Abstract

Vitamin D3 modulates immune response, induces endogenous antimicrobial peptide production, and enhances innate immunity to defend against infections. These findings suggest that incorporating vitamin D3 into medical devices or scaffolds could positively modulate host immune response and prevent infections. In the current study, we evaluated host responses and endogenous antimicrobial peptide production using 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3)-eluting radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds in human immune system-engrafted mice. We transformed traditional 2D electrospun nanofiber membranes into radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds using the concept of solid of revolution and an innovative gas-foaming technique. Such scaffolds can promote rapid cellular infiltration and neovascularization. The infiltrating immune cells within subcutaneously implanted 25(OH)D3-containing scaffolds mainly consisted of human macrophages in the M1 phase (CCR7+), mice macrophages in the M2 phase (CD206+), and human cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) other than few human T-helper cells (CD4+). The 25(OH)D3-eluting nanofiber scaffolds significantly inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6), while accelerating the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) within the scaffolds. Additionally, we observed increased expression of human cathelicidin LL-37 within the 25(OH)D3-eluting scaffolds, while no LL-37 expression was observed in the control. Together, these findings support further work in the design of vitamin D3-eluting medical devices or scaffolds for modulating immune response and promoting antimicrobial peptide production. This could potentially reduce the inflammatory response, prevent infections, and eventually improve success rates of implants.

Keywords: 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, sustained release, radially aligned nanofiber scaffolds, cathelicidin production, inflammatory response

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Inflammation and infections often cause failure of medical devices, grafts, scaffolds, and tissue-engineered constructs after implantation [1]. Positive modulation of the host response (e.g., a reduced inflammatory response) to implants, scaffolds, and tissue-engineered constructs may reduce the failure rate [2]. Inducing endogenous antimicrobial peptide production through the innate immune system could prevent infection while eliminating the development of multidrug resistance from the use of traditional antibiotics [3]. Vitamin D3 plays an important role in modulating the immune response, reducing inflammation, and inducing endogenous antimicrobial peptide expression [4]. Previous studies showed that free drug vitamin D3 inhibits monocyte/macrophage proinflammatory cytokine production by targeting MAPK phosphatase-1 and NF-κB [5]. Pathogens activate the monocyte Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and induce the expression of the vitamin-D-activating mitochondrial enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) [6]. 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3), the circulating form of vitamin D3, enters monocytes in its free form and is converted into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), the active form of vitamin D3, by CYP27B1, which can then bind to vitamin D receptor (VDR) [6]. This binding induces the expression of VDR target genes including the cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene [6–9]. The peptide LL-37 disrupts bacterial membranes and promotes autophagy to enhance antibacterial activities of the macrophage [10]. Regulation of the CAMP gene by vitamin D occurs only in humans and primates; therefore, research is focused on investigating vitamin D3 to enhance human innate immunity against infections through the induction of antimicrobial peptides in a variety of cell types [4, 11].

Recently, we showed for the first time that incorporation of 25(OH)D3 into PCL and PLA nanofiber membranes by electrospinning allowed sustained release over a period of four weeks. Furthermore, co-culture of 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber membranes with keratinocytes and monocytes largely boosted the expression of the endogenous LL-37 production compared to the free drug [12]. Moreover, co-delivery of the pam3CSK4 peptide (a TLR agonist) and 25(OH)D3 from PCL nanofiber sutures could further enhance the production of the LL-37 peptide compared to 25(OH)D3 alone [3]. Finally, using mice that carried the human CAMP gene, we demonstrated that implanting PCL nanofibrous dressings containing 1,25(OH)2D3 induced human CAMP gene expression in the wounds [13]. While these studies demonstrated that we could induce the human CAMP gene in vivo, they do not provide information of the human immune response to these dressings. To begin translating our findings into humans, it is necessary to perform preclinical studies in animal models that mimic the human condition regarding host immune response and endogenous antimicrobial peptide production.

Zebrafish [14], rodents (e.g., mice [15], rat [16]), rabbit [17], and large animals (e.g., swine [18], sheep [19], dog [20]) are used to evaluate host response to biomaterials. However, there are many genetic, biologic, and immunologic differences between humans and these animals [21, 22] indicating that host responses in these animal models may not resemble outcomes in humans. In addition, only a tiny proportion of studies use humans for testing owing to the limited number of patients and strict ethical concerns [23, 24]. The emergence of a mice model carrying the human immune system could address this issue. Humanized mice produced by injecting CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells show robust, long-term multi-lineage engraftment of human immune cell populations [25]. This model has been widely used for studying viral infections, xenogenic transplantations, and autoimmune diseases [25], but only a few studies have examined the host response to xenogeneic and allogeneic decellularized biomaterials in these humanized mice [26, 27]. To date, host response to synthetic biomaterials and drug-eluting synthetic biomaterials remains unexplored using this model.

In an earlier study, we showed for the first time that fabrication of a radially aligned, electrospun nanofiber membrane possessed high potential as a biomedical patch or graft to induce wound closure and tissue regeneration [28]. Nevertheless, the dense structure and small pore size of the 2D nanofiber membrane limited its applications in tissue regeneration. In a recent study, we developed an approach for expanding traditional nanofiber membranes from 2D to 3D with controlled thickness and porosity by depressurization of subcritical CO2 fluid [16]. The expanded 3D nanofiber scaffolds formed layered structures and simultaneously maintained the aligned nanotopographic cues. In addition, the expanded 3D nanofiber scaffolds could significantly promote cellular infiltration and neotissue formation after subcutaneous implantation compared to the traditional nanofiber membranes [16]. Moreover, this method also considerably retained the amount and activity of encapsulated bioactive drugs. In our most recent work, we developed a new approach for generating 3D radially aligned nanofiber scaffolds inspired by the concept of solid of revolution and an innovative gas-foaming technique [29]. In this study, we test the hypothesis that 3D radially aligned nanofiber scaffolds releasing 25(OH)D3 will decrease inflammatory responses and increase antimicrobial peptide expression in the wounds of human immune system-engrafted mice.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

PCL (Mw = 80 kDa), gelatin, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dichloromethane (DCM) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from BDH Chemicals (Dawsonville, GA). 25(OH)D3 and DAPI were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (TX, USA).

2.2. Antibodies

Human nuclei (1:100, Millipore, catalog number: MAB1281), human CD19 (1:250, Abcam, catalog number: ab134114), mouse CD19 (1:50, Bio-Rad, catalog number: MCA1439GA), human CD8 (1:250, Abcam, catalog number: ab93278), mouse CD8 (1:500, Abcam, catalog number: ab217344), human CD4 (1:500, Abcam, catalog number: ab133616), mouse CD4 (1:250, Abcam, catalog number: ab183685), human CD206 (1:100, Santa Cruz, catalog number: sc-376232), mouse CD206 (15 μg/ml, R&D system, catalog number: AF2535), human CCR7 (20 μg/ml, Abcam, catalog number: ab191575), mouse CCR7 (20 μg/ml, Novus Biologicals, catalog number: MAB3477), human TNF-α (1:100, Abcam, catalog number: ab9579), mouse TNF-α (1:200, Abcam, catalog number: ab34674), human IL-6 (1:100, Abcam, catalog number: ab216492), mouse IL-6 (1:50, Abcam, catalog number: ab208113), human IL-4 (0.25μg/ml, Abcam, catalog number: ab9622), mouse IL-4 (1:50, Santa Cruz, catalog number: sc-53084), human IL-10 (1:200, Abcam, catalog number: ab34843), mouse IL-10 (10 μg/ml, Abcam, catalog number: ab183992), human cathelicidin (20 μg/ml, Abcam, catalog number: ab69484), and mouse CAMP (1:100, Novus Biologicals, catalog number: NB100–98689). Goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (FITC) (1:300, Catalog number: ab6717), goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (1:200, Catalog number: ab150113), goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647) (1:200, Catalog number: ab150115), goat anti-rat IgG H&L (Cy5®) (1:400, Catalog number: ab98418), and donkey anti-goat IgG H&L (Cy5®) (1:400, Catalog number: ab97117).

