Abstract

Objectives:

To examine the relationship between registered nurse (RN) burnout, job dissatisfaction and missed care in nursing homes.

Design:

Cross-sectional secondary analysis of linked data from the 2015 RN4CAST-US nurse survey and LTCfocus.

Setting:

540 Medicare and Medicaid-certified nursing homes in California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

Participants:

687 direct care RNs

Measurements:

Emotional Exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, job dissatisfaction, missed care

Results:

30% of RNs exhibited high levels of burnout, 31% were dissatisfied with their job, and 72% reported missing one or more necessary care tasks on their last shift due to lack of time or resources. One in five RNs reported frequently being unable to complete necessary patient care. Controlling for RN and nursing home characteristics, RNs with burnout were five times more likely to leave necessary care undone (OR = 4.97, 95% CI 2.56-9.66) than RNs without burnout. RNs who were dissatisfied were 2.6 times more likely to leave necessary care undone (OR=2.56, 95% CI 1.68-3.91) than RNs who were satisfied. Tasks most often left undone were comforting/talking with patients, providing adequate patient surveillance, patient/family teaching, and care planning.

Conclusion:

Missed nursing care due to inadequate time or resources is common in nursing homes, and is associated with RN burnout and job dissatisfaction. Improved work environments with sufficient staff hold promise for improving care and nurse retention.

Keywords: workforce, burnout, job satisfaction, registered nurses, nursing home

Introduction

Burnout and occupational stress among healthcare workers are increasingly being recognized as significant threats to patient safety and care quality.1-8 The National Academy of Medicine is particularly focused on this issue and in 2017 launched the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience to address it.9 Characterized as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion and cynicism,10 burnout in healthcare workers has been found to be an independent predictor of adverse events,4 medical errors,7 healthcare-associated infection,2 and malpractice suits.6 Both burnout and job dissatisfaction have been linked to poor patient satisfaction.3,5,8

Registered nurses (RNs) in the United States working in nursing homes report higher rates of burnout and job dissatisfaction than RNs employed in any other setting, including hospitals,3 yet little is known about how this impacts care quality. A 2014 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office of Inspector General report found that roughly one in five Medicare beneficiaries receiving post-acute care in nursing homes from 2008 to 2012 experienced adverse events resulting in harm.11 Just over two-thirds of these events were classified as preventable due to inadequate monitoring, failure to provide necessary treatments, substandard treatment, or inadequate/incomplete care plans.11 These are care activities which all fall under the leadership of RNs who are responsible for supervising other nursing personnel, managing medications, coordinating care and organizing care plans, conducting patient surveillance, and overseeing infection control and wound care programs in this setting.12,13

Extensive evidence from hospitals has shown that when RNs work with insufficient staff and resources in poor safety climates, they are more likely leave necessary patient care undone.14-16 This phenomenon, also known as “missed care” or “unfinished nursing care”, has been found to be a predictor of worse care quality, increased adverse events, and decreased patient satisfaction.16 Burnout among hospital RNs has been identified as an important mediator in the relationship between work environment and patient safety outcomes, suggesting that supportive work environments enable nurses to be engaged with their work, and thus more able to ensure safe care.4 These relationships are less well understood in nursing homes.

Studies of missed care in nursing homes have been done primarily outside of the U.S. with samples comprised largely of nursing assistants rather than licensed nurses.17-22 These studies have shown that lower staffing, poor teamwork and safety climate, higher work stress, and increased resident acuity contribute to missed care;17-20 and that nursing staff who miss care are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion and rate care quality poorly.21,22 With the exception of one study17 however, these did not measure care tasks specific to licensed nurses such as care coordination, medication administration, patient/family teaching, and treatment/procedure completion. Also, structural and cultural differences in the way nursing home care is provided in different countries limits generalizability of these findings to the U.S.. The only study to our knowledge that examined missed care among U.S. nursing home RNs found that failure to provide adequate surveillance or administer medications on time was associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection.23

