Abstract

High biological value compounds are very important in the food and pharmaceutical sectors. The leading research interests are seeking efficient methods for extracting these substances. The objective of this study was to evaluate different extraction methods to obtain mangiferin and lupeol at preparative scale from leaves and bark of mango tree varieties Ataulfo and Autochthonous from Nayarit, Mexico. Four extraction techniques were evaluated such as maceration, Soxhlet, sonication (UAE) and microwave (MAE). Sonication gave the highest concentration of mangiferin and lupeol, demonstrating that extraction assisted by ultrasound could be an effective alternative to conventional extraction techniques because it is a low cost, simple and reliable process. Finally, mangiferin and lupeol were obtained at preparative scale with a higher concentration of bioactive compounds, 1.45 g 100 g−1 y 0.92 mg 100 g−1 sample on (d.b.), respectively. The barks from Ataulfo and Autochthonous mango trees turned out to be favourable sources for obtaining mangiferin and lupeol.

Keywords: Mango leaves, Mango bark, Assisted extraction, Mangiferin, Lupeol, Preparative scale

Introduction

Bioactive compounds have gained importance in the food and pharmaceutical markets for their antioxidant activity potential and because they produce some beneficial effects on human health. Mango tree has been the focus of many scientists in search of potent antioxidants, as the handle portions, such as stem bark, leaves, skin and pulp are known for various biomedical applications, including radical free capture and antioxidants (Ajila et al. 2007). Several studies had reported a variety of bioactive compounds such as mangiferin and lupeol in bark and leaves from different varieties of mango trees. These compounds have been classified as preventives for cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, diabetes and cancer diseases (Ajila et al. 2007). Studies concerning the immunomodulatory activity of mangiferin had shown that this xanthone glucoside (1,3,6,7-tetrahidroxixantona) present in fruit mango, modulates expression of several genes involved in the regulation of apoptosis, viral replication, tumorigenesis, inflammation and in autoimmune diseases. These results suggest their potential utility in treatments as inflammatory and/or cancer (Saha et al. 2016). It has been shown that mangiferin protects human lymphocytes of lesions in DNA when exposed to gamma radiation, this raises the possibility of their use in patients undergoing radiotherapy or people occupationally exposed to radiation (Jagetia and Venkatesha 2006). Then, the evidence indicates that mangiferin is a promising chemo-preventive (Rajendran et al. 2008), with bioactivity involving antioxidant (Rodríguez et al. 2006) and modulation of gene expression (Wilkinson et al. 2008).

Similarly, several studies have shown that lupeol exhibit pharmacological activity against various diseases, such as inflammation, arthritis, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, renal disorders, hepatic toxicity, microbial infections and cancer (Sudhahar et al. 2008). Additionally, toxicological studies in animals at doses from 30 to 2000 mg kg−1 had emphasize lupeol is nontoxic and does not cause any systemic toxicity in animals (Murtaza et al. 2009).

The functional properties of food and vegetables require studies to increase the extraction yield, as well as to develop environmental friendly methods, for the extraction of these compounds (Chemat et al. 2017). This interest has led research for new extraction methods, as sonication (UAE) and microwave (MAE), to obtain the metabolites of interest from vegetable materials (Djilani et al. 2006; Bucar et al. 2013) in order to obtain higher extraction yields than traditional methods, such as Soxhlet and maceration extraction (Chemat et al. 2017).

Therefore, this research focuses on the comparison of conventional and non-conventional methods for obtaining mangiferin and lupeol at preparative scale from leaves and bark of mango varieties, namely Ataulfo and Autochthonous grow in Nayarit, Mexico.

Materials and methods

Raw material

Leaves and bark from two mango varieties, Ataulfo and Autochthonous, were collected manually in county of 5 de Mayo, Nayarit, Mexico. The largest and greenest leaves were aleatory chosen. Sections of approximately 10 × 2 and 2 × 1 cm of bark were taken from the trunk and from the branches, respectively. Material was washed and selected avoiding physical or microbiological damage.

