This study uses survey data to examine the racial/ethnic disparities in breastfeeding trends in the United States.

Key Points

Question

What are the racial/ethnic disparities in breastfeeding trends?

Findings

In this study of data from the National Immunization Survey–Child, breastfeeding rates were increased in each racial/ethnic group from 2009 to 2015. Non-Hispanic black infants continued to have lower breastfeeding rates than white infants, whereas the gaps between white infants and most other nonwhite infants were smaller in association with greater increases among white infants.

Meaning

More efforts appear to be needed to improve breastfeeding rates among black infants.

Abstract

Importance

Large racial/ethnic disparities in breastfeeding are associated with adverse health outcomes.

Objectives

To examine breastfeeding trends by race/ethnicity from 2009 to 2015 and changes in breastfeeding gaps comparing racial/ethnic subgroups with white infants from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study used data from 167 842 infants from the National Immunization Survey–Child (NIS-Child), a random-digit–dialed telephone survey among a complex, stratified, multistage probability sample of US households with children aged 19 to 35 months at the time of the survey. This study analyzed data collected from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2017, for children born between 2009 and 2015.

Exposures

Child’s race/ethnicity categorized as Hispanic or non-Hispanic white, black, Asian, or American Indian or Alaskan Native.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Breastfeeding rates, including ever breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months, and continuation of breastfeeding at 12 months.

Results

This study included 167 842 infants (mean [SD] age, 2.33 [0.45] years; 86 321 [51.4%] male and 81 521 [48.6%] female). Overall unadjusted breastfeeding rates increased from 2009 to 2015 by 7.1 percentage points for initiation, 9.2 percentage points for exclusivity, and 11.3 percentage points for duration, with considerable variation by race/ethnicity. Most racial/ethnic groups had significant increases in breastfeeding rates. From 2009-2010 to 2014-2015, disparities in adjusted breastfeeding rates became larger between black and white infants. For example, the difference for exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months between black and white infants widened from 0.5 to 4.5 percentage points with a 4.0% difference in difference (P < .001) from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015. In contrast, the breastfeeding differences between Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian or Alaskan Native infants and white infants became smaller or stayed the same except for continued breastfeeding at 12 months among Asians. For example, the difference in continued breastfeeding at 12 months between Hispanic and white infants decreased from 7.8 to 3.8 percentage points between 2 periods, yielding a −4.0% difference in difference (P < .001). Because of positive trends among all race/ethnicities, these reduced differences were likely associated with greater increases among white infants throughout the study years.

Conclusions and Relevance

Despite breastfeeding improvements among each race/ethnicity group, breastfeeding disparities between black and white infants became larger when breastfeeding improvements decreased even further among black infants in 2014-2015. The reduced breastfeeding gaps among all other nonwhite groups may be associated with greater increases among white infants. More efforts appear to be needed to improve breastfeeding rates among black infants.

Introduction

Breastfeeding is the optimal feeding method for infant nutrition and growth. It is associated with a reduced risk of many children’s illnesses, such as otitis media, gastrointestinal tract infections, respiratory tract infections, sudden infant death syndrome, and childhood obesity.1 Mothers who breastfeed have a reduced risk of breast and ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension.2 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants be fed only human milk for approximately the first 6 months of life, with continued breastfeeding along with complementary foods for at least 1 year.3

There are large breastfeeding disparities by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics, and geography.4,5 A previous study,6 using data from the National Immunization Survey–Child (NIS-Child), an ongoing national survey among US households with young children, found that the gap in ever breastfeeding between black and white infants narrowed by 8.1 percentage points among children born in 2008 compared with children born in 2000, but the gap in breastfeeding continuation at 12 months widened by 1 percentage point. Hispanic infants had breastfeeding rates similar to or slightly higher than among white infants during the study period. Breastfeeding disparities are associated with substantial differences in health outcomes for both mothers and children. For example, compared with white infants, black infants are estimated to have 1.7 times excess cases of acute otitis media, 3.3 times excess cases of necrotizing enterocolitis, and 2.2 times excess child deaths associated with suboptimal breastfeeding.7

Monitoring breastfeeding progress and identifying disparities are crucial for designing and implementing targeted interventions. The NIS-Child is the primary data source for US breastfeeding surveillance and the establishment of Healthy People 2020 objectives, with a target of 81.9% for breastfeeding initiation, 25.5% for exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months, and 34.1% for continuation at 12 months by 2020.8 As a continuation and expansion of previous analyses, this study examined breastfeeding trends and disparities by race/ethnicity using NIS-Child data from children born from 2009 to 2015.

Methods

Study Sample

This study used data from the NIS-Child, a national, ongoing, random-digit–dialed telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to estimate vaccination coverage and breastfeeding rates among US children.9 The survey was designed as a complex, stratified, multistage probability sample of US households with children aged 19 to 35 months. Interviews were conducted with the parent or guardian, with all data weighted to adjust for the selection probability, multiple telephone lines, mixed telephone use (landline and cellular), household nonresponse, and the exclusion of phoneless households. This analysis includes data collected from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2017. The Council of American Survey and Research Organizations’ response rates of 2011-2017 NIS-Child ranged from 55.7% to 62.6% for the landline samples and 32.1% to 33.5% for the cellular telephone samples. The NIS-Child was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics’ Research Ethics Review Board. The authority under which these data are collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is given in §308(d) of the Public Health Service Act, 42 USC §242m(d) and the Privacy Act of 1974, 5 USC §552a. Patient consent is provided orally from the person in the household who is most knowledgeable about the eligible child's vaccination history. The data used for this analysis are deidentified. The National Center for Health Statistics' Research Ethics Review Board has reviewed and approved this analysis.

