Abstract

Background

Non-invasive fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) derived from coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) permits hemodynamic evaluation of coronary stenosis and may improve efficiency of assessment in stable chest pain patients. We determined feasibility of FFRCT in the population of acute chest pain patients and assessed the relationship of FFRCT with outcomes of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and revascularization and with plaque characteristics.

Methods

We included 68 patients (mean age 55.8 ± 8.4 years, 71% men) from the ROMICAT II trial who had ≥50% stenosis on coronary CTA or underwent additional non-invasive stress test. We evaluated coronary stenosis and high-risk plaque on coronary CTA.

FFRCT was measured in a core laboratory.

Results

We found correlation between anatomic severity of stenosis and FFRCT ≤0.80 vs. FFRCT >0.80 (severe stenosis 84.8% vs. 15.2%; moderate stenosis 33.3% vs. 66.7%; mild stenosis 33.3% vs. 66.7% patients). Patients with severe stenosis had lower FFRCT values (median 0.64, 25th-75th percentile 0.50–0.75) as compared to patients with moderate (median 0.84, 25th-75th percentile, p<0.001) or mild stenosis (median 0.86, 25th-75th percentile 0.78–0.88, p<0.001). The relative risk of ACS and revascularization in patients with positive FFRCT ≤0.80 was 4.03 (95% CI 1.56–10.36) and 3.50 (95% CI 1.12–10.96), respectively. FFRCT ≤0.80 was associated with the presence of high-risk plaque (odds ratio 3.91, 95% CI 1.55–9.85, p=0.004) after adjustment for stenosis severity.

Conclusion

Abnormal FFRCT was associated with the presence of ACS, coronary revascularization, and high-risk plaque. FFRCT measurements correlated with anatomic severity of stenosis on coronary CTA and were feasible in population of patients with acute chest pain.

Keywords: coronary computed tomography angiography, non-invasive fractional flow reserve, stress test, acute coronary syndrome, risk stratification, non-invasive cardiac testing

Introduction

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) has become a standard method for the evaluation of patients who present to the emergency department (ED) with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).1–3 Coronary CTA permits rapid evaluation of patients with decreased time to diagnosis and discharge as compared to standard work-up with stress testing.1–3 The major strength of coronary CTA is its high negative predictive value for the exclusion of significant coronary stenosis and ACS. However, the positive predictive value, especially in patients with intermediate stenosis, is only moderate. In patients with suspected ACS in the ED, this may result in higher rates of invasive coronary angiography (ICA) and coronary revascularization among patients who undergo coronary CTA as compared to stress testing.1–3

Supplemental analyses of coronary CTA datasets, such as the assessment of coronary plaque, first-pass perfusion and resting wall motion abnormalities, have been proposed to improve specificity and positive predictive value of the test for stenosis and ACS.4–6 More recently, non-invasive fractional flow reserve calculation from coronary CTA (FFRCT) has been developed. Using computational fluid dynamics, FFRCT can provide accurate assessment of fractional flow reserve with standard coronary CTA acquisition and no need for adenosine infusion. The measurements of FFRCT correlated closely with invasive FFR measurements.7,8 The evaluation of hemodynamic significance is important as there is frequent discordance between anatomic severity of stenosis and its hemodynamic significance.9,10 Furthermore, coronary revascularization guided by the hemodynamic assessment with invasive FFR lead to improved outcomes as compared to the anatomic assessment only.11 Management strategy of coronary CTA with FFRCT was demonstrated to be feasible and safe alternative of ICA, with overall lower rate of ICA and equivalent clinical outcomes with lower cost at 1-year followup.12,13 FFRCT was also a better predictor of need for revascularization and future major adverse cardiovascular events when compared to anatomic stenosis detected by coronary CTA.14 There is growing evidence that abnormal FFRCT is not only related to anatomic severity of stenosis, but also to coronary plaque characteristics and burden.15–18

The majority of FFRCT studies has been performed in stable chest pain patients in the outpatient setting. The feasibility and performance of FFRCT in the acute chest pain setting has not been studied. Therefore, we analyzed data from the Rule Out Myocardial Infarction/Ischemia Using Computer Assisted Tomography (ROMICAT) II trial and performed FFRCT measurements in a subgroup of patients to determine the feasibility and performance of the technique in the population of acute chest pain patients in the ED. We also performed advanced coronary plaque analyses to assess the relationship between plaque characteristics and FFRCT and their relation to ACS outcomes.

