Abstract

The role of mitochondria in the fate determination of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) is not solely limited to the switch from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation, but also involves alterations in mitochondrial features and properties, including mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨmt). HSPCs have a high ΔΨmt even when the rates of respiration and phosphorylation are low, and we have previously shown that the minimum proton flow through ATP synthesis (or complex V) enables high ΔΨmt in HSPCs. Here we show that HSPCs sustain a unique equilibrium between electron transport chain (ETC) complexes and ATP production. HSPCs exhibit high expression of ETC complex II, which sustains complex III in proton pumping, although the expression levels of complex I or V are relatively low. Complex II inhibition by TTFA caused a substantial decrease of ΔΨmt, particularly in HSPCs, while the inhibition of complex I by Rotenone mainly affected mature populations. Functionally, pharmacological inhibition of complex II reduced in vitro colony-replating capacity but this was not observed when complex I was inhibited, which supports the distinct roles of complex I and II in HSPCs. Taken together, these data highlight complex II as a key regulator of ΔΨmt in HSPCs and open new and interesting questions regarding the precise mechanisms that regulate mitochondrial control to maintain hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal.

Keywords: Mitochondrial membrane potential, TMRM, HSC, SDHA, Electron transport chain, ATP synthase

1. Introduction

Adult mature blood cells are constantly being generated from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), moving through several lineage-committed progenitor stages in a highly tuned process, called hematopoiesis (Orkin and Zon, 2008). HSCs must limit mitochondrial respiration to remain in a quiescent state (Takubo et al., 2013; Warr and Passegue, 2013; Yu et al., 2013), while the metabolic profiles and mitochondrial functions of cells drastically change in the various stages of differentiation (Takubo et al., 2013; Ito and Suda, 2014; Ito et al., 2019).

Mitochondria are dynamic and complex organelles that play a critical role in many processes and functions as the major metabolic and bioenergetics organelles for the cell. In addition to apoptosis and calcium signaling, mitochondria regulate the electron transport chain (ETC) and ATP generation by oxidative phosphorylation (OxPHOS), as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity, and therefore contribute greatly to hematopoietic homeostasis (Ito and Suda, 2014; Chandel et al., 2016; Ito and Ito, 2018; Filippi and Ghaffari, 2019).

HSCs predominantly rely on glycolysis, but during differentiation a rapid switch to mitochondrial OxPHOS occurs, and this metabolic program is thought to be essential to driving their fate decisions regarding self-renewal or commitment, in addition to the adaptations required for specific microenvironments in the bone marrow niche (Simsek et al., 2010). The role of mitochondria in HSC fate determination is not limited to this metabolic adjustment, but also involves the alteration of mitochondrial features and properties (Papa et al., 2019; Maryanovich et al., 2015). It has been widely reported that HSCs exhibited an immature mitochondrial network with globular and primitive cristae and displayed a low metabolic profile supported by low mitochondrial ROS levels, mass and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨmt) (Papa et al., 2019; Vannini et al., 2016). Interestingly, however, these claims have recently come under renewed scrutiny. In particular, it was recently demonstrated that the dyes commonly used for the study of mitochondrial mass in bone marrow populations were affected by mitochondrial physiology, potentially biasing experimental conclusions (de Almeida et al., 2017; Bonora et al., 2018). Indeed, multiple studies using ΔΨmt-independent methods soon confirmed that mitochondrial content in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) had been consistently underestimated (de Almeida et al., 2017; Bonora et al., 2018).

Despite their high preference for glycolysis, mitochondria in HSCs have proven to be not completely inactive. Indeed, the importance of mitochondrial respiration for proliferation and HSC maintenance has been highlighted through studies of ΔΨmt and by challenges to the electron transport chain (Bejarano-Garcia et al., 2016; Anso et al., 2017; Umemoto et al., 2018). For example, inducible Succinate Dehydrogenase Complex Subunit D (SdhD)-ESR mutant mice exhibit a conditional SdhD gene (encoding a subunit of ETC complex II) mutant, which leads to a decrease in long-term HSCs and committed progenitors of the myeloid lineage (Bejarano-Garcia et al., 2016). Rieske iron‑sulfur protein (RISP), an essential subunit of ETC complex III, is necessary for maintaining adult HSC quiescence, and its loss by the deletion of Uqcrfs1 has been shown to lead to the severe pancytopenia (Anso et al., 2017).