Preparation of raw material

Samples of leaves and bark were frozen at − 80 °C and lyophilized at − 50 °C and 0.12 mbar in a Freezone 4.5 (Kansas, USA), until 3% moisture (d.b.) (24 and 48 h for the leaves and bark, respectively). Dried samples were homogenized using a commercial homogenizer GX4100 (Krups, Cd. de Mexico, Mexico) de 200 W.

Extraction of bioactive compounds

The extraction of bioactive compounds was carried out by two conventional methods, maceration and heating, and two non-conventional methods, sonication and microwave. According to Ruiz-Montañez et al. (2014); the mix ethanol-water (8:2 v/v) and hexane were used as solvents for mangiferin and lupeol extraction, respectively, both at a ratio of 1:10 (g sample:ml solvent), except for the heating method (1:20; g sample:ml solvent).

Maceration extraction

A cold maceration was applied, 10 g of freeze-dried powder were mixed with the solvent in an Erlenmeyer flask, agitated during 24 h on an orbital shaker 290400 (Boekel Scientific, Pannsylvania, USA), at 200 rpm and 25 °C, in order to increase the solubility of the material and the mass transfer rate (Aspé and Fernández 2011).

Heating extraction

This extraction was carried out in a continuous Soxhlet extractor VH-6 (NOVATECH, Guadalajara, Mexico). 200 ml of solvent were placed in a 250 ml ball flask and 10 g sample in the extraction chamber. The extraction was carried out by successive washing for 8 h (Aspé and Fernández 2011).

Sonication extraction

10 g of sample were added to the solvent at 25 °C, then treated in a sonicator ultrasonic Cleaner 1510 (Branson, St Louis, USA) by applying a constant frequency of 42 kHz for 30 min in a cold bath. The solid and liquid particles vibrate and are accelerated by ultrasonic action; as a result, the solute passes quickly from the solid phase to the solvent to extract bioactive compounds (Aspé and Fernández 2011).

Microwave

10 g of the sample were placed in contact with the solvent in a flask and exposed to the radiation in a conventional microwave at 600 W (Ruiz-Montañez et al. 2014). The extraction was carried out for 1 min in 30 s irradiation cycles and samples were cooled for 10 min in order to maintain 25 °C as the working temperature.

Extract concentration

The extract was filtered through filter paper (Whatman No.1). A rotary evaporator R-205 (Buchi, New Castle, USA), at 40 °C and 150 rpm to obtain the concentrated extract was used. Finally, the concentrated extracts were deodorized with nitrogen to ensure solvent-free extracts (Ruiz-Montañez et al. 2014).

Quantitative determination of bioactive compounds

Analysis was performed according to Ruiz-Montañez et al. (2014); using HPLC 1525 (Water, Massachusetts, USA), with binary pump and UV detector. The separation was carried out in a C-18/ODSHXPERSIL column (5 µm and 250 × 4.6 µm) at 25 °C. Eluent phase for mangiferin quantification consisted of the solvent A (3% acetic acid in water) and the solvent B (acetonitrile) 10 μl of sample were injected and a solvent flow of 1 ml min−1 for 16 min was used. The program was carried out in gradient starting with 90% eluent A and 10% B, then 6 min from 20% solvent A and 80% B, and finally 10 min with 90% A and 10% eluent B. Mangiferin was detected at 254 nm wavelength.

The mobile phase for lupeol quantification was methanol in an isocratic program, using an injection volume of 10 μl and methanol flow rate of 0.9 ml min−1 for 15 min. Lupeol was detected at 210 nm wavelength. Compounds were quantitated by calibration curve with standards of mangiferin and lupeol (Sigma-Aldrich, 95%, Misuri, USA).