Methods

Patient population

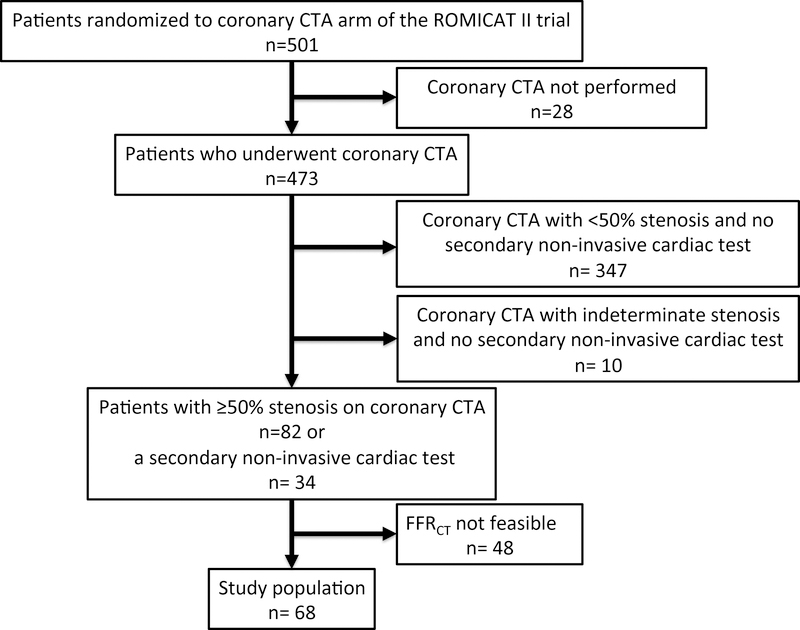

The study population was selected from patients who were enrolled in the ROMICAT II trial, were randomized to the coronary CTA arm of the trial and underwent coronary CTA.2 The ROMICAT II trial enrolled patients with acute chest pain and a low-to-intermediate suspicion for ACS. The local institutional review boards approved the study. In our retrospective study, we evaluated patients who had ≥50% stenosis as determined by the local site reads of coronary CTA or underwent an additional non-invasive cardiac stress test (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Patient inclusions and exclusions.

Coronary CTA

Coronary CTA images were acquired using either retrospectively ECG-gated or prospectively ECG-triggered protocols. The investigators in the study used the scanners from three vendors (Siemens, General Electric, Toshiba) and different scanner generations (64-, 128-, 256-row, and dual source). Local physicians interpreted coronary CTA images and the presence of stenosis was categorized as severe (≥50% stenosis in the left main coronary artery or ≥70% in any coronary artery) or moderate (50%−70% stenosis in any coronary artery). Coronary CTA was deemed indeterminate if the readers were unable to rule out the presence of moderate or severe coronary stenosis.

Computation of FFRCT from coronary CTA

The datasets submitted for the FFRCT analysis met prospectively established inclusion criteria (field of view <250 mm, slice thickness < 1mm, administration of nitroglycerin). The FFRCT implementation employed in this study was performed at a single core laboratory (HeartFlow Inc., Redwood City, California). CTA datasets meeting eligibility criteria were sent to the FFRCT core laboratory. As previously validated, FFRCT core laboratory applied a second set of quantitative criteria to determine whether image quality was adequate for FFRCT analysis based on clear definition of coronary artery lumen and myocardial boundaries.8 CTA datasets with inadequate image quality due to motion artifacts, severe calcium blooming artifacts or excessive image noise were excluded from the analysis.

FFRCT was calculated blinded to all aspects of clinical care and clinical outcomes. The results of FFRCT were not available to care providers. The techniques for calculation of FFRCT have been detailed and accuracy against invasive FFR validated previously.7,8 Briefly, 3-dimensional models of the coronary arterial tree and myocardium were segmented from the standard CTA images. Computational fluid dynamics techniques modeled coronary arterial flow under simulated maximal hyperemia. FFRCT was calculated as the ratio of mean simulated pressure to aortic pressure at all coronary artery locations measuring ≥1.8 mm in diameter. Occluded vessels were assigned a value of 0.5. The lowest per-patient FFRCT value was reported; a FFRCT ≤0.80 at any coronary location constituted a per-patient “positive” result. We also reported per-vessel lowest FFRCT value, which was used in per-vessel analysis. A FFRCT ≤0.80 at any coronary location in a given vessel constituted a per-vessel “positive” result. Transfer of data, image segmentation, FFRCT calculation and reporting typically requires less than 2 hours with the current iteration of the technology.

Invasive and non-invasive tests

Investigators in the ROMICAT II trial prospectively collected information on ICA, revascularization procedures (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery by-pass grafting) and additional non-invasive stress tests. Non-invasive stress tests included exercise treadmill electrocardiograms, nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging or stress echocardiograms. The tests were evaluated by local physicians and were reported positive if there was evidence of stress-induced ischemia.

