Abstract

Background:

Compared to historic ventilation strategies, modern lung-protective ventilation includes lower tidal volumes (VT), lower driving pressures, and application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). The contributions of each component to an overall intraoperative protective ventilation strategy aimed at reducing postoperative pulmonary complications have neither been adequately resolved, nor comprehensively evaluated within an adult cardiac surgical population. We hypothesized that a bundled intraoperative protective ventilation strategy was independently associated with decreased odds of pulmonary complications following cardiac surgery.

Methods:

In this observational cohort study, we reviewed non-emergent cardiac surgical procedures utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass at a tertiary care academic medical center from 2006–2017. We tested associations between bundled or component intraoperative protective ventilation strategies (VT <8 mL/kg ideal body weight, modified driving pressure [peak inspiratory pressure - PEEP] <16cm H2O, and PEEP ≥5cm H2O) and postoperative outcomes, adjusting for previously identified risk factors. The primary outcome was a composite pulmonary complication; secondary outcomes included individual pulmonary complications, postoperative mortality, as well as durations of mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit stay, and hospital stay.

Results:

Among 4,694 cases reviewed, 513 (10.9%) experienced pulmonary complications. Following adjustment, an intraoperative lung-protective ventilation bundle was associated with decreased pulmonary complications (adjusted odds ratio 0.56; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.42–0.75). Via a sensitivity analysis, modified driving pressure <16 cm H2O was independently associated with decreased pulmonary complications (adjusted odds ratio 0.51; 95% CI 0.39–0.66), but VT <8 mL/kg and PEEP ≥5cm H2O were not.

Conclusions:

We identified an intraoperative lung-protective ventilation bundle as independently associated with pulmonary complications following cardiac surgery. Our findings offer insight into components of protective ventilation associated with adverse outcomes and may serve as targets for future prospective interventional studies investigating the impact of specific protective ventilation strategies on postoperative outcomes following cardiac surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs), a well-documented group of complications following cardiac surgery, are associated with a 4-fold increase in mortality,1,2 extended intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital lengths of stay,2,3 and over $20,000 institutional expenses per event.3–5 In the cardiac surgery population, measurable derangements in pulmonary function occur in nearly all patients,6,7 and approximately 10–25% develop PPCs requiring substantial healthcare resource utilization.1,6

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), mechanical ventilation, and surgical manipulation of the thoracic cavity each play major roles in the evolution of pulmonary injury.1 Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors impact a patient’s ability to cope with these insults.7,8 Several externally validated risk scores incorporating these factors have been developed to improve risk stratification for PPCs following cardiac surgery.9,10 Despite rigorous model development, shortcomings of PPC prediction models remain evident. One recent multicenter study demonstrated that a large proportion of variation in pneumonia rates remains unexplained by prediction models focused on surgical technique and underlying patient risk, suggesting that other unmeasured practices may account for the differences observed.11 One such process of care associated with PPCs, yet not accounted for in current prediction models, is the practice of intraoperative lung-protective ventilation (LPV). Compared to historic intraoperative ventilation techniques, modern LPV strategies employ lower tidal volumes (VT),1,4,5,12–15 lower driving pressures (ΔP),16–18 and use of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP).13,15,19 These techniques have already gained acceptance in intensive care units after large studies have demonstrated reduced morbidity and mortality.18,20 However, the contributions of each component to an overall intraoperative LPV strategy aimed at reducing postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) has not been comprehensively studied in an adult cardiac surgical population.

Although ICU ventilation following cardiac surgery has been assessed,21,22 scarce data currently exist evaluating the relationship between intraoperative ventilator management during cardiac surgery, PPCs, and mortality. As the post-CPB intraoperative period represents a unique transition from often non-ventilated to ventilated lungs, optimizing respiratory mechanics to reduce lung injury is of critical concern. To better characterize this currently understudied relationship, we performed an observational cohort study using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG) databases at our institution. We hypothesized that a bundled intraoperative LPV strategy (i.e., lower VT, ΔP, and application of PEEP) was independently associated with decreased odds of PPCs following cardiac surgery, when adjusted within a novel, robust multivariable model leveraging data uniquely available from each database. We additionally hypothesized that when studied as separate exposures, components of the intraoperative bundled LPV strategy had differential associations with PPCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We obtained Institutional Review Board approval (HUM00132314) for this observational cohort study performed at our academic quaternary care center; the requirement for informed patient consent was waived. We adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist for reporting observational studies. Study methods including data collection, outcomes, and statistical analyses were established prospectively and presented at an institutional peer-review committee on January 20, 2016; a revised finalized proposal was registered prior to accessing study data.23

Patient Population

Inclusion criteria for the study were adult (≥18 years) patients who underwent elective or urgent cardiac surgical procedures with full CPB, limited to coronary artery bypass grafting, valve, and aortic procedures, performed in isolation or in combination. We reviewed patients over a continuous 11-year study period from January 1, 2006 to June 1, 2017. Exclusion criteria were preoperative mechanical ventilation within 60 days of surgery, use of a double-lumen endotracheal tube and/or one lung ventilation, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class 5 or 6 physical status, preoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, ventricular assist device implantation procedures (planned and unplanned), reoperative cardiac surgical procedures, transcatheter procedures, or procedures utilizing partial- or left-heart bypass. At our institution, surgical techniques for the study cohort commonly included direct aortic cannulation via full sternotomy, and rarely, axillary or femoral cannulation or direct cannulation via mini-sternotomy. No robotic procedures or minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass procedures were performed.

Data collection

We collected study data from three sources: the MPOG electronic anesthesia database, the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database, and our hospital enterprise electronic health record. Within the MPOG database, physiologic monitors including vital signs and ventilator settings/measurements are collected in automated fashion every 60 seconds and stored in an electronic intraoperative anesthesia record for all cases. Templated intraoperative script elements – including case times, medications and fluids administered, and anesthetic interventions such as airway management techniques – are additionally routinely recorded within the anesthesia record for all cases. Within the STS database, patient history, surgical procedure, and outcome data are similarly stored as discrete concepts for all adult cardiac surgical procedures performed within our institution. To maintain high rates of interobserver agreement across cases, data are standardized using detailed pre-specified definitions, and are collected (STS database)24 or validated (MPOG database) by nurses with completed training in data definitions used. Detailed methods for data entry, validation, and quality assurance are described elsewhere,25–27 and have been utilized for multiple published studies.28–31 Within the MPOG and STS databases, local datasets were linked via unique codified surgical case and patient identifiers; data extraction and analyses were performed on a secure server. Finally, local electronic health record data (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) were used to determine postoperative arterial blood gas values and ICU ventilator data, as necessary for components of outcome variables described below; these data were similarly linked to the final analytic dataset. The quality of local electronic health record data used for this study was verified via manual review by an anesthesiologist investigator (MRM) of all cases experiencing the primary outcome, all cases with outlier data, and 10% of cases not experiencing the primary outcome.

Clinical Processes of Care

Perioperative anesthetic management for all cases was at the discretion of the attending cardiac anesthesiologist, who directs an anesthesia care team of anesthesiology fellows and residents. Routinely, anesthetic agents included induction with midazolam, propofol, or etomidate; analgesia with fentanyl and/or morphine; neuromuscular blockade with rocuronium, vecuronium, or cisatracurium; and maintenance with isoflurane, transitioned to a propofol or dexmedetomidine infusion prior to transport to ICU. In addition to standard monitoring, intraoperative hemodynamic management was routinely guided by invasive arterial line, central venous pressure, and pulmonary artery catheter monitors, as well as transesophageal echocardiography and arterial/mixed venous blood gas measurements. Fluids, blood products, and vasoactive/inotropic infusions were managed at the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist in communication with the cardiac surgeon, with typical hemodynamic targets including a mean arterial pressure >65 mmHg, cardiac index >2.2 L/min/m2, mixed venous oxygen saturation >65%, hematocrit >21%, and echocardiographic assessment of post-CPB ventricular systolic function unchanged to improved compared to pre-CPB function.

