Abstract

Serotonin (5-HT) was first discovered in the late 1940’s as an endogenous bioactive amine capable of inducing vasoconstriction, and in the mid-1950’s was found in the brain. It was in these early years that some of the first demonstrations were made regarding a role of brain 5-HT in neurological function and behavior, including some of the first data implicating reduced brain levels of 5-HT in clinical depression. Since that time, advances in molecular biology and physiological approaches in basic science research has intensely focused on 5-HT in the brain, and the many facets of its role during embryonic development, post-natal maturation, and neural function in adulthood continues to be established. This review focuses on what is known about the developmental roles for the 5-HT system, which we define as the neurons producing 5-HT along with pre-and post-synaptic receptors, in a vital homeostatic motor behavior - the control of breathing. We will cover what is known about the embryonic origins and fate specification of 5-HT neurons, and how the 5-HT system influences pre- and post-natal maturation of the ventilatory control system. In addition, we will focus on the role of the 5-HT system in specific respiratory behaviors during fetal, neonatal and postnatal development, and the relevance of dysfunction in this system in respiratory-related human pathologies including Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

Keywords: development, serotonin, control of breathing

Development of the 5-HT system: derivation of 5-HT neurons in embryonic life

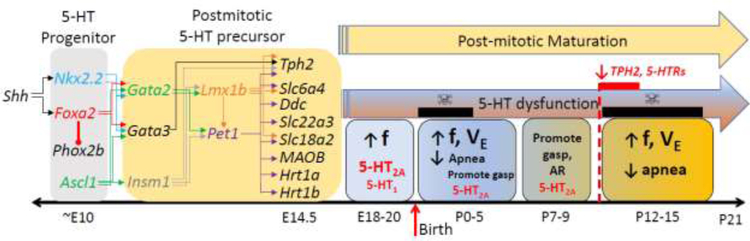

5-HT neurons arise from neuronal precursor cells in the developing mammalian neural tube, the structure formed by folds in the neural plate that ultimately transforms into the complex and complete central nervous system. What is known about the precise coordination, timing and spatial patterning of the multiple factors required for fate specification of 5-HT neurons have been reviewed (see also (Deneris and Wyler, 2012)) and are summarized in Figure 1. Neural precursor cells respond to gradients of various transcription factors including sonic hedgehog and fibroblast growth factors 4 and 8 emanating from structures such as the notochord (Gaspar et al., 2003; Goridis and Rohrer, 2002). These key signaling molecules begin to regionally pattern the epithelium of the midbrain and hindbrain and establish a dorsal-ventral axis, and specify 5-HT neuronal precursor fate in the ventral hindbrain. At this time, rostro-caudal patterning has also emerged and is arranged in segments called rhombomeres, beginning with the most rostral rhombomere (r) 1 through the most caudal r8. Some neuronal precursors in these rhombomeric segments are initially fate-specified to become either visceromotor neurons (vMNs) or 5-HT neurons depending upon the complement and temporally-regulated factors such as homeobox proteins Nkx2.2, Nkx2.9 or forkhead box A2 (Foxa2) (Briscoe et al., 1999; Pattyn et al., 2003). The switch between becoming either vMNs or 5-HT neurons depends both upon which rhombomeric segment from which they arise, but also upon the presence or absence of the transcription factor paired-like homeobox 2b (Phox2b). Animal models in which Phox2b is mutated show a gross failure to generate hindbrain vMNs, but also show ectopic r4 5-HT neuron generation (a region that does not normally give rise to 5-HT neurons) and premature generation of r2–3 and r5–8 5-HT neurons (Pattyn et al., 2000; Pattyn et al., 2003). Also important in this fate switch is Foxa2, which acts to repress vMN specification and promote 5-HT neuron neuronal fate in r1 (Jacob et al., 2007). More caudally, Phox2b initially represses Foxa2 up to embryonic day (E)10.5 before reciprocal repression by Foxa2 on Phox2b eventually gives rise to both vMNs and 5-HT neurons except in r4 (Deneris and Wyler, 2012).

Figure 1. Development and function of the 5-HT system in the prenatal and early postnatal periods.

5-HT progenitor cells require induction by Sonic hedgehog (Shh) to drive expression of transcription factors Nkx2.2 and Foxa2, the latter represses Phox2b to dictate a 5-HT neuron cell fate. Along with expression of Ascl1 around embryonic day (E)10, these transcription factors then drive coordinated expression of Gata2, Gata3, and Insm1 to ultimately drive gene expression for Lmx1b and Pet1 beginning around E11.5. The presence of these transcription factors drive coordinate expression of several post-mitotic precursor genes that derive a 5-HT neuronal “fingerprint”, including tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Tph2), the serotonin transporter (Slc6a4; 5-HTT), dopa decarboxylase (Ddc), OCT3 (Slc22a3), VMAT2 (Slc18a2), monoamine oxidase B (MAOB), and 5-HT1A (Hrt1a) and 5-HT1B (Hrt1b) receptors by E14.5. Data from a variety of animal models of central 5-HT deficiency suggest that 5-HT is critical for maintaining respiratory frequency (f) starting around E18 until the end of the first postnatal (P) week. There are two windows of postnatal development (P0–5 and P12–15) in which 5-HT is particularly important for maintaining breathing frequency (f) and overall ventilation (VE), as well as reducing apneas. Other functions include promotion of gasping during severely hypoxic conditions from birth until around P9. 5-HT2A receptors appears to be most important for these functions, although 5-HT1 receptors may have a role before birth. Rodents with 5-HT system dysfunction across the neonatal period display age-dependent respiratory phenotypes that reflect these important functions, but have two periods of vulnerability at P0–2 and P12–15 (i.e. “critical periods”; indicated by black bars with skull and crossbones). Of note, the critical period beginning at P12 coincides with a decrease in expression of a number of vital 5-HT system components (Tph2, 5-HT receptors).

