Introduction

The normal vascular endothelium functions as an integral barrier, separating blood from highly reactive elements of the subendothelium, such as collagen and tissue factor. Disruption of the vessel wall by biochemical or physical stimuli to the cerebral, coronary or peripheral arteries results in rapid activation of the endothelium, platelet aggregation for primary and secondary hemostasis and leukocyte accumulation. Secondary release of nucleotides is a potent promoter of thrombosis and inflammation. The endothelium maintains vascular integrity and blood fluidity by acting as an anticoagulant, suppressing platelet activation, promoting fibrinolysis and a quiescent state. This occurs by endogenous thromboregulatory mechanisms including release of eicosanoids, generation of nitric oxide, heparan sulfate expression and catabolism of the purinergic nucleotides adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adenosine monophosphate (AMP) (Figure 1). Nucleotides are constitutively released from vascular cells at low rates, which increase when cells are injured or stressed. These nucleotides function as potent, paracrine signaling molecules to activate pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory programs in the vasculature by exerting purinergic receptor-mediated signaling on platelets, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and leukocytes.

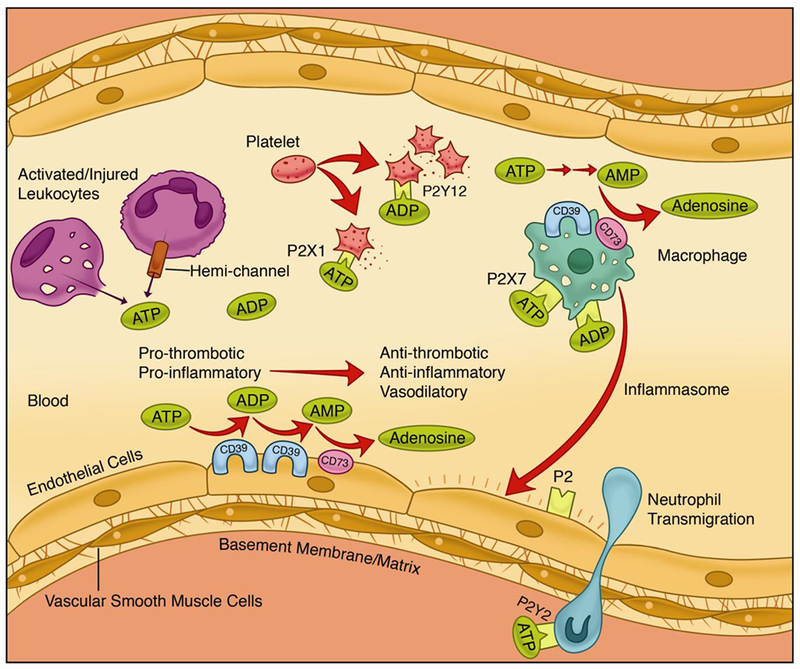

Figure 1.

The CD39/CD73 pathway modulates vascular inflammation and thrombosis in response to injury. Nucleotides released during cell activation/injury bind to P2 receptors to activate thrombo-inflammatory programs in the vasculature by binding to receptors on the endothelium, platelets and leukocytes. Endothelial and circulating leukocytes express the catabolic machinery to convert ATP/ADP into adenosine to quench the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic signals and exert a potent, protective vascular effect. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP); adenosine diphosphate (ADP); adenosine monophosphoate (ADP).

The purinergic system is evolutionarily selected to maintain vascular integrity. Nucleotide concentrations increase in the extracellular microenvironment following platelet and endothelial cell activation, leukocyte degranulation or the apoptosis or necrosis of vascular and inflammatory cells. Nucleotide release occurs by cell lysis and non-lytic mechanisms. Non-lytic processes include exocytosis of nucleotide-containing vesicles and nucleotide-permeable channels which can release nucleotides upon cellular perturbation short of cell lysis [1]. When released, nucleotides have immediate effects in the local environment and are rapidly inactivated by degradation. The nucleotides and their metabolites function as ligands for P2 and adenosine receptors expressed on the surface of vascular cells. Binding of nucleotides to these purinergic receptors mediates the thrombo- and inflammo-modulatory effects of purines. P2 receptors have been classified into two subfamilies, the ionotropic P2X (1-7) and metabotropic P2Y (1,2,4,6,11-14) receptors [2] that effect downstream signaling pathways involved in cell metabolism, vasodilation, leukocyte activation and migration [3].

