Abstract

Our study objectives were to examine the impact of anemia and heart failure (HF) on in-hospital complications and post-discharge outcomes (7 and 30-day rehospitalizations and mortality) in adults ≥65 years hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). We used multivariable adjusted logistic regression models to examine the association between the presence of anemia and/or HF and the examined outcomes. The study population consisted of 3,863 patients ≥65 years hospitalized with AMI at the 3 major medical centers in Worcester, MA, during 6 annual periods between 2001 and 2011. Individuals were categorized into 4 groups based on the presence of previously diagnosed anemia (hemoglobin ≤10mg/dl) and/or HF: those without these conditions (n=2,300), those with anemia only (n=382), those with HF only (n=837), and those with both conditions (n=344). The median age of the study population was 79 years and 49% were men. Individuals who had been previously diagnosed with anemia and HF had the highest proportion of older adults (≥85 years) and the lowest proportion of those who had received any cardiac interventional procedure during hospitalization. After multivariable adjustment, individuals who presented with both previously diagnosed conditions were at greatest risk for experiencing adverse events. Patients who presented with HF only were at higher risk for developing several clinical complications during hospitalization, whereas those with anemia only were at slightly higher risk of being rehospitalized within 7-days of their index hospitalization. In conclusion, anemia and HF are prevalent chronic conditions that increased the risk of adverse events in older adults hospitalized with AMI.

Keywords: anemia, multimorbidity, myocardial infarction

Anemia and heart failure (HF) are recognized as important independent risk factors for morbidity and mortality in older adults hospitalized with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI).1-4 Anemia is a prevalent condition in older adults with an AMI, with a frequency ranging from 6% to 45%, and this condition has been associated with a greater risk of dying at the time of hospitalization for AMI as compared to those without anemia.1-4 The magnitude of HF increases with advancing age,5 and patients with previously diagnosed HF are at greater risk for subsequent morbidity and mortality when hospitalized for an AMI in comparison with those who do not have this clinical syndrome.6,7 Although a number of studies have examined the natural history of patients who present with either anemia or HF at the time of hospitalization for AMI,1-7 there are extremely limited data available describing the characteristics, management, and frequency of adverse outcomes in adults ≥ 65 years who present with either or both of these 2 prevalent conditions at the time of hospitalization for AMI. The objectives of this observational study were to describe overall differences in the characteristics, in-hospital management, clinical complications, in-hospital death rates, and 30-day outcomes in patients with preexisting anemia and/or HF, as compared with those without these conditions, who were diagnosed with AMI at the 3 major medical centers in central Massachusetts on a biennial basis between 2001 and 2011.8-10

Methods

The Worcester Heart Attack Study is an ongoing population-based investigation that is examining long-term trends in the clinical epidemiology of AMI among residents of the Worcester, Massachusetts (MA), metropolitan area hospitalized at all medical centers in central MA on an approximate biennial basis.8-12

Computerized printouts of residents of central MA admitted to the 3 largest hospitals in Worcester, MA with possible AMI [International Classification of Disease (ICD) 9 codes 410-414, and 786.5) on a biennial basis between 2001 and 2011 were identified. Cases of possible AMI were independently validated using predefined criteria for AMI, including diagnoses of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).13,14 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Trained nurses and physicians abstracted information on patient’s demographic and clinical characteristics, hospital treatment practices, and short-term outcomes through the review of hospital medical records. These characteristics included patient's age, sex, race/ethnicity, hospital length of stay, and previously diagnosed chronic conditions. The presence of anemia was defined based on the review of hospital medical records as well as hospital lab values (hemoglobin levels ≤10 mg/dl)15 at the time of the index admission for AMI. The presence of HF was defined based on the review of information contained in hospital medical records as was information on the development of important in-hospital complications including atrial fibrillation,16 cardiogenic shock,17 heart failure,18 stroke,19 and death. Data on the receipt of 3 coronary diagnostic and interventional procedures [cardiac catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)] during hospitalization, and evidence-based pharmacotherapies during hospitalization, namely angiotensin converting inhibitors (ACE-I)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), aspirin, beta blockers, and lipid lowering agents were also collected.

A rehospitalization was defined as the patient's first admission to a study hospital for any reason within 7 or 30 days of discharge after their index hospitalization for AMI during the years under study.