Core laboratory assessment of coronary CTA

We performed additional core laboratory assessment of coronary CTA datasets. Three independent readers with level III experience in coronary CTA who were blinded to clinical care results evaluated coronary CTA on a per coronary segment basis using the model of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography.19 Each segment was assessed for the presence of coronary stenosis and plaque. The severity of stenosis was categorized as: 0% = no stenosis, 1–49% = non-obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD), 50–69% = moderate stenosis, ≥50% stenosis in the left main coronary artery or ≥70% in any coronary artery = severe stenosis.

Qualitative assessment for high-risk coronary plaque was performed in all coronary segments with plaque. High-risk plaque was defined as the presence of at least one of the following features: positive remodeling (remodeling index >1.1), presence of plaque with low CT attenuation of <30 HU, napkin-ring sign and spotty calcium as described previously.4

Four independent readers with level III experience in coronary CTA performed quantitative coronary CTA analysis in coronary segments with visually detectable plaques. The images were analyzed on a dedicated workstation (QAngio CT RE 2.0, Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands). Readers performed automatic detection of the coronary arteries and segmentation of luminal and outer vessel boundaries followed by manual adjustments of the vessel centerline and boundaries as needed. Reader then determined the proximal and distal reference of the coronary plaque in the adjacent normal vessel. The final results of the coronary CTA analysis were reported per coronary artery. We measured total plaque volume, volume of plaque with <30 HU and maximum remodeling index. The detailed description of the quantitative analysis was reported previously.20

Acute coronary syndrome definition

An independent clinical events committee adjudicated the presence of ACS during the index hospitalization as described previously.2 ACS was defined as acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines.21

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). Continuous data are presented as mean±standard deviation or median and 25th-75th percentile. Categorical and ordinal variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Comparisons for unpaired data were performed with the use of an independent sample t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, the Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for ordinal variables. Binominal 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the ‘exact’ method, i.e. Clopper-Pearson intervals.22 We performed multivariable multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression to evaluate the association between high-risk plaque (defined as any high-risk plaque by qualitative analysis) and FFRCT after adjustment for stenosis severity at vessel level. At patient level, we used multivariable logistic regression models, in which we studied the association of high-risk plaque, FFRCT and severe stenosis with the outcome of ACS during the index hospitalization. Based on these logistic regression models we calculated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and corresponding areas under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC), which were compared using the DeLong algorithm.23 For all analyses, a 2-tailed P value <0.05 was required to reject the null hypothesis.

Results

Study population

Of the 501 patients randomized to coronary CTA, 473 patients underwent and completed CTA scan (Figure 1). We included patients with ≥50% stenosis in at least one coronary artery (n=82, 17.3%) based on the site reads of coronary CTA. We also included patients who underwent an additional non-invasive cardiac test (n=34, 7.2%), among them 27 patients who had stenosis <50% and 7 patients who had indeterminate stenosis severity. Total of 116 patients met inclusion criteria and their coronary CTA images were submitted for FFRCT analysis. Out of 116 patients, 48 (41.4%) coronary CTA datasets were inadequate for FFRCT analysis due to motion artifacts, severe calcium blooming artifacts or excessive image noise. The characteristics of 68 subjects included in the study stratified by FFRCT results are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in baseline demographics and cardiovascular risk factors between subjects with FFRCT ≤0.80 and FFRCT >0.80 except for more men among those with abnormal FFRCT ≤0.80. Compared to those patients in whom FFRCT calculation was not feasible, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics of patients with available FFRCT measurements (Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 68 subjects included in the study stratified by FFRCT results.

| FFRCT ≤0.80 n = 40 | FFRCT >0.80 n = 28 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age - mean ± SD, years | 57.1 ± 7.2 | 53.9 ± 9.7 | 0.154 |

| Female gender - no. (%) | 6 (15.0) | 14 (50.0) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular Risk factors - no. (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 24 (60.0) | 17 (60.7) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (27.5) | 5 (17.9) | 0.400 |

| Dyslipidemia | 24 (60.0) | 18 (64.3) | 0.803 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 8 (20.0) | 11 (39.3) | 0.103 |

| Former or current smoker | 28 (70.0) | 14 (50.0) | 0.129 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 18 (45.0) | 12 (42.9) | 1.000 |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 13 (32.5) | 8 (28.6) | 0.794 |

| Beta-blockers | 9 (22.5) | 9 (32.1) | 0.413 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 14 (35.0) | 9 (32.1) | 1.000 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 5 (12.5) | 1 (3.6) | 0.389 |