2.3. Humanized mice

The humanized mice used in this study were created as follows. Newborn NOD/SCID/IL2Rγc−/− (NSG, www.jax.org/strain/005557) mice were bred at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC). Animal procedures strictly followed the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols at UNMC and adhered to the Animal Welfare Act and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. P0–1 litters were irradiated with 1 Gy (RS 2000 X-ray Irradiator, Rad Source Technologies, Inc., Suwanee, GA, USA). Pups were intrahepatically injected with 5×104 CD34+ human stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) isolated from umbilical cord blood obtained from Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic at UNMC. Mice blood samples collected from the facial vein were evaluated by flow cytometry starting at 8 weeks post-engraftment to monitor expansion of human leukocytes. Blood cells were reconstituted in a buffer of 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with antibodies against human cell markers including CD45+ fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, BD/555482), CD3+ Alexa Fluor 700 (BD/561805), CD19+ R-phycoerythrin (PE) cyanine 7 (Cy7, BD/555414), CD4+ allophycocyanin (APC, BD/ 561841) for 30 min at 4°C. Samples were analyzed using a BD LSR2 flow cytometer using acquisition software FACS Diva v6 (BD Biosciences, USA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo® analysis software v10.2 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). Gates were assigned according to the appropriate control population. Mice with established human hemato-lymphoid reconstitution (~5 months of age) were used in experiments. The expression of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood of experimental humanized mice ranged from 44.7% to 77.4% (Table S1), which is significantly higher than the standard 25% [30, 31].

2.4. Fabrication of 2D electrospun PCL nanofiber mats

PCL nanofiber mats were produced by electrospinning as described in our previous studies [16, 18]. Briefly, PCL (Mw= 80 kDa) was dissolved in a solvent mixture consisting of DCM and DMF in a ratio of 4:1 (v/v) at a concentration of 10% (w/v). The PCL solution was pumped at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/h using a syringe pump. An electrical potential of 15 kV was applied between the spinneret (a 22-gauge needle) and a grounded collector located 20 cm from the spinneret. The aligned nanofiber mats were collected on a drum with a rotating speed of 2000 rpm. Approximately 1 mm-thick aligned PCL nanofiber mats were collected. Similarly, the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber mat was fabricated by electrospinning 10% PCL solution containing 1 mg/ml 25(OH)D3 [3].

2.5. Fabrication of radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds

PCL nanofiber mats were first cut into 1 mm × 5 mm rectangles in liquid nitrogen to avoid deformation on the edges. The side of the nanofiber mat that is perpendicular to the direction of nanofiber alignment was fixed by thermo-treatment (85°C for 1 s). Next, ~1 g of dry ice and one piece of nanofiber mat were put into a 30 mL Oak Ridge centrifuge tube, and the tube was sealed. After the dry ice transformed into CO2 fluid, we quickly loosened the cap and removed the expanded nanofiber scaffold from the tube [16]. This procedure was repeated until the desired expansion was reached. The expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with and without 25(OH)D3 loading were sterilized with ethylene oxide gas before subcutaneous implantation.

2.6. Subcutaneous implantation of radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds

Briefly, the humanized mice were anesthetized using 4% isoflurane in oxygen for approximately 2 min. Mice were placed on a heating pad to maintain their body temperature. An area of 4 χ 4 cm2 on the back of each animal was shaved, and povidone-iodine solution was applied three times on the exposed skin. Subcutaneous pockets were made (1 cm incisions) on both sides of the dorsum. Each implant was directly inserted into a subcutaneous pocket with tweezers, and the skin incisions were closed with a stapler. Each mouse received 2 implants. Two mice were considered as the treatment group to investigate totally 4 implants for each group. Mice were euthanized with CO2 at 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-implantation. Each explant with the surrounding tissue was gently dissected out of its subcutaneous pocket and then immersed in formalin for at least 3 days before histology analysis. Animal studies were approved by IACUC at UNMC.

2.7. Histological observations

Fixed samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (70%-100%), embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned (5 μm thick). Samples were stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s trichrome stain. For determining the density of newly formed blood vessels, the total blood vessels in each picture captured was counted, and five randomly selected pictures were used to determine the average newly formed blood vessels per millimeter. For quantification of collagen deposition, the percentage of collagen-covered area within the scaffold area was quantified using ImageJ, and five randomly selected pictures were used to determine the average percentage of collagen-covered area within the scaffold area.

2.8. Immunohistochemical analysis

For immunohistochemical staining, slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by antigen retrieval in heated citrate buffer for 5 min (citrate buffer solution, pH 6.0 at 100 °C). Nonspecific antibody binding was prevented with 5% BSA solution. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Then the corresponding secondary antibodies were added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature, followed by staining with DAPI for 5 min. To determine the percentage of infiltrated human immune cells, we counted the total cell nucleus (blue) and human nuclei positive nucleus (red) in each 100 μm2 area, and five randomly selected areas were used to determine the average percentage of human immune cells. The average percentage of human immune cells was calculated using the following equation: Percentage of human immune cells (%) = (human nuclei positive nucleus / all cell nucleus) * 100%. For T cells; B cells; macrophages; and CD31-, cytokine-, and cathelicidin-positive cells, we counted all positive cells in each 100 or 200 μm2 area, and five randomly selected areas were used to determine the average positive cells per mm2.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± S.D., and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences among groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc tests. The values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The values of p<0.01 were considered statistically as highly significant.

