Abstract

Although several potassium currents have been reported to play a role in arterial smooth muscle (ASM), we find that one of the largest contributors to membrane conductance in both conduit and resistance ASMs has been inadvertently overlooked. Here we show that IKNa, a sodium-activated potassium current, contributes a major portion of macroscopic outward current in a critical physiological voltage range that determines intrinsic cell excitability; IKNa is the largest contributor to ASM cell resting conductance. A genetic knock-out mouse strain lacking KNa channels (KCNT1 & KCNT2) shows only a modest hypertensive phenotype. However, acute administration of vasoconstrictive agents such as angiotensin II (Ang II) and phenylephrine results in an abnormally large increase in blood pressure in the knockout animals. In wild-type animals Ang II acting through Gαq protein-coupled receptors down-regulates IKNa which increases the excitability of the ASMs. The complete genetic removal of IKNa in KO mice makes the mutant animal more vulnerable to vasoconstrictive agents, thus producing a paroxysmal-hypertensive phenotype. This may result from the lowering of cell resting K+ conductance allowing the cells to depolarize more readily to a variety of excitable stimuli. Thus, the sodium-activated potassium current may serve to moderate blood pressure in instances of heightened stress. IKNa may represent a new therapeutic target for hypertension and stroke.

Keywords: vascular smooth muscle, KNa1.1, KNa1.2, SLO2.1, SLO2.2, Slick, Slack, SLO1, Angiotensin II, potassium channel, hypertension, blood pressure, artery

INTRODUCTION

High conductance K+ channels activated by Na+ (KNa channels) were originally observed in inside-out membrane patches pulled from guinea pig cardiomyocytes (Kameyama et al., 1984). These channels resembled high conductance BK (Ca2+-activated) K+ channels, but were insensitive to Ca2+ and instead required high concentrations of intracellular Na+ to be active. Because of the high intracellular Na+ needed to activate these channels in detached inside-out patches it was originally thought that they were principally active under ischemic and low oxygen conditions, where they could counter toxicity when an increase in [Na+]i resulted from the inhibition of the Na+/K+-ATPase. However, more recent experiments have shown that these channels are present in many cell types and are commonly active and prominent under normal physiological conditions (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012). We found that these channels did not require very high concentrations of Na+ in the bulk cytoplasm; instead, persistent Na+ leak currents present in many cell types raise the Na+ concentration sufficiently in the intracellular submembrane region [sometimes referred to as the ”fuzzy space” (Barry, 2006; Blaustein and Wier, 2007; Verdonck et al., 2004)]. Thus, to visualize IKNa we found that any treatment that eliminates the persistent inward sodium leak current will also reduce IKNa as a secondary consequence of lowering [Na+]i in the submembrane region. We demonstrated this in neurons in several ways. We used blockers of the sodium leak current such as tetrodotoxin or riluzole that removed the sodium leak current which was rapidly followed by the removal of IKNa. We also replaced external Na+ with an impermeant ion (or with lithium ion which is permeable to sodium channels but ineffective in activating KNa channels) and achieved similar results. Although these experiments removed both the fast component of the sodium current as well as the INa leak, other experiments in neurons showed that it was the persistent sodium leak current and not the fast transient sodium current that was the critical factor (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012). These experiments also showed why IKNa was a non-inactivating K+ current resembling the “delayed rectifier” of (Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952), but active over a wider voltage range. These findings are not limited to neurons. In a recent publication (Ferreira et al., 2018) we found that IKNa is also present in uterine smooth muscle cells contributing to uterine smooth muscle resting membrane potential.

We now present evidence that IKNa is also present in arterial smooth muscle (ASM), where it can also be eliminated and analyzed as the subtracted component after removal of external Na+ ion. In arterial smooth muscle it is possible that the pathway of sodium leak entry that activates IKNa is through non-voltage dependent Na+ channels such as NALCN which we show are present in ASM. We also show that IKNa is the largest component of potassium current at the ASM cell resting potential which is critical in determining the intrinsic excitability of the ASM cell. The magnitude of resting cell potassium conductance is important in limiting cell depolarization when the cell is subjected to excitable stimuli such as excitatory junction potentials (EJPs), circulating neuromodulators, or activation of Ca2+-sensitive nonspecific cation channels (TRPM4) by changes in cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics (Gonzales and Earley, 2013). Such stimuli can depolarize the cell to a level which activates voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) resulting in increased arterial tone and higher blood pressure. Thus, it can be predicted that a mutation that lowers the potassium conductance of the ASM cell membrane at rest would make the cell more likely to respond to excitable stimuli, producing higher blood pressure. This is exactly what we find happens in a genetic knock-out of the IKNa current. The biophysical phenotype of the IKNa knock-out is a lowering of resting cell K+ conductance, and the physiological phenotype is an abnormally large increase in blood pressure when the knockout animals are challenged with vasoconstrictors. Hence, we show that stimulating the IKNa knock-out animals with a vasoconstrictor (e.g. phenylephrine or angiotensin II) produces a much larger increase in blood pressure than in wild-type. Thus, the sodium-activated potassium current may serve to moderate blood pressure rise in instances where the sympathetic nervous system is in a heightened state. Indeed, it is plausible that IKNa opposes arterial smooth muscle depolarization in general with no specific relationship to sympathetic nervous system function.

METHODS

Animal care

Animals were handled and housed according to the National Institutes of Health Committee on Laboratory Animal Resources guidelines. Mice used were the C57BL/6J strain (The Jackson Laboratory); rats were Sprague-Dawley CD (Charles River). All experimental protocols (protocol #20160084) were approved by the Washington University in St Louis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide exposure, followed by cervical dislocation. Anesthesia was not used and every effort was made to minimize pain and discomfort.

KNa channel KO animals

KCNT1 & 2 gene KO mice (which encode IKNa channels and have the following names: Slo2.2; KNa1.1; Slack, and Slo2.1; KNa1.2; Slick, respectively) were synthesized by Xiaoming Xia. Details of their generation and validation were previously published (Martinez-Espinosa et al., 2015).

Acute arterial smooth muscle cell dissociation

The smooth muscle cell isolation procedure was adapted slightly from (Lorca et al., 2018). Mouse or rat aortas (25–30 days of age, from both sexes) were removed, washed in HEPES-buffered saline [HBS], stripped of adventitial fat, and incubated in 1 mg/mL collagenase for 10 min at 37°C. The adventitial layer was removed with forceps, the tissue was cut into 1–2 mm rings, digested in 1.5 mg/mL papain for 25 min, then a combination of 1 mg/mL collagenase and 0.5 mg/mL elastase for 3–5 min. The digested tissue was triturated in a small volume of HBS into a single-cell suspension using pipet tips, and plated on 35 mm dishes at 4°C until use the same day. Mouse aortas were processed identically, except that the last digestion step (collagenase plus elastase) was omitted. Rat femoral arteries were cut into 2–4 mm pieces without peeling of adventitia, incubated in the collagenase plus elastase solution at 37°C for 20 min, then triturated as above. Cells maintained in culture were processed identically to fresh cells, except that after 1 hr the HBS was replaced with DMEM and 10% fetal bovine serum, and cells were incubated at 37°C. All enzymes were purchased from Worthington labs (Lakewood, NJ).

Electrophysiology and Data Analysis

Voltage-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices). Recordings were filtered at 2 kHz with the internal filter of the amplifier and digitized at 10 kHz using a Digidata 1322A digitizer (Molecular Devices). Recording pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass with tip resistances of 3–5 MΩ after filling with standard pipette solution containing (in mM): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, pH 7.3 with KOH (see Figure Legends for exceptions). Standard bath solutions contained (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3 with NaOH. 0 Na+ external solutions replaced all NaCl with choline·Cl, NMDG·Cl or LiCl as indicated. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was prepared daily from a 3 mM stock solution (in DMSO). Angiotensin II (Ang II) was freshly prepared from a 20 mM stock solution (in ddH2O). All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Single-channel data were analyzed with the threshold-based single-channel search function of Clampfit 10.6 (Molecular Devices). Statistical analysis and curve fitting were performed with OriginPro 7.5 (OriginLab Corporation). Mean values are presented as mean±SD. For comparison of results between two groups, paired Student’s t tests were used for the same procedures before and after applied treatments.

KNa channel KO animals

Details of generation and validation of KCNT1 & 2 gene KO mice (which encode IKNa channels which have the following names: Slo2.2; KNa1.1; Slack, and Slo2.1; KNa1.2; Slick, respectively) were previously published (Martinez-Espinosa et al., 2015).

RT-PCR

Total RNA from rat aorta was prepared using Qiagen’s RNeasy Plus Mini Kit. First strand synthesis was performed on 1.2 μg of the total RNA using Invitrogen’s SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase and random hexamers. KAPA Biosystem’s KAPA 2G Fast Ready Mix was used to perform PCR on 1 μl of the reverse transcriptase reaction using the following primer pairs specific to the rat coding sequences for Slick, Slack, NALCN, and the control Beta Actin (all are described 5’ to 3’): KCNT2 (Slick) Upper TGCCTCCCAGGTACAGATTCCGTGAT; KCNT2 (Slick) Lower TTGTTTCAAATAGACTTATCAATGCCACCGAGA; KCNT1 (Slack) Upper GTCTTGGAGATGATCAACACAC-TGCCCTTC; KCNT1 (Slack) Lower TTTCGGGCTTGAGAATCTGGACATAG; NALCN Upper GCATGCACCC-ACTTTACAGATCGCTGAA; NALCN Lower AAGATGCCGTTACAGTCTTCCCTTCTGATAATG; Beta Actin Upper ATGGAGAAGATCTGGCACCACACCTTCTAC; Beta Actin Lower TCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCTGCTGGAAG.