| Statins | 15 (37.5) | 10 (35.7) | 1.000 |

Coronary CTA findings and FFRCT

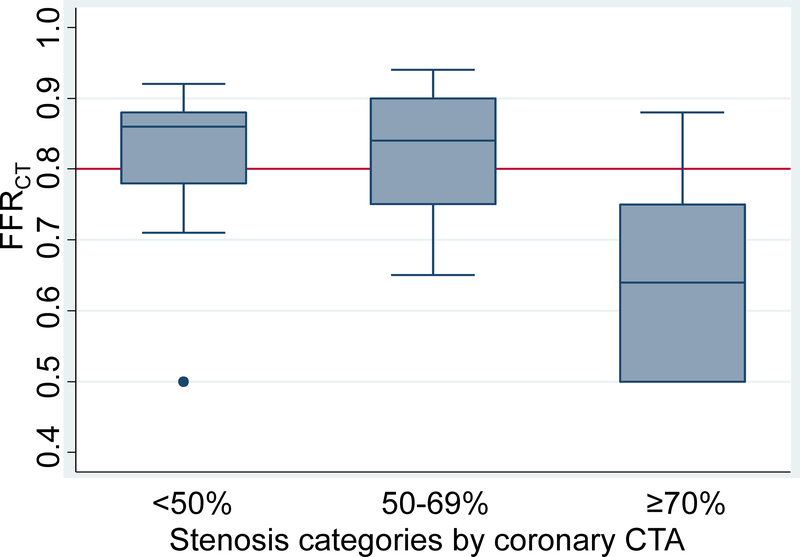

We observed association between abnormal FFRCT ≤0.80 and the presence of severe stenosis defined as stenosis ≥70% in any artery or ≥50% stenosis in the left main coronary artery as assessed by site reads of coronary CTA (Table 2). Among 33 patients with severe stenosis on coronary CTA, 28 (84.8%) had FFRCT ≤0.80 and 5 (15.2%) had FFRCT >0.80 (Figure 2). Mild stenosis (<50%) or moderate stenosis (50–69%) was more often found in patients with normal FFRCT >0.80 (Table 2). Patients with severe stenosis had lower FFRCT values (median 0.64, 25th-75th percentile 0.50–0.75) as compared to patients with moderate (median 0.84, 25th-75th percentile 0.75–0.90, p<0.001) or mild stenosis (median 0.86, 25th-75th percentile 0.78–0.88, p<0.001) (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Coronary CTA findings (site reads), acute coronary syndrome during index hospitalization and additional cardiac tests stratified by FFRCT results.

| FFRCT ≤0.80 n=40 | FFRCT >0.80 n=28 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary CTA stenosis – no. (%) | |||

| Indeterminate | 1 (2.5) | 1 (3.6) | 1.000 |

| Mild (<50%) | 5 (12.5) | 10 (35.7) | 0.036 |

| Moderate (50–69%) | 6 (15.9) | 12 (42.9) | 0.013 |

| Severe (≥70% or ≥50% left main) | 28 (70.0) | 5 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Acute coronary syndrome – no. (%) | 23 (57.5) | 4 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 20 (50.0) | 4 (14.3) | |

| Invasive coronary angiography – no. (%) | 21 (52.5) | 9 (32.1) | 0.137 |

| Coronary revascularization – no. (%) | 15 (37.5) | 3 (10.7) | 0.024 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 12 (30.0) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Coronary artery bypass | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Non-invasive stress test – no. (%) | 15 (37.5) | 17 (60.7) | 0.084 |

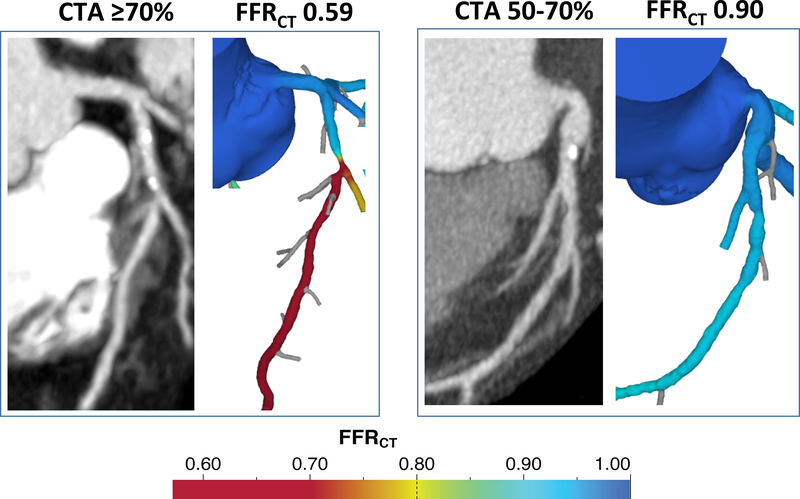

Figure 2.

Representative cases of coronary CTA and FFRCT. Left panel: 64-year-old man with acute chest pain diagnosed with unstable angina. Coronary CTA demonstrated 70–99% stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery at the origin of the first diagonal branch. FFRCT was abnormal (0.59). Invasive coronary angiography confirmed ≥70% stenosis and patient underwent stent placement. Right panel: 61-year-old woman diagnosed with non-cardiac chest pain. Coronary CTA demonstrated 50–70% stenosis in mid left anterior descending coronary artery. FFRCT was normal (0.90). Invasive coronary angiography showed 30–50% stenosis.