Breastfeeding Outcome Measures

Because children are aged 19 to 35 months at the interview, each annual NIS-Child survey includes children born in 3 calendar years. We conducted analyses by birth year from January 1, 2009, through December 31, 2015, with each birth cohort including all 3 survey years’ data with the exception of the 2009 and 2015 birth cohorts. For the 2009 birth cohort, only the last 2 survey years of data (2011 and 2012) were used because the cellular telephone sample was not added until 2011. For the 2015 birth cohort, the first 2 survey years of data (2016 and 2017) were used because the third year of data from the 2018 NIS-Child was not available at the time of this analysis. A previous analysis10 found that adding a third year of data to the birth cohort did not alter the point estimates and only reduced the width of the CIs by approximately 20%.

This study examined 3 breastfeeding rates: (1) ever breastfeeding by asking, “Was [child’s name] ever breastfed or fed breast milk?”; (2) exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months by asking, “How old was [child’s name] when he/she was first fed formula?” and “How old was [child's name] when (he/she) was first fed anything other than breast milk or formula? (including juice, cow's milk, sugar water, baby food, or anything else that [child’s name] may have been given, even water)”; and (3) continuation of breastfeeding at 12 months by asking, “How old was [child’s name] when [child’s name] completely stopped breastfeeding or being fed breast milk?”

Independent Measures

A single, mutually exclusive race/ethnicity variable was created based on responses to questions about the child’s race(s) and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity to categorize infants as Hispanic or non-Hispanic of white, black, Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 2 or more races. Given the small sample size for Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders and unspecified origins in the 2 or more race/ethnicity category, these 2 groups are not presented separately in the results but included in the total estimates.

Covariates included infant sex; birth order (first born or not); participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); maternal marital status (married or not); maternal educational level (less than high school, high school graduate, some college or technical school, or college graduate or higher); and household poverty level calculated according to US Census poverty thresholds and categorized into less than 100%, 100% to 199%, 200% to 399%, 400% to 599%, or 600% or higher than the poverty guideline. Using 185% of the poverty guideline as the cutoff, children who never received WIC benefits were further categorized into eligible or ineligible.