Ventilator settings in the operating room were managed by the attending anesthesiologist. Intubation was performed with a 7.5 or 8.0 mm internal diameter endotracheal tube. Mechanical ventilation was performed using Aisys CS2™ anesthesia workstations (General Electric Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Providers typically employed a pressure-controlled volume-guaranteed ventilation mode (default setting) throughout the entire study period, targeting normocapnia or mild hypocapnia, and avoiding hypoxemia. Of note, default settings on ventilators used included VT = 500 mL and PEEP = 0 cm H2O; the default PEEP setting was subsequently changed to PEEP = 5 cm H2O in March 2007. Ventilation was paused during CPB; the ventilator circuit remained connected to the patient, but with no application of PEEP. Prior to discontinuation of CPB, it was resumed after providing recruitment maneuvers. Following transport to ICU, a structured handoff detailing intraoperative management, including final ventilator settings and plan for extubation was communicated to an ICU team of intensivists, nurses, and respiratory therapists. Ventilator weaning, extubation, and management of complications were made at the discretion of the ICU team, as based on local protocols and targeting goals discussed during postoperative handoff.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was occurrence of a PPC, predefined as a composite of pulmonary complications recorded in STS and adjudicated by nurses trained in outcome definitions, or recorded in our enterprise electronic health record and adjudicated by an anesthesiologist (MRM). These included any one of the following: prolonged initial postoperative ventilator duration >24 hours (STS), pneumonia (STS), reintubation (STS), or postoperative partial pressure of oxygen to fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <100 mmHg within 48 hours postoperatively while intubated (local electronic health record, Appendix 1).

We selected a threshold of PaO2/FiO2 <100 mmHg as a PPC component based upon previously validated assessments of pulmonary dysfunction associated with mortality following cardiac surgery.32–34 Given varied mechanisms of pulmonary injury, and the distinction between pneumonia versus other pulmonary complications as described in recent consensus guidelines,35,36 each component of the PPC composite outcome was also separately analyzed as a secondary outcome. Additional predefined secondary outcomes included 30-day postoperative mortality, initial postoperative mechanical ventilation duration, minimum PaO2/FiO2 within 48 hours postoperatively while intubated (as a continuous variable), length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay. All secondary outcomes were similarly adjudicated by trained STS nurse reviewers with the exception of minimum PaO2/FiO2 which was adjudicated by an anesthesiologist (MRM).

Exposure Variables – Lung-Protective Ventilation

The primary exposure variable studied was a bundled intraoperative LPV strategy, comprised of median VT <8 mL/kg predicted body weight and median ΔP <16 cm H2O and median PEEP ≥5 cm H2O. Varying lung-protective cutoffs for each ventilator component are currently described in the literature, ranging from VT 6–10 mL/kg predicted body weight1,13,15, driving pressure 8–19 cm H2O16,18,37, and PEEP 3–12 cm H2O13,15. Given these ranges, our cutoffs were selected by inspection of previously collected ventilation practice institutional data, targeting upper quartiles (approximately 75% compliance for each component) to ensure class balance between cases with LPV versus non-LPV and to improve multivariable model discrimination.5,13,28,38–40

Predicted body weight (PBW, in kg) was calculated as: 50 + 2.3 * (height (in) - 60) for men; 45 + 2.3 * (height (in) - 60) for women.41 Modified airway driving pressure (ΔP) was calculated as (peak inspiratory pressure - PEEP). As performed in previous studies,42 we used modified driving pressure for all cases, given the lack of ventilator plateau pressure data available within our electronic medical record necessary for a true driving pressure calculation. To adjust for decisions to maintain normoxia rather than a LPV strategy (otherwise favoring lower FiO2 and moderate PEEP), intraoperative SpO2 and FiO2 were included as covariates. To summarize each ventilator variable on a per-case basis, median values while mechanically ventilated were calculated. Ventilator parameters while on CPB, during which ventilators were routinely paused, were excluded from the median value calculation. For descriptive purposes, ventilator parameters were additionally subdivided into median value pairs, separated into the pre-CPB and post-CPB periods. In cases with multiple instances of CPB, post-CPB ventilator parameters were analyzed after the final CPB instance.

Covariate Data

For descriptive purposes and to adjust for confounding variables potentially associated with the exposure variables or study outcomes, a range of perioperative characteristics were included as covariates within our study. Patient anthropometric, medical history, anesthetic, surgical, and laboratory testing/study variables were selected as available within the MPOG and STS databases. All variables used in several existing scores for calculating risk of complications including PPCs following cardiac surgery were included (e.g. cardiac surgery type, bypass times, comorbidities, etc.), in addition to other relevant descriptive covariates (Table 1).9,10,43 To evaluate for changes in practice and STS reporting over the study time period, the STS version was included as a covariate; this resulted in four time periods for adjustment (1/1/2006 – 12/31/2007; 1/1/2008 – 6/30/2011; 7/1/2011 – 6/30/2014; 7/1/2014 – 5/31/2017) To account for variation in unmeasured intraoperative practices attributable to the attending anesthesiologist and potentially associated with PPCs, we characterized attending anesthesiologists by tertiles of low/medium/high frequency of bundled intraoperative LPV use.

Table 1:

Perioperative Patient Characteristics and Univariate/Bivariate Associations with Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

| Characteristic | Entire Cohort N = 4694 n (%) or mean(SD)/median [interquartile range] |

Postoperative Pulmonary Complication | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No N=4181 (89.1%) n (%) or mean(SD)/median [interquartile range] |

Yes N = 513 (10.9%) n (%) or mean(SD)/median [interquartile range] |

P-value | % Cases with Complete Data | ||

| Preoperative Characteristics | |||||

| Age | 62 (14) | 62 (14) | 64 (14) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Sex, male | 3024 (64.4) | 2730 (65.3) | 294 (57.3) | 0.0004 | 100 |

| Race, non-white | 515 (11.0) | 442 (10.6) | 73 (14.2) | 0.0127 | 99.9 |

| Height, cm | 172 (11) | 172 (10) | 170 (11) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Actual Body Weight, kg | 86.9 (21.0) | 87.0 (20.8) | 85.8 (22.8) | 0.2624 | 100 |

| Predicted Body Weight, kg | 65.8 (11.1) | 66.1 (11.0) | 63.6 (11.6) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Class III Obesity (≥40) | 315 (6.7) | 268 (6.4) | 47 (9.2) | ||

| Current Smoker | 630 (13.4) | 551 (13.2) | 79 (15.4) | 0.1637 | 100 |

| Chronic Lung Disease * | 543 (11.6) | 444 (10.6) | 99 (19.3) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Recent Pneumonia within one month | 55 (1.2) | 45 (1.1) | 10 (2.0) | 0.0829 | 100 |

| Sleep Apnea | 490 (10.4) | 442 (10.6) | 48 (9.4) | 0.3957 | 100 |

| Severe (PA systolic pressure >55 mmHg) | 262 (5.6) | 208 (5.0) | 54 (10.7) | ||

| IV | 125 (2.7) | 93 (2.3) | 32 (6.3) | ||

| Recent Myocardial Infarction < 21 days | 329 (7.0) | 275 (6.6) | 54 (10.5) | 0.0009 | 100 |

| Preoperative Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, % | 60 [55, 65] | 60 [55, 65] | 60 [50, 65] | 0.0003 | 100 |

| Poor Mobility ** | 2353 (50.1) | 2030 (48.6) | 323 (63.0) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Previous Major Vascular Surgical Intervention | 224 (4.8) | 188 (4.5) | 36 (7.0) | 0.0115 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 2703 (57.6) | 2419 (57.9) | 284 (55.4) | 0.2803 | 100 |