Research on nursing home staff burnout has also mostly come from abroad without particular focus on licensed nurses.24 While one expects that similar factors contribute to burnout and missed care for nursing assistants, licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and RNs in nursing homes, the latter have unique clinical leadership roles that warrant examining them separately. Staffing and resource adequacy, supportive managers,25-27 compensation,25,27 RN engagement in organizational affairs,26 and promotional opportunities25 have been found to contribute to RN job satisfaction in U.S. nursing homes. Yet there is still poor understanding as to how job satisfaction and burnout relate to patient safety in this setting. In this study, we explore an element of this relationship by examining how burnout and job dissatisfaction contribute to the likelihood of nursing home RNs leaving necessary care undone. We hypothesized that both burnout and job dissatisfaction would be associated with greater likelihood of missed care.

Methods

Design and Data Sources

This study was a cross-sectional secondary analysis of 2015 RN4CAST-US nurse survey data from California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Aiken and colleagues28,29 conducted the survey from January to December 2015 to examine the relationships between organizational nursing factors and care quality across healthcare settings. They surveyed a 30% random sample of licensed RNs in each of the four states, a total of 231,000 RNs, using mail and email addresses on file with the state boards of nursing. Nurses were asked to provide their employers’ names and addresses so that their responses could be linked to the employers. This design avoids response bias at the organizational level that can occur when surveying RNs through their employers. The final response rate was 26%, reflecting a growing trend of non-response to mailed surveys,30 and the challenge of getting respondents to complete a 12 page questionnaire. A subsequent survey of a random sub-sample of 1,400 non-responders achieved an 87% response rate and yielded no significant differences on measures of interest between responders and non-responders to suggest response bias.31 The non-responder survey featured a shorter questionnaire, more intensive efforts to contact RNs, and a small cash incentive. These survey methods have been described in detail elsewhere.28,31

RN4CAST-US data were linked with LTCfocus,32 a publicly-available data set from Brown University, to provide organizational characteristics of the nursing homes in which RNs were employed. LTCfocus merges data from the Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reports system, Minimum Data Set, Medicare claims, Nursing Home Compare, and other sources.32 We used the 2015 facility-level LTCfocus file downloaded from http://ltcfocus.org.

Study Population

Of the parent survey respondents, 2.6% or 1,540 RNs worked in nursing homes, a similar proportion to that of RNs employed in nursing homes across the U.S.. We identified these RNs by cross-matching employer names and addresses of respondents with a list of Medicare and Medicaid-certified nursing homes in the four states. We excluded RNs in administrative or other non-direct care positions (n=853), since the missed care measure is specific to direct care activities. Though nursing home RNs in management roles often provide some clinical care, we had no way of distinguishing who among these had purely administrative duties and who provided direct care from the survey. Thus, we included only RNs who specifically reported their position as direct care, yielding a final sample of 687 direct care RNs employed across 540 nursing homes.

Variables and Measures

Burnout.

Burnout was measured using the Emotional Exhaustion subscale of the Maslach-Burnout Inventory, a validated standardized tool for assessing occupational burnout.10 Nurses indicated how frequently they experienced nine feelings of emotional exhaustion using a seven point scale (1=never to 7=every day). Higher total composite scores correspond with higher burnout. Nurses were classified as having burnout if their score was equal to or greater than 27, the published average for healthcare workers.33

Job dissatisfaction.

Nurses reported the degree to which they were satisfied with their primary job using a four point scale ranging from “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied”. They were also asked about specific job aspects including healthcare, retirement, and tuition benefits, salary/wages, work schedule, opportunities for advancement, independence at work, and professional status. Nurses who answered “very dissatisfied” or “somewhat dissatisfied” were considered to be dissatisfied.

Missed care.