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plot of per patient FFRCT by categories of coronary CTA stenosis.

Association of FFRCT with ACS and coronary revascularization

ACS during the index hospitalization was diagnosed in 39.7% (27/68) patients (myocardial infarction n=3, unstable angina pectoris n=24). ACS was more often diagnosed in patients with FFRCT ≤0.80 (2¾0 patients, 57.5%) as compared to those with FFRCT >0.8 (4/28 patients, 14.3%; p<0.001, Table 2). Subjects with FFRCT ≤0.80 also underwent revascularization during the index hospitalization more often: 15/40 (37.5%) patients vs. 3/28 (10.7%) patients (p=0.024). The relative risk of ACS and revascularization in those with FFRCT ≤0.80 as compared to those with FFRCT >0.8 was 4.03 (95% CI 1.56–10.36) and 3.50 (95% CI 1.12–10.96), respectively.

Potential effects of FFRCT on downstream testing

ICA was performed in 44.1% (30/68) patients (Table 2). Among them, 73.3% (22/30) had severe stenosis on coronary CTA. Moderate stenosis was found in 20.0% (6/30) and mild stenosis in 6.7% (2/30) patients on coronary CTA. In patients with FFRCT >0.8 who underwent ICA, 37.5% (3/8) patients had severe stenosis on ICA. Among 8 patients with moderate or mild stenosis on coronary CTA, 7 patients had normal FFRCT >0.8 and only one patient with normal FFRCT was diagnosed with ACS.

Additional non-invasive stress test after coronary CTA was performed in 47.1% (32/68) patients. Among these patients, ACS was diagnosed in 18.8% (6/32). Abnormal FFRCT ≤0.80 was detected in 46.9% (15/32) patients. In the group of patients with FFRCT ≤0.80, 26.7% (4/15) patients were diagnosed with ACS. Normal FFRCT >0.80 was found in 53.1% (17/32) patients. The result of non-invasive stress test was positive for ischemia in 17.7% (3/17) patients with FFRCT >0.80. Two patients from this group were diagnosed with ACS (11.8%, 2/17, p=0.383 as compared to abnormal FFRCT). Coronary CTA showed severe stenosis in 5.9% (1/17) patients. The remaining patients had moderate (29.4%, 5/17), mild (58.8%, 10/17) or indeterminate (5.9%, 1/17) stenosis. Only one patient without severe stenosis on coronary CTA and FFRCT >0.8 was diagnosed with ACS. FFRCT could potentially decrease the need for additional non-invasive testing in half of patients (16/32 with less than severe stenosis on coronary CTA and normal FFRCT).

Core laboratory evaluation of high-risk plaque and FFRCT

We performed additional analysis with core laboratory assessment of coronary CTA. Among 16 patients with severe stenosis on coronary CTA, all 16 (100%) patients had positive FFRCT ≤0.80 (Table S2). In patients with moderate stenosis, positive FFRCT ≤0.80 was found in 9/11 (81.2%) patients. Overall, 25/27 (92.6%) patients had positive FFRCT ≤0.80 among patients with moderate or severe stenosis by core laboratory reads. In contrast, only 34/51 (66.7%) patients with moderate or severe stenosis by site reads had positive FFRCT ≤0.80. Among patients with mild stenosis by core laboratory reads, 26/41 (63.4%) had negative FFRCT >0.80, which was similar to site reads (10/15 patients, 66.7%).

In a per vessel analysis, we found good correlation between coronary stenosis and FFRCT as assessed by the core laboratory (Table 3). Vessels with abnormal FFRCT ≤0.8 had higher prevalence of high-risk plaque (any high-risk plaque and individual high-risk plaque features of positive remodeling, low CT attenuation plaque, napkin-ring sign and spotty calcium) as detected by qualitative analysis. Similar results were found in per patient analysis (data not shown). In quantitative plaque analysis, we observed higher remodeling index, total plaque volume and low CT attenuation (<30 HU) plaque volume in vessels with abnormal FFRCT ≤0.8. In multivariable multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression, the association between high-risk plaque (defined as any high-risk plaque by qualitative analysis) and FFRCT ≤0.8 was independent of stenosis severity (odds ratio 3.91, 95% CI 1.55–9.85, p=0.004). In the multivariable model at patient level, the addition of high-risk plaque (odds ratio 16.47, 95%CI 1.13–240.81, p=0.041) and FFRCT (odds ratio 1.67, 95%CI 0.40–7.09, p=0.483) to stenosis (odds ratio 40.18, 95%CI 3.44–469.36, p=0.003) improved discriminatory capacity for ACS as compared to stenosis only (AUC: 0.87, 95%CI 0.79–0.95 vs. 0.77, 95%CI 0.67–0.86; p=0.003; Figure S1).