We stratified our study population into 4 groups according to the presence of previously diagnosed anemia and/or HF: those without anemia or HF, those with anemia only, those with HF only, and patients who presented with both conditions. We compared differences in the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, hospital management practices, and development of in-hospital complications and postdischarge hospital readmissions and mortality between each of these 4 groups using chi-square tests for categorical variables and the ANOVA test for continuous variables.

For purposes of more systematically examining the association between the presence of previously diagnosed anemia and/or HF with the risk of dying during the patient’s index hospitalization, developing clinically significant in-hospital complications, or having a rehospitalization or dying within 7 or 30 days after being discharged form the hospital, we used logistic regression modeling, adjusting for several potentially confounding demographic and clinical factors of prognostic importance in these models. The variables we controlled for included age, sex, type of AMI (STEMI vs NSTEMI), presence of other chronic conditions, hospital length of stay, and the hospital receipt of 5 evidence-based cardiac medications and 3 coronary diagnostic and interventional procedures.

Results

A total of 3,863 residents of central MA 65 years and older were hospitalized with AMI at the 3 largest teaching and community medical centers in Worcester, MA, between 2001 and 2011. The median age of this patient population was 79 years and 48.9% were men.

Patients without anemia or HF were the youngest and were more likely to be male as compared with those in the other 3 groups (Table 1). Individuals who presented with HF, with or without anemia, had the highest proportion of individuals diagnosed with an acute NSTEMI (Table 1). Relatively similar trends were observed with regards to the frequency distribution of other previously diagnosed chronic conditions in the 4 comparison groups. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and a previous AMI were the most common chronic conditions diagnosed in our study population.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics according to the presence of previously diagnosed anemia and/or heart failure

| Anemia/Heart failure | 0/0 | +/0 | 0/+ | +/+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n=2,300) | (n=382) | (n=837) | (n=344) |

| Age (years) (median) | 77.0 | 81.0% | 81.0% | 81.0% |

| 65-74 | 35.7% | 23.6% | 24.0% | 21.5%* |

| 75-84 | 40.1% | 39.0% | 39.6% | 40.1%** |

| ≥85 | 24.2% | 37.4% | 36.4% | 38.4%* |

| Men | 51.2% | 41.1% | 47.1% | 46.5%* |

| White | 91.5% | 93.3% | 92.2% | 91.1% |

| NSTEMI | 68.5% | 78.5% | 83.0% | 86.6%** |

| Length of stay (days, median) | 4.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% | 5.0%* |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 30.3% | 36.9% | 58.3% | 60.8%** |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13.4% | 16.2% | 32.5% | 34.6%** |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13.3% | 40.8% | 34.7% | 58.7%** |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary | 17.0% | 20.7% | 27.2% | 30.8%** |

| disease | ||||

| Depression | 13.4% | 23.6% | 18.6% | 22.4%** |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.2% | 41.6% | 49.7% | 54.7%** |

| Hyperlipidemia + | 56.5% | 57.9% | 59.1% | 62.5% |

| Hypertension ++ | 77.1% | 84.8% | 85.1% | 86.6%** |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 16.4% | 26.2% | 29.2% | 37.5%** |

| Stroke | 12.3% | 15.7% | 17.3% | 22.1%** |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.5% | 10.7% | 13.0% | 10.6% |

| Glucose (mg/dL) median | 145% | 151% | 169% | 162% |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min per 1.73 m2) median | 57.2% | 45.5% | 43.0% | 34.1% |

| Complications during hospitalization | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 24.6% | 25.1% | 31.5% | 28.5%** |

| Cardiogenic shock | 6.4% | 3.1% | 6.3% | 5.5% |

| Heart failure | 43.0% | 54.7% | 75.2% | 77.3%** |

| Stroke | 2.6% | 1.3% | 2.0*% | 1.2% |

| Death | 10.7% | 10.7% | 13.9% | 18.0%** |

NSTEMI: Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. (Significant *P<.01; **P<.001)

Hyperlipidemia + defined as total serum cholesterol level > 200 mg/dL.

Hypertension++ defined as systolic ≥140/>diastolic 90 mm Hg.

The 2 more common complications during the hospital stay in our 4 comparison groups were AF and HF. Approximately 1 in every 3 patients with HF with or without anemia developed AF and 3 in every 4 patients with HF with or without anemia developed HF (Table 1). Individiduals who presented with both anemia and HF were at the greatest risk for dying during their hospitalization for AMI.

Patients who presented with HF with or without anemia had the lowest proportion of individuals who were treated in the hospital with beta-blockers and lipid lowering medications (Table 2). The proportion of patients with HF with or without anemia that received any cardiac diagnostic/ interventional procedure was significantly lower as compared with the other 2 groups (Table 2).

