Key Points

Question

What is the reliability of existing systematic reviews addressing interventions for 7 retina and vitreous conditions?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 327 systematic reviews of interventions for retina and vitreous conditions, 131 reviews (40.1%) were classified as reliable using prespecified criteria. Of the 196 reviews (59.9%) classified as not reliable, 149 reviews (76.0%) did not conduct a comprehensive literature search.

Meaning

Most systematic reviews on interventions for retina and vitreous conditions were unreliable; systematic review teams should routinely include information professionals as members to aid development and execution of search strategies appropriate to the goals of the review.

Abstract

Importance

Patient care and clinical practice guidelines should be informed by evidence from reliable systematic reviews. The reliability of systematic reviews related to forthcoming guidelines for retina and vitreous conditions is unknown.

Objectives

To summarize the reliability of systematic reviews on interventions for 7 retina and vitreous conditions, describe characteristics of reliable and unreliable systematic reviews, and examine the primary area in which they appeared to be lacking.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional study of systematic reviews was conducted. Systematic reviews of interventions for retina- and vitreous-related conditions in a database maintained by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision United States Satellite were identified. Databases that the reviewers searched, whether any date or language restrictions were applied, and bibliographic information, such as year and journal of publication, were documented. The initial search was conducted in March 2007, and the final update was performed in July 2018. The conditions of interest were age-related macular degeneration; diabetic retinopathy; idiopathic epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction; idiopathic macular hole; posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration; retinal and ophthalmic artery occlusions; and retinal vein occlusions. The reliability of each review was evaluated using prespecified criteria. Data were extracted by 2 research assistants working independently, with disagreements resolved through discussion or by 1 research assistant with verification by a senior team member.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Proportion of reviews that meet all of the following criteria: (1) defined eligibility criteria for study selection, (2) described conducting a comprehensive literature search, (3) reported assessing risk of bias in included studies, (4) described using appropriate methods for any meta-analysis performed, and (5) provided conclusions consistent with review findings.

Results

A total of 327 systematic reviews that addressed retina and vitreous conditions were identified; of these, 131 reviews (40.1%) were classified as reliable and 196 reviews (59.9%) were classified as not reliable. At least 1 reliable review was found for each of the 7 retina and vitreous conditions. The most common reason that a review was classified as not reliable was lack of evidence that a comprehensive literature search for relevant studies had been conducted (149 of 196 reviews [76.0%]).

Conclusion and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that most systematic reviews that addressed interventions for retina and vitreous conditions were not reliable. Systematic review teams and guideline developers should work with information professionals who can help navigate sophisticated and varied syntaxes required to search different resources.

This cross-sectional study of systematic reviews assesses the reliability of systematic reviews on interventions for 7 retina and vitreous conditions.

Introduction

For clinical practice guideline developers, systematic reviews are indispensable to identify and critically appraise available evidence needed to answer a clinical question.1 The National Academy of Medicine (formerly The Institute of Medicine until 2015) defines a systematic review as “a scientific investigation that focuses on a specific question and uses explicit, prespecified scientific methods to identify, select, assess, and summarize the findings of similar but separate studies.”1[p21]

Because systematic reviews are critical in underpinning clinical practice guidelines, the review approach is used increasingly frequently, but not all systematic reviews are reliable. Earlier investigations have yielded estimates of unreliable systematic reviews for different eyes and vision conditions of up to 70% of those evaluated.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 We classified systematic reviews as reliable when they used methods that aimed to reduce bias and errors in the systematic review process.2,8,9 These methods include defined eligibility criteria for selection of individual studies, a comprehensive literature search for eligible studies, an assessment of the risk of bias of the individual included studies, appropriate methods for meta-analyses (if done), and concordance between the review findings and conclusions.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Whenever we were not convinced that the systematic review teams had used recommended methods, we classified the review as not reliable. Systematic reviews classified as not reliable may contribute to suboptimal patient care1 or research waste.10,11