3. Results

3.1. Fabrication and characterization of expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading

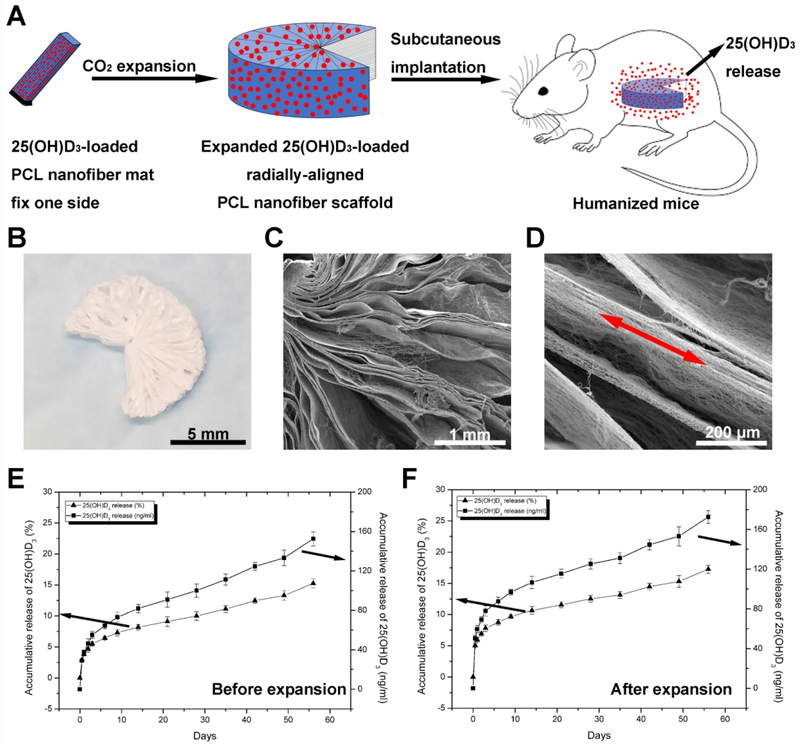

The expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds were obtained by solid of revolution-inspired gas foaming by depressurization of subcritical CO2 fluid (Fig. 1A), which could considerably maintain the amount and bioactivity of the encapsulated 25(OH)D3 [16]. The expanded scaffolds showed the following distribution of angles: 0°-180° (11.43%), 180°-270° (48.57%), and 270°-360° (25.71%); 14.29% of scaffolds expanded completely (360°). In this study, we used radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds that expanded in the range of 180°-360° for drug release and in vivo tests. Figure 1b shows a photograph of a radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffold with an expanded angle in the range of 180°-270°. Fig. 1C and 1D show SEM images of an expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffold shown in Fig. 1B, indicating the scaffold consists of radially aligned nanofibers and gaps between neighboring nanofiber layers. Fig. 1E and 1F show in vitro release profiles of 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber mats before and after expansion, exhibiting a similar initial burst followed by a sustained release over 8 weeks. The percentages of 25(OH)D3 cumulative release after 4 weeks were (10.06 ± 0.68)% and (12.52 ± 0.53)% for 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber mats before and after expansion, respectively. The percentages of 25(OH)D3 cumulative release after 8 weeks were (15.26 ± 0.72)% and (17.39 ± 0.64)% for 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber mats before and after expansion, respectively.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic illustrating the fabrication of 25(OH)D3-loaded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds and their subcutaneous implantation to humanized immune system mice. (B) Photograph of the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds. (C, D) SEM images show the surface structure and fiber alignment of the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds. (E) In vitro release profiles of 25(OH)D3 from PCL nanofiber mats before expansion. (F) In vitro release profiles of 25(OH)D3 from the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds.

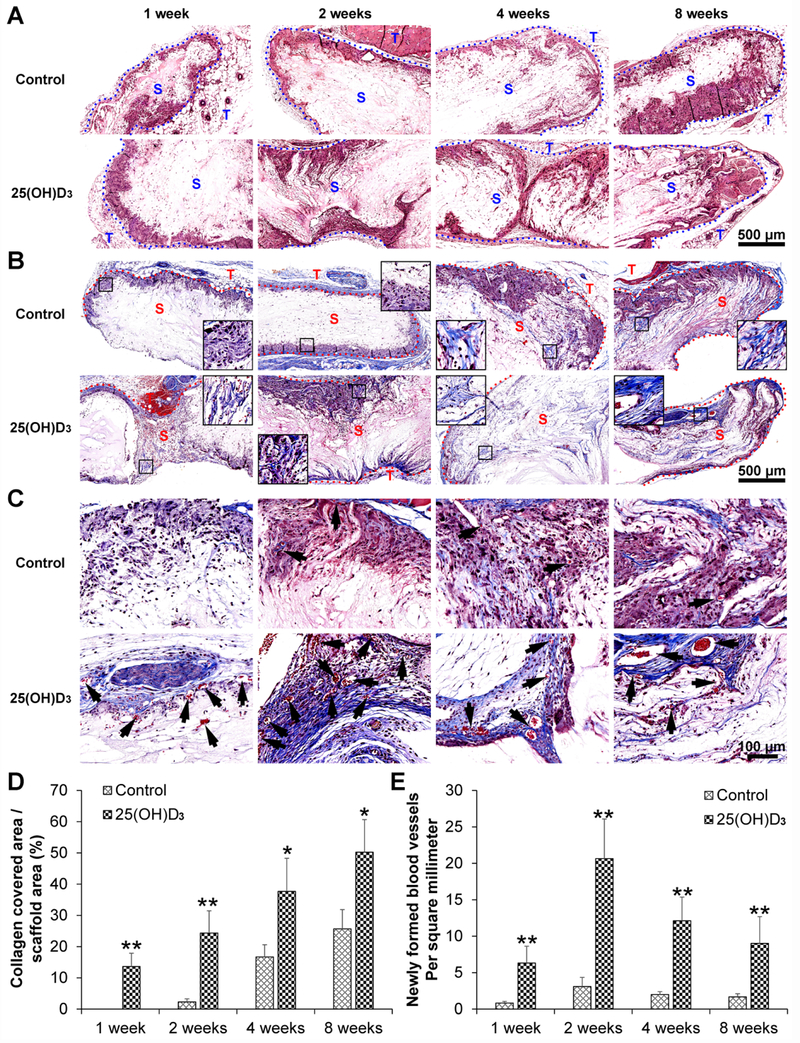

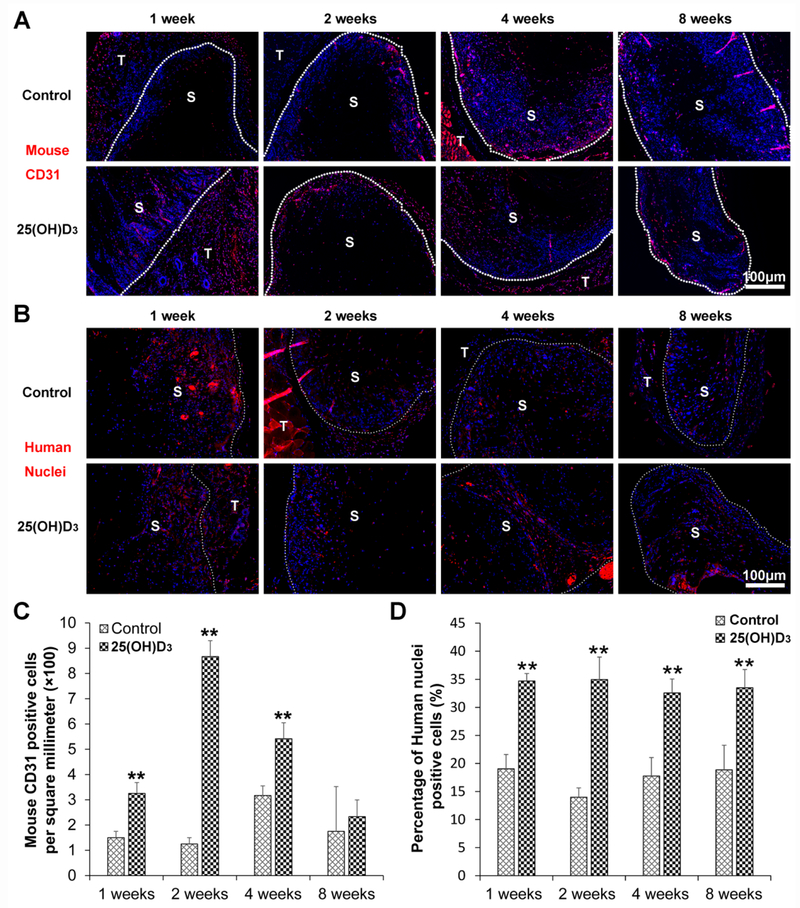

3.2. Cell penetration, collagen deposition, and blood vessel formation

H&E staining shows a similar cell penetration for expanded, radially aligned nanofiber scaffolds without and with containing 25(OH)D3. Cells infiltrated into these scaffolds not only from the top and bottom surfaces but also from all sides (Fig. 2A). More collagen deposition was observed within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading than within scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p<0.01), 2 (p<0.01), 4 (p<0.05), and 8 (p<0.05) weeks. In particular, after 8 weeks of implantation, a large amount of deposited collagen fibers was found within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading (50.23±10.45)% compared to that in scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading (25.67±6.19)% (Fig. 2B and Fig. 2C). Moreover, more new blood vessels indicated by black arrows were observed within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading than within scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p<0.01), 2 (p<0.01), 4 (p<0.01), and 8 (p<0.01) weeks (Fig. 2C and Fig. 2E). In addition, the number of CD31-positive cells within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was higher than that in scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p<0.01), 2 (p<0.01), and 4 (p<0.01) weeks (Fig. 3A and Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