5-HT neuronal precursors express several unique genetic factors, which are driven by the temporal expression of a combination additional factors, including GATA binding protein (GATA)-3 (Gata3), Insulinoma-associated 1 (Insm1), and Gata2 (reviewed in (Deneris and Wyler, 2012; Spencer and Deneris, 2017)). The precise temporal expression requisite for each of these are not yet clear, but they can drive expression of 5-HT neuronal precursor-specific transcripts including LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 beta (Lmx1b) and Pheochromocytoma 12 ETS transcription factor 1 (Pet-1; FEV in humans). Many of the genes that Lmx1b and Pet-1 control expression of embryonically are regulated by these same factors in adult 5-HT neurons, and are thus critical for the specific complement of transcriptional profiles in fate-specification and neuronal function later in life. For example, Lmx1b can drive the expression of the rate limiting enzyme in 5-HT synthesis, tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Tph2), as well as the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) and 5-HT reuptake transporter (5-HTT). In addition, Pet-1 drives coordinate expression of these same genes in addition to several others like amino acid decarboxylase, the enzyme converting 5-hydroxytryptophan into 5-HT, monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) and 5-HT (auto)receptors type 1A and 1B (Spencer and Deneris, 2017). This means that factors downstream of those in the initial fate specification (Foxa2, Achaete-scute family BHLH transcription Factor 1, Nkx2.2, and Nkx6.1) can lead to a specific genetic profile embryonically which is maintained later in adulthood in mature 5-HT neurons. Much work still needs to be done to tease out the transcriptional “cascade” of events and mechanisms that ultimately regulate 5-HT-specific neuronal gene expression, including the factors beyond autoregulation that regulate the activity of Pet1.

Relevant to the embryonic origins of 5-HT neuronal precursors is the rhombomeric segments from which they are born. Beautiful fate mapping studies has recently enlightened our understanding of this, based in large part on the work of Susan Dymecki, Patricia Jensen and others (Jensen and Dymecki, 2014; Jensen et al., 2008). These researchers exploited what is known regarding specific transcription factors expressed in the various rhombomeres in order to track which post-mitotic 5-HT neurons came from which rhombomeric segment. Utilizing this intersectional fate mapping approach, we have learned that 5-HT neurons derived from specific rhombomeres do not strictly assemble into the classically-described B nuclei as originally detailed by Dahlstom and Fuxe. Broadly, the 5-HT neurons in the rostral serotonergic nuclei in the midbrain arise from r1–3, the 5-HT neurons in the dorsal raphe nuclei arise uniquely from r1-derived precursors and median raphe 5-HT neurons arise from a combination of r1–r3 -derived precursors (Jensen et al., 2008). In addition, the 5-HT neurons populating the rostral medullary raphe (raphe magnus) largely arise from an r5-derived precursor pool, whereas the raphe pallidus and obscurus 5-HT neurons arise from r5–r8 (Bang et al., 2012).

These distinct embryonic origins of post-mitotic 5-HT neurons likely account for unique gene expression profiles of individual 5-HT neurons from distinct regions (Okaty et al., 2015), and has been shown to have a major bearing on their ultimate function in various behaviors, including breathing regulation (Brust et al., 2014). Data from previous studies suggested that caudal medullary raphe (i.e. raphe obscurus, raphe pallidus) have relatively less influence on the hypercapnic ventilatory response compared to more rostral regions (i.e. raphe magnus) (Depuy et al., 2011; Hodges et al., 2005; Mulkey et al., 2004), possibly due to an unequal distribution of pH and/or CO2-sensitive 5-HT neurons between these regions or differences in axonal projection fields. This idea was recently validated by harnessing intersectional fate mapping, in which select 5-HT neuronal populations defined by embryonic origin were silenced chemogenetically and the hypercapnic ventilatory responses queried. The authors showed convincingly that when r5-derived 5-HT neurons (or all 5-HT neurons) were silenced with clozapine-N-oxide induced (hM4Di-dependent) hyperpolarization, there was a significant suppression of the hypercapnic ventilatory response which was not apparent when other specific rhombomeric-derived lineages were inhibited (Brust et al., 2014). Furthermore, these r5-derived 5-HT neurons showed intrinsic pH/CO2 sensitivity in vitro, but this response was not found in other neighboring 5-HT neurons derived from more caudal rhombomeres. Finally, there was a distinct pattern of axonal projections emanating from the r5-derived 5-HT neurons, which selectively innervated brainstem nuclei involved in chemosensory processing but failed to innervate multiple regions rich in respiratory-related motor functions (Brust et al., 2014). Thus, it appears that embryonic origins of specific, individual 5-HT neurons determines not only their cellular “phenotype” but also their innervation pattern within the neural respiratory control network. Additional transcriptional profiling of individual 5-HT neurons that have been functionally phenotyped may provide additional, critical information regarding subpopulation-specific function of 5-HT neurons within the circuitry controlling breathing.

5-HT receptor expression during development

Target fields of 5-HT neurons, and in particular their post-synaptic receptor expression profiles across the arc of development, has a direct bearing on the overall influence of 5-HT in the cardiorespiratory control networks. With the exception of the ionotropic 5-HT3 receptor, 5-HT receptors are largely G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) and belong to 7 identified family members (5-HT1–7; reviewed in (Barnes and Sharp, 1999)). These GPCRs are linked to various G proteins, which ultimately determine the overall excitatory or inhibitory effects of 5-HT receptor activation (reviewed in (Hodges and Richerson, 2008)). Generally, 5-HT2 and 5-HT4–7 family receptors are considered “excitatory” and 5-HT1 family receptors considered “inhibitory”. This categorization is likely overly simplistic, as it depends upon the pre- and post-synaptic distribution of the 5-HT receptors and developmental stage. A full description of the molecular biology of 5-HT receptors is beyond the scope of this review, but we refer the reader to an excellent previous review that describes in detail the specific receptor agonists, antagonists, expression patterns and intracellular signaling pathways of all 5-HT receptors (Hannon and Hoyer, 2008).

Brainstem expression patterns of 5-HT receptor expression has been relatively understudied despite its major importance in determining the overall functional role(s) of 5-HT in the developing brain (Niblock et al., 2004; Panigrahy et al., 2000). Perhaps the most comprehensive studies in rodents looking at dynamic receptor expression within brainstem nuclei controlling breathing were completed by Margaret Wong-Riley and colleagues, who detailed post-natal shifts in several neurochemical systems, including 5-HT system markers, across several post-natal ages. Within the pre-Bötzinger Complex (preBӧtC), a site critical for inspiratory rhythm generation, it was noted that cytochrome oxidase activity (a marker of general neuronal activity), glutamate, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) type 2 receptors dramatically decreased in immunoreactivity from P11 to P12 in developing rat pups (Liu and Wong-Riley, 2002). Within the same region it was found that Ɣ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), GABAB and glycine receptor expression dramatically increased from P11 to P12, where the combined effects are simultaneous decreased excitation and increased inhibition. A similar abrupt reduction in CO activity was observed in multiple additional respiratory-related pre-motor and motor neuron-containing brainstem nuclei from P11–P12, suggesting there may be a global shift in the activity of the cardiorespiratory control networks during this period of development (Liu and Wong-Riley, 2003). Analyses of glutamatergic and GABAergic markers in additional nuclei indicated nearly uniform reductions and increases, respectively across a slightly broader time frame (P10–P13) (Liu and Wong-Riley, 2005, 2006).