The cornerstone of a reliable systematic review is a comprehensive search for all of the evidence relevant to the research question. Systematic review teams who do not conduct a comprehensive search may not find all the evidence relevant to a given question.12 The findings of a systematic review cannot be reproduced if it does not fully report all information sources searched, a complete set of search terms used, and if the search date and justification for any date or language filter used are not completely reported.1 The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, the National Academy of Medicine Standards, and other respected guidance for conducting systematic reviews regard development of the search as a critical step.1,9,12 Reporting guidelines, such as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA), extensions of PRISMA, and the Methodological Expectations for Cochrane Intervention Reviews, include a well-documented search strategy as a mandatory item for reporting.9,13

Since 2014, the American Academy of Ophthalmology has partnered with the Cochrane Eyes and Vision United States Satellite (CEV@US) to identify reliable systematic reviews as the backbone of the academy’s updated clinical practice guidelines (Preferred Practice Pattern [PPP]).2,3,4,5,6,7 In earlier CEV@US collaborations with the academy, the CEV@US assessed the reliability of systematic reviews of interventions for refractive error, cataract, and corneal conditions. For most reviews classified as not reliable, the reviewers did not conduct a comprehensive search.2,3,4,5,6,7,14 In this report, we describe the CEV@US classification of reliable systematic reviews relevant to the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Retina/Vitreous Panel, which expects to publish 7 updated retina and vitreous PPPs in 2019. We further examined the search strategies described in the reviews classified as not reliable and identified areas where we judged them to be lacking.

Methods

Identifying Eligible Systematic Reviews

In collaboration with information professionals from the Johns Hopkins Welch Medical Library (C.T. and L.R.), CEV@US maintains a database of systematic reviews we have identified that focus on vision research and eye care. The initial search for reports of systematic reviews was conducted in March 2007; we updated the search in September 2009, April 2012, May 2014, March 2016, and July 2017. The final update for this study was conducted in July 2018 (full search strategies available in eTable 10 in the Supplement). Our intent is to update the database annually.

We considered a report eligible for our database if it declared that it was a systematic review or meta-analysis anywhere in the article text.2,3,4,5,6,7 We excluded reports that were available only in abstract form. Articles that did not use either of these terms were included whenever they met the National Academy of Medicine definition of a systematic review.1 According to the National Academy of Medicine definition, a systematic review may contain a meta-analysis (a statistical technique that combines quantitative results from similar but separate studies), although a meta-analysis is not a necessary part of a systematic review. Conversely, when a meta-analysis is done, it should always be in the context of a systematic review. Our database, however, includes self-described meta-analyses, regardless of whether a systematic review was conducted (eg, some of the articles may have combined effect sizes across unsystematically identified studies). For systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported in by more than 1 eligible article (eg, Cochrane reviews that had been updated since their initial publication or copublications of Cochrane reviews in other journals), we included in this study the most recent or complete version. We included “empty reviews” (systematic reviews that included no studies) because they inform researchers and funders of evidence gaps, that is, areas where high-quality research is lacking.9 An empty review can be reliable if the methods followed by the reviewers were robust.

The CEV@US research assistants classified each record in our database by broad condition categories (eg, retina, glaucoma, cornea). Our classification of reviews was verified by a senior faculty member (B.S.H.). We resolved discrepancies through discussion.

To be eligible for this investigation, each report had to focus on 1 or more interventions for conditions for at least 1 of the 7 conditions targeted for updating in the American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina/Vitreous PPP: (1) age-related macular degeneration; (2) diabetic retinopathy, including diabetic macular edema; (3) idiopathic epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction; (4) idiopathic macular hole; (5) posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration; (6) retinal and ophthalmic artery occlusions; and (7) retinal vein occlusions. For simplicity, we refer to the 7 conditions collectively as retina and vitreous conditions.