Ectonucleotidases in the vasculature moderate extracellular nucleotide levels, thereby modulating P2 and adenosine receptor function. CD39 (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1), a transmembrane protein first identified on B lymphoid cells with potent nucleotidase activity is the dominant ectonucleotidase in the vasculature [4, 5]. This ectonucleotidase is located on the endothelium, circulating blood cells and smooth muscle cells [6, 7]. CD39 hydrolyzes phosphate groups on nucleotides, converting ATP and ADP to AMP. A related ectonucleotidase, CD73 (ecto-5′-nucleotidase), dephosphorylates AMP into adenosine, a potent anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic and vasodilatory molecule.

Vascular inflammation and thrombosis underlie several common clinical diseases including atherosclerosis, stroke, myocardial infarction, ischemia-reperfusion injury and systemic inflammatory conditions such as sepsis and auto-immune disease. This review will focus on the role of CD39 and its ability to regulate purinergic signaling in modulating vascular inflammation and thrombosis.

CD39 structure and function

CD39 is an evolutionarily conserved, integral membrane protein that hydrolyzes both ATP and ADP in a cation-dependent manner to generate AMP. Human CD39 is a 510-amino acid membrane protein with two transmembrane domains, a small cytoplasmic domain that contains the NH2 and COOH-terminal segments and an extracellular hydrophobic domain. The enzymatically active extracellular hydrophobic domain contains five apyrase-conserved regions which are responsible for nucleotide catabolism [5]. The protein is 57-100 kD in size and undergoes significant post-translational modification including glycosylation, palmitoylation and ubiquitination [8–10]. CD39 is inactive in the cytoplasmic compartment until localization to the cell surface where it becomes catalytically active. Targeting to the cell surface occurs by lipid raft-dependent mechanisms, such as caveolae [11]. Interestingly, CD73 has also been observed in cell surface lipid rafts in different cell types [12], suggesting the possibility of a colocalization with CD39 for efficient generation of adenosine from ATP and ADP substrates although this remains to be completely investigated.

Regulation of CD39 expression

The molecular mechanisms that regulate CD39 are largely unknown and the subject of active investigation in our lab and others. Work from our group identified cyclic AMP (cAMP), an intracellular second messenger signaling molecule, as a potent, positive regulator of CD39 expression in macrophages [13]. Mechanistically, we determined that treatment with cAMP leads to dimerization of cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB). CREB dimers subsequently associate with other cofactors, p300 and CREB-binding protein, to activate a cAMP-reponse element (CRE) in the CD39 promoter and thereby stimulate transcription. A similar paradigm of increased CD39 expression was observed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) treated with cAMP agonists [10]. Intracellular cAMP is rapidly degraded by phosphodiesterases, and several phosphodiesterase inhibitors have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration including cilostazol and milrinone. These two phosphodiesterase type 3 (PDE3) inhibitors are approved for use in the treatment of peripheral artery disease and decompensated heart failure, respectively. We demonstrated that higher intracellular cAMP levels from PDE3 inhibition with either cilostazol or milrinone did not affect CD39 transcript levels, but did increase CD39 protein expression and ATPase/ADPase activity. We identified a novel mechanism by which CD39 undergoes post-translational modification, with diminished ubiquitination driven by PDE3 inhibition, an area of continued investigation in our laboratory. In addition to ubiquitination, CD39 is also modified by palmitoylation and is heavily glycosylated with six known N-glycosylation sites, essential for protein folding and membrane targeting [8, 9].

Work by Plow and colleagues suggests that CD39 and CD73 on the cell membrane may be recycled by endocytosis. In this study, perturbations in the interaction of a cytoskeletal protein, kindlin-2 with clathrin heavy chain, a central regulator of surface macromolecule endocytosis increased expression of both CD39 and CD73 at the endothelial cell surface [14].

A recent study identified Stat3 and Gfi-1 as positive transcriptional regulators of CD39 and CD73 expression in innate immune cells following exposure to interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TGF-beta, respectively. Enhanced ectonucleotidase expression led to generation of adenosine and suppression of activated CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell effector functions [15]. Indeed, several stress-induced conditions have been shown to decrease CD39 expression including pro-inflammatory cytokines: interleukin-17 (IL-17) and TNF-alpha [16]; endothelial cell activation and oxidative stress [17] and hypoxia [18]. Each of these perturbations lead to diminished ability to clear nucleotides and maintain vascular homeostasis.

