Abstract

Among 2,185 Dutch adolescents (ages 11–18), we assessed whether the association among gender nonconformity, homophobic name-calling, and other, general peer victimization differs for boys and girls and for youth with and without same-sex attraction (SSA). We also examined whether sex and sexual attraction differences in the association between gender nonconformity and both types of peer victimization are dependent upon adolescents’ age. Data were collected in the academic year 2011–2012. Results showed that gender nonconformity was positively associated with homophobic name-calling and general peer victimization. These associations were stronger for boys compared with girls and were also stronger with increasing levels of SSA. Sex differences in the relationship between gender nonconformity and general peer victimization were significant for early and middle adolescents, but not for late adolescents. Sexual attraction differences in the relationship between gender nonconformity and both types of peer victimization were significant for early and middle adolescents and not for late adolescents. These results emphasize that key educational messages that address sexual and gender diversity should be delivered during childhood before early adolescence.

Keywords: gender nonconformity, sex, same-sex attraction, age, peer victimization

Gender expression refers to the way in which one expresses one’s gender through characteristics of appearance, personality, and behavior (Institute of Medicine, 2011). A growing body of research suggests that gender-nonconforming youth – those whose gender expression does not conform to cultural norms for their assigned sex at birth– are at increased risk of being victimized by peers at school. This has been found in studies among self-selected samples of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) youth (e.g., Baams, Beek, Hille, & Zevenbergen, 2013; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card, & Russell, 2010) and studies among youth in general (e.g., Aspenlieder, Buchanan, McDougall, & Sippola, 2009; Ewing Lee & Troop-Gordon, 2011; Toomey, Card, & Casper, 2014; Young & Sweeting, 2004).

Youth who are gender-nonconforming also report more mental health problems, such as suicidality and depression, than do their gender-conforming peers (D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Friedman, Koeske, Silvestre, Korr, & Sites, 2006; Roberts, Rosario, Slopen, Calzo, & Austin 2013). Emerging research shows that experiences of victimization contribute to the elevated levels of mental health problems among gender-nonconforming youth (Baams et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Toomey et al., 2010). For example, among LGBT adolescents, peer victimization accounted fully for the negative association between gender nonconformity and psychosocial adjustment (depression, and life-satisfaction; Toomey et al., 2010) and accounted half the increased prevalence of depressive symptoms in gender-nonconforming youth in a large national cohort study (Roberts et al., 2013). Negative experiences with peers may have long-term detrimental effects as gender nonconformity in childhood has been associated with post-traumatic symptoms in early adulthood (Roberts, Rosario, Corliss, Koenen, & Austin, 2012).

The present study builds on this work by assessing the relation between gender nonconformity and various forms of peer victimization and whether this relation is different for youth of different sexes, sexual attractions, and ages.

Biological sex as a moderator of the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization

The majority of studies indicate that gender-nonconforming boys experience more peer victimization than gender-nonconforming girls. (D’Augelli et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2013; Young & Sweeting, 2004; for exceptions see: Toomey et al., 2014). This may be because gender expression is more closely policed by and for men and boys, given that traditional masculinity maintains hegemony (Connell, 1987). Gender-nonconforming girls may not pose the same threat to masculine dominance as do gender-nonconforming boys. As a result, adolescent boys may use peer victimization as a strategy, at a critical stage in the development of their gender identity, to not only regulate the gender expression of their male peers, but also to bolster their own masculinity (Pascoe, 2011; Herek & Mclemore, 2013). For instance, homophobic epithets are more often directed toward boys than toward girls (Collier, Bos, & Sandfort, 2013; Poteat & Espelage, 2005, 2007), in particular when boys do not measure up to expected gender role behaviors (Dominic McCann, Plummer, & Minichiello, 2010; Pascoe, 2011; Swain, 2006).

In the current study we focused specifically on homophobic name-calling not only because research has shown that boys are more likely to be targeted with this type of victimization, but also because homophobic name-calling is one of the most common forms of victimization in schools (Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danischewski, 2016; Poteat & Vecho, 2016). Aside from experiences with homophobic name-calling, we assessed gender nonconformity in relation to a more general form of peer victimization at school (e.g., being pushed/hit at school, or being made fun of by peers). We hypothesized, based on the preponderance of the evidence, that gender nonconformity would be more strongly associated with victimization experiences for boys than for girls.

Sexual orientation as a moderator of the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization

Although sexual minority people are diverse in their gender expressions, gender-nonconforming individuals are often seen by others as gay/lesbian, while gender-conforming individuals are more often seen as heterosexual (Johnson & Ghavami, 2011; Rieger, Linsenmeier, Gygax, Garcia, & Bailey, 2010; Valentova, Rieger, Havlicek, Linsenmeier, & Bailey, 2011). Research on self-selected samples of LGB individuals indicates that LGB people with greater gender nonconformity experience more rejection, including victimization related to being perceived as a sexual minority (Baams et al., 2013; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995; Landolt, Bartholomew, Saffrey, Oram, & Perlman, 2004; Sandfort, Melendez, & Diaz, 2007; Toomey, et al., 2010). Such findings have also been reported in studies of youth in general that did not assess sexual orientation (Aspenlieder et al., 2009; Toomey et al., 2014).

A limitation of these studies, however, is that their sampling design did not allow for exploration of whether gender nonconformity is a unique risk factor for sexual minority youth or also affects the peer relations of non-sexual minority youth. Several studies – conducted primarily in the Netherlands –explored the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization across samples of youth with and without same-sex attractions (SSA). Bos and Sandfort (2015) explored whether gender nonconformity moderated the relationship between SSA and experiences of peer victimization in a sample of 486 adolescents ages 11–17. They found a significant interaction, with SSA more strongly associated with victimization among gender nonconforming youth. In a different study among 1,026 adolescents aged 11–16, a positive relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization was moderated by SSA, meaning that the relationship was significant for adolescents with mean and high levels of SSA, but not for those with low levels of SSA (Van Beusekom, Baams, Bos, Overbeek, & Sandfort, 2016). Although this area of research is developing and one study with older adolescents did not find sexual orientation differences in the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization (Van Beusekom, Roodenburg, & Bos, 2015), we hypothesized that gender nonconformity would be more strongly associated with peer victimization for youth reporting more SSA in our sample, consisting of early, middle, and late adolescents.

