Abstract

Iron is essential for the pathogenicity and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which synthesises salicyl-capped siderophores (mycobactins) to acquire this element from the host. MbtA is the adenylating enzyme that catalyses the initial reaction of mycobactins’ biosynthesis and is solely expressed by mycobacteria. A 3,200-member library comprised of lead-like, structurally-diverse compounds was screened against M. tuberculosis for whole-cell inhibitory activity. A set of 846 compounds that inhibited the tubercle bacilli growth were then tested for their ability to bind to MbtA using a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay and NMR-based Water-LOGSY and Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) experiments. We identified an attractive hit-molecule, 5-hydroxy-indol-3-ethylamino-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethyl)benzene (5), that bound with high affinity to MbtA and produced a MIC90 of 13 μM. The ligand was docked into the MbtA crystal structure and displayed an excellent fit within the MbtA active pocket, adopting a different binding mode to the established MbtA inhibitor Sal-AMS.

Keywords: Tuberculosis drug discovery, phenotypic and target-based screening, mycobactins / siderophores, mycobacterial iron homeostasis, NMR Water-LOGSY, Saturation Transfer Difference, NMR spectroscopy, Fluorescent-based Thermal Shift Assay

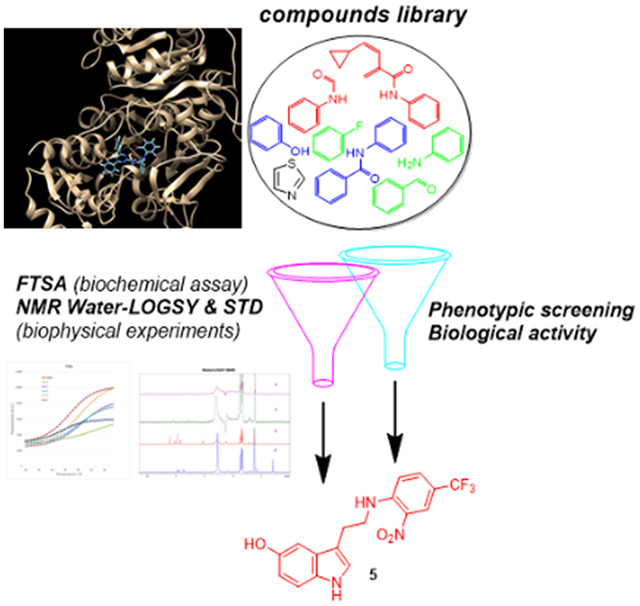

Graphical Abstract

An integrated target-based and phenotypic screening method was developed and deployed to identify 5-hydroxy-indol-3-ethylamino-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethyl)benzene (5) as an attractive hit-molecule that bound with high affinity to MbtA, producing a MIC90 of 13 μM.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by the slow-growing Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). In 2017, 10.4 million people contracted TB and 1.7 million died from this disease, with over 95% of TB deaths occurring in developing countries.[1] The alarming rise of multi-drug resistant (MDR)- and extensively-drug resistant (XDR)-TB, particularly in Europe,[2] and the increased rate of HIV-TB co-infection pose additional challenges for the control of this disease that nowadays represents a global health threat.[3] Therefore, new therapeutic agents with novel mechanisms of action(s) are urgently needed to combat the TB pandemic.

M. tuberculosis, similar to other pathogens, requires iron to support its colonisation and growth.[4] Free iron is highly restricted in human serum and body fluids, and M. tuberculosis produces salicyl-capped siderophores, mycobactins (1), to chelate and internalise this essential trace element from the host iron-binding proteins (Figure 1).[5],[6] Mycobactin T (1a) is highly lipophilic and remains associated with the cell wall of mycobacteria, whereas carboxymycobactin (1b), which by virtue of its short carboxylic acid sidechain is more polar, is released into the extracellular medium by the pathogen to chelate the precious iron element.[7],[7b] The mycobactins core structures are comprised of a 2-hydroxyphenyloxazolidine moiety linked to an acylated ε-N-hydroxylysine residue esterified at the α-carboxyl with a 3-hydroxybutyric acid. The latter forms an amide bond with a second ε-N-hydroxylysine that is cyclised to give a seven-membered lactam.[8]

