Abstract

This study examines a trend in electronic cigarette use between 2017 and 2018 and stratifies results by sociodemographic categories.

Millions of Americans use electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). E-cigarettes may enable some people to quit smoking, but they may encourage others to start smoking, including susceptible populations, such as young people.1 Despite an increase in the number of people trying e-cigarettes, current use of e-cigarettes among US adults declined from 2014 to 2017 (weighted prevalence: 2014, 3.7%; 2015, 3.5%; 2016, 3.2%; 2017, 2.8%).2,3 Recently, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a startling rise in e-cigarette use among US middle school and high school students between 2017 and 2018, reversing the previously observed decline since 2015.4 This may be at least partly attributable to the recent popularity of pod-based e-cigarettes, such as the Juul brand.4 It is imperative to update the recent changes in e-cigarette use in adults to inform future research and policy. We updated data on adult e-cigarette use to include 2018 and examined the changes between 2017 and 2018.

Methods

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a leading annual health survey in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics, which conducts the survey, uses a multistage sampling strategy to allow nationally representative sampling of the noninstitutionalized civilian US population. The NHIS collects information about many health-associated topics through in-person household interviews.

The NHIS was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board. All respondents provided informed verbal consent prior to participation. The University of Iowa institutional review board determined the present study was exempt from approval because of the use of deidentified data.

Since 2014, participants aged 18 years or older were asked about their lifetime use of e-cigarettes2: “Have you ever used an e-cigarette, even 1 time?” Adults who had ever used an e-cigarette were then asked, “Do you now use e-cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” Current use of e-cigarettes includes using e-cigarettes every day or some days. Participants were also asked about lifetime and current use of conventional cigarettes (not including e-cigarettes).

Survey weights were used to account for unequal probability of selection and nonresponse. Overall differences in the prevalence of e-cigarette use across years were tested using x2 tests. Linear regression models were used to estimate the differences in prevalence between specific years. All data analyses were conducted using survey procedures in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

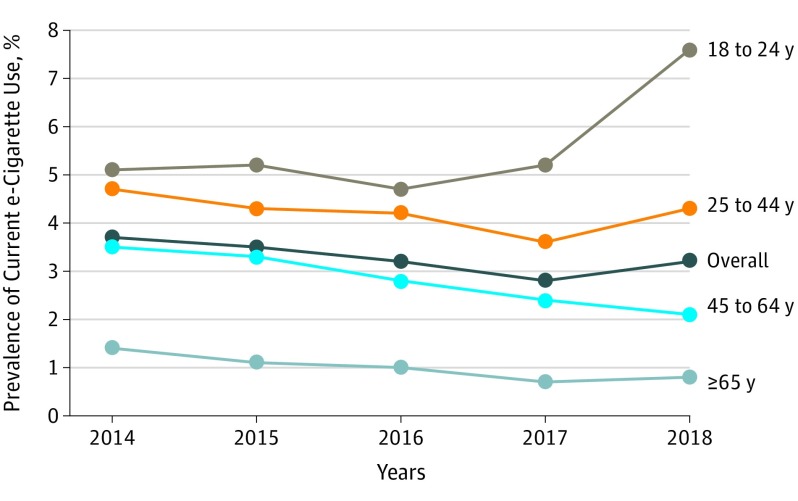

This analysis included 153 177 NHIS participants aged 18 years or older (of whom 84 154 [54.9%] were women). The weighted prevalence of current e-cigarette use decreased significantly from 3.7% (95% CI, 3.3%-4.1%) in 2014 to 2.8% (95% CI, 2.5%-3.1%) in 2017 and then increased to 3.2% (95% CI, 3.0%-3.5%) in 2018 (Figure).

Figure. Prevalence of Current Electronic Cigarette Use Among US Adults, 2014-2018 .

Prevalence estimates were weighted. The number of participants (n = 153 177) was 36 520 in 2014, 31 724 in 2015, 32 931 in 2016, 26 648 in 2017, and 25 354 in 2018. Overall differences in the prevalence of current electronic cigarette use from 2014 to 2018 were significant for the whole population (2014, 3.7% [95% CI, 3.3%-4.1%]; 2015, 3.5% [95% CI, 3.2%-3.7%]; 2016, 3.2% [95% CI, 2.9%-3.5%]; 2017, 2.8% [95% CI, 2.5%-3.1%]; 2018, 3.2% [95% CI, 3.0%-3.5%]; P < .001), adults aged 18 to 24 years (2014, 5.1% [95% CI, 3.5%-6.7%]; 2015, 5.2% [95% CI, 4.2%-6.2%]; 2016, 4.7% [95% CI, 3.5%-5.9%]; 2017, 5.2% [95% CI, 3.9%-6.5%]; 2018, 7.6% [95% CI, 6.1%-9.1%]; P = .02), adults aged 45 to 64 years (2014, 3.5% [95% CI, 2.9%-4.1%]; 2015, 3.3% [95% CI, 2.8%-3.7%]; 2016, 2.8% [95% CI, 2.4%-3.2%]; 2017, 2.4% [95% CI, 2.0%-2.7%]; 2018, 2.1% [95% CI, 1.8%-2.5%]; P < .001), and adults aged 65 years or older (2014, 1.4% [95% CI, 1.1%-1.8%]; 2015, 1.1% [95% CI, 0.8%-1.4%]; 2016, 1.0% [95% CI, 0.7%-1.2%]; 2017, 0.7% [95% CI, 0.5%-0.9%]; 2018, 0.8% [95% CI, 0.6%-1.1%]. The prevalence for adults aged 25 to 44 years did not differ significantly over time.

