Abstract

Introduction

Both short and long sleep have been associated with higher mortality. However, most studies are conducted in predominantly white or Asian populations and little is known about the sleep-mortality relationship in blacks. Given the high prevalence of short and long sleep in blacks, it is important to examine the health effects of sleep in this population.

Methods

We studied sleep duration in relation to all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality in 55,375 participants age 40–79 at enrollment in the Southern Community Cohort Study, of whom ~2/3 are black. Weekday and weekend sleep durations were self-reported. Mortality follow up started at baseline (2002–2009) and was regularly updated until 2015 via linkage to Social Security Administration and the National Death Index. We used Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for multiple covariates to estimate relative risks associated with sleep duration.

Results

We found U-shaped relationships between weekday and weekend sleep duration and all-cause mortality, with the effects stronger in whites than blacks. Risks for all-cause mortality were significantly elevated by about 25% among whites and about 10% among blacks reporting either less than 5 hours or more than 9 hours of sleep compared with those reporting 8 hours of sleep. The associations among whites but not blacks were even stronger for cardiovascular disease mortality, whereas no association between sleep duration and cancer mortality was found in either group.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that short and long sleep durations may be weaker predictors of total and cardiovascular mortality in blacks than in whites.

Keywords: sleep, mortality, cancer mortality, cardiovascular mortality, African Americans, health disparity

Introduction

Sleep is a fundamental activity of everyday life and an important determinant of human health. Both short (typically defined as < 7 hours) and long sleep durations (typically defined as ≥ 9 hours) have been found to be important risk factors for a wide range of disease outcomes, including cardiometabolic diseases, mental disorders, cancer, and all-cause mortality.1–5 In the United States, there are considerable differences in sleep duration across racial and ethnic groups, with the prevalence of short and long sleep substantially higher among blacks when compared to whites.6–10 Due to the important health implications of adequate sleep and the well-documented racial differences in sleep duration, it has been hypothesized that sleep disparities could be a fundamental contributor to black-white disparities in various health outcomes in the US.11,12

There is a persistent gap in mortality between black and white Americans. According to the most recent national vital statistics, the black-white gap in life expectancy at age 40 is 3 years for men and 2.1 years for women (black men: 35.8 years, white men: 38.8 years; black women, 40.5 years, white women, 42.6 years).13 Cardiovascular and cancer deaths are among the leading contributors of the black-white gap in life expectancy, together accounting for more than 50% of the observed racial differences (cardiovascular death, 32.2% for men and 43.2% for women; cancer, 16.4% for men and 13.7% for women).14 Mounting evidence suggests that sleep duration may be an important predictor of mortality, and several meta-analysis studies consistently reported a U-shaped association between sleep duration and mortality in adults, with both short and long sleep associated with higher mortality, particularly cardiovascular mortality.4,15,16 However, most of the previous studies on sleep and mortality were conducted in predominantly white and Asian populations, and relatively little is known about the relationship between sleep duration and mortality in blacks. Only one previous study examined race/ethnic-specific relationship between sleep duration and mortality risk in the Multiethnic Cohort Study, and the sleep-mortality relationship appeared to be weaker in black Americans than whites: the study found <7 hours of sleep was not associated with mortality and 9+ hours of sleep was associated with a modest 17% increase in mortality risk in blacks.17

We investigated the association between sleep duration and all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality in blacks as well as whites in the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS), a prospective cohort of a racially diverse and predominantly low income populations in US. To investigate potential racial differences in the sleep-mortality relationship, we directly compared the results among blacks to those among whites in this cohort.

Methods

Study Population

The SCCS is a prospective study investigating health disparities in chronic diseases in white and black adults in 12 southeastern states in the US (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia). Details of the study have been previously reported.18 Briefly, ~ 85,000 men and women (age 40 – 79) were recruited between 2002 and 2009, and two thirds of the baseline cohort are black. The majority of the participants (86%) were enrolled from 71 Community Health Centers (CHC), which provide basic health and preventive services mainly to low income, underinsured and uninsured persons. Additional study participants (14%) were recruited by mailed questionnaires sent to stratified random samples of the general populations of these same states. Informed consent was obtained from each participant upon enrollment into the SCCS. Training of Community Health Center interviewers to administer in-person baseline questionnaires was conducted by SCCS staff. Interviewers were trained to deliver questions in a standardized manner so that each participant would receive the same question wording. Responses to participant inquiries were also standardized so that questions were handled consistently. During periodic reviews of interviews, deviations from these procedures were flagged and further review was conducted. Based on observations of additional interviews, further discussions with interviewers, and discussions with participants some cases were flagged for exclusion. Institutional Review Boards at Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN) and Meharry Medical College (Nashville, TN) approved the study.

