Abstract

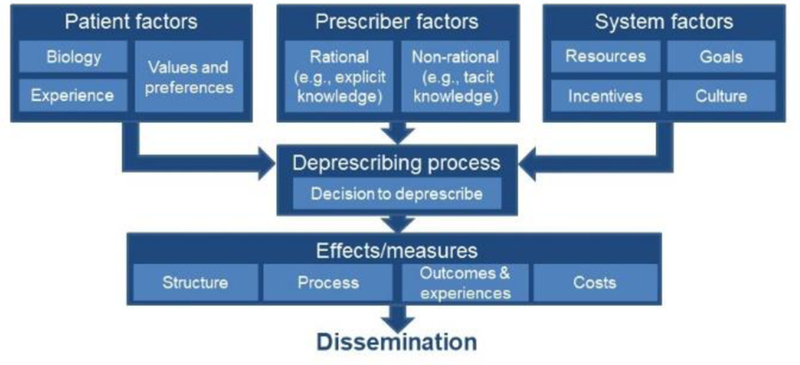

Polypharmacy is common in older adults and associated with inappropriate medication use, adverse drug events, medication nonadherence, higher costs, and increased mortality compared to those without polypharmacy. Deprescribing, the clinically supervised process of stopping or reducing the dose of medications when they cause harm or no longer provide benefit, may improve outcomes. Although potentially beneficial, clinicians struggle to overcome structural, organizational, technological, and cognitive barriers to deprescribing, limiting its use in clinical practice. Deprescribing science would benefit from a unifying conceptual framework to prioritize research. Current deprescribing conceptual frameworks have made important contributions to the field, but often with a focus on specific medication classes or aspects of deprescribing. To further this relatively nascent field, we developed a broader deprescribing conceptual framework that builds upon prior frameworks and includes patient, prescriber, and system influences; the process of deprescribing; outcomes; and dissemination. Patient factors include patients’ biology, experience, values, and preferences. Prescriber factors include rational (e.g., based upon explicit knowledge) and non-rational (e.g., behavioral tendencies, biases, and heuristics) decision-making. System factors include resources, incentives, goals, and culture that contribute to deprescribing. The framework separates the deprescribing decision from the deprescribing process. The framework captures the results of deprescribing by examining changes in clinical structures, performance processes, patient experience, health outcomes, and cost. Through testing and refinement, this novel, more comprehensive conceptual framework has the potential to advance deprescribing research by organizing the existing evidence, identifying evidence gaps, and categorizing deprescribing interventions and the settings in which they are applied.

Keywords: Polypharmacy; Implementation Science; Health Services for the Aged; Economics, Behavioral; Clinical Decision Making

Introduction

Ninety percent of United States (US) adults aged 65 and older take at least one prescription medication, and over 42 percent are exposed to polypharmacy (commonly defined as receipt of five or more medications).1 Polypharmacy increases the likelihood of being prescribed high-risk medications and the likelihood that high-risk medications will lead to adverse drug events (ADEs).2, 3 While polypharmacy can be indicated and appropriate (e.g., when treating patients with multi-morbidity), it is also associated with drug-drug interactions, medication nonadherence, falls, higher overall costs of care, and increased mortality.4

Deprescribing is the clinically supervised process of stopping or reducing the doses of medications that could cause harm or that no longer provide benefits that outweigh potential risks.5, 6 That is, in contrast to patient non-adherence, deprescribing occurs under the initiation and/or guidance of a healthcare provider. Withdrawing specific medication classes is not harmful in most older adults,7, 8 and it may even yield positive outcomes, such as reductions in cognitive decline, falls, hospital admissions, and potentially mortality.9

There are numerous barriers to its implementation in clinical practice despite the potential benefits of deprescribing.10, 11 Patient-level barriers include reluctance to stop medications viewed as necessary for health, receipt of care from multiple providers, and limited experience with deprescribing.12, 13 Provider and system-level barriers include time constraints within clinical encounters; limited incentives to clinicians to stop medications; electronic health records (EHRs) that facilitate initiation, but not discontinuation of medications; fragmented care across clinicians and health systems; inapplicability of disease-specific performance metrics to older patients with multiple chronic conditions; uncertainty about benefits and harms of specific medications; and fear of adverse drug withdrawal events.14

