Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cholesterol is related to improvements in the rate of sustained virological response and a robust immune response against the hepatitis C virus (HCV). APOE gene polymorphisms regulate cholesterol levels modifying the course of the HCV infection. The relationship between cholesterol, APOE alleles, and the outcome of HCV infection has not been evaluated in the admixed population of Mexico.

AIM

To investigate the role of APOE -ε2, -ε3, and -ε4 alleles and the metabolic profile in the outcome of HCV infection.

METHODS

A total of 299 treatment-naïve HCV patients were included in this retrospective study. Patients were stratified in chronic hepatitis C (CHC) (n = 206) and spontaneous clearance (SC) (n = 93). A clinical record was registered. Biochemical tests were assessed by dry chemistry assay. APOE genotypes were determined using a Real-Time polymerase chain reaction assay.

RESULTS

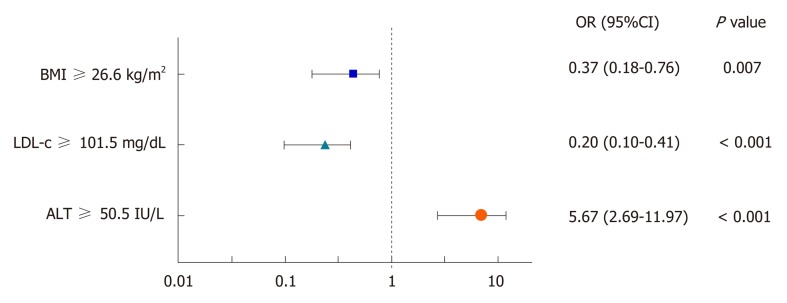

Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), triglycerides, and hypercholesterolemia were higher in SC than CHC patients as well as the frequency of the APOE ε4 allele (12.4% vs 7.3%). SC patients were overweight (54.8%). The ε4 allele was associated with SC (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.31-0.98, P = 0.042) and mild fibrosis (F1-F2) in CHC patients (OR 0.091, 95%CI 0.01-0.75, P = 0.020). LDL-c ≥ 101.5 mg/dL (OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.10-0.41, P < 0.001) and BMI ≥ 26.6 kg/m2 (OR= 0.37, 95%CI: 0.18-0.76, P < 0.001) were associated with SC status; while ALT ≥ 50.5 IU/L was negatively associated (OR = 5.67, 95%CI: 2.69-11.97, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION

In SC patients, the APOE ε4 allele and LDL-c conferred a protective effect in the course of the HCV infection in the context of excess body weight.

Keywords: Liver damage, Body mass index, Spontaneous hepatitis C virus clearance, Low-density lipoprotein, Cholesterol

Core tip: Cholesterol is a metabolic regulator of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) life cycle. Genetic polymorphisms in the APOE gene can regulate cholesterol and modify the outcome of the HCV infection. Our findings suggest that APOE ε4 allele and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) confer a protective effect in the course of the HCV infection in the context of high body mass index (BMI). Levels of LDL-c, BMI, and ALT may estimate the risk of chronicity in HCV-infected patients. An individualized therapy accounting the host´s genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors could aid in the clinical management of HCV infection, especially in populations with a high prevalence of overweight and obesity.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a significant health problem causing chronic liver diseases worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 71 million people are chronically infected, and 399,000 deaths each year are related to HCV infection[1]. Estimates are that up to 90% of the infected individuals are unaware of their status of infection[2]. In approximately 25-30 years, chronic HCV infection may progressively lead to a broad spectrum of clinical outcomes such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and in some cases, hepatocellular carcinoma[3]. However, some patients (20%-40%) may resolve an acute infection by self-spontaneous clearance of the virus, evidenced by positive anti-HCV antibodies and negative viral RNA in the serum[4]. This rate is variable due to a combination of the immunologic, metabolic, and genetic factors of the host[5].

In particular, plasmatic levels of total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) have been reported as predictors of the response to interferon therapy during HCV infection[6]. Likewise, the Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene encoding the glycoprotein component of the low-density lipoprotein has also been implicated in the outcome of HCV infection and associated comorbidities[7]. HCV binds to the ApoE ligand entering the hepatocyte via the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)[8]. Two functional polymorphisms rs429358 and rs7412 in the APOE gene lead to three common alleles, ε2, ε3 and ε4, encoding the corresponding major isoforms, ApoE -E2, -E3 and -E4[9]. ApoE3 is the wild-type isoform with a natural affinity for the LDLR, while ApoE2 and ApoE4 present opposed binding abilities. ApoE2 isoform has a significantly decreased attachment to the LDLR. Conversely, the ApoE4 isoform confers increased binding to LDLR compared to ApoE2 and ApoE3[10]. These relative binding properties are consistent with findings that suggest a protective effect of APOE ε4 in the progression of liver damage as revealed by histopathological analysis[11], whereas APOE ε3 has been associated with the persistence of the infection[12].

There is growing evidence of the occurrence of dyslipidemia in HCV-infected patients[13]. Therefore, changes in body weight may have a meaningful impact on the management of these patients. Currently, Mexico and the United States are experiencing a significant adult obesity health problem[14]. In Mexico, 72.5% of the adult population present overweight or obesity[15]. This increase in body mass index (BMI) is associated with the development of several metabolic abnormalities including dyslipidemias such as, hypercholesterolemia (HChol), which is one of the eight most important risk factors of mortality in Mexico[16]. Both obesity and dyslipidemia are associated with environmental risk factors such as diet. Recently, we described that the dietary pattern of the general Mexican population and HCV-infected patients promote the development of lipid abnormalities[17]. On the other hand, the APOE ε4 allele that is associated with HChol has a heterogeneous prevalence at the national level ranging from 0-20.3%[18]. However, the relationship between APOE alleles and lipid metabolism, as well as its potential implication in HCV infection among the Mexican population is currently unknown.