Nurses were asked to identify from a list of 14 care activities which, if any, were necessary but left undone due to lack of time or resources on their most recent shift/day worked. This question captures both clinical and planning/communication activities and has been developed iteratively by an expert panel of nurse researchers and survey methodologists.34,35 The activities include: adequate patient surveillance, oral hygiene/mouth care, on time medication administration, treatments/procedures, skin care, pain management, ambulation/range of motion, adequate documentation, care coordination, comfort/talking with patients, preparing patients and families for discharge, developing/updating care plans, teaching/counseling patients and families, and participating in team discussions. Nurses were considered to have missed care if they left one or more activities undone. An additional single survey item asked RNs whether they were frequently unable to complete necessary care due to lack of time or resources.

Covariates.

We controlled for RN and nursing home characteristics in our adjusted models. Nurse characteristics came from the survey and included: age, years of RN experience, sex, race, native language, and highest nursing degree. Nursing home characteristics came from LTCfocus and included: ownership type, chain affiliation, bed size, payer mix, and staffing measures for RNs, LPNs, and certified nursing assistants.

Statistical Analysis

We generated descriptive statistics to examine characteristics of sample RNs and nursing homes. Next, we generated a series of robust logistic regression models to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted effects of burnout and job dissatisfaction on missed care, accounting for clustering of RNs within nursing homes. We began with bivariate models, added in RN characteristics, then nursing home characteristics to achieve our final models. Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). The University of Pennsylvania institutional review board approved this study.

Results

Table 1 depicts characteristics of sample RNs. The first column summarizes all RNs in the sample, while the second and third columns show only those RNs with job dissatisfaction and burnout. The job dissatisfaction and burnout groups are not mutually exclusive, meaning that an RN who scored as positive for both would appear in both groups. Thirty-one percent of RNs were dissatisfied with their jobs and 30% exhibited burnout. The only statistically significant demographical difference between the groups was that dissatisfied RNs were more likely native English speakers relative to the total sample. Missed care rates were significantly higher for RNs with job dissatisfaction and burnout. Across all RNs, 72% reported missing one or more care tasks on their last shift due to lack of time or resources. Eighty-three percent of RNs with job dissatisfaction, and 95% of RNs with burnout reported missing care. Characteristics of the nursing home employers are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Registered nurse (RN) characteristics for total sample, RNs with job dissatisfaction, and RNs with burnout.

| Total sample | RNs with job dissatisfaction |

RNs with burnout | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Registered nurses, n(%) | 687 (100%) | 212 (30.9%) | 204 (29.7%) |

| Age in years, mean(SD) | 49.1 (13.1) | 47.8 (12.9) | 47.4 (12.6) |

| Years of RN experience, mean(SD) | 16.6 (14.0) | 14.9 (13.3) | 15.2 (12.8) |

| Sex, female, n(%) | 637 (92.7%) | 196 (92.5%) | 182 (89.2%) |

| Race, non-white, n(%) | 237 (34.5%) | 73 (34.4%) | 70 (34.3%) |

| Native language, English, n(%) | 511 (74.4%) | 172 (81.1%)* | 164 (80.4%) |

| Highest nursing degree1, n(%) | |||

| Hospital diploma | 102 (14.8%) | 25 (11.8%) | 23 (11.3%) |

| Associate's degree | 321 (46.7%) | 109 (51.4%) | 106 (52.0%) |

| Bachelor's degree | 247 (36.0%) | 72 (34.0%) | 66 (32.4%) |

| Master's degree or higher | 9 (1.3%) | 4 (1.9%) | 6 (2.9%) |

| Missed care2 | 494 (71.9%) | 175 (82.5%) * | 194 (95.1%) * |

Category differs from total sample (p<.05) based on a two sample two-sided t-test for continuous variables, or a Pearson chi2 test for categorical variables

Percentages do not sum to 100% due to missing data

Missed care refers to whether the RN indicated that one or more of the following care tasks were necessary but left undone on his/her last shift due to lack of time or resources: adequate patient surveillance, oral hygiene, adequate documentation, medications administered on time, treatments and procedures, skin care, pain management, care coordination, comfort/talk with patients, preparation of patients/families for discharge, care plan development/update, patient/family teaching, ambulation or range of motion, and participation in team discussions.

Table 2.