Additionally, recent studies focused on ΔΨmt have further emphasized the importance of mitochondrial activity to HSC maintenance. Several research groups have used mitochondrial dyes to demonstrate bone marrow populations are heterogeneous in ΔΨmt and that long term multi-lineage reconstitution is enriched in low ΔΨmt fractions (Vannini et al., 2016; Sukumar et al., 2016). However, we need to pay attention to the activity of xenobiotic efflux pumps, as HSCs exhibit higher pump activity than mature populations, and this causes to the enhanced extrusion of mitochondrial dyes used for measuring ΔΨmt, such as tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) (Vannini et al., 2016; Goodell et al., 1997), which in turn can lead to biased results. Indeed, after treatment with Verapamil, an inhibitor of drug efflux pumps, HSPCs have shown higher ΔΨmt than mature hematopoietic cells (Bonora et al., 2018).

In this study, while considering the activity of xenobiotic efflux pumps in HSCs, we have assessed the equilibrium between ETC complexes and ATP production in HSPCs to better elucidate the mechanisms sustaining high ΔΨmt in HSPCs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

2.2. Mitochondrial membrane potential and superoxide production by flow cytometry

Bone marrow cells were isolated and stained for surface markers as previously described (Ito et al., 2016). Briefly, bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) were isolated with flushing protocol and were stained to detect different populations by flow cytometry. A mixture of monoclonal antibodies against CD4, CD8, CD3e, B220, TER-119, CD11b, Gr-1, IgM, CD19, CD127, and NK-1.1 was used as a lineage marker (Lineage, or Lin). Multipotent progenitors (MPPs) were identified as Lin− Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) CD135–, and HSCs as LSK CD135–CD150+CD48–. Antibody references are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

For mitochondrial membrane potential, cells were incubated with 2 nM TMRM or 1 μM JC-1 (Invitrogen), diluted in StemSPAN SFEM (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/ml SCF (Peprotech), 50 ng/ml TPO (Peprotec) and 50 μM Verapamil or 5 μM Cyclosporin H for 60 min (TMRM) at 37 °C, or 30 min (for JC-1) which is followed by wash.

For mitochondrial superoxide, cells were incubated with 1 μM MitoSOX™ (Thermofisher) diluted in Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 50 μM Verapamil. MitoSOX™ was incubated 30 min at 37 °C, then washed. Samples were acquired on a LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), then data analyzed using FlowJo 12 (TreeStar). For the treatment experiments, 160 nM Rotenone, 1.5 mM TTFA and 40 μM Antimycin A were added for 5 min before recording.

2.3. Cell sorting

Bone marrow cells were prepared as aforementioned, in addition cells were incubate with Anti-Biotin MicroBeads (10 μl beads per BM, Mylteni Biotech) for 10 min at room temperature, then flow through MACS LS column (Mylteni Biotech) for lineage depletion. Cells were sorted directly into StemSPAN SFEM through a BD FACS ARIA II (Becton Dickinson).

2.4. Immunofluorenscence

Sorted cells were resuspended in 50 μl of StemSPAN (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/ml SCF (Peprotech) and 50 ng/ml TPO (Peprotech) then seeded on Lab-Tek™ II Chamber Slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coated with Retronectin (Clonetech). Samples were then immunostained as described previously (Bonora et al., 2018). Rabbit anti-Ki67 (D3B5, CST, dilution 1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-TOM20 (FL-145, Santa Cruz, dilution 1:100), mouse monoclonal anti-ATP5A1 (15H4C4, Invitrogen, dilution 1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-NDUFV1 (Novusbio, dilution 1:100) and mouse monoclonal anti-SDHA (2E3GC12FB2AE2, abcam, dilution 1:100) were used for the detection. Z-stack were acquired on a Leica SP5 equipped with 63× oil immersion lens (NA 1.4), pinhole set at 1 airy unit with voxel size 80/200 nm on XY/Z. Stacks were deconvolved using the Richardson-Lucy algorithm (Sage et al., 2017) using measured PSF. Representative image renderings were obtained by Imaris 7 (Bitplane).