West Mexico is a region characterized by a genetically admixed population with Amerindian, European, and less extensively African ancestries[19]. Given the variability of APOE alleles observed by ethnicity[20,21], it is plausible that differences in the genetic and environmental factors of the Mexican population may influence the relationship between APOE, lipid abnormalities and outcome of HCV infection. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the role of APOE ε2, - ε3, and - ε4 alleles and the metabolic profile in the outcome of HCV-infected patients in West Mexico.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and study design

In this retrospective study, adult patients who were anti-HCV positive, un-related, and treatment-naive were enrolled from January 2014 to December 2016 at the Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde”. The exclusion criteria were chronic hepatitis B virus infection or human immunodeficiency virus infection, autoimmune disease, Child-Pugh class B and C, Wilson´s disease, hemochromatosis, drinkers, and use of hypolipidemic drugs.

A physician elaborated all medical records in which demographics, clinical data, risk factors for the acquisition of viral hepatitis, and laboratory test results were registered. Patients were serologically tested for anti-HCV antibodies (Third-generation ELISA, AxSYM®, Abbott Laboratories, IL, United States) and quantitative assessment of serum RNA was performed by a standardized quantitative reverse PCR assay (Roche COBAS® AmpliPrep and COBAS® TaqMan 48 HCV test, Pleasanton, CA, United States). After testing, the study population was divided into two groups: Spontaneous clearance (SC) patients (n = 93) who had at least two undetectable serum HCV RNA results in the last 12 months with a six-month interval between each test. Chronic hepatitis C infection (CHC) patients (n = 206) had two detectable serum HCV RNA results during the preceding 12 months with a six-month interval between each test.

Time of evolution was estimated as the elapsed time between the date of diagnosis and first exposure to risk. Patients had not been previously diagnosed at the time of the study.

Anthropometric assessment

Body mass index (kg/m2) was estimated using electrical bio-impedance (InBody3.0, Analyzer Body Composition, Biospace, South Korea). Normal weight was > 18.5-24.99 kg/m2, overweight > 25-29.99 kg/m2 and obesity > 30 kg/m2 as defined by the WHO[22].

Liver stiffness measurement by transitional elastography

Liver stiffness measurement was assessed by a certified physician using transitional elastography (TE) (FibroScan®, Echosens, Paris, France). Liver stiffness was calculated as the median value of ten valid TE measurements expressed in kilopascals (kPa) indicating liver fibrosis according to the following classification: F1, mild fibrosis (7.1-8.7 kPa), F2, moderate fibrosis (8.8-9.4 kPa), F3, severe fibrosis (9.5-12.4 kPa) and F4, cirrhosis (> 12.5 kPa)[23].

Biochemical measurements

Ten mL of blood samples were drawn after a 12-h fast. Biochemical measurements of TC, triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were performed using a Vitros 250 Analyzer (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostic, Johnson & Johnson, Rochester, NY, USA). Commercial control serum and human pooled serum were used to ensure the accuracy of the biochemical measurements. LDL-c concentration was calculated using the Friedewald formula[24], and very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-c) concentration was calculated as TC-(LDL-c + HDL-c). Fasting insulin levels were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Monobind Inc, Texas, United States). The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as the following formula: (fasting insulin (μU/mL) x fasting glucose (mg/dL)/405[25].

Lipid abnormalities

Lipid abnormalities were defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program ATP III criteria and the Mexican Official Norm-037 (NOM-037)[26,27]. Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) ≥ 150 mg/dL, HChol ≥ 200 mg/dL, hypo-alphalipoproteinemia (HALP) ≤ 40 mg/dL for men and ≤ 50 mg/dL for women, high LDL ≥ 130 mg/dL. Insulin resistance was defined as HOMA-IR > 2.5.

APOE genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral whole blood leukocytes using the salting-out method and stored at -80 °C until use. The APOE genotype was determined using a 5’ allelic discrimination method[28]. The reactions were carried out using two TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays (rs429358 C_3084793_20 and rs7412 C_904973_10, Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). Cycle conditions were an initial enzyme activation for 10 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of denaturalization for 15 s at 95 °C and alignment/extension for 1 min at 60 °C in a StepOnePlus thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). Genotypes were verified using positive and negative controls. Twenty percent of the samples were genotyped in duplicate, and 100% of concordance was observed.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± SD and were compared by student´s t-test. Categorical variables are expressed as number and percentage and were analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher´s exact test. The normal distribution of the quantitative variables was tested with Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Shapiro-Wilks test if the number of cases was more or less than 30, respectively. The APOE allelic frequencies were obtained by direct counting method. The Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) expectation was assessed by the software Arlequin version 3.1[29]. The contribution of the APOE alleles to lipid profile in SC and CHC patients was analyzed as APOE genotype groups: E2: ε2ε2 + ε2ε3 + ε2ε4, E3: ε3ε3 and E4: ε3ε4 + ε4ε4.