Nursing home employer characteristics (n=540)

| Ownership, for profit, n(%) | 335 (62.0%) |

| Chain-owned facility, n(%) | 303 (56.1%) |

| Total beds, mean (SD) | 136 (85) |

| Payer mix, mean (SD) | |

| % primary payer Medicaid | 55.8 (25.2) |

| % primary payer Medicare | 15.4 (12.6) |

| Staffing measures, mean (SD) | |

| RN hours per resident day | 0.65 (0.36) |

| LPN hours per resident day | 0.80 (0.40) |

| CNA hours per resident day | 2.50 (0.50) |

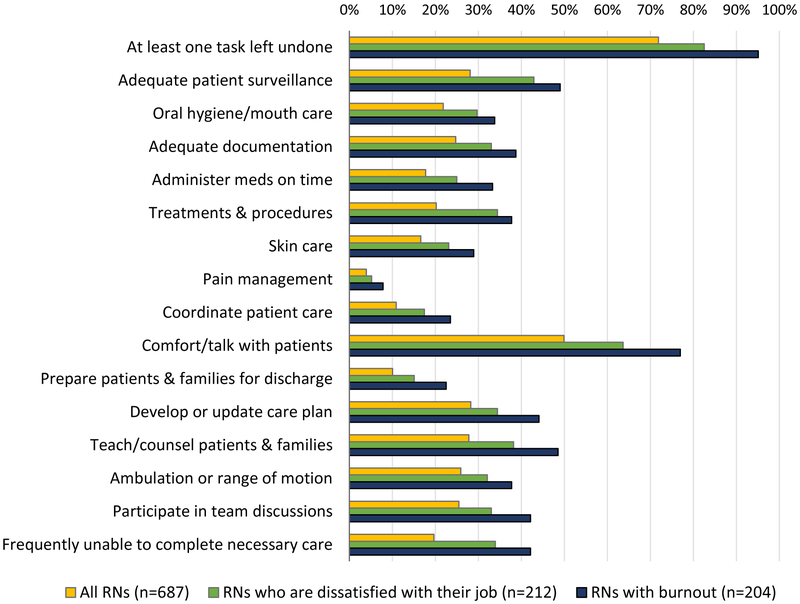

Figure 1 shows care activities RNs reported leaving undone, comparing the total sample of RNs to those with job dissatisfaction and those with burnout. Across all activities, RNs with burnout were most likely to leave care undone. The activity most often missed was comforting/talking with patients, which 50% of the total sample, 64% of RNs with job dissatisfaction, and 77% of RNs with burnout reported leaving undone. Adequate patient surveillance, teaching/counseling patients and families, and developing/updating care plans were the next three activities most often missed. Pain management was the least missed activity, with only 4% of RNs in the overall sample reporting leaving this undone, suggesting that when faced with limited time and resources, RNs likely prioritize this activity. Forty-two percent of RNs with burnout and 34% of RNs with job dissatisfaction reported frequently being unable to complete necessary care, compared to 20% of the overall sample.

Figure 1.

Percentage of registered nurses (RNs) who report being unable to complete necessary care tasks due to lack of time or resources

Results of unadjusted and adjusted robust logistic regression models showing the effects of burnout and job dissatisfaction on missed care are shown in Table 3. Controlling for RN and nursing home characteristics, RNs with burnout were five times more likely to leave necessary care undone (OR = 4.97, 95% CI 2.56–9.66) than RNs without burnout, while RNs who were dissatisfied with their jobs were 2.6 times more likely to leave necessary care undone (OR=2.56, 95% CI 1.68–3.91) than RNs who were satisfied. All results were significant at the p <.001 level.

Table 3.