Arterial blood pressure measurement:

Arterial blood pressure and heart rate were measured in 3 month-old SLO2 KO and WT mice (males and females) under 1.5% v/v inhaled isoflurane anesthesia and while maintained at 37°C using heating pad and a rectal thermometer. To place the arterial pressure transducer, a midline incision was performed in the neck region; the thymus, muscle and connective tissue were dissected away to isolate the right common carotid artery. After tying it distally and clamping it proximally, an incision was made in the carotid artery through which a Millar pressure transducer (model SPR-671, Houston, TX) was introduced, the clamp was removed and the transducer advanced to the ascending aorta. Once instrumentation was complete, arterial blood pressure (systolic, diastolic and mean) and heart rate were recorded via the PowerLab® data acquisition system (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Data were analyzed using LabChart® 7 for MAC software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO).

BP determination after acute intravenous Ang II injection:

To assess the blood pressure response to acute administration of vasoconstrictive agents, after placing the Millar pressure transducer as above, dissection was performed to visualize the left internal jugular (IJ) vein. Once identified, a small incision was made and PE-10 tubing was introduced and kept in place with a 6–0 silk suture. While measuring arterial blood pressure, 50 μl normal saline (NS) was injected via the IJ line as a bolus injection (1–2 sec). After 5 min, 1 μg/kg Ang II (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a ~10 μl volume was injected in the IJ line and flushed with 40 μl NS. When blood pressure returned to baseline (2–3 min), the line was washed with 50 μl NS for 3 min. 100 μg/kg phenylephrine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a ~10 μl volume were then injected followed by 40 μl NS (1–2 sec). Blood pressure was monitored until it returned to baseline (2–3 min) and the mouse was sacrificed.

RESULTS

Two distinct classes of high conductance K+ channels are present in ASM cells.

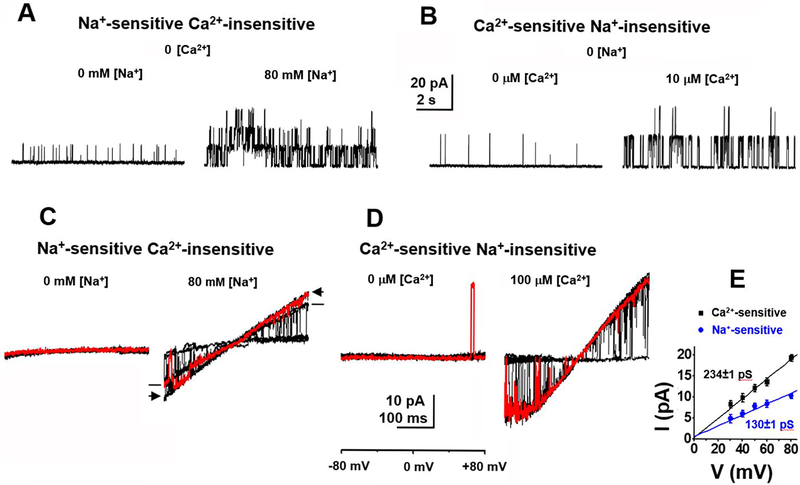

Two classes of high conductance K+ channels are seen in inside-out patches pulled from acutely isolated rat ASM cells. These two classes are distinct with respect to their different ion dependence and their different single channel conductance. Sodium-activated potassium (KNa) channels are activated by exposing the cytoplasmic surface of the patch to mM concentrations of Na+ (Fig. 1A and C), and have a single channel conductance of approximately 130 pS in 140 mM symmetrical K+ (Fig. 1E). These single channel KNa currents are most abundant in freshly isolated ASM cells, and carry a major portion of macroscopic outward current in these cells. Calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channels, on the other hand, have been well characterized in these cells (Eichhorn and Dobrev, 2007; Hu and Zhang, 2012; Ledoux et al., 2006; Toro and Stefani, 1987) and are activated by exposing the cytoplasmic surface of the patch to μM intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 1B and D). KCa channels have a larger single channel conductance [above 200 pS under similar (140 mM symmetrical K+) conditions] (Fig. 1E). The single channel currents with Ca2+-sensitivity are known to be carried by channels of the SLO1 BK channel subfamily (KCa1.1).

Fig. 1. Two distinct classes of high conductance K+ channels in both mouse (A, B & E) and rat (C & D) ASM cells.

(A) Na+-sensitive single channel currents recorded from an inside-out patch excised from an acutely isolated mouse aortal cell. Currents were recorded at +80 mV in 140 mM symmetrical K+o/K+i with 0 (left) or 80 mM (right) [Na+]in. The NPo increased from 0.01 to 0.09 when [Na+]in was changed from 0 to 80 mM. The amplitude of the main opening level of this Na+-sensitive current was 10.3±1.7 pA (n=8). (B) Ca2+-sensitive single channel currents recorded at +80 mV in 140 mM symmetrical K+o/K+i with 0 (left) or 10 μM (right) [Ca2+]in. The NPo increased from 0.02 to 0.17 after perfusing in 10 μM [Ca2+]in. The amplitude of the main opening level of the Ca2+-sensitive current was 19.4±2.3 pA (n=8). (C) Na+-sensitive single channel currents evoked by voltage ramps from −80 to +80 mV recorded from an inside-out patch excised from an acutely isolated rat aortic muscle cell. The patch was perfused in 140 mM symmetrical K+o/K+i in the absence of [Ca2+]in with 0 (left) or 80 mM (right) [Na+]in. Ten current traces are superimposed with one highlighted in red for each condition. Note that all openings including subconductance states are lacking in the absence of [Na+]in. (D) Ca2+-sensitive currents evoked by voltage ramps from −80 to +80 mV recorded from an inside-out patch excised from an acutely isolated rat aortic muscle cell. The patch was perfused in 140 mM symmetrical K+o/K+i in the absence of [Na+]in with 0 (left) or 100 μM (right) [Ca2+]in. Ten current traces are superimposed with one highlighted in red for each condition. (E) Mean single channel current-voltage relationships of channels sensitive to either intracellular Na+ (blue circles) or Ca2+ (black squares) averaged from 4 to 8 patches excised from acutely isolated mouse ASM cells. The single channel conductance of Na+-sensitive and Ca2+-sensitive channels is 130±1.2 pS and 234±1.4 pS, respectively.

KNa channels were first characterized in native guinea pig cardiomyocytes (Kameyama et al., 1984), and subsequently found to be carried by the SLO2 K+ channel subfamily (KNa1), by cloning and heterologous expression of SLO2 cDNAs in Xenopus oocytes (Yuan et al., 2003). While both KNa and KCa channel types can be seen to open over a wide voltage range under experimental conditions where symmetrical K+ ion is present (Fig. 1), we will show that under physiological conditions IKNa contributes the larger component of outward current in the negative voltage range.

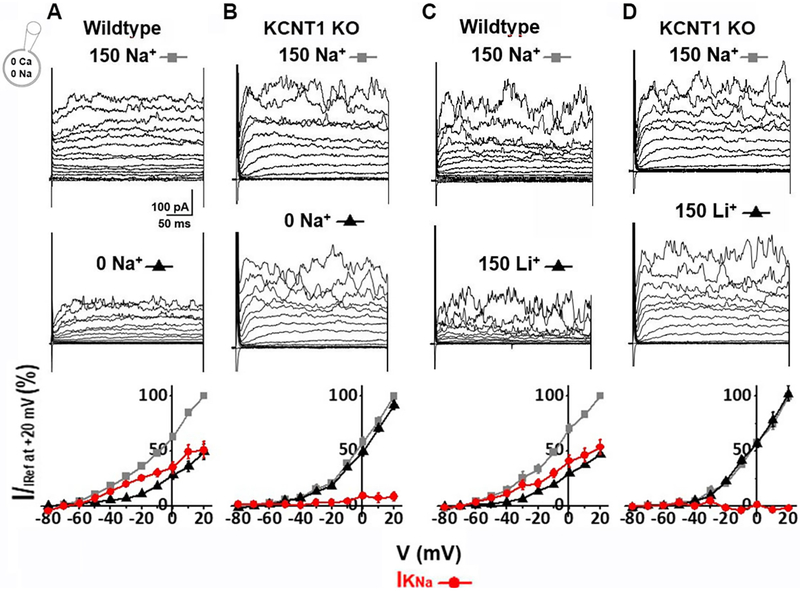

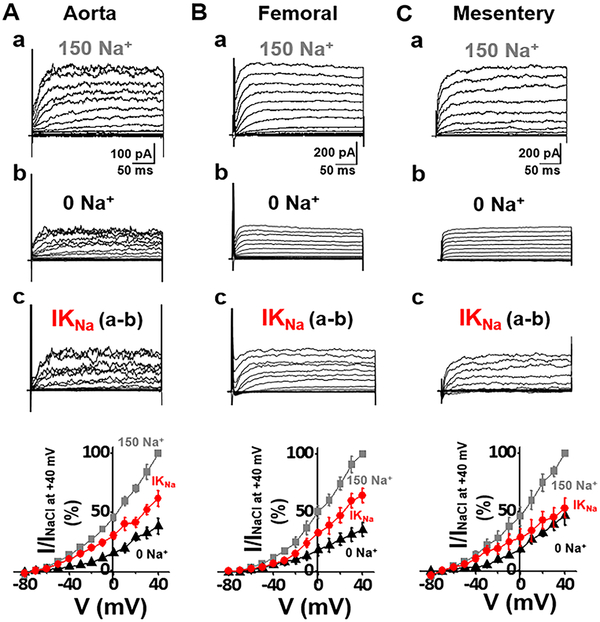

Macroscopic Na+-dependent K+ currents (IKNa).