The variables associated with HCV status were identified using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We also tested the goodness of fit of the regression model using the Hosmer-Lemeshow method[30]. The area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was computed to select the corresponding thresholds for variables associated with SC. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were computed for the selected cutoffs using viral load as a reference variable. Statistical analyses were performed using Epi InfoTM 7.1.2.0 (CDC, Atlanta, USA) and IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. An expert biostatistician revised the statistical analysis.

Ethics

The study protocol complied with the ethical guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board, Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Certificate #CI-00612. All participants signed informed consent before participating in the study.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

The demographic and clinical features of the study population were compared, as shown in Table 1. No significant differences in age, gender, and BMI were found between CHC and SC groups. Risk factors were essentially similar in both groups except for body piercing in SC. Notably, CHC patients were more normal weight than SC (36.4% vs 19.3%, P = 0.003), whereas a higher rate of overweight was observed in SC compared to CHC patients (54.8% vs 42.2%, P = 0.042). HOMA-IR tended to be comparatively higher in CHC than in SC patients (55.4% vs 43.0%, P = 0.072). According to the TE, 62.5% and 29.5% of the SC and CHC patients, respectively had fibrosis stage F1 (P = 0.001). On the other hand, 12.5% and 38.5% of the SC and CHC patients, respectively presented fibrosis stage F4 (P = 0.002). The levels of LDL-c, TC, and TG, as well as the rate of lipid abnormalities (HChol, abnormal LDL-c, and HTG), were higher in SC patients compared to CHC patients (P < 0.001). Conversely, both AST and ALT were significantly increased in CHC patients than SC patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of hepatitis C virus patients, n (%)

| Variable | Chronic, n = 206 | Clearance, n = 93 | P value |

| Demographic and clinical data | |||

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) (range) | 51.0 ± 12.0 (20-78) | 47.1 ± 13.0 (21-74) | 0.100 |

| Female sex | 123 (60) | 48 (52) | 0.236 |

| Time of evolution, yr | 18.0 ± 14.5 | 20.2 ± 15.6 | 0.156 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.0 ± 6.0 | 28.0 ± 4.1 | 0.098 |

| Normal weight | 76 (36.4) | 19 (19.3) | 0.003 |

| Overweight | 87 (42.2) | 51 (54.8) | 0.042 |

| Obesity | 43 (20.8) | 23 (24.7) | 0.456 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 105.6 ± 43.6 | 101.6 ± 33.0 | 0.46 |

| HOMA-IR > 2.5 | 114 (55.4) | 40 (43.0) | 0.072 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 27 (13.1) | 7 (7.5) | 0.183 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| AST, IU/L | 74.2 ± 53.4 | 30.9 ± 14.4 | < 0.001 |

| ALT, IU/L | 76.4 ± 66.7 | 31.5 ± 19.8 | < 0.001 |

| Lipid profile | |||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 148.1 ± 43.3 | 184.1 ± 43.1 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 83.7 ± 37.2 | 112.4 ± 35.4 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 127.7 ± 61.3 | 168.2 ± 80.3 | < 0.001 |

| VLDL-c, mg/dL | 25.8 ± 14.3 | 33.3 ± 15.8 | 0.001 |

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 39.7 ± 13.5 | 41.9 ± 17.7 | 0.766 |

| Lipid abnormality | |||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 20 (9.8) | 30 (32.2) | < 0.001 |

| High LDL-c | 20 (9.7) | 24 (25.8) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 60 (29.1) | 45 (48.3) | 0.001 |

| Hypoalphalipoproteinemia | 85 (41.3) | 44 (47.3) | 0.328 |

| Viral genotype | |||

| HCV genotype 1 | 138 (66.9) | Not determined | - |

| Non-genotype 1 | 68 (33.1) | ||

| Fibrosis stage1 | |||

| F1 | 26 (29.5) | 30 (62.5) | < 0.001 |

| F2 | 19 (21.8) | 11 (22.9) | 0.883 |

| F3 | 9 (10.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0.083 |

| F4 | 33 (38.5) | 6 (12.5) | 0.002 |

| Risk factors for HCV infection | |||

| Surgeries | 144 (69.9) | 62 (66.7) | 0.164 |

| Blood transfusion | 119 (58) | 36 (38.7) | 0.169 |

| Tattooing | 49 (23.7) | 19 (20.4) | 0.375 |

| Dental procedure | 49 (23.7) | 18 (19.3) | 0.28 |

| Sexual promiscuity | 41 (19.9) | 14 (15.0) | 0.702 |

| Acupuncture | 28 (13.5) | 8 (8.6) | 0.464 |

| Injection drug use | 27 (13.1) | 10 (10.7) | 0.932 |

| Body piercing | 4 (1.9) | 8 (8.6) | 0.002 |

Liver damage was assessed in 87 chronic hepatitis C and 48 spontaneous clearance patients. BMI: Body mass index; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

Distribution of APOE alleles, association of APOE ε4 allele with SC and fibrosis stage

Overall, APOE ε4 allele was present in 8.8% of the study population, as shown in Table 2. The frequency of the APOE alleles was concordant with the HWE (P > 0.05). A higher prevalence of the ε4 allele was found in SC (12.4%) compared to CHC (7.3%) patients, and it was associated with an increased likelihood of SC (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.31-0.98, P = 0.042). Also, the APOE ε4 allele was associated with mild fibrosis (F1-F2) in CHC patients (OR = 0.091, 95%CI: 0.01-0.75, P = 0.020). In contrast, the APOE ε3 allele was associated with 2.99-fold risk (95%CI: 1.13-7.87, P = 0.021) for severe liver damage (F3-F4). CHC patient carriers of APOE ε4 allele had lower serum levels of AST and ALT than the APOE ε3 allele carriers (59.7 IU/L vs 79.1 IU/L, P = 0.041 and 53.2 IU/L vs 88.36 IU/L, P = 0.046, respectively) (data not shown).