Tph2 levels within brainstem raphe nuclei and 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors also abruptly decrease ~P12, suggesting reduced 5-HT system activity accompanies decreased glutamatergic and increased GABAergic system activity (Liu and Wong-Riley, 2008, 2010). These neurochemical changes within P10–13 correlate with increased spontaneous inhibitory post-synaptic potentials and reduced excitatory post-synaptic potentials at this same age in the rat brainstem (Gao et al., 2011). At the same developmental time point, there is decreased hypoxic ventilatory sensitivity and increased ventilatory sensitivity to inspired CO2 in rats (Davis et al., 2006). Remarkably, it appears that this developmental “signature” of 5-HT system expression changes are altered or delayed when environmental conditions are chronically changed for the first 10 days of post-natal life (Mu et al., 2018). Thus, there is anatomic and functional shifts in several markers of excitatory and inhibitory neurochemical systems, including the 5-HT system, during post-natal development that point to an inherent period of vulnerability or a “critical window” of development.

A functional role for 5-HT in respiratory control during pre-natal development

Experiments in fetal sheep provided the initial evidence that 5-HT had a stimulatory effect on fetal breathing. Later, in vitro preparations from perinatal mice and rats were used, facilitating the examination of how CNS 5-HT influenced fetal breathing (Quilligan et al., 1981), as well as the potential mechanisms involved. In the rat, respiratory rhythmogenic activity can be recorded from the C4 ventral root as early as E16.5–17 (Di Pasquale et al., 1992; Greer et al., 1992). This observation has been validated using medullary slices from fetal rats and recording from the preBӧtC (Pagliardini et al., 2003), as well as from ultrasonic recordings of rat fetal breathing movements (Kobayashi et al., 2001).

In the fetus, as in the neonate, primary excitatory drive to the preBӧtC is provided by AMPA receptor activation. With further development, respiratory network activity increases, reflected in increased frequency of fetal breathing movements and the frequency of inspiratory bursts in vitro (Greer et al., 1996; Kobayashi et al., 2001; Onimaru and Homma, 2002). Some of this increase in respiratory activity is due to network maturation (i.e. connectivity). However, developmentally-dependent alterations in the neurohumoral control of breathing also contribute. Indeed, there is a diverse array of neurochemicals that exert inhibitory (eg. GABA, opioids, prostaglandins, adenosine) or excitatory influences (e.g. progesterone, substance P (SubP), and Thyrotropin Releasing Factor (TRH)) on fetal respiratory control, and alterations in the relative contributions of these substances contributes to the changes in fetal respiratory activity with development. Either a decrease in inhibitory, or an increase in excitatory neuromodulation can increase the activity of fetal respiratory networks with development. The medullary raphe nuclei are major source of excitatory neuromodulation, providing 5-HT, SubP and TRH, all of which are capable of activating excitatory Gs and Gq pathways to stimulate fetal respiration. 5-HT immunoreactive cells first appear in the embryonic hindbrain at ~E13 in the rat, right around the time that preBӧtC neurons emerge from the ventricular zone (at E12.5–13.6) (Pagliardini et al., 2003).

The first pharmacological evidence that 5-HT has a stimulatory effect on fetal breathing came from studies done on fetal sheep in the early 1980s. Quilligan and colleagues showed that intravenous infusion of 5-hydroxytryptophan, the immediate precursor of 5-HT, increased the incidence of fetal breathing movements (Quilligan et al., 1981). Fletcher and colleagues then showed that this effect was blocked by either ketanserin or cyproheptadine, both of which are antagonists of 5-HT2 and 5-HT1 receptors (Fletcher et al., 1988). However, the specific 5-HT receptor mediating the effect remained unresolved, as both ketanserin and cyproheptadine are non-specific 5-HT receptor antagonists; ketanserin can also antagonize adrenergic alpha1 receptors while cyprohaptadine can also act as an antagonist of muscarinic receptors.

Evidence that endogenous 5-HT has a role in fetal breathing came from research using the fetal rat brainstem preparation. Di Pasquale at al. showed not only that the application of 5-HT was sufficient to increase the frequency of fictive respiratory activity in C4 and the hypoglossal rootlets isolated from E18–20 rats, but also that methysergide (a broad spectrum 5-HT receptor antagonist) reduced this activity (Di Pasquale et al., 1994), an effect that was more pronounced at E18 than at E20. Both 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) (a relatively specific 5-HT1A receptor agonist) and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI) (a specific 5-HT2A receptor agonist) were sufficient to increase fictive respiratory frequency (Di Pasquale et al., 1994), similar to the earlier work of Fletcher and colleagues (Fletcher et al., 1988), further suggesting that both receptors are involved in the effects of endogenous 5-HT on fetal breathing. Further, this group showed that fluoxetine, a serotonin reuptake inhibitor that increases the concentration of endogenous synaptic 5-HT, also increased fictive respiratory frequency (Fletcher et al., 1988). Al-Zubaidy et al. showed similar effects on hypoglossal activity using the fetal/neonatal medullary slice preparation, and that chemical stimulation of raphe obscurus (using AMPA) was sufficient to increase the frequency of hypoglossal discharge (Al-Zubaidy et al., 1996). Both effects were blocked by methysergide. These results notwithstanding, the experimental approaches used in these studies lack specificity; the antagonists used are not specific, binding both adrenergic, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Moreover, broad excitation of the raphe will elicit not only the release of 5-HT, but also SubP and TRH. More recent experiments have shown more convincingly that the excitatory effects of 5-HT on both the preBӧtC and hypoglossal motor neurons are mediated by 5-HT2 receptors (Schwarzacher et al., 2002).