When originally observed, it was thought that sodium-activated potassium currents represented a reserve conductance to be called upon when cells were under hypoxic or ischemic conditions (Kameyama et al., 1984). However, we showed that IKNa was a large component of outward current active under normal physiological conditions (Budelli et al., 2009). Previous studies of the macroscopic IKNa current in mammalian neurons identified it as a time-dependent, non-inactivating outward current resembling a voltage-dependent delayed rectifier K+ current (Budelli et al., 2009). However, IKNa has lower voltage sensitivity and is open over a wider voltage range than the classic delayed rectifier. We now show that this current is present in ASMs. To illustrate this, as we had done in neurons (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012), we removed external sodium ion and replaced it with an impermeant ion (Fig 2A). This treatment removed more than 50% of the outward current. IKNa is reduced when extracellular Na+ is removed because IKNa depends on a small but persistent sodium leak current (INaP) into the cell (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012). Importantly, there was no Na+ in the intracellular pipette solution which shows the effectiveness of Na+ influx for activation of IKNa (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012). In neurons, INaP is carried by reopenings of voltage-gated sodium channels. Other cell types such as ASMs have non-voltage dependent Na+ channels which carry INaP, i.e. NALCN (Reinl et al., 2015; Reinl et al., 2018) and ENaCs (Smith and Brock, 1983; Touyz and Schiffrin, 1999). A small but persistent sodium leak into the cell appears to maintain [Na+] in the submembrane space in the vicinity of KNa channels at a higher concentration than in the bulk cytoplasm (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012). We observed IKNa in both conduit (aorta, Fig. 4A) and resistance (femoral and mesentery, Fig. 4B&C) arteries. The macroscopic KNa current itself can be seen as the subtractive component which is the difference between the current before and after the removal of external Na+. In both types of ASM cells IKNa represented more than half of the outward current. Significantly, macroscopic IKNa is absent in the mouse knock-out line of the KCNT1 gene which encodes the SLO2.2 (Slack) KNa channel (Yuan et al., 2003) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. IKNa is a major outward current in wild-type mouse ASM cells, but is absent in the KCNT1 knock-out.

(A) Whole cell currents recorded from an acutely isolated mouse aortic smooth muscle cell. Currents were evoked from a holding potential of −70 mV by steps from −80 to +60 mV in 10 mV increments. Pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. The control currents (top) were recorded in bath solution containing (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH=7.3. Replacing extracellular Na+ with choline (middle) markedly reduced the magnitude of outward currents. The IKNa portion of current was isolated by subtraction of the current recorded in 0 [Na+]out from the control current. The bottom panel shows the normalized I–V relationships of above currents measured during the last 50 ms of each voltage step. At −20 mV, the IKNa portion of current was 70.0±2.08% of total outward current (n=5). (B) Whole cell currents were recorded under conditions similar to A from an acutely isolated KCNT1 knock-out (KO) mouse ASM cell. At −20 mV, the IKNa portion of current was a statistically insignificant portion of total outward current (n=5), indicating that IKNa is absent in the KO. (C) Substitution of LiCl for extracellular NaCl produced a similar reduction of outward current as in A from wild-type. At −20 mV, the IKNa portion of current was 60.1±3.78% of total outward current (n=5). (D) Substitution of LiCl for extracellular NaCl failed to reduce outward current from KCNT1 KO cells as in B. At −20 mV, the total outward current in the presence or absence of Li+ was statistically indistinguishable which, as in B, suggests the absence of IKNa in KCNT1 KO cells.

Fig. 4. IKNa (SLO2) in both conduit (aorta) and resistance (femoral and mesentery) rat ASM cells.

(A) Whole cell currents recorded from an acutely isolated rat aortic smooth muscle cell. Recording protocols and conditions are described in Fig. 2 legend. The control currents (top) were recorded in bath solution containing 150 mM Na+. Replacing extracellular Na+ with choline (0 Na+) markedly reduced the magnitude of outward currents. The IKNa portion of current (bottom) was isolated by subtraction of the current recorded in 0 [Na+]out from the control current. The bottom panel shows the normalized I–V relationships of above currents measured during the last 50 ms of each voltage step. At −20 mV, the IKNa portion of total outward current was 72.6±2.42% (n=10). (B,C) Whole cell currents of an acutely isolated rat femoral or mesentery smooth muscle cell recorded under conditions similar to A. At −20 mV, the IKNa portion of current was 60.3±4.59% of total outward current in femoral (n=5), or 66.7±4.36% of total outward current in mesentery (n=7). IKNa was observed to contribute a large percentage (>50%) of outward current in both conduit and resistance arteries, and in both mice and rats.

In addition to the removal of external Na+, macroscopic Na+-dependent K+ currents can also be revealed in wild-type ASM cells by replacing the external Na+ with Li+ (Fig. 2C). Li+ is carried by most sodium channels but poorly substitutes for Na+ in activating KNa channels (Kaczmarek, 2013). Thus, in mouse aortal cells when extracellular Na+ is replaced with Li+, IKNa is also removed (Fig. 2C). Again, this treatment has no effect on the amplitude of outward currents in cells from the KCNT1 knock-out mouse strain (Fig. 2D). Additionally as can be noted in the graphical plots of the currents, IKNa is active even at negative voltages thought to be ASM cell resting potentials (England et al., 1993) (Fig. 2A and C, bottom panels). IKNa is the largest component of outward current at voltages more negative than 0 mV (Fig. 2A and C, red plotted data). Note that even though neither intracellular nor extracellular Ca2+ is present in these recordings, further analyses at basal levels of Ca2+ both inside and outside the cell reach the same conclusion regarding the relative contribution of IKNa (Fig.3).

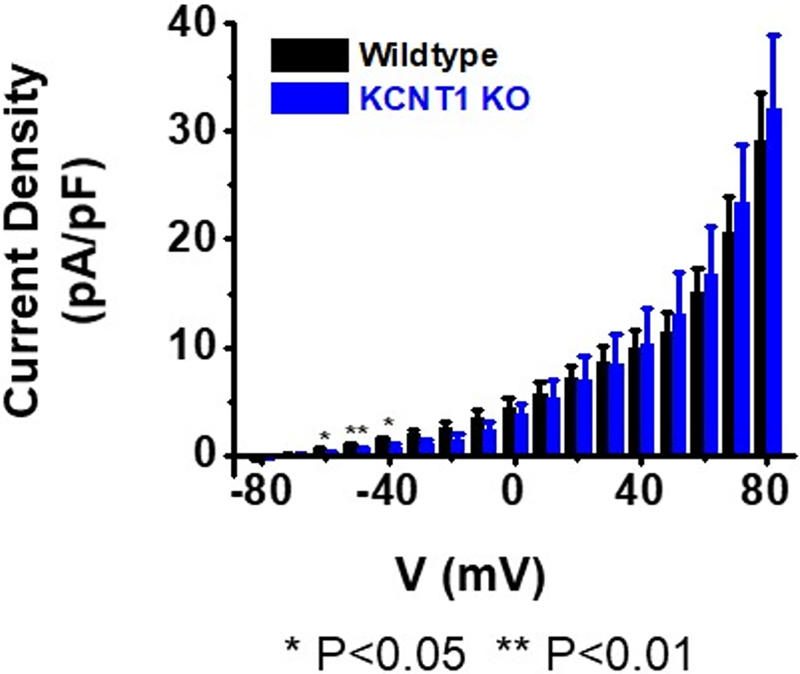

Compensatory up-regulation of K+ channels in the KCNT1 knock-out strain.

One notable feature seen in the analysis of the KCNT1 knock-out line was that, although the KNa channel was absent, the amplitude of the total outward current present in the cells seemed to be as large as in wild-type cells. To explore this further we measured the density of the outward currents normalized to cell capacitance over a range of voltages and compared these measurements between wild-type and KCNT1 knock-out ASM cells. The results of this comparison are presented in Fig. 5 which suggests that there is a compensatory up-regulation of other outward currents in the KCNT1 knock-out cells. This compensatory up-regulation is notable at positive voltages where there are no significant statistical differences in outward current density between wild-type cells and cells of the knock-out line. However, compensatory K+ currents are not present in the knock-out at or near the critical membrane resting potential (see below). We have not yet determined the identity of the channels carrying the compensatory up-regulated outward current in cells of the knock-out strain. At the highest voltages some of these channels may be SLO1 KCa channels. However, voltage-gated K+ channels increase their expression relative to other channel types when ASM cells are maintained in cell culture (Cidad et al., 2010; Tang and Wang, 2001). This increase in voltage dependent K+ current in wild-type ASM cells as a percentage of total current when ASMs are maintained in cell culture makes IKNa less prominent in long-term cell culture. This is also true in wild-type animals after six months of age. However, in cells of the KCNT1 knock-out strain, compensatory currents at negative cell membrane voltage, at and near the critical cell membrane resting potential, are not present (Table 1). This significant reduction in the resting membrane K+ current relative to wild-type cells should increase the relative excitability of the mutant ASM cells. Nevertheless, an interesting point of speculation that can be surmised from Fig. 2 is that if it were not for compensatory up-regulation of other K+ currents in IKNa knock-out animals, the hypertensive phenotype might be more severe.