Purification of bioactive compounds

Evaluation of purification resins for mangiferin

Mangiferin purification was carried out in a system of open spine, synthetic resins AMBERLITA XAD7HP and SEPABEADS SP825L were used (Berardini et al. 2005). The sample (10 g) purification was carried out using ethanol:water (5:5) for 30 min, samples were filtered through Whatman No.1 filter paper and ethanol concentrated on a rotary evaporator Buchi, model R-205, at 40 °C and 150 rpm. The resin got in touch with the final extraction (1:1 v/v) and stirred for 2 h at 200 rpm on a rotary shaker. The mixture was filtered and the mother liquor was obtained. The retained was washed with 50 ml of ethyl acetate, stirred for 10 min and finally filtered. The new retentive underwent a second washing with 50 ml of ethyl acetate, stirred at 40 °C for 10 min and finally filtered. Posterior identification of the compounds was carried out in thin layer chromatography (TLC) at 25 °C and finally, mangiferin was quantified by HPLC.

Evaluation of purification resins for lupeol

Lupeol purification was carried out on a glass column 30 cm long and 5 cm in diameter packed with a ratio 1:20 (g extract: g support) using silica gel resin. The mobile phase was hexane: ethyl acetate in polarity descendant (98:2–92:8). Separation was achieved applying vacuum with a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Fractions of 15 ml were taken. The identification of lupeol was performed in TLC and quantification was conducted by HPLC.

Mangiferin and lupeol obtention at preparative scale

This procedure was performed using the most efficient extraction method, and the variety and source where the highest concentration of mangiferin and lupeol were used. 200 g of sample were used to obtain a greater quantity of each of the bioactive compounds.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Analysis of results was performed by ANOVA followed by comparison of means (LSD, p < 0.05), with STATGRAPHICS Centurion XVIII software, Virginia, USA. The response variable was the amount of extract obtained from the leaves and bark of mango varieties Ataulfo and Autochthonous. All determinations were performed in triplicate.

Results and discussion

Mangiferin and lupeol extraction

Concerning the extraction methods for mangiferin, a higher quantity of extract was obtained by heating and sonication methods (Table 1). No significant statistical differences were obtained between these two methods. Considering other process factors, such as solvent amount and extraction time, results showed that the extraction assisted by sonication is more suitable than heating method. Ultrasound required only 30 min and 100 ml of solvent and heating required 8 h and 200 ml of solvent to obtain the extracts. In addition, the advantages of using ultrasound assisted extraction is the feasibility to be scaled to an industrial process.

Table 1.

Extract obtained in leaf and bark of varieties Ataulfo and autochthonous, by four different extraction methods

| Source | Variety | Extraction methods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | Heating | Sonication | Microwave | ||

| Obtained extract g 10 g−1 sample | |||||

| Obtained extract using ethanol-water (8:2 v/v) solvent | |||||

| LEAF | Ataulfo | 2.2 ± 0.14ay | 3.35 ± 0.07ax | 3.5 ± 0.14ax | 2.25 ± 0.07ay |

| Autochthonous | 2.1 ± 0.28ay | 2.75 ± 0.21bx | 2.65 ± 0.07bx | 1.8 ± 0.14by | |

| BARK | Ataulfo | 1.7 ± 0.14bx | 1.80 ± 0.14cx | 1.9 ± 0.28cx | 1.75 ± 0.07bx |

| Autochthonous | 1.7 ± 0.28bx | 1.95 ± 0.07cx | 1.8 ± 0.14cx | 1.75 ± 0.2bx | |

| Obtained extract using hexane solvent | |||||

| LEAF | Ataulfo | 0.15 ± 0.07abxy | 0.15 ± 0.01ay | 0.2 ± 0.02ax | 0.15 ± 0.07axy |

| Autochthonous | 0.2 ± 0.01ay | 0.1 ± 0.01by | 0.25 ± 0.04ax | 0.25 ± 0.07ax | |

| BARK | Ataulfo | 0.1 ± 0.01bx | 0.075 ± 0.03bcx | 0.1 ± 0.01bx | 0.075 ± 0.03bx |

| Autochthonous | 0.1 ± 0.01bx | 0.05 ± 0.01cy | 0.1 ± 0.01bx | 0.1 ± 0.02bx | |

a–c: values followed by the same letter are not significantly different at p > 0.05 about varieties

x–y: values followed by the same letter within a row are not significantly different at p > 0.05 about extraction method

The lupeol extraction shown significant statistical differences between extraction methods. In general, the highest amounts of lupeol were obtained by sonication and microwave methods (Table 1), These results confirm, that new methods for extraction are more advantageous respect to traditional or conventional methods in terms of yields, processing time and solvents volume used.

