Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorders (SUD) are complex psychiatric conditions that commonly co-occur. No preferred, evidence-based treatments for PTSD/SUD comorbidity are presently available. Promising integrated treatments have combined prolonged exposure therapy with cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention therapy for SUD. We describe a case study that showcases a novel, integrated cognitive-behavioral treatment approach for PTSD/SUD, entitled Treatment of Integrated Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use (TIPSS). The TIPSS program integrates cognitive processing therapy with cognitive-behavioral therapy for SUD for the treatment of co-occurring PTSD/SUD. The present case report, based upon a woman with PTSD comorbid with both cocaine and alcohol dependence, demonstrates that TIPSS has the potential to effectively reduce PTSD symptoms as well as substance use.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder, integrated treatment, cognitive processing therapy, case study

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorders (SUD) are complex psychiatric conditions that commonly co-occur (e.g., Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005 McCauley, Killeen, Gros, Brady, & Back, 2012; Pietrzak, Goldstein, Southwick, & Grant, 2011), presenting an immense challenge to clinical practitioners. The comorbidity is complex, difficult to treat, and marked by a more costly and chronic clinical course, when compared to either disorder alone (e.g., McCauley, et al., 2012; Mills, Teesson, Ross, & Peters, 2006; Schafer & Najavits, 2007). However, the majority of treatment-seeking patients with PTSD/SUD only receive SUD treatment (Najavits, Sullivan, Schmitz, Weiss, & Lee, 2004; Young, Rosen, & Finney, 2005), contrary to most patients’ preferences (Back, Brady, Jaanimagi, & Jackson, 2006; Brown, Stout, & Gannon-Rowley, 1998).

To date, there is no consensus regarding “best practice guidelines” for this comorbidity, and most treatment-seeking individuals with PTSD/SUD are transferred between PTSD and SUD treatment services with little care coordination (Roberts, Roberts, Jones, & Bisson, 2015; Torchalla, Nosen, Rostam, & Allen, 2012; van Dam, Vedel, Ehring, & Emmelkamp, 2012). Based on recent meta-analytic evidence and critical reviews of the literature, there is promise in the preliminary efficacy of individualized integrated trauma-focused therapy plus evidence-based SUD interventions (Roberts, et al., 2015; Simpson, Lehavot, & Petrakis, 2017). Most such programs have combined prolonged exposure therapy (PE; Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007), one of the gold-standard evidence-based therapies for PTSD (Forbes et al., 2010; Powers, Halpern, Ferenschak, Gillihan, & Foa, 2010), with cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention therapy for SUD (Carroll, 1998; Marlatt & Donovan, 2007). For example, Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and SUD with Prolonged Exposure (COPE; Back et al., 2014; Mills et al., 2012) is a 12-session (90 minutes each), individually delivered integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD/SUD. The PE component provides in-vivo and imaginal trauma exposures. In-vivo exposures are designed to help individuals safely and repeatedly approach trauma-related external reminders, while imaginal exposures facilitate repeated revisiting of traumatic memories so as to decrease emotional reactivity and gain new insights. The SUD component is based upon cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention principles (Carroll, 1998; Dutra et al., 2008; Irvin, Bowers, Dunn, & Wang, 1999; Marlatt & Donovan, 2007; McHugh, Hearon, & Otto, 2010) and designed to help individuals identify external (i.e., high-risk situations) and internal (i.e., cognitive, emotional) triggers for substance use and to adaptively manage craving through various techniques (e.g., cognitive restructuring, stimulus control). The COPE program is one of the most promising treatments for PTSD/SUD available, and since it is still at a relatively early stage of development, COPE will benefit from continued evaluation across populations. Recent meta-analyses and reviews suggest that, taken together, available PTSD/SUD treatments—regardless of treatment type—are marked by small effect sizes and high rates of attrition (e.g., Coffey et al., 2016; Foa et al., 2013; Miles, Smith, Maieritsch, & Ahearn, 2015; Mills et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2015; Szafranski, Gros, Menefee, Wanner, & Norton, 2014). These findings underscore the challenging clinical nature of the PTSD/SUD population, thus highlighting the need to evaluate and refine extant interventions and to develop novel, evidence-based treatment programming for this comorbid population.

No studies to date have developed a PTSD/SUD treatment based upon the integration of cognitive processing therapy (CPT; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2008; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002; Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993), another gold-standard treatment for PTSD (Forbes et al., 2010), with cognitive-behavioral therapy for SUD for the treatment of PTSD/SUD (Carroll, 1998; Marlatt & Donovan, 2007). CPT is based upon a social-cognitive theory of trauma (Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993), which emphasizes the interpretation of the traumatic event and coping in its aftermath. Social-cognitive theories focus on the content of cognitions and the impact of thoughts on emotions and behavior; emotional expression is needed to alter the emotional elements of trauma memories and not for purposes of habituation (Resick & Schnicke, 1993). Thus, CPT is designed to target trauma-related cognitions (Galovski et al., 2016; Resick et al., 2008), particularly those relevant to five central themes: safety, power/control, intimacy, trust, esteem, in order to facilitate cognitive-emotional processing of the trauma and thus alleviate PTSD symptomatology. Techniques such as Socratic questioning are utilized throughout treatment to target trauma-related cognitions and create more balanced views of the self, others, and the world in the aftermath of trauma. Unlike PE, CPT does not include in-vivo or imaginal exposures, although the traditional form of CPT includes written “trauma narratives,” which ask individuals to write about the trauma in vivid detail. CPT is as effective as PE for the treatment of PTSD (Resick et al., 2002) and may be more effective at targeting trauma-relevant emotions such as guilt (Resick et al., 2002). In addition, preliminary studies indicate that CPT for the treatment of PTSD is well-tolerated by individuals with co-occurring PTSD and alcohol use disorder (Kaysen et al., 2014; McCarthy & Petrakis, 2011), as compared to those with PTSD-only, and leads to significant reductions in PTSD symptomatology regardless of alcohol use disorder diagnosis (Kaysen et al., 2014).

Thus, a novel integrated cognitive-behavioral treatment was developed, the Treatment of Integrated Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use (TIPSS). The TIPSS is comprised of 12, individual, 60-minute sessions that integrate CPT for PTSD with cognitive behavioral relapse prevention for SUD. The CPT treatment components are designed to target trauma-related cognitions (Galovski et al., 2016; Resick, Galovski, et al., 2008) in order to facilitate cognitive-emotional processing of the trauma and thus alleviate PTSD symptomatology. The SUD treatment components are based upon cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention principles that are intended to facilitate awareness and management of cravings, review coping skills for high-risk substance-related cognitions and situations, and provide a greater understanding of the associations between thoughts, feelings, and substance use behaviors and cravings via functional analyses (Carroll, 1998; Marlatt & Donovan, 2007). The purpose of the present article is to depict this new treatment approach via a case study presentation, drawn from the context of a randomized controlled trial (NCT02461732; Vujanovic, Smith, Green, Lane, & Schmitz, 2018).

Method

Participant

Many of the participant’s personal characteristics were altered to protect confidentiality. The participant was a 53-year-old, divorced, black/African American woman. The participant presented to treatment with severe PTSD per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th Edition (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) as well as current (past month) cocaine dependence and current (past month) alcohol dependence per DSM-IV (APA, 2000). Additionally, the participant met criteria for current Panic Disorder without Agoraphobia and recurrent Major Depressive Disorder, although these disorders were not the targets of treatment.