Table 3.

Results of core laboratory assessment for stenosis, qualitative high-risk plaque and quantitative plaque stratified by FFRCT results (per vessel analysis).

| FFRCT ≤0.80 n=71 | FFRCT >0.80 n=175 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stenosis – no. (%) | |||

| Mild (<50%) | 37 (52.1) | 170 (97.1) | <0.001 |

| Moderate (50–69%) | 13 (18.3) | 4 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Severe (≥70% or ≥50% LM) | 21 (29.6) | 1 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Qualitative plaque – no. (%) | |||

| Any high-risk plaque | 48 (67.6) | 52 (29.7) | <0.001 |

| Positive remodeling | 23 (32.4) | 9 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| Low HU plaque | 15 (23.1) | 5 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Napkin-ring sign | 13 (18.3) | 2 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Spotty calcium | 41 (57.8) | 50 (28.6) | <0.001 |

| Quantitative plaque – mean ± SD | |||

| Total plaque volume, mm3 | 198.5 ± 188.8 | 43.2 ± 79.7 | <0.001 |

| Plaque Volume <30 HU, mm3 | 4.7 ± 7.6 | 1.1 ± 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Remodeling index | 1.24 ± 0.29 | 1.05 ± 0.14 | <0.001 |

Discussion

We performed analysis of non-invasive FFRCT in patients from the ROMICAT II trial who underwent coronary CTA and had moderate or severe coronary stenosis or required additional non-invasive stress test. We demonstrated the feasibility of FFRCT analysis in acute chest pain population in multicenter, multivendor setting. Our study showed that severity of stenosis on coronary CTA correlated with FFRCT measurements. Patients with abnormal FFRCT were also more likely diagnosed with ACS and more often required revascularization. In coronary plaque analysis, we observed association of the presence of high-risk plaque features with abnormal FFRCT values, which persisted after adjustment for stenosis severity.

Feasibility of FFRCT in acute chest pain population

Prior studies reported good correlation of FFRCT with invasive FFR as well as relationship to outcomes in populations of outpatients with stable chest pain.7,8,12–14,24 Large multicenter trials reported that 71–89% of coronary CTA datasets were of sufficient images quality for FFRCT analysis.7,8,13 The results from clinical practice with focused image optimization required for FFRCT showed event better results with 97–99% of coronary CTA having image quality sufficient for FFRCT analysis.25,26 In our study, we demonstrated that the evaluation of FFRCT in patients with acute chest pain in the ED was feasible. We selected a population with high prevalence of CAD and patients who required additional testing. Despite the challenging population characteristics, we observed that FFRCT was feasible in 59% of patients. This was possible despite the fact that coronary CTA scans were not acquired with the goal to perform FFRCT and were acquired before 2011, i.e. with older CT equipment. The FFRCT acceptance was similar to the analysis from the PROspective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE), in which 67% of coronary CTA datasets were evaluable.14 In the future prospective studies of FFRCT in acute chest pain populations, the investigators will have to pay attention to obtain high image quality necessary for the analysis. Rapid evaluation in the core laboratory with turnaround time of a few hours will be necessary for the implementation of FFRCT into the ED workflow. In addition to FFRCT performed as an offsite analysis, which may require longer processing times, on-site FFRCT solutions tested in smaller, single center studies have been demonstrated to provide results that compare favorably with invasive FFR and have been feasible in patients with suspected ACS.17,24,25 Considering on-site assessment may be more time efficient, especially in the setting of acute chest pain where efficient time management is crucial, but future studies will be needed to evaluate this concept.

Correlation of FFRCT with stenosis and ACS outcomes

Prior studies showed correlation of FFRCT with stenosis severity14, which was confirmed in our study. However, there was still substantial disagreement. Mild or moderate stenosis was found on coronary CTA in 28% (1¼0) patients with abnormal FFRCT ≤0.8. There were 18% (5/28) patients with severe stenosis as assessed by site coronary CTA reads who had normal FFRCT >0.8. Therefore, overall there was disagreement in 24% (16/68) patients. These findings are similar to the results from the PROMISE trial, in which there was 31% of patients with disagreement between coronary CTA and FFRCT and 29% of patients with disagreement between ICA and FFRCT.14 The disagreement was higher in the Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography: Next Steps (NXT) trial, in which the investigators observed disagreement between coronary CTA and FFRCT in 47% of patients.8 Our results are also in line with experience comparing invasive evaluation of ICA with FFR, which showed discrepancy rate of 25% in the Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography in Multivessel Evaluation (FAME) trial.10

An interesting observation from our study is the difference in the agreement between coronary CTA and FFRCT when core laboratory evaluation was used. We found that all patients graded as having severe stenosis on coronary CTA by core laboratory readers were also found to have FFRCT ≤0.8. Overall, we found lower grading of stenosis severity in core laboratory reads. The results are in concordance with the recent analysis from the PROMISE trial that showed lower prevalence of significant stenosis in core laboratory CTA reads as compared to the site reads.26 Less conservative assessment of stenosis severity (i.e. less patients with significant stenosis) did not affect the predictive accuracy of CTA for the future majors adverse cardiovascular events.26 These results suggest that combined “less conservative” evaluation of coronary CTA for stenosis with detection of hemodynamically significant lesions using FFRCT is a concept that will need to be prospectively evaluated.