Rigorous evidence to guide deprescribing is limited, with few high-quality or comparative trials and little research focused on patient-centered outcomes. This data gap is especially problematic in the US, with the majority of deprescribing clinical trials (at the time of this writing) recruiting in countries other than the US.15 Because there are many individuals (e.g., patients, clinicians) and health care settings (e.g., ambulatory clinics, long-term care) that can be targets of interventions to facilitate deprescribing, the deprescribing research agenda would benefit from a unifying conceptual framework that incorporates aspects of other frameworks and is specifically focused on organizing the science of deprescribing. In the following section, “Prior Frameworks of Deprescribing,” we describe multiple currently available frameworks intended to help advance the practice of deprescribing, each of which has made important contributions to the field. We then build on these frameworks by developing a unifying and comprehensive framework to advance the science of deprescribing research to foster the design, conduct, and dissemination of deprescribing trials. This new framework clearly delineates definitions of deprescribing (e.g., does deprescribing include therapeutic substitution, dose reduction, or other mechanisms?), separates the potential differential contribution of the deprescribing decision from the deprescribing process, includes team members beyond physicians and pharmacists, and addresses the potential for either rational or non-rational (“behavioral”) interventions to address cognitive barriers that prevent deprescribing.

Defining Deprescribing

The consistency of deprescribing frameworks is predicated on a consensus definition of deprescribing itself. Page et al. conducted a concept analysis of the word “deprescribing,” defining core elements based upon published literature on deprescribing in older people.16 They found that several definitions have been more commonly referenced or adapted for use in studies: Scott et al. defined deprescribing as “a systematic process of identifying and reducing or discontinuing drugs in instances in which existing or potential harms outweigh existing or potential benefits, taking into account the patient’s medical status, current level of functioning, and values and preferences.”10 Meanwhile, Reeve et al. defined deprescribing as a “process of tapering or withdrawing drugs with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes.”17 However, many research studies have either modified these characterizations (e.g., “systematic process of stopping ineffective medications”) or did not cite any established definition. Without a consensus definition of deprescribing, it will be difficult to compare research across studies and settings. While the work of settling on a definition of deprescribing is not yet complete, hereafter, “deprescribing” will most closely reflect the definition by Scott et al.10

Prior Frameworks of Deprescribing

Current literature discusses the overarching concepts related to deprescribing, processes of conducting this in practice, barriers and facilitators to doing so, and recommendations for development of guidelines. The following is a more detailed discussion of each of these facets of deprescribing.

Several existing conceptual models provide general concepts related to appropriate medication use and prescribing decisions. Ouellet et al. describes a larger framework of the benefit and harms of medications, with a need to find a balance for each patient.18 Holmes also provides a general framework related to medication use in older adults, illustrating the competing forces on four aspects of care: life expectancy, time-until-benefit, treatment target, and goals of care.19

Other conceptual models focus more on the process of deprescribing, using multiple process maps, guidelines or protocols, mostly explicating the discrete steps a clinician must complete to successfully discontinue a medication. A recent review identified two models and nine tools that address the entire medication list and four tools that address specific medications (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, benzodiazepine receptor agonists, and antipsychotics).20 Tools varied in their development, with many based on expert opinion and/or without existing strong evidence to support their benefit in clinical practice. Of the two models, one guided medication discontinuation for patients with limited life expectancy,21 and the other described an approach for assessing pharmacotherapy.22 Another review by Scott and colleagues identified seven deprescribing algorithms intended to aid in reviewing an entire medication regimen for potential deprescribing opportunities; however, each had limited evidence of effectiveness.23 Several of these included steps to identify a patient’s medications, their indications, known adverse effects, and assessment of risk with continued use. Mangin et al. also discuss multiple approaches to address inappropriate medication use, including electronic interventions as well as tools that are implicit (e.g., Good Palliative Geriatric Practice algorithm) and explicit (e.g., Beers criteria).24–26

As additional examples, Bain et al. introduced a revision to a point-of-care, provider-oriented prescribing framework that adds the step “Consider Discontinuing Medication.”27 Scott et al. provides an “evidence-based 10-step discontinuation guide” that directs clinicians to include the step, “define overall care goals.”28 Reeve et al. takes a complementary approach and illustrates a five-step patient-centered deprescribing process.5