Trauma History

The participant reported an extensive trauma history comprised of 12 traumatic life events, including sexual assault, being held in captivity, and several physical assaults, including chronic physical abuse in the context of a violent domestic partnership. The participant reported her index trauma, or the most disturbing/distressing traumatic event, as a sexual assault perpetrated by a male acquaintance 7 years ago. The participant reported that she was raped, threatened with a knife, and then held captive in the perpetrator’s apartment for 2 subsequent days. After escaping from the apartment, the participant was treated for severe injuries and hospitalized for 1 week.

Substance Use History

The participant reported a 10-year history of regular crack cocaine use, which started during a physically and sexually abusive relationship with her now ex-husband. She also reported a long-standing history of regular alcohol use, starting during adolescence. The participant reported that she has attended over 20 drug treatments, including inpatient and outpatient programs as well as self-help (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous) meetings. She reported a history of marginal SUD treatment success, as she was able to stay clean and sober for several months after completing a residential substance use treatment program. Her longest period of sobriety was 5 years.

Medical and Psychiatric History

The participant reported four prior medical hospitalizations: two as a result of being physically assaulted and two as a result of severe physical abuse by her former husband. The participant reported that she suffers from osteoarthritis and no other medical conditions. She reported a significant psychiatric history with several prior outpatient treatments for depression and PTSD, as well as three inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, the last of which was 10 years ago. She stated that she was currently not taking any medications.

Psychosocial History

At the time of treatment, the participant was divorced from her former husband, who had abused her physically and sexually throughout their 10-year marriage. She resided with her boyfriend and daughter at the time of treatment and reported chronic conflict with her current boyfriend due to her substance use. The participant also reported an adult daughter from whom she was estranged. With regard to education, she completed college approximately 30 years ago. She was employed full-time until 1 year prior to treatment, when she was dismissed due to functional impairment resulting from chronic crack cocaine use. She stated that she relied on financial support from family and friends in order to support her living expenses and substance use.

Legal History

The participant reported three previous driving under the influence (DUI) arrests and two public intoxication charges. At the time of treatment, she was not experiencing any legal problems but expressed concern about future legal problems given her chronic, daily use of cocaine.

Procedure

The participant’s progress was objectively monitored via standardized assessment throughout treatment, using the measures and assessment schedule summarized below. Her assessments were administered by staff other than her therapist to ensure standardization and objectivity.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Diagnoses (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996)

The SCID-I is a well-established structured diagnostic interview designed to assess major DSM-IV Axis I disorders. The DSM-5 version of the SCID was not yet available at the onset of the study. The SCID-I was administered at baseline.

Addiction Severity Index-Lite (ASI-Lite; Cacciola, Alterman, McLellan, Lin, & Lynch, 2007; McLellan et al., 1992)

The ASI-Lite is a well-established, multidimensional, interview-based measure for SUD that assesses seven domains: alcohol and drug use, medical and psychiatric health, employment/self-support, family-social relations, and illegal activity. Items across each of the seven domains assess current (i.e, past 30 days) and lifetime status and functioning. The ASI-Lite was administered at baseline (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Addiction Severity Index at Baseline

| Baseline | |

|---|---|

| Cocaine | |

| Past Month Cocaine Use Days | 15 |

| Total Cocaine Use Years | 10 |

| Cocaine Administration Route | Smoking |

| Money Spent on Cocaine | $1,000.00 |

| Past Month Cocaine Problem Days | 30 |

| Extent Cocaine Use is Bothersome | Extremely |

| Cocaine Treatment Importance | Extremely |

| Alcohol | |

| Past Month Alcohol Use Days | 7 |

| Total Alcohol Use Years | 35 |

| Past Month Alcohol Intoxication Days | 7 |

| Total Alcohol Intoxication Years | 35 |

| Money Spent on Alcohol | $50.00 |

| Past Month Alcohol Problem Days | 30 |

| Extent Alcohol Use is Bothersome | Extremely |

| Alcohol Treatment Importance | Extremely |

Note. Item responses concerning past month time-frames are out of 30 days.

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., 2013)

The CAPS-5 is a well-established, 30-item structured interview for the assessment of PTSD diagnosis and severity. The 20 DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, each rated on a 5-point Likert-style scale (0 = absent to 4 = extreme/incapacitating), are assessed with regard to frequency and intensity; duration of symptoms, subjective distress, and relevant impairments in functioning are also determined. CAPS-5 ratings range from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. A past-month time-frame was used. The CAPS-5 was administered at baseline and at the end of treatment (Session 12).

PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version-5 (PCL-5; Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure of PTSD symptom severity. Each of the 20 items reflects a DSM-5 symptom of PTSD (APA, 2013), and each item is rated on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all to 4 = Extremely) in terms of how often an individual has been bothered by the symptom in the past month. Total symptom severity scores range from 0–80, where higher scores indicate higher symptom severity. A preliminary PTSD cut-off score of 33 is recommended in the current literature (Bovin et al., 2016). The PCL-5 was administered at baseline and at the beginning of each of the 12 treatment sessions.

Time-Line Follow-back (TLFB; Robinson, Sobell, Sobell, & Leo, 2014; Sobell & Sobell, 1992)

Self-report of all substance use was collected using the TLFB procedure to gather information about the timing, number of episodes, and amount of substance used. The TLFB was administered at baseline and at the beginning of each of the 12 treatment sessions.

Alcohol Breath Sample

Breath samples were used to estimate blood alcohol content (BAC) at the time of each visit. The Alco-Sensor III was used to assess BAC. Levels over.00 required a meeting with the nurse practitioner for an intoxication assessment. Breath samples were collected at baseline and at the beginning of each of the 12 treatment sessions.

Urine Drug Screening (UDS)

UDS was used as an objective index of presence vs. absence of substance use. The integrated E-Z split key cup II (Innovacon Company, San Diego, CA) was used to test for urine cocaine (benzoylecgonine), tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), opiates, amphetamine, and benzodiazepines. Urine samples were collected at baseline and at the beginning of each of the 12 treatment sessions.

Therapist Training and Protocol Fidelity

The therapist who administered the TIPSS for the present case was a licensed M.A.-level professional counselor, with 6 years of post-degree experience in treatment of SUD. She completed an online CPT training course and extensive training on the TIPSS manual with the study PI. The therapist had administered TIPSS to five participants prior to the present case. The therapist met with the study PI for weekly group supervision meetings. All study sessions with the participant were audio-recorded as part of the research protocol. The PI confirmed, via audio review of all sessions, that the current participant received the standardized TIPSS protocol.

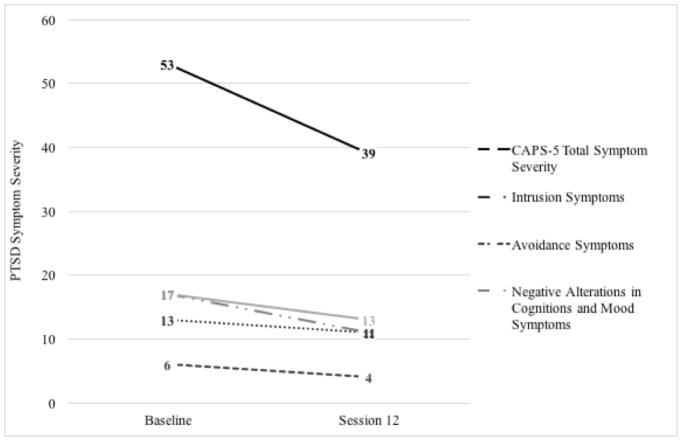

Treatment

The TIPSS is a novel cognitive-behavioral therapeutic approach designed for the treatment of co-occurring posttraumatic stress and SUD (Vujanovic, 2014). The TIPSS combines cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for SUD (Carroll, 1998; Marlatt & Donovan, 2007) with CPT for PTSD (Resick, Monson, et al., 2008; Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993), and many of the exercises employed in TIPSS are derived from CPT (Resick, Monson, et al., 2008; Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993). The treatment program includes 12 sixty-minute sessions of individual psychotherapy administered twice weekly over 6 weeks. The participant’s progress is included in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