Gao and Liu (2005) conducted a flavonoids extraction from Saussurea Medusa Maxim, a traditional Chinese herb and concluded that ultrasonic assisted extraction has advantages of efficiency and simplicity over traditional methods such as solvent extraction at 25 °C, thermal and Soxhlet reflux. According to this study, the ultrasound has efficiency 70 times greater than the solvent extraction, 11 times the extraction by distillation and 35 times greater than the Soxhlet extraction. Ruiz-Montañez et al. (2014), also reported ultrasound extraction as a better method to obtain mangiferin and lupeol from Ataulfo and Autochthonous mango pulp and peel.

Quantification of mangiferin and lupeol

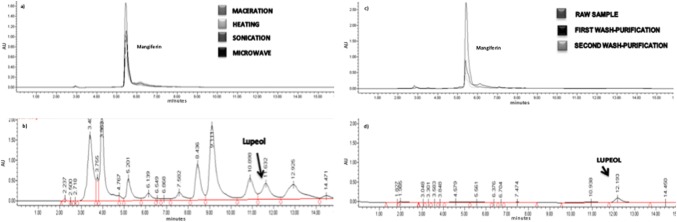

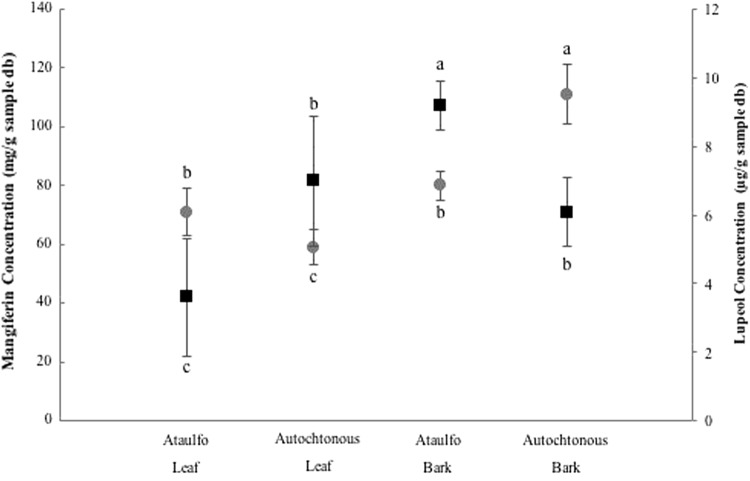

The content of mangiferin and lupeol in the leaves and bark in Autochthonous and Ataulfo varieties of mango tree obtained by the different extraction methods were identified and quantified. Mangiferin is the compound found and extracted in higher concentration in mango tree compared to lupeol concentration (Fig. 1a, b). This fact has been previously referred by Berardini et al. (2005), Barreto et al. (2008) and Ruiz-Montañez et al. (2014). The existence of other compounds with similar polarity to manguiferin and lupeol was reflected (Fig. 1). Mangiferin has been reported as one of the main compounds from mango (Berardini et al. 2005; Barreto et al. 2008). Several studies shown that bark, leaves and peel mango are important sources for extraction of this compound with higher concentration than in the mango pulp (Ribeiro et al. 2008). In this study, the highest concentration of mangiferin obtained was 112.83 mg g−1 (d.b.) in Autochthonous bark by sonication extraction method, this concentration represents 11.28% w/w of dry sample (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Quantification by HPLC of bioactive compounds a mangiferin in Autochthonous bark by four extraction methods, b lupeol in Autochthonous bark by sonication, c mangiferin purification and d lupeol purification

Fig. 2.