H&E (A) and Masson trichrome (B) staining of harvested expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. (C) Magnified image of (B) showing the new blood vessel formation (indicated by black arrows) within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. S: scaffold area (within the dotted line), T: tissue area (outside the dotted line). The quantification of newly formed blood vessels (D) and collagen deposition (E) within the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber scaffold area or the PCL nanofiber scaffold area (Control) after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. *<0.01, **p < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Mouse CD31 (A) and human immune cell (B) distribution in the harvested expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. S: scaffold area (within the dotted line), T: tissue area (outside the dotted line). Human nuclei were stained with anti-human nuclei antibody in red. The quantification of mouse CD31 (C)- and human nuclei (D)-positive cells within the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber scaffold area (25(OH)D3) or the PCL nanofiber scaffold area (Control) after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. **p < 0.01.

3.3. Human immune cell distribution

Fig. 3B shows human immune cell distribution within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues. The percentages of human immune cells within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds area were (19.05 ± 2.55)%, (13.98 ± 1.67)%, (17.77 ± 3.29)%, and (18.86 ± 4.40)% after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks , respectively (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, the percentages of human immune cells within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading were (34.71 ± 1.33)%, (34.96 ± 1.67)%, (32.58 ± 2.48)%, and (33.49 ± 3.27)% after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks, respectively (Fig. 3B). The percentage of infiltrating human immune cells within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was significantly higher than that in scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading at each indicated time point (p<0.01).

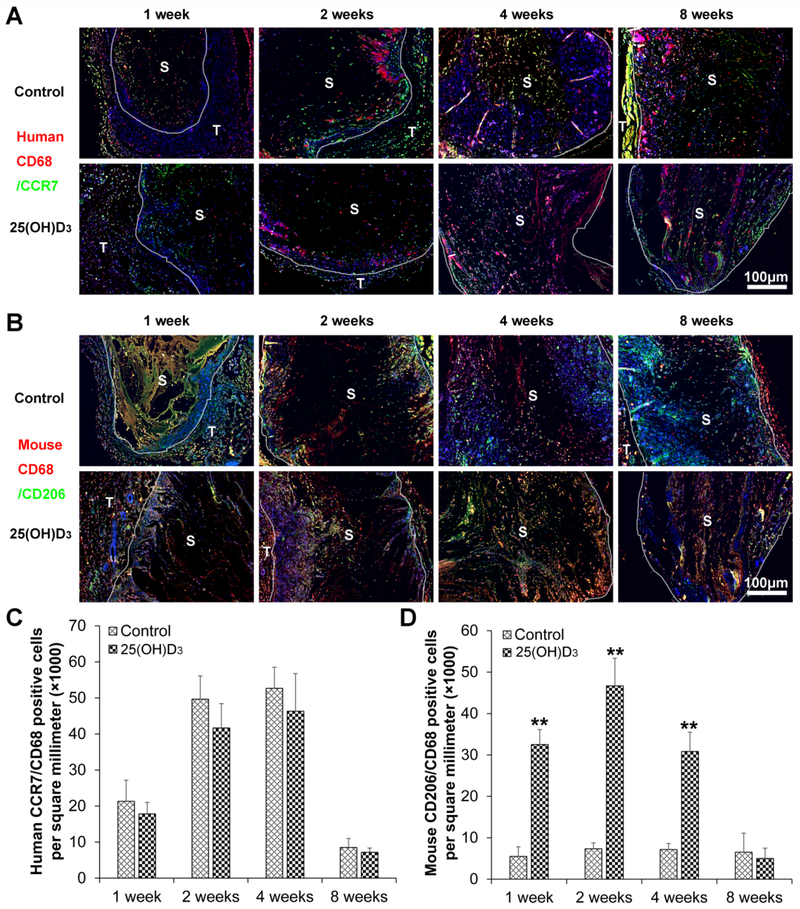

3.4. Human immune cell identification

To identify the cell types, we used a variety of markers including human CD19, CD8, CD4, CD68/CCR7, and /CD68/CD206 for immunohistochemistry staining. The number of CD19 human B cells in expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was higher than that in scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after implantation for 1 week (p<0.01). No human B cells were observed on both expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with and without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 2, 4, and 8 weeks (Fig. S1A and Fig. S2A). The number of human cytotoxic T cells (CD8) within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was lower than that within scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 and 2 weeks (Fig. S1B and Fig. S2B). The number of human T-helper cells (CD4) within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was dramatically higher than that within scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 and 2 weeks (p < 0.01) (Fig. S1C and Fig. S2C). As expected, no mouse B lymphocytes (CD19), cytotoxic T cells (CD8), and T helper cells (CD4) were detected within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with and without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation (data not shown).

Neither human M2-type macrophages (human CD68/CD206) nor mouse M1-type macrophages (mouse CD68/CCR7) were detected in the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation (Fig. S3A and Fig. S3B). The number of mouse M2-type macrophages (mouse CD68/CD206) within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was significantly higher than that within the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, and 4 weeks. No significant difference between these two groups was observed at 8 weeks (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4C). However, there was no statistical difference in the number of human M1-type macrophages (human CD68/CCR7) between the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading and the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading at each indicated time point (Fig. 4B and Fig. 4D). These results were also verified by immunostaining with markers including human CD 163 (M2-type macrophage) and mouse i-NOS (M1-type macrophage) antibodies (Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Human CD68 (red)/CCR7 (green) (A) and mouse CD68 (red)/CD206 (green) (B) immunohistochemical staining of the harvested expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. S: scaffold area (within the dotted line), T; tissue area (outside the dotted line). The quantification of human CD68/CCR7 (C)- and mouse CD68/CD206 (D)-positive cells within the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber scaffold area (25(OH)D3) or the PCL nanofiber scaffold area (Control) after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