2.5. Quantitative colony forming capacity after long-term in vitro culture

8, 4, 2 and 1 HSCs (LSK CD135–CD150+CD48–) were sorted and cultured as previously reported (Ito et al., 2012; Song et al., 2013). For the treatment experiments, 0.45 nM Rotenone, 100 μM TTFA and/or 0.15 μM Antimycin A were added and the medium was changed two time a week for a total of 6 weeks. The frequency of cells with colony forming capacity after long-term in vitro culture was calculated using ELDA (extreme limiting dilution analysis) (Hu and Smyth, 2009). In each experiment, at least 12 replicates of each dilution were performed, and L-Calc™ Software (StemCell technologies) was used to assess the differences between the two conditions.

2.6. Quantification and statistical analysis

Normality assumption was verified with the D’Agostino-Pearson Omnibus Test. All the groups were filtered for eventual outliers using the ROUT method and tested through one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

3. Results

3.1. HSCs show high mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial functionality is reflected by ΔΨmt, which thereby represents a key parameter in the study of the HSC metabolism. Since xenobiotic efflux pump activity is higher in HSCs compared to mature cells (Goodell et al., 1997), the administration of Verapamil, an efflux pump inhibitor, is required for the accurate measurement of ΔΨmt by TMRM dye (de Almeida et al., 2017; Bonora et al., 2018). Flow analysis of HSCs (Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+CD135–CD150+CD48−), MPP (Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+CD135–), lineage negative (Lin−) and positive (Lin+) bone marrow populations (Oguro et al., 2013), stained by TMRM showed a downward trend in ΔΨmt along with hematopoietic differentiation (Fig. 1A). The administration of Cyclosporine H (CsH), a Ca2+-independent multidrug resistance inhibitor (Nicolli et al., 1996) (Supplementary Fig. 1A), and the analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using another ratio-metric dye probe, the dye JC-1 (tetraethylbenzimi-dazolylcarbocyanine iodide) (Supplementary Fig. 1B), confirmed that HSCs have the highest ΔΨmt among bone marrow populations.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial membrane potential decrease with differentiation. (A) HSC, MPP, Lin− and Lin+ bone marrow fractions were sorted and stained as described in the Material and Method section. TMRM intensity levels in HSCs, MPPs, Lin− and Lin+ fraction measured by flow cytometry and normalized on bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs)’ TMRM intensity. (B) Representative gating strategy for sorting of 30% TMRM lowest (Lo) and 30% TMRM highest (Hi) intensity MPP, and same gating applied to HSC fraction. (C) Representative images and (D) quantification of % of ki67+ cells (labeled by grey circles) on total cells (DAPI) in sorted HSC, MPP, MPP-Hi and MPP-Lo fractions. (E) Quantification of ki67+ cells as a percentage of total cells in sorted HSC-Hi and HSC-Lo fractions. Error bars represent mean with SD. At least three mice were analyzed per each experiment and the sample size for flow data for each group is shown by dots. ANOVA test (A, D) and t-test (E) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n.s. stands for no significant change.

To validate high ΔΨmt as a key feature of HSCs, we measured ki67 positivity to assess whether ΔΨmt is associated with cell cycle quiescence in HSPCs (Passegue et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2008). MPPs were separated into two fractions, based on their TMRM intensity, specifically, 30% of lowest and highest intensity MPPs (MPP-Lo and MPP-Hi, respectively), and stained for ki67 (Fig. 1B). HSCs and unfractionated MPPs were used as staining controls for quiescent and proliferative populations, respectively. As expected, the percentage of ki67+ cells in MPP-Hi was lower than the one in MPP-Lo, and were comparable to HSCs (Fig. 1C, D). Consistently, phenotypic HSCs preferentially reside in the Hi-TMRM fraction (~43%) (Fig. 1B), with less ki67 positivity (Fig. 1E). These data showed that the quiescent cells were enriched in the MPP-Hi and especially the HSC-Hi fractions, which supports our hypothesis of a close link between ΔΨmt and the cell cycle state of HSPCs.