Assessing the Reliability of Systematic Reviews

We adapted an electronic data collection form developed and maintained in the Systematic Review Data Repository that we used in earlier CEV@US projects to assess the reliability of systematic reviews in eyes and vision.2,3,4,5,6,7 The form includes items related to methodologic characteristics of the reviews; we derived these items from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,8 the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews,15 and the PRISMA guidelines for reporting meta-analyses.13

We classified systematic reviews as reliable whenever the report met all of the following criteria: (1) defined eligibility criteria for selection of individual studies, (2) conducted a comprehensive literature search for eligible studies, (3) assessed the risk of bias in individual included studies using any method, (4) used appropriate methods for any meta-analysis performed, and (5) stated conclusions consistent with the review findings. We considered a systematic review as not reliable when 1 or more of these criteria were not met. Definitions applied to these criteria are included in Table 1. For all systematic review reports, we extracted information regarding the databases searched, whether any date or language restrictions were applied, and bibliographic information, such as year of publication and journal.

Table 1. Criteria for Reliable Systematic Reviews.

| Criterion | Definition Applied to Identified Systematic Reviews |

|---|---|

| Defined eligibility criteria | Described inclusion and/or exclusion criteria for eligible studies |

| Conducted comprehensive literature search | (1) Described an electronic search of ≥2 bibliographic databases, (2) used a search strategy comprising a mixture of controlled vocabulary and keywords, (3) reported using at least 1 other method of searching such as searching of conference abstracts, identified ongoing trials, complemented electronic searching by hand search methods (eg, checking reference lists), and contacted experts or authors of included studies |

| Assessed risk of bias of included studies | Used any method (eg, scales, checklists, or domain-based evaluation) designed to assess methodologic rigor of included studies |

| Used appropriate methods for meta-analysis (if relevant) | Used quantitative methods that (1) were appropriate for the study design analyzed (eg, maintained the randomized nature of trials, used adjusted estimates from nonrandomized studies), (2) correctly computed the study-specific weight for meta-analysis |

| Stated conclusions supported by results | Reported conclusions were consistent with findings, provided a balanced consideration of benefits and harms, and did not favor a specific intervention if there was lack of evidence |

For systematic reviews with an inadequate or inadequately reported search strategy (classified as not reliable), we tabulated the proportion of systematic reviews that reported on each of 7 fundamental elements of a comprehensive search strategy.2 These criteria entail whether the authors reported having (1) searched multiple bibliographic databases or justified why this was not necessary, (2) searched non–English-language studies or justified why this was not necessary, (3) searched for all possible years or justified why this was not necessary, (4) searched reference lists of included studies or for other study reports citing included studies, (5) contacted experts in the field or study authors to identify other potentially relevant reports, (6) searched for unpublished studies or studies that are otherwise inaccessible through searches of conventional bibliographic databases (eg, gray literature, such as internal company reports, newsletters, and conference abstracts not published formally in peer-reviewed journals or books), and (7) searched for ongoing studies (eg, study registers). For systematic reviews classified as reliable, we recorded additional information: the population, interventions compared, outcomes examined, number of studies included, number of participants or eyes included, and key findings. We also recorded objectives and conclusions from the abstract or, when an abstract was not available, from the conclusions section of the body of the article.

Until June 15, 2018, 2 staff members of the Cochrane Eyes and Vision United States Satellite worked independently to abstract data and then resolved discrepancies through discussion.16 After this date, data were abstracted by 1 research assistant and then verified by at least 1 more experienced member of the team (I.J.S., R.W.S., B.S.H, K.D., or T.L.).