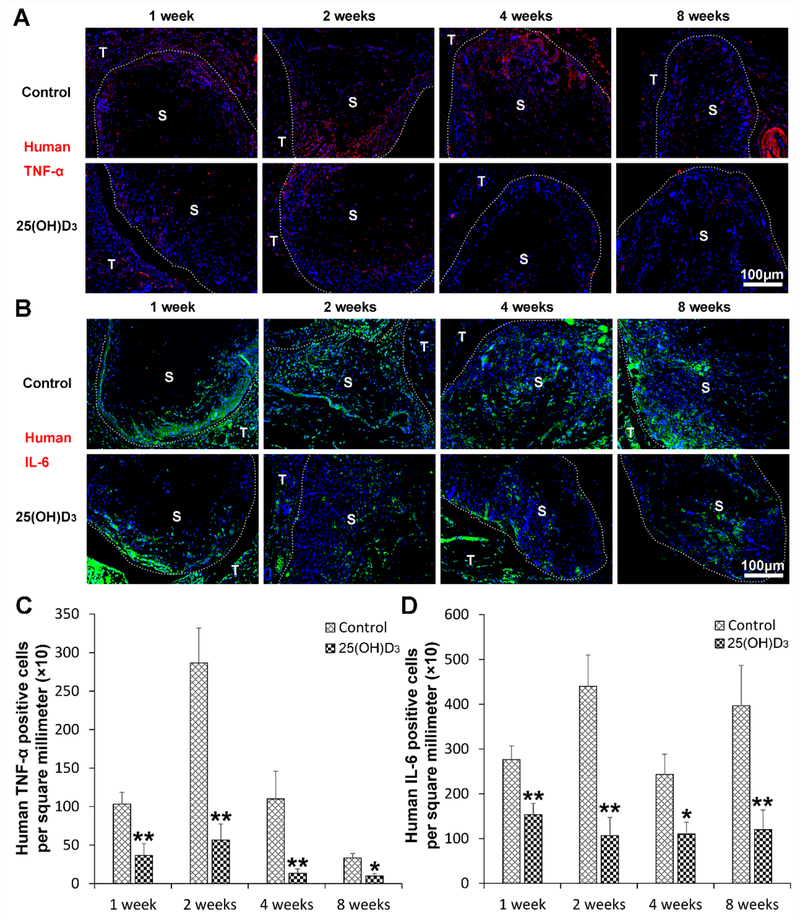

3.5. Human proinflammatory cytokine expression

To examine the influence of the eluted 25(OH)D3 from scaffolds on inflammation, human pro-inflammatory cytokine markers including TNF-α and IL-6 were stained by immunohistochemistry. Fig. 5A and Fig. 5C show human TNF-α staining in red, indicating that the expression of human TNF-α within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was significantly lower than that within the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p < 0.01), 2 (p < 0.01), 4 (p < 0.01), and 8 (p < 0.05) weeks. Similarly, Fig. 5B and Fig. 5D show that the expression of human IL-6 within expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was largely reduced compared to that in the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p < 0.01), 2 (p < 0.01), 4 (p < 0.05), and 8 (p < 0.01) weeks (Fig. 5B and Fig. 5D). In addition, the expression of mouse TNF-α and IL-6 shows a similar trend as human TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. S5).

Fig. 5.

Human TNF-α (A) and IL-6 (B) immunohistochemical staining of the harvested expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. S: scaffold area (within the dotted line), T; tissue area (outside the dotted line). The quantification of human TNF-α (C)- and IL-6 (D)-positive cells within the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber scaffold area (25(OH)D3) or the PCL nanofiber scaffold area (Control) after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

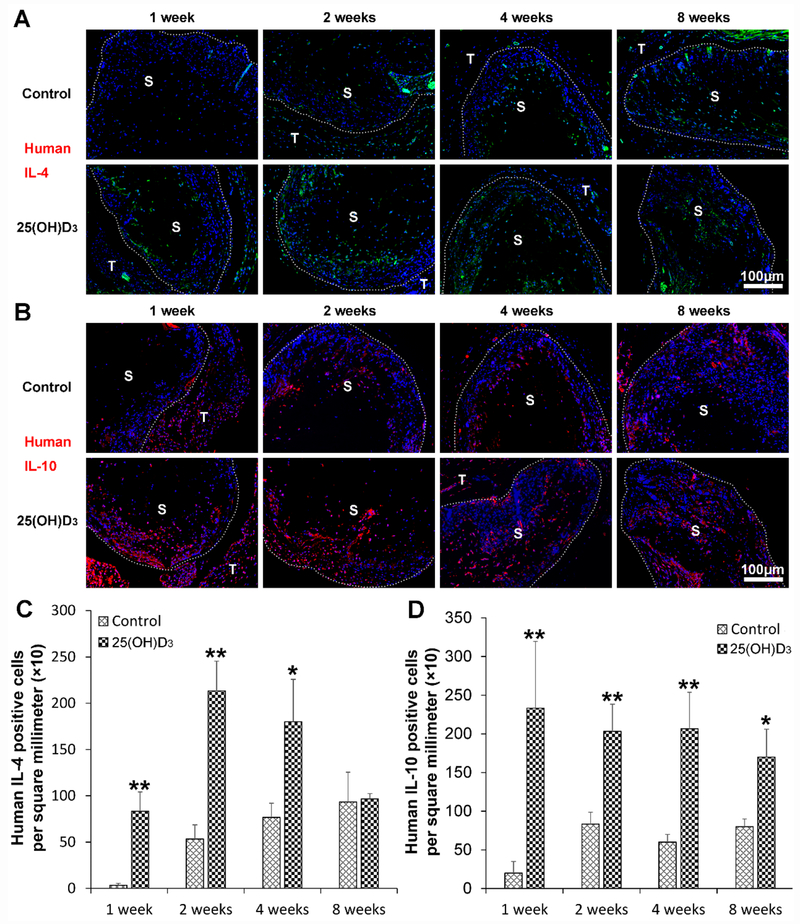

3.6. Human anti-inflammatory cytokine expression

The expression of human anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-4 and IL-10 was examined. Fig. 6A and Fig. 6C show the staining of human IL-4 in green, indicating higher expression of human IL-4 within the radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading than the scaffolds without incorporation of 25(OH)D3 after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p < 0.01), 2 (p < 0.01), and 4 (p < 0.05) weeks. There was no significant difference in human IL-4 expression between the two groups after subcutaneous implantation for 8 weeks. Similarly, the expression of human IL-10 within the radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading was significantly increased compared to that in the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading after subcutaneous implantation for 1 (p < 0.01), 2 (p < 0.01), 4 (p < 0.01), and 8 (p < 0.05) weeks (Fig. 6B and Fig. 6D). In addition, the expression of mouse IL-4 and IL-10 shows a similar trend as human TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. S6).

Fig. 6.

Human IL-4 (A) and IL-10 (B) immunohistochemical staining of the harvested expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. S: scaffold area (within the dotted line), T; tissue area (outside the dotted line). The quantification of human IL-4 (C) and mouse IL-10 (D)-positive cells within the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber scaffold area (25(OH)D3) or the PCL nanofiber scaffold area (Control) after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. *p <0.05, **p < 0.01.

