Abstract

Objectives

Sleep complaints, such as insomnia and sleep disturbances caused by PTSD, are more common among women veterans than non-veteran women. Alcohol use among some women may be partially motivated by the desire to improve sleep. This study evaluated rates of alcohol use as a sleep aid among women veterans, and explored the relationship between alcohol use to aid sleep and drinking frequency and sleeping pill use.

Design and Setting

National cross-sectional population-based residential mail survey on sleep and other symptoms.

Participants

Random sample of women veteran VA users who completed a postal survey (N=1,533)

Interventions

None.

Measurements

The survey included demographics, Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Primary Care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD), and items on alcohol use frequency (days/week), use of prescription or over-the-counter sleep medications, and use of alcohol as a sleep aid (yes/no for each item) over the past month.

Results

14.3% of respondents endorsed using alcohol to aid sleep. Logistic regression models showed more severe insomnia (OR=1.03; 95%CI:1.01–1.06) and PTSD (OR=2.11; 95%CI:1.49–2.97) were associated with increased odds of using alcohol to aid sleep. Alcohol use to aid sleep was associated with increased odds of daily drinking (OR=8.43; 95%CI:3.91–20.25) and prescription (OR=1.79; 95%CI:1.34–2.38) and over-the-counter sleep aid use (OR=1.54; 95%CI:1.12–2.11).

Conclusions

Insomnia and PTSD may increase risk for using alcohol as a sleep aid, which may increase risk for unhealthy drinking and for mixing alcohol with sleep medications. Findings highlight the need for alcohol use screening in the context of insomnia and for delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia to women veterans with insomnia.

Keywords: alcohol, insomnia, sleep medications, women, PTSD, Veterans

INTRODUCTION

Women veterans are a growing segment of the Veteran population, currently numbering approximately 2 million, many of whom receive care with the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.1 Sleep complaints are common among women veterans, and a recent regional survey estimated that 52% of women VA users meet the basic criteria for insomnia disorder (poor sleep with daytime consequences).2

Alcohol use has been linked with sleep problems,3 including insomnia, and among women, alcohol use is associated with numerous mental and physical health consequences and with increased mortality.4 Estimates of alcohol use among women veterans are similar to those among women civilians, indicating that between 19–32% are engaging in alcohol misuse (i.e., drinking above recommended limits).5,6 However, there is evidence that women veterans under-disclose alcohol use to medical providers.7,8 Women veterans with insomnia who use alcohol may be partially motivated to drink in order to initiate sleep. Although sex-specific rates are not available, using alcohol as a “sleep aid” may be common among individuals with insomnia.9 Identifying the extent to which women veterans may be using alcohol specifically to aid sleep may inform avenues to intervene with sleep problems, prevent deleterious effects of alcohol use, and identify a group of women veterans who may be at risk for continued sleep problems and alcohol problems.

The self-medication hypothesis proposes that substance use may be a direct attempt to cope with negative affect,10,11 as in the context of sleep disturbance or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).12,13 PTSD is the most common diagnosis for returning Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom service members 14 and is a common but often untreated correlate of both insomnia and alcohol use.15 A high proportion of women veterans report experiencing rape and sexual harassment during military service,16,17 which puts them at risk for developing PTSD. Prior research has demonstrated women with PTSD experience more sleep disturbance than women without PTSD,18 and half of women veterans with insomnia also have PTSD.19 A recent review highlighted the need to consider sleep in the context of PTSD, given the potential for sleep disruption to impede PTSD recovery and contribute to functional impairment.20 Given that poor sleep may contribute to worse psychiatric symptomology,21 women veterans with PTSD who also endorse insomnia symptoms may be at increased risk for alcohol misuse and the development of alcohol use disorders.