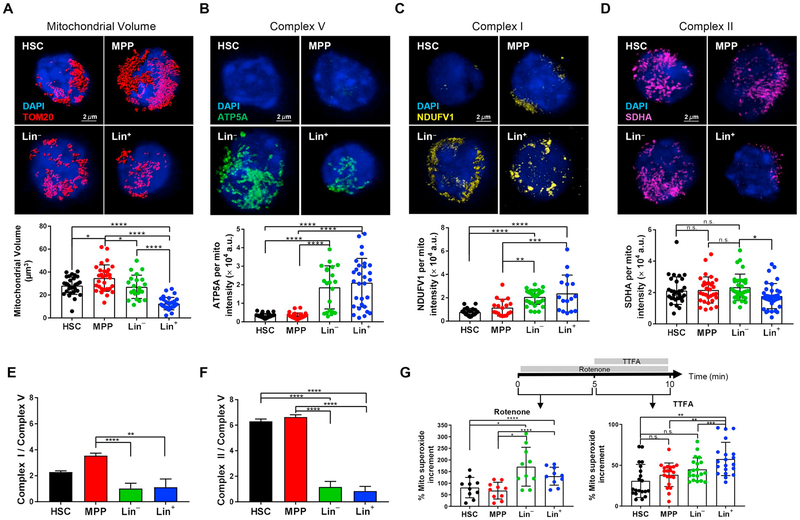

3.2. ETC complex II: complex V ratio is high in HSPCs

ΔΨmt represents a balance between proton pumping activity in the ETC and the proton flow through F1/FO ATP synthase (hereafter referred as complex V). We next assessed mitochondrial ETC complex subunits. Because mitochondrial content changes during differentiation stages ((Bonora et al., 2018) and Fig. 2A), the expression levels of these subunits were analyzed for single mitochondrion. The observed low levels of ATP production in HSCs (de Almeida et al., 2017) indicated that the expression of ATP5A, the fundamental subunit of complex V, was particularly weak in HSPCs and drastically increased following the differentiation process (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

The balance among electron transport chain complexes highlights the role of complex II in HSPCs. (A–F) HSC, MPP, Lin− and Lin+ bone marrow fractions were sorted and stained as described in Material and Method section. Representative images and quantification of mitochondrial content in single cell, identified by volume rendering of TOM20 (A). Representative images and quantification of (B) ATP5A, subunit of complex V, (C) NDUFV1, subunit of complex I, (D) SDHA, subunit of complex II, intensity measured for single mitochondria. Ratio of expression levels between complex I and complex V (E) and of complex II and complex V (F) in each bone marrow fraction. (G) Complex I and complex II activity measured by the increment in MitoSOX™ intensity followed by the addition of Rotenone (bottom left) and TTFA (bottom right) detected by flow cytometry in HSC, MPP, Lin− and Lin+ bone marrow fractions. Schematic of Rotenone and TTFA administration is also shown (top). Error bars represent mean with SD (A-D, G), or SEM in (E, F). At least three mice were analyzed per each experiment and the sample size for flow data for each group is shown by dots. ANOVA test *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n.s. stands for no significant change.

Complexes I, III and IV, are considered the energy-conserving core of the ETC because they pump protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane (Brand and Nicholls, 2011). In complex III, the electrons from both complex I and complex II converge, and we therefore analyzed the levels of subunits NADH: Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Core Subunit V1 (NDUFV1, for complex I) and SDHA (for complex II), respectively. Consistent with previous observations of the metabolic switch during HSC differentiation, the expression of complex I per single mitochondrion increased with hematopoietic maturation: Lin− and Lin+ showed significantly higher levels of NDUFV1 than HSCs or MPPs (Fig. 2C). To confirm complex I activity in hematopoietic lineages, we next assessed the incremental change in mitochondrial superoxide production following the addition of a complex I inhibitor, Rotenone. Mitochondrial superoxide basal levels differed among bone marrow populations (Supplementary Fig. 2A), and mitochondrial superoxide production as measured by MitoSOX in the presence of Verapamil was calculated as an incremental percentage after drug addition, to normalize each population to its own basal level. As expected, higher increases in mitochondrial superoxide were found in Lin− and Lin+ cells (Fig. 2G, left panel).