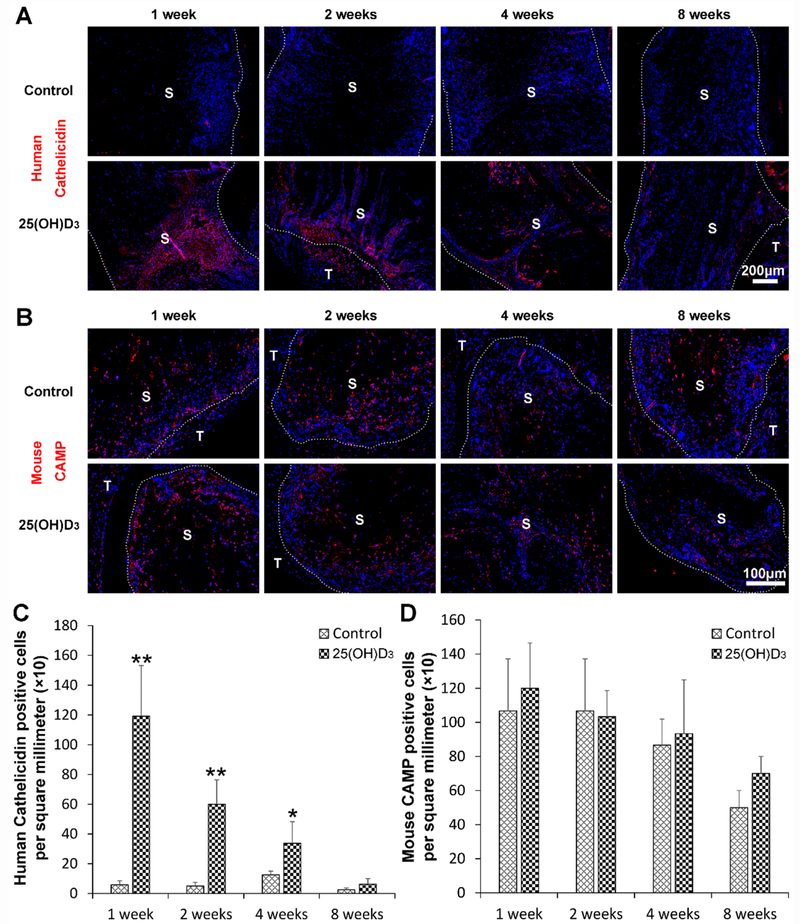

3.7. Human cathelicidin expression

To examine the effect of eluted 25(OH)D3 from scaffolds on production of antimicrobial peptides, the staining of human cathelicidin LL-37/hCAP-18 and mice cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) was performed. Fig. 7A and Fig. 7C show human cathelicidin and mouse CRAMP staining in red. No human cathelicidin expression was detected within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading at each indicated time point. However, there was a significant amount of human cathelicidin expression within 25(OH)D3-loaded scaffolds. It is seen that the expression of human cathelicidin gradually decreased from week 1 to week 8 post-implantation. In comparison, mouse CRAMP was expressed similarly within the expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with and without 25(OH)D3 loading. There was no difference in the CRAMP expression between these two groups at each indicated time point (Fig. 7B and Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

(A) The human cathelicidin immunohistochemical staining of the harvested expanded, radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds without and with 25(OH)D3 loading and their surrounding tissues after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. S: scaffold area (within the dotted line), T; tissue area (outside the dotted line). (B) The quantification of human cathelicidin-positive cells within the 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber scaffold area (25(OH)D3) or the PCL nanofiber scaffold area (Control) after subcutaneous implantation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. *p <0.05, **p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

Implantable medical devices play a critical role in the practice of modern medicine; however, medical devices are often plagued by various complications including fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and infection, which may lead to implant failure [1, 2]. To eliminate these complications, different strategies have been developed to improve the function of implants. In this study, we showed that the 25(OH)D3-eluting expanded, radially aligned nanofiber scaffolds could potentially address the above complications associated with implants.

The loading efficiency of 25(OH)D3 is (76 ± 7.4)%, which was measured following our previous work [12]. The drug release profiles could be determined by the rates of water penetration into nanofiber mats or expanded nanofiber scaffolds, water penetration into nanofibers, drug dissolution, drug diffusion through nanofibers, and drug desorption from nanofibers. The slow release rate of 25(OH)D3 could be mainly attributed to the slow rates of dissolution and water penetration owing to its low water solubility and hydrophobicity of PCL nanofibers [3, 12]. The structure of nanofiber scaffolds could have marginal influence on the release profiles. This is the reason why there is no significant difference in the cumulative release of 25(OH)D3 from 25(OH)D3-loaded PCL nanofiber mats before and after expansion.

Studies have shown that the porosity and pore size of scaffolds/implants could be critical for cellular infiltration and foreign body response (i.e., fibrosis) [32, 33]. Our recent study demonstrated an innovative gas-foaming technique by depressurization of subcritical CO2 fluid to expand traditional 2D nanofiber membranes into the third dimension with well-controlled thickness and porosity [16]. The expanded scaffolds had several unique features including nanofibrous morphology, superelastic property, shape-recovery, and ease of incorporation of bioactive agents [18]. Our most recent study demonstrated the fabrication of 3D nanofiber scaffolds with complex shapes inspired by the solid of revolution concept and the gas-foaming technique [29]. The obtained nanofiber scaffolds consisting of radially aligned nanofibers and gaps/pores between neighboring layers allowed faster cellular infiltration, collagen deposition, and new blood vessel formation than the scaffolds expanded along one direction [16]. The rapid cell penetration and neovascularization attributed to the highly porous structure could enhance the integration of nanofiber scaffolds with the surrounding tissues and regenerate neotissues instead of forming a fibrotic capsule on the surface of the scaffolds. Moreover, this method facilitates the encapsulation of 25(OH)D3 and largely retains its amount and bioactivity as the expansion process is conducted at low temperatures in a nonaqueous solution [29].

The infiltrating human immune cells mainly consisted of cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) and M1-type macrophages (CCR7+, i-NOS+) on radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with and without 25(OH)D3 loading, especially after 1 week and 2 weeks post-implantation. In contrast, the infiltrating mouse macrophages were mainly of the M2 type (CD206+, CD163+). A lower number of human cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) and a higher number of T-helper cells (CD4+) were observed within radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading than within the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading. This suggests that the host considers the radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds as a foreign object after subcutaneous implantation, thereby resulting in an increase in the number of infiltrating cytotoxic T cells (CD8+). In contrast, the 25(OH)D3-eluting scaffolds reduced the foreign body response by inhibiting the infiltration of cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) [34], which is consistent with the immunosuppressive properties of 1,25(OH)2D3 [35].

Studies in vitro, in animals, and in patients administered free drug systemically, suggest that vitamin D3 reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while increasing the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines [5, 36, 37]. In addition, vitamin D deficiency is associated with early implant failure [38, 39]. Zhang et al. reported that 25(OH)D3 inhibits the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α from LPS-induced monocytes/macrophages by upregulation of MAPK phosphatase-1 expression and suppression of p38 activation [5]. This inhibitory effect was dependent on the concentration of 25(OH)D3, as it suppressed IL-6 and TNF-α production in human monocytes only when its concentration was ≥30 ng/ml, a level in blood that is considered sufficient for humans [4, 5]. In a separate study, Boonstra et al. showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited type 1 T-helper cell development and cytokine production and resulted in type 2 T-helper cell expansion and an increase in IL-4 production [40]. Mahon et al. further confirmed IL-4 was the only cytokine, which increased following 1,25(OH)2D3 addition, and only in type 2 T-helper cells [41]. Wöbke et al. showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 was able to upregulate the expression of IL-10 in monocytes and dendritic cells [42]. In addition, 1,25(OH)2D3 was also capable of enhancing IL-10 production in T regulatory cells [43]. Moreover, a quantitative study showed IL-10 production in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice model, indicating that the plasma IL-10 levels in the vitamin D-supplemented group (26.28 ± 0.42 pg/ml) were much higher than those in the vitamin D-deficient group (16.45 ± 1.58 pg/ml) [44]. The anti-inflammatory effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 are also likely mediated by the induction of IL-10-producing regulatory T-cells (Tregs) [45]. Patients undergoing renal transplant who received systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 experienced an expansion of circulating Treg cells [46]. Interestingly, 25(OH)D3 is processed to 1,25(OH)2D3 by dendritic cells and T-cells in the skin, and this could signal T-cells to migrate to the epidermis [47].

The local delivery of25(OH)D3 for reducing inflammatory responses has not been studied extensively. In this work, we demonstrated that topical delivery of 25(OH)D3 from nanofiber scaffolds was capable of decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6) and increasing the expression of antiinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4 and IL-10) in both mice and humans. Based on the release profiles, the concentration of 25(OH)D3 could reach (50.31 ± 4.60) ng/ml after incubation for 12 h, which is significantly higher than 30 ng/ml [5, 37]. By 1 week, the concentration of 25(OH)D3 reached 100 ng/ml or 240 nM in culture (Fig. 1). At this concentration, 25(OH)D3 can act as a ligand for the VDR, and the activation of macrophages and dendritic cells by the implantation of the scaffold could result in the synthesis of significant levels of 1,25(OH)2D3. Increased VDR signaling is reflected by the reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and the increased number of T-helper cells and expression of IL-4 within the expanded, radially aligned nanofiber scaffolds with 25(OH)D3 loading as compared to those within the scaffolds without 25(OH)D3 loading. However, there was technical difficulty in collecting enough local tissues to extract sufficient amount of proteins for ELISA measurement. Even after 8 weeks of subcutaneous implantation, the scaffolds were only surrounded by a very thin layer of tissue. RNAscope analysis will be considered in our future studies. Yet, it will be quantitative more than the already used methodology.