Hypoxia is a potent activator of the endothelium, rapidly initiating a cascade of biosynthetic and stress response processes [19, 20] including expression of cell adhesion molecules, prothrombotic factors, generation of reactive oxygen species and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. An important study by Eltzschig et al. demonstrated that endothelial CD39 expression could be induced in vitro by exposure to hypoxia [18]. The interaction of the hypoxia-inducible factor, Sp1 and a hypoxia-response element on the CD39 promoter initiated CD39 mRNA transcription [18].

Vascular thrombosis

Platelet aggregation is a primary process in thrombus formation, accompanied by tissue factor deposition and generation of a fibrin meshwork to stabilize the platelet thrombus. Initial platelet accumulation is rapid, followed by a decrease in thrombus size, with a degree of platelet disaggregation and thrombus stabilization. On activation, platelet granules fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing their cargo into the extracellular environment, including vWF and P-selectin from alpha granules, and ADP from dense granules. While these biochemical signals herald a propagating thrombus, the mechanism underlying the observed early decrease in platelet mass is unclear [3]. Microparticles, submicron-sized vesicles released from activated cells, contain tissue factor, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and other thrombomodulatory elements that mediate interactions between platelets, leukocytes and the endothelium [21]. CD39 has been identified on human and murine microparticles and has been proposed as a possible contributor to platelet disaggregation by dissipating extracellular ADP to regulate thrombus size [3, 21,22]. Indeed, microparticles from mice lacking CD39 induce a pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory response from endothelial cells in vitro with enhanced expression of the cell adhesion molecules, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and release of tumor necrosis factor-α, von Willebrand factor accompanied by diminished anti-inflammatory mediators [21]. A recent study by Visovatti et al in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH), a disease characterized by high vascular resistance, microvascular thrombosis and perivascular inflammation compared circulating microparticles from patients with IPAH with healthy controls. This study found elevated, functional CD39 on microparticles in IPAH when compared with healthy patients. The authors concluded that additional work was needed to elucidate whether CD39 could be implicated in the pathogenesis of IPAH or as a compensatory response [22].

Interestingly, mice globally lacking CD39 have paradoxically inhibited platelet function due to purinergic type P2Y1 receptor desensitization from excess nucleotide stimulation. Platelet hypofunction was seen with inhibited microthrombi formation in response to free radical injury, accompanied by prolonged tail bleeding times in vivo. Platelet aggregation with multiple platelet agonists was also inhibited in vitro and completely rescued by apyrase pre-treatment [23, 24], Conversely, mice overexpressing human CD39 are resistant to oxidant injury-mediated arterial thrombosis, likely due to attenuated activation of the platelet fibrinogen receptor, glycoprotein αIIb/β3 [25].

Stroke

Investigations of cerebrovascular thrombosis or stroke elucidated the role of a primary, occlusive arterial thrombus followed by progressive, microvascular thrombosis with platelet and fibrin accumulation, resulting in cerebral hypoperfusion and injury. Mice genetically deficient for CD39 have a latent, prothrombotic phenotype with enhanced microvascular platelet and fibrin deposition downstream of cerebrovascular occlusion and larger infarct areas. Treatment with a soluble, engineered form of CD39, or plant apyrase which phosphohydrolyzes nucleotides, rescued this phenotype by disaggregating platelets during thrombus formation without affecting primary hemostasis to maintain vascular integrity as well as reduced leukocyte recruitment [26, 23]. Mice lacking CD39 have also been shown to have marked fibrin deposition in pulmonary and cardiac tissues under baseline conditions [24].

Atherosclerosis and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion

Inflammation and thrombosis are central processes in the development of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease and subsequent myocardial infarction. As a critical modulator of purinergic signaling, CD39 plays a vital role in myocardial infarction. In a mouse model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, CD39 deficiency resulted in increased myocardial ATP accumulation and adenosine deficiency with an increased susceptibility to myocardial injury [18]. Conversely, overexpression of CD39 induced protection from myocardial infarction as measured by infarct size in mouse and pig models of ischemia-reperfusion injury [27, 28] and preserved cardiac allograft function with diminished platelet aggregation [29]. CD39 overexpression has also been shown to mitigate hypertension in preeclampsia [30] and reduce renal ischemia-reperfusion injury [31]. Taken together, these studies elucidated a critical role for CD39 in protection from ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Interestingly, a small cohort of coronary atherectomy samples from patients with stable and unstable angina showed lower CD39 immuno-positivity in patients with unstable angina or coronary thrombus formation than in those with stable angina [32]. It remains to be determined if the increase in CD39 immunoreactivity is related to higher CD39 expression on resident, vascular cells or an increase in leukocytes bearing CD39. In an arterial wire injury model, CD39 appeared to contribute to neointimal hyperplasia as mice lacking functional CD39 had reduced smooth muscle cell migration and were protected from neointima formation [7]. More research is needed to shed light on the role of CD39 in regulating atherosclerosis and neointima.