The Relationship between Gender Nonconformity and Peer Victimization across Adolescence

In the present study we also address the largely unexplored question of whether the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization changes over the course of adolescence. Early adolescence is a time characterized by an increasing importance of peers (relative to parents) and a greater difficulty with resisting peer influence (Berndt, 1982; Gavin & Furman, 1989; Rose-Krasnor, 1997; Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006; Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Peer group conformity and norms regarding gender and sexuality also become more salient and restrictive during this phase before declining in importance in later adolescence (Gavin & Furman, 1989; Pascoe, 2011). Furthermore, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown that prejudicial attitudes and homophobic behaviors are more frequently reported with the onset of adolescence (Horn, 2006; Poteat & Anderson, 2012; Poteat, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009; Robinson, Espelage, & Rivers, 2013). Older adolescents, meanwhile, are more likely to see social conventions (such as those related to gender expression) in a less rigid way and integrate their understanding of conventions together with individual rights to self-expression (Horn, 2007).

Thus, there is reason based on both developmental theory and empirical research to expect that SSA and gender nonconformity may especially compromise adolescents’ peer relations in early adolescence. However, research in this area has been limited. In their research with older elementary and secondary school students, Aspenlieder and colleagues (2009) expected that school grade would moderate the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization, but did not find this to be the case. Horn (2007) explored differences between middle and late adolescents in their ratings of fictional target figures who varied in terms of sexual orientation and gender expression, but it was not possible to see a developmental effect on acceptance of gender nonconformity because the older participants gave all the figures higher ratings than did the younger participants. In a retrospective study conducted with 96 gay and bisexual young adult men (aged 18–25), Friedman and colleagues (2006) found that the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization was strongest during participants’ middle school years as compared to their elementary and high school years. A limitation of this study is, however, that its sample was small and it relied on retrospective reporting.

The Current Study

In the current study, we explored the relationship between gender nonconformity and peer victimization in a sample of early (11–13 years), middle (14–15 years), and late (16–18 years) adolescents in the Netherlands. Compared with many other countries, the Dutch take a relatively positive stance toward LGB individuals (Kuyper, 2018; Smith, 2011, Widmer, Treas, & Newcomb, 1998) and, similar to other Western countries, levels of negative attitudes toward LGB people and LGB rights have decreased among Dutch citizens over the past years (Kuyper, 2016; 2018). It has been suggested that when homophobia declines, there is less need for men to behave in a traditional masculine way in order to be accepted (Anderson, 2013; McCormack & Anderson, 2010). Youth, and boys in particular, would therefore experience more leeway to express gender-nonconforming behaviors. Dutch people, however, still experience substantial discomfort when same-sex sexuality becomes visible (e.g., when men kiss in public) and also when persons are gender-nonconforming (Kuyper, 2018), which has often been regarded as a visible marker of same-sex sexuality (Valentova et al., 2011). Population based data from the Netherlands show that gender-nonconforming youth are still more frequently victimized by their peers than youth that are gender-conforming (Van Beusekom & Kuyper, 2018). Thus, even though public opinion toward LGB people is relatively positive in the Netherlands compared to other countries, we still expect gender nonconformity to be related to peer victimization in our adolescent sample.

We assessed sex and sexual attraction differences in the association between gender nonconformity and peer victimization. To expand the current literature on this topic, we used two outcome measures: one that assessed adolescents’ experiences with homophobic name-calling and one that assessed experiences of peer victimization more generally. The more fundamental way in which we sought to expand the literature was by exploring how gender nonconformity, biological sex, and sexual attractions are together associated with experiences of peer victimization across stages of adolescence. Given the wide array of psychosocial and health problems associated with the peer victimization of gender-nonconforming youth (see for an overview: Collier, Van Beusekom, Bos & Sandfort, 2013), it is vital to have a better understanding of which youth are particularly at risk and at what time. Understanding this issue offers knowledge about the specific youth to whom attention should be directed and can also have critical implications for the timing of key educational messages that promote the acceptance of gender and sexual diversity.

Two main research questions were addressed:

Is the moderating effect of (biological) sex on the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization dependent upon age?

Is the moderating effect of SSA on the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization dependent upon age?

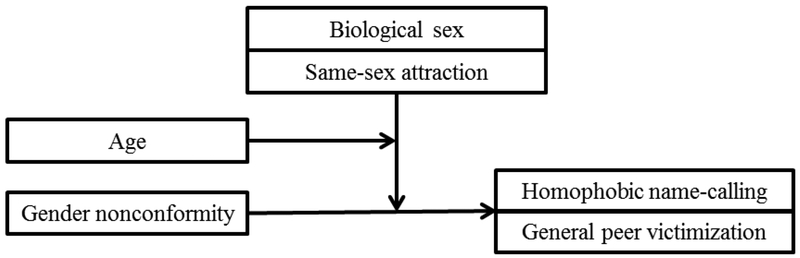

In keeping with the research reviewed above, we expected to find a) that gender nonconformity would be positively associated with experiences of peer victimization, and that this relationship would be stronger among b) boys as compared to girls, and c) youth with higher levels of SSA compared to youth with lower levels of SSA. Given the greater importance of peers and more restricting norms regarding gender and sexuality in early adolescence (Gavin & Furman, 1989; Pascoe, 2011), we expect that sex and sexual attraction differences in the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization will be more pronounced among younger adolescents compared to older adolescents (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual moderated moderation model in wich the effect of gender nonconformity on peer victimization by biological sex and same-sex attraction depend on age.

Method

Participants

The total sample consisted of 2,185 participants (1,069 boys and 1,116 girls). Participants were aged 11 to 18 years (Mage = 15.13, SD = 1.89). The educational background of participants was as follows: 26.4% pre-vocational secondary education or secondary vocational education (low), 30% senior general secondary education (middle), and 43.6% pre-university education (high). In total, 84.2% reported that their parents had a Dutch/Western background and 15.8% reported that their parents were from a non-Western background (at least one parent born in an African, Middle Eastern, Asian, or South-American country).

Procedure

Schools throughout the Netherlands were randomly selected from a listing available on the website of the Netherlands Ministry of Education. We contacted school officials of the selected schools by phone and asked them to participate in a study about gender nonconformity, same-sex attraction, and peer victimization. School officials interested in participating were sent a letter with information about the goals and procedures of the study. Of the 48 schools that were contacted, nine agreed to participate. School officials that decided not to participate often did so because their school was already enrolled in another study (refusal reasons were not systematically collected). Prior to data collection, the board of each school sent a letter to all parents of adolescents younger than 16 years. The letter contained information about the goals and practical procedures of the study and asked parents to contact the researchers if they did not want their children to participate. Non-response from a parent was considered consenting. A total of 17 parents indicated that they did not want their child to participate.

Paper-pencil questionnaires were administered in the school year 2011–2012 during regular class hours, with students seated in arrangements used for exams to maximize privacy as they completed the questionnaires. Research assistants distributed the questionnaires, explained the objective of the study, and stressed the voluntary nature and confidentiality of participation. They informed students that their individual responses would not be shared with their teachers, parents, or fellow students, and emphasized that students could discontinue participation at any time. Students were also asked to seal the questionnaire in an envelope that was collected by research assistants after completion.

