Abstract

Background:

Complex interaction of genetic defects with environmental factors seems to play a substantial role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Accumulating data implicate a potential role of disturbed tryptophan metabolism in IBD. Kynurenic acid (KYNA), a derivative of tryptophan (TRP) along the kynurenine (KYN) pathway, displays cytoprotective and immunomodulating properties, whereas 3-OH-KYN is a cytotoxic compound, generating free radicals.

Methods:

The expression of lymphocytic mRNA encoding enzymes synthesizing KYNA (KAT I–III) and serum levels of TRP and its metabolites were evaluated in 55 patients with IBD, during remission or relapse [27 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 28 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD)] and in 50 control individuals.

Results:

The increased expression of KAT1 and KAT3 mRNA characterized the entire cohorts of patients with UC and CD, as well as relapse–remission subsets. Expression of KAT2 mRNA was enhanced in patients with UC and in patients with CD in remission. In the entire cohorts of UC or CD, TRP levels were lower, whereas KYN, KYNA and 3-OH-KYN were not altered. When analysed in subsets of patients with UC and CD (active phase–remission), KYNA level was significantly lower during remission than relapse, yet not versus control. Functionally, in the whole groups of patients with UC or CD, the TRP/KYN ratio has been lower than control, whereas KYN/KYNA and KYNA/3-OH-KYN ratios were not altered. The ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN increased approximately two-fold among all patients with CD; furthermore, patients with CD with relapse, manifested a significantly higher KYNA/3-OH-KYN ratio than patients in remission.

Conclusion:

The presented data indicate that IBD is associated with an enhanced expression of genes encoding KYNA biosynthetic enzymes in lymphocytes; however, additional mechanisms appear to influence KYNA levels. Higher metabolic conversion of serum TRP in IBD seems to be followed by the functional shift of KYN pathway towards the arm producing KYNA during exacerbation. We propose that KYNA, possibly via interaction with aryl hydrocarbon receptor or G-protein-coupled orphan receptor 35, may serve as a counter-regulatory mechanism, decreasing cytotoxicity and inflammation in IBD. Further longitudinal studies evaluating the individual dynamics of TRP and KYN pathway in patients with IBD, as well as the nature of precise mechanisms regulating KYNA synthesis, should be helpful in better understanding the processes underlying the observed changes.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, HPLC, kynurenine pathway, PCR, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of gastrointestinal disorders represented by Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), with a worldwide prevalence surpassing 0.3%.1 Alternating periods of relapse and remission lead to a poor quality of life and require long-term pharmacological or surgical intervention.2 Despite the availability of novel drugs, optimal therapy completely eliminating the symptoms of IBD is lacking, and future research aimed to elucidate underlying causes and to develop novel therapeutic options is needed. A number of hereditary, environmental and microbial factors seem to be linked with the development of IBD; however, the pathogenesis of disease remains to be clarified.3–5 Epidemiological and clinical studies suggest a strong correlation of IBD with genetic predisposition and indicate its polygenic nature.6 More than 230 disease loci, associated mainly with microbiological defence mechanisms, autophagy and immune response, were related with IBD, yet they account for only 20–25% of the heritability.4,6 Accumulating data suggest that a complex interaction of genetic defects with other factors including lifestyle, diet, environmental pollution or disturbed intestinal microbiota, play a substantial role in the pathogenesis of IBD.4,6,7

Metabolic degradation of tryptophan (TRP), an essential neutral amino acid, leads to biosynthesis of several neuroactive and immunoactive molecules. The kynurenine (KYN) pathway, which provides >90% of TRP metabolism in mammals, is an important source of substances regulating the immune response.8 Anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective compounds such as kynurenic acid (KYNA), as well as metabolites acting in a proinflammatory manner, generating free radicals or acting in a directly cytotoxic manner, such as 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-OH-KYN) and quinolinic acid (QUIN), are produced along two separate arms of the KYN pathway.8

KYNA is the most pleiotropic molecule among TRP metabolites. As a broad-spectrum antagonist of glutamate receptors, displaying high affinity for the glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate complex, KYNA was shown to counteract cytotoxicity in various experimental paradigms.9 Furthermore, KYNA as an endogenous ligand of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and G-protein-coupled receptor 35 (GPR35), can display anti-inflammatory actions.8,9 Peripheral KYNA is produced enzymatically, mostly, although not exclusively, in the process of transamination of KYN by aminotransferases (KATs) I–IV.10,11 In the periphery, synthesis of KYNA occurs in a variety of cells and tissues, including endothelial and epithelial cells, fibroblasts, leukocytes, erythrocytes or myocytes.12,13