While alcohol may initially produce sedating effects, potentially reducing the amount of time it takes to fall asleep, it may also interfere with an individual’s ability to maintain sleep over the course of the night and lead to increased middle of the night awakenings.22,23 However, the initial sedating effects of alcohol diminish after a few days, as tolerance is rapidly established, while the disrupting effects of alcohol use on sleep persist.24 Given that alcohol may lose its effectiveness as a sleep aid over time and contribute to further sleep problems, women who use alcohol to aid sleep may be at risk for complications from combining alcohol with prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) sleep medications, some of which should not be taken in combination with alcohol.25 An international systematic review of alcohol and sedative-hypnotic co-use estimated that up to 79% of women aged 40 and older who use sedative-hypnotics also use alcohol, and up to 28% of adult sedative-hypnotic users may be mixing alcohol with their sleep medications. Identifying the extent to which women veterans who use alcohol as a sleep aid are also using sleep medications may inform efforts to prevent health consequences from mixing medications with alcohol and highlight an opportunity for education and intervention.

Current Study

Using data from a national survey of women veterans who receive VA health care, we examined the relationship between symptoms of insomnia, symptoms of PTSD, use of alcohol specifically to aid sleep and concomitant use of sleeping pills. Our primary hypothesis was that insomnia severity would be uniquely predictive of having used alcohol to aid sleep, even after accounting for demographics and PTSD symptoms. Our second hypothesis was that, among women veterans who used alcohol, those who used alcohol specifically to aid sleep would be more likely to have used alcohol daily than those who did not. Finally, our third hypothesis was that women veterans who used alcohol to aid sleep would be more likely to have used prescription and/or OTC sleep medications than women who did not use alcohol to aid sleep.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

The study sample was drawn from the population of >300,000 women veterans across the nation who received care at a VA facility in the six-month period prior to initiation of survey mailing (May 29 to November 28, 2012), with the goal of receiving 1,500 completed surveys to make reliable estimates of rates of sleep disorders. To achieve this sample, surveys were sent to a random sample of 4,000 women veterans, in batches of 1,000 surveys, between 2/2013 and 10/2013. If no response was received within three weeks, a second copy of the survey was sent. After the final round of mailed surveys were sent, to reduce the risk of non-response bias, non-responders from the first 1,000-person mailing were contacted by phone and provided with the opportunity to complete the survey verbally. Using these methods, a total of 1,559 surveys were returned by mail or completed by telephone (total response rate = 39%). Using available administrative data (demographics and military service-related variables) about non-responders, there were minimal differences between responders and non-responders in the sample. Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board and a waiver of documentation of informed consent was obtained.

Measures

The items used in the current study were drawn from a study conducted for the purpose of estimating the prevalence of insomnia and other sleep disorders, and identifying insomnia treatment preferences among women veterans.26 The survey included cover material describing the survey as research and four pages of questionnaire items. The specific items used in the current analyses are described below.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic variables collected and included in the current analyses were age, categories of race/ethnicity (respondents were asked to check all categories that applied), and employment status (employed for wages yes/no). For race/ethnicity, yes/no variables representing the three most commonly endorsed groups were included in statistical models (White/Caucasian, Hispanic/Latina, African American or Black).

Alcohol use

Respondents were asked whether they had used alcohol to aid sleep in the past month (yes/no), and the number of days they drank alcohol in the past week (0–7). Alcohol to aid sleep was the primary outcome for analyses of our primary hypothesis and focal predictor for our analyses for hypotheses two and three. Number of days of alcohol use was used to identify participants who consumed alcohol in the past week (on one or more days), and was then dichotomized into those who drank 1–6 out of seven days in the previous week versus seven out of seven days in the previous week. This cutoff was used to identify whether respondents reported drinking at or above the upper limit of moderate drinking as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; i.e., up to one alcoholic drink per day for women) recommended drinking guidelines,27 and compare to those who may be at lower risk for alcohol use problems. This variable was used in analyses for hypothesis two.

Insomnia severity

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI),28 a self-report instrument with seven items scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much), assessed perceived severity of insomnia symptoms in the past two weeks. Items are summed and higher scores indicate more severe insomnia (Range: 0–28). Continuous ISI score was used as a predictor in analyses of hypothesis one.

