Abstract

Objective:

This study examined the role of depressive symptoms in mediating the relationship between early life experiences of racial discrimination and accelerated aging in adulthood for African Americans (i.e., prediction over a 19-year period; from age 10 to 29) after adjusting for gender and health behaviors.

Methods:

Longitudinal self-report data over seven waves of data collection from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS) were utilized. The sample included 368 African Americans with usable gene expression data to compute accelerated aging, and complete data on all self-report variables including racial discrimination (Schedule of Racist Events) and depression (DISC-IV). Blood was collected by antecubital blood draws from participants at age 29. The proposed model was tested by path analysis.

Results:

Findings revealed that high discrimination at ages 10–15 was associated with depression at age 20–29 (β = .19, p = .001), controlling for depression at ages 10–15, which, in turn, was related to accelerated cellular level aging (β = .11, p = .048) after controlling for gender, alcohol consumption, and cigarette use. The indirect effect of racial discrimination on aging through depression at age 20–29 was significant β = .021[.001, .057], accounting for 32.3% of the total variance.

Conclusion:

These findings support research conceptualizations that early life stress due to racial discrimination lead to sustained negative affective states continuing into young adulthood that confer risk for accelerated aging, and possibly premature disease and mortality in African Americans. These findings advance knowledge of potential underlying mechanisms that influence racial health disparties.

Keywords: discrimination, health, racism, African Americans, aging

Research findings have suggested that early life stressful experiences have a lasting impact on biological risk for disease and premature mortality due to chronic diseases of aging (Berg et al., 2017). Increasingly, researchers have suggested that early life exposure to psychosocial stressors may influence negative affective states (e.g., depression), and have effects on poor physical health through physiological dysregulation and increased wear and tear on body systems over time (Leger, Charles, & Almeida, 2018; Tomfohr, Pung, & Dimsdale, 2016).

An early and pervasive stressor related to health and mental health for African Americans is racial discrimination (Lewis et al., 2015). Racial status is said to be one of the first social categories that young children learn, preceded only by learning to distinguish sex (Quintana, & McKown, 2012). In addition, recent research with youth suggests particularly strong effects of early exposure to discrimination (Gibbons et al., 2014), possibly due to stimulation of “fight or flight” responses and chronic vigilance for danger, disrupting the body’s regulatory systems leading to increased vulnerability to chronic disease and depression (Williams et. al., 2003). Physical dysregulation (e.g., autonomic nervous system dysfunction), particularly dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis, has also been associated with psychosocial stress and disease. Consistent with this process, Geronimus (2001) hypothesized that due to repeated exposure to race-related stressors, African Americans would be “weathered” with greater exposure associated with increased acceleration of biological aging.

To measure accelerated aging, a recently developed gene expression index of aging developed by Peters et al. (2015) was utilized. This transcriptome index consists of 1497 sites where the level of gene expression (amount of mRNA) is associated with increasing age. The sites included in the transcriptome index are located in gene pathways with known aging mechanisms including metabolic functioning, immune senescence, and mitochondrial decline. This suggests that the transcriptome index assesses gene expression patterns of functional significance for aging, and is associated with other biomarkers of metabolic/cardiovascular risk for chronic illness such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and body mass index (Peters et al., 2015). Accordingly, the transcriptome index appears well suited to capture the process of accelerated aging and resulting risk for premature expression of chronic diseases of aging among African Americans and others.

Research also has established an association between depression and chronic conditions, especially cardiovascular disease (Penninx, 2017), with recent work indicating an association of major depression with accelerated aging (Han et al, 2018). In addition, sustained and chronic negative affective states in response to daily stressors are related to increases in chronic health conditions and functional limitations across 10 years (Leger, Charles, & Almeida, 2018). Smith-Bynum et al. (2014) examined longitudinal trajectories of racial discrimination experiences among African Americans and found that African American adolescents who reported higher levels of discrimination were four times more likely to be in an increasing depression trajectory than were African American youth that reported consistently low levels of discrimination. Together these findings suggest the need to test the mediating role of sustained increases in depression on accelerated aging in an African American sample.