Table 2.

APOE allele distribution among the study population and stages of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients, n (%)

|

HCV-patients |

Fibrosis stage in CHC patients4 |

|||||

| Chronic (n = 206) | Clearance (n = 93) | P value | F1-F2 (n = 49) | F3-F4 (n = 38) | P value | |

| Genotypes | ||||||

| ε2ε2 | 2 (1.0) | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| ε2ε3 | 15 (7.4) | 8 (8.6) | 0.691 | 5 (10.5) | 2 (5.3) | 0.400 |

| ε2ε4 | 2 (1.0) | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| ε3ε3 | 160 (77.5) | 64 (68.8) | 0.102 | 29 (59.2) | 34 (89.5) | 0.001 |

| ε3ε4 | 26 (12.7) | 19 (20.4) | 0.080 | 14 (28.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| ε4ε4 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.2) | 0.181 | 1 (2) | 1 (2.6) | 0.969 |

| Alleles | ||||||

| ε2 | 21 (5.1) | 8 (4.3) | 0.674 | 4 (5.1) | 2 (2.6) | 0.603 |

| ε3 | 361 (87.6) | 155 (83.3) | 0.158 | 78 (78.6) | 70 (93.4) | 0.0222 |

| ε4 | 30 (7.3) | 23 (12.4) | 0.0421 | 16 (16.3) | 4 (4) | 0.0233 |

| HWE | 0.438 | 0.892 | - | 0.910 | 0.286 | - |

ε4 allele was associated with SC OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.31-0.98, P = 0.042.

ε3 allele was associated with severe fibrosis (F3-F4) OR = 2.99, 95%CI: 1.13-7.87, P = 0.021.

ε4 allele was associated with mild fibrosis (F1-F2) OR = 0.091, 95%CI: 0.01-0.75, P = 0.020.

Liver damage was assessed in 87 chronic hepatitis C patients. CHC: Chronic hepatitis C; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium.

Effect of APOE genotype groups on the lipid profile of CHC and SC patients

In SC patients, being a carrier of the E4 genotype increased the plasma levels of TC and LDL-c (P < 0.05). Meanwhile, in the CHC patients, the E4 genotype increased the levels of HDL-c and the prevalence of HChol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of APOE alleles on lipid profile and lipid abnormalities of hepatitis C virus patients

|

Chronic |

Clearance |

|||||

| E2 (n = 19) | E3 (n = 160) | E4 (n = 27) | E2 (n = 8) | E3 (n = 64) | E4 (n = 21) | |

| Lipid profile | ||||||

| TC, mg/dL | 140.6 ± 34.1 | 150.9 ± 45.7 | 158.3 ± 45.5 | 142.7 ± 40.3 | 184.3 ± 41.43 | 188.9 ± 424 |

| TG, mg/dL | 134.4 ± 78.4 | 130.2 ± 59.6 | 114.2 ± 53.4 | 151.2 ± 81.6 | 169.1 ± 81.1 | 165.8 ± 79.4 |

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 36.9 ± 7.7 | 38.8 ± 12.9 | 45.9 ± 17.61 | 34.7 ± 6.5 | 42.6 ± 21.1 | 42.0 ± 9.7 |

| VLDL-c, mg/dL | 24.3 ± 11.4 | 26.7 ± 15.3 | 22.1 ± 10.0 | 30.1 ± 16.7 | 33.2 ± 15.7 | 33.1 ± 15.9 |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 82.6 ± 29.2 | 85.6 ± 38.2 | 98.7 ± 43.5 | 77.7 ± 29.0 | 110.1 ± 33.15 | 121.6 ± 34.76 |

| Lipid abnormalities, n (%) | ||||||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1 (5.3) | 13 (8.1) | 6 (22.2)2 | 0 | 19 (29.6) | 8 (38.1) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 7 (36.8) | 43 (26.9) | 6 (22.2) | 3 (37.5) | 26 (40.6) | 9 (42.8) |

| Hypoalphalipoproteinemia | 10 (52.6) | 75 (46.9) | 9 (33.3) | 7 (87.5) | 30 (46.9) | 10 (47.6) |

| High LDL-c | 1 (5.3) | 14 (8.7) | 5 (18.5) | 0 | 12 (18.7) | 7 (33.3) |

E4 vs E3, P = 0.033;

E4 vs E3, P = 0.024;

E3 vs E2, P = 0.018;

E4 vs E2, P = 0.014;

E3 vs E2, P = 0.012;

E4 vs E2, P = 0.005. E2: ε2ε2 + ε2ε3 + ε2ε4; E3: ε3ε3; E4: ε3ε4 + ε4ε4. TC: Total cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; Hchol: Hypercholesterolemia; HTG: Hypertriglyceridemia; HALP: Hypoalphalipoproteinemia.