| Arrhythmia *** | 735 (15.7) | 626 (15.0) | 109 (21.3) | 0.0002 | 100 |

| Dialysis Requirement | 104 (2.2) | 72 (1.7) | 32 (6.2) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Diabetes treated with Insulin | 374 (8.0) | 312 (7.5) | 62 (12.1) | 0.0003 | 100 |

| Liver Disease | 77 (1.6) | 69 (1.7) | 8 (1.6) | 0.8785 | 100 |

| Cancer | 225 (4.8) | 204 (4.9) | 21 (4.1) | 0.4318 | 100 |

| Active Endocarditis | 238 (5.1) | 197 (4.7) | 41 (8.0) | 0.0014 | 100 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 58 (1.2) | 34 (0.8) | 24 | <.0001 | 100 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.5 (1.9) | 13.6 (1.9) | 12.6 (2.2) | <.0001 | 99.7 |

| Platelet Count, K/uL | 225 (69) | 225 (68) | 223 (77) | 0.6178 | 99.7 |

| White Blood Cell Count, K/uL | 6.8 [5.7, 8.3] | 6.8 [5.7, 8.2] | 7.4 [6.0, 9.1] | <.0001 | 99.7 |

| International Normalized Ratio | 1.0 [1.0, 1.1] | 1.0 [1.0, 1.0] | 1.0 [1.0, 1.1] | <.0001 | 99.6 |

| Preoperative SpO2, % | 97 [96, 98] | 97 [96, 98] | 97 [95, 98] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Preoperative Respiratory Rate | 16 [16, 18] | 16 [16, 18] | 16 [16, 18] | 0.0015 | 97.0 |

| Urgent | 954 (20.3) | 772 (18.5) | 182 (35.5) | ||

| Valve + CABG | 536 (11.4) | 433 (10.4) | 103 (20.1) | ||

| Inpatient | 1206 (25.7) | 984 (23.5) | 222 (43.3) | ||

| 2.81 (July 2014-May 2017) | 1380 (29.4) | 1281 (30.6) | 99 (19.3) | ||

| 4 | 3218 (68.6) | 2815 (67.3) | 403 (78.6) | ||

| Intraoperative Characteristics | |||||

| Perfusion Time, hours | 2.2 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.3) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Aortic Crossclamp Time, hours | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.2 (1.1) | <.0001 | 99.7 |

| Anesthesia Duration, hours | 6.5 [5.4, 7.9] | 6.4 [5.3, 7.7] | 7.7 [6.4, 9.4] | <.0001 | 100 |

| High LPV User | 361 (7.7) | 321 (7.7) | 40 (7.8) | ||

| Intraoperative Albuterol | 57 (1.2) | 46 (1.1) | 11 (2.1) | 0.0416 | 100 |

| Intraoperative Diuretic ****** | 2898 (61.7) | 2588 (61.9) | 310 (60.4) | 0.5179 | 100 |

| Intraoperative Vasopressor infusion (phenylephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) | 4294 (91.5) | 3815 (91.3) | 479 (93.4) | 0.1036 | 100 |

| Intraoperative Inotrope infusion (epinephrine, dobutamine, milrinone, isoproterenol, dopamine) | 1723 (36.7) | 1397 (33.4) | 326 (63.6) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Total intraoperative opioid, oral morphine equivalents | 300 [270, 360] | 300 [270, 360] | 300 [240, 375] | 0.0177 | 99.9 |

| Total intraoperative crystalloid, L | 3.0 [2.0, 4.3] | 3.0 [2.0, 4.1] | 3.4 [2.3, 5.3] | <.0001 | 98.8 |

| Total intraoperative colloid, L | 0 [0, 0.5] | 0 [0, 0.5] | 0 [0, 0.5] | 0.3498 | 100 |

| Intraoperative packed red blood cells, units | 0 [0,2] | 0 [0, 2] | 2 [0, 4] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Intraoperative red blood cell salvage, L | 0 [0,0] | 0 [0, 0] | 0 [0, 0] | 0.9154 | 100 |

| Intraoperative Fresh frozen plasma, units | 0 [0,0] | 0 [0, 0] | 0 [0, 2] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Intraoperative Platelets, units | 0 [0, 0] | 0 [0, 0] | 0 [0, 2] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Intraoperative Cryoprecipitate, units | 0 [0, 0] | 0 [0, 0] | 0 [0, 0] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Total urine output, L | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.4) | 0.4361 | 99.1 |

| Pre-CPB Ventilation / Respiratory Parameters | |||||

| Tidal volume, mL/kg predicted body weight | 7.8 (1.5) | 7.8 (1.5) | 8.1 (1.7) | 0.0001 | 100 |

| Peak Inspiratory Pressure, cm H2O | 17 [15, 20] | 17 [15, 20] | 19 [16, 22] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Positive End-Expiratory Pressure, cm H2O | 5 [4, 5] | 5 [4, 5] | 5 [2, 5] | 0.0359 | 100 |

| Driving Pressure, cm H2O | 13 [11, 16] | 13 [11, 16] | 15 [12, 18] | <.0001 | 100 |

| SpO2, % | 99 [98, 100] | 99 [98, 100] | 99 [99, 100] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Inspired FiO2, % | 97 [96, 98] | 97 [95, 98] | 97 [96, 98] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Post-CPB Ventilation / Respiratory Parameters | |||||

| Tidal volume, mL/kg predicted body weight | 7.8 (1.5) | 7.7 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.6) | <.0001 | 100 |

| Peak Inspiratory Pressure, cm H2O | 18 [15, 20] | 17 [15, 20] | 20 [17, 23] | <.0001 | 100 |

| Positive End-Expiratory Pressure, cm H2O | 5 [4, 5] | 5 [4, 5] | 5 [4, 5] | 0.7216 | 100 |

| Driving Pressure, cm H2O | 13 [11, 16] | 13 [11, 16] | 16 [13, 19] | <.0001 | 100 |

| SpO2, % | 100 [99, 100] | 100 [99, 100] | 100 [98, 100] | 0.4913 | 100 |

| Inspired FiO2, % | 97 [96, 98] | 97.0 [96, 98] | 97 [96, 98] | 0.0033 | 100 |

| Overall Ventilation | |||||

| Bundled LPV Strategy ******* | 1913 (40.8) | 1787 (42.7) | 126 (24.6) | <.0001 | 100 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CPB= cardiopulmonary bypass; FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; LPV = lung-protective ventilation; PA = pulmonary artery; STS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Defined by chronic lung disease ≥ moderate or bronchodilator therapy within STS; or COPD ≥ moderate on preoperative anesthesia history & physical

Defined by functional capacity – Low (≤4 metabolic equivalents of task) on preoperative anesthesia history & physical

Defined via STS as a history of any of the following: atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, 3rd degree heart block, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia

Calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease – Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation

Defined as the frequency of primary anesthesiology attending using a bundled LPV strategy, as a proportion of all cardiac cases performed by the anesthesiology attending among the study population, transformed into tertiles.

Defined as intraoperative administration of furosemide, bumetanide, or mannitol

Defined as intraoperative median values of: tidal volume <8 mL/kg predicted body weight, positive end-expiratory pressure ≥5 cm H2O, and driving pressure <16 cm H2O

P-value from independent t-Test, Mann-Whitney U test, or Chi-Square Test, as appropriate.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Normality of continuous variables was graphically assessed using histograms and Q-Q plots. Continuous data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range; binary data were summarized via frequency and percentage. Comparisons of continuous data were made using a two-tailed independent t-test or a Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical data were compared by a Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Trend analyses of the components of the LPV bundle were completed using the Cochran-Armitage test. A p-value of <0.05 denoted statistical significance.