Recent studies implicate the altered KYN pathway in the pathogenesis of IBD14,15 The contribution of KYNA to intestinal mucosal defence, as well as its role in the modulation of intestinal motility and the inflammatory response were postulated.16,17 The status of TRP metabolism and KYNA in IBD has been the subject of a few studies performed on small and large cohorts, but the available data are not conclusive. An increased serum level of KYNA in patients with IBD,14 a positive correlation of the KYNA/TRP ratio with severity of inflammation in CD18 as well as low serum TRP in IBD and reduced KYNA in patients with CD 19 were demonstrated. Considering the inflammatory nature of IBD, the function of immunocompetent cells, including lymphocytes, has been intensively examined in the specimens obtained from patients with IBD. However, although it is generally accepted that IBD is as a systemic autoimmune disorder,20 relatively less is known about the changes in peripheral population of lymphocytes in the course of disease. Furthermore, acquisition of blood samples in contrast to biopsy specimens is simple, low-cost and an almost stress-free procedure. Thus, we have aimed to study the specific aspects of KYN pathway metabolism in blood from the cohort of patients with IBD in comparison with healthy individuals. Considering that, up to our knowledge, there are no available data on the expression of mRNA encoding KAT I–III in IBD, we analysed the expression of KAT I [glutamine transaminase K/cysteine conjugate β-lyase (CCBL1)], KAT II [aminoadipate aminotransferase (AADAT)] and KAT III (CCBL2) in lymphocytes from patients with IBD. We also compared serum levels of four major TRP–KYN pathway metabolites in patients with CD or UC, during remission or relapse.

Materials and methods

Study population

A total of 55 patients with IBD and 35 healthy individuals were enrolled in the study between 2014 and 2016. Patients were recruited at the Gastroenterology Clinic of the Cardinal Stefan Wyszynński Voivodship Specialist Hospital in Lublin, Poland. The CD group (n = 27) included 13 females and 14 males (average age = 34.7 ± 11.19 years), and the UC group (n = 28) included 16 females and 12 males (average age = 36.9 ± 15.50 years). The control group (n = 50; healthy volunteers), included 36 females and 14 males (average age = 40.88 ± 9.11). The individuals from the control group did not manifest any signs or symptoms of inflammation (C-reactive protein, <5 mg/l; white blood cells, 4–10 × 103/µl). Additional exclusion criteria were autoimmune disorders, metabolic diseases or any chronic diseases in the past or at present. Disease activity score (UC: partial Mayo score; CD: Crohn’s disease activity index) was recorded for each patient. Demographic characteristics of patients with CD and UC is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of control participants and patients with UC and CD.

| Variable | CTR n = 50 | UC n = 28 | CD n = 27 | Statistical comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.58 ± 9.11 | 36.9 ± 15.50 | 34.7 ± 11.19 | s = 0.021

UC versus CTR s = 0.106 CD versus CTR s = 0.068 |

| Sex (male/female) | 14/36 | 12/16 | 14/13 | s = 0.0732 |

| Disease duration (years) | – | 4.96 ± 4.69 | 6.68 ± 4.8 | – |

| Disease phase (active/remission) | – | 18 active/10 remission | 19 active/8 remission | – |

Data are presented as mean values ±standard deviation.

Kruskal–Wallis H test for multiple comparison; bchi-squared test.

CD, Crohn’s disease; CTR, control; UC, ulcerative colitis.

The study was carried out with the consent of the patients, according to a protocol approved by the Local Bioethics Committee in Lublin (KE-0254/179/2016).

Genetic analyses

Blood was collected from the patients with IBD and controls between 7.00 and 11.00 a.m. mRNA transcript levels were assessed in isolated lymphocytes, by TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were compared with normal controls. Gene-specific probes (Hs00212039_m1 for AADAT, Hs00187858_m1 for CCBL1, Hs00219725_m1 for KAT3, and Hs99999905_m1 for GAPDH) were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Expression of the gene GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. The results were analysed using Expression Suite v. 1.0.3 software (Life Technologies). The gene expression value (RQ) of AADAT, CCBL1 and KAT3, relative to the control value, was calculated by the formula RQ = 2–ΔΔCt.21

Chromatographic analyses of TRP metabolites

Serum KYNA, KYN and TRP levels were determined by the ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) method with fluorescence detection (KYNA) and ultraviolet (UV) detection (KYN, TRP) using Waters Acquity UHPLC system and Waters C18 analytical column, according to Zhao and colleagues22 in modification. The mobile phase contained 20 mmol/l sodium acetate, 3 mmol/l zinc acetate and 7% acetonitrile, at a flow rate of 0.1 ml/min. Quantification of TRP and its metabolites was performed by a UV variable wavelength detector (KYN at 365 nm; TRP at 250 nm) and by a fluorescence detector (KYNA-344 nm excitation and 398 nm emission). The 3-OH-KYN levels were determined fluorometrically, using an electrochemical detector (potential of working electrode: +0.20 V; Coulochem III, ESA) as described before. The HPLC column (HR-80; 3 µm; C18 reverse-phase column; ESA) was perfused at 0.6 ml/min using a mobile phase consisting of 2% acetonitrile, 0.9% triethylamine, 0.59% phosphoric acid, 0.27 mM sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 8.9 mM heptane sulfonic acid.

Statistical analyses

The proportion of TRP to KYN, KYN to KYNA, KYN to 3-OH-KYN and KYNA to 3-OH-KYN was calculated for each sample and served for the further assessment of respective average ratios in the studied groups. Differences in the expression of genes, levels of serum TRP, KYN, KYNA, 3-OH-KYN and metabolites ratios between any two groups of the patients were evaluated by Mann–Whitney U test. Age and sex data were analysed by chi-squared and Kruskal–Wallis H tests. All of the analyses were performed with the use of the program, Statistica version 13.