PTSD and Substance Use Outcomes Throughout TIPSS Intervention

| PCL-5 | CAPS-5 | TLFB (Cocaine) | TLFB (Alcohol) | Money Spent (Cocaine) | Alcohol Breathalyzer | UDS (Cocaine) | UDS (Other) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 59 | 53 | 6/9 days (67%) | 5/9 days (56%) | $480 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 1 | 60 | — | 5/9 days (56%) | 6/9 days (67%) | $450 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 2 | 59 | — | 2/5 days (40%) | 2/5 days (40%) | $250 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 3 | 67 | — | 1/2 days (50%) | 1/2 days (50%) | $80 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 4 | 63 | — | 3/7 days (43%) | 3/7 days (43%) | $430 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 5 | 56 | — | 2/2 days (100%) | 1/2 days (50%) | $110 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 6 | 60 | — | 3/5 days (60%) | 1/5 days (20%) | $210 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 7 | 59 | — | 0/2 days (0%) | 0/2 days (0%) | $0 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 8 | 59 | — | 3/5 days (60%) | 4/5 days (80%) | $330 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 9 | 41 | — | 0/2 days (0%) | 0/2 days (0%) | $0 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 10 | 53 | — | 2/4 days (50%) | 1/4 days (25%) | $190 | 0 BAC | Positive | Negative |

| Session 11 | 37 | — | 0/7 days (0%) | 2/7 days (29%) | $0 | 0 BAC | Negative | Negative |

| Session 12 | 40 | 39 | 0/1 days (0%) | 1/1 days (100%) | $0 | 0 BAC | Negative | Negative |

Note. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 total score; CAPS-5 = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 total score; TLFB = Time Line Follow Back; % indicates percent of days between sessions that the participant reports to have used cocaine or alcohol (as indicated), per TLFB self-report; Money Spent (Cocaine) = past week money spent on cocaine; 0 BAC = negative breathalyzer (alcohol); UDS Cocaine = urinary drug screening positive or negative for cocaine (as indicated); UDS Other = urinary drug screening positive or negative for amphetamines, benzodiazepines, methamphetamines, opiates, and cannabis (as indicated).

FIGURE 1.

Trauma outcomes throughout TIPSS intervention. The CAPS-5 possible total score range = 0–80; possible Cluster B score range = 0–20; possible Cluster C score range = 0–8; possible Cluster D score range = 0–28; possible Cluster D score range = 0 – 24. CAPS-5 = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (14-point decrease between baseline and session 12); Cluster B = CAPS-5 intrusion (2-point decrease between baseline and session 12); Cluster C = CAPS-5 avoidance (2-point decrease between baseline and session 12); Cluster D = negative alterations in cognitions and mood (6-point decrease between baseline and session 12); Cluster E = arousal (4-point decrease between baseline and session 12).

Each session begins with a review of the participant’s reported substance use (TLFB and UDS results), cravings, and PTSD symptoms since the last session. Instances of substance use are debriefed with identification of any trauma-related or other pertinent triggers; and functional analyses are conducted to help the participant better understand the antecedents and consequences of substance use. Relevant coping skills to employ in instances of future cravings are also discussed. Next, “home therapy” related to the previous session topic (e.g., beliefs about the cause and impact of the trauma, records of coping, detailed written trauma account, changing problem thinking and challenging beliefs) is reviewed and the topic for the current session is presented. To reduce reinforcement of avoidance, therapists encourage participants to complete any missed home therapy assignments at the beginning of the session (see Table 3 for an outline of each session).

Table 3.

Session Outline for TIPSS

| Session Title | Session Goal | Session Activity | Homework | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Introduction and Overview | Rapport Building and Treatment Description | Treatment overview and expectations. Motivational Interviewing |

Write about the role of substance use in their lives when they first started and now. |

| Session 2 | Education, History, & Triggers | Psychoeducation on PTSD/SUD. | Psychoeducation on use and maintenance model of PTSD. Discuss substance use triggers. | Valued Living Questionnaire |

| Session 3 | Values | Identify values related to recovery from PTSD and SUD. | Valued Action Worksheet and psychoeducation on coping skills. | Self- monitoring coping of trauma cues and cravings. |

| Session 4 | Coping Skills | Learn new coping skills for handling cravings and trauma- related stress. | Deep breathing, mental grounding, guided imagery, and mindfulness. | Impact statements on trauma and substance use. |

| Session 5 | Impact of Trauma and Substance Use | Psychoeducation on relatedness of thoughts and feelings. | ABC model is taught. | ABC worksheets |

| Session 6 | Identification of Thoughts and Feelings | Participant identification of relatedness between their thoughts and feelings. | Review ABC worksheets and use of Socratic questioning to identify alternatives. | Written trauma narrative |

| Session 7 | Remembering the Trauma | Identify thoughts and feelings related to trauma. | Read trauma narrative aloud and discussion of related thoughts and feelings. | Re-write trauma narrative to include more detail and read narrative daily. |

| Session 8 | Remembering the Trauma II | Emotional and cognitive processing of the trauma | Emotional processing and Socratic questioning related to stuck points. | Challenging Beliefs Worksheet |

| Session 9 | Problem Thinking | Analyze and confront stuck points related to PTSD and SUD. | Additional Challenging Questions Worksheets and Problematic Thinking Patterns Worksheet are completed and discussed. | Problematic Thinking Patterns Worksheet |

| Session 10 | Themes: Trust and Safety | Relate PTSD and substance use behavior to themes of trust and safety. | Discussion of themes using Socratic questioning. | Challenging Beliefs Worksheets to identify stuck points related to the specified themes. |

| Session 11 | Themes: Power, Control, and Intimacy | Relate PTSD and substance use behavior to themes of power, control, and intimacy. | Discussion of themes using Socratic questioning. | Challenging Beliefs Worksheets to identify stuck points related to the specified themes. |

| Session 12 | Graduation and Wrap-up | Review treatment and prepare for consolidation. | Discuss PCL-5 scores, elicit feedback, and motivate to engage. | N/A |

Note. TIPSS is composed of a synthesis of content derived from cognitive processing therapy (Resick & Schnick, 1992) and cognitive-behavioral therapy for SUD (McGovern, et al., 2009). Each session begins with a review of the participant’s reported substance use, cravings, and PTSD symptoms since the last session. Instances of substance use are debriefed with identification of any trauma-related or other pertinent triggers; and functional analyses are conducted to help the participant better understand the antecedents and consequences of substance use. Relevant coping skills to employ in instances of future cravings are also discussed. Valued Action Worksheet based on materials developed by Wilson and DuFrene (2012). ABC = Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Blevins, et al., 2015). Valued Living Questionnaire derived from Wilson and colleagues (2010).

Session 1 Overview

Session 1, “Introduction and Overview,” is a rapport-building session which includes a description of the treatment plan and expectations of the participant. Session 1 elicits motivation to engage in treatment using elements of Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991), including a balance scale (pros/cons of substance use; pros/cons of facing the trauma) and motivational rulers (rating importance, confidence, and readiness to make changes in substance use behaviors and PTSD symptoms). Participants are assigned a written home therapy exercise to write about the role that their substance use played when they first started using and the role that it currently plays.