Of the 84,513 participants who completed the baseline questionnaire, we excluded those whose questionnaire data did not meet the quality control criteria and were flagged for exclusion (N=1,023), who had missing sleep information (N=1,419) or reported extreme sleep duration (<3 hr or >12 hr) on either weekday or weekends (N=2,981). We further excluded those who had a history of major chronic conditions at baseline, including cancer (N=6,629), cardiovascular disease (N=8,845), Parkinson’s disease (N=57), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (N=4,932), and HIV/AIDS (N=867). We further excluded those who reported to be neither black nor white. The final analytic cohort included 55,375 men and women.

Assessment of Sleep

At baseline, participants reported how many hours (in full hours) they typically slept in a 24-hour period, on weekdays and weekends separately. For our main analysis, we grouped weekday and weekend sleep duration into 7 categories: <5, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10+ hours and we used 8 hours (the largest group) as the reference. For analysis of cause-specific mortality, we grouped sleep duration into four categories (<6, 6, 7–8, 9+ hours) to preserve statistical power and we chose 7–8 hour group as the reference.

Mortality

Vital status was ascertained from the Social Security Administration (SSA) and cause of death was determined via linkage to the National Death Index (NDI) through December 31, 2015. The endpoints of our analysis were all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes I00-I99) and cancer mortality (C00-C79).

Covariates

The baseline questionnaire collected comprehensive information on sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, household income, marital status and employment status. Participants also reported height and weight, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, alcohol drinking, smoking, and medical history of chronic diseases.

Statistical analysis

To determine the relationship between sleep duration categories and mortality risks in white and black populations, we used Cox proportional hazards model to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 2-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI). Person-years of follow-up time were calculated from the baseline until the date of death, or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2015), whichever came sooner. To control for potential confounders, we considered a series of models. In the basic model, we controlled for age (continuous) and sex (male, female). In a second model, we included variables that are potential confounders, including education (less than high school, high school, vocational training or some college, college or higher), household income (<$15,000, $15,000-<$25,000, $25,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000), marital status (Married, separated, divorced or widowed, never married), and employment status (yes, no). We consider results from this model as our main findings. In a third model, we further adjusted for mortality risk factors that may be mediators of the sleep-mortality relationship. These include lifestyle factors that have a bidirectional relationship with sleep, including smoking (current, former, never), alcohol (zero, more than zero but less than one, one or more drinks per day), total physical activity (quartiles), total sitting time (quartiles), and BMI (<18.5, 18.5-<25.0, 25.0-<30.0, 30.0-<35.0, 35.0-<40.0, ≥40.0, kg/m2),19–22 as well as diseases that can be caused by sleep deficiency, including diabetes (yes, no), hypertension (yes, no), hypercholesterolemia (yes, no) and depression (yes, no).23–26 Statistical significance was determined using p<0.05.

Results

Study characteristics according to categories of weekday sleep duration in white and black participants are presented in Table 1. Among white participants, when compared to those reporting 7–8 hours of sleep, both those reporting < 6 hours or ≥9 hours of sleep duration were more likely to be female, unemployed and current smokers, and have a history of diabetes, hypertension, and depression, but they were less likely to be married, report a household income of 50k or more, have completed high school, or consume 1 or more drinks per day. In addition, < 6 hours of sleep was also associated with younger age and higher levels of total physical activity and energy intake, while ≥ 9 hours of sleep was associated with hypercholesterolemia. Among blacks, those reporting ≥ 9 hours of sleep were less likely to have completed high school, report a household income of 50k or more, but were more likely to be unemployed and current smokers and had a higher daily energy intake. Less than six hours of sleep in blacks was not associated with most characteristics, except for higher likelihood of reporting depression.

Table 1.

Baseline study characteristics of Blacks and Whites (age 40 – 79) in the Southern Community Cohort Study, 2002–2009

| Weekday sleep duration, hour | p-valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 | 6 | 7–8 | 9+ | ||

| Whites | |||||

| N | 2,180 | 3,933 | 8,100 | 1,341 | |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 50.9 (8.1) | 52.2 (8.5) | 53.5 (8.8) | 53.2 (9.1) | <.0001 |

| Female, % | 63.9 | 60.3 | 59.8 | 66.6 | <.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.5 (7.7) | 29.9 (7.4) | 29.2 (7.0) | 30.8 (8.0) | <.0001 |