Effect of lipid profile on spontaneous HCV clearance status

Univariate and multivariate analysis of TC, LDL-c, BMI, and other relevant biochemical variables were performed to clarify whether they were related to SC status (Table 4). Multivariable analysis identified LDL-c, BMI, TG, and ALT as significantly associated with SC status (P < 0.05). A ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal threshold values of LDL-c, BMI, TG, and ALT and their association with SC status. For practical applications, sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV were also calculated (Table 5). Finally, the cutoffs were used to convert these variables into dichotomous variables, and a new multivariate analysis was carried out. This final model identified that LDL-c ≥ 101.5 mg/dL and BMI ≥ 26.6 kg/m2 were better predictors of SC, whereas ALT ≥ 50.5 IU/L was negatively associated with SC status (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of variables associated with spontaneous hepatitis C virus clearance

| Variable |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| AST, IU/L | 1.058 | 1.040-1.076 | < 0.001 | |||

| ALT, IU/L | 1.04 | 1.026-1.054 | < 0.001 | 1.037 | 1.019-1.056 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 0.981 | 0.973-0.988 | < 0.001 | 0.977 | 0.963-0.992 | 0.002 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.983 | 0.977-0.989 | < 0.001 | |||

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 0.993 | 0.989-0.996 | < 0.001 | 0.992 | 0.986-0.999 | 0.027 |

| VLDL-c, mg/dL | 0.97 | 0.953-0.987 | 0.001 | |||

| Age, (yr) | 1.024 | 1.003-1.045 | 0.023 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.962 | 0.913-1.013 | 0.138 | 0.874 | 0.790-0.966 | 0.008 |

| Female, sex | 1.358 | 0.833-2.213 | 0.22 | |||

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 0.994 | 0.977-1.011 | 0.481 | |||

Hosmer and Lemeshow test: Chi-square = 4.53, P = 0.806. Only significant variables (P < 0.2) in the univariate analysis were introduced in the multivariate analysis when P < 0.05 was significant. AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; LDL-c: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; VLDL-c: Very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BMI: Body mass index; HDL-c: High density-lipoprotein cholesterol; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Table 5.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis of variables associated with spontaneous hepatitis C virus clearance

| Variable | Cutoff | AUC | P value | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV | NPV |

| ALT, IU/L | 50.5 | .79 | < 0.001 | 62% | 83% | 88% | 52% |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 101.5 | .72 | < 0.001 | 60.7% | 78% | 79% | 58% |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 117.5 | .64 | < 0.001 | 69% | 55% | 78% | 42% |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.6 | .59 | 0.018 | 63% | 54% | 76% | 38.7% |

PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; AUC: Area under the curve; ALT: Alanine transaminase; LDL-c: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BMI: Body mass index.

Figure 1.

Odds Ratio of the multivariate analysis of dichotomous variables associated with spontaneous clearance (95% confidence interval). BMI: Body mass index; LDL-c: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

DISCUSSION

The interplay between lipids/lipoproteins and HCV can modulate HCV infection. For example, cholesterol improves the rate of sustained virological response and immune response against HCV[6]. Also, cell entry is achieved by the virus in the form of lipo-viro-particles associated with ApoE. On the other hand, the three APOE alleles (ε2, ε3, and ε4) portray distinct biological properties that mediate lipid levels by interacting with environmental factors such as diet. These alleles also have a heterogeneous distribution worldwide[20]. Currently, a high prevalence of lipid alterations in the context of the obesity epidemic and an uneven distribution of the APOE alleles is notorious among the Mexican population. These factors prompted us to seek if the differences in the APOE alleles and lipid profile were associated with the outcome of HCV infection. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in reporting the effect of APOE alleles in the course of HCV infection in a Native American-derived population. Our results showed that the APOE allele distribution in the admixed population of West Mexico agrees with our previous work[31], and the overall high frequency of the APOE ε4 allele was consistent with the Native Amerindian ancestry of the study group[32]. However, on further analysis, the prevalence of APOE ε4 allele was higher in SC patients compared to CHC patients and correlated with the lipid profile and fibrosis stage.

Lipo-viro-particles bind to hepatic receptors such as LDLR and Scavenger Receptor class B type 1[33]. In the case of the APOE ε4 allele, it indirectly regulates lipoprotein levels by reducing the expression of LDLR in the hepatocyte surface[34]. Increased LDL-c has been demonstrated in healthy carriers of this allele[35]. In this study, the SC group had a higher ε4 allele prevalence than the CHC patients and was associated with increased levels of TC and LDL-c. These high levels of LDL-c may compete with the lipo-viro-particles for the binding to the LDLR, thus decreasing the entry of the virus. Also, downregulation of the LDLR may hinder viral entry, thus preventing the early stages of infection and diminishing the progression of liver damage.

In agreement with these biological mechanisms mentioned above, in this study, the SC and CHC patients who were ε4 allele carriers also had less liver damage. Furthermore, CHC patients who were carriers of the APOE ε4 allele had the lowest levels of AST and ALT in comparison with the APOE ε3 allele carriers. The protective effect of APOE ε4 found in this study agrees with data reported from other populations with African and European ancestries[11,36,37]. Conversely, APOE ε3 allele was associated with advanced fibrosis in CHC. This observation agrees with previous data reporting that specifically, ApoE ε3 mediates the HCV immune escape mechanism by blocking the innate immunity-activated ficolin-2 protein, thus promoting the progression of the infection[38]. On the other hand, cholesterol and cholesterol derivatives have an immunomodulatory effect against HCV[39,40]. In this study, APOE ε4 increased the levels of total cholesterol and LDL-c in SC patients and the prevalence of HChol in CHC, thus confirming its participation in the modulation of cholesterol in the course of HCV infection as previously reported[37].