Session 1 Participant Data

The participant reported that she had used substances on most days since the baseline session. Specifically, she reported using cocaine on 56% (5/9) of days and alcohol on 67% (6/9) of days since baseline. Upon arrival for Session 1, she tested positive for cocaine (UDS). The participant was engaged and appeared highly motivated to participate in treatment. She identified significant distress over her substance use with the following “cons” on her balance scale: house is a mess; job loss; lying; spending money; destroying relationships with family; feeling useless; neglecting responsibilities and bills; low self-esteem. When discussing the “pros” of her substance use, she stated, “Just for a moment, I don’t have to feel anything. I can’t explain it any other way. It’s not a happy joyous feeling, it’s just an escape. … I don’t want to feel anymore.” With regard to the motivational rulers assessing importance, readiness, and confidence in quitting cocaine, she provided ratings of 9, 7, and 3, respectively.

In terms of the pros and cons in facing the trauma, the participant stated that she was worried that the trauma work “might kill me.” She added her concern that if she examined the “truth” of her life, she would realize that she is “not lovable” because she was abused by so many people throughout her life. She worried that facing the trauma “is just too horrible. I’ll want to die.” She listed the pros of the trauma work to include using substances less and regaining a stable life. She rated her motivation to change her PTSD symptoms at 9 for importance, 2 for confidence, and 10 for readiness.

Session 2 Overview

Session 2, “Education, History, and Triggers,” begins with a discussion of the written home therapy from Session 1. The therapist probes with regard to the role trauma has played in the participant’s substance use. Additional information about PTSD and substance use is provided including statistics and illustrations showing the strong associations between PTSD symptoms and substance use; and the cyclical nature of PTSD/SUD. For example, individuals may use substances to cope with PTSD symptoms, but substance-related withdrawal symptoms might exacerbate PTSD symptoms, leading to greater substance use over time. Participant triggers for substance use (both trauma and nontrauma related) are discussed and the Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ; Wilson, Sandoz, & Kitchens, 2010) is assigned as home therapy.

Session 2 Participant Data

Since Session 1, the participant reported to have used both cocaine and alcohol on 40% (2/5) of days. She tested positive for cocaine (UDS) upon arrival to this session. The participant arrived with her completed home therapy regarding the role that substance use has played in her life. She described cocaine as “the first thing that ever lifted me up out of my depression.” She acknowledged increasing substance use when “my ex-husband started to abuse me—hit me and cheat on me and sodomize me and more. The cocaine and alcohol became the way to kill the pain.” She recognized that her continued use of cocaine over time was to “kill the underlying pain.” The participant added that crack helps her to “escape for 5 minutes at a time.” She further described, “Alcohol and crack are a means of self-medication—it’s not fun to use, it is purely an uncontrollable craving.” The participant was able to recognize and discuss associations between PTSD and substance use in her life and to identify their patterns of co-existence of time.

Session 3 Overview

Session 3, “Values,” begins with a review of the VLQ to identify the participant’s life values. Participants discuss how recovery from PTSD symptoms and substance use may be connected to their values. Participants complete the Values Action Worksheet (Wilson & DuFrene, 2012) and choose three of their most important values, write a short sentence about each, and then choose three small actions that they could complete over the week in order to move them toward their values. The session ends with a discussion of positive and negative coping skills. Participants are assigned home therapy to monitor how they cope with trauma cues and substance cravings.

Session 3 Participant Data

The participant reported using both cocaine and alcohol on half of the days since Session 2 (50%; 1/2 days), and she tested positive for cocaine (UDS). At the start of the session, the participant reported continued substance use with intensified cravings, stating that she believed therapy was bringing up emotions that were triggering more severe cravings. Functional analyses regarding her substance use were conducted to illuminate triggers and consequences of use. The participant stated she was proud of herself for being able to maintain treatment participation. Upon discussion of the Values Action Worksheet, the participant identified her values as parenting, family relationships, and work. She then stated that substance use and PTSD had been negatively impacting her engagement with these values. During the session, the participant became overwhelmed with emotion and asked to leave. She stated that she felt like she was “going to be sick and vomit.” The therapist took the participant through a grounding and breathing exercise (see descriptions below) and the participant was then able to continue and finish the session with a discussion of her positive and negative coping skills. For home therapy, the participant was asked to complete a Record of Daily Coping worksheet, which asks about daily coping activities.

Session 4 Overview

Session 4, “Coping Skills,” begins with a review of the participant’s committed action goals as well as reported coping since the last session. In-session training involves the therapist demonstrating and the participant practicing new coping skills for handling cravings and trauma-related distress, including deep breathing and grounding exercises (e.g., Linehan, 1993a, 1993b, 2014). Grounding involves occupying the mind with neutral things (e.g., names of cities) or objects in the person’s present space; bringing awareness to present-moment physical sensations (e.g., noticing temperature or texture of objects or surfaces); and/or imagining the mind filling up with a favorite color or visualizing being at a peaceful location, such as a beach. A mindfulness technique, “urge surfing” (Marlatt, 1994; Ostafin & Marlatt, 2008), that creates awareness and curiosity of the internal experiences during a craving, is introduced and reviewed to help participants “ride out the wave” of cravings without trying to change their internal experiences.

Session 4 Participant Data

The participant reported using both cocaine and alcohol on 43% (3/7) of days since Session 3 and tested positive for cocaine (UDS) upon arrival. Although the overall number of days of using both cocaine and alcohol reduced, she started the session by reporting a 2-day heavy binge of cocaine use, which she attributed to escalating relationship problems with her boyfriend as well as continued trauma triggers. The participant completed her coping record and reported some short-term relief from cravings when using positive coping skills, such as reading and praying. Overall, the participant reported feelings of hopelessness surrounding her addiction but continued willingness to pursue treatment. Within the following excerpt, the therapist explored some of the maladaptive thoughts surrounding the participant’s substance use.

THERAPIST: What would happen in those moments when you were craving cocaine so badly and you didn’t get it?

PARTICIPANT: I would probably explode and die.

THERAPIST: Have you ever had times in your inpatient programs when you wanted cocaine but you couldn’t use?

PARTICIPANT: Yes

THERAPIST: What happened?

PARTICIPANT: I usually went to sleep.

The participant reacted favorably to the coping skills, with a preference for mental grounding and soothing grounding. For home therapy, two impact statements were assigned. The participant was asked to write two pages (one page for trauma; one page for substance use) on how the traumatic event or her substance use has affected her beliefs about herself, others, and the world as related to themes of safety, trust, power/control, esteem, and intimacy.

Session 5 Overview

Session 5, “Impact of Trauma and Substance Use,” begins with the participant reading both trauma and substance use impact statements aloud to the therapist. The therapist listens for stuck points (i.e., problem-areas in thinking that interfere with the recovery process and keep the patient “stuck”) and problematic thoughts/beliefs and gently points out examples of beliefs interfering with acceptance of the event (assimilation) and any extreme, overgeneralized beliefs (overaccommodation). The A-B-C model (Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence) of how beliefs influence emotions and behavior is presented with a discussion about the relatedness of thoughts and feelings. Participants are assigned ABC worksheets to assist in the identification of their thoughts and feelings related to both trauma- related thoughts/triggers and substance-related thoughts/triggers.

Session 5 Participant Data

Upon arrival, the participant disclosed that she had used alcohol on half the days since the last session (50%; 1/2 days). She tested positive for cocaine (UDS) and reported that her continued use of cocaine (100%; 2/2 days) since Session 4 was exacerbated by her fear of being home alone as her boyfriend had left the house. She reported that she was now having significant trouble sleeping, waking every 15 minutes in fear, thinking that “something bad was going to happen” and that she would be unable to protect herself. The antecedents and consequences of use were explored. The participant had not completed her impact statement, but reported that she had started working on the assignment. The therapist asked the participant to discuss the part of the impact statement that she had completed and asked her to complete the remainder for the next session. The following excerpt demonstrates how the therapist began to use Socratic questioning with regard to one of the participant’s stuck points, “I should have prevented it.”