Effects of registered nurse (RN) burnout and job dissatisfaction on missed care (n=687)

| Bivariate | Adjusted for RN characteristics |

Adjusted for RN and nursing home characteristics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) p-value | ||||||

| Burnout | 5.53 (2.79-10.96) | <.001 | 5.41 (2.79-10.50) | <.001 | 4.97 (2.56-9.66) | <.001 |

| Job dissatisfaction | 2.33 (1.55-3.49) | <.001 | 2.60 (1.71-3.93) | <.001 | 2.56 (1.68-3.91) | <.001 |

Note: Odds ratios indicate the odds of registered nurses (RNs) with vs. without burnout, and with vs. without job dissatisfaction reporting the outcome in bivariate and adjusted robust logistic regression models. Models account for clustering of RNs within nursing homes. Missed care measures whether the RN indicated that one or more of the following care tasks were necessary but left undone on his/her last shift due to lack of time or resources: adequate patient surveillance, oral hygiene, adequate documentation, medications administered on time, treatments and procedures, skin care, pain management, care coordination, comfort/talk with patients, preparation of patients/families for discharge, care plan development/update, patient/family teaching, ambulation or range of motion, and participation in team discussions. RN characteristics: age, sex, race, years of experience, educated in U.S. or abroad, native language. Nursing home characteristics: bed size, for-profit vs. nonprofit/government ownership, chain affiliation, Medicaid census, Medicare census; RN, licensed practical nurse (LPN), and certified nursing assistant (CNA) hours per resident per day.

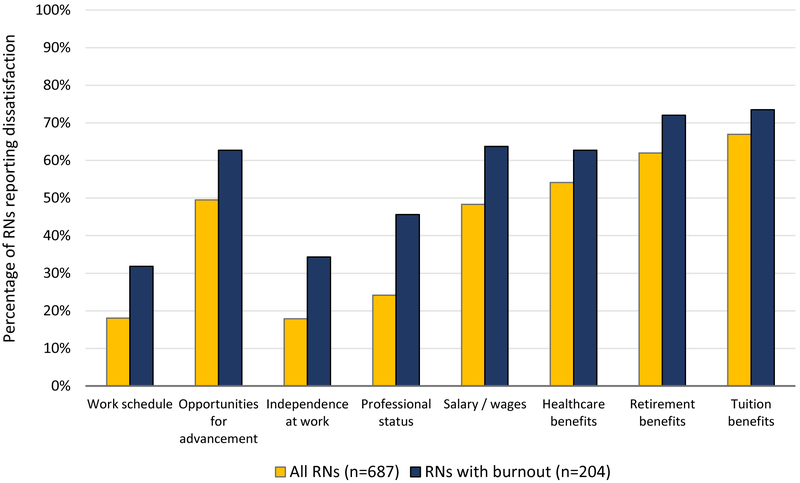

Figure 2 depicts specific job aspects with which RNs were dissatisfied, showing RNs with burnout (n=204) relative to all RNs (n=687). The most prominent areas of dissatisfaction across all RNs were with tuition, retirement, and healthcare benefits (67%, 62%, and 54% of RNs, respectively), opportunities for advancement (49% of RNs), and salary/wages (48% of RNs). Nurses with burnout had higher rates of dissatisfaction across all job aspects, but differed the most from RNs overall in professional status (46% of RNs with burnout vs. 24% of RNs overall) and independence at work (34% of RNs with burnout vs. 18% of RNs overall).

Figure 2.

Dissatisfaction with various job aspects among all registered nurses (RNs), and RNs with burnout

Discussion

Findings from this study indicate that nursing home RNs are often unable to complete needed nursing care due to inadequate time or resources, and that missed care is more common among RNs with high burnout or job dissatisfaction. This raises significant concerns for patient safety as well as nurse retention in nursing homes. One in five RNs in our sample reported frequently being unable to complete necessary patient care. Nurses with burnout were five times more likely to miss needed care than RNs without burnout, while RNs who were dissatisfied were 3.5 times more likely to miss care than RNs who were satisfied.