Results

Genetic analyses

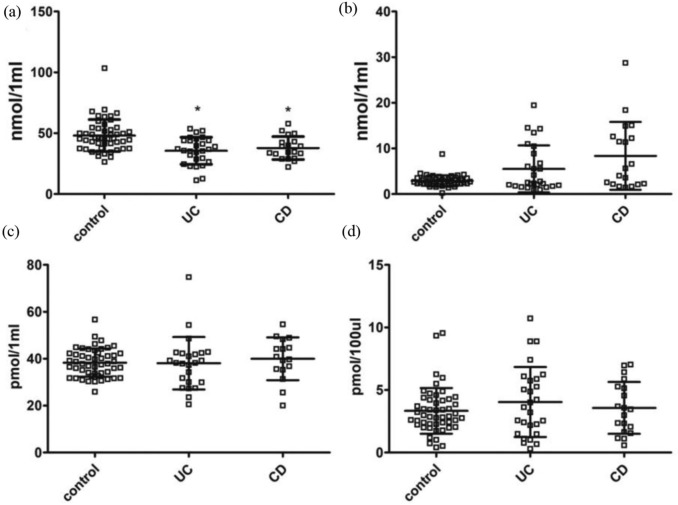

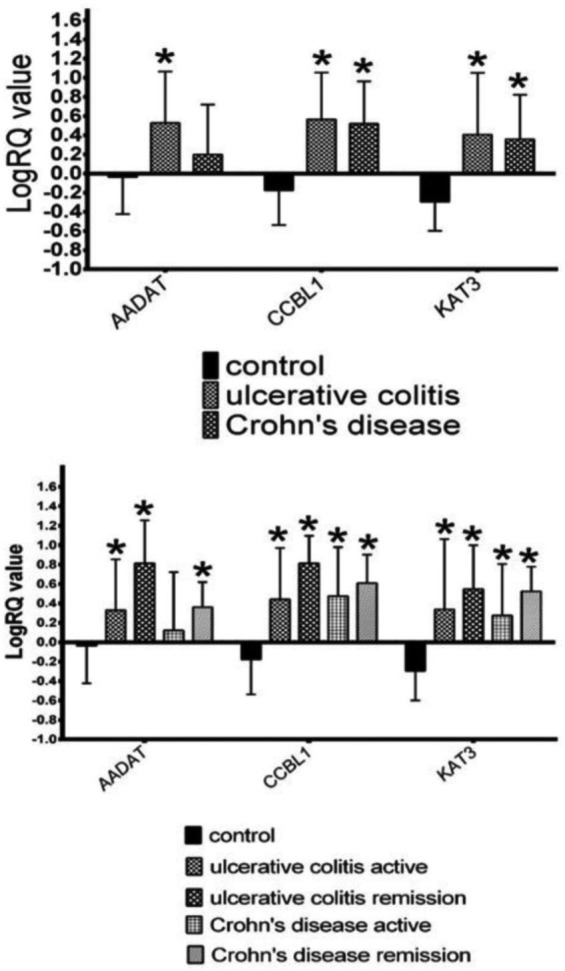

KAT1 and KAT3 mRNA expression was clearly enhanced in lymphocytes from both groups of patients with IBD, in comparison with controls [Figure 1(a); Table 2]. The expression was increased during the active phase of IBD as well as during remission [Figure 1(b); Table 3]. KAT2 expression was higher among patients with UC, but not in the entire CD group [Figure 1(a); Table 2]. When analysed in subsets, KAT2 expression was significantly increased in patients with CD with remission, but not during the active phase [Figure 1(b); Table 3].

Figure 1.

The expression of mRNA for KAT1 (CCBL1), KAT2 (AADAT) and KAT3 in entire cohorts of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (upper panel) and in relapse/remission (lower panel).

*p < 0.05 versus control, Mann–Whitney U test.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistic of gene expression values in the entire cohorts of patients with inflammatory bowel disease depicted in Figure 1 (upper panel).

| Gene | Group | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| logRQ AADAT | Control | −0.037417 | 0.386163 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | Control | −0.176893 | 0.361618 |

| logRQ KAT3 | Control | −0.295346 | 0.302771 |

| logRQ AADAT | UC | 0.529143 | 0.536293 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | UC | 0.565643 | 0.489776 |

| logRQ KAT3 | UC | 0.407314 | 0.644565 |

| logRQ AADAT | CD | 0.197536 | 0.522393 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | CD | 0.518931 | 0.444622 |

| logRQ KAT3 | CD | 0.358035 | 0.465991 |

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistic of gene expression values in subsets relapse/remission among UC and CD patients depicted in Figure 1 (lower panel).

| Gene | Group | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| logRQ AADAT | control | −0.037417 | 0.386163 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | control | −0.176893 | 0.361618 |

| logRQ KAT3 | control | −0.295346 | 0.302771 |

| logRQ AADAT | UC act | 0.329474 | 0.522930 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | UC act | 0.441619 | 0.530181 |

| logRQ KAT3 | UC act | 0.337341 | 0.725785 |

| logRQ AADAT | UC rem | 0.814384 | 0.442051 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | UC rem | 0.813690 | 0.283485 |

| logRQ KAT3 | UC rem | 0.547259 | 0.450270 |

| logRQ AADAT | CD act | 0.120905 | 0.600389 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | CD act | 0.474365 | 0.505363 |

| logRQ KAT3 | CD act | 0.275101 | 0.528823 |

| logRQ AADAT | CD rem | 0.360377 | 0.259126 |

| logRQ CCBL1 | CD rem | 0.608065 | 0.293896 |

| logRQ KAT3 | CD rem | 0.523903 | 0.255029 |

act, active; CD, Crohn’s disease; rem, remission; UC, ulcerative colitis.