Over the past two decades, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statin) have been extensively studied for their pleiotropic effects on vascular cells with anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects. Interestingly, treatment with statin drugs in vitro has been shown to increase endothelial CD39 expression [16] with a parallel reduction in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, reinforcing the need for further investigation into the role of CD39 therapeusis [33].

However, platelet reactivity and aggregation alone are inadequate to account for the enhanced response to vascular injury seen in mice lacking CD39, as seen in work by our lab and others in studies of stroke [26, 23], myocardial ischemia-reperfusion [34], pulmonary hypertension [22], and renal [31] and hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury [35].

Vascular Inflammation

In addition to their effects on thrombosis, nucleotides are potent inflammatory mediators, triggering autocrine and paracrine purinergic signaling pathways that regulate cell-cell interaction and leukocyte migration [36]. Under homeostatic conditions in humans, CD39 is found on the majority of monocytes, neutrophils, and B-lymphocytes [6]. A minority of T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells express CD39 in healthy humans [6]. Under homeostatic conditions, the endothelium is the predominant source of CD39, while amongst leukocytes, CD39 is most densely expressed on monocytes and B-lymphocytes [6, 4]. Under conditions of stress, specifically when there is a robust inflammatory response, leukocyte CD39 becomes the main source of ectonucleotidase activity [4]. CD39 expression may also increase on endothelial cells and parenchymal cells in response to an insult such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, or on vascular smooth muscle cells following arterial balloon injury [34, 7].

Since CD39 modulates extracellular purine concentrations but is found on the surface of leukocytes which in turn migrate in response to these gradients, CD39 can be viewed as an auto-regulator of leukocyte accumulation. In work from our laboratory, neutrophil and macrophage influx into the brain were significantly enhanced in the absence of CD39 following induction of stroke. We identified a novel mechanism by which leukocyte influx is self-regulated by CD39-mediated metabolism of local nucleotides, resulting in suppression of αMβ2-integrin (MAC-1) expression driven by the P2X7 receptor [23].

CD39 and neutrophils

CD39 is expressed on neutrophils under resting conditions [6]. After tissue injury, neutrophils home to damaged tissue, increasing the local concentration of CD39. Through purinergic signaling, CD39 regulates neutrophil migration via paracrine and autocrine signaling. CD39 levels increase in response to hypoxia, an inflammatory stimulus, with CD39 expression tempering the innate immune response via downstream adenosine production [37]. In this model, endogenous intravascular adenosine production attenuated neutrophil adhesion after inflammatory stimuli through neutrophil adenosine A2A and A2B receptors [37]. In the absence of CD39, increased trafficking of neutrophils to injured tissue was observed, due in part to loss of normal endothelial barrier/capillary leakage observed in mice lacking CD39 [38].

Neutrophils also use ATP and adenosine as autocrine signals for orientation and migration [36]. Once stimulated, neutrophils mobilize CD39 to the leading edge of the polarized cell [39]. ATP is also released from the leading edge of the neutrophil cell surface. This ATP is then catabolized by CD39 present in close proximity to the leading edge. This then results in local adenosine production and stimulates A3 receptors to promote cellular migration [36].

CD39 plays an important role in modulating neutrophil phenotype. CD39 on the surface of neutrophils hydrolyzes ATP and prevents it from activating the P2Y2 receptor [40]. In the absence of CD39, this process goes unchecked and leads to ATP stimulation of P2Y2 receptors and increased neutrophil interleukin-8 (IL-8) production [40]. Given that IL-8 is an important chemokine for leukocyte recruitment, this adds to the influence of CD39 in dampening the normal immune response.