| Less than high school, % | 27.6 | 21.7 | 17.4 | 24.5 | <.0001 |

| Married, % | 42.4 | 48.1 | 54.8 | 47.4 | <.0001 |

| Household income >50k, % | 8.7 | 19.0 | 26.1 | 13.7 | <.0001 |

| Unemployed, % | 62.8 | 49.5 | 48.8 | 71.4 | <.0001 |

| Current smoker, % | 47.0 | 38.4 | 31.3 | 36.5 | <.0001 |

| Total physical activity, MET hr/d, mean (SD) | 24.5 (21.2) | 24.9 (19.3) | 22.7 (17.3) | 19.9 (17.1) | <.0001 |

| Sitting, hr/d, mean (SD) | 9.0 (5.0) | 8.9 (4.5) | 8.7 (4.4) | 9.3 (4.6) | <.0001 |

| Alcohol consumption, 1+ drink/d , % | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 14.2 | <.0001 |

| Dietary intakes, mean (SD) | |||||

| total calories, kcal | 2403 (1323) | 2321 (1264) | 2221 (1158) | 2290 (1215) | <.0001 |

| total fat, gram/day/kcal | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.96 |

| total fiber, gram/day/kcal | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | <.0001 |

| History of chronic diseases | |||||

| Diabetes, % | 18.6 | 16.4 | 14.3 | 21.7 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension, % | 49.4 | 43.3 | 40.6 | 48.0 | <.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 35.3 | 34.6 | 35.9 | 42.4 | <.0001 |

| Depression, % | 49.5 | 38.1 | 33.8 | 54.8 | <.0001 |

| Blacks | |||||

| N | 6,314 | 9,916 | 18,657 | 4,934 | |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 50.2 (7.7) | 50.7 (8.0) | 51.1 (8.6) | 50.8 (8.7) | <.0001 |

| Female, % | 59.6 | 57.2 | 57.7 | 57.1 | <.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 31.0 (7.8) | 30.6 (7.5) | 30.3 (7.3) | 30.2 (7.9) | <.0001 |

| Less than high school, % | 29.5 | 24.9 | 30.2 | 36.8 | <.0001 |

| Married, % | 27.8 | 31.2 | 30.2 | 28.4 | <.0001 |

| Household income >50k, % | 5.7 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 2.9 | <.0001 |

| Unemployed, % | 55.0 | 49.2 | 54.9 | 67.3 | <.0001 |

| Current smoker, % | 41.5 | 41.4 | 42.0 | 47.3 | <.0001 |

| Total physical activity, MET hr/d, mean (SD) | 24.5 (20.4) | 25.0 (19.6) | 24.3 (19.6) | 22.4 (19.4) | <.0001 |

| Sitting, hr/d, mean (SD) | 9.5 (5.3) | 9.5 (5.1) | 9.2 (5.0) | 9.7 (5.4) | <.0001 |

| Alcohol consumption, 1+ drink/d , % | 24.5 | 23.8 | 24.1 | 26.9 | <.0001 |

| Dietary intakes, mean (SD) | |||||

| total calories, kcal | 2699 (1530) | 2633 (1481) | 2676 (1512) | 2825 (1581) | <.0001 |

| total fat, gram/kcal | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.10 |

| total fiber, gram/kcal | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | <.0001 |

| History of chronic diseases | |||||

| Diabetes, % | 20.4 | 18.8 | 19.8 | 21.0 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension, % | 55.8 | 54.9 | 53.2 | 53.5 | <.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 28.2 | 27.0 | 25.3 | 24.5 | <.0001 |

| Depression, % | 26.3 | 19.1 | 15.6 | 18.8 | <.0001 |

P-values were derived from Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: MET, metabolic equivalents; SD, standard deviation