PARTICIPANT: It happened because it’s my fault. If I wouldn’t be choosing the wrong people to be around, if I would have seen the red flags, I would have seen the signs of him starting to slip off into some madness, and then I could have prevented it.

THERAPIST: If you had just looked closer, you would have known.

PARTICIPANT: If I wouldn’t have let the need for the drug overshadow what I was seeing, the little signs of danger.

The therapist then explained hindsight bias (i.e., the tendency to view events as more predictable than they actually were, after the event occurred). The participant began to cry and stated she was experiencing intrusive memories of the rape. She reported having “yucky feelings,” and then continued.

PARTICIPANT: If I would have seen some of the signs, because there was another girl there and they were using me, they were putting me down, just all the memories are coming up. [crying]

THERAPIST: If you could put yourself back at the time then, not what you know now, but what you knew then, were you saying to yourself that day, “I think he’s going to rape me?”

PARTICIPANT: No… no… not at all.

THERAPIST: If you had said that to yourself, like if you had known back then that if I go into this room, I’m going to be raped, would you have gone in the room?

PARTICIPANT: [crying] No, no way, no way…. I didn’t have to use there.

Session 6 Overview

Session 6, “Identification of Thoughts and Feelings,” begins by reviewing the A-B-C sheets related to trauma and substance use. The therapist helps the participant label and understand thoughts as thoughts and feelings as feelings. Each A-B-C sheet is reviewed with attention to the idea that noticing and/or changing thoughts can influence the intensity and type of emotion(s) experienced. Once participants appear to have an adequate understanding of the general concepts, therapists use Socratic questioning to help participants generate alternatives to problematic thoughts recorded on the A-B-C sheets. Participants are assigned the written trauma narrative to complete before the next session. Participants are instructed, “Write a full account of the traumatic event and include as many details as possible. Write it as if it were happening right now. Details should include: sights, sounds, smells, etc. Also include as many thoughts and feelings that you remember experiencing during the event.” Writing while intoxicated or high is discouraged and the use of coping skills learned in session four is encouraged. Participants are instructed to read the trauma narrative daily and allow themselves to feel their feelings.

Session 6 Participant Data

Upon arrival to Session 6, the participant reported cocaine use on 60% (3/5) of days and alcohol use on 20% (1/5) of days since the last session. She also tested positive for cocaine (UDS) upon arrival. During the session, standard cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention principles were employed (e.g., functional analyses, identification of triggers). The participant had completed her written impact statements and several patterns of problematic thinking were identified, including: oversimplifying, exaggerating, emotional reasoning, and disregarding important aspects of a situation. Common cognitive distortions were noted; for example, personalizing and regret orientation (e.g., “If I hadn’t been using, I wouldn’t have been raped”; “It was my fault”; “I got what I deserved”); overgeneralizing (e.g., “Men are dangerous, violent creatures who hate women”; “The world is not safe”); catastrophizing (e.g., “I am an addict who has lost the power to choose”); and discounting positives (e.g., “There’s something wrong with me because I haven’t been able to quit using cocaine”). She also completed her A-B-C worksheets with a demonstrated understanding of the connection between thoughts and feelings, but limited ability to consider alternative ways of thinking.

The participant was presented with the home therapy exercise to write about the traumatic experience in detail. She became very distressed when thinking about writing it and stated, “I might die” and “I’ll go insane and never recover,” as well as expressing concerns about her safety and disappointing the therapist. Within the following excerpt, the therapist and the participant discussed these concerns.

THERAPIST: What fears, thoughts do you have right now about this exercise?

PARTICIPANT: Pretty bad, I don’t know if I can do it. It just scares me, getting to that level of horror.

THERAPIST: So, if you experience the horror …

PARTICIPANT: I might just … die. I don’t know. I’ll have to think about it.

THERAPIST: It’s really common for people to think that way, that this will just put them over the edge. Even if you absolutely think that way, I believe you will be okay. I actually had a participant say, “If I feel this, I will throw the chair across the room.” And you know what? He didn’t.

PARTICIPANT: Just thinking of letting them [the emotions] out is terrifying me.

THERAPIST: That’s a very very common belief. That’s normal.

PARTICIPANT: I just can’t tell you one way or another if I am ready for it right now or not.

THERAPIST: That’s okay. It’s up for you to decide.

PARTICIPANT: I’m angry all of a sudden.

THERAPIST: Can you go underneath that anger?

PARTICIPANT: No, not right now.

THERAPIST: Part of that anger might be directed at me for asking you to do something that you don’t want to do, and people having told you to do things you don’t want to do your whole life.

PARTICIPANT: Yeah, it’s like you don’t even know if this might kill me, and you’re still asking me to do it. And I don’t want to disappoint you, but I just don’t know if I can do it.

THERAPIST: Let’s talk about that. Number one, if you don’t think you can do it, it doesn’t mean that you cannot. If you decide not to do it, I’m not going to be disappointed at all. Not in the slightest. The most important thing is that you just come back. I’ll be disappointed if you don’t come back.

PARTICIPANT: Oh, I’ll come back. I just don’t know right now. Let me give it some thought.

THERAPIST: Absolutely. I want you to take time for some serious thought. Emotions themselves cannot hurt you, but when you think that you cannot handle the emotions, that’s when the harm comes in.

PARTICIPANT: Right, that’s what it is. I’m afraid I’ll go insane … and not come back. I’ll lose my sanity and it won’t come back to me.

THERAPIST: I get that a lot in here. That’s actually the number one thought: “If I allow myself to think about it or feel it, I will go insane.” That’s the number one thought. And so far, nobody has ever done that. I cannot think of any cases in which people have gone insane and not come back. Now, you might throw up. You might feel drained for days. You might cry on and off for days. There’s a lot to process.

PARTICIPANT: Right, cumulative.

Following this dialogue, the therapist and participant continued to discuss the advantages and disadvantages to completing the exercise, and the participant agreed to give her best effort to completing the exercise.

Session 7 Overview

Session 7, “Remembering the Trauma,” begins with the participant reading the trauma narrative aloud to the therapist. Emotional expression is encouraged and the therapist refrains from interrupting the participant. Once the narrative is read aloud, the therapist leads a reflection on it to elicit the thoughts and feelings connected to the trauma. The therapist encourages discussion of how the participant coped with feelings or memories and whether substance use played a role in managing emotion. If the participant reads the account without any emotion, a discussion begins on whether the participant is holding back and why. Catastrophic beliefs related to fearing the loss of control or feeling overwhelmed by emotion are common and the therapist uses Socratic questioning to help challenge these beliefs. The therapist listens for and defines “stuck points” for the participant, as conflicts between old beliefs and the reality of the event, or negative beliefs that seemed to be confirmed by the event which lead to negative feelings like self-blame, guilt, and anger at self and others. The therapist may elicit stuck points that are not in the trauma account by asking questions such as, “Is there anything that you think you should have done differently?” Participants are assigned home therapy of rewriting the trauma account a second time with even more detail in the narrative. Participants are instructed to read the narrative to themselves daily.