PTSD symptoms

The PC-PTSD29 is a 4-item PTSD screener developed for use in medical settings to assess presence of past-month PTSD symptom clusters. Individuals are asked “In your life, have you ever had any experience that was so frightening, horrible, or upsetting that, in the past month, [they]” have had symptoms related to re-experiencing (nightmares), avoidance, hyperarousal (on guard, watchful, or easily startled), or numbing (all yes/no, one point each). The PC-PTSD is considered positive if the total score is three or four. PC-PTSD screen status was used as a predictor in analyses for hypothesis one.

Pharmacologic sleep aid use

Women were also asked whether they had used 1) prescribed sleep medications and 2) OTC sleep medications in the past month (both yes/no). Items were included in analyses for hypothesis three.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (i.e., means, standard deviations, percentages) were calculated for each variable and bivariate analyses were conducted between alcohol use as a sleep aid and all predictors and covariates. For hypothesis one (that insomnia severity would be predictive of using alcohol to aid sleep), the outcome variable was use of alcohol to aid sleep during the previous month (binary; yes/no). To test hypothesis one, a logistic regression models was fit where the outcome was predicted as a function of demographic characteristics, ISI score, and PC-PTSD screen status. For the second and third hypotheses, the use of alcohol to aid sleep (yes/no) was the focal predictor in logistic regression models, but the outcomes differed for the two hypotheses. For the test of hypothesis two, only data from those who had consumed any alcohol in the past week were included. The outcome for hypothesis two was daily use of alcohol (yes/no). Due to the small percentage of those using alcohol seven days per week (the outcome for hypothesis two), multivariable logistic regression was used for the test of hypothesis two. The outcomes for hypothesis three were: 1) past-month use of prescription sleeping medications, 2) past-month use of OTC sleeping medications (both yes/no), 3) past-month use of prescription and/or OTC sleeping medications. Predictive margins (also known as recycled predictions) were computed using the “margins” command for hypothesis three. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 13.

RESULTS

A total of 1,538 women veterans (98% of all returned surveys) completed the survey with sufficient data (i.e., provided information on all variables of interest) to be included in the current analyses. To compare responders to non-responders, we fit a logistic regression model predicting non-response as a function of the following variables: race, combat exposure, presence of military sexual trauma, having a business phone, home phone, mobile phone, age (in decades), days since last VA health visit, period of service, income, service connected injury, and region of country. Three factors were significantly related to non-response, including race/ethnicity, days since last VA healthcare visit and age. Responders were less likely to be Hispanic/Latina (OR = 0.7; p=.039), more likely to be white (OR=1.4, p=.003), and more likely to have had a recent VA visit (OR =.006, p<.001). Response rate varied by age, in decades (Wald chi-square (7)=75.4, p<.001), where the likelihood of response increased with age until reaching a maximum for those in their 70s, and then declined thereafter.

Overall, 14.3% of the sample reported using alcohol to aid sleep in the past month. Sample characteristics and bivariate relationships between use of alcohol to aid sleep and predictors are presented in Table 1. In unadjusted analyses (Table 1), younger age, identifying as African-American or Black, being employed, positive PC-PTSD screen and higher ISI score were all positively associated with having used alcohol to aid sleep. Identifying as White was negatively associated with having used alcohol to aid sleep. Those who used alcohol to aid sleep were also more likely to drink daily and to have used sleeping medications (prescription or OTC) in the past month. In the multivariable logistic regression model predicting alcohol to aid sleep (Table 2), being aged 65 and older (compared to 18–34), being employed for wages, having a higher ISI score, and a positive PC-PTSD screen were all associated with increased odds of using alcohol to aid sleep in the past month.