The institutional review board of the University of Amsterdam approved the study design and protocol.

Instruments

Gender nonconformity.

We used an adapted version of the Childhood Gender Nonconformity Scale (Collier, Bos et al., 2013; for original scale see Rieger, Linsenmeier, Gygax, & Bailey, 2008) to assess current rather than childhood gender nonconformity. The scale consists of a separate version for boys (example: “I am a feminine boy”) and girls (example: “I am a masculine girl”) and contains six parallel items. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which items were applicable to them (1= absolutely not applicable and 7 = always applicable). A mean score of the six items was computed with a higher score indicating greater gender nonconformity. Cronbach’s alpha was .63 for boys and .70 for girls.

Experiences with homophobic name-calling.

We used a modified version of Poteat and Espelage’s (2005) Homophobic Content Target Subscale to measure participants’ perceived experiences with homophobic name-calling (Collier, Bos et al., 2013). Participants were presented with the following prompt: “Some youth call each other names such as ‘fag,’ ‘homo,’ ‘lesbo,’ or ‘dyke.’ How many times in the past month did the following people call you these names?” Participants indicated on a five-point scale (1 = never and 5 = seven times or more) whether they were called names by various peers at school: (1) a friend; (2) a class member; (3) a fellow student outside your class; (4) someone at your school you do not know; (5) someone you do not like. A mean score of the five items was calculated with a higher score indicating more experiences with homophobic name-calling. Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

General peer victimization.

We assessed experiences with peer victimization in general with nine items from the Peer Role Strain subscale from the Early Adolescent Role Strain Inventory (Fenzel, 1989a, 1989b, 2000). Example items include: “My classmates ignore me” and “My classmates make fun of me at school” (1 = never and 5 = very often). A mean score of the nine items was computed with a higher score reflecting greater exposure to general peer victimization. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale was .86.

Same-sex attraction.

We assessed feelings of same-sex attraction (SSA) with the following single item: “Have you ever experienced romantic and/ or sexual attraction to members of the same sex?” (1 = never and 5 = very often). This item has been widely used in previous studies among same-sex attracted youth (e.g., Collier, Bos et al., 2013).

Statistical analyses

To ensure that the effects of biological sex, SSA, and age as moderating variables could not be attributed to differences in background characteristics, we first carried out chi-square tests and Analyses of Variance (ANOVA). Sex differences in age, levels of gender nonconformity, homophobic name-calling, and general peer victimization were also assessed with ANOVA. Pearson r correlations were conducted to assess the correlations between age, SSA, gender nonconformity, homophobic name-calling, and general peer victimization.

Multiple hierarchical regression analyses were carried out to test the hypotheses that biological sex and SSA moderate the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization (homophobic name-calling and general peer victimization), and to test whether the magnitude of these hypothesized moderations depend on age. These analyses were carried out separately for each dependent variable and potential moderator variable (biological sex and SSA) with use of a PROCESS macro package for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). In Step 1, PROCESS entered, gender nonconformity, the potential moderator variable (biological sex and SSA) and the two-way interactions terms (gender nonconformity × potential moderator variable, gender nonconformity × age, and potential moderator variable × age). Control variables were biological sex (in the analysis with SSA as a moderator), SSA (in the analysis with biological sex as a moderator), cultural background, and education. In Step 2, PROCESS included the three-way interaction term between gender nonconformity × potential moderator variable (biological sex or SSA) × age. Simple slopes for the two-way interactions (gender nonconformity × biological sex and gender nonconformity × SSA) were calculated as described by Jose (2013). In all analyses, age was assessed as a continuous moderator. PROCESS offered the conditional effect of gender nonconformity × biological sex/SSA at values of age in two ways. First, by calculating the significance of values of age equal to a standard deviation below the mean, the sample mean, and a standard deviation above the mean. Adolescents that had an age one standard deviation below the mean, the sample mean, and a standard deviation above the mean were regarded as early, middle, and late adolescents. Second, with the use of John-Newman technique PROCESS calculated when the conditional effects transitioned between significant and nonsignificant along the continuous distribution of age.

Results

Descriptive analyses

No sex differences were found between adolescents with a Western and non-Western ethnic background, χ2 (1, N = 2177) = 1.37, p = .241, and a low, middle, and high educational level, χ2 (2, N = 2185) = 0.03, p = .983. Also, boys and girls did not differ significantly in age and levels of SSA (see Table 1). Boys reported significantly lower levels of gender nonconformity, more homophobic name-calling experiences, and higher levels of general peer victimization compared to girls. One-way ANOVA showed that levels of SSA did not differ significantly between adolescents with a Western (M = 1.19, SD= 0.63) and non-Western cultural background (M = 1.22, SD= 0.75), F = .60, p = .438). However, adolescents attending education at the low (M = 1.23, SD= 0.73) and middle (M = 1.24, SD= 0.73) level did report higher levels of SSA compared to adolescents attending education at the high level (M = 1.13, SD= .52), F = 6.59, p = .001.

Table 1,

Intercorrelations among Age, Gender Nonconformity, Same-sex Attraction, Homophobic Name-calling, and General Peer Victimization

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall group | |||||||

| 1. Age | - | 15.14 | 1.89 | ||||

| 2. Gender nonconformitya | .22*** | - | 1.73e | 0.72 | |||

| 3. Same-sex attractionb | .07** | .22*** | - | 1.19 | 0.65 | ||

| 4. Homophobic name-callingc | −.14*** | .17*** | .16*** | - | 1.39e | 0.65 | |

| 5. General peer victimizationd | −.10*** | .31*** | .18*** | .31*** | - | 1.59e | 0.57 |

| Boys | |||||||

| 1. Age | - | 15.12 | 1.92 | ||||

| 2. Gender nonconformity | .24*** | - | 1.66 | 0.66 | |||

| 3. Same-sex attraction | .09** | .31*** | - | 1.17 | 0.63 | ||

| 4. Homophobic name-calling | −.19*** | .21*** | .16*** | - | 1.58 | 0.75 | |

| 5. General peer victimization | −.13*** | .35*** | .18*** | .35*** | - | 1.64 | 0.58 |

| Girls | |||||||

| 1. Age | - | 15.15 | 1.87 | ||||

| 2. Gender nonconformity | .21*** | - | 1.80 | 0.77 | |||

| 3. Same-sex attraction | .05 | .16*** | - | 1.21 | 0.67 | ||

| 4. Homophobic name-calling | −.09** | .22*** | .22*** | - | 1.22 | 0.49 | |

| 5. General peer victimization | −.08* | .31*** | .19*** | .24*** | - | 1.54 | 0.55 |

Gender nonconformity: 1 = low, 7 = high;

Same-sex attraction: 1 = low, 5 = high;

Homophobic name-calling: 1 = low, 5 = high;

General peer victimization: 1 = low, 5 = high.