We next assessed complex II activity by MitoSOX. Accuracy in these measurements requires complex I first be inhibited by Rotenone, to prevent reverse electron transfer to complex I (Salabei et al., 2014), prior to the additional increment of MitoSOX by TTFA (Fig. 2G and Supplementary Fig. 2B). Interestingly, no differences were detected in SDHA expression or complex II activity between HSCs and mature populations (Fig. 2D and G, right panel). The effect of Antimycin A, a complex III inhibitor, on MitoSOX was then investigated (Drose et al., 2009). A major increase in mitochondrial superoxide after the addition of Antimycin A was found in Lin−, which was consistent with the critical roles played by complex III activity during the hematopoietic differentiation process (Anso et al., 2017), but only an incremental increase was observed in the HSC and MPP fractions (Supplementary Fig. 2C).

ETC complexes I-IV contributed to an increase in ΔΨmt, but complex V activity uncoupled to dissipate ΔΨmt. We also calculated the respective ratios of complex I and II to complex V (Fig. 2E and F, respectively). Compared to complex I (~2 times), a significantly higher ratio of complex II/complex V (~6 times) was found in HSPCs. Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that HSPCs have low ATP production levels, but also have limited ETC coupling capacity, which gives rise to high ΔΨmt.

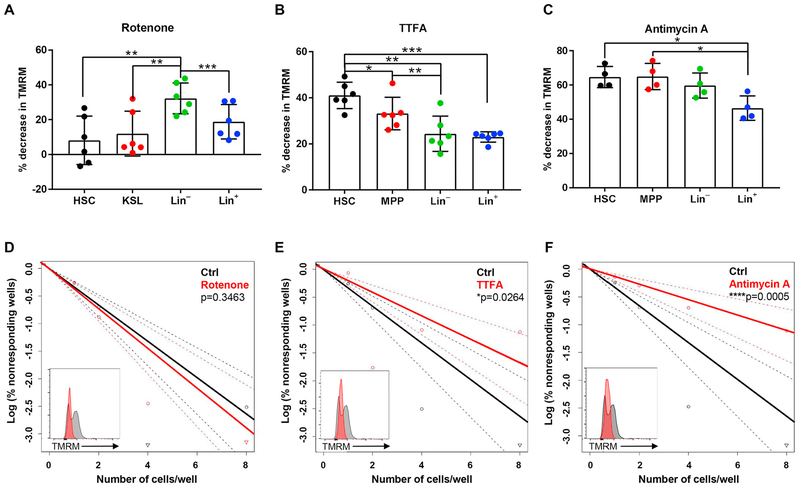

3.3. Inhibition of complex II mainly affects ΔΨmt in HSCs, leading to a reduction of their colony replating capacity in vitro

In order to deeply investigate the contribution of complex I, II and III to sustaining ΔΨmt, the reduction of TMRM intensity after the administration of their specific inhibitors was analyzed. Consistent with high complex I expression and activity in Lin− cells, the reduction of TMRM intensity by Rotenone was observed in Lin− and Lin+ cells (Fig. 3A), suggesting that these populations rely on complex I in contrast to HSPCs. Critically, the greatest reduction (~40%) of ΔΨmt by TTFA administration was found in HSCs, which showed significantly larger declines than Lin− and Lin+ (~20%) (Fig. 3B). Antimycin A was used to assess complex III activity. As expected, the addition of Anti-mycin A caused a drop in TMRM intensity (~45–60%) in all HSCs, MPPs and Lin− cells (Fig. 3C). We went on to perform sequential pharmacological inhibition of complex I, II and III in hematopoietic lineages to determine the contributions of each complex to their respective ΔΨmt. These experiments, together with the highest ratio of complex II: complex I in HSCs, confirmed that complex II was the greatest contributor to sustaining ΔΨmt in HSCs (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Complex II inhibition, differentially from complex I, causes a drop in ΔΨmt of HSPC and affects in vitro colony replating capacity. (A–C) Quantification of % TMRM decrease after addition of Rotenone, inhibitor of complex I (A), TTFA, inhibitor of complex II (B), and Antimycin A inhibitors of complex III (C) detected by flow cytometry in HSCs, MPPs, Lin− and Lin+ cells. (D-F) Limiting dilution assay to measure the frequencies of HSC with colony forming capacity after 6 weeks of in vitro culture in presence of Rotenone (D), TTFA (E) and Antimycin A (F) compared to Ctrl condition (the same control was used for the three drugs). The TMRM intensity of live mononuclear cells after 1 week of in vitro treatment is also shown (insets). Error bars represent mean with SD. At least three mice were analyzed per each experiment and the sample size for flow data for each group is shown by dots. ANOVA test (A–C) and t-test (D–F) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Finally, to investigate the functional importance of each ETC complex in HSPCs, in vitro long-term cultures of HSCs were performed in the presence of Rotenone, TTFA and Antimycin A. We first optimized the culture condition with these inhibitors, and confirmed that the low dosage used in our experiments to reduce ΔΨmt did not induce a significant increase of cell death, as shown by the percentage of DAPI+ BM-MNCs after 7 days of in vitro culture (Supplementary Fig. 4). After 6 weeks of in vitro cultures, Rotenone treatment reduced ΔΨmt, but did not show a significant difference in colony formation (Fig. 3D). On the other hand, TTFA caused a reduction in colony-forming capacity (Fig. 3E), and a similar effect was observed for Antimycin A (Fig. 3F). These data highlight the critical role of complex II in the maintenance of HSPCs.