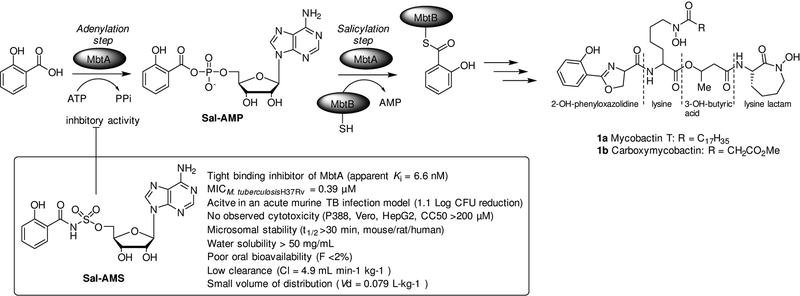

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the initial two-step reaction in the biosynthesis of mycobactins 1a and 1b carried out by the bifunctional enzyme MbtA. The first step involves adenylation of salicylic acid to form Sal-AMP, which is then loaded by MbtA on to the thiolation domain of MbtB. The nucleoside antibiotic Sal-AMS, which is the sulfamoyl-linker containing derivative of Sal-AMP, inhibits the adenylation reaction catalysed by MbtA.14a,b

Following the annotation of the M. tuberculosis genome sequence,[9] a locus of 10 genes (mbtA-J) encoding for a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-polyketide synthase (NRPS-PKS) system was identified to be responsible for the assembly of the mycobactin peptide core.[8, 10] The initial two-step reaction of mycobactin biosynthesis is catalysed by the aryl-adenylating enzyme MbtA (Figure 1). MbtA activates salicylic acid (adenylation step) by forming Sal-AMP, which is then loaded (acylation step) onto the phosphopantetheinylation domain of MtbB, an aryl carrier protein that is also part of the NRPS-PKS cluster.[11] MbtA has no homologues in humans and has been chemically validated as a target for designing new anti-TB drugs.[12] Strains of M. tuberculosis mutants unable to produce mycobactins or import these siderophores with chelated iron have been shown to have in vitro and in vivo attenuated virulence and limited growth in the lung or macrophages.[6, 11, 13] Furthermore, nucleoside antibiotics, such as 5′-O-[N-(salicyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine (Sal-AMS), specifically designed to inhibit MbtA enzymatic activity effectively arrested M. tuberculosis growth and virulence (Figure 1).[14] Taken together these observations show that targeting the mycobactin biosynthesis pathway would prove successful in TB drug development.[15] However, these MbtA inhibitors lack drug-like features, and exhibit poor DMPK profiles and off-target biological activity.[14a]

Herein, we sought to identify novel anti-tubercular agents with high-binding-affinity for MbtA by combining whole-cell screening and target-based drug discovery approaches.[16] To this end, a library of diverse, lead-like small molecules was tested for whole-cell growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) and robust biochemical (fluorescence-based thermal shift) and biophysical (NMR-based Water-LOGSY and STD) assays were employed to test the ability of the H37Rv-active molecules to bind to MbtA.

Results and Discussion

Primary HTS whole-cell screen

A library of 3200 lead-like, structurally-diverse compounds was carefully selected from commercial sources and tested against M. tuberculosis H37Rv at a single concentration of 20 μM using a previously developed 384-well high-throughput screening format.[17] We found that 846 library members exhibited M. tuberculosis growth inhibitory activity ranging from 35% (302 compounds) to >98% (19 compounds). In order to explore the MbtA enzyme chemical space as broadly as possible, it was decided not to apply a percent-inhibition cutoff and all 846 H37Rv-active molecules were investigated for their ability to bind to MbtA using the fluorescent-based thermal shift assay (FTSA).

MbtA production and Fluorescent-based Thermal Shift Assay (FTSA)

M. tuberculosis MbtA (salicyl-AMP ligase) showed a high level of expression in Escherichia coli and was initially elected to be the substrate for the FTSA. However, this enzyme proved to be insoluble and difficult to purify after expression.

Focus was then directed towards the Mycobacterium smegmatis MbtA (2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-AMP ligase) homologue, which shares 69.2% sequence identity and 85.0% sequence similarity with M. tuberculosis MbtA.[18a,b] M. smegmatis MbtA was successfully cloned and heterologously expressed in E. coli to a high yield (30 mg/mL). Purification by affinity chromatography yielded a protein with an apparent mass of 58 kDa, as observed by SDS-PAGE, which was consistent with the predicted 57,656.45 Da molecular mass for M. smegmatis MbtA.