ANOVA showed a significant difference between boys and girls.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Adolescents from a non-Western cultural background (M = 14.93, SD= 1.85) were significantly younger than adolescents from a Dutch/Western-cultural background (M = 16.17, SD= 1.78), F = 138.43, p < .0001. Youth attending education at a low (M = 16.13, SD= 1.88) and middle level (M = 15.06, SD= 1.68) were significantly older than those attending education at a high level (M = 14.59, SD= 1.80), F = 133.12, p < .0001.

Table 1 presents the intercorrelations between our studied variables. Gender nonconformity correlated significantly with SSA, homophobic name-calling, and general peer victimization. Youth with greater gender nonconformity reported higher levels of SSA and greater exposure to homophobic name-calling and general peer victimization. Age correlated significantly with gender nonconformity, SSA, homophobic name-calling, and general peer victimization. Adolescents that were older reported greater gender nonconformity and SSA, and lower levels of homophobic name-calling and general peer victimization.

Homophobic name-calling: The moderating roles of biological sex and SSA by age

Results indicated significant main effects for biological sex, age, SSA, and gender nonconformity on homophobic name-calling (see Table 2). Experiences with homophobic name-calling were more frequently reported by boys than girls, younger adolescents compared to older adolescents, and youth with greater levels of SSA and gender nonconformity compared to youth with lower levels of SSA and gender nonconformity.

Table 2,

Biological Sex and Sexual Attraction Differences in the Relations of Gender Nonconformity on Peer Victimization by Age.

| Homophobic name-calling | General peer victimization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | p | B (SE) | β | p | |||

| Moderation by biological sex | ||||||||

| Biological sexa | −.41 (.03) | −.31 | .000 | −.15 (.02) | −.13 | .000 | ||

| Cultural backgroundb | .03 (.04) | .02 | .445 | −.06 (.03) | −.04 | .049 | ||

| Education | −.02 (.02) | −.03 | .142 | −.03 (.01) | −.04 | .058 | ||

| Age | −.07 (.01) | −.21 | .000 | −.06 (.01) | −.19 | .000 | ||

| Gender nonconformity (GNC) | .21 (.02) | .23 | .000 | .27 (.02) | .35 | .000 | ||

| Same-sex attraction (SSA) | .13 (.02) | .13 | .000 | .10 (.02) | .11 | .000 | ||

| GNC × biological sex | −.14 (.04) | −.08 | .000 | −.09 (.03) | −.06 | .006 | ||

| GNC × age | .00 (.01) | −.01 | .718 | .02 (.01) | .04 | .055 | ||

| Biological sex × age | .06 (.01) | .09 | .000 | .02 (.01) | .04 | .054 | ||

| GNC × biological sex × age | .04 (.02) | .04 | .039 | .02 (.02) | .03 | .159 | ||

| R2 = .18, F (9, 2169) = 53,26, p < .001 | R2 = .17, F (9, 2169) = 48,86, p < .001 | |||||||

| ΔR2 due to three-way interaction = .002, ΔF (1, 2168) = 4.88, p = .039 |

ΔR2 due to three-way interaction = .001, ΔF (1, 2168) = 1.99, p = .159 |

|||||||

| Moderation by same-sex attraction | ||||||||

| Biological sexa | −.39 (.03) | −.30 | .000 | −.14 (.02) | −.12 | .000 | ||

| Cultural backgroundb | .02 (.04) | .01 | .509 | −.07 (.03) | −.05 | .025 | ||

| Education | −.03 (.02) | −.03 | .091 | −.03 (.01) | −.04 | .041 | ||

| Age | −.07 (.01) | −.20 | .000 | −.05 (.01) | −.17 | .000 | ||

| Gender nonconformity (GNC) | .18 (.02) | .20 | .000 | .25 (.02) | .32 | .000 | ||

| Same-sex attraction (SSA) | .14 (.02) | .14 | .000 | .09 (.02) | .11 | .000 | ||

| GNC × SSA | .05 (.02) | .07 | .003 | .04 (.01) | .07 | .003 | ||

| GNC × age | .02 (.01) | .04 | .070 | .03 (.01) | .07 | .000 | ||

| SSA × age | −.03 (.01) | −.07 | .003 | .01 (.01) | .02 | .353 | ||

| GNC × SSA × age | −.02 (.01) | −.05 | .029 | −.04 (.01) | −.10 | .000 | ||

| R2 = .18, F (9, 2169) = 53.12, p < .001 | R2 = .17, F (9, 2169) = 49.33. p < .001 | |||||||

| ΔR2 due to three-way interaction = .002, ΔF (1, 2168) = 4.80, p = .029 |

ΔR2 due to three-way interaction = .007, ΔF (1, 2168) = 19.51. p < .001 |

|||||||

Biological sex: boys = 0, girls = 1.