We evaluated the association of FFRCT, which was not used for the clinical decision-making in the ROMICAT II trial, with the outcome of ACS during the index hospitalization. There was a strong association between abnormal FFRCT and the diagnosis of ACS. Among 27 patients with the diagnosis of ACS, 23 (85%) patients had FFRCT ≤0.8. This observation showed that hemodynamic significance of coronary lesions is important predictor of ACS in acute chest pain setting. Our results mirror the prior experience from stable chest pain population. In the PROMISE trial, the association of FFRCT with revascularization and major adverse cardiovascular events was significantly stronger than for severe stenosis on CTA (hazard ratio 4.31 vs. 2.90, p=0.033), a notable result as stenosis guided the clinical decision for coronary revascularization, whereas FFRCT was not available to caregivers in the trial.14

Four out of 28 patients with FFRCT >0.8 were diagnosed with ACS. These discrepant results, reflect clinical practice, in which further testing may be driven by clinical presentation in acute chest pain. Furthermore, prior studies showed remaining discordance of FFRCT results with invasive FFR, especially around the threshold of 0.8, and between FFRCT and functional stress testing.27,28

FFRCT and coronary plaque characteristics

The presence of high-risk plaque features, such as positive remodeling, low CT attenuation, napkin-ring sign and spotty calcium, on coronary CTA is associated with the presence of ACS in acute setting and increased risk of future cardiovascular events in stable chest pain patients.4,29 In a secondary analysis of Determination of Fractional Flow Reserve by Anatomic Computed Tomographic Angiography (DeFACTO) trial of stable chest pain patients, qualitative and quantitative measures of coronary plaque were independently associated with lesions causing ischemia as confirmed by invasive FFR.16 Similar observations were made by the investigators in the NXT trial who found association of significant stenosis, non-calcified and low CT attenuation plaque volume with abnormal FFRCT ≤0.8.15 The volume of low CT attenuation plaque and FFRCT was incremental to stenosis in prediction of lesion specific ischemia as assessed by invasive FFR. The incremental value of plaque assessment and FFRCT was also present in patients with non-significant stenosis on coronary CTA. We extended this novel observation of the association between high-risk plaque features and total and low CT attenuation plaque volume with hemodynamic significance as assessed by FFRCT, which was independent of the presence of significant stenosis, in the acute chest pain population. Our results provide an additional piece of evidence supporting the notion that coronary plaque characteristics are an important determinant of hemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis.

Limitations

We performed FFRCT analysis in a subgroup of patients in the ROMICAT II trial. This approach may introduce selection bias. The results of coronary CTA based on site reads affected the clinical decisions and were also used to select the patients included in our substudy. Only 3 out of 22 patients diagnosed with ACS had myocardial infarction. Remaining 19 patients were diagnosed with unstable angina. This limits our ability to study relationship between stenosis detected by site reads and FFRCT with respect to the prediction of ACS. The estimates of decreased need for secondary testing and ICA are affected by those limitations as well. Further prospective studied will be necessary to evaluate whether implementation of FFRCT in the evaluation of patients with acute chest pain in the ED can decrease the rates of secondary testing. Invasive FFR was not performed routinely in the ROMICAT II trial. Therefore, we were unable to confirm the results of FFRCT with invasive FFR in patients who underwent ICA. A fairly high proportion of coronary CTAs were not suitable for FFRCT analysis, which is reflective of older generations of CT scanners and image acquisition not being optimized for FFRCT.

Conclusions

We showed that FFRCT measurements correlated with the anatomic severity of stenosis on coronary CTA. Abnormal FFRCT was associated with the presence of ACS and coronary revascularization. We found association between the presence of high-risk plaque and FFRCT, which was independent of stenosis severity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Campbell Rogers and Souma Sengupta (Heart Flow) for calculation of FFRCT.

Disclosures

ROMICAT II Support NIH U01HL092040 and U01HL092022, ACRIN

Ferencik: Research Grant/Significant: American Heart Association Fellow to Faculty Award 13FTF16450001

Lu: Research Grant/Significant: American Roentgen Ray Society Scholarship.