The current study builds on previous research demonstrating a link between racial discrimination and accelerated aging (Lee, Kim, & Neblett, 2017). This study also utilizes a sample that has been well characterized in prior reports. The present study hypothesized that racial discrimination would be related to accelerated aging such that a greater frequency of racial discrimination experiences during childhood would be associated with accelerated aging in adulthood for African Americans. This study also hypothesized that depressive symptoms would mediate the relationship between racial discrimination and accelerated aging. Gender was controlled for in this study due to previous research demonstrating gender differences in the report of stressful experiences that can influence health (Bale & Epperson, 2015).

Method

Participants

The hypotheses for the current study were tested using participants from the longitudinal Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), a multisite and non-clinical study of neighborhood and family effects on health and development in African American families (see Gibbons et al. 2014). Participants were recruited from rural, suburban, and metropolitan communities. Youth and their families were approached for participation in FACHS when youth were in the fifth grade (Mean age = 10.56).

Procedures

The protocol and all study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Georgia and Iowa State University. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the study respondents. To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American university students and community members served as field researchers to collect data from the families in their homes. Audio-enhanced, computer-assisted, self-administered interviews (ACASI) were used to assess all self-report material. At Wave 7 a certified phlebotomist performed antecubital blood draws at each participant’s home using a PAXgene tube. Samples were kept frozen at −80° until used for the analyses described below. All (N = 470) available samples were checked for quality and usability at the Rutgers repository. For further description of the FACHS sample and recruitment, see Appendix I.

Measures

Racial discrimination.

At the first wave of data collection, the target youths completed the 13-item revised version of the Schedule of Racist Events (SRE; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996) to assess frequency of specific discriminatory behaviors during the past year, including racially based slurs, insults, and physical threats. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .82.

Depressive Symptoms ages 10 to 15.

At each wave (1, 2, and 3) from ages 10 to 15, target youths completed the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Version 4 (DISC-IV) to assess frequency (all yes/no) of feeling sad, irritable, tired, restless, or worthless; and, other depressive symptoms (e.g., “In the last year, was there a time when you… often felt sad or depressed?”). Cronbachs alpha for this measure exceeded .83 for each wave of data collected.

Depressive Symptoms ages 20 to 29.

In adulthood (wave 5,6, and 7), depression was assessed using the nine-item Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) measure of depressive symptoms. Respondents were asked to report (0 = no; 1 = yes) whether they experienced symptoms of depression (e.g., “felt sad, empty, or depressed most of the day”) for at least a 2-week period in the past year. The Cronbach Alpha for the scale was .83.

Control Variables age 29.

Health-related covariates were statistically controlled for in this study in order to exclude plausible rival explanations. In adulthood (wave 7) alcohol consumption was measured by asking “During the past 12 months, how often have you had a lot to drink, that is 3 or more drinks at one time?” Also in adulthood (wave 7) cigarette use was measured by asking “How many cigarettes have you smoked in the last 3 months?” The response categories ranged from 1 (0 days) to 5 (all 7 days).

Transcriptional Index of biological age.

Biological age was measured using the transcriptomic clock developed by Peters et al. (2015). After excluding samples with poor quality (n = 81) and samples excluded because of no amplification (n = 3), the Rutgers repository identified a total sample of N = 386 young adults with usable samples. Probe data yielded a microarray data set of 47,323 probes, which was filtered by removing probes with detection threshold of p ≤ 0.05, leaving 44,846 probes for analysis. After quantile normalization data was log2 transformed and inspected visually for batch effects. Transcriptomic age was calculated using publicly available software (https://trap.erasmusmc.nl). Mean biological age was 29.49 (SD = 0.22). Accelerated aging was determined using the residual scores from the regression of biological age on chronological age. These residuals had a mean of zero, with positive scores indicating accelerated aging (for further information see Appendix II).