5-HT may also play an important role for reducing the deleterious effects of maternal stress on fetal breathing. Recently Fournier and colleagues showed that exposing pregnant rats to predator odor from days 9 to 19 of gestation significantly increased the frequency of apneas and O2 desaturations in newborns, an effect associated with a 32% decrease in medullary 5-HT content (Fournier et al., 2013). Interestingly, the destabilizing effect of the stress on respiratory control were ameliorated following treatment with 5-HT in vitro or 8-OH-DPAT in vivo. While again these findings suggest a role for endogenous 5-HT in mitigating the destabilizing effects of stress on respiratory pattern in the fetus/newborn, more conclusive evidence is needed using animals deficient in 5-HT neurons or 5-HT, or animals in which 5-HT neurons are acutely inhibited.

5-HT controls respiratory rhythm and pattern in neonatal life: findings from in vitro studies

Some of the first studies done in this area came from Hilaire’s group who, using a neonatal brainstem-spinal cord preparation, showed that 5-HT generally has an excitatory role in breathing in the first few days of postnatal life, similar to its effects in the fetus. The addition of 5-HT or 5-HT precursors like L-tryptophan, 5-hydroxytryptophane increased fictive respiratory frequency in P0–P3 rats (Morin et al., 1991) and mice (Hilaire et al., 1997). These effects were eliminated by methysergide, a broad 5-HT antagonist, and fluoxetine, a serotonin reuptake inhibitor that increases the concentration of 5-HT in synapses. The specific receptors involved in the excitation of breathing by 5-HT seem to be species-dependent. In the rat, 5-HT acts through 5-HT1 receptors to increase fictive respiratory rhythm, while in mice 5-HT2A receptors appear to mediate the respiratory response to 5-HT. In addition, in newborn mice 5-HT has been shown to have two effects on phrenic motor neurons: a facilitatory effect on inspiratory discharge mediated by 5-HT2A receptors (Hilaire et al., 1997), and an inhibitory effect mediated by (possibly presynaptic) 5-HT1B receptors (Di Pasquale et al., 1997).

Pena and Ramirez, in keeping with findings from Hilaire’s group, showed that in neonatal mice 5-HT facilitates the respiratory rhythm (as recorded from the preBӧtC), mediated by 5-HT2A receptors. When applied to the preBӧtC, DOI stimulated fictive respiratory activity and a variety of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists reduced fictive respiratory frequency and increased the variability in the timing of inspiratory activity (Pena and Ramirez, 2002a). These data suggest not only that there is a pharmacological effect of 5-HT on neonatal breathing, but importantly that endogenous 5-HT plays a key role in facilitating and stabilizing the respiratory rhythm in early postnatal life. Pharmacological activation of protein kinase C (PKC) blocks the effect of 5-HT2A receptor antagonism on respiratory frequency, suggesting PKC activation is a key step in the signaling transduction pathways leading from 5-HT2A receptors to the downstream effector molecules (Pena and Ramirez, 2002a). Further work using the neonatal rat medullary slice and juvenile rat in situ preparation that the stimulation of inspiratory motor output is critically dependent on 5-HT and SubP originating in the raphe obscurus and acting onto the preBӧtC (Pena and Ramirez, 2004; Ptak et al., 2009). These effects are mediated via 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and NK-1 receptors, respectively. Excitatory effects of 5-HT are due in part to the modulation of the non-specific cation leak current, a current critical for the intrinsic bursting properties of preBӧtC neurons (Ptak et al., 2009). Also of interest was the identification of a reciprocal projection from the preBӧtC to the raphe which imparts a rhythmic activity in 5-HT raphe neurons (Ptak et al., 2009)

5-HT controls respiratory rhythm and pattern at specific postnatal ages: findings from in vivo studies

Since the studies by the Hilaire and Ramirez laboratories, there have been a number of studies utilizing animal models of 5-HT deficiency or excess to further delineate the role of 5-HT neurons or specifically 5-HT in the control of breathing in the early postnatal period. One of the earliest was a study by Bou-Flores and colleagues who used a transgenic mouse line deficient in MAOA, the enzyme catalyzing the breakdown of 5-HT into 5-hydroxy-3-indole acetic acid, and therefore have higher brainstem concentrations of 5-HT from early embryogenesis onwards (Bou-Flores et al., 2000). Their main finding is that the MAOA-deficient pups exhibited destabilized breathing in the neonatal period, an effect that was mimicked by treating control animals prenatally with DOI (Burnet et al., 2001). Associated with this phenotype was an abnormal morphology of phrenic motor neurons, indicating that 5-HT has an important developmental role for these neurons.

More recent studies have examined how a loss of 5-HT neurons, or a specific loss of 5-HT within the CNS, affects the control of breathing (including ventilatory chemoreflexes) in the neonatal period. Investigators have either used pharmacological approaches to lesion 5-HT neurons to reduce their 5-HT content (e.g. using 5-HT-specific neurotoxins or inhibitors), or have tested animals with a genetically-induced loss of 5-HT neurons. A major factor in the interpretation of the data obtained using these two approaches is the degree to which the 5-HT system is depleted of neurons and/or 5-HT content, as well as the amount of time the animals are deficient in 5-HT prior to testing. Nattie’s group first used neonatal piglets in which 5-HT neurons within the caudal raphe nuclei were either focally inhibited (using 8-OH-DPAT, an agonist of 5-HT1A receptors that reduce the activity of 5-HT neurons) or lesioned (using the 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (5,7-DHT), a 5-HT neurotoxin). Messier et al. found that focal inhibition of medullary 5-HT neurons with 8-OH-DPAT had no significant effects on room air breathing (Messier et al., 2004). However, the treatment altered the ventilatory response to increasing CO2 (the CO2 chemoreflex) in an age-dependent fashion: in the youngest piglets (postnatal day (P)3-P6), 8-OH-DPAT actually increased the ventilatory response to CO2, while in older piglets (P7-P16) the treatment reduced the CO2 response. Cummings and colleagues also applied 5,7-DHT to the brainstem of newborn rat pups, causing an ~80% loss of 5-HT neurons from the caudal raphe, testing them at P5–6 and 10–12. The loss of 5-HT neurons led to decreased respiratory frequency and overall ventilation at P5–6 – in keeping with the role of 5-HT prenatally - but not at P10–12. This suggests that with development, compensation from other neuromodulator systems restores normal respiratory frequency and overall ventilation. That said, although the frequency of breathing was normalized by P10–12, 5,7-DHT-treated pups had more frequent spontaneous apneas at this age than their untreated counterparts, suggesting that 5-HT neurons are also necessary in the 2nd postnatal week for maintaining respiratory stability (Cummings et al., 2009).