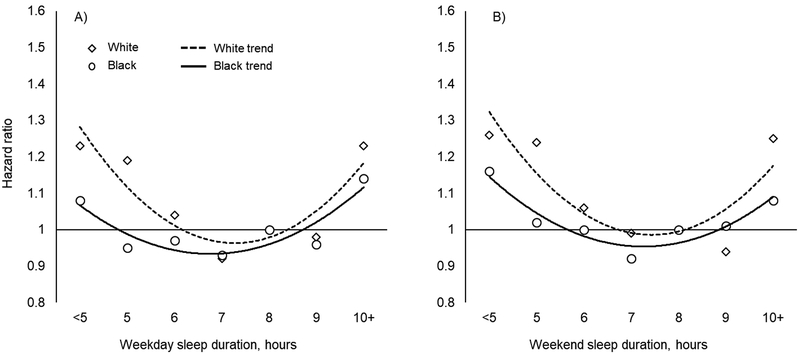

We first examined the race-specific relationship between sleep duration and all-cause mortality across the wide range of sleep hours, from <5 to ≥10 hours (Table 2 and Figure 1). U-shaped associations were observed among both races, however the patterns appeared to be more pronounced in whites than in blacks, and there was a statistically significant interaction between race and sleep duration in relation to all-cause mortality (p-for-interaction, 0.001 for weekday sleep duration and 0.01 for weekend sleep). Specifically, less than 5 hours of sleep was associated with ~25% increase in all-cause mortality in whites (HR <5 vs 8 hr (95% CI), weekday: 1.23 (1.04, 1.46); weekend: 1.26 (1.06, 1.51)), while the effects were weaker and less consistent in blacks (weekday: 1.08 (0.97, 1.20); weekend: 1.11 (1.00, 1.24)). Moreover, 5 hours of sleep was associated with increased all-cause mortality in whites (weekday: 1.19 (1.02, 1.38); weekend: 1.24 (1.06, 1.46)) but not in blacks (weekday: 0.95 (0.87, 1.04); weekend 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) for weekday and weekend sleep, respectively). Sleep duration of 10 hours or more was also associated with higher increase in all-cause mortality in whites (weekday: 1.23 (1.02, 1.48); weekend: 1.25 (1.08, 1.46)) than in blacks (weekday: 1.14 (1.04, 1.25); weekend: 1.08 (1.00, 1.16)). These findings with respect to all-cause mortality persisted after adjustment for multiple confounder (Model 2), although additional adjustment for potential mediators attenuated the findings considerably (Model 3).

Table 2.

Associations (HR (95% CI)) between sleep duration (seven categories) and all-cause mortality in blacks and whites (age 40 – 79) in the Southern Community Cohort Study

| Sleep duration, hour | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10+ | |

| Weekday | |||||||

| White | |||||||

| No. of Deaths | 177 | 226 | 579 | 437 | 646 | 100 | 137 |

| Model 1 | 1.64 (1.39, 1.94) | 1.30 (1.11, 1.51) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | 0.75 (0.66, 0.84) | ref | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24) | 1.57 (1.30, 1.88) |

| Model 2 | 1.23 (1.04, 1.46) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.38) | 1.04 (0.93, 1.16) | 0.92 (0.82, 1.04) | ref | 0.98 (0.79, 1.21) | 1.23 (1.02, 1.48) |

| Model 3 | 1.18 (0.99, 1.40) | 1.11 (0.96, 1.30) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.14) | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | ref | 0.93 (0.75, 1.15) | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) |

| Black | |||||||

| No. of Deaths | 403 | 576 | 1500 | 1007 | 2085 | 319 | 638 |

| Model 1 | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) | 0.90(0.82,0.99) | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) | 0.85 (0.79, 0.92) | ref | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) | 1.2 (1.13, 1.35) |

| Model 2 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.87, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.93 (0.86, 1.00) | ref | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.25) |

| Model 3 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.17) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 0.93 (0.86, 1.00) | ref | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.21) |

| Weekend | |||||||

| White | |||||||

| No. of Deaths | 155 | 201 | 483 | 401 | 685 | 142 | 235 |

| Model 1 | 1.91 (1.60, 2.27) | 1.64 (1.40, 1.91) | 1.29 (1.15, 1.45) | 0.95 (0.84, 1.07) | ref | 0.88 (0.73, 1.05) | 1.52 (1.31, 1.76) |

| Model 2 | 1.26 (1.06, 1.51) | 1.24 (1.06, 1.46) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.20) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.12) | ref | 0.94 (0.78, 1.12) | 1.25 (1.08, 1.46) |

| Model 3 | 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) | 1.17 (1.00, 1.37) | 1.03 (0.91, 1.15) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) | ref | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) | 1.17 (1.01, 1.36) |

| Black | |||||||

| No. of Deaths | 402 | 560 | 1294 | 898 | 1990 | 397 | 987 |

| Model 1 | 1.21 (1.09, 1.35) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.88 (0.82, 0.95) | ref | 0.99 (0.89, 1.10) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.21) |

| Model 2 | 1.11 (1.00, 1.24) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | ref | 1.01 (0.91, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.00, 1.16) |

| Model 3 | 1.36 (0.96, 1.19) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.92 (0.85, 1.00) | ref | 1.02 (0.91, 1.13) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) |

Model 1: adjusted for age (continuous) and sex (male, female).

Model 2: adjusted for variables in Model 1 and education (less than high school, high school, vocational training or some college, college or higher), household income (<$15,000, $15,000-<$25,000, $25,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000), marital status (Married, separated, divorced or widowed, never married), and employment status (yes, no). P-for-interaction between sleep duration categories and race: 0.001 for weekday sleep and 0.01 for weekend sleep.