The traditional strategy for preventing infections of implanted medical devices is to incorporate antibiotics or silver-related products [48, 49]. However, this strategy may select for drug resistance and/or raise toxicity concerns [50, 51]. Modulating the host immune response could promote attack of the pathogen on numerous fronts rather than a single front like traditional antibiotics, thus limiting the selection of drug-resistant bacteria. Studies have shown that vitamin D3 plays an important role in both innate and adaptive immunity [52]. The 25(OH)D3-eluting nanofiber scaffolds developed in this work could represent a new approach to prevent infections of implants. Regulation of CAMP gene expression by vitamin D3 does not occur in other mammals [53]. It is both human and non-human primate-specific [53]. By using human immune system-engrafted mice, we could examine human-specific responses including induction of cathelicidin LL-37 expression. As expected, no LL-37 expression was detected within scaffolds lacking 25(OH)D3, but a significant amount of LL-37 expression was observed within the 25(OH)D3-eluting nanofiber scaffolds. It has been demonstrated that the increased levels of 25(OH)D3 result in an increase in the production of the cathelicidin protein [3, 12]. However, the presented data showed that the expression of cathelicidin LL-37 gradually decreased from week 1 to week 8 post-implantation. There are probably two reasons that cause reduction in cathelicidin expression. One is that the actual amount of released 25(OH)D3 gradually decreased from week 1 to week 8. The other is that the activity of released 25(OH)D3 could be compromised after implantation for 8 weeks. We predict that this induction could potentially prevent infections. The anti-inflammatory response and endogenous production of cathelicidin LL-37 could be further enhanced by replacing 25(OH)D3 with the active form of vitamin D - 1,25(OH)2D3. Moreover, 25(OH)D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 in combination with other immune-modulating compounds (e.g., a TLR agonist or CYP24A1 inhibitor) may further boost these effects compared to nanofibers loaded with 25(OH)D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 alone [3].

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have investigated the human immune system response to 25(OH)D3-eluting radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds in mice engrafted with CD34+ HSPCs isolated from umbilical cord blood. The histological observations revealed that the highly porous structure of the scaffolds promoted rapid cellular infiltration, collagen deposition, and new blood vessel formation. Immunofluorescence staining results showed the local delivery of 25(OH)D3 from radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds significantly reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-6 expression, while increasing the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-4 and IL-10 after subcutaneous implantation compared to pristine scaffolds. Furthermore, the local delivery of 25(OH)D3 from nanofiber scaffolds also enhanced the human cathelicidin LL-37 production at or near the implantation site. Together, the strategies developed in this study could be applied to improve the failure rate of current medical devices and engineer 3D scaffolds/tissue constructs for modulating immune response in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Transplant failure of medical devices, grafts, scaffolds, and tissue-engineered constructs due to inflammation and infection causes not only economic losses but also sufferings of second operation to the patient. Positive modulation of the host response to implants, scaffolds, and tissue-engineered constructs is likely to reduce the failure rate. Vitamin D3 plays an important role in modulating the immune response. It is able to not only reduce inflammation and induce endogenous antimicrobial peptide production but also prevent multidrug resistance and other side effects of traditional antibiotics. In this study, host responses to 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3)-eluting radially aligned PCL nanofiber scaffolds were evaluated in human immune system-engrafted mice. The 25(OH)D3-eluting medical devices or scaffolds were able to modulate positive immune response and promote antimicrobial peptide production. This work presented an innate immunity-enhancing approach for reducing the inflammatory response and preventing infections, likely resulting in improvement of success rates of implants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partially from startup funds from the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01GM123081 and 1U54GM115458. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference

- [1].Franz S, Rammelt S, Scharnweber D, Simon JC, Immune responses to implants–a review of the implications for the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials, Biomaterials 32(2011)6692–6709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yanez M, Blanchette J, Jabbarzadeh E, Modulation of Inflammatory Response to Implanted Biomaterials Using Natural Compounds, Curr. Pharm. Des. 23(2017)6347–6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen S, Ge L, Gombart AF, Shuler FD, Carlson MA, Reilly DA, Xie J, Nanofiber-based sutures induce endogenous antimicrobial peptide, Nanomedicine (Lond.) 12(2017)2597–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hewison M, Antibacterial effects of vitamin D, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 7(2011)337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang Y, Leung DYM, Richers BN, Liu Y, Remigio LK, Riches DW, Goleva E, Vitamin D inhibits monocyte/macrophage proinflammatory cytokine production by targeting MAPK phosphatase-1, J. Immunol. (2012)1102412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, Ochoa MT, Schauber J, Wu K, Meinken C, Kamen DL, Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response, Science 311(2006)1770–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP, Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly upregulated in myeloid cells by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 19(2005)1067–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Weber G, Vitamin D induces the antimicrobial protein hCAP18 in human skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 124(2005)1080–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, Tavera-Mendoza L, Lin R, Hanrahan JW, Mader S, White JH, Cutting edge: 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J. Immunol. 173(2004)2909–2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yuk JM, Shin DM, Lee HM, Yang CS, Jin HS, Kim KK, Lee ZW, Lee SH, Kim JM, Jo EK. Vitamin D3 induces autophagy in human monocytes/macrophages via cathelicidin. Cell Host Microbe 6(2009)231–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gombart AF, Saito T, Koeffler HP. Exaptation of an ancient Alu short interspersed element provides a highly conserved vitamin D-mediated innate immune response in humans and primates. BMC genomics 10(2009)321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jiang J, Chen G, Shuler FD, Wang CH, Xie J, Local sustained delivery of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 for production of antimicrobial peptides, Pharm. Res. 32(2015)2851–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jiang J, Zhang Y, Indra AK, Ganguli-Indra G, Le MN, Wang H, Hollins RR, Reilly DA, Carlson MA, Gallo RL, Gombart AF. 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-eluting nanofibrous dressings induce endogenous antimicrobial peptide expression. Nanomedicine (Lond). 13(2018)1417–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Romero-Sánchez LB, Marí-Beffa M, Carrillo P, Medina MÁ, Díaz-Cuenca A, Copper-containing mesoporous bioactive glass promotes angiogenesis in an in vivo zebrafish model, Acta Biomater. 68(2018)272–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jiang J, Zhang Y, Indra AK, Ganguli-Indra G, Le MN, Wang H, Hollins RR, Reilly DA, Carlson MA, Gallo RL, Gombart AF, Xie J, 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-eluting nanofibrous dressings induce endogenous antimicrobial peptide expression, Nanomedicine (Lond.) 13(2018)1417–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jiang J, Chen S, Wang H, Carlson MA, Gombart AF, Xie J, CO2-expanded nanofiber scaffolds maintain activity of encapsulated bioactive materials and promote cellular infiltration and positive host response, Acta Biomater. 68(2018)237–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Khorsand B, Nicholson N, Do AV, Femino JE, Martin JA, Petersen E, Guetschow B, Fredericks DC, Salem AK, Regeneration of bone using nanoplex delivery of FGF-2 and BMP-2 genes in diaphyseal long bone radial defects in a diabetic rabbit model, J. Control. Release 248(2017)53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen S, Carlson MA, Zhang YS, Hu Y, Xie J, Fabrication of injectable and superelastic nanofiber rectangle matrices (“peanuts”) and their potential applications in hemostasis, Biomaterials 179(2018)46–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ahmed M, Hamilton G, Seifalian AM, The performance of a small-calibre graft for vascular reconstructions in a senescent sheep model, Biomaterials 35(2014)9033–9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Imperiale JC, Nejamkin P, del Sole MJ, Lanusse CE, Sosnik A, Novel protease inhibitor-loaded Nanoparticle-in-Microparticle Delivery System leads to a dramatic improvement of the oral pharmacokinetics in dogs, Biomaterials 37(2015)383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mestas J, Hughes CCW, Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology, J. Immunol. 172(2004)2731–2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hackam DG , Redelmeier DA , Translation of research evidence from animals to humans , JAMA 296(2006)1727–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zelen CM, Serena TE, Snyder RJ, A prospective, randomised comparative study of weekly versus biweekly application of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft in the management of diabetic foot ulcers, Int. Wound J. 11(2014)122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lavery LA, Fulmer J, Shebetka KA, Regulski M, Vayser D, Fried D, Kashefsky H, Owings TM, Nadarajah J, The efficacy and safety of Grafix® for the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a multi‐centre, controlled, randomi sed, blinded, clinical trial, Int. Wound J. 11(2014)554–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL, Humanized mice in translational biomedical research, Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7(2007)118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang RM, Johnson TD, He J, Rong Z, Wong M, Nigam V, Behfar A, Xu Y, Christman KL, Humanized mouse model for assessing the human immune response to xenogeneic and allogeneic decellularized biomaterials, Biomaterials 129(2017)98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang RM, He J, Xu Y, Christman KL, Humanized mouse model for evaluating biocompatibility and human immune cell interactions to biomaterials, Drug Discov. Today Dis. Models (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xie J, MacEwan MR, Ray WZ, Liu W, Siewe DY, Xia Y, Radially aligned, electrospun nanofibers as dural substitutes for wound closure and tissue regeneration applications, ACS nano 4(2010)5027–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen S, Wang H, Yan Z, Kim HJ, Carlson MA, Xia Y, Xie J, Solids of revolution-inspired, 3D hierarchical assembly of nanofibers with controlled orientations for regenerative medicine, Adv. Mater. 2018. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Manocha GD, Floden AM, Puig KL, Nagamoto-Combs K, Scherzer CR, Combs CK. Defining the contribution of neuroinflammation to Parkinson’s disease in humanized immune system mice, Mol. Neurodegener. 12(2017)17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang M, Yao LC, Cheng M, Cai D, Martinek J, Pan CX, Shi W, Ma AH, De Vere White RW, Airhart S, Liu ET, Humanized mice in studying efficacy and mechanisms of PD-1-targeted cancer immunotherapy, FASEB J. 16(2017)1537–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Taniguchi N, Fujibayashi S, Takemoto M, Sasaki K, Otsuki B, Nakamura T, Matsushita T, Kokubo T, Matsuda S, Effect of pore size on bone ingrowth into porous titanium implants fabricated by additive manufacturing: an in vivo experiment, Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 59(2016)690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Birkenhauer V, Junge K, Conze J, Schumpelick V, Impact of polymer pore size on the interface scar formation in a rat model, J. Surg. Res. 103(2002)208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sarkar S, Hewison M, Studzinski GP, Li YC, Kalia V, Role of vitamin D in cytotoxic T lymphocyte immunity to pathogens and cancer, Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 53(2016)132–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lemire JM, Archer DC, Beck L, Spiegelberg HL, Immunosuppressive actions of 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: preferential inhibition of Th1 functions, J. Nutr. 125(1995)1704S–1708S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Barker T, Martins TB, Hill HR, Kjeldsberg CR, Dixon BM, Schneider ED, Henriksen VT, Weaver LK, Vitamin D sufficiency associates with an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines after intense exercise in humans, Cytokine 65(2014)134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Topilski I, Flaishon L, Naveh Y, Harmelin A, Levo Y, Shachar I, The anti-inflammatory effects of 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on Th2 cells in vivo are due in part to the control of integrin‐mediated T lymphocyte homing, Eur. J. Immunol. 34(2004)1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fretwurst T, Grunert S, Woelber JP, Nelson K, Semper-Hogg W, Vitamin D deficiency in early implant failure: two case reports, Int. J. Implant Dent. 2(2016)24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mengatto CM, Mussano F, Honda Y, Colwell CS, Nishimura I, Circadian rhythm and cartilage extracellular matrix genes in osseointegration: a genome-wide screening of implant failure by vitamin D deficiency, PloS one 6(2011)e15848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Boonstra A, Barrat FJ, Crain C, Heath VL, Savelkoul HFJ, O’Garra A, 1α, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 has a direct effect on naive CD4+ T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells, J. Immunol. 167(2001)4974–4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mahon BD, Wittke A, Weaver V, Cantorna MT, The targets of vitamin D depend on the differentiation and activation status of CD4 positive T cells, J. Cell. Biochem. 89(2003)922–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wöbke TK, Sorg BL, Steinhilber D, Vitamin D in inflammatory diseases, Front. Physiol. 5(2014)244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chambers ES, Hawrylowicz CM, The impact of vitamin D on regulatory T cells, Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 11(2011)29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yang HF, Zhang ZH, Chang ZQ, Tang KL, Lin DZ, Xu JZ, Vitamin D deficiency affects the immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Clin. Exp. Med. 13(2013)265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Barrat FJ, Cua DJ, Boonstra A, Richards DF, Crain C, Savelkoul HF, de Waal-Malefyt R, Coffman RL, Hawrylowicz CM, O’Garra A. In vitro generation of interleukin 10–producing regulatory CD4+ T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)–and Th2-inducing cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 195(2002)603–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ardalan MR, Maljaei H, Shoja MM, Piri AR, Khosroshahi HT, Noshad H, Argani H. Calcitriol started in the donor, expands the population of CD4+ CD25+ T cells in renal transplant recipients. Transplant. Proc. 39(2007)951–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sigmundsdottir H, Pan J, Debes GF, Alt C, Habtezion A, Soler D, Butcher EC. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to’program’T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nature Immunol. 8(2007)285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fullenkamp DE, Rivera JG, Gong YK, Lau KHA, He L, Varshney R, Messersmith PB, Mussel-inspired silver-releasing antibacterial hydrogels, Biomaterials 33(2012)3783–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Campoccia D, Montanaro L, Speziale P, Arciola CR, Antibiotic-loaded biomaterials and the risks for the spread of antibiotic resistance following their prophylactic and therapeutic clinical use, Biomaterials 31(2010)6363–6377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Johnston HJ, Hutchison G, Christensen FM, Peters S, Hankin S, Stone V, A review of the in vivo and in vitro toxicity of silver and gold particulates: particle attributes and biological mechanisms responsible for the observed toxicity, Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 40(2010)328–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Heuer H, Krögerrecklenfort E, Wellington EMH, Egan S, Van Elsas JD, Van Overbeek L, Collard JM, Guillaume G, Karagouni AD, Nikolakopoulou TL, Smalla K, Gentamicin resistance genes in environmental bacteria: prevalence and transfer, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42(2002)289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Adams JS, Hewison M, Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 4(2008)80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Gombart AF, The vitamin D–antimicrobial peptide pathway and its role in protection against infection, Future Microbiol. 4(2009)1151–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.