Results

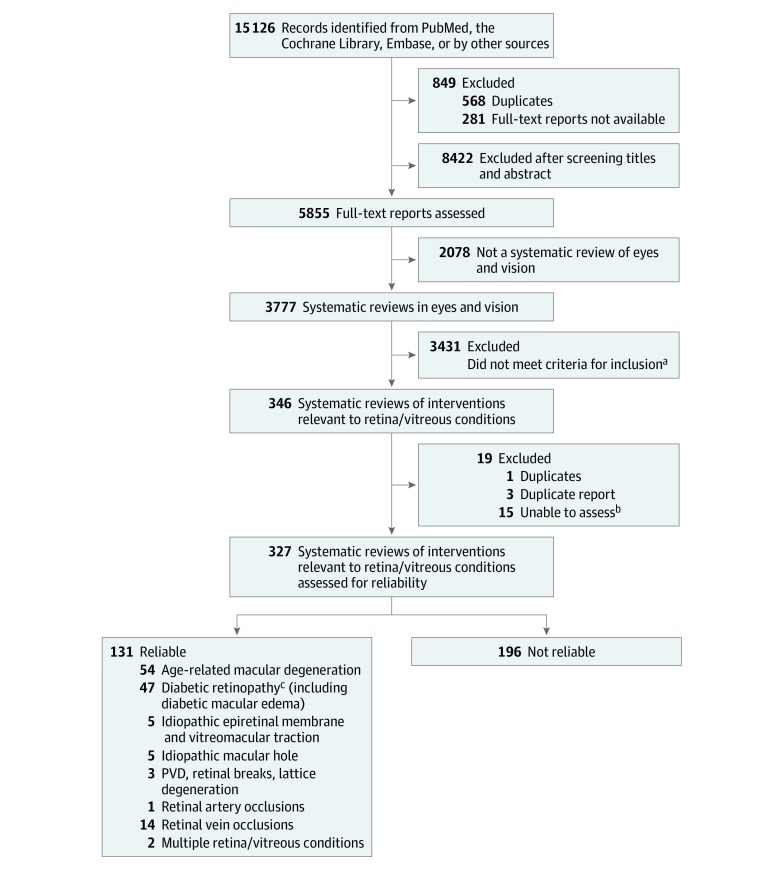

We identified 3777 eyes and vision systematic reviews for our database as of July 12, 2018; we classified 346 of these reviews (9.2%) as examining the association and safety of an intervention for retina and vitreous conditions (Figure 1). Because they were withdrawn from the database, were duplicates, or for other reasons, 19 reports were excluded; thus, we assessed the reliability of 327 systematic reviews. More than half of these 327 reviews (173 [52.9%]) were published in 2014 or after (median [interquartile range], 2014 [2010-2015]). Cochrane reviews (44 [13.5%]) and agency reports, such as Health Technology Assessments (23 [7.0%]), constituted a minority of the reviews; most reviews were published elsewhere (260 [79.5%]) (Table 2).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Depicting the Method of Identification of Systematic Reviews of Interventions for Retina/Vitreous Condition.

PVD indicates posterior vitreous detachment.

aExample of reasons for exclusion include not related to retina and vitreous conditions.

bExamples of inability to assess include not published in English or translatable or full text not available.

cIncluding diabetic macular edema.

Table 2. Characteristics of Systematic Reviews That Address Interventions for Retina and Vitreous Conditions by Reliability Classification.

| Characteristic | Systematic Reviews, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 327) | Classified as Reliable (n = 131) | Classified as Not Reliable (n = 196) | |

| Venue of systematic review publication | |||

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | 44 (13.5) | 44 (33.6) | 0 |

| Agency reports | 23 (7.0) | 13 (9.9) | 10 (5.1) |

| Other traditional journals | 260 (79.5) | 74 (56.5) | 186 (94.9) |

| Funding sources for the systematic reviewa | |||

| Government | 93 (28.4) | 59 (45.0) | 34 (17.3) |

| Pharmaceutical/other industry | 24 (7.3) | 7 (5.3) | 17 (8.7) |

| Foundation | 42 (12.8) | 14 (10.7) | 28 (14.3) |

| Academic institution or department | 56 (17.1) | 31 (23.7) | 25 (12.8) |

| Other funding source | 4 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) |