Table 2:

Clinical management during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction according to the presence of previously diagnosed anemia and/or heart failure

| Anemia/Heart failure | 0/0 | +/0 | 0/+ | +/+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic/Interventional Procedures | (n=2,300) | (n=382) | (n=837) | (n=344) |

| Cardiac catheterization | 60.0% | 38.5% | 37.5% | 26.5%** |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 7.5% | 4.7% | 4.4% | 1.2%** |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 40.2% | 23.3% | 21.4% | 16.0%** |

| Medications | ||||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/Angiotensin receptor blockers | 67.0% | 59.7% | 69.1% | 64.8%* |

| Aspirin | 93.4% | 86.9% | 89.4% | 88.1%** |

| Beta blockers | 90.0% | 90.8% | 87.0% | 87.5%* |

| Lipid lowering medications | 74.7% | 73.8% | 65.7% | 66.9%** |

| Cumulative number of cardiac medications | ||||

| Any 2 medications | 18.4% | 22.3% | 22.1% | 25.9%* |

| Any 3 medications | 30.6% | 30.1% | 32.9% | 29.4% |

| All 4 medications | 51.0% | 47.6% | 45.0% | 44.8%* |

P<.01;

P<.001

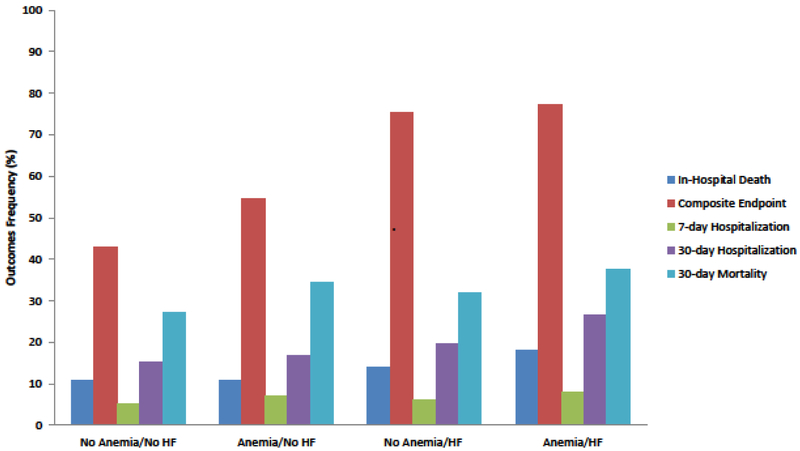

Figure 1 summarizes the frequency of adverse outcomes according to the presence of anemia and/or HF. Similar trends were found in the frequency of in-hospital death or in-hospital complications and 30-day rehospitalization in patients with HF with and without anemia (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Frequency of adverse outcomes according to the presence of anemia and/or heart failure.

After controlling for several factors of prognostic importance, we found an increased risk of dying during hospitalization in patients who presented with HF and anemia as compared to those without these conditions (Table 3). The risk of developing any clinically signficant in-hospital complication, namely HF, stroke, cardiogenic shock, or AF was increased across all comparison groups, with the highest risk observed for patients with HF, with or without anemia, as compared to those without these chronic conditions.

Table 3:

Adverse outcomes according to the presence of previously diagnosed anemia and/or heart failure

| Anemia/Heart failure | 0/0 | +/0 | 0/+ | +/+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | (n=2,300) | (n=382) | (n=837) | (n=344) |

| In-Hospital death, OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Unadjusted model, | 1.01(0.71;1.42) | 1.34(1.06;1.70) | 1.84(1.35;2.49) | |

| Adjusted model | 0.98(0.67;1.45) | 1.16(0.88;1.54) | 1.66(1.16;2.36) | |

| Composite endpoint: Atrial fibrillation, heart failure, cardiogenic shock or stroke OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Unadjusted model | 1.37(1.09;1.71) | 3.86(3.16;4.71) | 4.16(3.08;5.63) | |

| Adjusted model | 1.19(0.93;1.53) | 3.13(2.50;3.90) | 3.15(2.26;4.38) | |

| 7-day Hospitalization OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Unadjusted model | 1.36(0.88;2.09) | 1.18(0.85;1.65) | 1.58(1.03;2.43) | |

| Adjusted model | 1.61(1.02;2.56) | 1.26(0.86;1.83) | 1.77(1.08;2.89) | |

| 30-day Hospitalization OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Unadjusted model | 1.11(0.83;1.49) | 1.37(1.12;1.68) | 2.02(1.55;2.63) | |