These findings add context to the 2014 DHHS Office of Inspector General report which attributed the majority of nursing home adverse events to inadequate monitoring, failure to provide necessary or appropriate treatments, or inadequate/incomplete care plans.11 These are clinical activities that all fall under the leadership of RNs.12,13 Yet among RNs in our study, 28% said they lacked the time or resources to perform adequate patient surveillance, 20% left treatments or procedures undone, and 28% left care plans unfinished. Among RNs with burnout or job dissatisfaction, these rates were even higher: 49% of RNs with burnout and 43% of RNs with job dissatisfaction said they could not provide adequate patient surveillance; 38% of RNs with burnout and 34% of RNs with job dissatisfaction left treatments or procedures undone; and 44% of RNs with burnout and 34% of RNs with job dissatisfaction left care plans unfinished.

The same DHHS report found that over a third of adverse events were medication-related, with the most common events being medication-related hypoglycemia, mental status changes, and falls/trauma due to medication side effects.11 In our study, 33% of RNs with burnout and 25% of RNs with job dissatisfaction said they were unable to administer medications on time, a key aspect of medication safety. Potential consequences of this include interacting medications being given too closely together, or mealtime-sensitive medications being given without regard to food, increasing the risk for side-effects. Feeling rushed during medication administration also increases the risk for errors, particularly since nursing home nurses typically administer medications to large numbers of patients while being frequently interrupted.36 When RNs cannot provide adequate surveillance, they may miss signs of adverse effects like mental status changes that should prompt intervention.

We cannot determine with the data available the causal pathways between nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction, and missed care. In this study we examined missed care as our dependent variable, but other cross-sectional studies across various settings have shown that nurses and nursing assistants experience greater dissatisfaction when they are unable to complete necessary care or feel that they are providing poor quality care.25,37,38 It is likely that these are closely interdependent concepts. That is, working in under-resourced settings generates stress for nurses who realize that needed nursing care is being missed, which in turn generates additional stress for feeling that they cannot provide better quality care. Creating better work conditions with sufficient resources both supports nurses to provide higher quality care and allows nurses to feel more in control of their work. While the main focus of this paper is patient care quality and safety, the high rates of RN burnout and dissatisfaction we find raise concerns about attracting and retaining an adequate RN workforce in nursing homes.

The National Academy of Medicine has recognized that organizational and health system factors play important roles in promoting clinician well-being and improving patient safety.1,39 Extensive evidence has shown that RNs are more satisfied and experience less burnout when they have adequate staff and resources, supportive managers, productive colleague relationships, input into organizational affairs, and opportunities for advancement.4,25-27,40-42 Nursing homes unfortunately function under very real financial constraints due to heavy reliance on Medicaid, making it challenging for administrators to hire more staff and offer competitive salaries and benefits. Still, the costs of salary and benefit adjustments must be balanced against additional labor costs for training, recruitment, and productivity loss generated by high turnover.

Even under tight fiscal constraints, nursing home leaders can take steps to improve work environments through a variety of evidenced-based interventions.26,42-44 Creating a culture that emphasizes root-cause analysis of systemic problems rather than punishing nurses for individual mistakes could help identify inefficiencies in systems and protocols that result in missed care. Involving RNs in quality improvement committees, having administrators consult with direct care staff on solutions to organizational problems, and having formal processes for responding to employee concerns could also help identify problems and improve employee engagement. Finally, offering career ladders, preceptor programs for new hires, leadership training, and continuing education could improve two areas of dissatisfaction among RNs in our study: opportunities for advancement and professional status.

A few limitations of our study should be noted. First, the cross-sectional design of the study prevents us from drawing conclusions as to causal relationships between our variables of interest. Second, there are more than 15,000 nursing homes in the U.S.45 which may limit generalizability of our findings, though our sample still included hundreds of RNs employed across 540 nursing homes in four states. Finally, by excluding RNs in administrative roles, we lost more than half of our original sample of survey respondents from our analysis. Often RNs serving as directors of nursing, supervisors, or in other administrative roles in nursing homes do provide some direct care. However, since we were unable to determine from the survey who among respondents had purely administrative duties versus a mix of both administrative and clinical duties, we included only direct care RNs for the cleanest sample.