TRP metabolites

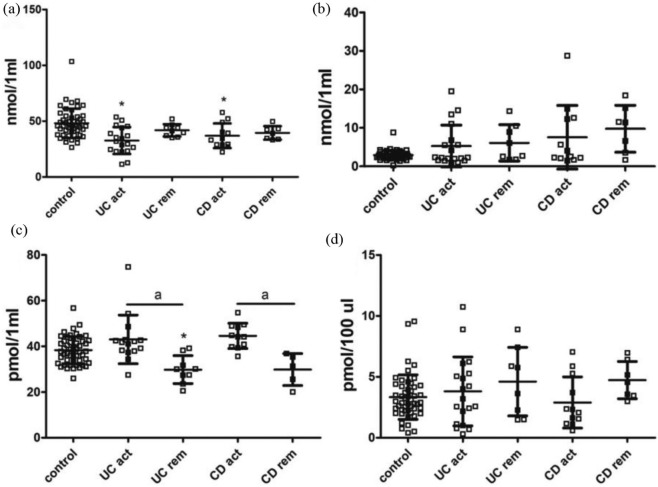

The analyses carried out in the entire groups of patients with UC and CD revealed a significant decrease in serum TRP level, but not in KYN, KYNA or 3-OH-KYN, in both forms of IBD in comparison with controls [Figure 2(a–d); Table 4]. Studies in subsets of patients with IBD showed that the lower TRP concentration was evident only among patients during active phase, but not in remission [Figure 3(a); Table 5]. There were no statistically significant differences in the levels of KYN and 3-OH-KYN between active/remission phases in both forms of IBD [Figure 3(b, d); Table 5]. In contrast, the KYNA level was lower during remission of UC or CD in comparison with respective relapse, but not versus controls [Figure 3(c); Table 5].

Figure 2.

Serum levels of TRP, KYN, KYNA and 3-OH-KYN in the entire cohorts of patients with UC or CD. (a) TRP, (b) KYN, (c) KYNA and (d) 3-OH-KYN.

Data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation.

*p < 0.05 versus control, Mann–Whitney U test.

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; CD, Crohn’s disease; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistic for examined variables in the entire cohorts of patients with inflammatory bowel disease depicted in Figure 2.

| Variable | Group | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| nmol TRP/1 ml | Control | 48.09521 | 13.11105 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | Control | 2.89472 | 1.20331 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | Control | 38.32564 | 6.01713 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN/100 µl | Control | 3.33292 | 1.82605 |

| nmol TRP/1 ml | UC | 35.57201 | 11.12452 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | UC | 5.50331 | 5.15197 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | UC | 38.07619 | 11.17509 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN/100 µl | UC | 4.03994 | 2.79404 |

| nmol TRP/1 ml | CD | 37.83329 | 9.397528 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | CD | 8.36110 | 7.433653 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | CD | 39.96442 | 9.110676 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN/100 µl | CD | 3.56931 | 2.073936 |

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; CD, Crohn’s disease; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Figure 3.

Serum levels of TRP, KYN, KYNA and 3-OH-KYN in active phase (act) versus remission (rem) subsets of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD). (a) TRP, (b) KYN, (c) KYNA and (d) 3-OH-KYN.

Data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation.

*p < 0.05 versus control, Mann–Whitney U test; ap < 0.05 versus respective remission.

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistic for examined variables in active phase (act) versus remission (rem) subsets of patients with UC or CD depicted in Figure 3.

| Variable | Group | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| nmol TRP/1 ml | Control | 48.09521 | 13.11105 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | Control | 2.89472 | 1.20331 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | Control | 38.32564 | 6.01713 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN/100 µl | Control | 3.33292 | 1.82605 |

| nmol TRP/1 ml | UC act | 32.63355 | 11.98789 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | UC act | 5.26213 | 5.42499 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | UC act | 43.03806 | 10.65319 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN/100 µl | UC act | 3.80238 | 2.83063 |

| nmol TRP/1 ml | UC rem | 41.77542 | 5.525099 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | UC rem | 6.07612 | 4.730355 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | UC rem | 29.80641 | 6.109712 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN/100 µl | UC rem | 4.60414 | 2.806357 |

| nmol TRP/1 ml | CD act | 36.89533 | 11.04814 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | CD act | 7.54809 | 8.26002 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | CD act | 44.56571 | 5.52225 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN /100 µl | CD act | 2.89248 | 2.09946 |

| nmol TRP/1 ml | CD rem | 39.44123 | 6.032050 |

| nmol KYN/1 ml | CD rem | 9.75484 | 6.091381 |

| pmol KYNA/1 ml | CD rem | 29.84158 | 6.979681 |

| pmol 3-OH-KYN /100 µl | CD rem | 4.72959 | 1.528392 |

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; CD, Crohn’s disease; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan; UC, ulcerative colitis.