Cultural background: 1 Dutch/Western; 2 = not Western

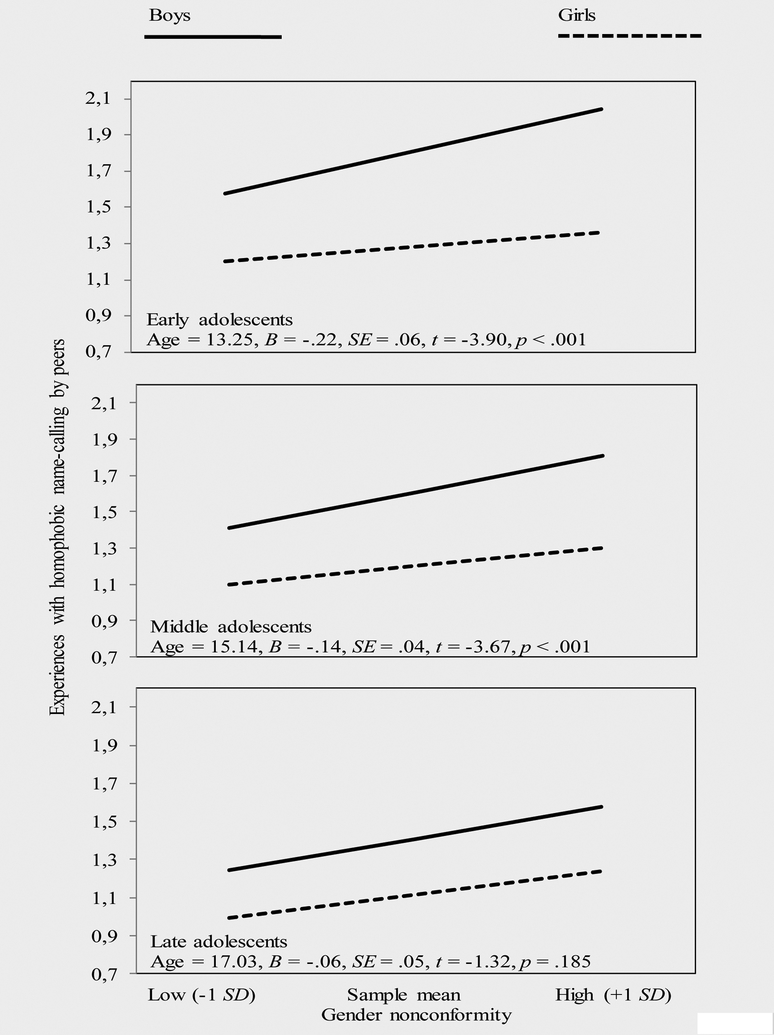

Biological sex moderated the relation between gender nonconformity and homophobic name-calling as evidenced by a significant gender nonconformity × biological sex interaction. Simple slope analysis revealed that the relation was significant for boys (B = .21, p <.001), but not for girls (B = .07, p = .080). The moderating role of biological sex was contingent upon the age of adolescents as demonstrated by a significant three-way interaction of gender nonconformity × biological sex × age. A visual representation of this three-way moderation effect is presented in Figure 2. The results showed that the gender nonconformity × biological sex interaction only held among early and middle adolescents, but not among late adolescents.

Figure 2.

The conditional effect of gender nonconformity on homophobic name-calling as a function of biological sex and age. The three panels for early, middle and late adolescents correspond to values of age equal to a standard deviation below the mean, the sample mean, and a standard deviation above the mean. Similar results were found when using the Johnson-Newman technique: The gender nonconformity × biological sex interaction only held among early and middle adolescents (11 to 16.3 years), but not among late adolescents (16.5 to 18 years).

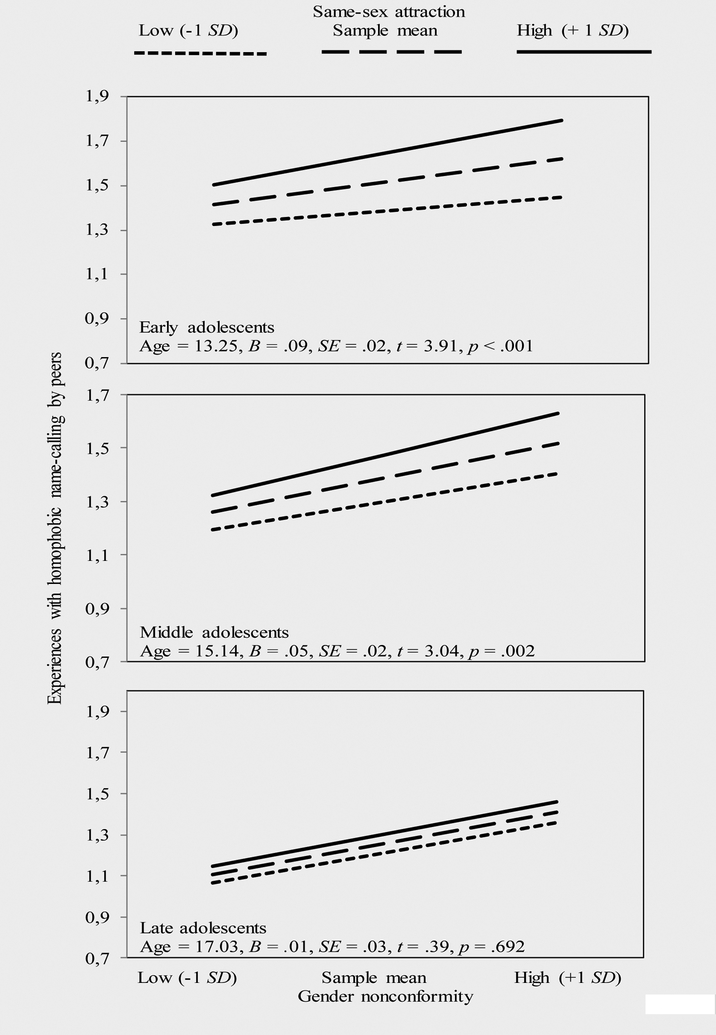

SSA moderated the relation between gender nonconformity and homophobic name-calling as evidenced by a significant gender nonconformity × SSA interaction. Simple slope analysis showed that the strength of the relationship increased when levels of SSA increased: low SSA (mean – 1 SD), B = .15, p < .001; mean SSA, B = .18, p = .001; high SSA (B + 1 SD), B = .21, p < .001. A significant three-way interaction of gender nonconformity × SSA × age supported moderated-moderation. As can be seen in Figure 3, the interaction of gender nonconformity × SSA was significant for early and middle adolescents, but not for late adolescents.

Figure 3.

The conditional effect of gender nonconformity on homophobic name-calling as a function of same-sex attraction (SSA) and age. The three panels for early, middle and late adolescents correspond to values of age equal to a standard deviation below the mean, the sample mean, and a standard deviation above the mean. Similar results were found when using the Johnson-Newman technique: The gender nonconformity × SSA interaction only held among early and middle adolescents (11 to 15.8 years), but not among late adolescents (15.9 to 18 years).

General peer victimization: The moderating roles of biological sex and SSA by age

In the regression models predicting general peer victimization, we found significant main effects for biological sex, age, SSA, and gender nonconformity (see Table 2). Levels of general peer victimization were higher among boys as opposed to girls, younger as opposed to older youth, and youth with higher levels of SSA and gender nonconformity compared to youth with lower levels of SSA and gender nonconformity.

A significant gender nonconformity × biological sex interaction showed that biological sex moderated the relation between gender nonconformity and general peer victimization. Simple slope analysis indicated that the relation between gender nonconformity and general peer victimization was stronger for boys (B = .27, p <.001) than for girls (B = .18, p <.001). A nonsignificant gender nonconformity × biological sex × age interaction showed no evidence of moderated-moderation. That is, the strength of the sex differences found in the relation between gender nonconformity and general peer victimization did not vary along participants’ age.