Session 7 Participant Data

The participant tested positive for cocaine (UDS) upon arrival, but denied using substances (cocaine or alcohol) since the last session (0%; 0/2 days). She brought in a partially completed written trauma account to the session, reporting that she stopped writing at the point that it made her feel “sick,” which was right before she started writing about the rape. The therapist asked the participant to read what she had written and began to identify stuck points. The participant labeled herself a “fool” and blamed the rape on her decision to share her drugs with the perpetrator. She stated, “We had been up for two days using because I had some money come in, and like a fool, I shared with him almost half of what I’d bought.” Through Socratic questioning, the participant was able to realize the reasons behind why she shared her drugs (e.g., her giving nature, the loneliness she was feeling at the time, as well as a protective strategy to share drugs to prevent others from attacking her or stealing). As demonstrated by the dialogue below, she also began to explore the reasons why she did not report the perpetrator to the police at the time. For example, she had thought that the police would not have believed her and she worried that the perpetrator or his family would have hurt or killed her.

PARTICIPANT: People are mean. People think, you were using drugs, you were asking for it.

THERAPIST: You’re right, that’s a very common belief that our society has. Have there ever been times in the world where society had a belief and then we later realized that that belief wasn’t right?

PARTICIPANT: Yeah, I think we are realizing that, but it’s still there. Even my family thinks that.

THERAPIST: Yeah, I believe you.

PARTICIPANT: They’ve never even cared that I was raped. They don’t care. And these are educated people that are supposed to love me. They don’t care…And it hurts so bad. It hurts so bad. It hurts so bad that nobody cared. The people that I loved the most didn’t care about me. They just thought it goes with the territory, that’s what they said.

THERAPIST: Because rape doesn’t happen to people who aren’t drug users?

PARTICIPANT: Right [laughing through tears] …

THERAPIST: Rape doesn’t happen to children, or men, or people in the military, or women coming out of the grocery store, or babies? And you’re right. There are people who think that way, and it’s so painful.

PARTICIPANT: And they just happen to be in my family.

THERAPIST: Right, and it hurts when it’s the people you want to have your back.

PARTICIPANT: No one’s ever had my back. That’s the problem in my life.

THERAPIST: We’re going to hash this for a long time in here, this discussion that we’re having. We’re going to be having it a lot. First of all, this way of thinking has been perpetuating for the past seven years, and even before that, since you experienced multiple traumas before that. This rape just reinforced the beliefs that you already had, so getting these out in the open and really looking at them is what will help us move forward.

Following this conversation, the participant was instructed to complete the written trauma account for the next session.

Session 8 Overview

Session 8, “Remembering the Trauma II,” is a continuation of the previous session’s emotional and cognitive processing of the trauma. Participants begin by reading their rewritten, more detailed trauma account aloud to the therapist. Any differences (e.g., amount of detail, emotional expression, assimilation) between the first and second trauma narratives are discussed. The session proceeds in a similar fashion to the previous session, with additional emotional processing and Socratic questioning related to stuck points. The Challenging Beliefs Worksheet (Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993), a series of 10 questions to aid the participant in evaluating the accuracy of their beliefs, is introduced using examples drawn from the trauma narrative discussion. For example, the belief, “I was assaulted because I was high,” would be challenged by answering a series of questions such as, “Is your belief a habit or based on facts? Are you thinking in all-or-none (extreme) terms? Are you taking the situation out of context and only focusing on one aspect of the event?” The therapist helps the participant work through several examples. For home therapy, participants are asked to complete the challenging beliefs worksheet using a trauma-related stuck point and a substance-related stuck point.

Session 8 Participant Data

Since Session 7, the participant had used substances on most days, reporting cocaine use on 60% (3/5) of days and alcohol use on 80% (4/5) of days. She also tested positive for cocaine (UDS). The participant did not complete her written trauma account. In order to not reinforce avoidance, the therapist asked the participant to read aloud what she had written and then finish the remainder of the narrative by telling it aloud. Through Socratic questioning, they continued to work on stuck points such as, “It was my fault” and “I could have prevented it.” The participant began to show some greater cognitive flexibility by acknowledging that she was in a high-risk situation, but that neither the participant nor the high-risk situation caused the rape to occur, as demonstrated in the below exchange.

THERAPIST: How did you allow it to happen?

PARTICIPANT: I mean I just shouldn’t have kept using. I should have been able to stop.

THERAPIST: So only people who use drugs get raped?

PARTICIPANT: No, no that’s true. I’m sure it happens more often to those who use drugs. It happens a lot I bet. They put themselves in a bad position, and I did. I didn’t deserve it, but it’s more likely to happen. I can be honest about that…It’s more likely to happen when you’re with someone using drugs for days.

THERAPIST: So, it’s a higher risk environment maybe, like leaving your stereo in a car in a bad neighborhood.

PARTICIPANT: Right.

THERAPIST: Does that make someone take the stereo out of your car?

PARTICIPANT: No, no. I know that.

At this point in the conversation, the therapist gave an example of a recent news story of a college student drinking at a party who was then assaulted by a male attendee of the party. The continued excerpt below demonstrates the participant’s reaction to this example.

THERAPIST: Would you say it was her fault because she had been drinking?

PARTICIPANT: No. I would still stand up with her.

THERAPIST: It’s that simple. High-risk environment or not.

PARTICIPANT: Yeah. That’s true. Yeah… yeah, that’s the same thing really. It just seems less, I don’t know, like she didn’t really do anything wrong, and I did. Sometimes because it’s an illegal drug. It’s not legal what I was doing.

THERAPIST: So, jaywalking is illegal … If a woman is underage and using alcohol, that is illegal. Is that a reason to rape somebody?

PARTICIPANT: No … no. I guess it’s just the whole stigma. I know I have a disease but no one really acknowledges that. They’ll say it and see it in the medical thing but they really don’t believe it. And part of me doesn’t believe it, evidently. Even though I’ve proved it over and over.

The session continues with exploring the participant’s beliefs that are centered upon self-blame. The participant realizes that, despite the activities she was engaging in, her behavior did not cause or excuse the rape. She acknowledges that the rape was caused exclusively by the perpetrator, and that he took advantage of a situation in which she was not able to fully protect herself because she was intoxicated.

Session 9 Overview

Session 9, “Problem Thinking,” begins with a review of the Challenging Questions Worksheet. The therapist assists the participant to analyze and confront stuck points. Additional Challenging Questions Worksheets are completed within the session to address additional core trauma-related stuck points as well as substance-related stuck points that maintain substance use over time (e.g., “I’ll mess up anyway, so I might as well use”). The Problematic Thinking Patterns Worksheet (Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993), which defines seven types of problem thinking (jumping to conclusions, exaggerating or minimizing a situation, disregarding important aspects, oversimplifying, overgeneralizing, mind reading, and emotional reasoning), is introduced and reviewed. Participants are asked to notice if they have tendencies toward particular counterproductive thinking patterns. Examples generated by the participant or from prior sessions by the therapist are discussed. The therapist points out how these patterns become automatic, creating negative feelings and behaviors. Participants are assigned the Problematic Thinking Patterns Worksheet as home therapy to complete using all identified stuck points.

Session 9 Participant Data

The participant tested positive for cocaine (UDS) upon arrival but denied substance use (alcohol or cocaine) since the last session (0%; 0/2 days). She reported that she thought therapy was useful and that having someone “validate and say it wasn’t all my fault really helps.” The participant brought in her Challenging Questions Worksheets with stuck points such as, “I don’t have a chance of getting well and I should have seen the warning signs.” The therapist and participant continued to explore the context of the situation and her hindsight bias. The participant was also less emotionally labile during this and the following sessions. The participant stated that she was able to realize that the rape was not her fault, but that she had been internalizing others’ judgments and blame.