CD39 may also influence the timing of neutrophil accumulation after tissue injury. In a study of acute lung injury, extracellular ATP was found to modulate the late phase of neutrophil recruitment, with extracellular ATP peaking 3 days after tissue injury, an effect which was abrogated by treatment with soluble CD39 [41].

CD39 and macrophage/monocytes

CD39 is expressed on monocytes and macrophages, classic examples of myeloid inflammatory cells. Immunosuppressive macrophages in mice have been found to have higher CD39 expression on their surface [42]. It is unclear whether CD39 expression on macrophages is a cause or an effect of the cellular phenotype. A study demonstrating that adenosine promotes the immunosuppressive macrophage phenotype suggests that CD39 could contribute to this phenotype by generation of substrates for extracellular adenosine production [43]. Activation of A2Band A2A adenosine receptors was found to be important for expression of an immunosuppressive macrophage phenotype. Observations made in humans with sepsis showed a switch in macrophage phenotype from inflammatory to immunosuppressive, suggesting a role for the latter in protection from lethal sepsis, although the mechanism has not been elucidated [44]. Another recent study by Cohen et al. explored whether CD39 on macrophages could modulate this shift. This study demonstrated that TLR stimulation of macrophages using in vivo model of sterile inflammation with lipopolysaccharide injection activates auto-regulation of macrophage activation by CD39-mediated catabolism of ATP and generation of adenosine to limit the inflammatory response [45]. CD39 plays a critical role in tempering the inflammatory signals released by macrophages. Activated CD39-null macrophages exposed to ATP are more susceptible to cell death, and release more interleukin-18 (IL-18) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) than cells with a normal complement of CD39. The enhanced IL-1β release is facilitated by P2X7 receptor-dependent signaling downstream of pro-IL-1β synthesis rather than CD39-mediated differences in mRNA transcription or translation [46].

CD39 and lymphocytes

CD39 is expressed on T- and B-cell lymphocytes. Of late, much attention has been focused on the role of CD39 contributing to the anti-inflammatory properties of regulatory (Treg) CD4+ T cells. CD39 is expressed on Treg cells, and expression has been found to be driven by the Treg-specific transcription factor Foxp3 [47]. The immune modulating capabilities of Tregs have been attributed in part to CD39 expression on Tregs, with resulting dissipation of ATP to adenosine [48]. This has dual effects as stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor on activated T effector cells results in immunosuppression [48]. CD39 expression on Tregs also averts ATP-induced inflammatory cell accumulation and maturation of dendritic cells [47].

A subset of T cells exists that do not express FoxP3, but which do express CD39 [49, 50]. These T cells have a distinct cellular phenotype termed memory effector, and they do not have an immunosuppressive phenotype. Instead, cell surface CD39 appears to protect these T cells from ATP-induced apoptosis [50]. These cells express higher levels of T helper cell specific cytokines as well as inflammatory cytokines, and rapidly release these factors upon stimulation [50]. Interestingly, T cells of both groups (FoxP3+ CD39+ and FoxP3-CD39+) have been shown to be co-expressed at the site of inflammatory arthritis, highlighting the complexity of the T-cell mediated immune response and the role of CD39 in tempering and possibly propagating the inflammatory response simultaneously [51]. IL-6 may alter the balance of these competing cell types. Recently it was shown that blocking IL-6 increased the frequency of CD39+ Treg cells without changing the frequency of effector T cells, thereby altering the balance between the two [52].

CD39 and dendritic cells

Dendritic cells play a vital role in the immune system, serving as efficient antigen-presenting cells and initiating T cell activation. CD39 is present on the surface of dendritic cells, and extracellular ATP has been shown to affect the activation status of dendritic cells [53–55]. Langerhans cells are epithelial dendritic cells which demonstrated impaired antigen presenting capacity in the absence of CD39, attributed to elevated ATP concentrations and P2-receptor desensitization [56].

Conclusion

Extracellular purinergic-mediated cell activation has significant implications in thrombosis, the inflammatory response, tissue remodeling and repair in vascular injury. CD39 is a critical mediator in the pathway for extracellular nucleotide catabolism and adenosine generation to regulate vascular inflammation and thrombosis.