In addition to approaches involving pharmacological lesioning of 5-HT neurons, later experiments utilized neonatal mouse and rat models deficient in key transcription factors necessary for the proper development of 5-HT neurons. Mice in which Lmx1b is specifically lost in Pet-1-expressing neurons are nearly completely devoid of 5-HT neurons (Zhao et al., 2006). In the first few days of life these mice display profound apnea (occasionally 30 sec long!) and markedly reduced ventilation (Hodges et al., 2009). This phenotype resolves with development, with no secondary manifestation later in neonatal period. Pet-1 is an ETS domain transcription factor that is critical for the proper expression of genes specific to 5-HT neurons; namely, tryptophan hydroxylase 2, the rate limiting enzyme in 5-HT biosynthesis, and the 5-HTT (Hendricks et al., 1999; Kiyasova and Gaspar, 2011) Pet-1−/− mice, lacking about ~70% of their brainstem 5-HT neurons, also have reduced respiratory frequency and prolonged apneas in the first postnatal week (similar to 5,7-DHT-treated rat pups) (Erickson et al., 2007). Interestingly these respiratory phenotypes, unlike those described in Pet-1-conditional Lmx1b−/− mice, reappear at P14–15, with evidence of subsequent hypoxemia only at this age (Cummings et al., 2010). Together, results from these studies using the Pet-1−/− and Lmx1b conditional knockout mice support the earlier work from the Ramirez and Hilaire laboratories indicating a crucial role for 5-HT in the facilitation of respiratory rhythm and stabilization of the respiratory pattern in the neonatal period. An additional intriguing possibility is that the function of 5-HT neurons changes over the course of neonatal life – it may be that there are specific developmental time points when the 5-HT is especially critical for respiratory control. Respiratory control defects that emerge towards the end of the 2nd postnatal week in rodents may be especially relevant clinically given that key brain stem loci at this age may be similar to a ~2 month old human with respect to development (Clancy et al., 2001).

Given the nature of the models – i.e. a loss of the 5-HT neurons and hence all co-released neuromodulators, it remained possible that a loss of SubP and TRH neuromodulation contributes to the respiratory phenotypes of neonatal Pet-1 null and conditional Lmx1b−/− mice. In an attempt to answer this question, experiments were subsequently performed on mouse and rat pups deficient in the gene encoding tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Tph2−/−), the enzyme catalyzing the rate-limiting step in 5-HT biosynthesis, the hydroxylation of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan. Neonatal Tph2−/− mice have reduced respiratory frequency and destabilized breathing throughout the first two postnatal weeks (Cummings et al., 2011c). Interestingly however, these animals appear to compensate with an increased tidal volume to preserve overall ventilation (Chen et al., 2013). Kaplan and colleagues also recently examined the control of breathing in Tph2−/− rat pups throughout the early postnatal period. Similar to Pet-1 null and conditional Lmx1b null mice, Tph2−/− rats have increased apnea and reduced respiratory frequency and overall ventilation in the first few days of life (Kaplan et al., 2016). Similar to Pet-1−/− mice, the reduced frequency and increased apnea re-emerge in the second postnatal week of life (Kaplan et al., 2016; Young et al., 2017). Systemic injection of 5-hydroxytryptophan over 12hr was sufficient to restore the respiratory frequency and ventilation of ~2 week-old Tph2−/− rats, suggesting that their compromised breathing is unlikely due to secondary, developmental abnormalities related to 5-HT deficiency. The apneas demonstrated by Tph2−/− rats occur during prolonged episodes of active sleep, and are absent during quiet sleep (Young et al., 2017). And there is new evidence that this phenotype is associated with increased cholinergic drive (Davis et al., 2019). These findings raise the possibility that 5-HT neurons – possibly those in the dorsal raphe that reside close to pontine, “active sleep-driving” cholinergic neurons – exert a “braking” effect on the cholinergic drive to respiratory patterning neurons during active sleep. This idea requires further testing, however.

Taken together, these studies clearly demonstrate that a specific loss of 5-HT from the CNS compromises respiratory rhythm and pattern, and again suggest that there are specific points in postnatal development (i.e. first few days and around 2 weeks of age) when the effects of 5-HT deficiency on breathing are particularly deleterious. Interestingly they also hint at an important interaction between the serotonergic and cholinergic systems in the control of respiratory patterning in active sleep; this may be relevant to our understanding of pathologies related to 5-HT deficiency that manifest only during periods of sleep (e.g. Sudden infant Death Syndrome; see below). Finally, more work needs to be done with respect to the role of 5-HT (or 5-HT neurons) in the developing hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory chemoreflexes, which themselves undergo maturation across postnatal development in mammals.

5-HT is critical for proper gasping and the coordinated cardiorespiratory response to severe hypoxia (autoresuscitation)

Experiments by several investigators using an array of animal models of 5-HT system dysfunction strongly suggest that 5-HT helps to prevent apnea and potentially hypoxemia in the second postnatal week of life. The question arose as to whether 5-HT had any influence on the coordinated cardiovascular and respiratory response to severe hypoxia (i.e. autoresuscitation). The primary respiratory component of autoresuscitation is gasping, a low-frequency, high-volume respiratory behavior that emerges when brainstem tissue PO2 falls below ~10 mmHg, as it might during prolonged apnea. In such instances, the severe hypoxic stress suppresses heart rate and blood pressure, where gasping is necessary to quickly increase gas exchange to relieve the inhibition on cardiovascular function. Coupled with the increase in heart rate and blood pressure, gasping effectively increases tissue PO2 which eventually re-establishes a eupneic pattern of breathing if autoresuscitation is successful.

Early studies examining the role of 5-HT in gasping came from Ramirez’s group who had used the in vitro medullary slice preparation to characterize two types of pacemaker neurons – cadmium sensitive and cadmium insensitive (i.e. persistent sodium current-dependent) – and their contribution to fictive eupnea and gasping (Pena and Ramirez, 2002b). They found that only cadmium insensitive pacemakers – those that are necessary for fictive gasping – require endogenous 5-HT2A receptor activation for bursting (Pena and Ramirez, 2002b). Later, with recordings made from the ventral respiratory group they showed that indeed fictive gasping, but not fictive eupnea, was eliminated by 5-HT2A receptor blockers (Tryba et al., 2006).