Statistical Analysis

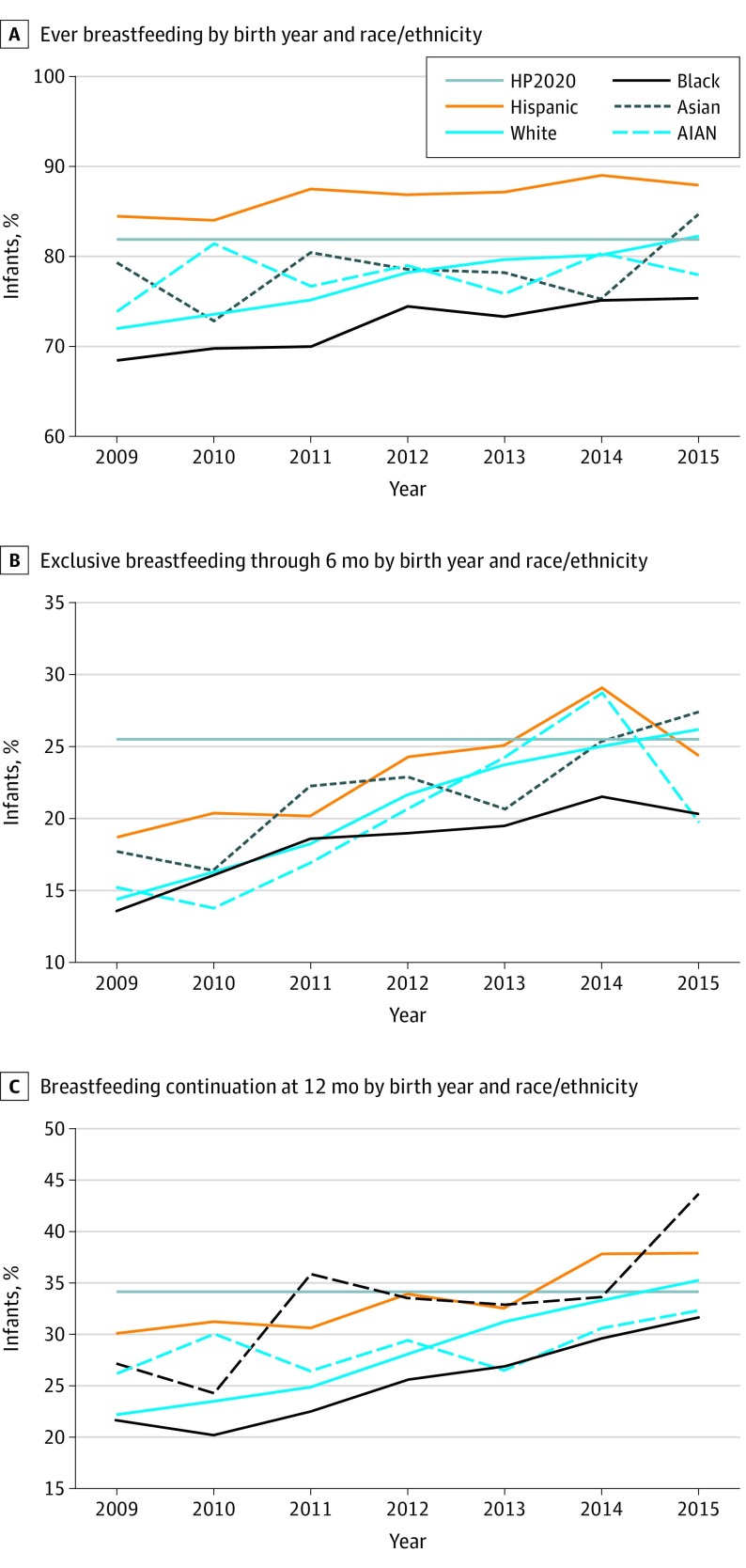

Crude breastfeeding rates were tabulated by birth year for each race/ethnicity from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2015 (Table 1). The slope of breastfeeding trends was examined by regressing rates on years, and the significance of each trend was tested by relating each breastfeeding measurement to the time when it occurred in the regression modeling.11 The changes in population distribution across years were examined using simple logistic regression, with each binary independent variable regressed on birth year (eTable in the Supplement). For independent variables with more than 2 categories, we created a binary variable for each category, such as Hispanic vs everyone else and black vs everyone else. To illustrate the breastfeeding trends after taking the differences in demographic distribution into consideration, adjusted breastfeeding rates were also calculated for each race/ethnicity after controlling for infant sex, birth order, WIC participation, marital status, maternal educational level, and household income (Figure 1).

Table 1. Crude Breastfeeding Rates Among 167 842 Children Born From 2009 to 2015a.

| Variable | Year of Birth, % (SE) | Slopeb | P Value for Trendb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||

| Ever breastfeeding | |||||||||

| Total | 76.1 (0.50) | 77.0 (0.51) | 78.8 (0.50) | 80.5 (0.48) | 81.1 (0.44) | 82.2 (0.44) | 83.2 (0.53) | 1.22 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 80.1 (1.07) | 79.1 (1.20) | 83.1 (1.05) | 82.9 (1.07) | 82.9 (1.01) | 85.3 (0.93) | 84.6 (1.21) | 0.92 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 77.7 (0.62) | 79.0 (0.59) | 80.7 (0.59) | 83.2 (0.51) | 84.4 (0.49) | 85.0 (0.50) | 85.9 (0.60) | 1.43 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 60.7 (1.56) | 62.3 (1.55) | 62.4 (1.68) | 67.0 (1.49) | 66.3 (1.44) | 68.1 (1.44) | 69.4 (1.80) | 1.49 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 86.3 (1.91) | 82.9 (2.67) | 86.9 (2.18) | 83.7 (2.73) | 84.2 (1.84) | 81.4 (2.92) | 89.3 (1.79) | 0.12 | .77 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native | 69.1 (5.44) | 75.4 (4.01) | 72.7 (4.13) | 74.5 (4.13) | 69.5 (3.99) | 76.1 (3.18) | 76.4 (5.78) | 0.71 | .46 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding through 6 mo | |||||||||

| Total | 15.7 (0.45) | 17.4 (0.48) | 19.0 (0.49) | 22.3 (0.53) | 23.3 (0.49) | 25.7 (0.53) | 24.9 (0.60) | 1.74 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 15.5 (1.09) | 17.0 (1.21) | 16.8 (1.18) | 20.1 (1.24) | 20.8 (1.21) | 25.2 (1.36) | 20.9 (1.32) | 1.31 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 16.6 (0.51) | 18.7 (0.56) | 20.9 (0.58) | 25.2 (0.68) | 27.4 (0.62) | 28.1 (0.61) | 29.5 (0.80) | 2.29 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 10.7 (1.08) | 12.6 (1.22) | 14.8 (1.34) | 14.3 (1.17) | 15.4 (1.11) | 17.4 (1.22) | 17.2 (1.57) | 1.05 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 22.0 (3.05) | 20.7 (2.68) | 26.7 (2.80) | 26.8 (2.70) | 24.4 (2.41) | 28.9 (2.52) | 30.1 (2.97) | 1.38 | .02 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native | 13.4 (2.90) | 11.2 (2.56) | 16.2 (3.13) | 17.3 (3.53) | 20.4 (3.20) | 25.5 (4.06) | 19.6 (3.66) | 1.84 | .003 |

| Breastfeeding continuation at 12 mo | |||||||||

| Total | 24.6 (0.51) | 25.3 (0.55) | 26.8 (0.55) | 29.5 (0.56) | 31.3 (0.52) | 34.1 (0.55) | 35.9 (0.67) | 2.00 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 26.1 (1.23) | 26.5 (1.40) | 25.2 (1.36) | 27.9 (1.36) | 26.7 (1.19) | 32.3 (1.37) | 32.6 (1.57) | 1.17 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 25.7 (0.60) | 27.2 (0.63) | 28.7 (0.64) | 33.1 (0.72) | 36.1 (0.66) | 37.9 (0.65) | 39.8 (0.83) | 2.54 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 15.9 (1.23) | 14.4 (1.23) | 17.3 (1.37) | 18.3 (1.29) | 20.2 (1.17) | 23.1 (1.31) | 24.0 (1.61) | 1.59 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 34.9 (2.87) | 33.0 (2.88) | 43.9 (3.12) | 39.5 (2.77) | 40.9 (2.40) | 40.1 (2.55) | 50.3 (3.46) | 2.06 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native | 22.8 (5.96) | 23.7 (6.93) | 22.7 (3.66) | 25.3 (4.28) | 21.7 (3.01) | 27.3 (3.93) | 31.3 (5.48) | 1.13 | .29 |

Each birth cohort includes data from 3 survey years except for 2009 and 2015 births, when only 2 survey years of data were available.

Slope and P values for trend were obtained by unadjusted linear regression models, with P < .05 indicating a significant trend.