Concentrations of mangiferin (filled circle) and lupeol (filled square) obtained in leaf and bark of varieties Ataulfo and Autochthonous by ultrasound method

The aqueous extract of Mangifera indica L., used as an antioxidant in Cuba under the brand Vimang®, has the xanthone mangiferin as the predominate component (10%). This important extract in the pharmaceutical formulation is obtained from the mango bark by aqueous decoction (Núñez Sellés et al. 2002). Hernandez et al. (2007) obtained an ethanolic extract from mango tree bark and leaves, containing 1.2 and 0.17 mg of mangiferin g−1 of sample (d.b.), respectively.

Barreto et al. (2008) characterized and quantified polyphenolic compounds in leaf, bark, and peel from Brazilian mangos. Soxhlet extraction method and methanol were used. The obtained mangiferin in bark 107 g kg−1, young leaves 172 g kg−1 and old leaves 94 g kg−1 are similares to those obteined in this study.

Ribeiro et al. (2008), affirmed that mangos growing under natural conditions contain higher mangiferin concentration, due not only to genetic characteristics, but also to agricultural practices. Thus, it would be an important factor to consider when finding a higher concentration of mangiferin in Creole crust, because these trees grow in natural conditions, without receiving fertilizers or any pesticides.

Conversely, a concentration of 9.2 µg of lupeol g−1 sample (d.b.) in Ataulfo bark by the method of sonication was obtained (Fig. 2). This concentration is low comparated with these obtained from others fruits such as olive fruit (3 mg g−1), aloe leaf (280 mg g−1 of dry leaf), plant elm (800 mg g−1 bark), Japanese Pear (175 mg g−1 branch bark) and Ginseng oil (15.2 mg 100 g−1 of oil) (Saleem 2009).

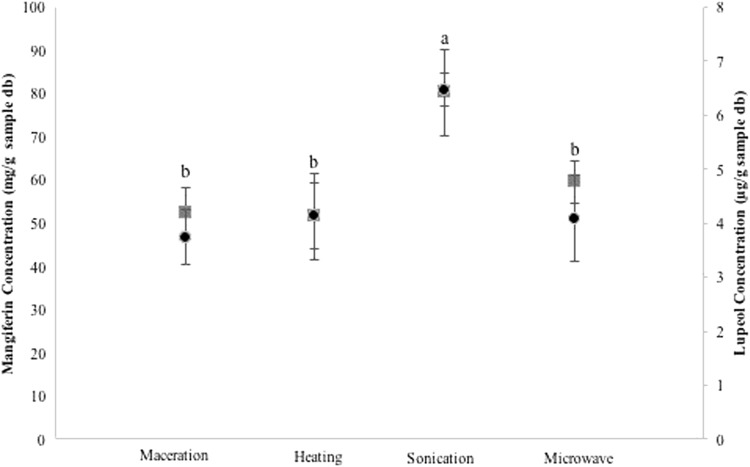

The extraction methods shown statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), and the method assisted by sonication gave the highest yield in mangiferin and lupeol extractions (Fig. 3). Several authors have considered this advantageous treatment due to reduced processing time, with lower energy consumption and to be friendly to the environment (Tiwari et al. 2008; Chemat et al. 2017). Sonication induces a microcurrent that improves material transfer produced in the cavitation bubble collapse, the cell wall is damaged, thus providing a better contact and interaction of solvents and plant materials (Ashokkumar and Mason 2007; Feng, et al. 2011).

Fig. 3.

Average concentration for mangiferin (filled circle) and lupeol (filled square) the four extraction method in leaf and bark of the two varieties (means with unequal letter are significantly different at a value of P < 0.05)

Wang and Weller (2006) reported that ultrasound treatments are inexpensive, simple, reliable and can be an effective alternative to conventional extraction techniques. These authors have also stated that one of the main features of the use of ultrasound treatment in a solid-liquid extraction is to improve extraction efficiency and, as in the Soxhlet extraction may be used a wide range solvent for the extraction of natural bioactive compounds. Thus, the obtained results, in this research let as to demonstrate that the ultrasound method is more efficient for the extraction of bioactive compounds. This behavior was also reported by (Ruiz-Montañez et al. 2014).