Fig. 5. Compensatory up-regulation of K+ channels in the KCNT1 knock-out strain except at negative resting potentials.

Density of outward current was measured between wild-type and KCNT1 knock-out ASM cells and normalized to cell capacitance over a voltage range of −80 mV to +80 mV. Recording solutions are described in Table 1 legend. Although IKNa was absent in the KCNT1 knock-out line, the amplitude of the total outward current in the cells appeared to be as large as wild-type (P=0.011 at +80 mV). However, at the negative voltages of −60, −50, and −40 mV, the current density from KO cells is significantly less than that of wild-type. At −50 mV the current density for WT or KO cells respectively is 0.89±0.21 pA/pF (n=14), vs 0.43±0.22 pA/pF (n=10). More details of relative conductances at negative voltage values are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of slope conductance at −50 mV between wild-type and KCNT1 knock-out strain.

Whole cell currents were recorded from mouse aortic smooth muscle cells acutely isolated from either wild-type or KCNT1 knock-out strain in the presence or absence of Na+ or 1 μM Ang II. Normal saline bath solution containing (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH=7.3. Na+-free saline bath solution containing (in mM): 150 NMDG-Cl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH=7.3. Pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3 with estimated 200 nM free Ca2+. Currents were evoked from a holding potential of −70 mV by steps from −70 to −30 mV at 5 mV increments. The I-V curves in this range had slight outward rectification. The slope conductance was obtained by fitting a linear tangent at −50 mV for the data obtained from −70 mV to −30 mV, then normalized to cell capacitance. Statistical analysis was performed with OriginPro 7.5. Mean values are presented as mean±SD. Student’s t tests were used for comparison of results between two groups. For wild-type, the slope conductance is significantly reduced in the absence of Na+ or presence of 1 μM Ang II (n=5, P<0.0001). The KCNT1 knock-out strain has a significant reduction in the overall resting membrane current relative to WT (n=5, P<0.00001). However, the reduced slope conductance is unchanged in the absence of Na+ (n=5, P=0.88) or presence of 1 μM Ang II (n=5, P=0.99), which is consistent with the absence of IKNa in the KCNT1 KO. In 0 [Ca2+]i (in the presence of intracellular 5 mM EGTA), the slope conductance remained unchanged statistically. It was 85.4±6.41 pS/pF (n=3, P=0.15) for wild-type or 31.6±4.39 pS/pF (n=3, P=0.21) for KCNT1 KO, respectively. These data suggest that there is no significant contribution from a Ca-dependent resting conductance in these ASM cells. The absence of a contribution of BK channels in resting conductance is consistent with the low reported nPo of BK channels (<0.0001) at this voltage range with less than 1 μM intracellular Ca2+ (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002).

| Normal saline | Na+-free saline | +1 μM AngII | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 92.2±9.01 (ref) | 47.5±4.92*** | 47.9±3.61*** |

| KCNT1 KO | 35.0±5.97**** | 35.2±5.72**** | 31.3±5.21**** |

P<0.0001;

P<0.00001

Macroscopic IKNa is larger than IKCa in the physiological ranges of ASM voltage and basal [Ca2+].

We measured the relative amounts of IKNa and calcium-activated K+ currents, IKCa, in freshly isolated ASMs from wild-type rats with a defined concentration of intracellular Ca2+ to assay the relative amounts of IKNa vs IKCa at a fixed concentration of [Ca2+]i and Ca2+]o, at physiological voltages (Fig. 3). Prominent among IKCa present in ASM cells is the current carried by high conductance “BK” (also called “SLO1”) channels encoded by the KCNMA1 gene (Ledoux et al., 2006). An example of these (single channel) currents is shown in Fig. 1B. In these experiments IKNa vs IKCa current components were measured when the intracellular [Ca2+] was buffered at a physiological level (200 nM) and extracellular [Ca2+] was 2 mM. Under these conditions IKNa relative amplitude at negative voltages was similar to that shown in Fig. 2 where no Ca2+ was present, and still clearly greater than IKCa and all other outward currents combined. In fact, IKCa didn’t exceed IKNa until cell depolarization reached +60 mV and above (Fig. 3D). However, we could not factor in how high IKCa could rise at localized sites where higher [Ca2+]i is achieved via calcium sparks and sparklets (Amberg and Navedo, 2013). Nevertheless, under conditions of our experiments which approximate basal physiological conditions, IKNa was the greater current.

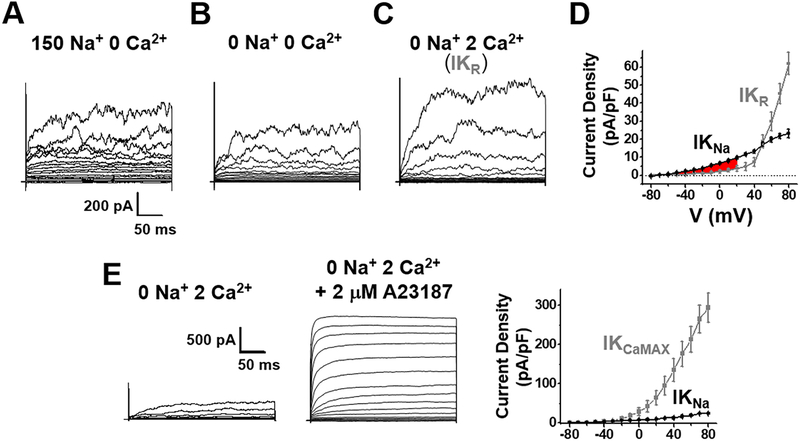

Fig. 3. IKNa is larger than IKCa at basal physiological conditions in rat aortic ASM cells.

Whole cell currents were recorded from acutely isolated rat ASM cells and evoked from a holding potential of −70 mV by steps from −80 to +80 mV at 10 mV increments. Pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3 (free Ca2+ estimated to be 200 nM). The currents in (A) were recorded in solution containing (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA,10 HEPES, pH=7.3. The currents in (B) were recorded in a solution where extracellular Na+ was replaced with choline. IKNa was determined by subtraction of the current recorded in B from A. (C) The total residual K+ current after the removal of IKNa (IKR) was recorded in a solution as in (B) but with 2 mM extracellular Ca2+. (D) Plots of the current density vs voltage relationships of IKNa (black circle) and IKR (grey circle). Overall, IKNa is a larger component than IKR from −60 mV to +60 mV, especially at physiologically relevant voltages (highlighted area in red). At −20 mV, the density of IKNa vs IKR was 3.99±0.34 pA/pF and 1.12±0.45 pA/pF, respectively; at +20 mV, the density of IKNa vs IKR was 9.74±0.69 pA/pF and 4.00±1.56 pA/pF (n=6, P<0.001), respectively. (E) A third set of experiments was performed to activate IKCa to its maximum amplitude by adding the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 at 2 μM to the extracellular medium in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+. Remarkably, these experiments showed that IKCa has a huge reserve potential relative to all other currents in the cell. At −20 mV, the density of IKNa vs IKCaMAX was 5.30±1.84 pA/pF and 9.50±2.48 pA/pF, respectively; at +20 mV, the density of IKNa and IKCaMAX was 10.4±3.88 pA/pF and 63.6±18.1 pA/pF (n=6, P<0.001), respectively. Thus, IKCaMAX represents a great repolarizing force normally held in reserve.

In a second set of experiments, however, we sought to activate IKCa to its maximum amplitude by artificially raising the intracellular concentration of Ca2+. This was accomplished by adding the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 to the extracellular medium in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+. Remarkably, these experiments showed that IKCa has a huge reserve potential relative to all other currents in the cell, and by far, represents the largest potential outward current in ASMs (Fig. 3E). The addition of A23187 more than quadrupled the amplitude of total outward current in ASM cells. Similar results with A23187 have been reported previously for rat aorta cells (Rusch et al., 1992). However, the activation of IKCa to a high level apparently only occurs when intracellular [Ca2+] raises to higher than basal levels, while under normal basal levels of [Ca2+]i IKNa dominates. This may be why several reports indicate that IKCa may not have a large influence on ASM cell resting excitability (Archer et al., 1996; Tammaro et al., 2004; Yuan, 1995).

Resting cell conductance is largely contributed by IKNa.

To measure the contribution of IKNa at negative cell resting potentials we measured the cell membrane current density and resting conductance under whole cell voltage clamp at negative resting potentials which bracketed reported cell membrane resting potentials (England et al., 1993; Pavenstadt et al., 1991). We found the resting cell current/voltage relation to be slightly outwardly rectifying within the voltage range of −70 to −30 mV. Table 1 reports the values of normalized slope conductance at −50 mV which is centered within this range. These experiments were undertaken in normal saline, and then in saline with extracellular Na+ removed in order to determine the contribution of IKNa to resting cell conductance. We also measured the cell membrane conductance in the KNa1.1 knock-out strain to verify the contribution of IKNa. Finally, we measured the change in resting cell conductance when Ang II was added to the extracellular medium, which showed that the vasoconstrictive agent significantly lowered resting membrane conductance, as has been previously observed (Chorvatova et al., 1996; Latchford and Ferguson, 2005; Quinn et al., 1987). Indeed, the lowered cell membrane conductance recorded after the addition of Ang II approached the lower conductance measured in cells of the KCNT1 knock-out mutant (Table 1).