Prior to any multivariable analyses, collinearity among covariates was assessed using the variance inflation factor; variables with a variance inflation factor >10 were excluded. To target development of a clinically usable reduced-fit PPC multivariable model avoiding overfitting, covariates meaningfully describing the study population but not used in existing cardiac surgery risk score models were additionally excluded from multivariable analyses. Missing data were handled via a complete case analysis. To further aid in covariate selection, we used the least absolute shrinkage and selection operators technique and restricted covariates to the number of outcomes divided by 10, while also accounting for the LPV bundle as well as LPV bundle components (VT, ΔP and PEEP). We chose this variable selection technique, given its ability to perform regularization and variable selection to improve model accuracy and interpretability, particularly among analyses with a relatively large number of covariates and modest number of outcomes.44 Using a multivariable logistic regression model, we characterized the risk-adjusted association between the primary exposure of intraoperative LPV bundle and the primary outcome of postoperative pulmonary complication. Additionally, we repeated our multivariable analysis to assess independent associations between each LPV bundle component and PPCs. Overall model discrimination of logistic regression models was assessed using the c-statistic. Secondary outcomes were assessed using multivariable linear regression models. Goodness-of-fit for linear regression models was summarized via R-squared; such models were evaluated using varied distributional assumptions (i.e. linear versus logarithmic transformations) for continuous secondary outcomes. Multilevel modelling clustering at the provider level was not possible due to limited sample size per provider; instead, the previously mentioned fixed covariate of anesthesiology attending LPV frequency tertile was used.

In addition to analyzing independent associations between an overall LPV strategy and the PPC primary outcome, we performed several sensitivity analyses, including an analysis of LPV separated into component parts: VT <8 mL/kg PBW, ΔP <16 cm H2O, or PEEP ≥5 cm H2O, and analyses of LPV strategies separately examined before and after CPB.

We also performed a sensitivity analysis, using a model that further restricted the number of covariates to the number of outcomes divided by 20.45 Additionally, we compared our multivariable PPC model developed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator for covariate selection, to a multivariable PPC model including all non-collinear covariates with p<0.10. Finally, we performed subgroup analyses stratified by salient clinical characteristics.

RESULTS

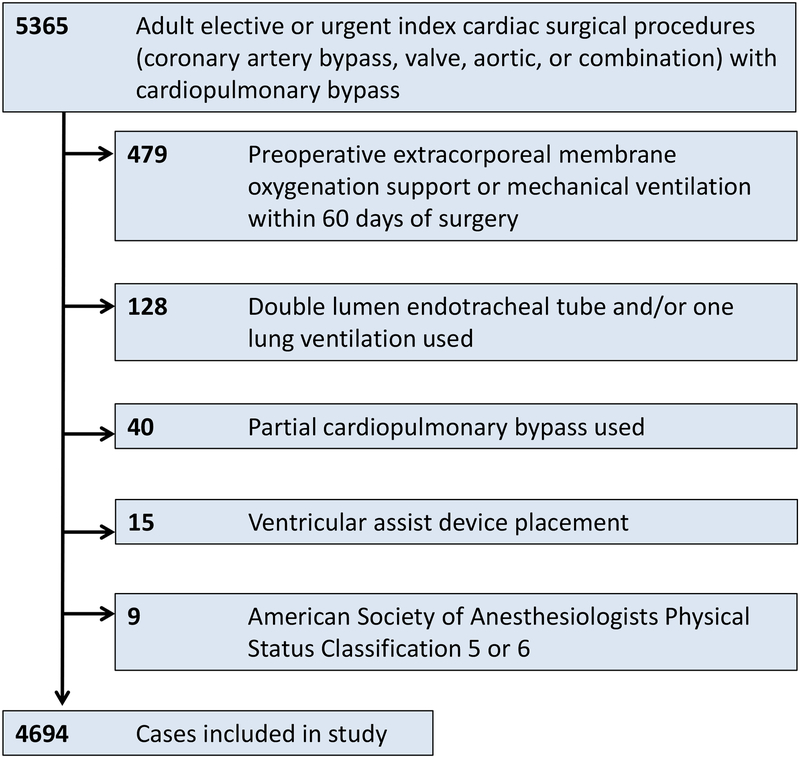

Of the 5,365 cardiac surgical cases reviewed, 4,694 met study inclusion criteria (fig. 1). Among these cases, 513 (10.9%) experienced a PPC. Individual non-mutually exclusive components of PPCs included pneumonia (121 cases, 23.6% of PPCs), prolonged ventilation >24 hours, (302, 58.9% of PPCs), reintubation (115, 22.4% of PPCs), and PaO2/FiO2 <100 mmHg (164, 32.0% of PPCs).

Fig. 1:

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Patient Population - Baseline Characteristics & Univariate Analyses

As described in Table 1, our study population had a median age of 62 years, and 64% were men. Cardiac surgeries performed included coronary artery bypass grafting (20.6%), valve (44.3%), aorta (2.1%), and combination (33.0%). Cases were primarily elective (79.7%); remaining cases were urgent (20.3%). Our study population included cases across four time partitions by STS version, including 349 (7.4%) from 1/1/2006 – 12/31/2007; 1,286 (27.4%) 1/1/2008 – 6/30/2011; 1,679 (35.8%) 7/1/2011 – 6/30/2014; 1,380 (29.4%) 7/1/2014 – 5/31/2017. An overall LPV strategy was used in 1,913 cases (40.8%); among components of a LPV strategy, a VT <8 mL/kg PBW was achieved in 64% of cases, modified driving pressure ΔP <16 cm H2O in 71% of cases, and PEEP ≥5 cm H2O in 63% of cases. Adherence to varying thresholds and independent associations with PPCs are provided in Supplemental Digital Content 1A–1C. Crude incidence of PPCs among cases using an overall LPV strategy was 6.6%, compared to 13.9% among cases without an overall LPV strategy (Table 2). PPCs were associated with increased postoperative mortality as well as longer postoperative mechanical ventilation, ICU stay, and hospital stay (Table 3). Patients receiving a LPV strategy were more commonly tall, non-obese, male, and non-smokers (Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Table 2:

Summary of Primary Study Outcomes, Primary Outcome Components, and Bundled Lung-Protective Ventilation Strategy

| Entire Cohort N = 4694 |

Bundled LPV Strategy * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, 59.3% (n = 2781) |

Yes, 40.7% (n = 1913) |

p-value | ||

| PaO2/FiO2 <100 mmHg*** | 164 (3.8) | 131 (5.2) | 33 (1.9) | <.0001 |

FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; LPV = lung-protective ventilation; PaO2 = arterial partial pressure of oxygen

Defined as intraoperative median values of: <8 mL/kg predicted body weight, positive end-expiratory pressure ≥5 cm H2O, and driving pressure <16 cm H2O

Defined as initial postoperative mechanical ventilation >24 hours

Within 48 hours postoperatively while intubated

P-value from independent t-Test or Chi-Square Test, as appropriate.

Table 3:

Summary of Primary Study Outcomes, Secondary Study Outcomes, and Bundled Lung-Protective Ventilation Strategy

| Entire Cohort N = 4694 |

Postoperative Pulmonary Complication | Bundled LPV Strategy * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, 89.1% (n = 4181) |

Yes, 10.9% (n = 513) |

p-value | No, 59.3% (n = 2781) |

Yes, 40.7% (n = 1913) |

p-value | ||

| 30-Day Postoperative Mortality | 49 (1.0) | 19 (0.5) | 30 (5.9) | <.0001 | 35 (1.3) | 14 (0.7) | 0.0810 |

| Total Hospital Length of Stay | 7.5 (6.7) | 6.5 (3.9) | 15.7 (14.4) | <.0001 | 8.1 (7.8) | 6.7 (4.4) | <.0001 |

ICU = intensive care unit; LPV = lung-protective ventilation

Defined as intraoperative median values of: <8 mL/kg predicted body weight, positive end-expiratory pressure ≥5 cm H2O, and driving pressure <16 cm H2O

P-value from independent t-Test or Chi-Square Test, as appropriate.