In summary, RNs serve vital roles in overseeing the safety and quality of care in nursing homes, yet most RNs report not having enough time or resources to provide necessary care, raising significant concerns for patient safety. A large number of RNs in this setting experience burnout and job dissatisfaction, and missed care is even more prevalent among these individuals. Work environments that provide adequate staff and resources, involve RNs in quality improvement processes, and support RNs through career pathways and leadership opportunities could help to promote employee engagement, reduce missed care, and improve patient safety in nursing homes.

Editor’s Note.

This study provides a timely evaluation of critically important issues in improving care and patient safety in U.S. nursing homes. Nursing burnout, job dissatisfaction, and missed care have been studied in U.S. hospitals, but there has been a paucity of data on these measures in U.S. nursing homes. The data presented provide a sobering view of the work life of registered nurses (RNs) in this setting. RNs represent the health professionals responsible for the vast majority of hands-on care for this complex, vulnerable, and increasingly ill patient population, and the data should raise a clarion call to health policy makers and those who own and manage nursing homes. About one-third of respondents reported burnout and/or job dissatisfaction, and an astounding 72% indicated that they had missed one or more necessary care tasks on their last shift due to lack of time or resources. RNs who reported burnout were five times more likely to report missed care.

Although the study did not directly measure threats to patient safety or actual patient harm, we don’t need to await future studies to recognize that these issues will inevitably lead to patient harm that is potentially preventable. Nursing homes are required to have a minimum number of RN hours per patient, and these hours are an important component of the five-star quality rating system. Over the last year this measure has been improved by changing from a self-reported number to a value based on the facility’s payroll journal. But the number of nursing hours is only one piece of the puzzle. Adequate and competitive pay is obviously another. As the authors suggest, involvement of RNs in quality improvement processes, and support for RNs through career pathways and leadership opportunities are critically important to improving the current situation.

Another factor can also play a role: involvement of well-trained and committed physicians (including certified medical directors), advance practice clinicians (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), pharmacists, rehabilitation therapists, social workers, and other health care professional in a strong, collaborative inter-professional team. This will lead to better quality of care, and better quality of life for nursing home patients as well as the staff who care for them.