| Adjusted model | 1.06(0.77;1.46) | 1.25(0.99;1.58) | 1.89(1.39;2.57) | |

| 30-day mortality OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Unadjusted model | 1.40(1.11;1.76) | 1.25(1.05;1.49) | 1.60(1.27;2.03) | |

| Adjusted model | 1.22(0.94;1.59) | 1.11 (0.91;1.36) | 1.45(1.11;1.91) | |

Models full adjusted for: age, sex, type of AMI, presence of comorbidities based on medical history, use of in-hospital medications, and receipt of cardiac and diagnostic interventional procedures.

The risk of being readmitted to the hospital within 7 days after the index hospitalization for AMI was significantly higher among patients with previously diagnosed anemia only, and among those with both anemia and HF, as compared with those without these conditions. Slightly different trends were found in the risk of readmission within 30 days, with the highest risk noted among patients with HF and anemia (Table 3). Similar results were observed with regards to the risk of dying at 30 days with the highest estimates noted in those who presented with both chronic conditions.

Discussion

In this investigation of more than 3,800 patients ≥65 years hospitalized with a confirmed AMI at the 3 largest tertiary care and community medical centers in central MA, patients presented with a considerable burden of previously diagnosed anemia and HF. After multivariable adjustment, patients who presented with both chronic conditions had the greatest risk for developing each of the adverse outcomes examined.

Our findings are consistent with the results from other investigations that have examined the frequency of various chronic conditions in patients hospitalized with AMI who presented with HF and/or anemia.6,20,21 The Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications trial included over 2,000 patients hospitalized with AMI. Researchers reported that those who presented with anemia at the time of hospitalization (13% of the study sample) had a high prevalence of preexisting diabetes mellitus, hypertension,and peripheral arterial disease.20 Among patients enrolled in The Second National Registry of AMI (n=~36,000), individuals with previously diagnosed HF had a higher prevalence of previous AMI, diabetes, and hypertension as compared to those without HF.6 These findings suggest that patients with HF and/or anemia carry a significant burden of other chronic conditions which may complicate their management and adversely impact their outcomes during hospitalization for AMI.

We observed relatively small differences across the 4 comparison groups in the precribing of in-hospital cardiac medications. Older adults who presented with anemia, however, were less likely to have been prescribed ACEI/ARBs and aspirin whereas older patients who presented with HF, with or without anemia, were less likely to have received beta-blockers and lipid lowering medications during their hospitalization. Most clinical trials have typically excluded older adults with HF and anemia, which has led to evidence gaps in how to best treat this medically complex population.13-14 Another finding of our investigation is that patients with HF and anemia were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization procedures. Thus, there is a clear need for developing evidence-based data to help clinicians caring for these patients given their presence of chronic conditions and high risk for adverse clinical outcomes.

The individual or combined effects of anemia and HF on the occurrence of adverse outcomes in older adults hospitalized with AMI have been infrequently studied.7,22 In a multicenter registry of patients hospitalized with STEMI, patients who presented with previously diagnosed HF were 3 times more likely to have died during hospitalization as compared to those without HF.22 Similar findings were observed in more than 45,000 individuals hospitalized with NSTEMI and previous HF; these individuals had twice the risk of dying during hospitalization as compared to those without HF.7

Our findings suggest that individuals who presented with anemia were at higher risk for developing in-hospital complications, being readmitted to the hospital within 7 days, or dying within 30-days after hospitalization. In a study of more than 5,000 patients admitted to the Erasmus University Medical Center for AMI, patients with anemia had a 40% increased risk of dying within 30-days after the index hospitalization as compared to those without anemia.4

The combined effects of anemia and HF on adverse outcomes in older individuals hospitalized with AMI are less well known. We found an increased risk for each of our examined outcomes in patients who presented with HF and anemia as compared to those without these chronic conditions. We were unable to find other studies that examined the combined effects of HF and anemia on adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with AMI. In the Rochester (MN) epidemiology project, patients with an incident AMI who had been previously diagnosed with anemia or HF were at increased risk of re-hospitalization; no information was, however, presented about the impact of the combined effects of both conditions.23 More comprehensive studies need to examine the combined impact of anemia and HF on adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with AMI.