Model 3: adjusted for variables in Model 2 and smoking (current, former, never), alcohol (zero, more than zero but less than one, one or more drinks per day), total physical activity (quartiles), total sitting time (quartiles), BMI (<18.5, 18.5-<25.0, 25.0-<30.0, 30.0-<35.0, 35.0-<40.0, ≥40.0, kg/m2), and history of diabetes (yes, no), hypertension (yes, no), hypercholesterolemia (yes, no) and depression (yes, no).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio

Figure 1.

Associations between weekday and weekend sleep duration (seven categories) and total mortality in blacks and whites (age 40 – 79) in the Southern Community Cohort Study. Diamonds (Blacks) and circles (Whites) represent hazard ratios for each category of sleep duration. Dotted (White) and solid (Black) lines represent polynomial trend lines. Models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (male, female), education (less than high school, high school, vocational training or some college, college or higher), household income (<$15,000, $15,000-<$25,000, $25,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000), marital status (Married, separated, divorced or widowed, never married), and employment status (yes, no)

Next we examined cause-specific mortality and for this analysis we combined more extreme sleep duration categories to conserve statistical power (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 1 for weekday sleep and Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 2 for weekday sleep). In whites, we found stronger associations with both < 6 hours and ≥ 9 hours of sleep for cardiovascular disease than all-cause mortality, and the elevated mortality risk was particularly high for <6 hourrs of sleep on weekends (1.59 (1.26, 2.01)). In contrast, we found no association between sleep duration and cardiovascular mortality in blacks. Also little if any association between sleep duration and cancer mortality was found in either whites or blacks. Excluding deaths that occurred within two years (251 deaths in whites and 618 deaths in blacks) after the baseline had little impact on our findings (data not shown).

Table 3.

Associations (HR (95% CI)) between weekday sleep duration and mortality in blacks and whites (age 40 – 79) in the Southern Community Cohort Study, by race

| Weekday sleep duration, hour | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 | 6 | 7–8 | 9+ | |

| White | ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 403 | 579 | 1083 | 237 |

| Model 1 | 1.62 (1.44, 1.82) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) | ref | 1.44 (1.25, 1.65) |

| Model 2 | 1.24 (1.11, 1.40) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.19) | ref | 1.14 (0.99, 1.32) |

| Model 3 | 1.17 (1.04, 1.32) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) | ref | 1.08 (0.94, 1.25) |

| CVD mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 114 | 153 | 276 | 65 |

| Model 1 | 1.88 (1.51,2.34) | 1.24 (1.01, 1.51) | ref | 1.56 (1.19,2.05) |

| Model 2 | 1.45 (1.16, 1.81) | 1.14 (0.93, 1.39) | ref | 1.25 (0.95, 1.64) |

| Model 3 | 1.32 (1.06, 1.65) | 1.11(0.91, 1.36) | ref | 1.15 (0.88, 1.52) |

| Cancer mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 86 | 118 | 276 | 49 |

| Model 1 | 1.44 (1.13, 1.83) | 0.96 (0.77, 1.19) | ref | 1.17 (0.86, 1.59) |

| Model 2 | 1.17 (0.92, 1.50) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.11) | ref | 1.02 (0.75, 1.38) |

| Model 3 | 1.14 (0.89, 1.47) | 0.88 (0.71, 1.10) | ref | 0.99 (0.73, 1.35) |

| Black | ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 979 | 1500 | 3092 | 957 |

| Model 1 | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) | ref | 1.20 (1.12.1.29) |

| Model 2 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | ref | 1.10 (1.02, 1.18) |

| Model 3 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.05) | ref | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) |

| CVD mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 312 | 491 | 944 | 276 |

| Model 1 | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.14) | ref | 1.14 (0.99, 1.30) |

| Model 2 | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.18) | ref | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) |

| Model 3 | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.18) | ref | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) |

| Cancer mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 241 | 421 | 829 | 238 |

| Model 1 | 0.96 (0.83, 1.10) | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | ref | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) |

| Model 2 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.10) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | ref | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) |

| Model 3 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | ref | 1.01 (0.87, 1.17) |

Model 1: adjusted for age (continuous) and sex (male, female).

Model 2: adjusted for variables in Model 1 and education (less than high school, high school, vocational training or some college, college or higher), household income (<$15,000, $15,000-<$25,000, $25,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000), marital status (Married, separated, divorced or widowed, never married), and employment status (yes, no). P-for-interaction between sleep duration categories and race: 0.002 for all-cause mortality, 0.18 for CVD mortality and 0.20 for cancer mortality.