In multiple models of inflammation and thrombosis, CD39-deficient mice have persistent endothelial, platelet and leukocyte activation, with elevated peri-cellular nucleotide accumulation and unchecked nucleotide receptor signaling contributing to platelet and leukocyte accumulation, with detrimental effects on vascular and tissue repair. CD39 on microparticles may also contribute to IPAH pathogenesis as seen in recent human studies. CD39 represents a built-in, molecular brake on endothelial and immune cells and exerts tight regulation of vascular inflammation and thrombosis at sites of injury. Further investigation and enhanced understanding of the molecular and cellular pathways of purinergic signaling might result in new therapeutics for vascular thombo-inflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH 5T32HL007853-17, the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute, and the J. Griswold Ruth, M.D., and Margery Hopkins Ruth Professorship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Yogendra M. Kanthi, Nadia R. Sutton, and David J. Pinsky declare that they no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Schenk U, Westendorf AM, Radaelli E, Casati A, Ferro M, Fumagalli M et al. Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through pannexin-1 hemichannels. Science signaling. 2008;l(39):ra6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kukulski F, Levesque SA, Sevigny J. Impact of ectoenzymes on p2 and pi receptor signaling. Advances in pharmacology. 2011;61:263–99. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deaglio S, Robson SC. Ectonucleotidases as regulators of purinergic signaling in thrombosis, inflammation, and immunity. Advances in pharmacology. 2011;61:301–32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonner F, Borg N, Burghoff S, Schrader J. Resident cardiac immune cells and expression of the ectonucleotidase enzymes CD39 and CD73 after ischemic injury. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e34730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maliszewski CR, Delespesse GJ, Schoenborn MA, Armitage RJ, Fanslow WC, Nakajima T et al. The CD39 lymphoid cell activation antigen. Molecular cloning and structural characterization. J Immunol. 1994; 153(8) :3574–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulte ED, Broekman MJ, Olson KE, Drosopoulos JH, Kizer JR, Islam N et al. CD39/NTPDase-l activity and expression in normal leukocytes. Thrombosis research. 2007;121(3):309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behdad A, Sun X, Khalpey Z, Enjyoji K, Wink M, Wu Y et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 (ENTPD1) is required for neointimal formation in mice. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5(3):335–42. doi: 10.1007/sll302-009-9158-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith TM, Kirley TL. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a human brain ecto-apyrase related to both the ecto-ATPases and CD39 ecto-apyrasesl. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1998;1386(l):65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koziak K, Kaczmarek E, Kittel A, Sevigny J, Blusztajn JK, Schulte Am Esch J, 2nd et al. Palmitoylation targets CD39/endothelial ATP diphosphohydrolase to caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(3):2057–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **10.Baek AE, Kanthi Y, Sutton NR, Liao H, Pinsky DJ. Regulation of ecto-apyrase CD39 (ENTPD1) expression by phosphodiesterase III (PDE3). FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2013;27(ll):4419–28. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-234625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This Is an important study demonstrating pharmocologic modulation ofCD39 expression with existing drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Use of the PDE3 inhibitor family of pharmaceuticals represents a novel approach to harness CD39 expression.

- 11.Papanikolaou A, Papafotika A, Murphy C, Papamarcaki T, Tsolas O, Drab M et al. Cholesterol-dependent lipid assemblies regulate the activity of the ecto-nucleotidase CD39. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(28):26406–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strohmeier GR, Lencer Wl, Patapoff TW, Thompson LF, Carlson SL, Moe SJ et al. Surface expression, polarization, and functional significance of CD73 in human intestinal epithelia. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(11):2588–601. doi: 10.1172/JCI119447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao H, Hyman MC, Baek AE, Fukase K, Pinsky DJ. cAMP/CREB-mediated transcriptional regulation of ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (CD39) expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285( 19): 14791–805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pluskota E, Ma Y, Bledzka KM, Bialkowska K, Soloviev DA, Szpak D et al. Kindlin-2 regulates hemostasis by controlling endothelial cell-surface expression of ADP/AMP catabolic enzymes via a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2013;122(14):2491–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **15.Chalmin F, Mignot G, Bruchard M, Chevriaux A, Vegran F, Hichami A et al. Stat3 and Gfi-1 transcription factors control Th17 cell immunosuppressive activity via the regulation of ectonucleotidase expression. Immunity. 2012;36(3):362–73. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This Is an Important study that implicates CD39 in the mechanism of immune modulation by Th17 cells. It further idenifies direct and indirect transcriptional signals that regulate CD39 expression under cellular stress.