Next, having obtained sufficient quantities of soluble MbtA, the binding affinity of the 846 H37Rv-active molecules was evaluated using real-time PCR-coupled FTSA. The latter is a well-established method that enables accurate monitoring of protein denaturation upon heating via fluorescent-based detection.[19] The fluorescent probe binds with high affinity to the protein’s hydrophobic regions, which are exposed during the course of the experiment. Protein denaturation is visualised via a thermal melting curve, whose mid-point (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the protein has denatured.[19] Upon ligand binding to the protein, the protein Tm increases and the difference in melting temperature (ΔTm) between the protein alone and the protein-ligand adduct serves as a measure of the binding affinity of the ligand.[20]

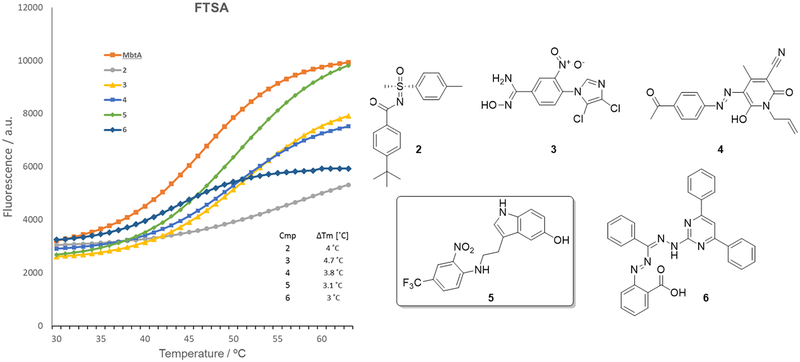

In our experiments, all 846 H37Rv-active molecules were screened at a concentration of 10 μM and a threshold of ΔTm >3°C was applied for the selection of compounds to be progressed to the NMR-based analysis. ATP and Sal-AMS, which was synthesised according to published methods (Supporting Information),[21] were used as positive controls showing ΔTm values of 3.5 and 7.6°C (Figure S1 in Supporting Information), respectively. The graph in Figure 2 illustrates the thermal melting curves and the structures of the five hit-compounds (2-6) identified through FTS screening. As can be noticed, these H37Rv-active MbtA ligands bear diverse chemical scaffolds, which include tolyl-sulfoximine-benzamide 2 (ΔTm = 4°C), dichloroimidazolyl-nitrobenzimidamide 3 (ΔTm = 4.7°C), phenyldiazenyl-pyridone 4 (ΔTm = 3.8°C), 5-hydroxy-indol-3-ethylamino-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethyl)benzene 5 (ΔTm = 3.1°C) and 4,6-diphenylpyrimidin-hydrazono(methyl)(phenyl)(diazenyl) benzoic acid 6 (ΔTm = 3°C).

Figure 2.

Thermal unfolding of MbtA in the presence and absence of five chemically diverse scaffolds (2-6) identified through FTSA.

Anti-tubercular activity and cytotoxicity of hit-compounds

At this stage, MbtA active-hits 2, 3, and 5 and non-binders 4, 6 were tested for whole-cell growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined at five days. MbtA-binder 5 showed the highest anti-tubercular activity with a MIC value of 13 μM, whereas compounds 2, 3, 4 and 6 were considered as not H37Rv-active (Table 1).

Table 1.

a Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 2 - 6 in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and cytotoxicity evaluation in HepG2 cells in presence of glucose (Glu) and galactose (Gal). Activity of compounds 2 - 6 against intracellular M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

| Minimum inhibitory concentrations (μM) | Intracellular assay (μM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | H37Rv MIC90[b] | HepG2 (Glu) IC50[c] | HepG2 (Gal) IC50[c] | Ratio (Glu/Gal) | RAW 264.7 IC50[d] | Intracellular Mtb IC90[e] |

| 2 | >20 (0) | 79 (0.6) | 34 (1.1) | 2.3 | 39 (4.6) | >33 (4.8) |

| 3 | >20 (0) | >100 (0) | >100 (0) | N/A | >100 (0) | >100 (0) |

| 4 | >20 (0) | 69 (1.2) | 41 (0.7) | 1.7 | 8 (1.1) | >3.7 (0) |

| 5 | 13 (2.5) | 36 (0) | 29 (0.5) | 1.2 | 29 (0.5) | 9.3 (0.8) |

| 6 | >20 (0) | >100 (0) | 22 (1.9) | >4.5 | 2.6 (0.6) | >3.7 (1.1) |

| Rifampicin | 0.1 (0.6) | >100 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

The experiments were conducted in triplicate and error values are reported in brackets as Standard Deviation (STDEV) values.