Model 3: adjusted for variables in Model 2 and smoking (current, former, never), alcohol (zero, more than zero but less than one, one or more drinks per day), total physical activity (quartiles), total sitting time (quartiles), BMI (<18.5, 18.5-<25.0, 25.0-<30.0, 30.0-<35.0, 35.0-<40.0, ≥40.0, kg/m2), and history of diabetes (yes, no), hypertension (yes, no), hypercholesterolemia (yes, no) and depression (yes, no).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio

Table 4.

Associations (HR (95% CI)) between weekend sleep duration and mortality in blacks and whites (age 40 – 79) in the Southern Community Cohort Study, by race

| Weekend sleep duration, hour | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 | 6 | 7–8 | 9+ | |

| white | ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 356 | 483 | 1086 | 377 |

| Model 1 | 1.78 (1.57,2.00) | 1.32 (1.18, 1.47) | ref | 1.21 (1.08, 1.36) |

| Model 2 | 1.25 (1.11, 1.42) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) | ref | 1.12 (0.99, 1.26) |

| Model 3 | 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) | ref | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) |

| CVD mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 104 | 134 | 262 | 108 |

| Model 1 | 2.25 (1.79,2.83) | 1.54 (1.25, 1.89) | ref | 1.48 (1.19, 1.86) |

| Model 2 | 1.59 (1.26,2.01) | 1.25 (1.02, 1.54) | ref | 1.37 (1.10, 1.72) |

| Model 3 | 1.47 (1.16, 1.85) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.48) | ref | 1.28 (1.02, 1.61) |

| Cancer mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 76 | 90 | 283 | 80 |

| Model 1 | 1.54 (1.20, 1.99) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.22) | ref | 1.02 (0.79, 1.30) |

| Model 2 | 1.19 (0.92, 1.54) | 0.82 (0.64, 1.04) | ref | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) |

| Model 3 | 1.12 (0.86, 1.46) | 0.80 (0.63, 1.02) | ref | 0.92 (0.72, 1.19) |

| Black | ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 962 | 1294 | 2888 | 1384 |

| Model 1 | 1.16 (1.08, 1.25) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | ref | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20) |

| Model 2 | 1.09 (1.01, 1.17) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | ref | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) |

| Model 3 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | ref | 1.06 (0.99, 1.13) |

| CVD mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 296 | 426 | 903 | 398 |

| Model 1 | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) | ref | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) |

| Model 2 | 1.08 (0.95, 1.24) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.21) | ref | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) |

| Model 3 | 1.06 (0.93, 1.21) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.19) | ref | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) |

| Cancer mortality | ||||

| No. of death (%) | 241 | 346 | 794 | 348 |

| Model 1 | 1.07 (0.93, 1.24) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) | ref | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) |

| Model 2 | 1.02 (0.88, 1.18) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | ref | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) |

| Model 3 | 0.99 (0.86, 1.15) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | ref | 0.98 (0.87, 1.12) |

Model 1: adjusted for age (continuous) and sex (male, female).

Model 2: adjusted for variables in Model 1 and education (less than high school, high school, vocational training or some college, college or higher), household income (<$15,000, $15,000-<$25,000, $25,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000), marital status (Married, separated, divorced or widowed, never married), and employment status (yes, no). P-for-interaction between sleep duration categories and race: 0.04 for all-cause mortality, 0.03 for CVD mortality, and 0.19 for cancer mortality.

Model 3: adjusted for variables in Model 2 and smoking (current, former, never), alcohol (zero, more than zero but less than one, one or more drinks per day), total physical activity (quartiles), total sitting time (quartiles), BMI (<18.5, 18.5-<25.0, 25.0-<30.0, 30.0-<35.0, 35.0-<40.0, ≥40.0, kg/m2), and history of diabetes (yes, no), hypertension (yes, no), hypercholesterolemia (yes, no) and depression (yes, no).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio

Discussion

In this cohort of racially-diverse and predominantly low-income populations, we confirmed the previously reported U-shaped associations between sleep duration and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in white participants. In blacks, the relationship between sleep duration and mortality was generally weaker and elevated mortality was only observed for extreme sleep durations (<5 and 10+ hours).