Purification de mangiferin and lupeol

According to the results of the qualitative and quantitative determination of target compounds, the purification of bioactive compounds was performed using the best conditions regarding extraction method, variety and source such as Autochthonous bark to mangiferin and Ataulfo bark to lupeol, by ultrasound method.

A statistically significant difference between the resins (SEPABEADS SP825L and AMBERLITE XAD7HP) was observed. The better results with SP825L SEPABEADS resin were obtained. The concentration recovery of mangiferin was between 5.6 and 6.8 mg g−1 of sample (d.b.) after the first wash. In the second wash 1.1–1.7 mg g−1 of sample (d. b.) were recovered and a lower desorption compound was obtained in the third (< 0.5 mg g−1 of sample (d.b.) (Fig. 1c). In a purification process, the adsorption and desorption related to resin polarity and the characteristics of the solute are very important factors (Zhao et al. 2011).

265 ml of each mobile phase were used for the purification of lupeol in open column and 39 fractions of 15 ml each were collected. Lupeol was identified and separated in fractions from 18 to 23, these fractions were mixed and then quantified by HPLC (Fig. 1d).

The quantification of lupeol in Ataulfo bark fraction obtained in the purification by open column, gave good results since the compound separation and recovery was achieved almost at 100% (Fig. 1d).

Preparative scale to obtain mangiferin and lupeol

The preparative scale extraction of lupeol and mangiferin was the way to evaluate the efficiency of the selected extraction method. Higher yields were obtained in the extraction of mangiferin and lupeol (Table 2), considering that mangiferin is one of the major phytochemical components of this fruit (Ruiz-Montañez et al. 2014). The amounts obtained using ultrasound extraction are appropriated. The ultrasound extraction has been reported as an extraction technique that improves the efficiency, increases yield and shortens extraction time of secondary metabolites of various plant tissues, such as cut tea leaves, mint, sage, chamomile, ginseng, arnica, and gentian (Hemwimol et al. 2006). Results showed that the extraction of mangiferin and lupeol from mango tree bark from Nayarit, Mexico is a promising alternative for obtaining value-added products that could be considered for future applications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mangiferin and lupeol concentration on dry basis by preparative scale