Sessions 10–11 Overview

Session 10, “Themes: Trust and Safety,” and Session 11, “Themes: Power, Control, and Intimacy,” consist of detailed discussion of the five themes, specifically how one’s beliefs about PTSD and substance use behaviors are relevant to these themes. Session 10 begins with a review of the Problematic Thinking Patterns Worksheet, and the therapist ascertains that both trauma- and substance-related thought patterns are well represented on the worksheet. Afterward, a discussion of the five themes begins. Each theme is discussed over the course of Sessions 10 and 11, starting with the participant’s prior (pretrauma and/or pre–substance use) beliefs about the theme (e.g., “Prior to the event/starting to use substances, how did you feel about your own judgement? Did you trust other people? How did your prior life experiences affect your feelings of trust?”). After determining the participant’s prior beliefs relevant to the given theme, the therapist engages the participant in a discussion of the participant’s post-trauma/substance use beliefs about the theme (e.g., “How did your beliefs about trust change from pre- to posttrauma/pre- to post–substance use? How did the trauma/substance use affect your beliefs about trust? How did substance use/involvement in drugs affect your beliefs about trust?”). The therapist helps the participant determine whether their beliefs were disrupted or reinforced by the trauma and/or substance use. A discussion regarding the theme on a continuum is broached, using Socratic questioning techniques. The goal is to help the participant consider the specified theme dimensionally versus categorically (i.e., trust vs. no trust). Participants are assigned additional Challenging Beliefs Worksheets as home therapy to be completed on identified stuck points related to the specified themes.

Session 10–11 Participant Progress

The participant reported a significant decrease in her cocaine and alcohol use during these sessions. Specifically, she reported to have used cocaine on 50% (2/4) of days and alcohol on 25% (1/4) of days at Session 10. Upon arrival to Session 11, she denied using cocaine since Session 10 (0%; 0/7 days) and reported using alcohol on 29% (2/7) of days. She tested positive for cocaine (UDS) at Session 10 and negative for cocaine (UDS) at Session 11. This was the first time that the participant had tested negative for cocaine during the entire treatment. She continued to be engaged in the treatment and completed her home exercises, showing improvement in her ability to challenge her beliefs and experience more cognitive flexibility. She also reported increased awareness of and use of coping skills to manage cravings and urges to use substances. For example, after challenging her belief that “men are untrustworthy jerks,” she was able to generate the new and more realistic belief that “only some men are untrustworthy.”

Session 12 Overview

Session 12, “Graduation and Wrap-up” begins with a review of the Challenging Beliefs Worksheets related to the five themes. Topics covered in therapy are reviewed and the therapist and participant reflect on the participant’s work throughout the 12 sessions. The therapist may share the participant’s PCL-5 score at the beginning of treatment and compare that with their score at the end of treatment. If the score changed or stayed the same, this is discussed and reasons for change (or lack thereof) are generated. Feedback is elicited from the participant regarding the treatment, his/her motivation to engage, and how the treatment might have compared to their expectations. Participants receive a certificate of completion. Referrals for additional substance abuse and mental health treatment are provided to participants along with a discussion on the participant’s future directions.

Session 12: Participant Progress

Upon arrival to Session 12, the participant reported that she used alcohol since Session 11 (100%; 1/1 days), but she reported continued abstinence from cocaine (0%; 0/1 days) and tested negative for cocaine (UDS). This represented the participant’s longest period of sustained abstinence as she had not used cocaine since before Session 10 (10 days). A review of coping skills that have worked to manage cravings and urges was conducted. During the session, she reported that she was regularly challenging her beliefs relevant to the trauma and substance use, but also about daily life activities. The participant expressed gratitude in learning skills with potential to help her not think so categorically and “harshly” about herself. She acknowledged that she would need to practice these skills daily going forward in order to not fall back into old thinking patterns.

Discussion

The present case study provides preliminary support (N = 1) for feasibility, tolerability, and initial efficacy of TIPSS for effectively targeting both PTSD and SUD symptoms concurrently in an integrated treatment model. This case study illustrated the efficacy of TIPSS in decreasing PTSD symptomatology and facilitating abstinence from substances in a woman with a history of chronic PTSD comorbid with cocaine and alcohol dependence. As delineated above, functional analysis is an important part of the TIPSS protocol and highlights the importance of addressing problematic behaviors common to both PTSD and SUD (e.g., avoidance, values-informed choices, maladaptive cognitions). For example, the participant’s maladaptive cognitions were maintaining her PTSD symptoms and her long-standing substance use. She was using substances in an effort to self-medicate (i.e., avoid) the negative emotionality and intrusive memories stemming from her trauma history, namely the rape and captivity perpetrated by an acquaintance 7 years prior. When she was able to gain greater awareness of the relations between her beliefs, emotions, and behaviors, and to challenge her trauma- and substance-related beliefs, she developed more balanced views of herself, others, and the world. This case study illustrates that it is feasible to deliver the TIPSS program in 12, one-hour individual therapy sessions. The program was well-tolerated by the participant and offered promise in terms of its effectiveness in decreasing PTSD symptoms and substance use frequency and quantity. Indeed, the participant’s regular attendance and timely completion of the treatment program as well as her positive ratings of treatment satisfaction (Table 4) are additional good indicators of the feasibility and acceptability of this treatment.

Table 4.

Participant Treatment Feedback Responses1

| Item | Response |

|---|---|

| Treatment was helpful | 10 |

| Learned about trauma/substance abuse | 10 |

| Learned coping skills | 10 |

| Better able to manage PTSD symptoms | 10 |

| Better able to manage substance use symptoms | 10 |

| Would recommend this treatment | 10 |

| Therapist helped to confront memories/feelings in a safe way | 10 |

| Therapist helped work with substance use | 10 |

| Wish treatment was longer/involved more sessions | 10 |

| I would choose to continue this treatment | 10 |

| Free response comments |

I am so grateful to be cocaine free today. I am amazed at how much this has helped me. The whole team is caring and respectful. |

Note.

Questionnaire was developed for purposes of this study. Item responses were recorded on a scale of 1 (not at all true) to 10 (absolutely true).

During the course of 12 sessions, delivered over the course of 6 weeks, this participant manifested 19-point and 14-point decreases in PTSD symptoms per the PCL-5 and CAPS-5, respectively. Notably, the participant’s progress represents “clinically significant change” in PTSD symptoms, defined as reduction of at least eight points on either DSM-5-based measure (P. P. Schnurr, personal communication, September 6, 2017). Despite these decreases, the participant continued to meet criteria for PTSD at the conclusion of treatment. Upon examining PTSD symptom cluster scores, the participant demonstrated decreases on the CAPS-5 of 2 points for the intrusion and avoidance clusters, 6 points in the negative alterations in cognitions and mood cluster, and 4 points in the arousal cluster. Thus, the greatest symptom reduction was relevant to negative alterations in cognitions and mood and the arousal symptom clusters. This might have been predicted by the emphasis of TIPSS on cognitive processing of beliefs relevant to the trauma and on coping skills. The intrusion and avoidance clusters, however, did not show substantial reductions. While more data is certainly warranted, these findings may demonstrate the promise of the 6-week/12 session TIPSS protocol to substantially decrease PTSD-related negative cognitions and mood as well as arousal while concurrently targeting substance use.

