academic Press, San Diego, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Salanne M and Madden PA, Mol. Phys 109, 2299 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wilson MR, Int. Rev. Phys. Chem, 24 421 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- [5].Glotzer SC and Paul W, Annu. Rev. Mater. Res 32 401 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cisneros GA, Karttunen M, Reni P and Sagui C, Chem. Rev 114 779 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Solovyov IA, Yakubovich AV, Solovyov AV and Greiner W, Phys. Rev. E 75 051912 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brooks BR et al. , J. Comput. Chem 30 1545 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gray F, Phys. Rev 7 472 (1916). [Google Scholar]

- [10].Thole BT, Chem. Phys 59 341 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- [11].Laury ML, Wang L-P, Pande VS, Head-Gordon T and Ponder JW, J. Phys. Chem. B 119 9423 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cramer CJ and Truhlar DG, Chem. Rev 99 2161 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lu BZ, Zhou YC, Holst MJ and McCammon JA, Commun. Comput. Phys 3 973 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Doerr TP and Yu Y-K, Phys. Rev. E 73 061902 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gardner AM, Gutsmiedl KA, Wright TG, Breckenridge WH, Chapman CYN and Viehland LA, J. Chem. Phys 133 164302 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ulrich B, Vredenborg A, Malakzadeh A, Schmidt L Ph. H, Havermeier T, Meckel M, Cole K, Smolarski M, Chang Z, Jahnke T and Dörner R, J. Phys. Chem. A 115 6936 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Aziz RA and Slaman MJ, Chem. Phys 130 187 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wuest A and Merkt F, J. Chem. Phys 118 8807 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang X, Dagdigian PJ, and Alexander MH, Chem. Chem. Phys 1083522 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gdanitz RJ, Chem. Phys. Lett 348 67 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lei J and Dagdigian PJ, Chem. Phys. Lett 304 317 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zh Fu., Lemire GW, Bishea GA, and Morse MD, J. Chem. Phys 93 1692 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- [23].Heidecke SA, Fu Zh., Colt JR andMorse MD, J. Chem. Phys 97 1692 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- [24].Safronova MS, Mitroy J, Clark CW and Kozlov MG, AIP Conf. Proc 1642 81 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- [25].Landau LD and Lifshitz EM, Quantum Mechanics (Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jackson JD, Classical Electrodynamics (Wiley, New York, 1975) p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Reshetnikov N, Curtis LJ, Brown MS and Irving RE, Phys. Scr 77 015301 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mitroy J, Safronova MS and Clark CW, Arxiv (2010) 1004.3567. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Friedberg R and Yu Y-K, Phys. Rev. B 46 6582 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Doerr TP and Yu Y-K, Am. J. Phys 82460 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kaplan IG, Intermolecular Interactions: Physical Picture, Computational Methods and Model Potentials (John Wiley & Sons, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- [32].Casimir HBG and Polder D, Phys. Rev 73 360 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA Jr., Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith T, Kobayashi R., Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, and Fox DJ, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gaiser C and Fellmuth B, Eur. Phys. Lett 90 63002 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dunning TH, J. Chem. Phys 90 1007 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- [36].It can be found by considering the interaction energy of a point charge and a dielectric sphere. The multipole polarizabilities are defined as the inverse of the coefficients in the sum of squares of individual multipole moments.

- [37].We note that in the relativistic case, there exists an important length scale λ = hc/ΔE, with h being Planck’s constant, c the speed of light, and ΔE the energy difference between the excited atomic states and the ground state. When L ≪ λ, the dipole–dipole interaction can be viewed as instantaneous and described non-relativistically. When L ≫ λ, the retardation effect, as shown by Casimir and Polder [31, 32], weakens the interaction strength by a factor ~ 1/L, changing the London energy from being proportional to 1/L6 to being proportional to 1/L7. Generally, λ is at least 102 to 103Å and is much larger than the distance under consideration in this manuscript. Hence, we employ non-relativistic formalisms here.

- [38].To obtain a relatively accurate value of 2.64 for the static dipole polarizability of Ne (cf. the experimental value of 2.66 [34], where a0 is the Bohr radius) requires computations at the coupled clusters, CCSD(T), or MP4 levels of theory with large basis sets such as augmented correlation-consistent quintuple-zeta basis set, aug-cc-pV5Z, of Dunning [35]. Exclusion of the diffuse functions (cc-pV5Z basis set) immediately brings down the value of polarizability to 1.85 . Consequently, the interaction energy is also severely underestimated. With the same basis, aug-cc-pV5Z, the B3LYP functional, a staple of density functional theory, overestimates the polarizability by 6% . The B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) combination, frequently used in quantum chemistry, gives only 1.23 underestimating the induced dipole-monopole interaction by a factor of 2.

- [39].Note that the well only exists in the polarization part of the interaction energy: due to the Coulomb repulsion there is no bound state for two Al+ ions.

- [40].We added definitions of aluminum ions into the set of predefined atom types of the AMOEBA polarizable force field [11] within TINKER 7.1 with the value of polarizability calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ level.