MIC90 was defined as the concentration required to inhibit growth of M. tuberculosis in liquid medium by 90% after 5 days.

IC50 is the concentration required to reduce viability of HepG2 cells (cultured with either glucose or galactose) by 50% after 2 days.

IC50 is the concentration required to reduce viability of RAW 264.7 cells by 50% after 3 days.

IC90 is the concentration required to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis in liquid medium by 90% after 3 days. NA = not available.

The cytotoxicity of the compounds was determined using HepG2 cells and mitochondrial toxicity was assessed by using either high-galactose or glucose-containing media. Replacing glucose with galactose in the media induces HepG2 cells to rely on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation rather than glycolysis for ATP production, and increases their susceptibility to mitochondrial toxicants.[22] Compound 3 exhibited no cytotoxicity and 2 - 5 showed mild to moderate cytotoxicity with IC50 values ranging from 29–79 μM towards cells grown in both media. Interestingly, 6 targeted mitochondrial respiration (Glu/Gal > 4.5).

Measurement of compounds activity against intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Compounds 2 - 6 intracellular activity in Mtb-infected macrophages was evaluated using a live-cell fluorescence-based screen.[23] The assay measured the compounds cytotoxicity and anti-mycobacterial activity simultaneously and provided valuable information about the ability of 2 - 6 to penetrate the macrophages, where Mtb usually resides, and inhibit the growth of intracellular Mtb. As there is evidence that macrophages’ environment is iron-restricted with concentrations of free iron (Fe3+) ranging from 1 – 10 ng ml−1,[24,25] it is anticipated that the intracellular iron-limiting conditions in mammalian macrophages might induce Mtb to produce MbtA enzymes for the synthesis of Fe3+-chelating mycobactins. The results (Table 1) showed that 5 was able to kill intracellular M. tuberculosis at a concentration of 9.3 μM with moderate cytotoxicity (29 μM) against the macrophages, thus confirming the anti-tubercular and cytotoxic activities of this compound. Interestingly, compounds 4 and 6 were found to be more toxic against RAW 264.7 (8 and 2.6 μM, respectively) compared to HepG2 cells and showed enhanced anti-tubercular activity inside the macrophages (>3.7 μM), probably due to intracellular metabolic modification, and additional experiments will be required to investigated this further.

Water-LOGSY and STD NMR assays validates FTSA assay hits

Target-based 1H-NMR spectroscopy experiments, i.e., Water-Ligand Observed Gradient SpectroscopY (Water-LOGSY) and Saturation Transfer Difference (STD),[26, 27] were used to confirm binding of anti-tubercular compounds 5 to MbtA. Water-LOGSY NMR spectra show positive signals for ligands that bind to a protein target compared with negative signals for ligands that do not bind. The STD experiment yields a set of signals for ligands that bind to the target protein when the ligand/protein on/off exchange rate is sufficiently fast to generate saturation transfer effects. Ligands that do not bind do not show NMR responses in the STD data. Both experiments are required to be run with ligand only and ligand in the presence of protein target in order to eliminate the possibility of false positive results.

Sal-AMS showed positive responses in both the STD and Water-LOGSY experiments. Control Water-LOGSY experiments for nitrophenyl-amino ethyl indole 5 carried out in the absence of MbtA showed negative responses for the aromatic signals indicating lack of ligand aggregation, an important prerequisite for ensuring that the generated data were reliable and free from artefacts. Compound 5 showed positive responses in both the STD and Water-LOGSY experiments (Figures S2 and S3 in Supporting Information). STD NMR data clearly indicated ligand binding to MbtA at the on/off exchange rate associated with weak interaction, when MbtA was loaded with the ligand. Buffer salts, contained in the protein solution medium, and DMSO did not bind to the protein, producing negative signals in the aliphatic proton resonance region of the Water-LOGSY spectrum. This is an encouraging result, and more experimental work is currently underway to evaluate the biochemical and enzymatic activity of the purified MbtA in the presence of compounds 5.