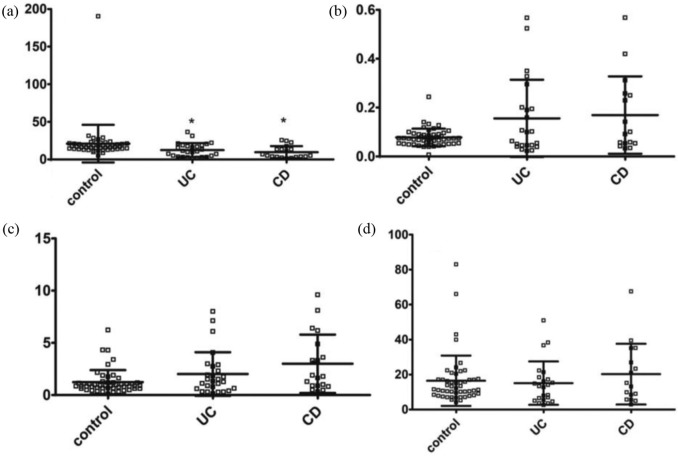

Functional changes in TRP metabolism

When analysed in the entire groups of patients with UC or CD, a significant decrease of TRP/KYN ratio was observed in comparison with controls [Figure 4(a); Table 6]. KYN/KYNA and KYNA/3-OH-KYN ratios were not altered in both forms of IBD [Figure 4(b, d); Table 6]. The ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN increased about two-fold among patients with CD [Figure 4(c); Table 6].

Figure 4.

The ratios between metabolites of TRP in the entire cohorts of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD). (a) TRP/KYN, (b) KYN/KYNA, (c) KYN/3-OH-KYN and (d) KYNA/3-OH-KYN.

Data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation.

*p < 0.05 versus control, Mann–Whitney U test.

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistic for examined variables in the entire cohorts of patients with inflammatory bowel disease depicted in Figure 4.

| Variable (ratio) | Group | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRP/KYN | Control | 20.97565 | 24.99752 |

| KYN/KYNA | Control | 0.07759 | 0.03575 |

| KYN/3-OH-KYN | Control | 1.23464 | 1.15304 |

| KYNA/3-OH-KYN | Control | 16.48301 | 14.37523 |

| TRP/KYN | UC | 12.40922 | 9.10632 |

| KYN/KYNA | UC | 0.15581 | 0.15807 |

| KYN/3-OH-KYN | UC | 2.01183 | 2.08659 |

| KYNA/3-OH-KYN | UC | 15.09839 | 12.37899 |

| TRP/KYN | CD | 12.40922 | 9.10632 |

| KYN/KYNA | CD | 0.16920 | 0.15836 |

| KYN/3-OH-KYN | CD | 2.99694 | 2.79473 |

| KYNA/3-OH-KYN | CD | 20.24263 | 17.36052 |

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; CD, Crohn’s disease; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan; UC, ulcerative colitis.

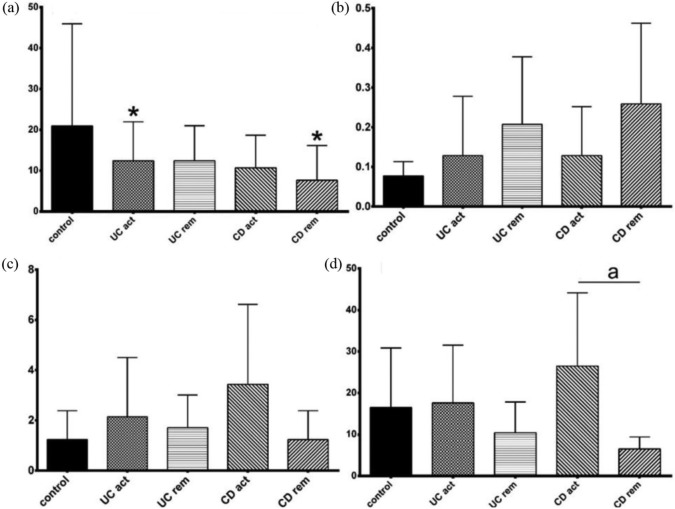

There was a decrease of TRP/KYN ratio in active phase of UC and among patients with CD in remission in comparison with control [Figure 5(a); Table 7]. No significant difference between relapse and remission for any of the analysed ratios, apart from an increase of KYNA/3-OH-KYN ratio in the active phase of CD in comparison with CD remission was observed [Figure 5(b–d); Table 7].

Figure 5.

The ratios between metabolites of TRP in active phase (act) versus remission (rem) subsets of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD). (a) TRP/KYN, (b) KYN/KYNA, (c) KYN/3-OH-KYN and (d) KYNA/3-OH-KYN.

Data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation.

*p < 0.05 versus control, ap < 0.05 versus respective remission; Mann–Whitney U test.