4. Discussion

Mitochondria play a pivotal role in several biological functions, including proliferation, differentiation, and adaptation to stress, due to their ability to produce energy and support biosynthesis (Martinez-Reyes et al., 2016). Both ATP production and the TCA cycle rely on ETC. ETC provides the driving force for generating ATP through complex V, while in the TCA cycle complex II catalyzing the reaction that converts succinate to fumarate. The regulation of mitochondrial physiology (e.g. ΔΨmt) is considered one of the key cell-intrinsic biological signals in the process of HSC maintenance (Chandel, 2015).

Our HSC analysis showed that a relatively high number of mitochondria (de Almeida et al., 2017; Bonora et al., 2018) were inactive in the production of ATP or ROS, but these may still be critical to other as-yet unknown mechanisms which will only be revealed by continued investigation. Recent questions about the high activity of xenobiotic efflux pumps in HSCs have led to the establishment of proper protocols for flow cytometry analysis of ΔΨmt by TMRM dye. These methods have shown ΔΨmt is higher in HSPCs than in more mature populations ((Bonora et al., 2018; Morganti et al., 2019), and Fig. 1A).

This, however, raises several new questions, including how and why ΔΨmt is sustained at a high level in HSPCs. The balance between proton pumping (by ETC) and proton flow (by complex V) determine ΔΨmt levels in the cells. In this study, we have demonstrated that the expression levels of complex II relative to complex V are higher in HSPCs than in differentiated cells. Additionally, our data regarding the strong effect of TTFA on ΔΨmt (Fig. 3B) supports the notion that complex II is a key component responsible for maintaining high ΔΨmt in HSPCs (Fig. 2F). Although this study examined the roles of complex II under in vitro culture conditions, a previous study with SdhD mutant mice demonstrated that complex II function was essential for HSC survival and maintenance. SDH (alias complex II) is involved both in ETC and TCA, but it has been challenging to determine its precise role(s) or regulatory pathways in HSCs. Interestingly, fumarate hydratase (Fh1), another enzyme of the TCA cycle which catalyzes the reaction from fumarate to malate, has been proposed as another contributor to the maintenance of adult HSPCs (Guitart et al., 2017). If this is the case, it would support our idea that the role of complex II in TCA cycle also contributes to HSC maintenance.

5. Conclusions

Elucidating the mechanisms that sustain HSC self-renewal is key to our understanding of hematopoietic homeostasis as well as the development of new strategies for HSC transplantation.

This study identifies interesting new roles for ETC complex II. Even if complex II does not act as an active proton pump, its activity is fundamental to sustaining high ΔΨmt and ultimately in vitro colony replating capacity. In contrast to complex I, the expression of complex II is not affected by the metabolic switch that occurs during differentiation, which supports the idea that complex II may be involved in other pathways that maintain HSC homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the Ito laboratory, especially H Sato, and the Einstein Stem Cell Institute for comments and the Einstein Flow Cytometry and Analytical Imaging core facilities (funded by National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA013330) for help carrying out the experiments. Ke.I. is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK98263, R01DK115577, and R01HL148852) and the New York State Department of Health as Core Director of Einstein Single-Cell Genomics/Epigenomics (C029154). Ke. I. is a Research Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (1360–19). C.M. is supported by NYSTEM Einstein Training Program in Stem Cell Research. Support for The Einstein Training Program in Stem Cell Research of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Inc. is acknowledged from the Empire State Stem Cell Fund through New York State Department of Health Contract C30292GG. Opinions expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Empire State Stem Cell Board, the New York State Department of Health, or the State of New York.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2019.101573.