In silico docking and binding energy calculations (Modelling)

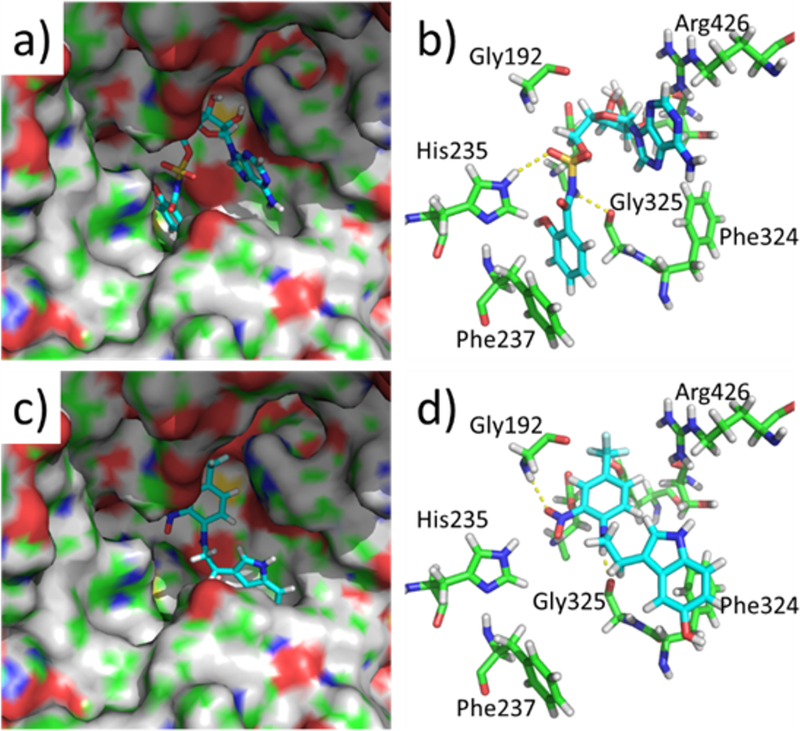

The crystal structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis MbtA in its apo form has been described recently (PDB Ref 5KEI).[18] We have used this structure to dock the compounds Sal-AMS and 5 into the proposed ligand binding pocket using Autodock Vina (Figure 3). The ligands are predicted to occupy different binding orientations in the protein. The Sal-AMS is positioned with the salicyl group occupying a deep pocket in the protein and stacking with Phe237, and the purine ring lies adjacent to Arg426 near to the protein surface.

Figure 3.

Structures of docked compounds (Sal-AMS and 5) within the M. smegmatis MbtA active site derived from PDB Ref 5KEI: a. and b. Docked conformation of Sal-AMS; c. and d. Docked conformation of compound 5. The ligands are represented as sticks and the protein shown as a surface (a. and c.) or selected residues shown as green sticks (c. and d.). Polar interactions are shown as yellow dotted lines. Figures were constructed using The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7 Schrödinger, LLC.

The sulphonamide is predicted to form hydrogen bond interactions with His235 and Gly325. Compound 5 is positioned with its indole ring over Phe324, the phenyl nitro substituent interacts with Gly192 and the amine NH of the ligand is predicted to form a hydrogen bond with Gly325. The predicted binding energies of the two compounds (Sal-AMS −9.3 Kcal/mol, 5 −8.2 Kcal/mol) are similar, but suggest that 5 may be more ligand efficient due to its smaller size (32 and 26 non-H atoms for Sal-AMS and 5 respectively). These observations will require confirmation in future quantitative binding experiments and structural studies, but may be useful to guide initial exploration of structure-activity relationships.

Conclusions

Most of the current anti-TB drugs have been identified by or derived from M. tuberculosis whole-cell screening.[28] However, the lack of knowledge regarding endogenous targets represents the main disadvantage of this approach, greatly limiting the possibilities for improving the potency and selectivity of the active hits. An alternative method to generate anti-tubercular lead-compounds relies on target-based biochemical screens, although so far there has been limited success in using this strategy, due to the difficulty of translating potent target inhibition into whole-cell anti-mycobacterial activity. To this end, we have applied an integrated target-based and phenotypic screening method to identify M. tuberculosis-active molecules that are also able to bind to a well-defined target, i.e., MbtA.

With the aid of fluorescence-based thermal shift and NMR-based Water-LOGSY and STD assays we have identified 5-hydroxy-indol-3-ethylamino-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethyl)benzene (5) as a promising MbtA-ligand that inhibited M. tuberculosis growth, with a MIC90 of 13 μM, and showed relatively low cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Compound 5 exhibited one of a TB drug’s crucial characteristics, which is the ability to kill intracellular M. tuberculosis and permeate the mycobacterial cell envelope to exert bactericidal activity, and, most importantly, was found to strongly interact with the tubercular enzyme MbtA, a newly emerging TB target that catalyses the first two-step reaction of mycobactins’ biosynthesis. In summary, a strong correlation was established between the anti-tubercular activity of the hit-molecule 5 and its ability to bind to the TB-target MbtA. This would provide a suitable biological and chemical starting point for lead-optimisation experiments and MbtA-inhibition activity assays.