Ang II modulates macroscopic IKNa.

It is well known that ASM cells express the angiotensin II type 1 receptor which signals through the Gαq protein-coupled receptors (GαqPCR) pathway to modulate arterial muscle tone [reviewed in (Mehta and Griendling, 2007; Touyz and Schiffrin, 2000)]. In previous studies we used a heterologous expression system to show that the activity of KNa channels is regulated by neuromodulators acting through the same signaling pathway (Kaczmarek, 2013; Santi et al., 2006). Furthermore, we showed that the regulation involves protein kinase C (PKC), as application of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), an activator of PKC (Santi et al., 2006), modulates the current. Here we show that the activity of IKNa in ASMs is also regulated through the GαqPCR pathway by application of Ang II to voltage clamped ASM cells and monitoring the response to whole cell currents. Fig. 6 shows that an outward current corresponding to IKNa in ASM cells is down-regulated by both the application of Ang II (Fig. 6A) and by the application of PMA (Fig. 6C). In contrast, application of Ang II to cells of the knock-out KCNT1 strain (Fig. 6B) or PMA to the knock-out strain (Fig. 6D) where IKNa is absent had no effect. As will be discussed, KNa channels encoded by SLO2 genes were previously shown in a heterologous expression system to be modulated by Ang II and other modulators which signal through the Gαq protein-coupled receptors (Santi et al., 2006). In that study, negative regulation via Gαq protein-coupled receptors was seen in either homomeric SLO2.1 (KNa1.2) channels, or in heteromultimers incorporating both SLO2.1 and SLO2.2 (KNa1.1) subunits. However negative regulation was not seen in homomeric SLO2.2 channels. In ASM cells we also see negative regulation. This suggests that the channels in ASM cells are either homomeric SLO2.1 (KNa1.2) channels, or heteromultimertic channels incorporating both SLO2.1 and SLO2.2 (KNa1.1) subunits [Note that both channels are expressed in ASM cells (Fig. 7) allowing for the possibility of heteromultimer formation]. Consistent with the possibility that the channels in ASM cells may be heteromultimers is the fact that KNa channels are deleted from the membrane both in SLO2.2 [KCNT1] KO ASM cells (Fig. 2), and in the SLO2.2+SLO2.1 KO (SLO2 KO) ASM cells (Fig. 8).

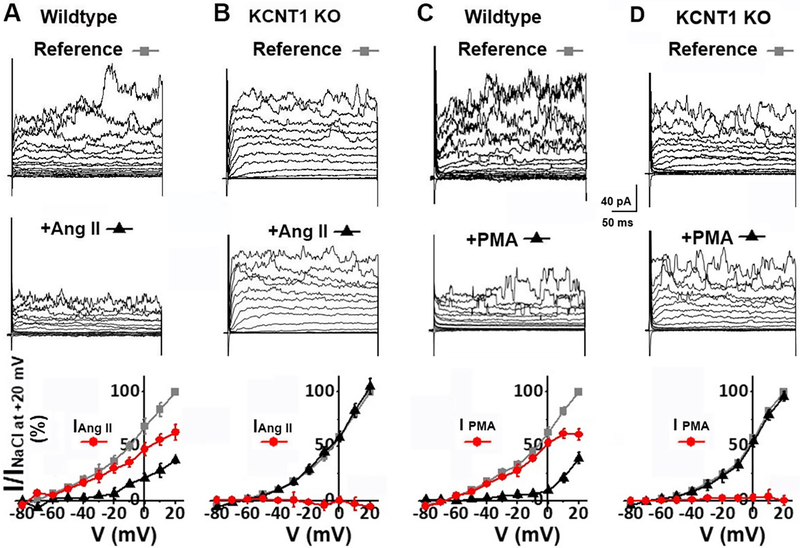

Fig. 6. Ang II and PMA negatively modulate IKNa in mouse wild-type ASM cells, but have no effect on KCNT1 knock-out currents.

(A) Whole cell currents recorded from a mouse aortic muscle cell in the absence (top) and presence (middle) of 300 nM Ang II. Currents were evoked from a holding potential of −70 mV by steps from −80 to +60 mV at 10 mV increments. The bottom panel plots the normalized current-voltage relationships of the outward current in the absence (grey square), and presence (black triangle) of Ang II; the Ang II sensitive current (subtraction of the current recorded in the presence of Ang II from the reference current) is plotted in red circles. 300 nM Ang II reduced the outward current by 81.2±4.92% (n=6, P<0.001) at −20 mV. (B) Whole cell currents of a KCNT1 KO aortic muscle cell in the absence (top) and presence (middle) of 300 nM Ang II. The bottom panel shows the normalized current-voltage relationships in the absence (grey square), and presence (black triangle) of Ang II. The subtraction protocol to show any current removed by Ang II is also plotted as red circles. 300 nM Ang II had no effect on outward current [at −20 mV, the outward current was 103.0±4.95% (n=5, P=0.92) of the reference current in the presence of Ang II]. (C) Whole cell outward current of a wild-type mouse aortic muscle cell in the absence (top) and presence (middle) of 100 nM PMA. 100 nM PMA reduced outward current by 83.5±5.79% (n=5, P=0.007) at −20 mV. (D) Whole cell currents of a KCNT1 KO aortic muscle cell were not inhibited after application of 100 nM PMA. The bottom panel shows the normalized current-voltage relationships in the absence (grey square) and presence (black triangle) of PMA; no PMA-sensitive current was detected [at −20 mV, the outward current was 93.2±2.42% (n=4, P=0.90) of the reference current in the presence of PMA]. Thus, PMA has no effect on KCNT1 KO cells. For experiments shown in this figure, the pipette solution contained (in mM): 110 KMES, 30 KCl, 20 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. Under these conditions the intracellular Ca2+ was buffered at approximately 200 nM which proved sufficient for the Ca2+-dependent GαqPCR signaling cascade to function. The bath solution contained (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH=7.3.

Fig. 7. Expression of KNa1.1 & KNa1.2 channels in rat aorta shown by RT-PCR.

Results are from RT-PCR experiments using primers specific for rat KNa1.1 (also called SLO2.2, Slack) or rat KNa1.2 (also called SLO2.1, Slick). The Leak Sodium Channel (NALCN) is also found in aorta; a β-actin control is also shown. A plus sign indicates the addition of reverse transcriptase to the reaction. A minus sign indicates a control in the absence of reverse transcriptase.

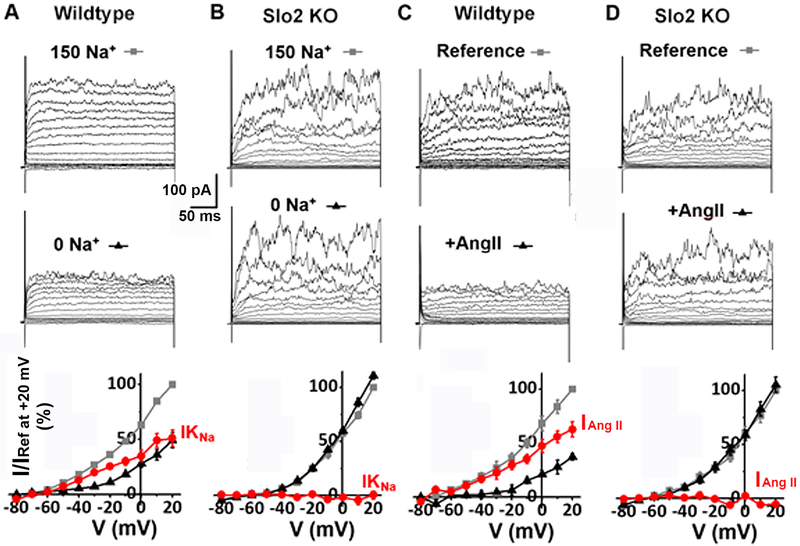

Fig. 8. Ang II modulation of IKNa in mouse aortal ASM cell is absent in the KCNT1-KCTN2 double knock-out cells.

(A) An example of whole cell currents recorded from an acutely isolated wild-type mouse ASM cell. Detailed experimental conditions and data analyses are provided in the legend to Fig. 2. Replacing extracellular Na+ with choline markedly reduced the magnitude of outward currents. IKNa (red circle) is greater than 50% of total outward current (the bottom panel is the same plot shown in Fig. 2A). (B) Whole cell currents were recorded under conditions same to A from an acutely isolated KCNT1 and KCNT2 knock-out (Slo2 KO) mouse ASM cell. The IKNa portion of current (red circle) was a statistically insignificant portion of total outward current (n=8), indicating that IKNa is absent in the Slo2 KO. At −20 mV, the outward current in the absence of Na+ (black triangle) was 100.6±3.00% (n=8, P=0.94) of the current in the presence of Na+ (grey square). (C) Another example of whole cell currents recorded from a mouse wild-type ASM cell in the absence and presence of 300 nM Ang II. Detailed experimental conditions and data analyses are provided in the legend to Fig. 6. The major outward currents are sensitive to Ang II (the bottom panel is the same plot shown in Fig. 6A). (D) Whole cell currents of a Slo2 KO ASM cell were not inhibited after application of 300 nM Ang II. The bottom panel shows the normalized current-voltage relationships in the absence (grey square) and presence (black triangle) of Ang II; no Ang II-sensitive current (red circle) was detected [at −20 mV, the outward current was 102.1±3.15% (n=5, P=0.84) of the reference current in the presence of Ang II]. Similarly, 100 nM PMA has no effect on Slo2 KO cells (n=5, P=0.88, data not shown). These results indicate that the Slo2 KO has the same electrophysiological phenotype as the single KCNT1 KO (Fig. 2 and Fig. 6), which is consistent with the hypothesis that the IKNa is a heteromultimer of subunits from both genes.