Figure 1. Adjusted Breastfeeding Rates by Birth Year and Race/Ethnicity Among Children Born From 2009 to 2015 .

Rates were adjusted for infant sex; birth order; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participation; marital status; maternal educational level; and household income. AIAN indicates American Indian or Alaskan Native; HP2020, Healthy People 2020.

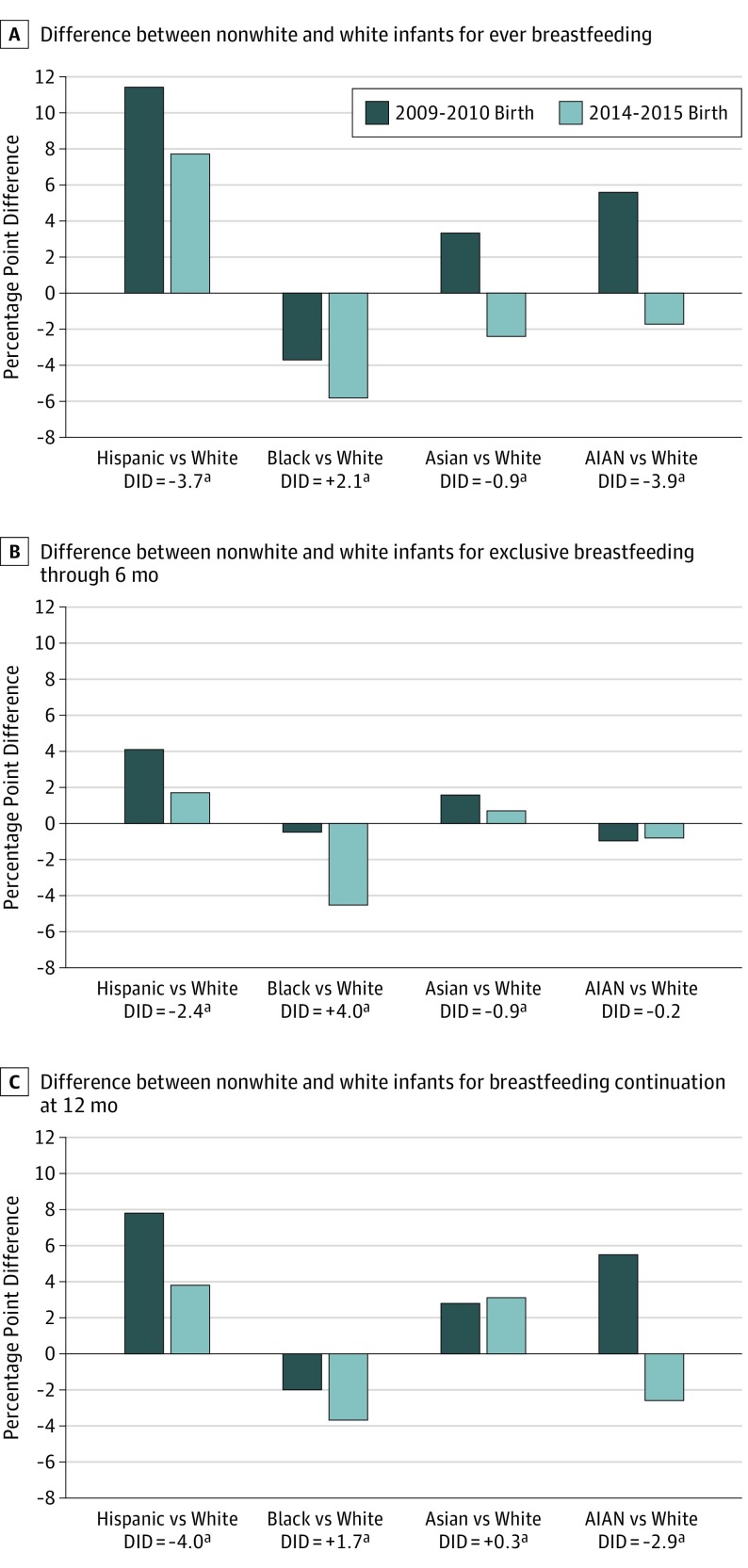

For comparisons between the beginning and end of the study period, we combined the first and last 2 birth cohorts into one time point to increase sample size. Both crude and adjusted breastfeeding rates were calculated; Pearson χ2 tests were conducted to estimate the significance of absolute differences within the same time points and between 2 different time points for each race/ethnicity (Table 2). We also applied the difference in difference (DID) method to examine the changes in breastfeeding gaps throughout the study years by subtracting the differences between nonwhite and white infants in 2009-2010 from those in 2014-2015.12 The direction and change of racial/ethnic gaps based on adjusted rates are shown in Figure 2. To identify the independent associations of race/ethnicity with DID after accounting for sociodemographic status, generalized linear models with nonidentity link were used to test the significance of interactions of estimated values between race and years. Adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% CIs were calculated using estimated marginal values in the multiple logistic regression analysis after controlling for all the confounding factors (Figure 3). To account for the cluster sampling design, we used Taylor series linearization for variance estimation using SUDAAN, version 11 (RTI International). Survey design variables and sample weights accounting for differential probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and noncoverage were used to obtain estimates representative of young children in the United States. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Table 2. Comparison of Crude and Adjusted Breastfeeding Rates by Race/Ethnicity.