Experimental Section

A 3,200-member library (BioAscent Ltd.) of lead-like, structurally-diverse compounds was selected using the following criteria: 3 out of 5 Lipinski rules, i.e., MW<500, HBD<5, HBA<10; rotatable bonds<10; PSA<120 Å. Filters applied to avoid unstable/chemically reactive/toxic fragments, bio-reactive or known pan assay interference compounds (PAINS).

Cloning expression and purification of MbtA (2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-AMP ligase). Cloning, expression and purification were conducted as part of the Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease (SSGCID)[29] following standard protocols described previously.[30] Genomic DNA from Mycobacterium smegmatis ATCC 700084/mc(2)155 was obtained from the ATCC Global Bioresource Center (cat.nr. ATCC 700084D-5). The full-length protein (UniProt: A0R0V0) encoding amino acids 24–558 was PCR amplified from genomic DNA using the primers FWD 5’-CTCACCACCACCACCACCATATGGGATTCACGCCGTTTCCGG and REV 3’-ATCCTATCTTACTCACTTACCCGCCGAGCTGACGCACG. The gene was cloned into the ligation independent cloning (LIC)[31] expression vector pBG1861[30b] encoding a non-cleavable 6xHis fusion tag (MAHHHHHH-ORF). Plasmid DNA was transformed into chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3)R3 Rosetta cells. Cells were expression tested and 2 litres of culture were grown using auto-induction media[32] in a LEX Bioreactor (Epiphyte Three Inc.) as previously described.[30a] The expression clone was assigned the SSGCID target identifier MysmA.00629.c.B2.GE39512 and is available at https://ssgcid.org/available-materials/expression-clones/. MysmA.00629.c.B2 protein was purified in a two-step protocol consisting of an Ni2+-affinity chromatography (IMAC) step and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). All chromatography runs were performed on an ÄKTApurifier 10 (GE) using automated IMAC and SEC programs according to previously described procedures.[30a] The final SEC was performed on a HiLoad 26/600 Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) using a mobile phase of 25 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, 2 mM DTT, and 0.025% Azide. Peak fractions eluted as a single peak of approximately 58 kDa. Peak fractions were pooled and analyzed for the presence of the protein of interest using SDS–PAGE. The peak fractions were concentrated to 30 mg/mL using an Amicon purification system (Millipore). Aliquots of 200 μL were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

HTS and MICs were determined against M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) according to published methods. [17] Briefly, M. tuberculosis was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth medium containing 10% OADC (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, catalase) supplement (Becton Dickinson) and 0.05% w/v Tween 80 (7H9-Tw-OADC) under aerobic conditions. Bacterial growth was measured by OD590 after 5 days of incubation at 37°C. Curves were fitted using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. MIC90 was defined as the minimum concentration required to inhibit growth of M. tuberculosis by 90%.

HepG2 cytotoxicity.

Cytotoxicity was assessed using the HepG2 cell line under replicating conditions.[17] HepG2 cells were grown in DMEM, GlutaMAX™ (Invitrogen), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1X penicillin-streptomycin solution (100 U/mL) using either glucose or galactose as carbon source. Cells were incubated with compounds for 2 days at 37 °C (final DMSO concentration of 1%), 5% CO2. CellTiter-Glo® Reagent (Promega) was added and relative luminescent units (RLU) measured to assess cell viability. Inhibition curves were fitted using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. IC50 is the concentration required to reduce cell viability after 2 days by 50%.[33]