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistic for the examined variables in active phase (act) versus remission (rem) subsets of patients with UC or CD depicted in Figure 5.

| Variable | Group | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio TRP/KYN | Control | 20.97565 | 24.99752 |

| Ratio KYN/KYNA | Control | 0.07759 | 0.03575 |

| Ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN | Control | 1.23464 | 1.15304 |

| Ratio KYNA/3-OH-KYN | Control | 16.48301 | 14.37523 |

| Ratio TRP/KYN | UC act | 12.40523 | 9.55234 |

| Ratio KYN/KYNA | UC act | 0.12830 | 0.14983 |

| Ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN | UC act | 2.14093 | 2.35894 |

| Ratio KYNA/3-OH-KYN | UC act | 17.58799 | 13.93756 |

| Ratio TRP/KYN | UC rem | 12.41870 | 8.565722 |

| Ratio KYN/KYNA | UC rem | 0.20740 | 0.170197 |

| Ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN | UC rem | 1.70524 | 1.307593 |

| Ratio KYNA/3-OH-KYN | UC rem | 10.43040 | 7.410389 |

| Ratio TRP/KYN | CR act | 10.68468 | 7.98902 |

| Ratio KYN/KYNA | CR act | 0.12853 | 0.12342 |

| Ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN | CR act | 3.43799 | 3.18422 |

| Ratio KYNA/3-OH-KYN | CR act | 26.48682 | 17.64786 |

| Ratio TRP/KYN | CR rem | 7.651920 | 8.480039 |

| Ratio LKYN/KYNA | CR rem | 0.258654 | 0.203501 |

| Ratio KYN/3-OH-KYN | CR rem | 2.240854 | 1.945990 |

| Ratio KYNA/3-OH-KYN | CR rem | 6.505416 | 2.911304 |

3-OH-KYN, 3-hydroxykynurenine; CD, Crohn’s disease; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; TRP, tryptophan; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Discussion

In the population of patients with IBD, the expression of KAT1 and KAT3 mRNA in the lymphocytes was higher in comparison with healthy controls, and expression did not seem to be associated with the clinical phase of disease. Enhanced expression was noted in the entire cohorts of patients with UC and CD, as well as in the relapse/remission subsets. Expression of KAT2 mRNA was enhanced in the cohort of UC and in patients with CD during remission. Such upregulation of KYNA biosynthetic enzymes can be viewed either as a compensatory response to ongoing inflammation or a primary abnormality. Further analyses were aimed to establish whether enhanced expression of KATs mRNA was indeed followed by changes in TRP metabolites.

Concomitant evaluation of KYNA and related substances, that is, TRP itself, KYN, a direct KYNA precursor, and 3-OH-KYN, a second metabolite of KYN along another metabolic arm, revealed depletion of TRP but no change in other metabolites in the entire cohorts of UC and CD. This is in agreement with previous reports demonstrating a deficiency of TRP in IBD.18,19,23 We also observed significantly reduced TRP levels among both groups of patients with IBD during relapse, but not in remission.

The activity of rate-limiting enzyme, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), catabolizing TRP to KYN, is tightly regulated by proinflammatory molecules, and an enhanced expression of IDO in the intestinal mucosa of patients with IBD was shown previously.24,25 Thus, it is conceivable that the depletion of serum TRP results from an enhanced conversion to KYN. Indeed, we noted a significant decrease of the TRP/KYN ratio in patients with UC and CD, although serum KYN remained unchanged. A significant reduction in TRP availability combined with enhanced metabolic conversion of KYN to downstream products, may represent a possible explanation for this finding. Similarly, unchanged KYN levels were reported in patients with CD.18 However, others showed elevated serum KYN among patients with IBD.14,24 In our set of data, a trend for an increase in KYN was observed, but, due to a relatively low number of enrolled patients and high variability, the effect was not statistically significant.

Accumulating evidence indicates that availability of TRP plays a crucial role in the regulation of the immune response, notably as a counter-regulatory mechanism in inflammation.8 Mice fed a low-TRP diet were more susceptible to chemically induced inflammation, whereas a sufficient amount of TRP in the diet reduced inflammation and decreased the severity of colitis.25,26 Similarly, colitis symptoms and production of intestinal inflammatory cytokines in AhR-deficient mice were suppressed by activation of AhR with a TRP-enriched diet.27 Intensified conversion of TRP to KYNA along the KYN pathway has been implicated in the protective action of TRP in colitis. Such a scenario assumes that proinflammatory mediators produce a signal that simultaneously activates the mechanisms opposing inflammation. KYNA can mediate immunosuppressive effects, largely by targeting GPR35, abundantly expressed on enterocytes, or via AhR-associated signalling pathways.8 KYNA was also shown to inhibit tumour necrosis factor-α production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.28 Indeed, KYNA administration reduced colon motility and inflammation in an experimental model of colitis.16,17 Others, however, revealed that dietary TRP supplementation failed to improve the survival rate and to ameliorate the morphological parameters of experimental colitis in mice.29

Interestingly, despite uniformly enhanced expression of KATs, the average serum level of KYNA in the entire cohorts of patients with UC and CD was unchanged. However, when studied in subgroups of patients, KYNA was significantly lower during relapse in patients with UC in comparison with controls, similarly to data presented by others.19 Furthermore, in both, CD and UC subsets, KYNA was significantly lower during remission versus the respective active phase. There are two alternative explanations that may explain these observations. First, an increased expression of KATs may be either genetically determined or can reflect the activation of the KYN pathway by proinflammatory molecules released during an active systemic autoimmune process. It is conceivable that observed fluctuations in TRP and KYNA levels between relapse and remission in IBD mirror the existence of yet unidentified factor(s) directly regulating KYNA synthesis. Our reported decrease of serum KYNA during relapse in patients with UC and CD partially agrees with the data presented in an elegant study by Nikolaus and colleagues, concerning TRP and other kynurenines and performed on a large cohort of patients with IBD.19 A decrease in the serum KYNA level was observed among patients with CD but not those with UC in comparison with healthy controls.19 Ascribing this difference to the number of studied participants cannot be ruled out but this does not seem highly probable, considering that, similarly to others,19 we have found a decrease in TRP levels in patients with CD and UC, as well as lower TRP/KYN ratios. The nature of such a discrepancy is therefore, not clear and comparing the data on KATs mRNA expression could shed some light on this; however, to our knowledge, this issue has not been studied so far.