The increase in the prevalence of current e-cigarette use between 2017 and 2018 was highest among young adults aged 18 to 24 years old (difference between 2017 and 2018, 2.4% [95% CI, 0.4%-4.5%]; P = .02). In addition, a significant increase in the prevalence was observed among men (difference, 1.0% [95% CI, 0.4%-1.7%]; P = .002), non-Hispanic Asian individuals (difference, 1.3% [95% CI, 0.1%-2.4%]; P = .03), individuals with family income at least 4 times higher than the federal poverty level (difference, 1.0% [95% CI, 0.4%-1.6%]; P = .001), and those who formerly smoked conventional cigarettes (difference, 1.3% [95% CI, 0.3%-2.4%]; P = .01) (Table).

Table. Changes in the Prevalence Current Electronic Cigarette Use Among US Adults Between 2017 and 2018.

| Characteristic | Current Electronic Cigarette Usea Prevalence, % (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 (n = 26 648) | 2018 (n = 25 354) | Differencea | ||

| Overall | 2.8 (2.5-3.1) | 3.2 (3.0-3.5) | 0.4 (0.0-0.8) | .03 |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-24 | 5.2 (3.9-6.5) | 7.6 (6.1-9.1) | 2.4 (0.4-4.5) | .02 |

| 25-44 | 3.6 (3.1-4.2) | 4.3 (3.7-4.8) | 0.6 (–0.1 to 1.3) | .10 |

| 45-64 | 2.4 (2.0-2.7) | 2.1 (1.8-2.5) | –0.2 (–0.7 to 0.3) | .41 |

| ≥65 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 0.1 (–0.2 to 0.5) | .36 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 3.3 (2.8-3.7) | 4.3 (3.8-4.8) | 1.0 (0.4-1.7) | .002 |

| Women | 2.4 (2.0-2.7) | 2.3 (2.0-2.6) | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.4) | .67 |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.8 (1.1-2.5) | 2.5 (1.7-3.3) | 0.7 (–0.4 to 1.8) | .20 |

| Non-Hispanic | ||||

| White | 3.3 (2.9-3.6) | 3.7 (3.3-4.1) | 0.4 (–0.1 to 0.9) | .08 |

| Black | 2.2 (1.5-2.9) | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | –0.6 (–1.5 to 0.4) | .25 |

| Asian | 0.9 (0.4-1.4) | 2.2 (1.2-3.2) | 1.3 (0.1-2.4) | .03 |

| Other | 4.4 (2.3-6.5) | 5.7 (3.6-7.7) | 1.2 (–1.6 to 4.1) | .40 |

| Ratio of family income to poverty line | ||||

| <1.0 | 3.5 (2.8-4.2) | 4.0 (3.1-5.0) | 0.5 (–0.7 to 1.7) | .39 |

| 1.0-1.9 | 3.4 (2.7-4.0) | 3.9 (3.2-4.7) | 0.6 (–0.4 to 1.5) | .27 |

| 2.0-3.9 | 3.4 (2.8-4.0) | 4.0 (3.3-4.7) | 0.6 (–0.3 to 1.5) | .17 |

| ≥4.0 | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | 2.9 (2.5-3.4) | 1.0 (0.4-1.6) | .001 |

| Conventional cigarette smokingc | ||||

| Currently | 10.0 (8.8-11.1) | 9.7 (8.5-10.9) | –0.2 (–1.8 to 1.3) | .76 |

| Formerly | 4.2 (3.5-4.8) | 5.5 (4.7-6.3) | 1.3 (0.3-2.4) | .01 |

| Never | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 0.3 (–0.0 to 0.7) | .06 |

All estimates were weighted.

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were self-reported and classified based on the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

Conventional cigarette smoking did not include electronic cigarettes. Adults who had not smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were classified as never smokers. Adults who had ever smoked 100 cigarettes were classified as current smokers if they currently smoked every day or some days or former smokers if they were not currently smoking.

Discussion

Using nationally representative data in the United States, we found that the decline in current e-cigarette use among adults continued from 2014 to 2017 but was reversed between 2017 and 2018. A significant increase between 2017 and 2018 occurred among young adults, but no such increase occurred in middle-aged or older adults. The trends in young adults are similar to the previously reported trends in current e-cigarette use among US middle and high school students in 2017 and 2018.4 These findings are of public health concern, because nicotine exposure can harm the developing brain, and e-cigarette use may lead to a transition to subsequent cigarette smoking.5 The marketing and sales of e-cigarettes have changed sharply; Juul sales have surged since its introduction in 2015, with the brand capturing the greatest market share by 2017.6 With a discreet design and abundant types of flavors, Juul e-cigarettes are appealing to young people but also concerning because of their high nicotine content.6

A limitation of this study is that e-cigarette use was self-reported. Continued surveillance of e-cigarette use and public health interventions to decrease e-cigarette use among young adults are needed.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24952/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes. Published 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- 2.Bao W, Xu G, Lu J, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB. Changes in electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(19):2039-2041. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225-1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):157-164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788-797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King BA, Gammon DG, Marynak KL, Rogers T. Electronic cigarette sales in the United States, 2013-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1379-1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]