NMR-based Water-LOGSY (Water-Ligand Observed via Gradient Spectroscopy) and Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) assays were carried out according to published methods.[26, 27] A typical sample solution with protein present contained 44.2 μM of MbtA with ligand at a final concentration of 0.75 mM in 16.5:83.5 / DMSO-d6:H2O-D2O (H2O:D2O/90:10) in a final sample volume of 650 μL. NMR experiments were carried out using a Jeol JNM-ECZR 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a ROYAL probe operating at a proton resonance frequency of 600.13 MHz. Standard 1D 1H NMR spectra acquired on protein-free and protein-loaded ligand samples were acquired with presaturation of the water signal using a composite read pulse and crusher gradients to yield clean solvent suppression according to the Jeol pulse program ROBUST. Data were acquired over a frequency width equivalent to 15.0 ppm into 16K data points (acquisition time = 1.44 s) for each of typically 16 (ligand only) or 1024 (with added protein) transients using a presaturation delay of 5.0 s between transients. The offset was centred at the largest solvent signal. Saturation Transfer Difference NMR spectra were prepared from data acquired using the Jeol pulse program STD. Gaussian-shaped saturation pulses of 60 ms duration cycled over a total duration of 6.0 s were applied interleaved both on and off resonance. The total recycle delay was set to 7.0 s. Difference spectra were generated by subtraction of the off-resonance reference data from the on-resonance irradiation data. In STD experiments, the irradiation frequencies corresponded to the following chemical shifts: Off Resonance [Control] = −200.00 ppm (minus two hundred parts per million); On Resonance [Protein Irradiation] = 0.7 ppm (zero point seven parts per million). Water-LOGSY NMR spectra were generated using the Jeol pulse program Water-LOGSY_ES. Water suppression was achieved using excitation sculpting with gradients. A mixing time of 1.6 s was used to allow for magnetization transfer build-up from solvent to ligand in the presence or absence of protein.

Fluorescent-based Thermal Shift Assay (FTSA) was carried out using a 96-well plate format on a BioRad CFX Connect RT-PCR instrument. Each well contained 3 μg of purified MbtA, 5 nL 5000X Sypro Orange (Invitrogen) in 10 μL volume (buffer: 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl) with a resultant protein concentration of 5.17 μM. The ligand final concentrations were 10 μM in 1% DMSO. Following the addition of protein and compounds, the PCR plates were sealed with optical seal, shaken, and centrifuged for 30 min. Thermal scanning (10 to 90°C with a heating rate of 1°C/ min increment) was performed using a real-time PCR setup and fluorescence intensity was measured after every 10 seconds. Curve fitting, melting temperature calculation and report generation on the raw FTS data were performed using software developed by Biorad Laboratories and adapted by us. The screening of the 3200 compounds was carried out in an individual fashion with each well containing only one compound. Compounds exhibiting positive Tm shift >3°C were considered as hits.

Modelling studies.

The MbtA protein structure was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB Ref: 5KEI).[18] The protein pdb file was opened in Autodock Tools (ADT), [35] the solvent and ions were removed and the resulting structure was saved as a pdbqt file for use in Autodock Vina. [36] The small molecule ligands were prepared by constructing the 2D structures in ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0 which were saved in sdf format. The 2D representations were converted into 3D structures using ChemBio3D Ultra 14.0 and energy minimised using the integrated MM2 and GAMESS AM1 protocols with default settings. The compounds were saved in mol2 file format and converted to the pdbqt format using Openbabel 2.3.2.[37] Autodock Vina was run using an Exhaustiveness setting of 40 and a binding site box centred on the nucleotide binding pocket (by analogy with the related structure PDB Ref: 1MDB)[38] that was 24 × 24 × 24 Å in size. All other parameters were set to their default values. The lowest energy conformation of each docked ligand was extracted from the results file using a custom script and analysed in Pymol (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7 Schrödinger, LLC).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Aaron Korkegian, Yulia Ovechkina, Megha Gupta, Douglas Joerss, Lindsay Flint and Gary Litherland (FTSA set-up) for technical assistance. This project has been funded in part with the University of the West of Scotland PhD studentship scheme (L. F.) and Federal funds from the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract Nos.: HHSN272201200025C and HHSN272201700059C. S.B. is a Cipla distinguished Fellow and would like to acknowledge a Global Challenges Research Fund support.

References:

- [1].World Health Organization ed., 2018. Global tuberculosis report 2017. World Health Organization; https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- [2].European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe 2017. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Dye C, Lancet 2006, 367, 938–940; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dheda K, Gumbo T, Maartens G, et al. , Lancet Respir Med 2017, 5, 291–360. [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Fang Z, Sampson SL, Warren RM, Gey van Pittius NC, Newton-Foot M, Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2015, 95, 123–130; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ratledge C, Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004, 84, 110–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lamb AL, Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1854, 1054–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rodriguez GM, Trends Microbiol 2006, 14, 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Barclay R, Ewing DF, Ratledge C, J. Bacteriol 1985, 164, 896–903; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ratledge C, Ewing M, Microbiology 1996, 142, 2207–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Barry CE 3rd, J. Bacteriol 1999, 181, 4443–4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. , Nature 1998, 393, 537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Quadri LE, Sello J, Keating TA, Weinreb PH, Walsh CT, Chem Biol 1998, 5, 631–645; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McMahon MD, Rush JS, Thomas MG, J Bacteriol 2012, 194, 2809–2818; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chavadi SS, Stirrett KL, Edupuganti UR, Vergnolle O, Sadhanandan G, Marchiano E, Martin C, Qiu WG, Soll CE, Quadri LE, J Bacteriol 2011, 193, 5905–5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Su H, Zhu Y, Barry CE 3rd, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 1252–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lun S, Guo H, Adamson J, Cisar JS, Davis TD, Chavadi SS, Warren JD, Quadri LE, Tan DS, Bishai WR, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 5138–5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Reddy PV, Puri RV, Chauhan P, Kar R, Rohilla A, Khera A, Tyagi AK, J Infect Dis 2013, 208, 1255–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Nelson KM, Viswanathan K, Dawadi S, Duckworth BP, Boshoff HI, Barry CE 3rd, Aldrich CC, J Med Chem 2015, 58, 5459–5475; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dawadi S, Boshoff HIM, Park SW, Schnappinger D, Aldrich CC ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2018, 9, 386–391; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Somu RV, Wilson DJ, Bennett EM, Boshoff HI, Celia L, Beck BJ, Barry CE 3rd, Aldrich CC, J Med Chem 2006, 49, 7623–7635; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LE, Nat Chem Biol 2005, 1, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Duckworth BP, Nelson KM, Aldrich CC, Curr Top Med Chem 2012, 12, 766–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bhakta S, Mol Biol 2013, 2, e108. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ollinger J, Bailey MA, Moraski GC, et al. PloS one 2013, 8, e60531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Vergnolle O, Xu H, Tufariello JM, Favrot L, Malek AA, Jacobs WR Jr., Blanchard JS, J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 22315–22326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Baugh L, Phan I, Begley DW, et al. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fedorov O, Niesen FH, Knapp S, Methods Mol Biol 2012, 795, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McDonnell PA, Yanchunas J, Newitt JA, et al. , Anal Biochem 2009, 392, 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Moreau C, Kirchberger T, Swarbrick JM, Bartlett SJ, Fliegert R, Yorgan T, Bauche A, Harneit A, Guse AH, Potter BVL, J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 10079–10102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Marroquin LD, Hynes J, Dykens JA, Jamieson JD and Will Y, Toxicol. Sci, 2007, 97, 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Meyer B, Peters T, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2003, 42, 864–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manning AJ, Ovechkina Y, McGillivray A, Flint L, Roberts DM, Parish T, Methods 2017, 127, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ratledge C, Tuberculosis 2004, 84(1–2),110–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pandey SD, Choudhury M, Yousuf S, Wheeler PR, Gordon SV, Ranjan A, Sritharan M J. Bacteriol 2014, 196, 1853–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Meyer B, Peters T, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2003, 42, 864–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dalvit C, Fogliatto GP, Stewart A, Veronesi M and Stockman B, J. Biomol. NMR 2001, 21, 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cooper CB J Med Chem, 2013, 56, 7755–7760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) Myler PJ, Stacy R, Stewart L, Staker BL, Van Voorhis WC, Varani G, Buchko GW, Infect Disord Drug Targets 2009, 9, 493–506; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stacy R, Begley DW, Phan I, Staker BL, Van Voorhis WC, Varani G, Buchko GW, Stewart LJ, Myler PJ, Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2011, 67, 979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].a) Bryan CM, Bhandari J, Napuli AJ, Leibly DJ, Choi R, Kelley A, Van Voorhis WC, Edwards TE, Stewart LJ, Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2011, 67, 1010–1014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Choi R, Kelley A, Leibly D, Hewitt SN, Napuli A, Van Voorhis W, Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2011, 67, 998–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Aslanidis C, de Jong PJ, Nucleic Acids Res 1990, 18, 6069–6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Studier FW, Protein Expr Purif 2005, 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zuniga ES, Korkegian A, Mullen S, et al. Bioorg Med Chem 2017, 25, 3922–3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dalvit C, Fogliatto GP, Stewart A, Veronesi M and Stockman B, J. Biomol. NMR 2001, 21, 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, et al. J Comput Chem 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Trott O, Olson AJ J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].O’Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, et al. J. Cheminf 2011, 3:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].May JJ, Kessler N, Marahiel MA, Stubbs MT Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99, 12120–12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.