Published frameworks contain various barriers and facilitators of deprescribing. Existing models only partially capture the multiple factors identified by key participants (e.g., including patient clinical characteristics but omitting cost-related issues) in deprescribing, offering specific leverage points upon which to intervene. Some patient-related frameworks are based upon concepts of patient self-management and medication adherence.16, 18 Reeve et al. identified patient-related barriers (e.g., fear) and enablers (e.g., dislike of medications) to deprescribing, and how these can be affected by the appropriateness of cessation, the process of cessation, and the influence of others.13 Linsky et al. used qualitative methods to understand these patient factors, which fell into three overarching domains: Conflicting Views of Medication, which discusses patients’ general interest in taking fewer medications but simultaneously wanting potential health benefits from medications; Importance of Patient-Provider Relationships, including how trust in a provider influences willingness to deprescribe; and Limited Experience with deprescribing.29 Other frameworks take the perspective of clinicians, such as that by Anderson, who conducted a systematic review that categorizes barriers and enablers into Awareness, or insight; Inertia, which is failing to act even when cognitively recognizing the need; Self-Efficacy related to confidence and ability; and Feasibility, referring to factors external to the provider.30 Linsky et al. used qualitative methods to identify medication, patient, provider, and system factors that either fostered or hindered deprescribing, as viewed from the providers perspective.31

Lastly, to advance the science of deprescribing, Farrell et al. developed a framework for development of deprescribing guidelines via an 8-step systematic process.32

Development of a Novel Conceptual Framework

This multiplicity of factors that influence deprescribing poses a challenge for investigators and health system leaders who design interventions to support deprescribing. They might wonder on which barriers to address or medications to focus or approach to take: Where to start? How can we prioritize them? Which ones can be addressed on their own, and which ones have interdependencies that imply that they need to be addressed as groups? Answering these questions is important to prioritizing research, designing interventions, and, in turn, improving practice. The conceptual frameworks, algorithms, and tools described above each address important components of deprescribing. But there is a need for a more comprehensive conceptual framework – one that encompasses all the steps of deprescribing, their logical relationships, maps the existing literature, and identifies areas where relatively little is known. This need also extends to the proper planning and conduct of clinical trials of deprescribing, which will benefit from a unifying conceptual framework on which to base interventions and dissemination of findings.

To develop a novel, more comprehensive model, we summarized and explored the current literature related to deprescribing, including concepts of appropriate prescribing, polypharmacy, and medication discontinuation. We then met to draft an initial model, building upon components of currently available models, with a goal of creating a unifying model that could be adapted to the needs of individual care delivery systems or researchers. We iteratively revised the draft based upon written and verbal communication, with feedback from multiple experts in geriatrics, polypharmacy, and deprescribing until we achieved consensus.

Components of a Novel Deprescribing Conceptual Framework

Our conceptual framework (Figure) includes patient, prescriber, and system factors that might impact the decision and ability to deprescribe, and is partially drawn from several previously published models.18, 27, 30, 33, 34 Patient factors include biology, or the risks and benefits of each medication for each individual patient, in the context of their health conditions and other medications they are taking; past experience with each drug, including perceived benefits, side effects, burden (which may be influenced by specific medication factors, such as pill characteristics or frequency of dosing), expense, and prior deprescribing or other interruptions in treatment. Experience also includes the “financial toxicity of treatment,”35 and out-of-pocket drug expenses, which have not been explicitly included in prior conceptual frameworks. Clinician knowledge of patients’ values and preferences are essential for shared decision-making, as outlined in the deprescribing logic model by Farrell et al.33

Figure.

Conceptual Model

Prescriber factors include both rational and behavioral (non-rational) components. Rational decision-making is based on prescriber explicit knowledge, beliefs, skills, and preferences.30, 36 Behavioral factors include prescriber decision tendencies (e.g., heuristics, biases) that reflect tacit knowledge.37 Behavioral factors influencing prescriber behavior are rarely, if ever, explicitly included in any existing frameworks, except “inertia” in the earlier Anderson framework.30 Including prescriber behavioral factors is a key innovation of this conceptual framework. Behavioral nudges that address non-rational aspects of medication management have improved prescribing.38

System factors that affect the feasibility of deprescribing include, but are not limited to, resources (e.g., time for shared decision-making, availability of multidisciplinary staff [e.g., nurses, social workers], community resources [e.g., availability of complementary and integrative health care options]);30, 36 institutional goals and culture (which can influence whether a system’s leadership prioritizes deprescribing unnecessary medications and can impact workflow) and incentives. System factors can affect shared decision-making.39

The deprescribing process (including, critically, the decision to deprescribe) is ideally shared by patients and prescribers, and it is often comprised of steps such as taking a medication history, identifying medications that can be deprescribed, and withdrawing those medications.5 Our framework also accommodates non-shared decisions and actions (e.g., unintended interruptions or discontinuations, patient non-adherence, prescriber unilateral decisions). The deprescribing process also addresses technology that implicitly encourages prescribing, but not deprescribing. That is, most clinicians in developed countries use an electronic order entry “prescribing system,” but there are not analogous “deprescribing systems.”