| Explicitly stated: none | 27 (8) | 5 (3.8) | 22 (11.2) |

| Not reported | 122 (37.3) | 31 (23.7) | 91 (46.4) |

| Databases searcheda | |||

| PubMed or MEDLINE | 286 (87.5) | 119 (90.8.) | 167 (85.2) |

| Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials | 219 (67.0) | 110 (84.0) | 109 (55.6) |

| Embase | 201 (61.5) | 106 (80.9) | 95 (48.5) |

| Latin American & Caribbean Health Sciences Literature | 32 (9.8) | 28 (21.4) | 4 (2.0) |

| Other | 131 (40.1) | 57 (43.5) | 74 (37.8) |

A systematic review could fulfill more than 1 of the categories.

Reliability of Systematic Reviews

We classified 131 of the 327 systematic reviews (40.1%) as reliable and 196 systematic reviews (59.9%) as not reliable. Systematic reviews classified as not reliable differed from reliable systematic reviews by where they were published, the funding the reviewers had received, and how the searches for included studies were conducted. For example, compared with reliable reviews, those that we classified as not reliable were published more often as articles in traditional journals (186 [94.9%] vs 75 [56.5%]) and did not report a funding source (91 [46.4%] vs 31 [23.7%]) (Table 2).

We identified at least 1 reliable systematic review for each of the 7 PPP retina and vitreous conditions: age-related macular degeneration (54 reviews); diabetic retinopathy (47 reviews); idiopathic epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction (5 reviews); idiopathic macular hole (5 reviews); posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration (3 reviews); retinal and ophthalmic artery occlusion (1 review); retinal vein occlusion (14 reviews); or multiple retina and vitreous conditions named above (2 reviews).

eTables 1-8 in the Supplement describe the objective, participants, interventions and comparators, numbers of studies and participants, and main conclusions of the 131 reliable systematic reviews. Ten reliable reviews (7.6%) were empty reviews (ie, they did not include any studies).