- 16.Hot A, Lavocat F, Lenief V, Miossec P. Simvastatin inhibits the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic effects of IL-17 and TNF-alpha on endothelial cells. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2013;72(5):754–60. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robson SC, Kaczmarek E, Siegel JB, Candinas D, Koziak K, Millan M et al. Loss of ATP diphosphohydrolase activity with endothelial cell activation. J Exp Med. 1997;185(1):153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eltzschig HK, Kohler D, Eckle T, Kong T, Robson SC, Colgan SP. Central role of Sp1-regulated CD39 in hypoxia/ischemia protection. Blood. 2009;113(1):224–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa S, Clauss M, Kuwabara K, Shreeniwas R, Butura C, Koga S et al. Hypoxia induces endothelial cell synthesis of membrane-associated proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(21):9897–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manalo DJ, Rowan A, Lavoie T, Natarajan L, Kelly BD, Ye SQ et al. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood. 2005;105(2):659–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banz Y, Beldi G, Wu Y, Atkinson B, Usheva A, Robson SC. CD39 is incorporated into plasma microparticles where it maintains functional properties and impacts endothelial activation. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(4):627–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Visovatti SH, Hyman MC, Bouis D, Neubig R, McLaughlin VV, Pinsky DJ. Increased CD39 nucleotidase activity on microparticles from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e40829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an important study that demonstrates a potential role for CD39 in pulmonary arterial hypertension, a devastating disease with poor prognosis and limited therapeutics.