Intraoperative Ventilator Management

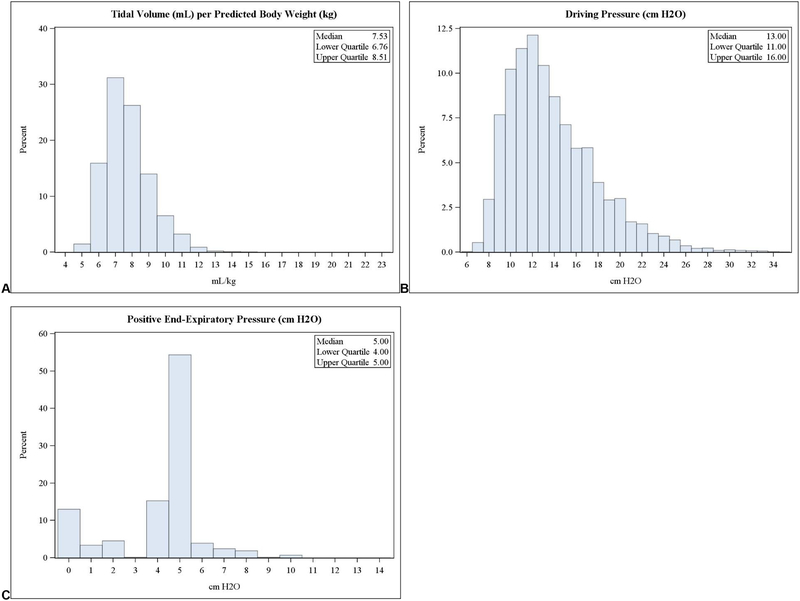

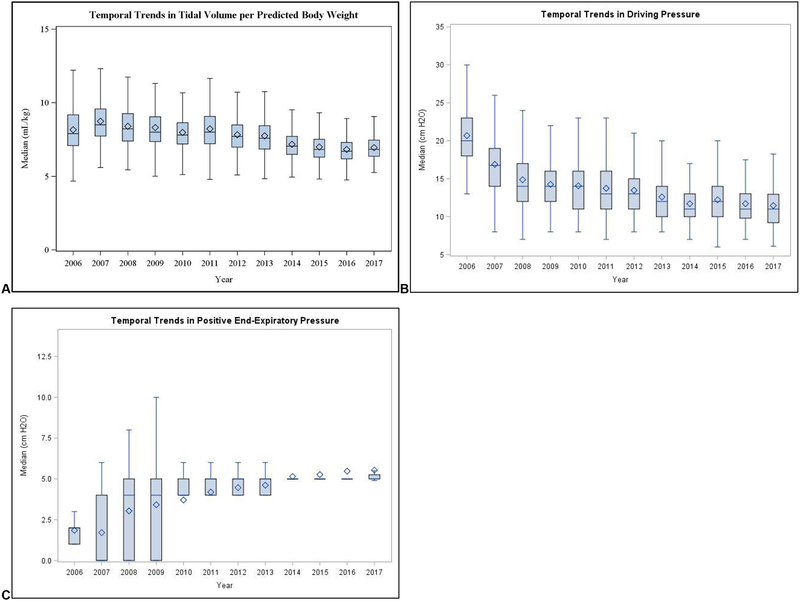

Patients were ventilated with a cohort mean ± SD VT of 7.8 ± 1.5 mL/kg PBW, and median (interquartile range) ΔP of 13 (11–16) cm H2O; and PEEP of 5 (4–5) cm H2O. Compared to pre-CPB ventilator parameters, we observed no significant differences in post-CPB parameters (Table 1). We observed distributions of overall per-case median ventilator parameters to be unimodal and rightward-skewed for VT and ΔP, versus a bimodal distribution (0 cm H2O and 5 cm H2O) for PEEP (fig. 2). Over the study period, we observed significant linear trends in ventilation practices: providers employed decreasing VT and ΔP, and increasingly employed PEEP (p <0.001 for all trends, fig. 3).

Fig. 2:

Frequency distributions of per-case median intraoperative ventilator parameters, including tidal volume per predicted body weight, modified driving pressure, and positive end-expiratory pressure (in left, middle, and right panels, respectively).

Fig. 3:

Temporal trends in intraoperative ventilator strategies, including tidal volume per predicted body weight, modified driving pressure, and positive end-expiratory pressure (in left, middle, and right panels, respectively).

Impact of Ventilator Parameters - Multivariable Analyses

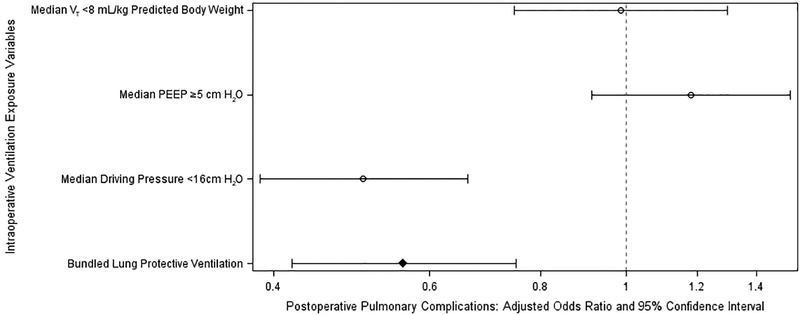

Of the 4,694 cases studied, we observed data completeness rates >99% for all but two risk adjustment variables, preoperative respiratory rate (97.0%) and total intraoperative crystalloid (98.8%). Peak inspiratory pressure and weight were removed from the model due to multicollinearity (variance inflation factor >10). Platelet count, international normalized ratio, total intraoperative opioid, preoperative respiratory rate, and history of cancer were removed, given a lack of use in previous validated cardiac surgery or PPC risk score models.9,10,43 Multiple additional variables were removed via least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (denoted by “-” in Supplemental Digital Content 3). Through multivariable analyses adjusting for PPC risk factors, an intraoperative LPV bundle was independently associated with reduced PPCs (adjusted odds ratio 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.42–0.75, fig. 4 and 5). Modelling LPV exposure as a “treatment”, we observed a “number needed to expose” of 18 (95% CI 14–33) in order to prevent one PPC.

Fig. 4:

Independent associations between intraoperative lung protective ventilation strategies and postoperative pulmonary complications.

Fig. 5:

Significant independent associations between multivariable model components and postoperative pulmonary complications.

We observed no associations between a LPV bundle and minimum postoperative PaO2/FiO2 while intubated, initial postoperative ventilator duration in hours, length of ICU stay in hours, or length of hospital stay in days (Supplemental Digital Content 4). We observed similar findings for logarithmically transformed secondary outcomes. Postoperative mortality occurred in 49 cases (1.0%); our study was not adequately powered to analyze independent associations between LPV and mortality.

Among individual pulmonary complications (pneumonia, prolonged ventilation >24 hours, reintubation, and PaO2/FiO2 <100 mmHg postoperatively while intubated), a LPV bundle demonstrated univariate associations across all PPC components; following multivariable adjustment, a LPV bundle remained protective against all PPC components except for prolonged ventilation >24 hours (Supplemental Digital Content 5 and 6).

Sensitivity Analyses

When analyzing each component of the LPV bundle separately, we found that modified driving pressure ΔP <16 cm H2O was independently associated with reduced PPCs (adjusted odds ratio 0.51, 95% CI 0.39–0.66) whereas VT <8 mL/kg PBW and PEEP ≥5 cm H2O did not demonstrate significant independent associations (adjusted odds ratios [95% CIs] 0.99 [0.75–1.30] and 1.18 [0.91–1.53] respectively, fig. 4). Furthermore, ΔP <16 cm H2O was independently associated with improvements in all secondary outcomes.