References

- Anso E, Weinberg SE, Diebold LP, Thompson BJ, Malinge S, Schumacker PT, Liu X, Zhang Y, Shao Z, Steadman M, Marsh KM, Xu J, Crispino JD, Chandel NS, 2017. The mitochondrial respiratory chain is essential for haematopoietic stem cell function. Nat. Cell Biol 19, 614–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano-Garcia JA, Millan-Ucles A, Rosado IV, Sanchez-Abarca LI, Caballero-Velazquez T, Duran-Galvan MJ, Perez-Simon JA, Piruat JI, 2016. Sensitivity of hematopoietic stem cells to mitochondrial dysfunction by SdhD gene deletion. Cell Death Dis 7, e2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonora M, Ito K, Morganti C, Pinton P, Ito K, 2018. Membrane-potential compensation reveals mitochondrial volume expansion during HSC commitment. Exp. Hematol 68, 30–37 e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG, 2011. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem. J 435, 297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, 2015. Evolution of mitochondria as signaling organelles. Cell Metab 22,204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Jasper H, Ho TT, Passegue E, 2016. Metabolic regulation of stem cell function in tissue homeostasis and organismal ageing. Nat. Cell Biol 18, 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida MJ, Luchsinger LL, Corrigan DJ, Williams LJ, Snoeck HW, 2017. Dye-independent methods reveal elevated mitochondrial mass in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. Stem Cell 21, 725–729 (e724). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drose S, Hanley PJ, Brandt U, 2009. Ambivalent effects of diazoxide on mitochondrial ROS production at respiratory chain complexes I and III. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790, 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi MD, Ghaffari S, 2019. Mitochondria in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells: new perspectives and opportunities. Blood 133, 1943–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, Marks DF, DeMaria M, Paradis G, Grupp SA, Sieff CA, Mulligan RC, Johnson RP, 1997. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat. Med 3, 1337–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitart AV, Panagopoulou TI, Villacreces A, Vukovic M, Sepulveda C, Allen L, Carter RN, van de Lagemaat LN, Morgan M, Giles P, Sas Z, Gonzalez MV, Lawson H, Paris J, Edwards-Hicks J, Schaak K, Subramani C, Gezer D, Armesilla-Diaz A, Wills J, Easterbrook A, Coman D, So CW, O’Carroll D, Vernimmen D, Rodrigues NP, Pollard PJ, Morton NM, Finch A, Kranc KR, 2017. Fumarate hydratase is a critical metabolic regulator of hematopoietic stem cell functions. J. Exp. Med 214, 719–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Smyth GK, 2009. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J. Immunol. Methods 347, 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Ito K, 2018. Hematopoietic stem cell fate through metabolic control. Exp. Hematol 64, 1–11. 10.1016/j.exphem.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Suda T, 2014. Metabolic requirements for the maintenance of self-renewing stem cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15, 243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Carracedo A, Weiss D, Arai F, Ala U, Avigan DE, Schafer ZT, Evans RM, Suda T, Lee CH, Pandolfi PP, 2012. A PML-PPAR-delta pathway for fatty acid oxidation regulates hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat. Med 18, 1350–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Turcotte R, Cui J, Zimmerman SE, Pinho S, Mizoguchi T, Arai F, Runnels JM, Alt C, Teruya-Feldstein J, Mar JC, Singh R, Suda T, Lin CP, Frenette PS, Ito K, 2016. Self-renewal of a purified Tie2+ hematopoietic stem cell population relies on mitochondrial clearance. Science 354, 1156–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Bonora M, Ito K, 2019. Metabolism as master of hematopoietic stem cell fate. Int. J. Hematol 109, 18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Reyes I, Diebold LP, Kong H, Schieber M, Huang H, Hensley CT, Mehta MM, Wang T, Santos JH, Woychik R, Dufour E, Spelbrink JN, Weinberg SE, Zhao Y, DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS, 2016. TCA cycle and mitochondrial membrane potential are necessary for diverse biological functions. Mol. Cell 61, 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryanovich M, Zaltsman Y, Ruggiero A, Goldman A, Shachnai L, Zaidman SL, Porat Z, Golan K, Lapidot T, Gross A, 