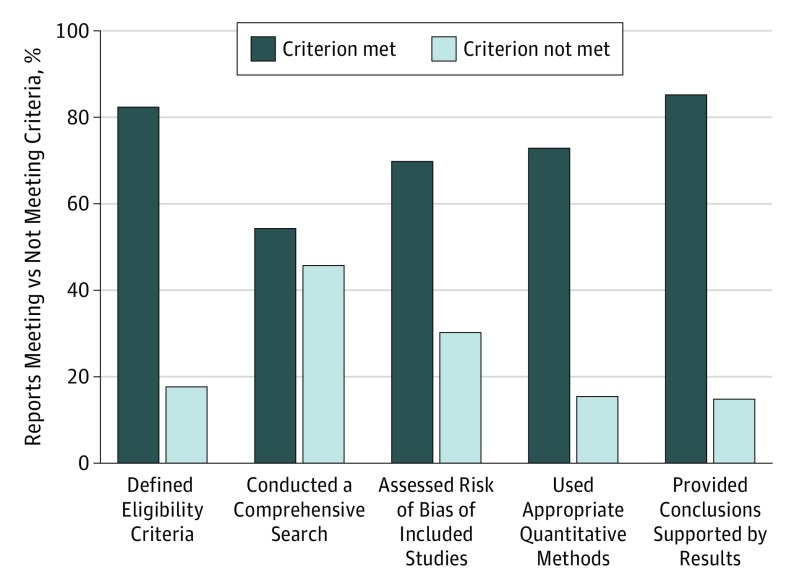

Of the 196 reviews classified as not reliable, the number of unmet criteria was 1 for 66 reviews (33.7%), 2 for 68 reviews (34.7%), 3 for 48 reviews (24.5%), 4 for 13 reviews (6.6%), and 5 for 1 review (0.5%). The most common unmet criterion was the lack of a comprehensive literature search for eligible studies (149 [76.0%]), followed by the lack of a risk of bias assessment of individual studies included in the review (98 [50.0%]) (Figure 2). Of the 149 systematic reviews that did not describe a comprehensive literature search for eligible studies, 34 reviews (22.8%) searched only 1 database and 15 reviews (10.1%) searched trial registries, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. Reviews that did not search multiple databases also had at least 1 or more other problems (Table 3). We found that other fundamental elements of a comprehensive search strategy often were not reported or, when reported, were implemented inadequately (Figure 2 and Table 3). For example, a systematic review team may have searched multiple databases, but did not use a comprehensive search strategy or inappropriately limited results by date and language.

Figure 2. Assessment of 327 Systematic Reviews of Interventions for Management of Retina/Vitreous Conditions by Reliability Criterion.

Table 3. Characteristics of Search Strategies for Systematic Reviews for Which an Adequate Literature Search Was Not Conducted (n = 149).

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not Reported | |

| Searched >1 database | 100 (67.1) | 34 (22.8) | 15 (10.1) |

| Searched non–English-language studies | 51 (34.2) | 58 (38.9) | 40 (26.8) |

| Searched for all possible years | 48 (32.2) | 54 (36.2) | 47 (31.5) |

| Searched reference lists | 72 (48.3) | 30 (20.1) | 47 (31.5) |

| Contacted experts in the field | 18 (12.1) | 68 (45.6) | 63 (42.3) |

| Searched for unpublished/difficult to access studiesb | 28 (18.8) | 69 (46.3) | 52 (34.9) |

| Searched for ongoing studiesb | 15 (10.1) | 72 (48.3) | 62 (41.6) |

Percentages are raw percentages.

Reviews that did not search other sources also did not meet 1 or more criterion in the table.

Discussion

Of 327 systematic reviews of interventions for retina and vitreous conditions, 131 were classified as reliable and addressed interventions for the 7 retina and vitreous conditions of interest. However, 196 systematic reviews were classified as not reliable based on our criteria. Of the reviews that we classified as not reliable, 76.0% had search strategies that we judged to be inadequate to be considered comprehensive.

Our findings that many systematic reviews in eyes and vision are apparently not reliable is in keeping with prior work. In age-related macular degeneration, for example, Lindsley and colleagues4 found that approximately 1 in 4 systematic reviews were not reliable, and Downie and colleagues17 observed that age-related macular degeneration reviews adhered to a mean of 6 of 11 Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews quality criteria. Similar problems with systematic reviews in other areas of ophthalmology have also been identified; the CEV@US has reported that systematic reviews were not reliable for interventions addressing refractive error (70%), cataract (54%), and corneal conditions (34%).6,7,14

Ophthalmology is a relatively small research field. Failure to conduct a comprehensive search can lead to omission of a potentially large proportion of studies, which may be a factor in supporting or changing current clinical practice. While it is possible that an incomplete or unreliable review could identify relevant studies, conclusions drawn in unreliable reviews are usually not based on the totality of evidence and may be subject to biased inclusion of studies.9 Furthermore, lack of explicit methods prevents other systematic review teams from replicating findings or the community from understanding why results and conclusions may differ among reviews.9,18

The purpose of a comprehensive search of the literature in systematic reviews is to identify all relevant studies.18,19,20,21 There are several actions that systematic review teams should take to ensure their searches are comprehensive (eTable 9 in the Supplement provides suggestions). First, systematic review teams should collaborate with information professionals knowledgeable about performing systematic reviews when developing search strategies. Information professionals, such as medical librarians, can help reviewers to determine which databases should be searched and the search terms and filters that should be used. Identifying all of the studies relevant to a given research question requires a search that is designed to be sufficiently sensitive and specific.22 Information professionals also can advise whether a search filter is appropriate for the research question. In comparing systematic reviews in which information specialists were involved in developing the searches with reviews that did not, the evidence suggests that reviews involving information specialists more often reported search strategies that can be reproduced.23,24,25