When analyzing the LPV bundle as partitioned into pre-CPB and post-CPB periods, we observed no collinearity between corresponding pre-CPB and post-CPB variables (variance inflation factors <10) and thus included all variables into a single model. We found that adherence to the post-CPB LPV bundle was associated with less PPCs (adjusted odds ratio 0.53, 95% CI 0.38–0.74) whereas the pre-CPB LPV bundle was not associated with PPCs (adjusted odds ratio 1.19, 95% CI 0.84–1.68, Supplemental Digital Content 7). Similarly, when analyzing the LPV components individually partitioned into pre-CPB and post-CPB periods, we observed no collinearity between corresponding pre-CPB and post-CPB components and thus included all variables into a single model. We observed post-CPB ΔP <16 cm H2O was associated with lesser likelihood of PPC (adjusted odds ratio 0.57, 95% CI 0.42–0.78), but neither the pre-CPB ΔP <16 cm H2O (adjusted odds ratio 0.77, 95% CI 0.56–1.07) nor VT <8 mL/kg PBW nor PEEP ≥5 cm H2O pre-CPB and post-CPB components was associated with PPCs.

Logistic regression models using either least absolute shrinkage and selection of operator restricted to 24 covariates, or forward selection of univariate association thresholds (p<0.10) found independent associations between LPV, ΔP and PPCs, but not VT or PEEP (Supplemental Digital Content 8, 9). Finally, sensitivity analyses of clinically important subgroups yielded similar independent associations between the LPV bundle and outcomes. The protective association of the LPV bundle was observed in both males and females, in elective but not urgent cases, across all body mass index ranges, only in patients without chronic lung disease, and in patients undergoing valve procedures (Supplemental Digital Content 10).

DISCUSSION

Using robust, validated observational databases, we report an overall pulmonary complication incidence of 10.9% after cardiac surgery, and identify an intraoperative lung-protective ventilation bundle as independently associated with a clinically and statistically significant reduction in pulmonary complications. Our study builds upon existing literature by providing an analysis of the impact of intraoperative ventilation strategies on postoperative outcomes among a generalizable cardiac surgery population. Although unaccounted for in current risk scoring systems, we report that an intraoperative LPV strategy is independently associated with development of PPCs. Through a sensitivity analysis evaluating components of the LPV bundle, we importantly note that ΔP, but not VT or PEEP, is independently associated with PPCs.

Compared to prior literature, our findings demonstrate the importance of considering multiple components of LPV when evaluating the impact of mechanical ventilation on outcomes. Notably, we observed that not all components of LPV were independently associated with decreased PPCs; however, a LPV bundled approach was independently associated with decreased PPCs. Furthermore, within the LPV bundle studied, we observed ΔP as the component primarily driving the association with reduced PPCs, rather than VT or PEEP. These findings offer insight towards sustaining a trend of expedited recovery from cardiac surgery, a process in which postoperative care teams are increasingly reliant on intraoperative practices – such as LPV – to target reduced postoperative complications and to safely enable rapid de-escalation of care upon arrival to the ICU.46,47

Our study highlights the importance of ΔP, and conversely the limitations of VT and PEEP, as independently associated with PPCs and secondary outcomes. We offer two hypotheses to explain these findings: (i) increased ΔP is a marker for non-compliant lungs, assuming such patients are at increased risk of PPCs and remain unidentified by model covariates; and/or (ii) increased ΔP reflects direct pulmonary injury via barotrauma as a PPC mechanism. Countervailing to a hypothesis that ΔP serves as a marker for non-compliance, however, was our observation that lower VT was not independently associated with increased PPCs, as would be the case for increasingly non-compliant lungs at a given constant ΔP exposure (controlled covariate). This finding was similarly observed in an analysis performed among 3,562 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome enrolled across nine randomized trials.17 Within a surgical population, a recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated a driving pressure-guided ventilation strategy during one-lung ventilation to be similarly associated with a lower incidence of PPCs compared to conventional ventilation strategies, during thoracic surgery.49

Additionally of note, in a sensitivity analysis analyzing pre-CPB ΔP and post-CPB ΔP separately, our observations that (i) pre-CPB and post-CPB variables were not collinear and (ii) post-CPB ΔP but not pre-CPB ΔP <16 cm H2O was independently associated with PPCs, suggests our ΔP findings cannot solely be explained as a marker for poor baseline lung function. However, whether this independent association between post-CPB ΔP <16 cm H2O and PPCs remains explained by a direct lung injury hypothesis, versus a marker for varying degrees of CPB-induced pulmonary dysfunction, remains unanswerable based on our data. Other explanations for a lack of collinearity between pre-CPB and post-CPB ΔP may include nuanced surgery stage-specific ventilation strategies, such as low VT and low ΔP during internal mammary artery surgical dissection and/or cannulation prior to CPB. Finally, although a ΔP threshold of <16 cm H2O enabled class balance between cases adherent versus non-adherent to an overall LPV bundle, an “optimal” ΔP threshold defining LPV remains unclear, and likely varies by clinical context.

Our findings that lower intraoperative ΔP was associated with improved outcomes suggest an opportunity for improved care through the implementation of an LPV protocol favoring lower ΔP. Additionally, our observation that intraoperative ΔP, but not VT or PEEP, was independently associated with PPCs, reflects a potential benefit of individualized ventilation strategies among patients with varying respiratory compliance (ignored with VT - targeted ventilator management) or varying volume of aerated functional lung (ignored with uniform application of PEEP). However, given the observational nature of this study, our findings require prospective interventional evaluation and validation prior to large-scale adoption of the technique.

Our 10.9% observed incidence of PPCs is consistent with previous studies.1,6 However, this comparison is challenged by varied definitions of a PPC, which remain subject to debate. Our PPC definition is consistent with international consensus guidelines35,36 and was derived from clinician-adjudicated data available within STS or our electronic health record. Nonetheless, other recognized components of PPCs include (i) atelectasis defined by radiographic evidence,35 (ii) pulmonary aspiration defined by clinical history and radiographic evidence,35 (iii) pleural effusion defined by radiographic evidence,36 (iv) pneumothorax,35 (v) bronchospasm defined by expiratory wheezing treated with bronchodilators,36 or (vi) aspiration pneumonitis.36 We determined a priori to exclude these additional PPC components in our composite outcome on the basis of either unclear clinical significance in a cardiac surgical population, underlying mechanisms likely not amenable to treatment via LPV, or lack of access to component-specific high-fidelity data across all patients in the study cohort.

Study Limitations

Our study possessed several limitations. First, we were unable to account for all potential mechanisms leading to a composite PPC. Mechanisms for pulmonary injury following cardiac surgery are multifactorial.7 In our study, we investigate LPV as a means to reduce ventilator-induced lung injury, leading to PPCs through mechanisms including volutrauma, barotrauma, and atelectasis, and respectively mitigated by lower VT, lower ΔP, and application of PEEP.8 However, additional PPC mechanisms to be targeted by anesthesiologists include (i) pulmonary edema, mitigated by fluid and transfusion management,50 (ii) inadequate respiratory effort, mitigated by monitoring/reversal of neuromuscular blockade51,52 or rapid-acting, opioid-limiting anesthetic agents,48 and (iii) respiratory infection, mitigated by ventilator associated pneumonia prevention bundles.53,54 In our study, we successfully accounted for several of these targets as covariates. However, the relative importance of each technique, and the impact of LPV on the association between such techniques and PPCs, remains beyond the scope of this study.