‐Joseph G. Ouslander, MD

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s Role: This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research, T32 NR-007104 (Aiken, PI) and R01 NR-014855 (Aiken, PI). The funding organization had no role in the design, methods, data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research, T32 NR-007104 (Aiken, PI) and R01 NR-014855 (Aiken, PI).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout Among Health Care Professionals: A Call to Explore and Address This Underrecognized Threat to Safe, High-Quality Care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Wu ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care–associated infection. Am J Infect Control 2012;40(6):486–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laschinger HKS, Leiter MP. The impact of nursing work environments on patient safety outcomes - The mediating role of burnout/engagement. J Nurs Admin 2006;36(5):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leiter MP, Harvie P, Frizzell C. The correspondence of patient satisfaction and nurse burnout. Soc Sci Med 1998;47(10):1611–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213(5):657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010;251(6):995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke SP, Vargas D. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care 2004;42(2 Suppl):II57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. National Academy of Medicine (online). Available at: https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- 10.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General. Adverse Events in Skilled Nursing Facilities: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Washington DC: 2014. DHHS Publication No. OEI-06–11-00370. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montayre J, Montayre J. Nursing work in long-term care: An integrative review. J Gerontol Nurs 2017;43(11):41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGilton KS, Bowers BJ, Heath H, et al. Recommendations from the International Consortium on Professional Nursing Practice in Long-Term Care Homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17(2):99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalisch BJ. Missed nursing care: a qualitative study. J Nurs Care Qual 2006;21(4):306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalisch BJ, Landstrom GL, Hinshaw AS. Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2009;65(7):1509–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones TL, Hamilton P, Murry N. Unfinished nursing care, missed care, and implicitly rationed care: State of the science review. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52(6):1121–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson J, Willis E, Xiao L, Blackman I. Missed care in residential aged care in Australia: An exploratory study. Collegian 2017;24(5):411–416. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knopp-Sihota JA, Niehaus L, Squires JE, Norton PG, Estabrooks CA. Factors associated with rushed and missed resident care in western Canadian nursing homes: a cross-sectional survey of health care aides. J Clin Nurs 2015;24(19–20):2815–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons SF, Durkin DW, Rahman AN, Choi L, Beuscher L, Schnelle JF. Resident characteristics related to the lack of morning care provision in long-term care. Gerontologist 2013;53(1):151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zúñiga F, Ausserhofer D, Hamers JPH, Engberg S, Simon M, Schwendimann R. The relationship of staffing and work environment with implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss nursing homes - A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52(9):1463–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zúñiga F, Ausserhofer D, Hamers JP, Engberg S, Simon M, Schwendimann R. Are staffing, work environment, work stressors, and rationing of care related to care workers’ perception of quality of care? A cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16(10):860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhaini SR, Zúñiga F, Ausserhofer D, et al. Are nursing home care workers’ health and presenteeism associated with implicit rationing of care? A cross-sectional multi-site study. Geriatr Nurs 2017;38(1):33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson ST, Flynn L. Relationship between missed care and urinary tract infections in nursing homes. Geriatric Nursing 2015;36(2):126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costello H, Walsh S, Cooper C, Livingston G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2018:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castle NG, Degenholtz H, Rosen J. Determinants of staff job satisfaction of caregivers in two nursing homes in Pennsylvania. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi J, Flynn L, Aiken LH. Nursing practice environment and registered nurses’ job satisfaction in nursing homes. Gerontologist 2012;52(4):484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lapane KL, Hughes CM. Considering the employee point of view: Perceptions of job satisfaction and stress among nursing staff in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8(1):8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sloane DM, Smith HL, McHugh MD, Aiken LH. Effect of changes in hospital nursing resources on improvements in patient safety and quality of care: A panel study. Med Care 2018;56(12):1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Barnes H, Cimiotti JP, Jarrín OF, McHugh MD. Nurses’ and patients’ appraisals show patient safety in hospitals remains a concern. Health Affair 2018;37(11):1744–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Research Council. The growing problem of nonresponse In: Tourangeau R, Plewes TJ, eds. Nonresponse in Social Science Surveys: A Research Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013:166. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasater KB, Jarrín OF, Aiken LH, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, Smith HL. A methodology for studying organizational performance: A multi-state survey of front line providers. Med Care In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LTCfocus: Long-term Care: Facts on Care in the US. Brown University School of Public Health (online). Available at: http://ltcfocus.org/. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 33.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory manual. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lake ET, Germack HD, Viscardi MK. Missed nursing care is linked to patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional study of US hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25(7):535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruyneel L, Li B, Ausserhofer D, et al. Organization of hospital nursing, provision of nursing care, and patient experiences with care in Europe. Med Care Res Rev 2015;72(6):643–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson MS, Gruneir A, Lee M, et al. Nursing time devoted to medication administration in long-term care: clinical, safety, and resource implications. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57(2):266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalisch B, Tschannen D, Lee H. Does missed nursing care predict job satisfaction? Journal of Healthcare Management 2011;56(2):117–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishop CE, Squillace MR, Meagher J, Anderson WL, Wiener JM. Nursing home work practices and nursing assistants’ job satisfaction. Gerontologist 2009;49(5):611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine. Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm 2008;38(5):223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lake ET. The nursing practice environment: Measurement and evidence. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64(2 Suppl):104S–122S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lake ET. Development of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health 2002;25(3):176–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwendimann R, Dhaini S, Ausserhofer D, Engberg S, Zuniga F. Factors associated with high job satisfaction among care workers in Swiss nursing homes - a cross sectional survey study. BMC Nurs 2016;15(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flynn L, Liang Y, Dickson GL, Aiken LH. Effects of nursing practice environments on quality outcomes in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(12):2401–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Total Number of Certified Nursing Facilities. Kaiser Family Foundation (online). Available at: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/number-of-nursing-facilities/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed February 20, 2019.