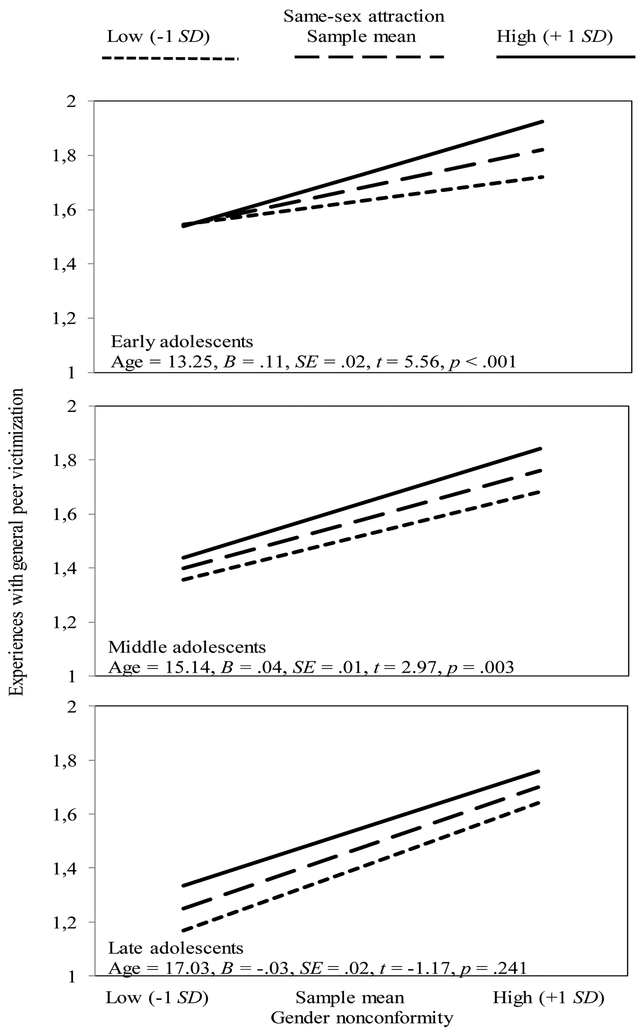

A significant gender nonconformity × SSA interaction indicated that SSA moderated the relation between gender nonconformity and general peer victimization. The relation increased in strength when levels of SSA increased: low SSA (mean – 1 SD), B = .19, p < .001; mean SSA, B = .25, p < .001; high SSA (mean + 1 SD), B = .31, p < .001. Furthermore, we found a significant three-way moderation effect of the gender nonconformity × SSA × age interaction (see Figure 4 for a visual representation). That is, the moderating role of SSA in the relation between gender nonconformity and general peer victimization was only significant for early and middle adolescents, but not for late adolescents.

Figure 4.

The conditional effect of gender nonconformity on general peer victimization as a function of same-sex attraction (SSA) and age. The three panels for early, middle and late adolescents correspond to values of age equal to a standard deviation below the mean, the sample mean, and a standard deviation above the mean. Similar results were found when using the Johnson-Newman technique: The gender nonconformity × SSA interaction only held among early and middle adolescents (11 to 15.5 years), but not among late adolescents (15.5 to 18 years).

Discussion

The current study assessed, among a sample of Dutch adolescents (aged 11–18), whether sex- and sexual attraction-related differences in the relation of gender nonconformity with two types of peer victimization within the school context were dependent upon age. We found that adolescents with high levels of gender nonconformity were more often called homophobic names and experienced more general peer victimization than adolescents with low levels of gender nonconformity. We found these associations to be stronger for boys than for girls and also stronger for youth with high levels of same-sex attraction (SSA) than for youth with low levels of SSA. These findings support converging evidence that gender-nonconforming boys and adolescents with SSA in particular, may be a target for peer victimization (D’Augelli et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2013; Van Beusekom et al., 2016).

Prior research has shown that peer pressure to conform to culturally sanctioned gender roles is high in early childhood, followed by a decrease in middle childhood, and an increase in early adolescence (Alfieri, 1996; Stoddart & Turiel, 1985), a time in which peer relations are becoming more salient (e.g., Rubin et al., 2006; Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the heightened vulnerability to peer victimization for gender-nonconforming boys and gender-nonconforming youth with SSA in early adolescence. We found that sex and sexual attraction differences in the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization were contingent upon age. That is, for early and middle adolescents only, gender nonconformity elicits general peer victimization more strongly among boys than among girls and elicits both homophobic name-calling and general peer victimization more strongly among youth with high levels of SSA when compared with youth with low levels of SSA. Studies have documented that peer victimization related to gender nonconformity is associated with outcomes such as depression, diminished school belonging, traumatic stress and substance use (Collier, Van Beusekom et al., 2013). Our research therefore demonstrates the importance of promoting acceptance of gender diversity and strengthening social support for gender-nonconforming adolescents. Given that gender-nonconforming boys and youth with SSA are especially at risk for peer victimization in early and middle adolescence, youth need to receive age-appropriate messaging about sexual and gender diversity before they enter early adolescence.

Contrary to what we expected, gender nonconformity was more strongly related to general peer victimization for boys, irrespective of their age. Whereas gender nonconformity was equally related to homophobic name-calling among late adolescent boys and girls, the relation was nonsignificant for early and middle adolescent girls. The differences between these findings for boys and girls might be related to the measures we used to assess peer victimization. In contrast to experiences with homophobic name-calling, which is strictly verbal, our measure of general peer victimization assessed a variety of behaviors (e.g., social exclusion and physical victimization). Prior research has shown that homophobic behaviors and sexual prejudice are more common in early adolescence and decline thereafter (Horn, 2006; Poteat & Anderson, 2012; Poteat et al., 2009). Prejudice is thought to be less common among older adolescents as they have developed more complex cognitive skills and therefore rely less on stereotypes (Aboud 1988; Bigler & Liben, 2006). We found both types of peer victimization, but homophobic name-calling in particular, to be negatively correlated with adolescents’ age. As adolescents grow older, they seem less likely to use more overt forms of homophobic victimization (such as homophobic name-calling), which might explain the lack of sex differences found among older adolescents. Older adolescents, in contrast, might still be more likely to use more general forms of victimization to target gender-nonconforming boys.

The increased peer victimization experiences of (young) gender-nonconforming boys as opposed to girls are consistent with the notion that men place more importance to adhering to their gender role than women do (Connell, 1987). Research suggests that boys use (homophobic) victimization, such as name-calling not only as a tool to regulate the gender expression of their male peers, but also reinforce their own masculinity (Dominic et al., 2010; Pascoe, 2011). It has been argued, however, that due to decreasing levels of homophobia, adolescent boys nowadays face fewer gender role pressures and may express their gender more freely (Anderson, 2013; McCormack & Anderson, 2010). In the Netherlands, where our study was conducted, there is an affirming legal context for LGB rights, and public opinion toward LGB individuals is generally positive (Kuyper, 2016; 2018; Smith, 2011). Despite this greater acceptance of LGB people and decline in levels of homophobia over time (Kuyper, 2016; 2018), Dutch adolescents, in particular boys, are still victimized for a nonconforming gender expression.