In our study, precise times for sternotomy and chest closure were unavailable; however cases excluded redo-sternotomies with protracted closed chest times. As such, driving pressures were assessed during open-chest conditions for a majority of intraoperative ventilation. Our study adds new data to studies of protective ventilation, previously performed during closed-chest conditions. As this relates to the driving pressures observed, our study may demonstrate comparatively less bias introduced by variable chest wall compliance. Thus, airway driving pressure in this study is likely to more closely reflect actual transpulmonary driving pressure, a determinant of dynamic lung strain.55 Despite this strength, we caution generalizing our findings to more commonly studied patient populations ventilated under closed-chest conditions. We additionally caution generalizing our driving pressure threshold <16 cm H2O as LPV without consideration of clinical context. In previous studies of cardiac surgical populations,16,37 thresholds for LPV defined by driving pressure (plateau pressure - PEEP) ranged from 8–19 cm H2O. Such variation may be explained by (i) time of measurement (e.g. intraoperative versus postoperative), (ii) surgical conditions (e.g. closed-chest versus open-chest), (iii) patient populations and practice patterns varying by year and institution, and (iv) covariates used for multivariable adjustment. However, it should be noted that despite such sources of variation influencing driving pressure-based LPV thresholds, independent associations between increased ventilator driving pressures and increased postoperative complications have been consistently observed.

Additional limitations to our study include those inherent to our single-center, observational study design: our conclusions require prospective multicenter validation. Patients receiving a LPV bundle were non-random; although multiple covariates associated with the LPV exposure were accounted for via multivariable analyses, unmeasured confounders influencing receiving a LPV bundle and impacting our PPC primary outcome was a source of potential bias. As pertaining to our LPV exposure variable, limitations included a lack of formal Pplat ventilator data for more accurate characterization of driving pressure. Although differences between ventilator peak inspiratory pressure and Pplat may be approximated in specified circumstances, the availability of all data necessary for calculations - and the degree to which confounding factors may bias such calculations (e.g. patient differences in airway resistance, endotracheal tube obstructions from kinking/secretions, and the use of end-inspiratory pressure to approximate inspiratory pause pressure for calculating true Pplat) - remain beyond the scope of our study.

Consistent with existing literature,1,28 we represented the intraoperative period using LPV exposure median values – potentially failing to account for brief periods of profoundly injurious ventilation. Finally, although our study goal was to specifically examine relationships between intraoperative ventilation and PPCs, relationships between postoperative ventilation and PPCs were not studied.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, our study advances understanding of the relationship between intraoperative LPV and impact on costly, life-threatening PPC outcomes. In summary, we describe a 10.9% incidence of PPCs among adults undergoing cardiac surgery. Importantly, we observed that a bundled LPV strategy was independently associated with a lower likelihood of PPCs and that this was mostly associated with lower ΔP. Through robust capture of variables describing intraoperative anesthesia management for cardiac surgery patients, our study provides data which may better inform PPC multivariable models in this population. Additionally, our findings offer targets for future prospective trials investigating the impact of specific LPV strategies for improving cardiac surgery outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge Tomas Medina Inchauste, B.S.E. and Anik Sinha, M.S. (Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and Jeremy Wolverton, M.S. (Department of Cardiac Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for their contributions in data acquisition and electronic search query programming for this project.

Funding Statement:

All work and partial funding attributed to the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). The project was supported in part by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, Grant 2446-PIRAP, Detroit, MI. Additionally, the project was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medicine Sciences, Grant T32-GM103730–04, Bethesda, MD. Dr. Likosky received support (R01-HS-022535) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Strobel received support (TL1-TR-002242) from the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, or Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Appendix 1: Postoperative Pulmonary Complications - Data Definitions

| Postoperative Pulmonary Complication Component | Data Source | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged initial postoperative ventilator duration >24 hours | STS database | Yes/No Indicate whether the patient had prolonged postoperative pulmonary ventilation > 24.0 hours. |

| Pneumonia | STS database | Yes/No Indicate whether the patient had pneumonia according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention definition. |

| Reintubation | STS database | Yes/No Indicate whether the patient was reintubated during the hospital stay after the initial extubation. This may include patients who have been extubated in the OR and require intubation in the postoperative period. |

| Postoperative PaO2:FiO2 <100 mmHg within 48 hours postoperatively while intubated | Hospital enterprise electronic health record (Epic Systems Corporation ©, Verona, WI) | Yes/No Indicate whether the patient had a postoperative PaO2:FiO2 <100 mmHg within 48 hours while intubated:

|

FiO2 = Fraction of inspired oxygen; PaO2 = Arterial partial pressure of oxygen; STS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests beyond those described in the funding statement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zochios V, Klein AA, Gao F: Protective Invasive Ventilation in Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review With a Focus on Acute Lung Injury in Adult Cardiac Surgical Patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibanez J, Riera M, Amezaga R, Herrero J, Colomar A, Campillo-Artero C, Ibarra JI de, Bonnin O: Long-Term Mortality After Pneumonia in Cardiac Surgery Patients: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. J Intensive Care Med 2016; 31:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown PP, Kugelmass AD, Cohen DJ, Reynolds MR, Culler SD, Dee AD, Simon AW: The frequency and cost of complications associated with coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: results from the United States Medicare program. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 85:1980–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Delgado M, Navarrete-Sanchez I, Colmenero M: Preventing and managing perioperative pulmonary complications following cardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2014; 27:146–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lellouche F, Delorme M, Bussieres J, Ouattara A: Perioperative ventilatory strategies in cardiac surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2015; 29:381–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hulzebos EH, Helders PJ, Favie NJ, De Bie RA, Brutel de la Riviere A, Van Meeteren NL: Preoperative intensive inspiratory muscle training to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications in high-risk patients undergoing CABG surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006; 296:1851–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apostolakis E, Filos KS, Koletsis E, Dougenis D: Lung dysfunction following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Card Surg 2010; 25:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slinger P, Kilpatrick B: Perioperative lung protection strategies in cardiothoracic anesthesia: are they useful? Anesthesiol Clin 2012; 30:607–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, Paluzie G, Valles J, Castillo J, Sabate S, Mazo V, Briones Z, Sanchis J: Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology 2010; 113:1338–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shroyer AL, Coombs LP, Peterson ED, Eiken MC, DeLong ER, Chen A, Ferguson TB Jr, Grover FL, Edwards FH: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons: 30-day operative mortality and morbidity risk models. Ann Thorac Surg 2003; 75:1856–64; discussion 1864–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brescia AA, Rankin JS, Cyr DD, Jacobs JP, Prager RL, Zhang M, Matsouaka RA, Harrington SD, Dokholyan RS, Bolling SF, Fishstrom A, Pasquali SK, Shahian DM, Likosky DS: Determinants of Variation in Pneumonia Rates After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 105:513–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu WJ, Wang F, Liu JC: Effect of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes on clinical outcomes among patients undergoing surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ 2015; 187:E101–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guldner A, Kiss T, Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Canet J, Spieth PM, Rocco PR, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M: Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications: a comprehensive review of the role of tidal volume, positive end-expiratory pressure, and lung recruitment maneuvers. Anesthesiology 2015; 123:692–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guay J, Ochroch EA: Intraoperative use of low volume ventilation to decrease postoperative mortality, mechanical ventilation, lengths of stay and lung injury in patients without acute lung injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD011151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Biehl M, Binnekade JM, Canet J, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Futier E, Gajic O, Hedenstierna G, Hollmann MW, Jaber S, Kozian A, Licker M, Lin WQ, Maslow AD, Memtsoudis SG, Reis Miranda D, Moine P, Ng T, Paparella D, Putensen C, Ranieri M, Scavonetto F, Schilling T, Schmid W, Selmo G, Severgnini P, Sprung J, Sundar S, Talmor D, Treschan T, Unzueta C, Weingarten TN, Wolthuis EK, Wrigge H, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ: Protective versus Conventional Ventilation for Surgery: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2015; 123:66–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neto AS, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Futier E, Gajic O, El-Tahan MR, Ghamdi AA, Gunay E, Jaber S, Kokulu S, Kozian A, Licker M, Lin WQ, Maslow AD, Memtsoudis SG, Reis Miranda D, Moine P, Ng T, Paparella D, Ranieri VM, Scavonetto F, Schilling T, Selmo G, Severgnini P, Sprung J, Sundar S, Talmor D, Treschan T, Unzueta C, Weingarten TN, Wolthuis EK, Wrigge H, Amato MB, Costa EL, de Abreu MG, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ: Association between driving pressure and development of postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for general anaesthesia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4:272–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, Brochard L, Costa EL, Schoenfeld DA, Stewart TE, Briel M, Talmor D, Mercat A, Richard JC, Carvalho CR, Brower RG: Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:747–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoyama H, Pettenuzzo T, Aoyama K, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Fan E: Association of Driving Pressure With Mortality Among Ventilated Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:300–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmes SN, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ: High versus low positive end-expiratory pressure during general anaesthesia for open abdominal surgery (PROVHILO trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 384:495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin MA, McCormick PJ, Lin HM, Hosseinian L, Fischer GW: Low intraoperative tidal volume ventilation with minimal PEEP is associated with increased mortality. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113:97–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lellouche F, Dionne S, Simard S, Bussieres J, Dagenais F: High tidal volumes in mechanically ventilated patients increase organ dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:1072–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu F, Gomersall CD, Ng SK, Underwood MJ, Lee A: A randomized controlled trial of adaptive support ventilation mode to wean patients after fast-track cardiac valvular surgery. Anesthesiology 2015; 122:832–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anesthesia Clinical Research Committee at <https://anes.med.umich.edu/research/acrc.html>