Second, for the search to be comprehensive, systematic review teams should search multiple sources to identify all eligible studies. Relevant study reports often are scattered across many journals, databases, study registries, gray literature, and other sources.22,23 Identifying the appropriate set of sources for a given question and searching them thoroughly requires familiarity with the technical aspects of data structure and databases and experience in document retrieval.22 Bibliographic databases, such as MEDLINE, Embase, and The Cochrane Library, are considered the minimum databases to be searched to identify studies of interest.9 We observed that the authors of most systematic reviews in our analysis had searched at least 1 of these databases; however, few had searched study registries to find ongoing, completed, and terminated studies and their results.26 Study registries, such as ClinicalTrials.gov, can serve as resources for identifying both completed studies that never have published outcomes and outcomes that have not been reported in published studies.26,27 For example, Ross et al28 estimated that only 46% of all completed studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov had been published, and Scherer et al27 found that a substantial amount of additional information on study design can be gleaned from this registry.

To make evidence-based decisions, health care professionals need sound and clinically relevant clinical practice guidelines.1 Organizations that develop and update clinical practice guidelines should seek to partner with organizations that specialize in evidence synthesis to identify reliable systematic reviews. Partnership between systematic review teams and guideline developers allows for efficient use of resources and ensures that higher-quality evidence is applied to support clinical practice.1,29

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Classification of reliability of reports of retina and vitreous systematic reviews was based on information from the reported methods and required our judgment; we did not contact the authors of the reviews for additional information. We focused on 5 reliability criteria applied to the systematic review report and not to the studies examined in the review. For example, a reliable systematic review may have found no evidence reported or may have found only reported evidence that the authors judged to be poor. We also did not evaluate the method used to assess risk of bias in individual studies. For example, the Jadad quality score is currently considered to be inadequate to assess risk of bias of studies included in systematic reviews,30,31 and yet we classified the review as meeting the criterion if they used such approach. Furthermore, although the body of evidence presented in the included studies in each review can be assessed using a framework, such as GRADE,32 making such assessments was beyond the scope of this investigation. In addition, it is possible that the systematic reviews we reviewed and judged to be reliable are now out-of-date, especially for conditions or interventions, such as antivascular endothelial growth factor treatment for retinal disorders, for which new studies are being published at a fast pace.

Conclusions

We classified 131 of 327 systematic reviews (40.1%) of interventions for retina and vitreous conditions as reliable to provide summarized evidence for topics of interest to the panels updating the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2019 Retina/Vitreous PPPs. Of the systematic reviews that we classified as not reliable, 76.0% did not conduct a comprehensive search for eligible studies. Systematic review teams should routinely include information professionals as members to aid development and execution of search strategies appropriate to the goals of the review.