| Variable | 2009-2010 Birth (n = 47 696) | 2014-2015 Birth (n = 45 221) | Difference From 2009-2010 to 2014-2015b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate, % (SE) | Absolute Racial Differences in Adjusted Ratesb | Rate, % (SE) | Absolute Racial Differences in Adjusted Ratesb | Crude Rates | Adjusted Rates | |||

| Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | |||||

| Ever breastfeeding | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 79.6 (0.81) | 84.2 (0.66) | 11.4c | 85.0 (0.75) | 88.7 (0.60) | 7.7c | 5.4c | 4.5c |

| Non-Hispanic white | 78.4 (0.43) | 72.8 (0.55) | 1 [Reference] | 85.3 (0.39) | 81.0 (0.52) | 1 [Reference] | 6.9c | 8.2c |

| Non-Hispanic black | 61.5 (1.10) | 69.1 (0.96) | −3.7c | 68.7 (1.13) | 75.2 (0.95) | −5.8c | 7.2c | 6.1c |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 84.5 (1.67) | 76.1 (2.08) | 3.3c | 84.2 (2.04) | 78.6 (2.30) | −2.4c | −0.3 | 2.5 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native | 72.7 (3.38) | 78.4 (2.99) | 5.6c | 76.2 (3.16) | 79.3 (3.17) | −1.7 | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding through 6 mo | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 16.2 (0.82) | 19.5 (0.93) | 4.1c | 23.5 (0.98) | 27.2 (1.05) | 1.7c | 7.3c | 7.7c |

| Non-Hispanic white | 17.7 (0.38) | 15.4 (0.37) | 1 [Reference] | 28.7 (0.48) | 25.5 (0.48) | 1 [Reference] | 11.0c | 10.1c |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11.7 (0.82) | 14.9 (1.03) | −0.5 | 17.3 (0.97) | 21.0 (1.07) | −4.5c | 5.6c | 6.1c |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 21.3 (2.03) | 17.0 (1.76) | 1.6 | 29.4 (1.93) | 26.2 (1.81) | 0.7 | 8.1c | 9.2c |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native | 12.1 (1.94) | 14.4 (2.24) | −1.0 | 23.0 (2.89) | 24.7 (3.15) | −0.8 | 10.9c | 10.3c |

| Breastfeeding continuation at 12 mo | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 26.3 (0.95) | 30.7 (1.01) | 7.8c | 32.4 (1.04) | 37.8 (1.08) | 3.8c | 6.1c | 7.1c |

| Non-Hispanic white | 26.4 (0.43) | 22.9 (0.42) | 1 [Reference] | 38.7 (0.52) | 34.0 (0.51) | 1 [Reference] | 12.3c | 11.1c |

| Non-Hispanic black | 15.2 (0.87) | 20.9 (1.11) | −2.0c | 23.5 (1.02) | 30.3 (1.17) | −3.7c | 8.3c | 9.4c |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 33.9 (2.04) | 25.7 (1.74) | 2.8c | 43.7 (2.12) | 37.1 (1.94) | 3.1c | 9.8c | 11.4c |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native | 23.3 (4.71) | 28.4 (5.53) | 5.5c | 29.0 (3.27) | 31.4 (3.62) | −2.6 | 5.7 | 3.0 |

Adjusted rates were obtained by the predicted values from multiple logistic regressions controlling for infant sex, birth order, Women, Infants, and Children participation, marital status, maternal education, and household income.

Absolute differences within each birth cohort and between 2009-2010 and 2014-2015 for each race/ethnicity.

P < .05 for the statistically significant absolute differences.

Figure 2. Racial/Ethnic Differences on Adjusted Breastfeeding Rates .

Rates were adjusted for infant sex; birth order; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participation; marital status; maternal educational level; and household income. AIAN indicates American Indian or Alaskan Native; DID, difference in difference.

aP < .05.

Figure 3. Adjusted Prevalence Ratios (APRs) for Breastfeeding Among Children Born in 2009-2010 or 2014-2015 .

Rates were adjusted for infant sex; birth order; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participation; marital status; maternal educational level; and household income (reference was white infants). AIAN indicates American Indian or Alaskan Native. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Results

This study included 167 842 infants (mean [SD] age, 2.33 [0.45] years; 86 321 [51.4%] male and 81 521 [48.6%] female) across 7 birth years (see sample size and characteristics in eTable in the Supplement). From 2009 to 2015, there were significant overall increases in crude breastfeeding rates, with ever breastfeeding increasing by 7.1 percentage points (76.1% to 83.2%), exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months by 9.2 percentage points (15.7% to 24.9%), and breastfeeding continuation at 12 months by 11.3 percentage points (24.6% to 35.9%) (Table 1). White infants had the largest slopes in exclusivity (slope, 2.29; P < .001) and continuation of breastfeeding (slope, 2.54; P < .001), indicating the fastest growth on these 2 measures. Breastfeeding improvements were observed among each race/ethnicity except for ever breastfeeding among Asian (slope, 0.12; P = .77) and American Indian or Alaskan Native infants (slope, 0.71; P = .46) and breastfeeding continuation at 12 months among American Indian or Alaskan Native infants (slope, 1.13; P = .29). Only Asian and white infants attained all 3 Healthy People 2020 breastfeeding targets, but black infants continuously had the lowest breastfeeding rates even after controlling for sociodemographic factors (Figure 1).