As mentioned above, our observation on decreased TRP levels in IBD is in agreement with other reports, performed in smaller and larger cohorts of patients and showing that depletion of TRP is linked with the relapse in IBD.6,19 Furthermore, the successful biological therapy evokes a sustained increase in TRP.19 It is tempting to explain our observation of enhanced KAT expression, as a regulatory, protective mechanism; the onset of acute inflammation resulting from exacerbation of IBD initiates a sequel of events starting from activation of IDO, followed by the immediate conversion of produced TRP to KYN, as well as activation of KATs, yet without a net increase of KYNA. Indeed, it was shown previously that, for example, the tumour necrosis factor-α-evoked stimulation of KAT expression is not paralleled by an increase in KYNA synthesis.30

Thus, permanently higher expression of KAT genes, together with a larger pool of KYNA substrate, KYN, would result in the functional boosting of the KYN pathway arm, leading to KYNA, and also in relatively weaker production of cytotoxic compounds along the other arm of the pathway. Indeed, we have observed an increase in the KYNA/3-OH-KYN ratio among a subset of patients with IBD during relapse. Prevailing KYNA could suppress cytotoxicity and inflammation and in this way restrict pathological events in IBD. This hypothesis requires further investigation and extended analyses are on the way. At present, we may only draw some conclusions based on scarce available literature, mostly concerning the effects of immune molecules on KAT expression in brain tissue.

In the rat brain, systemic lipopolysaccharide administration had no effect on KAT II expression.31 In macrophage and microglia cells, there was no effect of interferon-γ treatment on KAT activity.32 In human hippocampal progenitor cells, KAT I and KAT III, but not KAT II mRNA, were downregulated after interleukin-1β treatment.33 Importantly, in the course of another autoimmune disorder, multiple sclerosis, a significant decrease of KYNA in cerebrospinal fluid occurs during remission, whereas it is increased in the cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of patients with multiple sclerosis undergoing acute clinical exacerbation.34,35 It has been speculated that such changes in KYNA levels during disease progression and remission reflect a compensatory, protective mechanism against neurotoxicity. Thus, applying a similar pattern to IBD, one may hypothesize that during relapse, relatively stronger activity of the KYN pathway arm leading to KYNA is aimed to counteract inflammation and cytotoxicity. The nature of mechanisms underlying such regulation remains to be established and seems of great interest.

An alternative explanation arises from recent data implicating the composition of intestinal microbiota as the factor altering the host immune system and influencing TRP availability and metabolism.23 The interactions are reciprocal and TRP and its metabolites of (1) alimentary origin, (2) produced by gut microbiota (indole, indolic acid, skatole, and tryptamine), and (3) endogenously synthesized (kynurenines, serotonin, and melatonin), may impact the microbial composition and the host–microbiome interaction.26 Considering that enhanced expression of KATs was found in patients with IBD irrespective of disease activity, the dysbiotic microbiome could produce larger quantities of TRP, subsequently converted to KYN, during relapse. In fact, interleukin-10-deficient (IL-10−/−) mice, developing CD-like colitis when exposed to a pathogenic microbial environment, manifested elevated plasma KYN.36 Conversely, restoration of intestinal levels of probiotic bacteria such as Lactobacillus sp., evoked a decrease in serum KYN in stressed mice.37 Taken together, the data presented here support and extend previous findings on altered TRP metabolism in IBD.

Conclusion

The presented data indicate that IBD is associated with an enhanced expression of genes encoding KYNA biosynthetic enzymes in lymphocytes; however, additional mechanisms appear to influence KYNA levels. Higher metabolic conversion of serum TRP in IBD seems to be followed by the functional shift of KYN pathway towards the arm producing KYNA during exacerbation. We propose that KYNA, possibly via interaction with the AhR or GPR35, may serve as a counter-regulatory mechanism, decreasing cytotoxicity and inflammation in IBD. Further longitudinal studies evaluating the individual dynamics of TRP and the KYN pathway in patients with IBD, as well as the nature of precise mechanisms regulating KYNA synthesis, should be helpful in better understanding the processes underlying observed changes.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by grants from Medical University in Lublin, Poland (grant numbers DS 450/16, DS 450/17, and DS 450/18).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability: The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

ORCID iD: Ewa Dudzińska  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3077-4288

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3077-4288

Contributor Information

Ewa Dudzińska, Medical University of Lublin, Chodźki 1 Street, Lublin, 20-093, Lubelskie, Poland.

Kinga Szymona, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Renata Kloc, Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Paulina Gil-Kulik, Department of Clinical Genetics, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Tomasz Kocki, Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Małgorzata Świstowska, Department of Clinical Genetics, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Jacek Bogucki, Department of Clinical Genetics, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Janusz Kocki, Department of Clinical Genetics, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland.