Table 1 –

Characteristics of women Veterans by endorsement of using alcohol to aid sleep and bivariate differences between women who used and did not use alcohol to aid sleep in the past month.

| Full Sample (N=1533) | Use of Alcohol to Aid Sleep | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES (N=219) | NO (N=1,314) | ||||||

| Survey items | N | % | N | % | N | % | p-valuec |

| Age (years) | <.001 | ||||||

| 18–34 | 241 | 15.7 | 43 | 19.6 | 198 | 15.1 | |

| 35–44 | 244 | 15.9 | 49 | 22.4 | 195 | 14.8 | |

| 45–54 | 409 | 26.7 | 71 | 32.4 | 338 | 25.7 | |

| 55–64 | 404 | 26.4 | 48 | 21.9 | 356 | 27.1 | |

| 65 or older | 235 | 15.3 | 8 | 3.7 | 227 | 17.3 | |

| African-American/Blacka | 402 | 26.2 | 74 | 33.8 | 328 | 25.0 | .008 |

| Hispanic/Latinaa | 95 | 6.2 | 13 | 5.9 | 82 | 6.2 | 1.0 |

| White/Caucasiana | 1,005 | 65.6 | 128 | 58.5 | 877 | 66.7 | 0.021 |

| Other race/ethnicitya,b | 114 | 7.44 | 19 | 8.7 | 95 | 7.2 | 0.450 |

| No information on race/ethnicity | 20 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.9 | 18 | 1.4 | 0.581 |

| Employed for wages | 625 | 40.8 | 108 | 49.5 | 517 | 39.7 | .007 |

| ISI score (M ± SD) | 12.8±7.1 | 15.5±5.9 | 12.3±7.2 | <.001 | |||

| Clinical Insomnia (ISI score >=15) | 642 | 41.9 | 120 | 54.8 | 522 | 39.8 | <.001 |

| Positive PC-PTSD | 485 | 31.9 | 115 | 53.0 | 370 | 28.5 | <.001 |

| Days of use in the past week | <.001 | ||||||

| 0 days | 1027 | 67.6 | 23 | 10.5 | 1004 | 77.2 | |

| 1 day | 170 | 11.1 | 35 | 15.5 | 138 | 10.6 | |

| 2 days | 121 | 8.0 | 39 | 17.8 | 82 | 6.3 | |

| 3 days | 71 | 4.7 | 39 | 17.8 | 32 | 2.5 | |

| 4 days | 35 | 2.3 | 17 | 7.8 | 18 | 1.4 | |

| 5 days | 32 | 2.2 | 18 | 8.2 | 14 | 1.1 | |

| 6 days | 12 | 0.8 | 8 | 3.7 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| 7 days (daily drinking) | 50 | 3.4 | 41 | 18.7 | 9 | 0.7 | |

| Past-month use of any sleep medication (Rx or OTC) | 777 | 50.1 | 141 | 64.4 | 636 | 48.4 | <.001 |

| Past-month Rx sleep medication use | 584 | 38.1 | 110 | 50.2 | 474 | 36.1 | <.001 |

| Past-month OTC sleep medication use | 360 | 23.5 | 67 | 30.6 | 293 | 22.3 | .007 |

ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; Med = medication; OTC = Over the counter; Rx = Prescription; PC-PTSD = Primary Care-Posttraumatic Stress Disorder screen. P-values were derived from chi-square and analyses of covariance, where appropriate

Respondents were instructed to select all racial/ethnic groups that applied. Results presented are from each group compared to all others (e.g., those who identified as African-American/Black compared to those who did not identify as African-American/Black).

Includes Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Asian, and American Indian/Alaska Native, and Other.

p-value for bivariate differences between women who did (N=219) and did not (N=1,314) use alcohol to aid sleep.

Table 2:

Predictors of alcohol use to aid sleep via multivariable logistic regression model.

| Survey items | OR | CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–34 | Ref. group | ||

| 35–44 | 1.05 | 0.66–1.68 | .850 |

| 45–54 | 0.86 | 0.56–1.33 | .503 |

| 55–64 | 0.69 | 0.43–1.10 | .116 |

| 65 or older | 0.26 | 0.12–0.59 | .001 |

| African-American/Blacka | 1.09 | 0.61–1.96 | 0.766 |

| Hispanic/Latinaa | 0.75 | 0.37–1.53 | 0.424 |

| White/Caucasiana | 0.91 | 0.52–1.60 | 0.737 |

| Employed for wages | 1.41 | 1.03–1.94 | 0.034 |

| ISI score (M ± SD) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.015 |

| Positive PC-PTSD | 2.11 | 1.49–2.97 | 0.000 |

CI=Confidence Interval; ISI=Insomnia Severity Index; OR=Odds Ratio; PC-PTSD=Primary Care-Posttraumatic Stress Disorder screen.