The idea that 5-HT is necessary for the genesis of gasping was put into question following subsequent studies by St-John, Leiter and colleagues. Using the in situ perfused juvenile rat preparation, these investigators showed that 5-HT2A blockade had little to no effect on gasp generation (there was a modest effect on the maintenance of gasping, once generated) (St-John and Leiter, 2008; Toppin et al., 2007). This group later showed that gasping was normal in juvenile Pet-1 knockout mice that lack ~70% of their 5-HT neurons (St-John et al., 2009). What could explain the disparate findings between the findings of Ramirez and colleagues and those from St-John and Leiter? An obvious possibility is that brainstem slices from neonates behave differently because they are isolated and thus potentially not under the influence of the entire array of endogenous neuromodulators. However, more recent studies strongly support the idea that the role of 5-HT in gasping changes over the course of development. For example, recapitulating findings of Ramirez and colleagues from neonatal brain stem slices, as neonates Pet-1 knockout mice are compromised in their ability to generate gasping (i.e. hypoxic apnea is severely prolonged) (Cummings et al., 2011a; Erickson and Sposato, 2009), a phenotype associated with a severe delay in the subsequent recovery of heart rate and eupnea. And in parallel with its role in preventing apnea, 5-HT may facilitate gasping only at critical periods of neonatal life. Data from the study by Cummings and colleagues suggest that this period falls around the beginning of the 2nd postnatal week; towards the end of the 2nd postnatal week, Pet-1 knockout mice displayed normal gasping, suggesting compensation by other neuromodulators at this developmental stage (Cummings et al., 2011a).

The findings of the Ramirez group notwithstanding, at issue was whether the defective gasping displayed by Pet-1 knockout was related to altered development within the neuronal circuitry governing gasping (these animals lack 5-HT during embryogenesis), or instead was the result of an acute physiological loss of 5-HT within these circuits. Several lines of experiments suggest the latter. First, rat pups in which 5-HT neurons are lesioned postnatally also have delayed gasping (Cummings et al., 2011b). Second, acute restoration of CNS 5-HT via 5-hydroxytryptophan supplementation re-established normal gasping in Tph2−/− mice (Chen et al., 2013). Last, and perhaps most convincing, acute silencing of Pet-1-expressing neurons through the activation of foreign inhibitory receptors (i.e. using Designer Receptor Exclusively Activated by Designer Drug (DREAD) technologies), also delayed gasping (Dosumu-Johnson et al., 2018). From this work we can reasonably conclude that the genesis of gasping in the early postnatal period (but not at older ages) is critically dependent on 5-HT, likely acting through 5-HT2A receptors.