An interesting observation was that LDL-c and BMI were the main variables predicting SC status. This finding is concordant with the higher prevalence of overweight in SC than in CHC patients who were mainly normal weight. Overweight and obesity are conditions that lead to lipid alterations of cholesterol and triglycerides that in turn, evoke insulin resistance[41]. In this study, CHC patients tended to have a better lipid profile but depicted a higher level of HOMA-IR than patients with SC. This data is consistent with the higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the CHC patients, in contrast with those who were SC. Moreover, insulin resistance is the hallmark of liver fibrosis. Notably, in this study, the CHC patients who were non-ε4 allele carriers had a higher stage of fibrosis than their peers with SC. Since the levels of LDL-c, BMI, and ALT were the best predictors of SC, these determinants may be used in the early detection of chronicity in HCV-infected patients.

Diet is another crucial interacting factor related to BMI and lipid alterations. Mexico has experienced a nutrition transition in the past three decades, shifting from a traditional food pattern to a westernized diet, a known factor involved in the obesity epidemic[42]. Current diets are hepatopatogenic containing high amounts of simple sugars and saturated fats that result in HChol and hypertriglyceridemia[17,43,44]. Due to this fact and the estimated time of evolution of the patients, we hypothesized that high BMI and cholesterol levels, which are key factors for SC, might have been present at the time of the acute phase of HCV infection, and that some SC patients remained overweight years after clearing the virus. Also, in the context of HCV infection, high levels of LDL-c correlate with interferon sensitivity which is detected by the production of IFN-gamma-induced protein, a chemokine produced by T cells, natural killer cells, and monocytes[45]. Furthermore, high levels of LDL-c are related to interferon sensitivity in genotype 1[46], allowing an adequate innate immune response against HCV that facilitates spontaneous viral clearance. Nevertheless, further investigation is needed to clarify the mechanisms involved in this association as well as designing prospective studies in patients with acute infection.

The relationship between lipid alterations and the dynamics of HCV infection are also influenced by other genetic polymorphisms. In this sense, IFNL4 has been associated with SC by modulating LDL-c levels[47]. CD36 rs1761667 polymorphism was associated with fat perception and advanced fibrosis in Mexican patients with CHC[48]. On the other hand, it may be interesting to investigate if changes in lifestyle such as nutritional interventions could cause cholesterol metabolism disturbances that modify HCV life cycle[44]. In perspective, genetic and environmental factors affecting cholesterol levels may vary significantly worldwide; therefore, we advocate that these factors be considered by population for the management of HCV infection. Furthermore, understanding the molecular mechanisms by which LDL-c is implicated in the course of HCV infection could provide valuable information for controlling HCV infection and limiting its expansion.

In conclusion, APOE ε4 allele and LDL-c confer a protective effect in the course of the HCV infection in the context of high BMI. An individualized therapy accounting the host´s genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors is required to achieve better control of HCV infection, especially in populations with a high prevalence of overweight and obesity.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The interplay between lipids and hepatitis C virus (HCV) can modulate the course of HCV infection. Cholesterol improves the rate of sustained virological response and immune response against HCV. On the other hand, the three APOE alleles mediate lipid levels by interacting with environmental factors such as diet. Currently, a high prevalence of lipid alterations, obesity, and an uneven distribution of the APOE alleles is notorious among the Mexican population. Herein, we investigate the effect of APOE polymorphisms and the lipid profile on the outcome of the HCV infection in patients from Mexico. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in reporting the effect of APOE alleles in the course of HCV infection in a Latin American population.

Research motivation

HCV is a leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide. Although it is expected to be eliminated by 2030, HCV infection still represents an unsolvable problem in many developing countries. At present, the factors impacting on the clinical outcome of HCV infection in Latin American countries are not fully known. Understanding the role of metabolic abnormalities and the participation of cholesterol and APOE polymorphisms in the outcome HCV infection could favor the implementation of earlier strategies of detection and treatment in these populations.

Research objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effect of APOE polymorphisms and the lipid profile on the outcome of the HCV infection in patients with an admixture genetic background living in West Mexico.

Research methods

A total of 299 positive anti-HCV positive patients were enrolled from January 2014 to December 2016. Clinical records were elaborated by a physician. Quantitative assessment of serum RNA was performed by a standardized quantitative reverse PCR assay. After testing, the study population was divided into two groups: Spontaneous clearance (SC) and chronic hepatitis C infection (CHC) patients. Biochemical determinations were tested through a Vitros 250 analyzer, and liver stiffness was assessed by a certified physician using transitional elastography. The APOE genotype was determined using a 5’ allelic discrimination method. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 for windows.

Research results

Patients who presented SC were mainly overweight, had higher levels of total cholesterol, LDL-c, and triglycerides than CHC patients. The APOE ε4 allele was significantly associated with spontaneous HCV clearance status and with less fibrosis than non- ε4 alleles carriers among chronic patients. Levels of LDL-c ≥ 101.5 mg/dL and BMI ≥ 26.6 kg/m2 were associated with SC status; while ALT ≥ 50.5 IU/L was negatively associated.

Research conclusions

The present study suggests that APOE ε4 allele and LDL-c confer a protective effect in the course of the HCV infection in the context of high BMI. Levels of LDL-c, BMI, and ALT may help in the estimation of the risk of chronicity in HCV-infected patients.