Respondents were instructed to select all racial/ethnic groups that applied. Results presented are presented for those who did and did not select each of the three most commonly-endorsed categories (e.g., those who identified as African-American/Black compared to those who did not).

For hypothesis two (among those who consumed alcohol, those who used alcohol to aid sleep would be more likely to report daily alcohol use), endorsement of drinking to aid sleep was associated with increased odds of having consumed alcohol daily (OR=8.46; 95%CI: 4.00–17.87, p<.001). The predicted probabilities of having used alcohol daily were 21% (95%CI: 0.15–0.27) for those who endorsed using alcohol to aid sleep and 3% (95%CI: 0.01–0.50) for those who did not use alcohol to aid sleep.

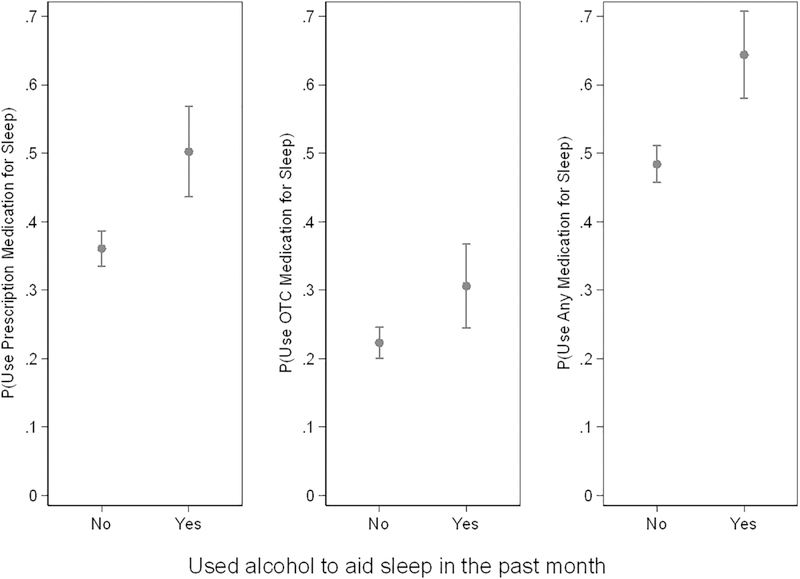

For hypothesis three (those who used alcohol to aid sleep would be more likely to have used prescription or OTC sleeping medications), using alcohol to aid sleep was associated with increased odds of using prescription sleep aids in the past month (OR=1.79; 95%CI: 1.34–2.38, p<.001). The predicted margins (probabilities) of having used prescription medications for sleep in the past month were 50% (95%CI: 0.44–0.57) for those who used alcohol to aid sleep and 36% (95%CI: 0.33–0.39) for those who did not use alcohol to aid sleep. Using alcohol to aid sleep was also associated with increased odds of using OTC sleep medications in the past month (OR=1.54; 95%CI: 1.12–2.11). The predicted probabilities of having used OTC sleep medications in the past month were 31% (95%CI: 0.20–0.37) for those who endorsed using alcohol to aid sleep and 22% (95%CI: 0.20–0.25) for those who did not use alcohol to aid sleep (Figure 1). For any sleeping medication use (either prescription medication or OTC medication or both), using alcohol to aid sleep was associated with increased odds of use in the past month (OR=1.93; 95%CI: 1.43–2.59). The predicted probabilities of having used any sleeping medication in the past month were 64% (95%CI:0.58–0.71) for those who endorsed using alcohol to aid sleep and 48% (95%CI: 0.46–0.51) for those who did not use alcohol to aid sleep (Figure 1).

Figure 1 –

Predicted probabilities of past month sleeping medication use by use of alcohol to aid sleep.