eTable 1. Age-Related Macular Degeneration

eTable 2. Diabetic Retinopathy

eTable 3. Idiopathic Epiretinal Membrane & Vitreomacular Traction

eTable 4. Idiopathic Macular Holes

eTable 5. PVD, Retinal Breaks, & Lattice Degeneration

eTable 6. Retinal Artery Occlusions

eTable 7. Retinal Vein Occlusions

eTable 8. Multiple Retina/Vitreous Conditions

eTable 9. Steps for Searching to Support a Systematic Review

eTable 10. Search Strategy

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li T, Vedula SS, Scherer R, Dickersin K. What comparative effectiveness research is needed? a framework for using guidelines and systematic reviews to identify evidence gaps and research priorities. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):367-377. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu T, Li T, Lee KJ, Friedman DS, Dickersin K, Puhan MA. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research on management of primary angle closure: a survey of Asia-Pacific clinicians. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(5):348-355. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31829e5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsley K, Li T, Ssemanda E, Virgili G, Dickersin K. Interventions for age-related macular degeneration: are practice guidelines based on systematic reviews? Ophthalmology. 2016;123(4):884-897. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le JT, Hutfless S, Li T, et al. . Setting priorities for diabetic retinopathy clinical research and identifying evidence gaps. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(2):94-102. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayo-Wilson E, Ng SM, Chuck RS, Li T. The quality of systematic reviews about interventions for refractive error can be improved: a review of systematic reviews. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0561-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golozar A, Chen Y, Lindsley K, et al. . Identification and description of reliable evidence for 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology preferred practice pattern guidelines for cataract in the adult eye. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(5):514-523. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) CASP checklists. 2006.. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. Accessed January 22, 2019.

- 9.Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Updated 2011. Accessed January 22, 2019.

- 10.Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Research waste is still a scandal. BMJ. 2018;363:k4645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siontis KC, Ioannidis JPA. Replication, duplication, and waste in a quarter million systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(12):e005212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T, Bartley GB. Publishing systematic reviews in ophthalmology: new guidance for authors. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(2):438-439. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saldanha IJ, Lindsley KB, Lum F, Dickersin K, Li T. Reliability of the evidence addressing treatment of corneal diseases: a summary of systematic reviews. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(7):775-785. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. . Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jap J, Saldanha IJ, Smith BT, Lau J, Schmid CH, Li T; Data Abstraction Assistant Investigators . Features and functioning of Data Abstraction Assistant, a software application for data abstraction during systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(1):2-14. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downie LE, Makrai E, Bonggotgetsakul Y, et al. . Appraising the quality of systematic reviews for age-related macular degeneration interventions: a systematic review. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(9):1051-1061. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman S, Dickersin K. Metabias: a challenge for comparative effectiveness research. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):61-62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J Searching for studies. In: Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Updated 2011. Accessed January 22, 2019.

- 20.Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Holenstein F, Sterne J. How important are comprehensive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic reviews? empirical study. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(1):1-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6964):1286-1291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGowan J, Sampson M. Systematic reviews need systematic searchers. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93(1):74-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rethlefsen ML, Farrell AM, Osterhaus Trzasko LC, Brigham TJ. Librarian co-authors correlated with higher quality reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(6):617-626. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meert D, Torabi N, Costella J. Impact of librarians on reporting of the literature searching component of pediatric systematic reviews. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(4):267-277. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzendorf M. Why medical information specialists should routinely form part of teams producing high quality systematic reviews—a Cochrane perspective. J Eur Assoc Health Inf Libr. 2016;12(4):6-9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tse T, Fain KM, Zarin DA. How to avoid common problems when using ClinicalTrials.gov in research: 10 issues to consider. BMJ. 2018;361:k1452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherer RW, Huynh L, Ervin AM, Taylor J, Dickersin K. ClinicalTrials.gov registration can supplement information in abstracts for systematic reviews: a comparison study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Hines EM, Nissen SE, Krumholz HM. Trial publication after registration in ClinicalTrials.Gov: a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(9):e1000144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger VW, Alperson SY. A general framework for the evaluation of clinical trial quality. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2009;4(2):79-88. doi: 10.2174/157488709788186021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jadad AR. The merits of measuring the quality of clinical trials: is it becoming a Byzantine discussion? Transpl Int. 2009;22(10):1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GRADE Welcome to the GRADE working group. http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org. Accessed October 5, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Age-Related Macular Degeneration

eTable 2. Diabetic Retinopathy

eTable 3. Idiopathic Epiretinal Membrane & Vitreomacular Traction

eTable 4. Idiopathic Macular Holes

eTable 5. PVD, Retinal Breaks, & Lattice Degeneration

eTable 6. Retinal Artery Occlusions

eTable 7. Retinal Vein Occlusions

eTable 8. Multiple Retina/Vitreous Conditions

eTable 9. Steps for Searching to Support a Systematic Review

eTable 10. Search Strategy