- 23.Hyman MC, Petrovic-Djergovic D, Visovatti SH, Liao H, Yanamadala S, Bouis D et al. Self-regulation of inflammatory cell trafficking in mice by the leukocyte surface apyrase CD39. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(5):1136–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI36433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enjyoji K, Sevigny J, Lin Y, Frenette PS, Christie PD, Esch JS 2nd, et al. Targeted disruption of cd39/ATP diphosphohydrolase results in disordered hemostasis and thromboregulation. Nat Med. 1999;5(9):1010–7. doi: 10.1038/12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huttinger ZM, Milks MW, Nickoli MS, Aurand WL, Long LC, Wheeler DG et al. Ectonucleotide triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (CD39) mediates resistance to occlusive arterial thrombus formation after vascular injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(1):322–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinsky DJ, Broekman MJ, Peschon JJ, Stocking KL, Fujita T, Ramasamy R et al. Elucidation of the thromboregulatory role of CD39/ectoapyrase in the ischemic brain. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(8):1031–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI10649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheeler DG, Joseph ME, Mahamud SD, Aurand WL, Mohler PJ, Pompili VJ et al. Transgenic swine: expression of human CD39 protects against myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52(5):958–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai M, Huttinger ZM, He H, Zhang W, Li F, Goodman LA et al. Transgenic over expression of ectonucleotide triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 protects against murine myocardial ischemic injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51(6):927–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dwyer KM, Robson SC, Nandurkar HH, Campbell DJ, Gock H, Murray-Segal LJ et al. Thromboregulatory manifestations in human CD39 transgenic mice and the implications for thrombotic disease and transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(10):1440–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI19560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McRae JL, Russell PA, Chia JS, Dwyer KM. Overexpression of CD39 protects in a mouse model of preeclampsia. Nephrology. 2013;18(5):351–5. doi: 10.1111/nep.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crikis S, Lu B, Murray-Segal LM, Selan C, Robson SC, D’Apice AJ et al. Transgenic overexpression of CD39 protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion and transplant vascular injury. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2010;10(12):2586–95. doi: 10.UU/j.1600-6143.2010.03257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatakeyama K, Hao H, Imamura T, Ishikawa T, Shibata Y, Fujimura Y et al. Relation of CD39 to plaque instability and thrombus formation in directional atherectomy specimens from patients with stable and unstable angina pectoris. The American journal of cardiology. 2005;95(5):632–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaneider NC, Egger P, Dunzendorfer S, Noris P, Balduini CL, Gritti D et al. Reversal of thrombin-induced deactivation of CD39/ATPDase in endothelial cells by HMG-CoA reductase inhibition: effects on Rho-GTPase and adenosine nucleotide metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(6):894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohler D, Eckle T, Faigle M, Grenz A, Mittelbronn M, Laucher S et al. CD39/ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 provides myocardial protection during cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2007;116(16):1784–94. doi: 10.U61/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida O, Kimura S, Jackson EK, Robson SC, Geller DA, Murase N et al. CD39 expression by hepatic myeloid dendritic cells attenuates inflammation in liver transplant ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):2163–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.26593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314(5806):1792–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eltzschig HK, Thompson LF, Karhausen J, Cotta RJ, Ibla JC, Robson SC et al. Endogenous adenosine produced during hypoxia attenuates neutrophil accumulation: coordination by extracellular nucleotide metabolism. Blood. 2004;104(13):3986–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reutershan J, Vollmer I, Stark S, Wagner R, Ngamsri KC, Eltzschig HK. Adenosine and inflammation: CD39 and CD73 are critical mediators in LPS-induced PMN trafficking into the lungs. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23(2):473–82. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-119701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corriden R, Chen Y, Inoue Y, Beldi G, Robson SC, Insel PA et al. Ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (E-NTPDase1/CD39) regulates neutrophil chemotaxis by hydrolyzing released ATP to adenosine. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(42):28480–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800039200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kukulski F, Bahrami F, Ben Yebdri F, Lecka J, Martin-Satue M, Levesque SA et al. NTPDase1 controls IL-8 production by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2011;187(2):644–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah D, Romero F, Stafstrom W, Duong M, Summer R. Extracellular ATP mediates the late phase of neutrophil recruitment to the lung in murine models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306(2):L152–61. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00229.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanin RF, Braganhol E, Bergamin LS, Campesato LF, Filho AZ, Moreira JC et al. Differential macrophage activation alters the expression profile of NTPDase and ecto-5′-nucleotidase. PloS one. 2012;7(2):e31205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Csoka B, Selmeczy Z, Koscso B, Nemeth ZH, Pacher P, Murray PJ et al. Adenosine promotes alternative macrophage activation via A2A and A2B receptors. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26(1):376–86. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-190934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hotchkiss RS, Coopersmith CM, McDunn JE, Ferguson TA. The sepsis seesaw: tilting toward immunosuppression. Nat Med. 2009;15(5):496–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0509-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen HB, Briggs KT, Marino JP, Ravid K, Robson SC, Mosser DM. TLR stimulation initiates a CD39-based autoregulatory mechanism that limits macrophage inflammatory responses. Blood. 2013;122(11):1935–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levesque SA, Kukulski F, Enjyoji K, Robson SC, Sevigny J. NTPDase1 governs P2X7-dependent functions in murine macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(5):1473–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, Sternjak A, Diamantini A, Giometto R et al. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood. 2007;110(4):1225–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204(6):1257–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dwyer KM, Hanidziar D, Putheti P, Hill PA, Pommey S, McRae JL et al. Expression of CD39 by human peripheral blood CD4+ CD25+ T cells denotes a regulatory memory phenotype. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(11):2410–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Q, Yan J, Putheti P, Wu Y, Sun X, Toxavidis V et al. Isolated CD39 expression on CD4+ T cells denotes both regulatory and memory populations. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9(10):2303–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moncrieffe H, Nistala K, Kamhieh Y, Evans J, Eddaoudi A, Eaton S et al. High expression of the ectonucleotidase CD39 on T cells from the inflamed site identifies two distinct populations, one regulatory and one memory T cell population. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):134–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thiolat A, Semerano L, Pers YM, Biton J, Lemeiter D, Portales P et al. Interleukin-6 Receptor Blockade Enhances CD39+ Regulatory T Cell Development in Rheumatoid Arthritis and in Experimental Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):273–83. doi: 10.1002/art.38246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kansas GS, Wood GS, Tedder TF. Expression, distribution, and biochemistry of human CD39. Role in activation-associated homotypic adhesion of lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1991;146(7):2235–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.la Sala A, Ferrari D, Corinti S, Cavani A, Di Virgilio F, Girolomoni G. Extracellular ATP induces a distorted maturation of dendritic cells and inhibits their capacity to initiate Th1 responses. J Immunol. 2001;166(3):1611–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Idzko M, Dichmann S, Ferrari D, Di Virgilio F, la Sala A, Girolomoni G et al. Nucleotides induce chemotaxis and actin polymerization in immature but not mature human dendritic cells via activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive P2y receptors. Blood. 2002;100(3):925–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizumoto N, Kumamoto T, Robson SC, Sevigny J, Matsue H, Enjyoji K et al. CD39 is the dominant Langerhans cell-associated ecto-NTPDase: modulatory roles in inflammation and immune responsiveness. Nat Med. 2002;8(4):358–65. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]