Genetic analysis shows that IKNa may moderate blood pressure in response to vasoconstrictive agents.

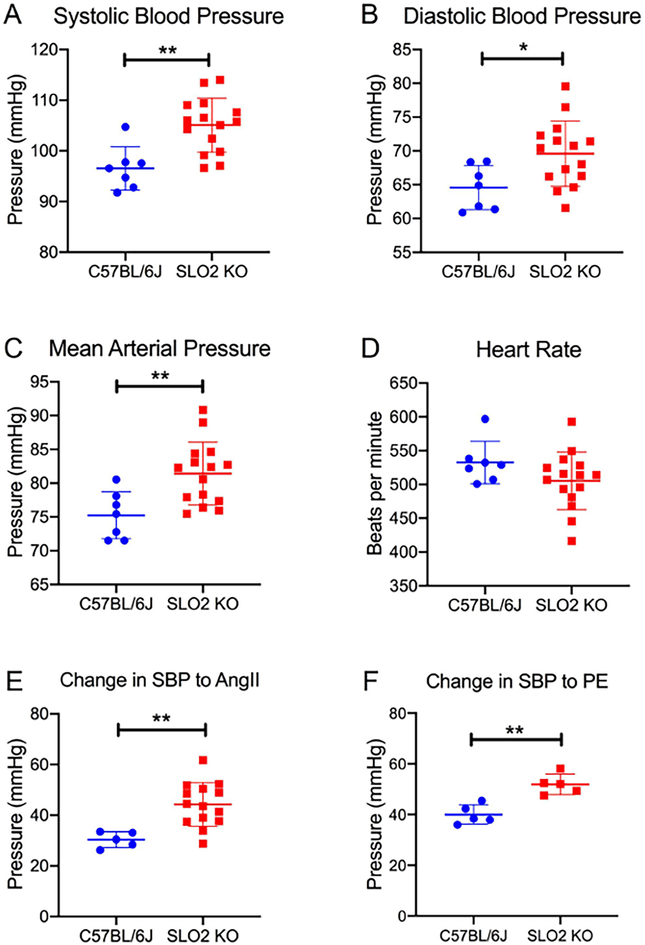

Genetic analysis using a mouse knock-out strain deleting KNa channels (KCNT1 & KCNT2) showed a modest hypertensive phenotype. However, treating the knockout animals with hypertensive agents such as phenylepherine and Ang II resulted in a larger increase in blood pressure relative to wild-type controls (Fig. 9). This might be expected because these agents both directly and indirectly increase arterial tone. Both Ang II and phenylephrine act directly on ASM cells because both AT1 receptors and alpha adrenergic receptors are present in ASM cells; when stimulated they evoke intracellular Ca2+ release resulting in increased tone. Indirectly, in an in vivo setting, they increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system which increases endogenous epinephrine and Ang II leading to a heightened blood pressure response in knock-out animals. Thus, the sodium-activated potassium current may serve to moderate blood pressure in all instances where stress produces an increase in vasopressor agents. Indeed the phenotype of the SLO2 KO mice resembled a paroxysmal hypersensitive phenotype and it might be interesting to investigate whether human genetic variation in KCNT1 and/or KCNT2 genes has any correlation with the human syndrome. The abnormal increase in the response to Ang II was especially interesting because it reflects the multiple roles that Ang II plays in blood pressure control.

Fig. 9. SLO2 KO mice are hypertensive and have a heightened response to vasoconstrictors.

Baseline systolic blood pressure (A), diastolic blood pressure (B), mean arterial pressure (C) and heart rate (D) of 3 month-old KCNT1 & KCNT2 double KO (SLO2 KO) and wild-type C57BL/6J mice. Systolic blood pressure was an average of 8.53±2.31 mmHg higher in SLO2 KO (105.1 mmHg) vs. WT mice (96.54 mmHg). Diastolic blood pressure was 5.01±2.02 mmHg greater in SLO2 KO (69.58 mmHg) vs. WT mice (64.57 mmHg), while mean arterial pressure was an average of 6.81±1.98 mmHg higher in SLO2 KO (81.42 mmHg) vs. WT mice (75.23 mmHg). Rise in systolic blood pressure (SBP) in response to acute intravenous administration of 1 μg/kg Ang II (E) or 100 μg/kg phenylephrine, PE (F) in SLO2 KO and wild-type mice. SBP increased by an average of 44.28 mmHg in SLO2 KO mice compared to 30.34 mmHg in WT mice in response to AngII. Phenylephrine resulted in an average SBP rise of 51.87 mmHg in SLO2 KO vs. 40.00 mmHg in WT mice. Data are presented as mean±SD. Student’s t-test was used to compare the 2 groups. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

These blood pressure measurements were undertaken using anesthesia. While general anesthesia with isoflurane exerts hemodynamic changes potentially leading to blood pressure and heart rate variability, it is important to note that the use of 1.5% v/v isoflurane in C57BL/6 mice (used in this study) has been shown to result in the most stable pressure and heart rate values that are comparable to those observed in conscious mice (Constantinides et al., 2011). Similar to its negative ionotropic effects at baseline, isoflurane anesthesia potentially alters the vasopressor response to AngII (Samain et al., 2002; Ullman et al., 2003) and phenylephrine (Hanouz et al., 1998). That said, as wild-type and SLO2 KO mice were treated under the same conditions, any differences in blood pressure responses between the two genotypes relate to the loss of SLO2 channels.

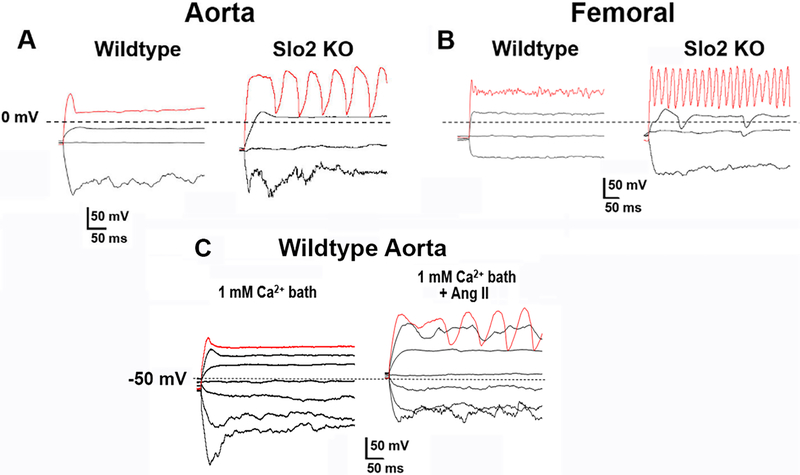

In current clamp SLO2 KO ASM cells have more easily evoked Ca2+-dependent action potentials relative to wild-type.

In current clamp experiments we found that the rheobase for evoking action potentials in SLO2 KO ASM cells was lower than in wild-type ASM cells (Fig. 10). This was true in both aortal and femoral cells. This was further evidence that the SLO2 current stabilizes ASM cells, thereby serving as a buffer dampening excitability. In Fig. 10 we show the voltage changes induced by current injections of the same magnitude in the presence and absence (SLO2 KO) of SLO2 channels in order to determine the contribution of SLO2 currents to excitability. These cells were subject to the same amplitude of current injection, and in both ASM cell types the mutant cells responded with repetitive calcium-dependent graded action potentials, in contrast to the wild-type cells which did not. The action potentials in these cells were shown to be Ca2+-dependent because they were eliminated either by removing extracellular Ca2+ or by addition of the calcium channel blocker verapamil. Notably the duration of the active responses was generally broader in aortal ASMs than femoral ASMs. This may have to do with differences in the active potassium channels present in the different cell types at positive voltages, as well as possible differences in voltage-dependent calcium channels. In Fig. 10C we also show that wild-type ASM cells markedly change their excitable properties when exposed to Ang II and resemble SLO2 KO cells.

Fig. 10. Ca2+ action potentials are more easily evoked in mouse SLO2 KO ASM cells.