OTC = Over the counter. Predicted probabilities (predictive margins) for use of prescription sleep aids (left) and OTC sleep aids (right) among women Veterans by endorsement of using alcohol as a sleep aid.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe alcohol use as a sleep aid among women veterans and to investigate the relationships among alcohol use specifically to aid sleep, insomnia symptoms, sleeping pill use and PTSD symptoms. Overall, one in seven women reported having used alcohol to aid sleep in the past month. We found that both greater insomnia severity and screening positive for PTSD were associated with using alcohol to aid sleep. Using alcohol to aid sleep in the past month, in turn, was associated with daily drinking in the past week and with using prescription and OTC sleep aids within the past month.

In our sample, the proportion of women using alcohol to aid sleep (14%) was higher than the most recently available general US population data (11%; sex specific estimates were not available);30 although rates of past month alcohol use and rates of PTSD were similar to previous studies among women VA users.5,31,32 In our sample, almost one-third of women screened positive for PTSD. Insomnia and PTSD in women veterans are highly comorbid (sleep disturbance in 70–90% of those with PTSD; PTSD in 55% of those with insomnia),19,13 and our findings suggest they are associated with engagement in risky “self-medication” behaviors. Prior research found that sleep difficulties, but not PTSD symptoms, were associated with drinking to cope with negative affect, which may indicate that women with PTSD use alcohol specifically to relieve negative affect related to sleep disturbance and nightmares.33

Our findings show that sleep is a common motivator for alcohol use among women veterans who consume alcohol, and insomnia symptoms are associated with increased risk for alcohol use to aid sleep above and beyond PTSD symptoms. As hypothesized, insomnia severity and PTSD symptoms were independently associated with using alcohol as a sleep aid. Further prospective research is needed to determine whether improved sleep predicts reduction in alcohol use, whether alcohol use needs to be specifically addressed during insomnia treatment among those who are daily drinkers, and whether reduced alcohol use improves sleep for women who are drinking at levels that may interfere with sleep quality, as can happen at heavy levels of alcohol consumption.

Of concern, and consistent with our hypotheses, among women who drink alcohol, having used alcohol to aid sleep was associated with daily drinking. The current recommendation for “low risk” alcohol consumption for women is no more than seven drinks per week (and no more than three drinks on any day);34 women drinking on a daily basis may still be at risk for future alcohol use problems, particularly if they are combining alcohol with medications or have medical or psychiatric problems that are exacerbated by alcohol.

In our sample, > 50% of women reported prescription and/or OTC sleep medication use. 38.1% of women reported using prescription sleep medications, which is substantially higher than general population estimates (4.1 percent of U.S. adults aged 20 years or older), while 23.5% report OTC sleep medication use in the past month.35 Studies to understand why sleeping pill use is so common among women Veterans are needed, particularly in the context of other studies showing that women veterans prefer non-medication approaches over sleeping pills.26 Using alcohol to aid sleep was also associated with increased odds of sleep medication use, which is very concerning because most prescription sleep aids explicitly should not be used with alcohol due to risk of extreme sedation, respiratory depression and the potential for cognitive issues.36,37 Furthermore, combined use of alcohol and medications for sleep (e.g., benzodiazepines) can increase risk of death by overdose.38 The current data do not allow for determining whether sleep medications and alcohol were used concurrently on a given night. Future research is needed for further understanding of how frequently women use both alcohol and sleep aids on a given night and how often they “alternate” between alcohol and sleeping pills. Despite these limitations, our findings do highlight the importance of alcohol use screening in patients who use sleep medications, particularly among women Veterans, who are using sleep medications at much higher rates than women in the general population. Existing research suggests that efforts to screen and intervene with alcohol use through brief interventions in primary care are efficacious.39,40

The current findings also support the importance of addressing sleep difficulties through non-pharmacological means, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I; an evidence-based psychotherapy for the treatment of insomnia disorder),41 and patient education about the impacts of alcohol on sleep quality and about drinking in combination with sleep medications. In our sample, the large number of women who reported taking sleep medications suggest that there is a strong need in this population for sleep medication education and for alternate strategies for improving sleep. Our recent study found that women veterans prefer non-medication treatments for insomnia over medications, suggesting that, if offered, women would likely find CBT-I acceptable.26 Reducing the burden of insomnia among women veterans may reduce the use of alcohol to aid sleep, thus decreasing the risk for lethal substance combinations.