2015. An MTCH2 pathway repressing mitochondria metabolism regulates haematopoietic stem cell fate. Nat. Commun 6, 7901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganti C, Bonora M, Ito K, 2019. Improving the accuracy of flow cytometric assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells through the inhibition of efflux pumps. J. Vis. Exp [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolli A, Basso E, Petronilli V, Wenger RM, Bernardi P, 1996. Interactions of cyclophilin with the mitochondrial inner membrane and regulation of the permeability transition pore, and cyclosporin A-sensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem 271, 2185–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguro H, Ding L, Morrison SJ, 2013. SLAM family markers resolve functionally distinct subpopulations of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Cell. Stem Cell 13, 102–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH, Zon LI, 2008. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology.Cell 132, 631–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa L, Djedaini M, Hoffman R, 2019. Mitochondrial role in stemness and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells Int 2019, 4067162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passegue E, Wagers AJ, Giuriato S, Anderson WC, Weissman IL, 2005. Global analysis of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression in the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fates. J. Exp. Med 202, 1599–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage D, Donati L, Soulez F, Fortun D, Schmit G, Seitz A, Guiet R, Vonesch C, Unser M, 2017. DeconvolutionLab2: an open-source software for deconvolution microscopy. Methods 115, 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salabei JK, Gibb AA, Hill BG, 2014. Comprehensive measurement of respiratory activity in permeabilized cells using extracellular flux analysis. Nat. Protoc 9, 421–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek T, Kocabas F, Zheng J, Deberardinis RJ, Mahmoud AI, Olson EN, Schneider JW, Zhang CC, Sadek HA, 2010. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 7, 380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SJ, Ito K, Ala U, Kats L, Webster K, Sun SM, Jongen-Lavrencic M, Manova-Todorova K, Teruya-Feldstein J, Avigan DE, Delwel R, Pandolfi PP, 2013. The oncogenic microRNA miR-22 targets the TET2 tumor suppressor to promote hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and transformation. Cell. Stem Cell 13, 87–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumar M, Liu J, Mehta GU, Patel SJ, Roychoudhuri R, Crompton JG, Klebanoff CA, Ji Y, Li P, Yu Z, Whitehill GD, Clever D, Eil RL, Palmer DC, Mitra S, Rao M, Keyvanfar K, Schrump DS, Wang E, Marincola FM, Gattinoni L, Leonard WJ, Muranski P, Finkel T, Restifo NP, 2016. Mitochondrial membrane potential identifies cells with enhanced stemness for cellular therapy. Cell Metab 23, 63–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takubo K, Nagamatsu G, Kobayashi CI, Nakamura-Ishizu A, Kobayashi H, Ikeda E, Goda N, Rahimi Y, Johnson RS, Soga T, Hirao A, Suematsu M, Suda T, 2013. Regulation of glycolysis by Pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. Stem Cell 12, 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto T, Hashimoto M, Matsumura T, Nakamura-Ishizu A, Suda T, 2018. Ca (2+)-mitochondria axis drives cell division in hematopoietic stem cells. J. Exp. Med 215, 2097–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini N, Girotra M, Naveiras O, Nikitin G, Campos V, Giger S, Roch A, Auwerx J, Lutolf MP, 2016. Specification of haematopoietic stem cell fate via modulation of mitochondrial activity. Nat. Commun 7, 13125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr MR, Passegue E, 2013. Metabolic makeover for HSCs. Cell. Stem Cell 12, 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, van der Wath RC, Blanco-Bose W, Jaworski M, Offner S, Dunant CF, Eshkind L, Bockamp E, Lio P, Macdonald HR, Trumpp A, 2008. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell 135, 1118–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WM, Liu X, Shen J, Jovanovic O, Pohl EE, Gerson SL, Finkel T, Broxmeyer HE, Qu CK, 2013. Metabolic regulation by the mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1 is required for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell. Stem Cell 12, 62–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.