Indeed, in terms of substance use, the participant manifested, via self-report and biochemical verification, significant decreases in both cocaine and alcohol use during the course of treatment. From Session 1 through Session 12 of TIPSS, the participant reported using cocaine on 16 of 42 days (40%). Her final two urinalyses were negative for cocaine, and her self-reported cocaine use decreased to none by the conclusion of treatment. However, since the time between sessions varied, it might be noted that the time between Session 11–12 represented only 1 day. Taken together, the participant reported not using cocaine from immediately prior to Session 10 through Session 12, which amounted to a longest sustained period of abstinence of 10 days. In addition, all of her alcohol breath samples were 0 BAC throughout treatment, and her self-reported alcohol use decreased by approximately 50% over the course of treatment. Notably, while the participant clearly improved and significantly reduced her use of both cocaine and alcohol, she continued to report cocaine use on 40% of days during treatment and alcohol use through the final session date. This underscores the difficult-to-treat nature of SUD, the importance of follow-up periods to assess any further changes in substance use posttreatment, and the need for more intensive SUD treatment (e.g., medication augmentation) options for individuals who manifest challenges in gaining or sustaining abstinence. This also highlights the ability of individuals with PTSD/SUD to commit to treatment and to demonstrate improvements in treatment despite continuing to use substances; ongoing substance use may not be an insurmountable obstacle to effective treatment of PTSD or PTSD/SUD (e.g., Kaysen et al., 2014; McCauley et al., 2012). Unfortunately, no other measures of addiction severity were administered at the conclusion of treatment, which precludes our ability to further interpret the participant’s changes in substance use.

To draw broad-based conclusions about TIPSS, the program will need to be evaluated in the context of a randomized controlled clinical trial, which was recently completed (Vujanovic, et al., 2018). Although this case report illustrates the initial feasibility of TIPSS in reducing PTSD and substance use, the featured participant represents only one individual with a unique history and presenting circumstances. Treatment effects, causality, and long-term well-being outcomes cannot be inferred from this case.

In addition to advancing PTSD/SUD treatment via refinement of extant interventions and development of novel interventions, it is important to note that dissemination and implementation of scientific knowledge in this domain remains a significant issue for scientists and practitioners in this field. As concluded by Simpson et al. (2017), there are “no wrong doors” to PTSD/SUD treatment. While interventions that integrate exposure-based treatment for PTSD with CBT for SUD are recommended, when available (e.g., Roberts et al., 2015; Simpson et al., 2017), research suggests that individuals with PTSD/SUD may benefit from a variety of treatment options, including evidence-based SUD interventions. Increasing clinicians’ knowledge of the psychological and behavioral processes implicated in the etiology and maintenance of PTSD/SUD, as well as the evidence-based principles implicated in evidence-based intervention is imperative. Additional research is necessary to facilitate dissemination and implementation of evidence-based intervention approaches for this challenging population so as to dispel lingering clinician misconceptions and improve institutional support for PTSD/SUD treatment.

Overall, available integrated treatments for PTSD/SUD have primarily combined PE with cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention for SUD (Back, et al., 2014; Najavits & Hien, 2013; Persson et al., 2017; Ruglass et al., 2017; van Dam et al., 2012). This may be important to consider, as dismantling studies have shown that PE and CPT target distinct processes related to PTSD symptomatology (McLean & Foa, 2011; Resick, Galovski, et al., 2008; Resick et al., 2002; Rizvi, Vogt, & Resick, 2009). Specifically, the “active” components of PE have been identified as the exposure elements rather than the cognitive restructuring aspects (Foa et al., 2005), while the “active” components of CPT have been deemed the cognitive therapy aspects (Gallagher, Thompson-Hollands, Bourgeois, & Bentley, 2015). Therefore, this case study adds to the literature by demonstrating that TIPSS represents a promising, novel avenue for treating PTSD/SUD using an integration of well-established evidence-based treatments for PTSD and SUD. Future steps in this domain of inquiry might include a focus on the mechanisms of action and change in effective treatment programs so as to inform transdiagnostic treatment development for SUD and co-occurring conditions.

Highlights.

This case study showcases a novel, integrated cognitive-behavioral treatment approach for posttraumatic stress and substance use disorders.

Novel approach is entitled Treatment of Integrated Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use (TIPSS).

TIPSS integrates cognitive processing therapy with cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorder.

The treatment is comprised of 12, 60-minute individual psychotherapy sessions.

The profiled case demonstrates significant reduction in PTSD symptoms and substance use.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health KL2 Career Development Award (KL2TR000370-07: PI: Vujanovic). The work was also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50 DA009262; PIs: Schmitz, Lane, Green).

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Anka A. Vujanovic, University of Houston

Lia J. Smith, University of Houston

Kathryn P. Tipton, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Joy M. Schmitz, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Brady KT, Jaanimagi U, Jackson JL. Cocaine dependence and PTSD: A pilot study of symptom interplay and treatment preferences. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:351–354. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Foa EB, Killeen TK, Mills KL, Teesson M, Dansky Cotton B, Carroll KM, Brady KT. Concurrent treatment of PTSD and substance use disorders using prolonged exposure (COPE): Patient workbook; therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015;28:489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment. 2016;28:1379–1391. doi: 10.1037/pas0000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Stout RL, Gannon-Rowley J. Substance use disorder-PTSD comorbidity. Patients’ perceptions of symptom interplay and treatment issues. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:445–448. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. A Cognitive–behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction. Rockville, MD: Government Printing Office; 1998. (NIDA NIH Publication No. 98-4308) [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Schumacher JA, Nosen E, Littlefield AK, Henslee AM, Lappen A, Stasiewicz PR. Trauma-focused exposure therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in alcohol and drug dependent patients: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016;30:778–790. doi: 10.1037/adb0000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SA, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, Yadin E. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences, Therapist Guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Yusko DA, McLean CP, Suvak MK, Bux DA, Jr, Oslin D, … Volpicelli J. Concurrent naltrexone and prolonged exposure therapy for patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:488–495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, Cohen JA, Crow BE, Foa EB, Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Kudler HS, Ursano RJ. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:537–552. doi: 10.1002/jts.20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Thompson-Hollands J, Bourgeois ML, Bentley KH. Cognitive behavioral treatments for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: Current status and future directions. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2015;45:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10879-015-9303-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski TE, Harik JM, Blain LM, Elwood L, Gloth C, Fletcher TD. Augmenting cognitive processing therapy to improve sleep impairment in PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84:167–177. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, Wang MC. Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:563–570. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Schumm J, Pedersen ER, Seim RW, Bedard-Gilligan M, Chard K. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with comorbid PTSD and alcohol use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral therapy of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for treatment of borderline personality disorder: Implications for the treatment of substance abuse. NIDA Research Monographs. 1993b;137:201–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. DBT Skills Training Manual. 2. New York: Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA. Addiction, mindfulness, and acceptance. Reno, NV: Context Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy E, Petrakis I. Case report on the use of cognitive processing therapy-cognitive, enhanced to address heavy alcohol use. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:474–478. doi: 10.1002/jts.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley JL, Killeen T, Gros DF, Brady KT, Back SE. Posttraumatic stress disorder and co-occurring substance use disorders: Advances in assessment and treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2012;19 doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Acquilano S, Xie H, Alterman AI, Weiss RD. A cognitive behavioral therapy for co-occurring substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addictive Behavios. 2009;34:892–897. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33:511–525. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Foa EB. Prolonged exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of evidence and dissemination. Expert Reviews in Neurotherapeutics. 2011;11:1151–1163. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles SR, Smith TL, Maieritsch KP, Ahearn EP. Fear of losing emotional control is associated with cognitive processing therapy outcomes in U.S. veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015;28:475–479. doi: 10.1002/jts.22036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Back SE, Brady KT, Baker AL, Hopwood S, … Ewer PL. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:690–699. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Peters L. Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:652–658. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]