Relevance of developing 5-HT system function to human pathologies

Multiple aspects of the 5-HT system, including fate-specification and differentiation of 5-HT neurons, 5-HT receptor expression, etc., begin developing early in embryogenesis and continue to mature pre- and post-natally. Key transitions immediately after birth and around 2 weeks post-natal in rodents occur in the neural circuitry that governs respiratory control, during which time the system appears most critically influenced by 5-HT. While the equivalent post-natal ages in human infants are not certain, there are data to suggest critical developmental stages with respect to vital control systems including breathing control in human infants and 5-HT system dysfunction. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), is defined as the unexpected death of an infant 1–12 months of age for which no cause of death can be determined after autopsy and death scene investigation. SIDS, occurring during periods of sleep, has a clear peak incidence between 2–4 months of age, highly suggestive of a developmental “window” of susceptibility. While the pathophysiology that leads to unanticipated death remains unclear, several prospective studies indicate that some future SIDS cases, similar to animals lacking 5-HT, experience more obstructive and central sleep apnea than case controls (Kahn et al., 1988; Kato et al., 2001) as well as failed autoresuscitation before death (Poets et al., 1999; Sridhar et al., 2003). In addition, studies in human autopsy tissues strongly implicate 5-HT system dysfunction in the cascade of events culminating in death (Duncan et al., 2010; Paterson et al., 2006). These observations strongly suggest that underlying biological dysfunction (e.g. 5-HT system defects) may combine with an exogenous stressor (e.g. prone sleeping position) during a critical developmental stage for maturation of control systems to ultimately cause SIDS in humans. Future studies that clearly define the mechanisms by which 5-HT system defects lead to apnea and compromised autoresuscitation in the early postnatal period – particularly mechanisms that involve sleep – would be a critical advancement for efforts aimed at developing a priori risk assessment and prevention strategies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Al-Zubaidy ZA, Erickson RL, Greer JJ, 1996. Serotonergic and noradrenergic effects on respiratory neural discharge in the medullary slice preparation of neonatal rats. Pflugers Arch 431, 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang SJ, Jensen P, Dymecki SM, Commons KG, 2012. Projections and interconnections of genetically defined serotonin neurons in mice. Eur J Neurosci 35, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes NM, Sharp T, 1999. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 38, 1083–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou-Flores C, Lajard AM, Monteau R, De ME, Seif I, Lanoir J, Hilaire G, 2000. Abnormal phrenic motoneuron activity and morphology in neonatal monoamine oxidase A-deficient transgenic mice: possible role of a serotonin excess. J.Neurosci 20, 4646–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Sussel L, Serup P, Hartigan-O’Connor D, Jessell TM, Rubenstein JL, Ericson J, 1999. Homeobox gene Nkx2.2 and specification of neuronal identity by graded Sonic hedgehog signalling. Nature 398, 622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust RD, Corcoran AE, Richerson GB, Nattie E, Dymecki SM, 2014. Functional and developmental identification of a molecular subtype of brain serotonergic neuron specialized to regulate breathing dynamics. Cell reports 9, 2152–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnet H, Bevengut M, Chakri F, Bou-Flores C, Coulon P, Gaytan S, Pasaro R, Hilaire G, 2001. Altered respiratory activity and respiratory regulations in adult monoamine oxidase A-deficient mice. J.Neurosci 21, 5212–5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Magnusson J, Karsenty G, Cummings KJ, 2013. Time- and age-dependent effects of serotonin on gasping and autoresuscitation in neonatal mice. J Appl Physiol 114, 1668–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finlay BL, 2001. Translating developmental time across mammalian species. Neuroscience 105, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Commons KG, Fan KC, Li A, Nattie EE, 2009. Severe spontaneous bradycardia associated with respiratory disruptions in rat pups with fewer brain stem 5-HT neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296, R1783–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Commons KG, Hewitt JC, Daubenspeck JA, Li A, Kinney HC, Nattie EE, 2011a. Failed heart rate recovery at a critical age in 5-HT-deficient mice exposed to episodic anoxia: implications for SIDS. J Appl Physiol 111, 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Hewitt JC, Li A, Daubenspeck JA, Nattie EE, 2011b. Postnatal loss of brainstem serotonin neurones compromises the ability of neonatal rats to survive episodic severe hypoxia. J Physiol 589, 5247–5256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Li A, Deneris ES, Nattie EE, 2010. Bradycardia in serotonin-deficient Pet-1−/− mice: influence of respiratory dysfunction and hyperthermia over the first 2 postnatal weeks. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298, R1333–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Li A, Nattie EE, 2011c. Brainstem serotonin deficiency in the neonatal period: autonomic dysregulation during mild cold stress. J Physiol 589, 2055–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MR, Magnusson JL, Cummings KJ, 2019. Increased central cholinergic drive contributes to the apneas of serotonin-deficient rat pups during active sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Davis SE, Solhied G, Castillo M, Dwinell M, Brozoski D, Forster HV, 2006. Postnatal developmental changes in CO2 sensitivity in rats. J.Appl.Physiol 101, 1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneris ES, Wyler SC, 2012. Serotonergic transcriptional networks and potential importance to mental health. Nat Neurosci 15, 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuy SD, Kanbar R, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG, 2011. Control of breathing by raphe obscurus serotonergic neurons in mice. J Neurosci 31, 1981–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasquale E, Lindsay A, Feldman J, Monteau R, Hilaire G, 1997. Serotonergic inhibition of phrenic motoneuron activity: an in vitro study in neonatal rat. Neurosci.Lett 230, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasquale E, Monteau R, Hilaire G, 1992. In vitro study of central respiratory-like activity of the fetal rat. Exp Brain Res 89, 459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasquale E, Monteau R, Hilaire G, 1994. Endogenous serotonin modulates the fetal respiratory rhythm: an in vitro study in the rat. Brain Res.Dev.Brain Res 80, 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosumu-Johnson RT, Cocoran AE, Chang Y, Nattie E, Dymecki SM, 2018. Acute perturbation of Pet1-neuron activity in neonatal mice impairs cardiorespiratory homeostatic recovery. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JR, Paterson DS, Hoffman JM, Mokler DJ, Borenstein NS, Belliveau RA, Krous HF, Haas EA, Stanley C, Nattie EE, Trachtenberg FL, Kinney HC, 2010. Brainstem serotonergic deficiency in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 303, 430–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JT, Shafer G, Rossetti MD, Wilson CG, Deneris ES, 2007. Arrest of 5HT neuron differentiation delays respiratory maturation and impairs neonatal homeostatic responses to environmental challenges. Respir.Physiol Neurobiol 159, 85–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JT, Sposato BC, 2009. Autoresuscitation responses to hypoxia-induced apnea are delayed in newborn 5-HT-deficient Pet-1 homozygous mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 106, 1785–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher DJ, Hanson MA, Moore PJ, Nijhuis JG, Parkes MJ, 1988. Stimulation of breathing movements by L-5-hydroxytryptophan in fetal sheep during normoxia and hypoxia. J Physiol 404, 575–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S, Steele S, Julien C, Fournier S, Gulemetova R, Caravagna C, Soliz J, Bairam A, Kinkead R, 2013. Gestational stress promotes pathological apneas and sex-specific disruption of respiratory control development in newborn rat. J Neurosci 33, 563–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XP, Liu QS, Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2011. Excitatory-inhibitory imbalance in hypoglossal neurons during the critical period of postnatal development in the rat. J Physiol 589, 1991–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Cases O, Maroteaux L, 2003. The developmental role of serotonin: news from mouse molecular genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci 4, 1002–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goridis C, Rohrer H, 2002. Specification of catecholaminergic and serotonergic neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 3, 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Carter JE, Allan DW, 1996. Respiratory rhythm generation in a precocial rodent in vitro preparation. Respir Physiol 103, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Smith JC, Feldman JL, 1992. Respiratory and locomotor patterns generated in the fetal rat brain stem-spinal cord in vitro. J Neurophysiol 67, 996–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J, Hoyer D, 2008. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav Brain Res 195, 198–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks T, Francis N, Fyodorov D, Deneris ES, 1999. The ETS domain factor Pet-1 is an early and precise marker of central serotonin neurons and interacts with a conserved element in serotonergic genes. J Neurosci 19, 10348–10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilaire G, Bou C, Monteau R, 1997. Serotonergic modulation of central respiratory activity in the neonatal mouse: an in vitro study. Eur J Pharmacol 329, 115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Opansky C, Qian B, Davis S, Bonis JM, Krause K, Pan LG, Forster HV, 2005. Carotid body denervation alters ventilatory responses to ibotenic acid injections or focal acidosis in the medullary raphe. J.Appl.Physiol 98, 1234–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Richerson GB, 2008. Contributions of 5-HT neurons to respiratory control: Neuromodulatory and trophic effects. Respir.Physiol Neurobiol 164, 222–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Wehner M, Aungst J, Smith JC, Richerson GB, 2009. Transgenic mice lacking serotonin neurons have severe apnea and high mortality during development. J Neurosci 29, 10341–10349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Ferri AL, Milton C, Prin F, Pla P, Lin W, Gavalas A, Ang SL, Briscoe J, 2007. Transcriptional repression coordinates the temporal switch from motor to serotonergic neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 10, 1433–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Dymecki SM, 2014. Essentials of recombinase-based genetic fate mapping in mice. Methods Mol Biol 1092, 437–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Scott MM, Deneris ES, Dymecki SM, 2008. Redefining the serotonergic system by genetic lineage. Nat Neurosci 11, 417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn A, Blum D, Rebuffat E, Sottiaux M, Levitt J, Bochner A, Alexander M, Grosswasser J, Muller MF, 1988. Polysomnographic studies of infants who subsequently died of sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics 82, 721–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan K, Echert AE, Massat B, Puissant MM, Palygin O, Geurts AM, Hodges MR, 2016. Chronic central serotonin depletion attenuates ventilation and body temperature in young but not adult Tph2 knockout rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120, 1070–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato I, Groswasser J, Franco P, Scaillet S, Kelmanson I, Togari H, Kahn A, 2001. Developmental characteristics of apnea in infants who succumb to sudden infant death syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164, 1464–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyasova V, Gaspar P, 2011. Development of raphe serotonin neurons from specification to guidance. Eur J Neurosci 34, 1553–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Lemke RP, Greer JJ, 2001. Ultrasound measurements of fetal breathing movements in the rat. J Appl Physiol (1985) 91, 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2002. Postnatal expression of neurotransmitters, receptors, and cytochrome oxidase in the rat pre-Botzinger complex. J Appl Physiol 92, 923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2003. Postnatal changes in cytochrome oxidase expressions in brain stem nuclei of rats: implications for sensitive periods. J Appl Physiol 95, 2285–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2005. Postnatal developmental expressions of neurotransmitters and receptors in various brain stem nuclei of rats. J Appl Physiol 98, 1442–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2006. Developmental changes in the expression of GABAA receptor subunits alpha1, alpha2, and alpha3 in brain stem nuclei of rats. Brain Res 1098, 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2008. Postnatal changes in the expression of serotonin 2A receptors in various brain stem nuclei of the rat. J Appl Physiol 104, 1801–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT, 2010. Postnatal changes in tryptophan hydroxylase and serotonin transporter immunoreactivity in multiple brainstem nuclei of the rat: implications for a sensitive period. J Comp Neurol 518, 1082–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier ML, Li A, Nattie EE, 2004. Inhibition of medullary raphe serotonergic neurons has age-dependent effects on the CO2 response in newborn piglets. J.Appl.Physiol 96, 1909–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin D, Monteau R, Hilaire G, 1991. 5-Hydroxytryptamine modulates central respiratory activity in the newborn rat: an in vitro study. Eur J Pharmacol 192, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu L, Xia DD, Michalkiewicz T, Hodges M, Mouradian G, Konduri GG, Wong-Riley MTT, 2018. Effects of neonatal hyperoxia on the critical period of postnatal development of neurochemical expressions in brain stem respiratory-related nuclei in the rat. Physiol Rep 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG, 2004. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci 7, 1360–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niblock MM, Kinney HC, Luce CJ, Belliveau RA, Filiano JJ, 2004. The development of the medullary serotonergic system in the piglet. Auton Neurosci 110, 65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaty BW, Freret ME, Rood BD, Brust RD, Hennessy ML, deBairos D, Kim JC, Cook MN, Dymecki SM, 2015. Multi-Scale Molecular Deconstruction of the Serotonin Neuron System. Neuron 88, 774–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Homma I, 2002. Development of the rat respiratory neuron network during the late fetal period. Neurosci Res 42, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliardini S, Ren J, Greer JJ, 2003. Ontogeny of the pre-Botzinger complex in perinatal rats. J Neurosci 23, 9575–9584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahy A, Filiano J, Sleeper LA, Mandell F, Valdes-Dapena M, Krous HF, Rava LA, Foley E, White WF, Kinney HC, 2000. Decreased serotonergic receptor binding in rhombic lip-derived regions of the medulla oblongata in the sudden infant death syndrome. J.Neuropathol.Exp.Neurol 59, 377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DS, Trachtenberg FL, Thompson EG, Belliveau RA, Beggs AH, Darnall R, Chadwick AE, Krous HF, Kinney HC, 2006. Multiple serotonergic brainstem abnormalities in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 296, 2124–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Hirsch M, Goridis C, Brunet JF, 2000. Control of hindbrain motor neuron differentiation by the homeobox gene Phox2b. Development 127, 1349–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Vallstedt A, Dias JM, Samad OA, Krumlauf R, Rijli FM, Brunet JF, Ericson J, 2003. Coordinated temporal and spatial control of motor neuron and serotonergic neuron generation from a common pool of CNS progenitors. Genes & development 17, 729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena F, Ramirez JM, 2002a. Endogenous activation of serotonin-2A receptors is required for respiratory rhythm generation in vitro. J Neurosci 22, 11055–11064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena F, Ramirez JM, 2002b. Endogenous activation of serotonin-2A receptors is required for respiratory rhythm generation in vitro. J.Neurosci 22, 11055–11064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena F, Ramirez JM, 2004. Substance P-mediated modulation of pacemaker properties in the mammalian respiratory network. J.Neurosci 24, 7549–7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poets CF, Meny RG, Chobanian MR, Bonofiglo RE, 1999. Gasping and other cardiorespiratory patterns during sudden infant deaths. Pediatr.Res 45, 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptak K, Yamanishi T, Aungst J, Milescu LS, Zhang R, Richerson GB, Smith JC, 2009. Raphe neurons stimulate respiratory circuit activity by multiple mechanisms via endogenously released serotonin and substance P. J.Neurosci [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Quilligan EJ, Clewlow F, Johnston BM, Walker DW, 1981. Effect of 5-hydroxytryptophan on electrocortical activity and breathing movements of fetal sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 141, 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzacher SW, Pestean A, Gunther S, Ballanyi K, 2002. Serotonergic modulation of respiratory motoneurons and interneurons in brainstem slices of perinatal rats. Neuroscience 115, 1247–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer WC, Deneris ES, 2017. Regulatory Mechanisms Controlling Maturation of Serotonin Neuron Identity and Function. Front Cell Neurosci 11, 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar R, Thach BT, Kelly DH, Henslee JA, 2003. Characterization of successful and failed autoresuscitation in human infants, including those dying of SIDS. Pediatr.Pulmonol 36, 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-John WM, Leiter JC, 2008. Maintenance of gasping and restoration of eupnea after hypoxia is impaired following blockers of alpha1-adrenergic receptors and serotonin 5-HT2 receptors. J Appl Physiol (1985) 104, 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-John WM, Li A, Leiter JC, 2009. Genesis of gasping is independent of levels of serotonin in the Pet-1 knockout mouse. J.Appl.Physiol 107, 679–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppin VA, Harris MB, Kober AM, Leiter JC, St-John WM, 2007. Persistence of eupnea and gasping following blockade of both serotonin type 1 and 2 receptors in the in situ juvenile rat preparation. J.Appl.Physiol 103, 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryba AK, Pena F, Ramirez JM, 2006. Gasping activity in vitro: a rhythm dependent on 5-HT2A receptors. J.Neurosci 26, 2623–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JO, Geurts A, Hodges MR, Cummings KJ, 2017. Active sleep unmasks apnea and delayed arousal in infant rat pups lacking central serotonin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 123, 825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZQ, Scott M, Chiechio S, Wang JS, Renner KJ, Gereau RW, Johnson RL, Deneris ES, Chen ZF, 2006. Lmx1b is required for maintenance of central serotonergic neurons and mice lacking central serotonergic system exhibit normal locomotor activity. J.Neurosci 26, 12781–12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]