Table 2 indicates that adjusted breastfeeding rates were lower than the corresponding crude rates among white (eg, 72.8% vs 78.4% for initiation, 15.4% vs 17.7% for exclusivity, and 22.9% vs 26.4% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010) and Asian (eg, 76.1% vs 84.5% for initiation, 17.0% vs 21.3% for exclusivity, and 25.7% vs 33.9% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010) infants but higher among Hispanic (eg, 84.2% vs 79.6% for initiation, 19.5% vs 16.2% for exclusivity, and 30.7% vs 26.3% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010), black (eg, 69.1% vs 61.5% for initiation, 14.9% vs 11.7% for exclusivity, and 20.9% vs 15.2% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010), and American Indian or Alaskan Native (eg, 78.4% vs 72.7% for initiation, 14.4% vs 12.1% for exclusivity, and 28.4% vs 23.3% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010) infants. Figure 2 shows that from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015, breastfeeding disparities in all 3 adjusted rates became larger between black and white infants as disparities further increased in black infants in 2014-2015. For example, the difference on exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months between black and white infants widened from 0.5 to 4.5 percentage points, yielding a 4.0% DID (P < .001) throughout the study years. In contrast, the breastfeeding gaps between Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian or Alaskan Native infants compared with white infants became smaller from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 except for continued breastfeeding at 12 months among Asian infants. For example, the difference in continued breastfeeding at 12 months between Hispanic and white infants decreased from 7.8 to 3.8 percentage points throughout the years, yielding a −4.0% DID (P < .001). Given the large variation within and across birth years for different racial/ethnic groups, the following results are presented separately for each racial/ethnic group using white infants as the reference.

Hispanic Infants

Crude breastfeeding rates among Hispanic infants were lower or comparable to those among white infants (eg, 79.6% vs 78.4% for initiation, 16.2% vs 17.7% for exclusivity, and 26.3% vs 26.4% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010), but the adjusted rates were higher among Hispanic infants than those among white infants after controlling for sociodemographic factors (eg, in 2009-2010, breastfeeding rates among Hispanic infants were 11.4 percentage points higher for initiation, 4.1 percentage points higher for exclusivity, and 7.8 percentage points higher for duration of breastfeeding compared with white infants) (Table 2 and Figure 3). Although adjusted rates increased from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 among both white and Hispanic infants, the gaps between Hispanic and white infants decreased throughout the study years as Hispanic infants had smaller percentage-point increases compared with white infants (Figure 2). For example, white infants had a larger increase from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 in adjusted ever breastfeeding rates than Hispanic infants (8.2 vs 4.5 percentage points) (Table 2). Thus, even though Hispanic infants had a persistently higher rate than white infants, the gap in ever breastfeeding decreased from 11.4 percentage points in 2009-2010 to 7.7 percentage points in 2014-2015, resulting in a significantly narrowed gap indicated by −3.7% DID (P < .001) (Figure 2).

Non-Hispanic Black Infants

Black infants had smaller percentage-point increases than white infants despite breastfeeding improvements in the group (ie, compared with the 8.2 percentage-point increase for initiation, 10.1 percentage-point increase for exclusivity, and 11.1 percentage-point increase for duration of breastfeeding among white infants from 2009 to 2015, black infants had only a 6.1 percentage-point increase for initiation or exclusivity of breastfeeding and a 9.4 percentage-point increase for breastfeeding duration). Although breastfeeding rates also became higher after controlling for sociodemographic factors, black infants continuously had lower breastfeeding rates than white infants even after adjustment (Table 2). Breastfeeding disparity between black and white infants became larger from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 for all 3 adjusted breastfeeding rates (Figure 2); specifically, the difference in rates increased from 3.7 to 5.8 percentage points in ever breastfeeding (DID, 2.1%), from 0.5 to 4.5 percentage points in exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months (DID, 4.0%), and from 2.0 to 3.7 percentage points in continued breastfeeding at 12 months (DID, 1.7%). All adjusted breastfeeding rates among black infants were statistically significantly lower than those among white infants in 2014-2015 (Figure 3).

Non-Hispanic Asian Infants

In contrast to Hispanic and black infants, Asian infants had lower adjusted breastfeeding rates than the corresponding crude rates (Table 2). Although Asian infants started with a higher initiation rate than white infants in 2009-2010, the rate became lower than white infants in 2014-2015, and the gap narrowed (DID, −0.9%) (Figure 2). Rates of exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months were higher among Asian infants compared with white infants in both 2009-2010 and in 2014-2015, but the gap narrowed (DID, −0.9%). On the contrary, the gap for continued breastfeeding at 12 months between Asian and white infants widened from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 (DID, 0.3%). After controlling for sociodemographic factors, Asian infants continuously had higher rates for breastfeeding continuation at 12 months in 2009-2010 (APR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.04-1.35) and 2014-2015 (APR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.24) compared with white infants (Figure 3).

Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native Infants

Similar to Hispanic and black infants, adjusted rates among American Indian or Alaskan Native infants were higher than the corresponding crude rates (eg, 78.4% vs 72.7% for initiation, 14.4% vs 12.1% for exclusivity, and 28.4% vs 23.3% for continued breastfeeding at 12 months in 2009-2010) (Table 2). The gaps between American Indian or Alaskan Native and white infants within each birth year generally became smaller after adjustment. For example, the differences in crude exclusive breastfeeding rates between American Indian or Alaskan Native and white infants were almost 6 percentage points, but they were only 1.0 percentage point in 2009-2010 (14.4% vs 15.4%) and 0.8 percentage point in 2014-2015 (24.7% vs 25.5%) using adjusted rates. Although no significant change in exclusive breastfeeding was found (DID, −0.2%), the gaps between American Indian or Alaskan Native and white infants in ever breastfeeding (DID, −3.9%) and continuation at 12 months (DID, −2.9%) narrowed significantly (Figure 2). None of the adjusted prevalence ratios were statistically significant among American Indian or Alaskan Native infants after controlling for demographic characteristics and socioeconomic status (eg, APRs in 2014-2015 were 0.98 for initiation [95% CI, 0.90-1.06], 0.97 for exclusivity [95% CI, 0.75-1.26], and 0.93 for continued breastfeeding at 12 months [95% CI, 0.73-1.17]) (Figure 3). Breastfeeding rates in the American Indian or Alaskan Native group fluctuated more than rates in the other groups annually because of the relatively smaller sample size in this group (eTable in the Supplement).