Analytic strategy

Initial data cleaning was conducted using SPSS; descriptive statistics and characterization of intercorrelations were conducted using Mplus; Path modeling in Mplus was used to test the model. Steiger’s root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .05) and the comparative fit index (CFI > .90) were used to assess goodness-of-fit of the model. To evaluate the significance of the hypothesized indirect effect, the 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated with bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping with 1,000 replications.

Results

All (N = 470) participants in the final sample with both self-report and a blood draw at age 29 (Mean age = 29.49) self-identified as Black or African American. Of these, 368 provided usable data regarding gene expression as well as responses to all self-report data and comprise the final analytic sample. The final sample (63% female) can be characterized as low to moderate in annual income (M = $20,991.39), with moderate average educational attainment, with 91% graduating HS. In addition, most were employed (80.2%), had health insurance (79.3%), and had 0.72 children on average, with 64.4% of participants reporting a committed romantic partner relationship at age 29. Supplemental Table T1 displays means, standard deviations, and the zero-order correlation among the study variables. There was a significant correlation between racial discrimination and young adult depression (r = .236, p =.000). Young adult depression was significantly correlated with aging (r = .133, p =.011). The control variables showed no correlation with aging.

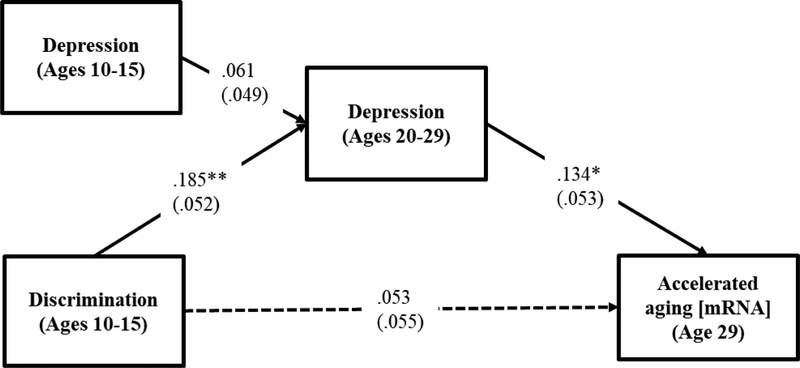

The results of the examination of indirect effects of racial discrimination on aging through youg adult depression (age 20–29) can be seen in Figure 1. The various fit indices, using root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA < .05) and the comparative fit index (CFI >.90), suggest that the model provides a good fit to the data (χ2(1)=1.716, p = .1902; RMSEA=.044; CFI = .986). Racial discrimination is related to young adult depression (β = .185, CI= [.084, .286] , p = .000), which, in turn, is related to aging (β = .134, CI = [.028, .242] , p = .011) after controlling for gender, alcohol consumption, and cigarette use.

Figure 1.

Effects of early racial discrimination (ages 10 – 15) on accelerated aging (age 29) mediated through young adult depression (ages 20–29). Not shown, effects of sex, alcohol consumption, and cigarette use are controlled in these analyses. The indirect effect is significant β = .030[.008, .070]

Note. Chi-square = 1.716, df = 1, p = .1902; CFI = .986; RMSEA = .044. Values are standardized parameter estimates and standard errors are in parentheses. **p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05 (two-tailed tests), n = 368.

The test of the indirect effect of racial discrimination on aging through young adult depression was significant β = .025, with a 95% confidence interval of [.005, .062], accounting for 32.05% of the total variance.