- 24.Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database Data Specifications 2017. at <https://www.sts.org/sites/default/files/documents/ACSD_DataSpecificationsV2_9.pdf>

- 25.Freundlich RE, Kheterpal S: Perioperative effectiveness research using large databases. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25:489–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kheterpal S: Clinical research using an information system: the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. Anesthesiol Clin 2011; 29:377–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shroyer AL, Edwards FH, Grover FL: Updates to the Data Quality Review Program: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac National Database. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 65:1494–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bender SP, Paganelli WC, Gerety LP, Tharp WG, Shanks AM, Housey M, Blank RS, Colquhoun DA, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Jameson LC, Kheterpal S: Intraoperative Lung-Protective Ventilation Trends and Practice Patterns: A Report from the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesth Analg 2015; 121:1231–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs JP, He X, O’Brien SM, Welke KF, Filardo G, Han JM, Ferraris VA, Prager RL, Shahian DM: Variation in ventilation time after coronary artery bypass grafting: an analysis from the society of thoracic surgeons adult cardiac surgery database. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96:757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kheterpal S, Healy D, Aziz MF, Shanks AM, Freundlich RE, Linton F, Martin LD, Linton J, Epps JL, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Jameson LC, Tremper T, Tremper KK: Incidence, predictors, and outcome of difficult mask ventilation combined with difficult laryngoscopy: a report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. Anesthesiology 2013; 119:1360–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Filardo G, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, Normand SL, DeLong ER, Shewan CM, Dokholyan RS, Peterson ED, Edwards FH, Anderson RP: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1--coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2009; 88:S2–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esteve F, Lopez-Delgado JC, Javierre C, Skaltsa K, Carrio ML, Rodriguez-Castro D, Torrado H, Farrero E, Diaz-Prieto A, Ventura JL, Manez R: Evaluation of the PaO2/FiO2 ratio after cardiac surgery as a predictor of outcome during hospital stay. BMC Anesthesiol 2014; 14:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardenas-Turanzas M, Ensor J, Wakefield C, Zhang K, Wallace SK, Price KJ, Nates JL: Cross-validation of a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score-based model to predict mortality in patients with cancer admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2012; 27:673–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012; 307:2526–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbott TEF, Fowler AJ, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M, Moller AM, Canet J, Creagh-Brown B, Mythen M, Gin T, Lalu MM, Futier E, Grocott MP, Schultz MJ, Pearse RM: A systematic review and consensus definitions for standardised end-points in perioperative medicine: pulmonary complications. Br J Anaesth 2018; 120:1066–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M, Smith A, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, Leva B, Rhodes A, Hoeft A, Walder B, Chew MS, Pearse RM: Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015; 32:88–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladha K, Vidal Melo MF, McLean DJ, Wanderer JP, Grabitz SD, Kurth T, Eikermann M: Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation and risk of postoperative respiratory complications: hospital based registry study. BMJ 2015; 351:h3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Futier E, Constantin Jm, Fau-Paugam-Burtz C, Paugam-Burtz C, Fau-Pascal J, Pascal J, Fau-Eurin M, Eurin M, Fau-Neuschwander A, Neuschwander A, Fau-Marret E, Marret E, Fau-Beaussier M, Beaussier M, Fau-Gutton C, Gutton C, Fau-Lefrant J-Y, Lefrant Jy, Fau-Allaouchiche B, Allaouchiche B, Fau-Verzilli D, Verzilli D, Fau-Leone M, Leone M, Fau-De Jong A, De Jong A, Fau-Bazin J-E, Bazin Je, Fau-Pereira B, Pereira B, Fau-Jaber S, Jaber S: A trial of intraoperative low-tidal-volume ventilation in abdominal surgery 20130801 DCOM- 20130806 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schultz MJ, Haitsma JJ, Slutsky AS, Gajic O: What tidal volumes should be used in patients without acute lung injury? Anesthesiology 2007; 106:1226–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Douville NJ, Jewell ES, Duggal N, Blank R, Kheterpal S, Engoren MC, Mathis MR: Association of Intraoperative Ventilator Management With Postoperative Oxygenation, Pulmonary Complications, and Mortality 2019:p 1 doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000004191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1301–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blum JM, Stentz MJ, Dechert R, Jewell E, Engoren M, Rosenberg AL, Park PK: Preoperative and intraoperative predictors of postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome in a general surgical population. Anesthesiology 2013; 118:19–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chalmers J, Pullan M, Fabri B, McShane J, Shaw M, Mediratta N, Poullis M: Validation of EuroSCORE II in a modern cohort of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 43:688–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tibshirani R: Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the LASSO. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1996; 58:267–88 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katz MH: Multivariable analysis: a primer for readers of medical research. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:644–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stephens RS, Whitman GJ: Postoperative Critical Care of the Adult Cardiac Surgical Patient. Part I: Routine Postoperative Care 2015. 0617 DCOM- 20150826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens RS, Whitman GJ: Postoperative Critical Care of the Adult Cardiac Surgical Patient: Part II: Procedure-Specific Considerations, Management of Complications, and Quality Improvement. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:1995–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong WT, Lai VK, Chee YE, Lee A: Fast-track cardiac care for adult cardiac surgical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 9:Cd003587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park M, Ahn HJ, Kim JA, Yang M, Heo BY, Choi JW, Kim YR, Lee SH, Jeong H, Choi SJ, Song IS: Driving Pressure during Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2019; 130:385–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans RG, Naidu B: Does a conservative fluid management strategy in the perioperative management of lung resection patients reduce the risk of acute lung injury? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012; 15:498–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hristovska AM, Duch P, Allingstrup M, Afshari A: Efficacy and safety of sugammadex versus neostigmine in reversing neuromuscular blockade in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 8:Cd012763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy GS, Brull SJ: Residual neuromuscular block: lessons unlearned. Part I: definitions, incidence, and adverse physiologic effects of residual neuromuscular block. Anesth Analg 2010; 111:120–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damas P, Frippiat F, Ancion A, Canivet JL, Lambermont B, Layios N, Massion P, Morimont P, Nys M, Piret S, Lancellotti P, Wiesen P, D’Orio V, Samalea N, Ledoux D: Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia and ventilator-associated conditions: a randomized controlled trial with subglottic secretion suctioning. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahmoodpoor A, Hamishehkar H, Hamidi M, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, Golzari SE, Khan ZH, Nader ND: A prospective randomized trial of tapered-cuff endotracheal tubes with intermittent subglottic suctioning in preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 2017; 38:152–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henderson WR, Chen L, Amato MBP, Brochard LJ: Fifty Years of Research in ARDS. Respiratory Mechanics in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196:822–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.