| g sample used to extract | Mangiferin | Lupeol |

|---|---|---|

| g mangiferin | mg lupeol | |

| 10 | 0.11283 ± 0.4 | 9.2E−03 ± 7.2E−04 |

| 200 | 2.89 ± 0.35 | 1.83 ± 0.53 |

Conclusion

The ultrasound method is more efficient and workable with respect to other studied methods for the extraction of bioactive compounds. Autochthonous and Ataulfo mango bark are favourable sources for obtaining mangiferin, giving an added value to by-products obtained from the Autochthonous and Ataulfo mango trees pruning. The developed preparative scale by ultrasound extraction method gives important information for future industrial applications. This study suggests the possibility of obtaining HBVC from several vegetable sources using the technique of ultrasound-assisted extraction; as well as the possibility of scaling the process.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ajila CM, Bhat SG, Prasada Rao UJS. Valuable components of raw and ripe peels from two Indian mango varieties. Food Chem. 2007;102:1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashokkumar M, Mason TJ. Sonochemistry. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aspé E, Fernández K. The effect of different extraction techniques on extraction yield, total phenolic, and anti-radical capacity of extracts from Pinus radiata Bark. Ind Crops Prod. 2011;34:838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto JC, Trevisan MTS, Hull WE, et al. Characterization and quantitation of polyphenolic compounds in bark, kernel, leaves, and peel of mango (Mangifera indica L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:5599–5610. doi: 10.1021/jf800738r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardini N, Fezer R, Conrad J, et al. Screening of mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars for their contents of flavonol O- and xanthone C-glycosides, anthocyanins, and pectin. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1563–1570. doi: 10.1021/jf0484069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucar F, Wube A, Schmid M. Natural product isolation-how to get from biological material to pure compounds. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:525–545. doi: 10.1039/c3np20106f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemat F, Rombaut N, Sicaire AG, et al. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;34:540–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djilani A, Legseir B, Soulimani R, et al. New extraction technique for alkaloids. J Braz Chem Soc. 2006;17:518–520. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532006000300013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Barbosa-Cánovas GV, Weiss J. Ultrasound technologies for food an bioprocessing. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Liu CZ. Comparison of techniques for the extraction of flavonoids from cultured cells of Saussurea medusa Maxim. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;21:1461–1463. doi: 10.1007/s11274-005-6809-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemwimol S, Pavasant P, Shotipruk A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of anthraquinones from roots of Morinda citrifolia. Ultrason Sonochem. 2006;13:543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez P, Rodriguez PC, Delgado R, Walczak H. Protective effect of Mangifera indica L. polyphenols on human T lymphocytes against activation-induced cell death. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagetia GC, Venkatesha VA. Mangiferin protects human peripheral blood lymphocytes against γ-radiation-induced DNA strand breaks: a fluorescence analysis of DNA unwinding assay. Nutr Res. 2006;26:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2006.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza I, Saleem M, Adhami VM, et al. Suppression of cFLIP by lupeol, a dietary triterpene, is sufficient to overcome resistance to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in chemoresistant human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1156–1165. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez Sellés AJ, Vélez Castro HT, Agüero-Agüero J, et al. Isolation and quantitative analysis of phenolic antioxidants, free sugars, and polyols from mango (Mangifera indica L.) stem bark aqueous decoction used in Cuba as a nutritional supplement. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:762–766. doi: 10.1021/jf011064b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran P, Ekambaram G, Sakthisekaran D. Cytoprotective effect of mangiferin on benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung carcinogenesis in Swiss albino mice. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;103:137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro SMR, Barbosa LCA, Queiroz JH, et al. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of Brazilian mango (Mangifera indica L.) varieties. Food Chem. 2008;110:620–626. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez J, Di Pierro D, Gioia M, et al. Effects of a natural extract from Mangifera indica L, and its active compound, mangiferin, on energy state and lipid peroxidation of red blood cells. Biochim Biophys Acta: Gen Subject. 2006;1760:1333–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Montañez G, Ragazzo-Sánchez JA, Calderón-Santoyo M, et al. Evaluation of extraction methods for preparative scale obtention of mangiferin and lupeol from mango peels (Mangifera indica L.) Food Chem. 2014;159:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Sadhukhan P, Sinha K, et al. Mangiferin attenuates oxidative stress induced renal cell damage through activation of PI3 K induced Akt and Nrf-2 mediated signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2016;5:313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M. Lupeol, a novel anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer dietary triterpene. Cancer Lett. 2009;285:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhahar V, Ashok Kumar S, Varalakshmi P, Sujatha V. Protective effect of lupeol and lupeol linoleate in hypercholesterolemia associated renal damage. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;317:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9786-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari BK, Muthukumarappan K, O’Donnell CP, Cullen PJ. Effects of sonication on the kinetics of orange juice quality parameters. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:2423–2428. doi: 10.1021/jf073503y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Weller CL. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;17:300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2005.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson AS, Monteith GR, Shaw PN, et al. Effects of the mango components mangiferin and quercetin and the putative mangiferin metabolite norathyriol on the transactivation of peroxisome proliterator-activated receptor isoforms. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:3037–3042. doi: 10.1021/jf800046n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Dong L, Wu Y, Lin F. Preliminary separation and purification of rutin and quercetin from Euonymus alatus (Thunb.) Siebold extracts by macroporous resins. Food Bioprod Process. 2011;89:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2010.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]