The absence of sexual attraction differences in the association between gender nonconformity and peer victimization among late adolescents is in agreement with some prior studies of late adolescents’ exposure to peer victimization (Van Beusekom et al., 2013) and mental health outcomes (Rieger & Savin-Williams, 2012). These studies further indicated that gender nonconformity was a stronger predictor of peer victimization and mental health problems than feelings of SSA. It might be that as adolescents grow older and become less prejudiced, they are more likely to accept same-sex attracted peers (Poteat et al., 2009). At the same time, however, they may still experience discomfort with gender-nonconforming peers, irrespective of their sexual attractions. Clearly, more research is needed to understand the complex role that sexual attraction plays in the relation between gender nonconformity and peer victimization across different stages of development.

A key question that remains unanswered is why early and middle adolescents with high levels of gender nonconformity experience more peer victimization when they also report SSA. One explanation might be that the young adolescents’ with SSA in our sample had disclosed their sexual orientation to their peers. Openness about a same-sex sexual orientation has been associated with increased experiences of peer victimization (D’Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002). Being open about one’s sexual attraction and at the same time being gender nonconforming might explain the increased levels of peer victimization. However, we did not assess whether adolescents’ disclosed their sexual orientation to their peers. Although studies from the US and the Netherlands indicate that youth tend to come out at earlier ages compared to youth in previous eras (Russell & Fish, 2016; De Graaf, Van Den Borne, Nikkelen, Twisk, & Meijer, 2017), we do not know for sure whether disclosure of SSA explained the increased risk for peer victimization among young gender-nonconforming adolescents with SSA. Another interpretation could be that if adolescents’ feelings of SSA were unknown by their peers, the observed differences in peer victimization between young gender-nonconforming adolescents with and without SSA, are related to visible differences in gender expression (i.e., via activity choices, appearance, mannerisms) amongst the adolescents in this sample. If so, it would explain why young same-sex attracted adolescents with high levels of SSA and gender nonconformity are particularly at risk for peer victimization.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study was our large sample size with a wide age range that allowed us to contribute to the emerging literature on the quality of gender-nonconforming youths’ peer relations. Our large age range allowed us to reliably assess whether the moderating roles of biological sex and SSA vary upon adolescents’ age. Such an assessment is important as it helps to identify which factors place gender-nonconforming youth at greater risk for peer victimization.

Our current findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, we tested hypotheses about processes that develop over time using cross-sectional data. We conceptualized gender nonconformity as an antecedent of peer victimization while one longitudinal study found that some forms of peer victimization were linked to increases in gender nonconformity over time (Ewing Lee & Troop-Gordon, 2011). Longitudinal research is clearly needed to provide us with a better understanding of how feelings of SSA and gender nonconformity shape adolescents’ peer relations during adolescence.

As previously mentioned, we did not assess whether adolescents disclosed feelings of SSA to others, nor did we assess other indicators of sexual orientation (including same-sex sexual experiences, or self-identification as LGB). Accordingly, we were unable to explore the role of disclosure and other sexual orientation indicators in the relationships described here. The relationship between sexual orientation disclosure and peer victimization in different phases of adolescence is an important area for future research.

Moreover, our measure of homophobic name-calling may not fully capture girls’ experiences with verbal victimization. Adolescents may use different verbal victimization practices to regulate the gender expression of boys compared to girls. For instance, boys in particular use homophobic epithets as a means to target other boys’ gender expression (Pascoe, 2011; Thurlow, 2001). Unlike homophobic epithets directed to boys, both boys and girls might be more likely to direct sexualized insults such as ‘slut’ to girls (Renold, 2002).

Conclusion

An ample body of research has associated peer victimization with serious negative outcomes (see for an overview Collier, Van Beusekom et al., 2013). Our study showed that adolescents with higher levels of gender nonconformity are more likely to be victimized by their peers than adolescents with lower levels of gender nonconformity. Young boys with high levels of gender nonconformity are particularly vulnerable to homophobic name-calling, and boys in general are more likely to experience general peer victimization when they show signs of gender nonconformity. In early and middle adolescence, same-sex attracted boys and girls with high levels of gender nonconformity are also more likely to be victimized and called names than adolescents without SSA that are also gender nonconforming. The timing of interventions and key educational messages that promote sexual and gender diversity is therefore essential and should start before early adolescence.

Funding:

Dr. Sandfort’s contribution to this manuscript was supported by NIMH center grant P30-MH43520 (P.I.: Robert Remien, PhD) to HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Research

References

- Aboud FE (1988). Children and prejudice. New York: Blackwell [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri T, Ruble DN, & Higgins ET (1996). Gender stereotypes during adolescence: Developmental changes and the transition to junior high school. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1129–1137. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E (2013). Adolescent Masculinity in an Age of Decreased Homohysteria. Boyhood Studies, 7, 79–93. doi: 10.3149/thy.0701.79 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenlieder L, Buchanan CM, McDougall P, & Sippola LK (2009). Gender nonconformity and peer victimization in pre-and early adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Science, 3, 3–16. doi: 10.3233/DEV-2009-3103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Beek T, Hille H, Zevenbergen FC, & Bos HMW (2013). Gender nonconformity, perceived stigmatization, and psychological well-being in Dutch sexual minority youth and young adults: A mediation analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 765–773. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0055-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ (1982). The features and effects of friendship in early adolescence. Child Development, 53, 1447–1460. doi: 10.2307/1130071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, & Liben LS (2007). Developmental intergroup theory. Explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 162–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00496.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HMW, & Sandfort TGM (2015). Gender nonconformity, sexual orientation, and Dutch adolescents’ relationship with peers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1269–1279. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0461-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier KL, Bos HMW, & Sandfort TGM (2013). Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 363–375. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9823-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier KL, Van Beusekom G, Bos HMW, & Sandfort TGM (2013). Sexual orientation and gender identity/expression related peer victimization in adolescence: A systematic review of associated psychosocial and health outcomes. Journal of Sex Research 50, 299–317. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.750639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW (1987). Gender and power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, & Starks MT (2006). Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 1462–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, & Hershberger SL (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 148–167. doi: 10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf H, Van Den Borne M, Nikkelen S, Twisk D, & Meijer S (2005). Seks onder je 25e: Seksuele gezondheid van jongeren in Nederland anno 2017. (Sex under 25: Sexual health of youth in The Netherlands anno 2005). Delft: Eburon [Google Scholar]