Our finding of a U-shaped association between sleep duration and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in white participants is largely consistent with previous studies in US cohorts with predominantly white populations, such as the Nurse Health Study,27 the Cancer Prevention Study II,28 and the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.29 However, less is known about the relationship between sleep duration and mortality in the black population. To the best of our knowledge, only the Multiethnic Cohort (MEC) has specifically examined differences in the sleep-mortality association between blacks and whites.17 Although their population was from different geographic regions (Hawaii and Los Angeles) and on average had higher socioeconomic status when compared to subjects in the SCCS, their findings were largely comparable to ours. For example, they found ≤5 hours of sleep was associated with an increase in all-cause mortality in whites (HR (95% CI), 1.30 (1.14, 1.48)) but not in blacks (1.06 (0.96, 1.17)). On the other hand, the MEC study found that ≥9 hours of sleep was associated with all-cause mortality in both whites (1.26 (1.14, 1.38)) and blacks (1.17 (1.06, 1.30)), although the magnitude of effects were lower in blacks than in whites. Overall, both our finding and those in the MEC suggest that the sleep duration was a weaker predictor of all-cause mortality in blacks when compared to whites.

Our study extends the result of the MEC study by examining cause-specific mortality in relation to sleep duration. In particular, we found that although the effects of short sleep on mortality seem to be more pronounced for cardiovascular mortality in whites, which was consistent with previous studies,16 the null findings for short sleep and mortality in blacks remained when we examined cardiovascular deaths. It is unclear what factors may explain the different effects of short sleep on cardiovascular mortality in blacks and whites, but there is emerging evidence suggesting that race may modulate the relationship between sleep and multiple cardiometabolic outcomes and risk markers. For example, in MEC, short sleep (≤ 6 hour) was associated with modestly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes with marginal statistical significance in whites (1.08 (0.96, 1.20)), but no evidence of association was found in blacks (0.98 (0.87, 1.11)).30 Moreover, in a cross-sectional analysis of the 2005 National Health Interview Survey, although short sleep was associated with higher odds of having diabetes in both whites and blacks, the odds ratio for blacks (1.66) appeared to be lower than that for whites (1.87), and the study detected a statistically significant interaction between sleep duration and race in relation to diabetes.31 In addition, a smaller study of 248 African Americans also found that sleep was not associated with metabolic syndrome or individual cardiometabolic markers including fasting glucose, triglycerides, and cholesterol,32 despite a well-established relationship between sleep and metabolic disorders in white populations.33 Finally, in a group of adolescents, actigraph-measured sleep was inversely associated with blood pressure in whites, but not in blacks.34 Taken together, these findings appeared to be consistent with our results and suggest that relationships between short sleep and cardiometabolic health are weaker in the black population. However, our understanding in this area remains limited, and many of the aforementioned studies are small and cross-sectional in nature. Additional data from prospective studies with sufficiently large samples of black Americans are needed to firmly establish race-specific relationships between sleep and cardiometabolic health outcomes.

It is worth noting that both our study and the MEC study found that long sleep was a significant predictor of higher all-cause mortality in blacks. Some previous studies found that blacks are more likely to report long sleep than whites in the US. For example, an analysis of the nationally representative sample found that blacks are 72% more likely to report long sleep duration (≥9 hr) than whites.12 Another cross-sectional analysis of the American Time Use Survey also found that when compared to whites, blacks were 87% more likely to report extremely long sleep (≥11 hr).9 In the SCCS, we also observed a higher prevalence of long sleep in blacks (12.4%) than in whites (8.6%). Given the higher prevalence of longer sleep in blacks, and the significant association between long sleep and higher mortality, further research is needed to identify environmental and individual factors that may cause longer sleep in this population to inform the development of potential intervention strategies to change sleep behavior and improve health.

Our study has several strengths. First, it is conducted in a uniquely diverse cohort with a large number of blacks and relatively long follow-up, which allowed for adequate power to examine the relationship between sleep duration and all-cause as well as cause-specific mortality in an understudied population. Also, the large sample size has allowed us to perform sensitivity analyses in which deaths diagnosed within two years after sleep assessment were excluded, which should have reduced the likelihood of reverse causation. Our study also has several limitations. Most importantly, sleep durations were self-reported and may be prone to error. Previous studies which compared objectively-measured and self-reported sleep durations found a moderate overall correlation between the two (r=0.45–0.47), and on average, self-report overestimated sleep duration by ~1 hr.23,35 These studies also suggested that the reliability of self-reported sleep was lower in blacks than in whites, although the amount of overestimation tended to be larger in whites. Racial differences in self-report patterns could lead to bias in estimating racial difference in sleep-health relationships. Therefore, it is important for future studies to use objectively measured sleep duration to examine and compare the relationship between sleep duration and mortality in different racial and ethnic groups. In addition, sleep is a complex behavior that cannot be characterized by duration alone. Unfortunately, we did not have information on other sleep characteristics, such as sleep quality, sleep timing and sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, all of which are important determinants of health independent of sleep duration. We encourage future studies to comprehensively examine different aspects of sleep in relation to health in the black population.