Discussion

Overall, there were steady increases in breastfeeding rates from 2009 to 2015 among all racial/ethnic groups except for ever breastfeeding among Asian and American Indian or Alaskan Native infants and continuation at 12 months among American Indian or Alaskan Native infants. Adjusted breastfeeding rates became higher than the corresponding crude rates among Hispanic, black, and American Indian or Alaskan Native infants but lower among white and Asian infants, which suggests that breastfeeding rates are partially associated with socioeconomic and demographic status. In addition to these changes from crude to adjusted rates within each race/ethnicity, the gaps between nonwhite and white infants within each birth year changed after the adjustment. Thus, it is important to account for the socioeconomic and demographic factors when examining the independent associations of race/ethnicity with breastfeeding disparity.

Despite significant increases in adjusted breastfeeding rates from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 among black infants, breastfeeding disparities became larger between black and white infants as rates among black infants decreased further below those among white infants in 2014-2015. Specifically, the disparity between black and white infants increased from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 by 2.1 percentage points for ever breastfeeding, 4.0 percentage points for exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months, and 1.7 percentage points for continued breastfeeding at 12 months. In contrast, the breastfeeding gaps between Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian or Alaskan Native infants and white infants became smaller from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015 except for continuation at 12 months among Asian infants. Because of positive trends among all races/ethnicities, these narrowed gaps were largely associated with greater increases among white infants throughout the study years.

Considerable breastfeeding progress from 2009 to 2015 might be a reflection of national and local efforts to increase breastfeeding support in the United States. For example, during the past decade, policies that protect women’s right to breastfeed in public and to have time and space to express milk at work have been enacted, training provided to physicians and other health care professionals has expanded, and access to professional lactation support has improved.2,13,14,15 In addition, there have been substantial achievements in hospitals implementing the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding as part of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI).16,17

Improving breastfeeding rates across all race/ethnicities and reducing inequities remain important public health goals.18 The poor breastfeeding practices may stem from a range of interrelated historical, cultural, social, economic, and psychosocial factors, as well as suboptimal policies and breastfeeding programs in certain settings.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 Many sociodemographic factors are associated with an increased likelihood of breastfeeding, such as older maternal age, being married, higher maternal educational level, and access to private insurance.28,29,30,31 Although adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics reduced the differences between black and white infants from crude estimates, the persistent significant differences suggest that breastfeeding disparities between black and white infants are, in part, independent of sociodemographic characteristics. On the other hand, adjusted analysis showed that Hispanic infants had higher breastfeeding rates than white infants, which was not apparent in the unadjusted analyses, suggesting that socioeconomic and demographic factors included in our models were associated with lower breastfeeding estimates from crude analysis among Hispanic infants.

Previous literature2,14 has reported that breastfeeding outcomes are significantly affected by maternity care practices and health care support. Black women may be less likely to receive adequate support. For example, 1 study32 found that maternity care practices supportive of breastfeeding were less likely to be implemented in birth facilities located in zip codes with a greater percentage of black residents. In addition to the services provided to breastfeeding mothers, the effectiveness of breastfeeding programs and policies may also vary by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.33

The BFHI has been associated with improved breastfeeding rates.34 A more recent study35 in the southern United States also found that BFHI was associated with reduced breastfeeding disparities among black infants. Because the current study is at the national level and only up to 2015, it is possible that those recent local efforts to reduce the disparities between black and white infants may not have become apparent yet in this study. Because socioeconomically advantaged individuals may tend to respond earlier to breastfeeding interventions and to a greater degree than those who are disadvantaged, it is also hypothesized that population-wide intervention strategies may inadvertently worsen inequalities.36,37,38 Thus, despite breastfeeding improvements among all races/ethnicities even after controlling for sociodemographic status, the widened disparities between black and white infants could be associated with relatively poor access or inequity of breastfeeding programs and supports provided to black mothers. Because of positive trends among all races/ethnicities, the reduced gaps in Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian or Alaskan Native populations were perhaps associated with lower rates at the start but greater increases over time among white infants. Given the large racial/ethnic variations in breastfeeding differentials, further studies are needed to identify the unique barriers for each individual group for targeted breastfeeding intervention.

Limitations

Although NIS-Child is designed to be nationally representative, this study has some known limitations, namely, the exclusion of households without telephones (noncoverage), the failure of some sample households to participate in the survey (nonresponse), and errors in respondents' reports (response bias). Survey weights are created to account for noncoverage and nonresponse rate. A previous study39 confirmed the validity and reliability of long-term maternal recall on breastfeeding initiation and continuation, but mixed results were found for maternal recall on exclusive breastfeeding duration. Because samples need to be independent to satisfy modeling assumptions, we could not compare each racial/ethnic group with the mean. Thus, white infants, who constitute the largest sample size, are used as the referent group in this study. However, the referent group should not be interpreted as the optimal standard for comparing groups.