- Dominic, McCann P, Plummer D, & Minichiello V (2010). Being the butt of the joke: Homophobic humour, male identity, and its connection to emotional and physical violence for men. Health Sociology Review, 19, 505–521. doi: 10.5172/hesr.2010.19.4.505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing Lee EA, & Troop-Gordon W (2011). Peer socialization of masculinity and femininity: Differential effects of overt and relational forms of peer victimization. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 29, 197–213. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-35X.2010.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel LM (1989a). Role strain in early adolescence: A model for investigating school transition stress. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 13–33. doi: 10.1177/0272431689091003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel LM (1989b). Role strains and the transition to middle school: Longitudinal trends and sex differences. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 211–226. doi: 10.1177/0272431689093003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel LM (2000). Prospective study of changes in global self-worth and strain during the transition to middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Koeske GF, Silvestre AJ, Korr WS, & Sites EW (2006). The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin LA, & Furman W (1989). Age differences in adolescents’ perceptions of their peer groups. Developmental Psychology, 25, 827–834. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, & McLemore KA (2013). Sexual Prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS (2006). Heterosexual adolescents’ and young adults’ beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality and gay and lesbian peers. Cognitive Development, 21, 420–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2006.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS (2007). Adolescents’ acceptance of same-sex peers based on sexual orientation and gender expression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 363–371. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9111-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KL, & Ghavami N (2011). At the crossroads of conspicuous and concealable: What race categories communicate about sexual orientation. PLoS One, 6, e18025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE (2013). ModGraph-I: A programme to compute cell means for the graphical display of moderational analyses: The internet version, Version 3.0. Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand: Retrieved from http://pavlov.psyc.vuw.ac.nz/paul-jose/modgraph/ [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Giga NM, Villenas C & Danischewski DJ (2016). The 2015 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L (2016). LGBT Monitor 2016. Opinions towards and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. The Hague, the Netherlands: Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L (2018). Opinions on sexual and gender diversity in the Netherlands and Europe. The Hague, the Netherlands: Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP [Google Scholar]

- Landolt MA, Bartholomew K, Saffrey C, Oram D, & Perlman D (2004). Gender nonconformity, childhood rejection, and adult attachment: A Study of gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 117–128. doi: 10.1023/b:aseb.0000014326.64934.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack M, & Anderson E (2010). “It’s just not acceptable any more’: The erosion of homophobia and the softening of masculinity at an English sixth form. Sociology, 44, 843–859. doi: 10.1177/0038038510375734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe CJ (2011). Dude, You’re a Fag: Masculinity and Sexuality in High School. Berkeley: University of California Press [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington NW, D’Augelli AR (1995). Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology; 23, 33–55. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199501). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, & Anderson CJ (2012). Developmental changes in sexual prejudice from early to late adolescence: the effects of gender, race, and ideology on different patterns of change. Developmental Psychology. 48, 1403–1415. doi: 10.1037/a0026906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, & Espelage DL (2005). Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) Scale. Violence and Victims, 20, 513–528. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.2005.20.5.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, & Espelage DL (2007). Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 27, 175–191. doi: 10.1177/0272431606294839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL, & Koenig BW (2009). Willingness to remain friends and attend school with lesbian and gay peers: Relational expressions of prejudice among heterosexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 952–962. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9416-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, & Vecho O (2016). Who intervenes against homophobic behavior? Attributes that distinguish active bystanders. Journal of School Psychology, 54, 17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renold E (2002). Presumed innocence (hetero)sexual, heterosexist and homophobic harassment among primary school girls and boys. Childhood, 9, 415–434. doi: 10.1177/0907568202009004004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger G, Linsenmeier JA, Gygax L, & Bailey JM (2008). Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: evidence from home videos. Developmental Psychology, 44, 46. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger G, Linsenmeier JA, Gygax L, Garcia S, & Bailey JM (2010). Dissecting “gaydar”: Accuracy and the role of masculinity–femininity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 124–140. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9405-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger G, & Savin-Williams RC (2011). Gender nonconformity, sexual orientation, and psychological well-being. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 611–621. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9738-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, & Austin SB (2012). Childhood Gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics, 129, 410–417. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, Calzo JP, & Austin SB (2013). Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Espelage DL, & Rivers I (2013). Does it get better? Developmental trends in peer victimization and mental health in LGB and heterosexual youth - Results from a nationally representative prospective cohort study. Pediatrics, 131, 423–430. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L (1997). The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development, 6, 111–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00097.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski W., & Parker J (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups In Eisenberg N (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 571–645). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST & Fish JN (2016). Mental health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TGM, Melendez RM, & Diaz RM (2007). Gender nonconformity, homophobia, and mental distress in Latino gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sex Research, 44, 181–189. doi: 10.1080/00224490701263819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW (2011). Cross-national differences in attitudes towards homosexuality. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Monahan KC (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1531–1543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart T, & Turiel E (1985). Children’s concepts of cross-gender activities. Child Development, 32,1241–1252. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.32.6.1129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain J (2006). The role of sport in the construction of masculinities in an English independent junior school. Sport, Education and Society, 11, 317–335. doi: 10.1080/13573320600924841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thurlow C (2001). Naming the “outsider within”: Homophobic pejoratives and the verbal abuse of lesbian, gay and bisexual high-school pupils. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 25–38. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Card NA, & Casper DM (2014). Peers’ perceptions of gender nonconformity. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 34, 463–485. doi: 10.1177/0272431613495446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, & Russell ST (2010). Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a002070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentova J, Rieger G, Havlicek J, Linsenmeier JAW, & Bailey JM (2011). Judgments of sexual orientation and masculinity–femininity based on thin slices of behavior: A cross-cultural comparison. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 1145–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9818-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beusekom G, Baams L, Bos HMW, Overbeek G, & Sandfort TGM (2016). Gender nonconformity, homophobic peer victimization, and mental health: how same-sex attraction and biological sex matter. The Journal of Sex Research, 53, 98–108. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.993462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beusekom G, Kuyper L (2018). The LGBT-monitor 2018: The life situation of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the Netherlands. The Hague, the Netherlands: Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP [Google Scholar]

- Van Beusekom G, Roodenburg S, Bos HMW (2015) Seksuele aantrekking en gender non-conformiteit In: Van Aken M, Beyers W, Deković M, Geeraets M, De Graaf H, Reitz E (Eds) Intieme relaties en seksualiteit, (pp. 77–88). Bohn Stafleu van Loghum, Houten. doi: 10.1007/978-90-368-0968-9_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widmer ED, Treas J, & Newcomb R (1998). Attitudes toward nonmarital sex in 24 countries. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 349–358. doi: 10.1080/00224499809551953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, & Sweeting H (2004). Adolescent bullying, relationships, psychological well-being, and gender-atypical behavior: A gender diagnosticity approach. Sex Roles, 50, 525–537. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000023072.53886.86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]