In summary, our study identified potential differences in the shape of the sleep-mortality associations between blacks and whites, with weaker associations in blacks. Future studies utilizing valid and comprehensive measures of sleep may be particularly valuable to evaluate the health risks associated with unhealthy sleep in the black population and assess reasons for potentially different health effects of sleep in blacks compared with whites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The SCCS was supported by NIH grants R01CA92447 and U01CA202979. The work was also supported by Intramural Research Fund from National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rangaraj VR, Knutson KL. Association between sleep deficiency and cardiometabolic disease: implications for health disparities. Sleep Med. 2016;18:19–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo JC, Groeger JA, Cheng GH, Dijk DJ, Chee MW. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive performance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2016;17:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Yin JY, Yang WS, et al. Sleep duration and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(12):7509–7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jike M, Itani O, Watanabe N, Buysse DJ, Kaneita Y. Long sleep duration and health outcomes: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hale L, Do DP. Racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1096–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169(9):1052–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunes J, Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, et al. Sleep duration among black and white Americans: results of the National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(3):317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basner M, Spaeth AM, Dinges DF. Sociodemographic characteristics and waking activities and their role in the timing and duration of sleep. Sleep. 2014;37(12):1889–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whinnery J, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, Grandner MA. Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep. 2014;37(3):601–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson CL, Redline S, Emmons KM. Sleep as a potential fundamental contributor to disparities in cardiovascular health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:417–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laposky AD, Van Cauter E, Diez-Roux AV. Reducing health disparities: the role of sleep deficiency and sleep disorders. Sleep Med. 2016;18:3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arias E, Xu J. United States life tables, 2015. 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper S, Rushani D, Kaufman JS. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap, 2003–2008. JAMA. 2012;307(21):2257–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu TZ, Xu C, Rota M, et al. Sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality: A flexible, non-linear, meta-regression of 40 prospective cohort studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;32:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin J, Jin X, Shan Z, et al. Relationship of Sleep Duration With All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, Wilkens LR, Schembre SM, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN, Goodman MT. Insufficient and excessive amounts of sleep increase the risk of premature death from cardiovascular and other diseases: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):377–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Steinwandel MD, et al. Southern community cohort study: establishing a cohort to investigate health disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7):972–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson M, Munafo MR, Taylor AE, Treur JL. Evidence for genetic correlations and bidirectional, causal effects between smoking and sleep behaviours. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brower KJ. Insomnia, alcoholism and relapse. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(6):523–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kline CE. The bidirectional relationship between exercise and sleep: Implications for exercise adherence and sleep improvement. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;8(6):375–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucassen EA, Rother KI, Cizza G. Interacting epidemics? Sleep curtailment, insulin resistance, and obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1264:110–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):838–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Mei H, Jiang YR, et al. Relationship between Duration of Sleep and Hypertension in Adults: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(9):1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhai L, Zhang H, Zhang D. Sleep Duration and Depression among Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(9):664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabanayagam C, Shankar A. Sleep duration and hypercholesterolaemia: Results from the National Health Interview Survey 2008. Sleep Med. 2012;13(2):145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel SR, Ayas NT, Malhotra MR, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004;27(3):440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(2):131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Q, Keadle SK, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. Sleep duration and total and cause-specific mortality in a large US cohort: interrelationships with physical activity, sedentary behavior, and body mass index. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;180(10):997–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maskarinec G, Jacobs S, Amshoff Y, et al. Sleep duration and incidence of type 2 diabetes: the Multiethnic Cohort. Sleep Health. 2018;4(1):27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zizi F, Pandey A, Murrray-Bachmann R, et al. Race/ethnicity, sleep duration, and diabetes mellitus: analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kazman JB, Abraham PA, Zeno SA, Poth M, Deuster PA. Self-reported sleep impairment and the metabolic syndrome among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(4):410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iftikhar IH, Donley MA, Mindel J, Pleister A, Soriano S, Magalang UJ. Sleep Duration and Metabolic Syndrome. An Updated Dose-Risk Metaanalysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(9):1364–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mezick EJ, Hall M, Matthews KA. Sleep duration and ambulatory blood pressure in black and white adolescents. Hypertension. 2012;59(3):747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson CL, Patel SR, Jackson WB, 2nd, Lutsey PL, Redline S. Agreement between self-reported and objectively measured sleep duration among white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese adults in the United States: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Sleep. 2018;41(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.