This study has several strengths, including a nationwide sample and inclusion of widely-used screening tools such as the PC-PTSD and ISI. Limitations include the use of self-reported questionnaires, which may specifically lead to response bias underestimation of PTSD symptomology and alcohol use. Alcohol use questions used in this study did not assess alcohol use problems or heavy drinking episodes, and the frequency measure of alcohol use used in the current study may have led to the under-identification of women who are drinking at unhealthy levels based on factors other than drinking frequency (e.g., heavy drinking, but not daily drinking). Measures in the study also did not provide information on use of alcohol and sleep medications in the same time period, and given that data were cross-sectional, we are unable to determine causality. Prospective research on this topic is needed. For these analyses, data were not available on other psychiatric disorders, medical comorbidities, and other substance use. We found some differences between responders and non-responders which may limit generalizability of our findings and highlight populations in need of more targeted recruitment and study, including Hispanic/Latina women veterans and infrequent and younger VA users. In addition, our findings may not generalize to women who are seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder, insomnia or PTSD, or to male veterans or civilian populations. Additional research on this topic outside of the VA healthcare system is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings contribute to understanding how sleep problems, alcohol use and use of sleep medications intersect. Screening women with insomnia for alcohol use, particularly those using prescription sleep aids, may help avoid future alcohol-related problems or dangerous combinations of alcohol with prescription sleep aids. Our results suggest the necessity of assessing for sleep difficulties and inquiring about alcohol use specifically for sleep, even among women who have screened negative for alcohol misuse. This step may identify women at risk for unhealthy alcohol use and may provide an opportunity for education around sleep and alcohol use, particularly for those who mix sleep medications with alcohol.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Chloe Bird, PhD (supported through the VAGLAHS HSR&D Center of Innovation #CIN 13-147) for her feedback on this manuscript and her assistance for putting the findings into the context of healthcare for women veterans. This research was supported by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI; RRP 12-189; PI: Martin); Research Service of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS); and VAGLAHS Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center. Dr. Schweizer was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Women’s Health at the VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy (CIN 13-417). Dr. Hoggatt was funded through a VA HSR&D QUERI Career Development Award (CDA 11-261) at the VAGLAHS. Dr. Yano’s time was funded by a VA HSR&D Service Senior Research Career Scientist Award (Project # RCS 05-195). Dr. Martin was supported by the NIH/NHLBI with a Mentoring award (K24 HL143055).

Declarations:

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

There are no conflicts of interest or competing financial interests to report for any author. This research was supported by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI; RRP 12-189; PI: Martin); Research Service of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS); and VAGLAHS Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center. Dr. Schweizer was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Women’s Health at the VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy (CIN 13-417). Dr. Hoggatt was funded through a VA HSR&D QUERI Career Development Award (CDA 11-261) at the VAGLAHS. Dr. Yano’s time was funded by a VA HSR&D Service Senior Research Career Scientist Award (Project # RCS 05-195). Dr. Martin was supported by the NIH/NHLBI with a Mentoring award (K24 HL143055).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Hamilton AB, Cordasco KM, Yano EM. Women veterans’ healthcare delivery preferences and use by military service era: findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28 Suppl 2:S571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin JL, Schweizer CA, Hughes JM, et al. Estimated Prevalence of Insomnia among Women Veterans: Results of a Postal Survey. Womens Health Issues. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy DA, Arnedt JT. Sleep and substance use disorders: an update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley KA, Badrinath S, Bush K, Boyd-Wickizer J, Anawalt B. Medical risks for women who drink alcohol. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(9):627–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoggatt KJ, Lehavot K, Krenek M, Schweizer CA, Simpson T. Prevalence of substance misuse among US veterans in the general population. Am J Addict. 2017;26(4):357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoggatt KJ, Williams EC, Der-Martirosian C, Yano EM, Washington DL. National prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse in women veterans. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2015;52:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cucciare MA, Lewis ET, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Factors Affecting Women’s Disclosure of Alcohol Misuse in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study with U.S. Military Veterans. Women’s health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 2016;26(2):232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(3):356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. I. Sleep. 1999;22 Suppl 2:S347–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological review. 2004;111(1):33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton AB, Poza I, Washington DL. “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Women’s health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 2011;21(4 Suppl):S203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth T, Workshop P. Does effective management of sleep disorders reduce substance dependence? Drugs. 2009;69 Suppl 2:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Lehavot K, Kaysen DL. Drinking motives moderate daily relationships between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123(1):237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Miner CR, Sen S, Marmar C. Bringing the war back home: mental health disorders among 103,788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(5):476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washington DL, Davis TD, Der-Martirosian C, Yano EM. PTSD risk and mental health care engagement in a multi-war era community sample of women veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(7):894–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barth SK, Kimerling RE, Pavao J, et al. Military Sexual Trauma Among Recent Veterans: Correlates of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaeger D, Himmelfarb N, Cammack A, Mintz J. DSM-IV diagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder in women veterans with and without military sexual trauma. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21 Suppl 3:S65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calhoun PS, Wiley M, Dennis MF, Means MK, Edinger JD, Beckham JC. Objective evidence of sleep disturbance in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of traumatic stress. 2007;20(6):1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes J, Jouldjian S, Washington DL, Alessi CA, Martin JL. Insomnia and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among women veterans. Behavioral sleep medicine. 2013;11(4):258–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nappi CM, Drummond SP, Hall JM. Treating nightmares and insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of current evidence. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Mill JG, Hoogendijk WJ, Vogelzangs N, van Dyck R, Penninx BW. Insomnia and sleep duration in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2010;71(3):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone BM. Sleep and low doses of alcohol. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980;48(6):706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vitiello MV. Sleep, alcohol and alcohol abuse. Addict Biol. 1997;2(2):151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein MD, Friedmann PD. Disturbed Sleep and Its Relationship to Alcohol Use. Substance Abuse. 2006;26(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NIAAA. Harmful Interactions: Mixing alcohol with medicines. In: National Institutes of Health UDoHaHS, ed. Vol NIH Publication No. 13–53292014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culver NC, Song Y, Kate McGowan S, et al. Acceptability of Medication and Nonmedication Treatment for Insomnia Among Female Veterans: Effects of Age, Insomnia Severity, and Psychiatric Symptoms. Clin Ther. 2016;38(11):2373–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agriculture USDoHaHSaUSDo. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.2015.

- 28.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep medicine. 2001;2(4):297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prins A, Oimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2004;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foundation NS. 2005 Sleep in America Poll: Summary of Findings. In. Washington, D.C.: National Sleep Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobie DJ, Maynard C, Kivlahan DR, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder screening status is associated with increased VA medical and surgical utilization in women. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21 Suppl 3:S58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Washington DL, Davis TD, Der-Martirosian C, Yano EM. PTSD risk and mental health care engagement in a multi-war era community sample of women veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):894–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishith P, Resick PA, Mueser KT. Sleep difficulties and alcohol use motives in female rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of traumatic stress. 2001;14(3):469–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(NIAAA) NIoAAaA. Rethinking Drinking: Alcohol and Your Health (Publication No. 13–3770). In: Health NIo, ed. Rockville, MD2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chong Y, Fryar CD, Gu Q. Prescription sleep aid use among adults: United States, 2005–2010. NCHS Date Brief;2013. [PubMed]

- 36.Weathermon R, Crabb DW. Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 1999;23(1):40–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hesse LM, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Clinically important drug interactions with zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon. CNS drugs. 2003;17(7):513–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka E Toxicological interactions between alcohol and benzodiazepines. Journal of toxicology Clinical toxicology. 2002;40(1):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018;2:Cd004148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trauer JM, Qian MY, Doyle JS, Rajaratnam SM, Cunnington D. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Insomnia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2015;163(3):191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]