Research perspectives

In our view, an individualized therapy accounting the host´s genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors could aid in the clinical management of HCV infection, especially in populations with a high prevalence of overweight and obesity.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Certificate #CI-00612.

Informed consent statement: All participants signed an informed consent before participating in the study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: June 20, 2019

First decision: August 28, 2019

Article in press: September 27, 2019

P-Reviewer: Gencdal G, Kreisel W, Tarantino G S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Karina Gonzalez-Aldaco, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” and Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico.

Sonia Roman, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” and Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico.

Rafael Torres-Valadez, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” and Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico.

Claudia Ojeda-Granados, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” and Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico.

Luis A Torres-Reyes, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” and Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico.

Arturo Panduro, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” and Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico. biomomed@cencar.udg.mx.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) 2019. Hepatitis C. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c cited May 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatzakis A, Wait S, Bruix J, Buti M, Carballo M, Cavaleri M, Colombo M, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Dusheiko G, Esmat G, Esteban R, Goldberg D, Gore C, Lok AS, Manns M, Marcellin P, Papatheodoridis G, Peterle A, Prati D, Piorkowsky N, Rizzetto M, Roudot-Thoraval F, Soriano V, Thomas HC, Thursz M, Valla D, van Damme P, Veldhuijzen IK, Wedemeyer H, Wiessing L, Zanetti AR, Janssen HL. The state of hepatitis B and C in Europe: report from the hepatitis B and C summit conference*. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18 Suppl 1:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrift AP, El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Global epidemiology and burden of HCV infection and HCV-related disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:122–132. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoofnagle JH. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S21–S29. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fierro NA, Gonzalez-Aldaco K, Torres-Valadez R, Martinez-Lopez E, Roman S, Panduro A. Immunologic, metabolic and genetic factors in hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3443–3456. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minuk GY, Weinstein S, Kaita KD. Serum cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels as predictors of response to interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:761–762. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gong Y, Cun W. The Role of ApoE in HCV Infection and Comorbidity. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:pii: E2037. doi: 10.3390/ijms20082037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agnello V, Abel G, Elfahal M, Knight GB, Zhang QX. Hepatitis C virus and other flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12766–12771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wardell MR, Suckling PA, Janus ED. Genetic variation in human apolipoprotein E. J Lipid Res. 1982;23:1174–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol metabolism. Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61:225–232. doi: 10.1007/BF01496128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wozniak MA, Itzhaki RF, Faragher EB, James MW, Ryder SD, Irving WL Trent HCV Study Group. Apolipoprotein E-epsilon 4 protects against severe liver disease caused by hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2002;36:456–463. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price DA, Bassendine MF, Norris SM, Golding C, Toms GL, Schmid ML, Morris CM, Burt AD, Donaldson PT. Apolipoprotein epsilon3 allele is associated with persistent hepatitis C virus infection. Gut. 2006;55:715–718. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.079905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang ML. Metabolic alterations and hepatitis C: From bench to bedside. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1461–1476. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:288–298. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición de Medio Camino (ENSANUT) 2016. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/209093/ENSANUT.pdf cited 29 may 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens G, Dias RH, Thomas KJ, Rivera JA, Carvalho N, Barquera S, Hill K, Ezzati M. Characterizing the epidemiological transition in Mexico: national and subnational burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos-López O, Roman Sonia, Ojeda-Granados C, Sepúlveda-Villegas M, Martínez-López E, Torres-Valadez R, Trujillo-Trujillo E, Panduro A. Patrón de ingesta alimentaria y actividad física en pacientes hepatópatas en el Occidente de México. Rev Endocrinol Nutr. 2013;21:7–15. Available from: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/endoc/er-2013/er131b.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojeda-Granados C, Panduro A, Gonzalez-Aldaco K, Sepulveda-Villegas M, Rivera-Iñiguez I, Roman S. Tailoring Nutritional Advice for Mexicans Based on Prevalence Profiles of Diet-Related Adaptive Gene Polymorphisms. J Pers Med. 2017;7:pii: E16. doi: 10.3390/jpm7040016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martínez-Cortés G, Salazar-Flores J, Fernández-Rodríguez LG, Rubi-Castellanos R, Rodríguez-Loya C, Velarde-Félix JS, Muñoz-Valle JF, Parra-Rojas I, Rangel-Villalobos H. Admixture and population structure in Mexican-Mestizos based on paternal lineages. J Hum Genet. 2012;57:568–574. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abondio P, Sazzini M, Garagnani P, Boattini A, Monti D, Franceschi C, Luiselli D, Giuliani C. The Genetic Variability of APOE in Different Human Populations and Its Implications for Longevity. Genes (Basel) 2019;10:pii: E222. doi: 10.3390/genes10030222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenberg DT, Kuzawa CW, Hayes MG. Worldwide allele frequencies of the human apolipoprotein E gene: climate, local adaptations, and evolutionary history. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143:100–111. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) Country profile indicators. Interpretation guide World Health Organization. 