(A) Membrane potential changes recorded under current clamp mode from an aortic ASM cell freshly isolated from a 7-week old wild-type mouse (left) or Slo2 KO mouse (right). Hyperpolarizing and depolarizing currents were injected from −150 pA to 250 pA. Dotted black lines indicate 0 mV. Red traces are membrane potential responses after injecting 250 pA currents (~20 pA/pF). Graded Ca2+ action potentials were evoked after injecting 100 pA currents for Slo2 KO cells (7 out of 11 cells); however the same current evoked action potentials in 0 out of 12 wild-type cells. (B) Membrane potential changes recorded under current clamp mode from a femoral ASM cell freshly isolated from a 7-week old wild-type mouse (left) or Slo2 KO mouse (right). The red traces are the membrane potential responses after injecting 250 pA (~20 pA/pF) currents. Graded Ca2+ action potentials were evoked after injecting 100 pA current in Slo2 KO cells (14 out of 19 cells); however the same current evoked action potentials in 0 out of 11 wild-type cells. Action potentials became more regular when injecting more depolarizing currents. Evoked action potentials from Slo2 KO ASM cells were eliminated by the calcium channel blocker verapamil (10 μM). Note: there was no statistical difference in the size of wild-type and KO ASM cells. (C) Ang II makes wildtype arterial smooth muscle cells more excitable. Representative membrane potential changes were recorded under current clamp mode from an aortal smooth muscle cell freshly isolated from a 7-week wild-type mouse. Hyperpolarizing and depolarizing currents were injected from −150 pA to 150 pA at 50 pA increments. Dotted black lines indicate −50 mV. After injecting 150 pA currents (the red traces), no obvious action potentials were observed in the absence of Ang II (left) while regular Ca2+ action potentials were evoked in the presence of 1 μM Ang II (right). In 3 out of 5 cells, Ang II increased the cell excitability. For experiments shown in this figure, the pipette solution contained (in mM): 110 K-Gluconate, 30 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. Under these conditions the intracellular Ca2+ was buffered at approximately 100 nM. The bath solution contained (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH=7.3.

DISCUSSION

KNa channels have unique molecular and functional properties relative to other K+ channels (Kaczmarek, 2013). Once thought to be a reserve conductance active only during periods of hypoxia or ischemia (Dryer, 1994; Kaczmarek, 2013; Kameyama et al., 1984), IKNa now appears to be a significant contributor of outward current to both neurons (Budelli et al., 2009) and ASMs under conditions of normal physiology. Although undetected until now IKNa appears to have been “hiding in plain sight” in ASM cells perhaps for several reasons, one being that expression of IKNa progressively diminishes in cell culture. At the single channel level, IKNa channels might be confused with IKCa BK channels because both are high conductance K+ channels (although IKNa channels have approximately half the single channel conductance of BK channels (Fig. 1) (Salkoff et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2003). At the level of physiological function, however, they seem to play distinctive roles. IKCa BK channels serve an important role as a hyperpolarizing mechanism in response to an increase in cytoplasmic [Ca2+]; one example of this is IKCa’s role in controlling muscle tone during Ca2+ sparks (Brenner et al., 2000; Hill-Eubanks et al., 2011). On the other hand, we find that KNa channels seem to be constitutively active over a wider voltage range, which includes the cell resting potential. As such, they appear to be a significant influence over the cells’ intrinsic excitability.

Properties of KNa channels make them particularly useful to modulate smooth muscle excitability.

The low voltage sensitivity of KNa channels allows them to open over a wide voltage range. Although KNa channels retain a small intrinsic voltage sensitivity, they lack a canonical voltage sensor found in all other voltage-dependent potassium channels (Santi et al., 2006). In addition to permitting them to open over a wide range of voltages, this property also allows them to be subject to neuromodulation at different voltages, and thus able to adjust the resting cell conductance as well as participate in the repolarizing response to excitable stimuli at more positive voltages.

The conditions for activating KNa channels have been poorly understood.

The IKNa current was initially observed in the inside-out patch configuration where the cytoplasmic surface of the patch was exposed to very high concentrations of sodium ion in order to markedly increase channel open time (Kameyama et al., 1984). Consequently it was suggested that IKNa was a current held in reserve to rescue cells from depolarization during stringent conditions when cells were exposed to hypoxic conditions resulting in a significant increase in the concentration of intracellular Na+. Subsequently, several experimental strategies sought to determine whether KNa channels were significantly activated by sodium entering the cell during sodium-dependent action potentials (Dryer, 1994). Although KNa channels may indeed be activated in some excitable cells following transient sodium channel activity we found that in neurons (Budelli et al., 2009; Hage and Salkoff, 2012) and now in ASM cells, the macroscopic component of IKNa largely depends on a small but continuous inward sodium leak current. A sodium leak is present in many neurons and several other cell types such as smooth muscle, which have resting potentials that are significantly more depolarized than the potassium ion equilibrium potential. The small depolarizing inward Na+ leak current can apparently be carried by either voltage-dependent or voltage-independent channels, and is opposed by the hyperpolarizing outward K+ leak current. Such an arrangement allows cells to adjust their membrane potentials either up or down by modulating one or the other (or both) of these leak currents. Remarkably, sodium leak currents also appear to maintain the concentration of sodium ion in the submembrane region (sometimes referred to as “fuzzy space”) (Barry, 2006; Blaustein and Wier, 2007; Verdonck et al., 2004), at a concentration high enough to permit IKNa activation over a wide voltage range (Hage and Salkoff, 2012) so there is no need to radically increase the bulk cytoplasmic concentration of Na+ as originally hypothesized (Kameyama et al., 1984).

Both SLO2.2 (KNa1.1) [KCNT1] and SLO2.1 (KNa1.2) [KCNT2] as well as the sodium leak channel, NALCN, are present in ASM cells.

This result is supported both by RT-PCR (Fig. 7) and a search of publicly available RNA-seq databases (Mele et al., 2015). Indeed, transcripts for all of these genes are present in different arterial smooth muscle types (Mele et al., 2015). Previously it was shown that the two alpha subunits of the KNa channels, SLO2.1 [KNa1.2] and SLO2.2 [KNa1.1 ] form heteromultimers when expressed together (Chen et al., 2009; Santi et al., 2006). These heteromultimers are negatively regulated by PMA and are likely to be the KNa channel form present in ASM cells. Note, however, that homomeric KNa channels constructed only of SLO2.2 (KCNT1) channel subunits are not negatively regulated by PMA nor negatively regulated by stimulation through Gαq protein-coupled receptors (Santi et al., 2006).

Blood Pressure response in wild-type and IKNa knock-out animals.

Genetic analysis with the SLO2 KO strain deleting KCNT1 & KCNT2 produced a modest hypertensive phenotype, but treating the KO animals with hypertensive agents such as phenylepherine and Ang II resulted in a significantly larger increase in blood pressure than in wild-type animals. Such a large response might be expected to most vasoconstrictive agents such as Ang II and phenylephrine, since the loss of potassium conductance in the negative voltage range of the knock-out animals should weaken the cells ability to resist any depolarizing factors. This is supported by the current clamp experiments shown in figure 10 where ASM cells of the SLO2 KO animals depolarize more easily and are clearly more excitable than the wild-type ASM cells. Membrane voltage potential and the ability to resist depolarization are important elements in blood pressure control and some vasopressive agents either cause membrane depolarization or augment the rise in [Ca2+]i upon depolarization. ASM cells have several types of Gαq protein-coupled receptors on their surface such as the α1-adrenergic receptor, and the Ang II receptor. Activation of these receptors by catecholamines or Ang II causes an increase in [Ca2+]i through several different mechanisms (Amberg and Navedo, 2013). Initially phospholipase C is activated via the GqPCR which causes the production of 2 second messengers, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate [Ins(1,4,5)P3] and diacylglycerol (DAG). Ins(1,4,5)P3 then causes the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in a rapid and transient increase in [Ca2+]i. DAG activates protein kinase C and may play additional roles in activating Ca2+ entry. GqPCR receptor stimulation In ASM cells also leads to activation of nonselective cation channels such as TRPM4 (Gonzales and Earley, 2013). TRPM4 is permeable mainly to monovalent cations and its activation will further depolarize ASM cells, which in turn will activate voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, allowing additional Ca2+ influx. After activation of PLC, Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced depletion of the internal Ca2+ store per se will also activate Ca2+ entry via store-operated channels. These channels are responsible for the Ca2+ release–activated current which is thought to be a principal pathway for Ca2+ entry after receptor stimulation. The effect of ASM cell membrane potential is interwoven into several of these mechanisms leading to a rise in [Ca2+]I (Amberg and Navedo, 2013; Gonzales and Earley, 2013).

The bulk of arterial resistance is controlled by small arterioles, rather than large conduits such as the aorta. Vasoconstrictors such as Ang II are more potent on these resistance arteries (Fransen et al., 2016). In future studies it will be interesting to investigate the extent to which SLO2 KNa channels control membrane resting conductance and membrane potential in ASM cells isolated from arterioles from different vascular beds.

KNa channels may be ideal pharmacological targets to treat hypertension.

Several structural and functional features suggest that KNa channels, previously unknown to be in ASM cells, may be a valuable pharmacological target for channel openers to control hypertension. Structurally, KNa channels are unique and lack the canonical voltage sensor found in all other voltage-dependent K+ channels (Santi et al., 2006). Overall KNa [KNa1.1 & 2] channel structure also differs markedly from all of the voltage-sensitive channels and even differs markedly from its high-conductance KCa channel paralogue SLO1 [KCa1.1]. Thus, it presents a unique structural target. Functionally, since KNa channels are normally active at negative physiological membrane potentials and are even a major determinant of ASM cell resting membrane conductance; just a slight nudge by a pharmacological agent to further increase channel open probability could significantly augment resting K+ conductance making the membrane potential more stable, and counteracting all excitatory depolarizing stimuli.

KEY POINTS SUMMARY.

We report here that a sodium-activated potassium current, IKNa, has been inadvertently overlooked in both conduit and resistance arterial smooth muscle cells (ASM).

IKNa is a major K+ resting conductance and is absent in cells of IKNa knockout (KO) mice

The phenotype of the IKNa KO is mild hypertension but KO mice react more strongly than wild-type with raised blood pressure when challenged with vasoconstrictive agents.

IKNa is negatively regulated by angiotensin II acting through Gαq protein-coupled receptors.