The strengths of the present study include its large sample of older men and women hospitalized with AMI. Several limitations need to be acknowledged, however, in the interpretation of the present findings. Since our study population included only patients who had been hospitalized in the Worcester metropolitan area, one needs to be careful to extrapolate our findings to those who reside in other geographic areas. Since the majority of study patients were white, the generalizability of our findings to other race/ethnic groups may be limited. Lastly, detailed information about the duration or severity of the chronic conditions we examined was not available.

Our findings suggest that patients ≥65 years who presented with anemia and HF at hospital admission for AMI are at greatest risk for developing adverse outcomes as compared to those without these conditions. Patients who presented with HF with or without anemia were less likely to have been prescribed evidence-based medications and/or undergone coronary revascularization. Given the extremely limited published evidence that exists to guide the treatment of this vulnerable population, there is a clear need for developing guidelines to help healthcare providers caring for these patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grants numbers: RO1 HL35434 and 1 R01 HL135219-02). Drs J.G, R.J.G, and J.Y.’s effort was supported in part by funding from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Grant number: U01HL105268). Drs. M.T and J.H.G were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (Grant numbers: R24AG045050 and R33AG057806).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, Burton PB, Murphy SA, McCabe CH. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2005; 111:2042–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WC, Fang HY, Chen HC1, Chen CJ, Yang CH, Hang CL, Wu CJ, Fang CY. Anemia: A significant cardiovascular mortality risk after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated by the comorbidities of hypertension and kidney disease. PLoS One 2017;12(7):e0180165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariza-Solé A, Formiga F, Salazar-Mendiguchía J, Garay A, Lorente V, Sánchez-Salado JC, Sánchez-Elvira G, Gómez-Lara J, Gómez-Hospital JA, Cequier A. Impact of anaemia on mortality and its causes in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Younge JO, Nauta ST, Akkerhuis KM, Deckers JW, van Domburg RT. Effect of anemia on short- and long-term outcome in patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res 2013; 113(6):646–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu AH, Parsons L, Every NR, Bates ER: Second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction Hospital outcomes in patients presenting with congestive heart failure complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the Second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI-2). J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40(8): 1389–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roe MT, Chen AY, Riba AL, Goswami RG, Peacock WF, Pollack CV Jr, Collins SP, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED: CRUSADE Investigators. Impact of congestive heart failure in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2006. ;97:1707–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Recent changes in attack and survival rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975 through 1981): The Worcester Heart Attack Study. JAMA 1986; 255:2774–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Incidence and case fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975–1984): The Worcester Heart Attack Study. Am Heart J 1988; 115:761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. A two-decade (1975 to 1995) long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 33:1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Dalen JE, Alpert JS, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. A 30-year perspective (1975-2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009; 2:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med 2011; 124:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Philippides GJ, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Zidar JP, Anderson JL. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:645–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: e78–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stucchi M, Cantoni S, Piccinelli E, Savonitto S, Morici N. Anemia and acute coronary syndrome: current perspectives. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2018; 14:109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Wu J, Gore JM. Recent trends in the incidence rates of and death rates from atrial fibrillation complicating initial acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Am Heart J 2002; 143:519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg RJ, Spencer F, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation 2009; 119:1211–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McManus DD, Chinali M, Saczynski JS, Gore JM, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. 30-Year Trends in Heart Failure in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107:353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saczynski JS, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Gurwitz JH, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Twenty-year trends in the incidence of stroke complicating acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:2104–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikolsky E, Aymong ED, Halkin A, , Grines CL, Cox DA, Garcia E, Mehran R, Tcheng JE, Griffin JJ, Guagliumi G, Stuckey T, Turco M, Cohen DA, Negoita M, Lansky AJ, Stone GW. Impact of anemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis from the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anker SD, Voors A, Okonko D, Clark AL, James MK, von Haehling S, Kjekshus J, Ponikowski P, Dickstein K; OPTIMAAL Investigators. Prevalence, incidence, and prognostic value of anemia in patients after an acute myocardial infarction: data from the OPTIMAAL trial. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1331–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auffret V, Leurent G, Gilard M, Hacot JP, Filippi E, Delaunay R, Rialan A, Rouault G, Druelles P, Castellant P, Coudert I, Boulanger B, Treuil J, Bot E, Bedossa M, Boulmier D, Le Guellec M, Donal E, Le Breton H. Incidence, timing, predictors and impact of acute heart failure complicating ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol 2016; 221:433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Killian JM, Bell MR, Jaffe AS, Roger VL. Thirty-Day Rehospitalizations After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]