Effects and measures capture the results of deprescribing trials upon which researchers can focus, adapting the classic Donabedian framework (and similar to “monitoring” in the Bain et al. model of medication use).27, 40 Measures of Structure assess the fidelity of intervention uptake (e.g., whether an electronic health record change was implemented) while measures of Process assess the performance of the intervention. Both measures permit implementation assessment, a major research gap in deprescribing. Outcomes and Experiences are key measures in deprescribing trials as described in the model by Farrell et al., including both short-term (benefit, safety, and harm of deprescribing) and longer-term outcomes (quality of life, self-reported health, morbidity and mortality), particularly “patient important outcomes.”33 Finally, we include Cost as a key measure, for both health systems and patients. Intervention cost and cost-effectiveness must be evaluated to understand the likelihood of adoption and sustainability.6

Lastly, the eventual findings resulting from studies based upon the model will be limited in impact unless the successful approaches identified are broadly taken up across health care systems. However, there are major gaps in dissemination of deprescribing science findings and implementation of effective interventions.34 To address these limitations, the conceptual model includes Dissemination as a key component.

Discussion

We developed a new conceptual framework that can help organize the deprescribing literature and identify opportunities to expand it by fostering deprescribing research. We believe its unifying design fills a critical gap in the field by providing guidance about how to understand and evaluate factors related to deprescribing. In turn, as knowledge is gained and interventions are developed, the safety and quality of prescribing will improve.

The intentionally broad design of our conceptual framework lends itself to be adapted by the end-user to best meet their needs at various junctions in the research pipeline. For example, specific patient factors may vary depending on the population (e.g., socio-economic status).. Similarly, the system factors will differ based upon where the care is delivered (e.g., community-dwelling vs. long-term care facility) and payment mechanisms. Because this novel framework is generalizable to all healthcare settings, it can facilitate coordination of research on interventions across sites of care.

As the field of deprescribing expands, the ability to compare findings across studies is essential. A prerequisite to this is standardization of important outcomes and measurement of them. Our framework enables mapping of outcomes and metrics, which include short-term metrics (e.g., number of medications per patient) and long-term metrics (e.g., hospitalizations, mortality), as well as system-generated and patient-reported outcomes. A standard ontology of metrics will also enable planning of comparative effectiveness studies, an area with limited evidence in the deprescribing literature. Similarly, it will allow for consistent reporting of trial results.

Finally, it is critical that any newly developed interventions be successfully implemented and adopted by the end-user. Without this crucial component, eventual findings will be limited in impact. The field of implementation science is growing, but de-implementation, to which deprescribing belongs, has lagged.11 To that end, adoption of novel interventions will need to capitalize on the balance between implementation (i.e., integration of new tools) and de-implementation (e.g., unlearning). Our framework might also promote dissemination of beneficial practices and discontinuation of harmful behaviors in a variety of clinical settings which vary in system factors and available resources.

In sum, this novel conceptual framework is intended to help organize and identify opportunities to study multiple aspects of deprescribing research, including development of conceptually sound and well-targeted deprescribing interventions and dissemination of successful approaches to foster appropriate use of medication. Through testing and refinement, this more comprehensive conceptual framework has the potential to advance deprescribing research by organizing the existing evidence, identifying evidence gaps, and categorizing deprescribing interventions and the settings in which they are applied.

Acknowledgements

Funding:

Dr. Linsky was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (CDA12–166). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dr. Linder is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R21AG057400, R21AG057396, R21AG057383), National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21AG057395), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS024930, R01HS026506), The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, The Peterson Center on Healthcare, and a contract from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHSP2332015000201).