Truong: Research Grant/Significant: NIH/NHLBI K23HL098370 and L30HL093896, St. Jude Medical, American College of Radiology Imaging Network, and Duke Clinical Research

Nagurney: Research Grant/Significant: Alere/Biosite, Brahms Ltd/Thermo-Fisher, Nanosphere; Consultant/Advisory/Significant: Board CardioDx

Hoffmann: Research Grant/Significant: NIH U01HL092040, U01HL092022, Siemens Medical Solutions, Heart Flow Inc; Consultant/Advisory Board/Significant: Heart Flow All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Two tables and one figure.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldstein JA, Chinnaiyan KM, Abidov A, et al. The CT-STAT (Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(14):1414–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):299–308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B, et al. CT angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1393–1403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puchner SB, Liu T, Mayrhofer T, et al. High-risk plaque detected on coronary CT angiography predicts acute coronary syndromes independent of significant stenosis in acute chest pain: results from the ROMICAT-II trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(7):684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seneviratne SK, Truong QA, Bamberg F, et al. Incremental diagnostic value of regional left ventricular function over coronary assessment by cardiac computed tomography for the detection of acute coronary syndrome in patients with acute chest pain: from the ROMICAT trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(4):375–383. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.892638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feuchtner GM, Plank F, Pena C, et al. Evaluation of myocardial CT perfusion in patients presenting with acute chest pain to the emergency department: comparison with SPECT-myocardial perfusion imaging. Heart. 2012;98(20):1510–1517. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1237–1245. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nørgaard BL, Leipsic J, Gaur S, et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography: Next Steps). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budoff MJ, Nakazato R, Mancini GBJ, et al. CT Angiography for the Prediction of Hemodynamic Significance in Intermediate and Severe Lesions: Head-to-Head Comparison With Quantitative Coronary Angiography Using Fractional Flow Reserve as the Reference Standard. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(5):559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonino PAL, Fearon WF, de Bruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(25):2816–2821. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):991–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas PS, de Bruyne B, Pontone G, et al. 1-Year Outcomes of FFRCT-Guided Care in Patients With Suspected Coronary Disease: The PLATFORM Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(5):435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas PS, Pontone G, Hlatky MA, et al. Clinical outcomes of fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography-guided diagnostic strategies vs. usual care in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: the prospective longitudinal trial of FFR(CT): outcome and resource impacts study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(47):3359–3367. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu MT, Ferencik M, Roberts RS, et al. Noninvasive FFR Derived From Coronary CT Angiography: Management and Outcomes in the PROMISE Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(11):1350–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaur S, Øvrehus KA, Dey D, et al. Coronary plaque quantification and fractional flow reserve by coronary computed tomography angiography identify ischaemia-causing lesions. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(15):1220–1227. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park H-B, Heo R, ó Hartaigh B, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque characteristics by CT angiography identify coronary lesions that cause ischemia: a direct comparison to fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tesche C, De Cecco CN, Caruso D, et al. Coronary CT angiography derived morphological and functional quantitative plaque markers correlated with invasive fractional flow reserve for detecting hemodynamically significant stenosis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(3):199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driessen RS, Stuijfzand WJ, Raijmakers PG, et al. Effect of Plaque Burden and Morphology on Myocardial Blood Flow and Fractional Flow Reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(5):499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, et al. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8(5):342–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferencik M, Mayrhofer T, Puchner SB, et al. Computed tomography-based high-risk coronary plaque score to predict acute coronary syndrome among patients with acute chest pain--Results from the ROMICAT II trial. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9(6):538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(18):e426–e579. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318212bb8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The Use of Confidence or Fiducial Limits Illustrated in the Case of the Binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26(4):404–413. doi: 10.2307/2331986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delong ER, Delong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko BS, Cameron JD, Munnur RK, et al. Noninvasive CT-Derived FFR Based on Structural and Fluid Analysis: A Comparison With Invasive FFR for Detection of Functionally Significant Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(6):663–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duguay TM, Tesche C, Vliegenthart R, et al. Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve Based on Machine Learning for Risk Stratification of Non-Culprit Coronary Narrowings in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(8):1260–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu MT, Meyersohn NM, Mayrhofer T, et al. Central Core Laboratory versus Site Interpretation of Coronary CT Angiography: Agreement and Association with Cardiovascular Events in the PROMISE Trial. Radiology. 2018;287(1):87–95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017172181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook CM, Petraco R, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Computed Tomography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve : A Systematic Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(7):803–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Driessen RS, Danad I, Stuijfzand WJ, et al. Comparison of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography, Fractional Flow Reserve, and Perfusion Imaging for Ischemia Diagnosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(2):161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motoyama S, Ito H, Sarai M, et al. Plaque Characterization by Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography and the Likelihood of Acute Coronary Events in Mid-Term Follow-Up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.