Ewa M. Urbanska, Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Lubelskie, Poland

References

- 1. Schoultz I, Keita ÅV. Cellular and molecular therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease-focusing on intestinal barrier function. Cells 2019; 22: E193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freeman HJ. Natural history and long-term clinical course of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 7: 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manuc TE, Manuc MM, Diculescu MM. Recent insights into the molecular pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease: a review of emerging therapeutic targets. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2016; 15: 59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 7: 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Etienne-Mesmin L, Chassaing B, Gewirtz AT. Tryptophan: gut microbiota-derived metabolites regulating inflammation. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2017; 6: 7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ye BD, McGovern DP. Genetic variation in IBD: progress, clues to pathogenesis and possible clinical utility. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2016; 12: 1091–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dudzińska E, Gryzinska M, Kocki J. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in selected genes in inflammatory bowel disease. Biomed Res Int 2018; 2018: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wirthgen E, Hoeflich A, Rebl A, et al. Kynurenic acid: the Janus-faced role of an immunomodulatory tryptophan metabolite and its link to pathological conditions. Front Immunol 2018; 10: 1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Urbańska EM, Chmiel-Perzyńska I, Perzyński A, et al. Endogenous kynurenic acid and neurotoxicity. In: Kostrzewa R. (eds) Handbook of neurotoxicity. New York, NY: Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramos-Chávez LA, Lugo Huitrón R, González Esquivel D, et al. Relevance of alternative routes of kynurenic acid production in the brain. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018; 24: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han Q, Cai T, Tagle DA, et al. Structure, expression, and function of kynurenine aminotransferases in human and rodent brains. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010; 67: 353–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stazka J, Luchowski P, Wielosz M, et al. Endothelium-dependent production and liberation of kynurenic acid by rat aortic rings exposed to L-kynurenine. Eur J Pharmacol 2002; 19: 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walczak K, Dabrowski W, Langner E, et al. Kynurenic acid synthesis and kynurenine aminotransferases expression in colon derived normal and cancer cells. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forrest CM, Gould SR, Darlington LG, et al. Levels of purine, kynurenine and lipid peroxidation products in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2003; 527: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turski MP, Turska M, Paluszkiewicz P, et al. Kynurenic Acid in the digestive system-new facts, new challenges. Int J Tryptophan Res 2013; 4: 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaszaki J, Palásthy Z, Erczes D, et al. Kynurenic acid inhibits intestinal hypermotility and xanthine oxidase activity during experimental colon obstruction in dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008; 20: 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Érces D, Varga G, Fazekas B, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist therapy suppresses colon motility and inflammatory activation six days after the onset of experimental colitis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2012; 15: 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta NK, Thaker AI, Kanuri N, et al. Serum analysis of tryptophan catabolism pathway: correlation with Crohn’s disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1214–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nikolaus S, Schulte B, Al-Massad N, et al. Increased tryptophan metabolism is associated with activity of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2017; 153: 1504–1516.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015; 21: 1982–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 2011; 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao J, Gao P, Zhu D. Optimization of Zn2+-containing mobile phase for simultaneous determination of kynurenine, kynurenic acid and tryptophan in human plasma by high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2010; 15: 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sofia MA, Ciorba MA, Meckel K, et al. Tryptophan metabolism through the kynurenine pathway is associated with endoscopic inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018; 8: 1471–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolf AM, Wolf D, Rumpold H, et al. Overexpression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou L, Chen H, Wen Q, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in human inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 24: 695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gao J, Xu K, Liu H, et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on intestinal immunity mediated by tryptophan metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018; 6: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Y, Wang X, Hu CA. Therapeutic potential of amino acids in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients 2017; 23: pii: E920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tiszlavicz Z, Németh B, Fülöp F, et al. Different inhibitory effects of kynurenic acid and a novel kynurenic acid analogue on tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production by mononuclear cells, HMGB1 production by monocytes and HNP1-3 secretion by neutrophils. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2011; 383: 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen S, Wang M, Yin L, et al. Effects of dietary tryptophan supplementation in the acetic acid-induced colitis mouse model. Food Funct 2018; 15: 4143–4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Asp L, Johansson AS, Mann A, et al. Effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines on expression of kynurenine pathway enzymes in human dermal fibroblasts. J Inflamm 2011; 8: 8: 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Connor TJ, Starr N, O’sullivan JB, et al. Induction of indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase and kynurenine 3-monooxygenase in rat brain following a systemic inflammatory challenge: a role for IFN-gamma? Neurosci Lett 2008; 441: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alberati-Giani D, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Kohler C, et al. Regulation of the kynurenine metabolic pathway by interferon-gamma in murine cloned macrophages and microglial cells. J Neurochem 1996; 66: 996–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, et al. Interleukin-1beta: a new regulator of the kynurenine pathway affecting human hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012; 37: 939–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rejdak K, Bartosik-Psujek H, Dobosz B, et al. Decreased level of kynurenic acid in cerebrospinal fluid of relapsing-onset multiple sclerosis patients. Neurosci Lett 2002; 331: 63–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rejdak K, Petzold A, Kocki T, et al. Astrocytic activation in relation to inflammatory markers during clinical exacerbation of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neural Transm 2007; 114: 1011–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin HM, Barnett MP, Roy NC, et al. Metabolomic analysis identifies inflammatory and noninflammatory metabolic effects of genetic modification in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease. J Proteome Res 2010; 5: 1965–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marin IA, Goertz JE, Ren T, et al. Microbiota alteration is associated with the development of stress-induced despair behavior. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 43859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]