Conclusions

Overall, breastfeeding rates increased from 2009 to 2015. The findings suggest that race/ethnicity has independent associations with breastfeeding after controlling for sociodemographic factors. Although breastfeeding disparities between black and white infants widened from 2009-2010 to 2014-2015, the gaps between Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian or Alaskan Native and white infants mostly narrowed in association with an accelerated increase among white infants. Continuing to improve breastfeeding supports and access to a variety of support services and professionals, with a specific emphasis on equity, may help improve breastfeeding rates among all women. Significant efforts are also needed to improve breastfeeding rates among black infants.

eTable. Characteristics of Study Samples Among Children Born From 2009 to 2015 (N = 167842)

References:

- 1.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2007. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 153 (prepared by Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-based Practice Center, under contract 290-02-0022). AHRQ publication 07-E007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feltner C, Weber RP, Stuebe A, Grodensky CA, Orr C, Viswanathan M. Breastfeeding Programs and Policies, Breastfeeding Uptake, and Maternal Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; July 2018. Comparative Effectiveness Review 210. AHRQ publication 18-EHC014-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Section on Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):-. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anstey EH, Chen J, Elam-Evans LD, Perrine CG. Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding—United States, 2011-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(27):723-727. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones KM, Power ML, Queenan JT, Schulkin J. Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(4):186-196. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen JA, Li R, Scanlon K, Perrine C, Chen J; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Progress in increasing breastfeeding and reducing racial/ethnic differences—United States, 2000-2008 births. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(5):77-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartick MC, Jegier BJ, Green BD, Schwarz EB, Reinhold AG, Stuebe AM. Disparities in breastfeeding: impact on maternal and child health outcomes and costs. J Pediatr . 2017;181:49-55 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 9.Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention National Immunization Survey Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/nis/about.html. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 10.Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention National Immunization Survey: Breastfeeding Rates. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/index.htm. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 11.Barker LE, Shaw KM. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: checking assumptions concerning regression residuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(3):533-539. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.113498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechner M. The estimation of causal effects by difference-in-difference method. Found Trends Econom. 2011;4(3):165-224. doi: 10.1561/0800000014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapinos KA, Bullinger L, Gurley-Calvez T. The Affordable Care Act, breastfeeding, and breast pump health insurance coverage. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1002-1004. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Primary care interventions to support breastfeeding: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1688-1693. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anstey EH, MacGowan CA, Allen JA. Five-year progress update on the Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding, 2011. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(8):768-776. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baby Friendly USA Celebrating 500 baby-friendly designated facilities in the United States, 2018. https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/news/baby-friendly-usa-celebrates-major-milestone-of-500-baby-friendly-designated-facilities-in-the-united-states/. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 17.Grossniklaus DA, Perrine CG, MacGowan C, et al. Participation in a quality improvement collaborative and change in maternity care practices. J Perinat Educ. 2017;26(3):136-143. doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.26.3.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Office of the Surgeon General (US) The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding . Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2011. Message from the Secretary, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thulier D. Breastfeeding in America: a history of influencing factors. J Hum Lact. 2009;25(1):85-94. doi: 10.1177/0890334408324452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guendelman S, Kosa JL, Pearl M, Graham S, Goodman J, Kharrazi M. Juggling work and breastfeeding: effects of maternity leave and occupational characteristics. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e38-e46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kogan MD, Singh GK, Dee DL, Belanoff C, Grummer-Strawn LM. Multivariate analysis of state variation in breastfeeding rates in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1872-1880. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer BS, Grassley JS. African American women and breastfeeding: an integrative literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(7):607-625. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.684813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeVane-Johnson S, Woods-Giscombé C, Thoyre S, Fogel C, Williams R. Integrative literature review of factors related to breastfeeding in African American women: evidence for a potential paradigm shift. Hum Lact. 2017;33(2):435-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, Fiese BH, Donovan SM. Breastfeeding is natural but not the cultural norm: a mixed-methods study of first-time breastfeeding, African American mothers participating in WIC. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(7):S151-S161.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith-Gagen J, Hollen R, Tashiro S, Cook DM, Yang W. The association of state law to breastfeeding practices in the US. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(9):2034-2043. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1449-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oyeku SO. A closer look at racial/ethnic disparities in breastfeeding: commentary on “Breastfeeding advice given to African American and white women by physicians and WIC counselors”. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):377-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills SP. Workplace lactation programs: a critical element for breastfeeding mothers’ success. AAOHN J. 2009;57(6):227-231. doi: 10.1177/216507990905700605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li R, Grummer-Strawn L. Racial/ethnic disparity in breastfeeding among United States infants: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988-1994. Birth. 2002;29:251-257. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skafida V. The relative importance of social class and maternal education for breast-feeding initiation. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(12):2285-2292. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009004947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahluwalia IB, Li R, Morrow B. Breastfeeding practices: does method of delivery matter? Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(suppl 2):231-237. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1093-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKinney CO, Hahn-Holbrook J, Chase-Lansdale PL, et al. ; Community Child Health Research Network . Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20152388. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind JN, Perrine CG, Li R, Scanlon KS, Grummer-Strawn LM; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(33):725-728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Victora CG, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Barros AJD, Horta BL, Barros FC. Breastfeeding and feeding patterns in three birth cohorts in Southern Brazil: trends and differentials. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(suppl 3):S409-S416. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2008001500006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, et al. ; PROBIT Study Group (Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial) . Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285(4):413-420. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merewood A, Bugg K, Burnham L, et al. Addressing racial inequities in breastfeeding in the southern United States. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20181897. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet. 2000;356(9235):1093-1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02741-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macintyre S, Chalmers I, Horton R, Smith R. Using evidence to inform health policy: case study. BMJ. 2001;322(7280):222-225. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7280.222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216-221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li R, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr Rev. 2005;63(4):103-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Characteristics of Study Samples Among Children Born From 2009 to 2015 (N = 167842)