Discussion

A main objective of this research was to longitudinally examine the role of depressive symptoms as a mechanism influencing the relationship between early life experiences of racial discrimination and accelerated aging among African Americans. Consistent with the study hypothesis, experiences of racial discrimination during childhood (age 10–15) contributed to accelerated aging in adulthood (age 29), and effects were mediated through their impact on increased depressive symptoms in young adulthood (age 20–29), even when controlling for the effects of gender and health behaviors (i.e., alcohol consumption and cigarette use). The current findings are consistent with the hypothesis that poor health and health disparities during adulthood may result from stressful experiences earlier in life, such as early experiences of racial discrimination (Williams, et al., 2003). These findings also suggest that when African American children experience racial discrimination their appraisal/coping responses could be depressive states, and in turn, these depressive states can influence biological risk in adulthood. Taking a life course perspective, this study highlights the need to consider childhood as a sensitive period during development whereby stressful adverse experiences, like racial discrimination, are biologically embedded in body systems in a lasting form that makes some African American children more susceptible to poor health later in life (Umberson et al., 2014). One marker of this biological embedding may be elevated level of depressive symptoms in young adulthood, suggesting a potential area of therapeutic intervention.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study makes several contributions to the available literature, some limitations should be noted. First, a limitation involves the sample utilized for the study. This study focused on African Americans living in towns and small cities and therefore it was not a nationally representative sample. Second, the study did not provide diagnoses of depression and so effects attributed to depression may be due to negative affective processes more generally rather than being specific to depressive symptoms. Finally, the model tested was a simple mediational model and did not examine the range of potential buffers and resilience processes that may serve to protect against the effect of early racial discrimination exposures. Conversely, it also did not examine potential additive or multiplicative effects attributable to additional sources of early stress or developmental vulnerabilities. Future studies should address this complexity, and better map the influence of different adverse experiences and protective processes on accelerated aging among marginalized and underserved populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD080749), the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (R01HL118045), the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA021898). In addition, support for this study was provided by the Center for Translational and Prevention Science (P30DA02782) funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bale TL, & Epperson CN (2015). Sex differences and stress across the lifespan. Nature neuroscience, 18(10), 1413 10.1038/nn.4112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg MT, Simons RL, Barr A, Beach SRH, & Philibert RA (2017). Childhood/Adolescent stressors and allostatic load in adulthood: Support for a calibration model. Social Science and Medicine, 193, 130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT (2001). Understanding and Eliminating Racial Inequalities in Women’s Health in the United States: The Role of the Weathering Conceptual Framework. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 56, 133–6, 149–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng C-Y, Gerrard M, Cutrona C, Wills TA, & Stock M (2014). Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: a differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychology, 33(1), 11 10.1037/a0033857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, Chan RF, Hattab MW, Shabalin AA, … Penninx BWJH (2018). Epigenetic Aging in Major Depressive Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S (2013). DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology, 14(R115):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhävä J, Pedersen NL, & Hägg S (2017). Biological age predictors. EBioMedicine, 21, 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22(2), 144–168. 10.1177/00957984960222002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Kim ES, & Neblett EW Jr (2017). The link between discrimination and telomere length in African American adults. Health Psychology, 36(5), 458 10.1037/hea0000450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger KA, Charles ST, & Almeida DM (2018). Let It Go: Lingering Negative Affect in Response to Daily Stressors Is Associated With Physical Health Years Later. Psychological Science. 10.1177/0956797618763097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, & Williams DR (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual review of clinical psychology, 11, 407–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH (2017). Depression and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiological evidence on their linking mechanisms. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MJ, Joehanes R, Pilling LC, Schurmann C, Conneely KN, Powell J, … Singleton AB (2015). The transcriptional landscape of age in human peripheral blood. Nature Communications, 6 10.1038/ncomms9570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, & Mckown C (2012). Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child. 10.1002/9781118269930 [DOI]

- Smith-Bynum MA, Lambert SF, English D, & Ialongo NS (2014). Associations between trajectories of perceived racial discrimination and psychological symptoms among African American adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 26(4), 1049–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr LM, Pung MA, & Dimsdale JE (2016). Mediators of the relationship between race and allostatic load in African and White Americans. Health Psychology, 35, 322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Thomas PA, Liu H, & Thomeer MB (2014). Race, Gender, and Chains of Disadvantage. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 20–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.