2010 Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/nlis_interpretation_guide.pdf cited 29 may 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lédinghen V, Vergniol J. Transient elastography (FibroScan) Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:58–67. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection; Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-037-SSA2-2012. Para la prevención, tratamiento y control de las dislipidemias. 2012 Available from: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5259329fecha=13/07/2012 cited 29 may 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch W, Ehrenhaft A, Griesser K, Pfeufer A, Müller J, Schömig A, Kastrati A. TaqMan systems for genotyping of disease-related polymorphisms present in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40:1123–1131. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2007;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aceves D, Ruiz B, Nuño P, Roman S, Zepeda E, Panduro A. Heterogeneity of apolipoprotein E polymorphism in different Mexican populations. Hum Biol. 2006;78:65–75. doi: 10.1353/hub.2006.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gamboa R, Hernandez-Pacheco G, Hesiquio R, Zuñiga J, Massó F, Montaño LF, Ramos-Kuri M, Estrada J, Granados J, Vargas-Alarcón G. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism in the Indian and Mestizo populations of Mexico. Hum Biol. 2000;72:975–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto S, Fukuhara T, Ono C, Uemura K, Kawachi Y, Shiokawa M, Mori H, Wada M, Shima R, Okamoto T, Hiraga N, Suzuki R, Chayama K, Wakita T, Matsuura Y. Lipoprotein Receptors Redundantly Participate in Entry of Hepatitis C Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005610. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altenburg M, Johnson L, Wilder J, Maeda N. Apolipoprotein E4 in macrophages enhances atherogenesis in a low density lipoprotein receptor-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7817–7824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610712200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weintraub MS, Eisenberg S, Breslow JL. Dietary fat clearance in normal subjects is regulated by genetic variation in apolipoprotein E. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:1571–1577. doi: 10.1172/JCI113243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomaa HE, Mahmoud M, Saad NE, Saad-Hussein A, Ismail S, Thabet EH, Farouk H, Kandil D, Heiba A, Hafez W. Impact of Apo E gene polymorphism on HCV therapy related outcome in a cohort of HCV Egyptian patients. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2018;16:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mueller T, Fischer J, Gessner R, Rosendahl J, Böhm S, van Bömmel F, Knop V, Sarrazin C, Witt H, Marques AM, Kovacs P, Schleinitz D, Stumvoll M, Blüher M, Bugert P, Schott E, Berg T. Apolipoprotein E allele frequencies in chronic and self-limited hepatitis C suggest a protective effect of APOE4 in the course of hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int. 2016;36:1267–1274. doi: 10.1111/liv.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y, Ren Y, Zhang X, Zhao P, Tao W, Zhong J, Li Q, Zhang XL. Ficolin-2 inhibits hepatitis C virus infection, whereas apolipoprotein E3 mediates viral immune escape. J Immunol. 2014;193:783–796. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.González-Aldaco K, Torres-Reyes LA, Ojeda-Granados C, José-Ábrego A, Fierro NA, Román S. Immunometabolic Effect of Cholesterol in Hepatitis C Infection: Implications in Clinical Management and Antiviral Therapy. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17:908–919. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang Y, Tang JJ, Tao W, Cao X, Song BL, Zhong J. Identification of Cholesterol 25-Hydroxylase as a Novel Host Restriction Factor and a Part of the Primary Innate Immune Responses against Hepatitis C Virus Infection. J Virol. 2015;89:6805–6816. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00587-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klop B, Elte JW, Cabezas MC. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients. 2013;5:1218–1240. doi: 10.3390/nu5041218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivera JA, Barquera S, Campirano F, Campos I, Safdie M, Tovar V. Epidemiological and nutritional transition in Mexico: rapid increase of non-communicable chronic diseases and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:113–122. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramos-Lopez O, Panduro A, Martinez-Lopez E, Roman S. Sweet Taste Receptor TAS1R2 Polymorphism (Val191Val) Is Associated with a Higher Carbohydrate Intake and Hypertriglyceridemia among the Population of West Mexico. Nutrients. 2016;8:101. doi: 10.3390/nu8020101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roman S, Rivera-Iñiguez I, Ojeda-Granados C, Sepulveda-Villegas M, Panduro A. Genome-Based Nutrition in Chronic Liver Disease. In: Watson R, Preedy V. Dietary Interventions in Liver Disease. Foods, Nutrients, and Dietary Supplements. Academic Press, 2019: 3-14. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grebely J, Feld JJ, Applegate T, Matthews GV, Hellard M, Sherker A, Petoumenos K, Zang G, Shaw I, Yeung B, George J, Teutsch S, Kaldor JM, Cherepanov V, Bruneau J, Shoukry NH, Lloyd AR, Dore GJ. Plasma interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) levels during acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;57:2124–2134. doi: 10.1002/hep.26263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheridan DA, Bridge SH, Felmlee DJ, Crossey MM, Thomas HC, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toms GL, Neely RD, Bassendine MF. Apolipoprotein-E and hepatitis C lipoviral particles in genotype 1 infection: evidence for an association with interferon sensitivity. J Hepatol. 2012;57:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark PJ, Thompson AJ, Zhu M, Vock DM, Zhu Q, Ge D, Patel K, Harrison SA, Urban TJ, Naggie S, Fellay J, Tillmann HL, Shianna K, Noviello S, Pedicone LD, Esteban R, Kwo P, Sulkowski MS, Afdhal N, Albrecht JK, Goldstein DB, McHutchison JG, Muir AJ IDEAL investigators. Interleukin 28B polymorphisms are the only common genetic variants associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in genotype-1 chronic hepatitis C and determine the association between LDL-C and treatment response. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:332–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramos-Lopez O, Roman S, Martinez-Lopez E, Fierro NA, Gonzalez-Aldaco K, Jose-Abrego A, Panduro A. CD36 genetic variation, fat intake and liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:1067–1074. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i25.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]