In current clamp, KO ASM cells have easily evoked Ca2+-dependent action potentials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Ramon Lorca for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants R21 NS088611–01, R21 MH107955–01 and R01GM114694 to LS, and RO1-HL53325 and RO1-HL105314 to RPM; CMH was supported by NIH grant K08 HL135400. CMS and SKE were supported by (NICHD) R01 HD088097.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Amberg GC, Navedo MF, 2013. Calcium dynamics in vascular smooth muscle. Microcirculation 20(4), 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Huang JM, Reeve HL, Hampl V, Tolarova S, Michelakis E, Weir EK, 1996. Differential distribution of electrophysiologically distinct myocytes in conduit and resistance arteries determines their response to nitric oxide and hypoxia. Circ Res 78(3), 431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry WH, 2006. Na”Fuzzy space”: does it exist, and is it important in ischemic injury? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 17 Suppl 1, S43–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein MP, Wier WG, 2007. Local sodium, global reach: filling the gap between salt and hypertension. Circ Res 101(10), 959–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW, 2000. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407(6806), 870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budelli G, Hage TA, Wei A, Rojas P, Jong YJ, O’Malley K, Salkoff L, 2009. Na+-activated K+ channels express a large delayed outward current in neurons during normal physiology. Nat. Neurosci 12(6), 745–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Kronengold J, Yan Y, Gazula VR, Brown MR, Ma L, Ferreira G, Yang Y, Bhattacharjee A, Sigworth FJ, Salkoff L, Kaczmarek LK, 2009. The N-terminal domain of Slack determines the formation and trafficking of Slick/Slack heteromeric sodium-activated potassium channels. J Neurosci 29(17), 5654–5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorvatova A, Gallo-Payet N, Casanova C, Payet MD, 1996. Modulation of membrane potential and ionic currents by the AT1 and AT2 receptors of angiotensin II. Cell Signal 8(8), 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidad P, Moreno-Dominguez A, Novensa L, Roque M, Barquin L, Heras M, Perez-Garcia MT, Lopez-Lopez JR, 2010. Characterization of ion channels involved in the proliferative response of femoral artery smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30(6), 1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides C, Mean R, Janssen BJ, 2011. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on the cardiovascular function of the C57BL/6 mouse. ILAR J 52(3), e21–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE, 1994. Na(+)-activated K+ channels: a new family of large-conductance ion channels. Trends Neurosci 17(4), 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn B, Dobrev D, 2007. Vascular large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels: functional role and therapeutic potential. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 376(3), 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SK, Wooldridge TA, Stekiel WJ, Rusch NJ, 1993. Enhanced single-channel K+ current in arterial membranes from genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol 264(5 Pt 2), H1337–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira JJ, Butler A, Stewart R, Gonzalez-Cota AL, Lybaert P, Amazu C, Reinl EL, Wakle-Prabagaran M, Salkoff L, England SK, Santi CM, 2018. Oxytocin can regulate myometrial smooth muscle excitability by inhibiting the Na(+/−) activated K(+/−) channel, Slo2.1. J Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen P, Van Hove CE, Leloup AJ, Schrijvers DM, De Meyer GR, De Keulenaer GW, 2016. Effect of angiotensin II-induced arterial hypertension on the voltage-dependent contractions of mouse arteries. Pflugers Arch 468(2), 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales AL, Earley S, 2013. Regulation of cerebral artery smooth muscle membrane potential by Ca(2)(+)-activated cation channels. Microcirculation 20(4), 337–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage TA, Salkoff L, 2012. Sodium-activated potassium channels are functionally coupled to persistent sodium currents. J. Neurosci 32(8), 2714–2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanouz JL, Vivien B, Gueugniaud PY, Lecarpentier Y, Coriat P, Riou B, 1998. Interaction of isoflurane and sevoflurane with alpha- and beta-adrenoceptor stimulations in rat myocardium. Anesthesiology 88(5), 1249–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Eubanks DC, Werner ME, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, 2011. Calcium signaling in smooth muscle. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3(9), a004549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF, 1952. Currents carried by sodium and potassium ions through the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J Physiol 116(4), 449–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan FT, Aldrich RW, 2002. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J Gen Physiol 120(3), 267–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XQ, Zhang L, 2012. Function and regulation of large conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel in vascular smooth muscle cells. Drug Discov Today 17(17–18), 974–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LK, 2013. Slack, Slick and Sodium-Activated Potassium Channels. ISRN Neurosci 2013(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama M, Kakei M, Sato R, Shibasaki T, Matsuda H, Irisawa H, 1984. Intracellular Na+ activates a K+ channel in mammalian cardiac cells. Nature 309(5966), 354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchford KJ, Ferguson AV, 2005. Angiotensin depolarizes parvocellular neurons in paraventricular nucleus through modulation of putative nonselective cationic and potassium conductances. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289(1), R52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux J, Werner ME, Brayden JE, Nelson MT, 2006. Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 21, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorca RA, Wakle-Prabagaran M, Freeman WE, Pillai MK, England SK, 2018. The large-conductance voltage- and Ca(2+) -activated K(+) channel and its gamma1-subunit modulate mouse uterine artery function during pregnancy. J Physiol 596(6), 1019–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Espinosa PL, Wu J, Yang C, Gonzalez-Perez V, Zhou H, Liang H, Xia XM, Lingle CJ, 2015. Knockout of Slo2.2 enhances itch, abolishes KNa current, and increases action potential firing frequency in DRG neurons. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PK, Griendling KK, 2007. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292(1), C82–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele M, Ferreira PG, Reverter F, DeLuca DS, Monlong J, Sammeth M, Young TR, Goldmann JM, Pervouchine DD, Sullivan TJ, Johnson R, Segre AV, Djebali S, Niarchou A, Consortium GT, Wright FA, Lappalainen T, Calvo M, Getz G, Dermitzakis ET, Ardlie KG, Guigo R, 2015. Human genomics. The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science 348(6235), 660–665. www.gtexportal.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavenstadt H, Lindeman S, Lindeman V, Spath M, Kunzelmann K, Greger R, 1991. Potassium conductance of smooth muscle cells from rabbit aorta in primary culture. Pflugers Arch 419(1), 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn SJ, Cornwall MC, Williams GH, 1987. Electrophysiological responses to angiotensin II of isolated rat adrenal glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology 120(4), 1581–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinl EL, Cabeza R, Gregory IA, Cahill AG, England SK, 2015. Sodium leak channel, non-selective contributes to the leak current in human myometrial smooth muscle cells from pregnant women. Mol. Hum. Reprod 21(10), 816–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinl EL, Zhao P, Wu W, Ma X, Amazu C, Bok R, Hurt KJ, Wang Y, England SK, 2018. Na+-Leak Channel, Non-Selective (NALCN) Regulates Myometrial Excitability and Facilitates Successful Parturition. Cell Physiol Biochem 48(2), 503–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch NJ, De Lucena RG, Wooldridge TA, England SK, Cowley AW Jr., 1992. A Ca(2+)-dependent K+ current is enhanced in arterial membranes of hypertensive rats. Hypertension 19(4), 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A, 2006. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci 7(12), 921–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samain E, Bouillier H, Rucker-Martin C, Mazoit JX, Marty J, Renaud JF, Dagher G, 2002. Isoflurane alters angiotensin II-induced Ca2+ mobilization in aortic smooth muscle cells from hypertensive rats: implication of cytoskeleton. Anesthesiology 97(3), 642–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi CM, Ferreira G, Yang B, Gazula VR, Butler A, Wei A, Kaczmarek LK, Salkoff L, 2006. Opposite regulation of Slick and Slack K+ channels by neuromodulators. J. Neurosci 26(19), 5059–5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JB, Brock TA, 1983. Analysis of angiotensin-stimulated sodium transport in cultured smooth muscle cells from rat aorta. J Cell Physiol 114(3), 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammaro P, Smith AL, Hutchings SR, Smirnov SV, 2004. Pharmacological evidence for a key role of voltage-gated K+ channels in the function of rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 143(2), 303–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Wang R, 2001. Differential expression of KV and KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells during 1-day culture. Pflugers Arch 442(1), 124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro L, Stefani E, 1987. Ca2+ and K+ current in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells from rat aorta. Pflugers Arch 408(4), 417–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL, 1999. Activation of the Na(+)-H+ exchanger modulates angiotensin II-stimulated Na(+)-dependent Mg2+ transport in vascular smooth muscle cells in genetic hypertension. Hypertension 34(3), 442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL, 2000. Signal transduction mechanisms mediating the physiological and pathophysiological actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Rev 52(4), 639–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman J, Hargestam R, Lindahl S, Chan SH, Eriksson S, Rundgren M, 2003. Circulatory effects of angiotensin II during anaesthesia, evaluated by real-time spectral analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 47(5), 532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonck F, Mubagwa K, Sipido KR, 2004. [Na(+)] in the subsarcolemmal ‘fuzzy’ space and modulation of [Ca(2+)](i) and contraction in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium 35(6), 603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan A, Santi CM, Wei A, Wang ZW, Pollak K, Nonet M, Kaczmarek L, Crowder CM, Salkoff L, 2003. The sodium-activated potassium channel is encoded by a member of the Slo gene family. Neuron 37(5), 765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan XJ, 1995. Voltage-gated K+ currents regulate resting membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Circ Res 77(2), 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]