Dr. Friedberg received no financial support specifically for the current paper. Since 2016, Dr. Friedberg has received financial support for research from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, American Board of Medical Specialties Research and Education Foundation, American Medical Association, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Commonwealth Fund, Milbank Memorial Fund, National Institute on Aging, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Since 2016, Dr. Friedberg has received payments from Consumer Reports for consulting services, from Wolters Kluwer for co-authorship of an UpToDate article about hospital quality measurement, and from Harvard Medical School for tutoring medical students in health policy. Since 2016, Dr. Friedberg has received support to attend meetings from the American Medical Association, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Friedberg also has a clinical practice in primary care at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and thus receives payment for clinical services, via the Brigham and Women’s Physician Organization, from dozens of commercial health plans and government payers, including but not limited to Medicare, Medicaid, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts, Tufts Health Plan, and Harvard Pilgrim Health Plan, which are the most prevalent payers in Massachusetts.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: None

Conflict of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics (US). Health, United States, 2016: with chartbook on long-term trends in health 2017. Report No.: 2017–1232. [PubMed]

- 2.Akazawa M, Imai H, Igarashi A, Tsutani K. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8: 146–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, Mandl KD. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19: 901–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62: 2261–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78: 738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm 2013;66: 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30: 285–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Kouladjian L, Hilmer SN. Deprescribing trials: methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomes. Clin Geriatr Med 2012;28: 237–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;82: 583–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175: 827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronquillo C, Day J, Warmoth K, Britten N, Stein Ken, Lang I. An Implementation Science Perspective on Deprescribing. Public Policy Aging Rep 2018;28: 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd A, Jansen J, Colvin J, McLachlan AJ. The deprescribing rainbow: a conceptual framework highlighting the importance of patient context when stopping medication in older people. BMC Geriatr 2018;18: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30: 793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell B, Richardson L, Raman-Wilms L, de Launay D, Alsabbagh MW, Conklin J. Self-efficacy for deprescribing: a survey for health care professionals using evidence-based deprescribing guidelines. Res Social Adm Pharm 2018;14: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinicaltrials.gov Search for “Deprescribing” Accessed October 7, 2018.

- 16.Page A, Clifford R, Potter K, Etherton-Beer C. A concept analysis of deprescribing medications in older people. J Pharm Pract Res 2018;48: 132–148. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;80: 1254–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouellet GM, Ouellet JA, Tinetti ME. Principle of rational prescribing and deprescribing in older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2018: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Holmes H Rational prescribing for patients with a reduced life expectancy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;85: 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson W, Lundby C, Graabaek T, et al. Tools for Deprescribing in Frail Older Persons and Those with Limited Life Expectancy: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67: 172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes HM, Hayley DC, Alexander GC, Sachs GA. Reconsidering medication appropriateness for patients late in life. Arch Intern Med 2006;166: 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molist Brunet N, Espaulella Panicot J, Sevilla-Sánchez D, et al. A patient-centered prescription model assessing the appropriateness of chronic drug therapy in older patients at the end of life. Eur Geriatr Med 2015;6: 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott I, Anderson K, Freeman C. Review of structured guides for deprescribing. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2017;24: 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangin D, Bahat G, Golomb BA, et al. International Group for Reducing Inappropriate Medication Use & Polypharmacy (IGRIMUP): Position Statement and 10 Recommendations for Action. Drugs Aging 2018;35: 575–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med 2010;170: 1648–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63: 2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bain KT, Holmes HM, Beers MH, Maio V, Handler SM, Pauker SG. Discontinuing medications: A novel approach for revising the prescribing stage of the medication-use process. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56: 1946–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Pillans PI, Mitchell CA. Deciding when to stop: towards evidence-based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2013;18: 121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linsky A, Simon SR, Bokhour B. Patient perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98: 220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ open 2014;4: e006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linsky A, Simon SR, Marcello TB, Bokhour B. Clinical provider perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Am J Manag Care 2015;21: 277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrell B, Conklin J, Dolovich L, et al. Deprescribing guidelines: An international symposium on development, implementation, research and health professional education. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019;15: 780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrell B, Pottie K, Rojas-Fernandez CH, Bjerre LM, Thompson W, Welch V. Methodology for developing deprescribing guidelines: using evidence and GRADE to guide recommendations for deprescribing. PLoS One 2016;11: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson W, Reeve E, Moriarty F, et al. Deprescribing: future directions for research. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019;15: 801–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafar S, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology 2013;27: 80–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linsky A, Meterko M, Stolzmann K, Simon SR. Supporting medication discontinuation: provider preferences for interventions to facilitate deprescribing. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17: 447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.André M, Borgquist L, Foldevi M, Mölstad S. Asking for ‘rules of thumb’: a way to discover tacit knowledge in general practice. Fam Pract 2002;19: 617–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315: 562–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedberg MW, Van Busum K, Wexler R, Bowen M, Schneider EC. A demonstration of shared decision making in primary care highlights barriers to adoption and potential remedies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32: 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donabedian A The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260: 1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]