This cohort study investigates the association of bulimia nervosa with the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality among women hospitalized for bulimia compared with those hospitalized for pregnancy-related events in Quebec, Canada from 2006 to 2018.

Key Points

Question

Is bulimia nervosa associated with a long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality among women?

Findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of 416 709 women in Canada (including 818 women hospitalized for bulimia nervosa and 415 891 for pregnancy-related events) who were followed up for 12 years, women with a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa had a significantly increased risk of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease and death up to 8 years after the index bulimia-related hospitalization.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa may benefit from closer management of this condition for prevention of cardiovascular risk factors and disease.

Abstract

Importance

Bulimia nervosa is associated with short-term cardiovascular complications in women, but its long-term consequences on cardiovascular health are unknown.

Objective

To study the association of bulimia nervosa with the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in women.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this longitudinal cohort study, 416 709 women hospitalized in Quebec, Canada, including women hospitalized for bulimia nervosa and those for pregnancy-related events as a comparison group, were followed up for 12 years from 2006 to 2018 to identify incidences of cardiovascular disease and death.

Exposures

At least 1 hospitalization for bulimia nervosa.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The study participants were followed up to identify future incidences of cardiovascular disease and deaths. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs to assess the association of bulimia nervosa with future outcomes after adjustment for patient characteristics.

Results

The study population comprised 818 women who were hospitalized for bulimia nervosa (mean [SD] age, 28.3 [13.4] years) and 415 891 hospitalized for pregnancy-related events (mean [SD] age, 28.3 [5.4] years). Patients were followed up for a total of 2 957 677 person-years. The women hospitalized for bulimia nervosa had a greater incidence of cardiovascular disease compared with those hospitalized for pregnancy-related events (10.34 [95% CI, 7.77-13.76] vs 1.02 [95% CI, 0.99-1.06] per 1000 person-years). Incidence of future cardiovascular disease was even higher for women with 3 or more bulimia admissions (25.13 [95% CI, 13.52-46.70] per 1000 person-years). Women hospitalized for bulimia nervosa had 4.25 (95% CI, 2.98-6.07) times the risk of any cardiovascular disease and 4.72 (95% CI, 2.05-10.84) times the risk of death compared with women hospitalized for pregnancy-related events. Bulimia nervosa was found to be associated with ischemic heart disease (HR, 6.63; 95% CI, 3.34-13.13), atherosclerosis (HR, 6.94; 95% CI, 3.08-15.66), and cardiac conduction defects (HR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.57-5.71). Bulimia was also associated with 21.93 (95% CI, 9.29-51.74) times the risk of myocardial infarction at 2 years of follow-up and 14.13 (95% CI, 6.02-33.18) times the risk at 5 years of follow-up.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that bulimia nervosa may be associated with the long-term risk of any cardiovascular disease, such as ischemic cardiac events and conduction disorders, as well as with death among women. The findings also suggest that women with a history of bulimia nervosa should be screened regularly for ischemic cardiovascular disease and may benefit from prevention of and treatment for cardiovascular risk factors.

Introduction

Bulimia nervosa has a lifetime prevalence of 1.5% and is one of the most common psychiatric diseases in women.1 Despite a large body of evidence supporting a connection between mental health and later cardiovascular disease,2 little is known about the association of bulimia nervosa with long-term cardiovascular morbidity.3 Because cardiovascular disease is responsible for nearly a quarter of the deaths among women,4 understanding the contribution of bulimia nervosa may be critical to prevention and surveillance efforts.

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory purging, including self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives, excessive exercise, or restricted oral intake, behaviors that have the potential to affect cardiovascular stability.1 In addition to immediate complications, such as oropharyngeal and gastrointestinal disorders, vomiting and use of laxatives can result in electrolyte imbalance and an increased short-term risk of arrhythmias.5 Damage to cardiac myocytes may also occur and lead to congestive heart failure, ventricular arrhythmia, or sudden cardiac death.5 Moreover, bulimia is associated with psychosocial stress and anxiety, which are additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease and death.1,2,6,7 Bulimia nervosa, therefore, has the potential to have a long-term association with the development of cardiovascular disease. We designed a study to assess the association between bulimia nervosa and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality during 12 years of follow-up in a large cohort of women.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We carried out a longitudinal cohort study using the Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele registry from Quebec, Canada.8 The registry includes discharge abstracts of all hospitalizations in Quebec and contains up to 41 diagnostic codes and 35 procedure codes for each admission. The robustness of the data has been demonstrated.9 We identified women who were hospitalized for bulimia nervosa between 2006 and 2016 in Quebec. In addition, we identified a comparison group comprising women who were hospitalized for a pregnancy-related event, including delivery of a live or stillborn infant, abortion, ectopic pregnancy, or formation of a hydatidiform mole during the same period. The comparison group was representative of most women in the province because 99% of deliveries and a significant proportion of other pregnancy events occur in hospitals. We did not include women who were never pregnant, a group that may be less suitable for comparison owing to a higher baseline risk of chronic disease.10

We began following up the women at their first (index) admission and ended follow-up at the first incidence of cardiovascular disease, death, or the end of the study on March 31, 2018, whichever occurred first. Women with invalid health insurance numbers were not eligible for the study because we could not track them over time. We did not include women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa or preexisting cardiovascular disease at cohort entry, including any of the outcomes under study.

Bulimia Nervosa

In this study, we used codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (codes F50.2 and F50.3) to identify women with bulimia nervosa (N = 818). We categorized bulimia as a binary exposure (yes, no). We also identified the total number of admissions for bulimia during the study period (0, 1, 2, or ≥3 admissions). The data allowed us to identify women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa severe enough to require hospitalization. Women diagnosed with bulimia may be hospitalized for reasons ranging from electrolyte imbalance5 and gastrointestinal and pulmonary complications5 to psychiatric disorders, including suicide attempt.11 This study complied with Tri-Council Policy requirements for research in Canada. The institutional review board of the University of Montreal Hospital Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, determined that informed consent was not needed as data were anonymized and waived the ethics review.

Outcomes

We used diagnostic codes in the ICD-10 and intervention codes in the Canadian Classification of Health Interventions12 to identify cardiovascular disease (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Outcomes included myocardial infarction, other ischemic heart disease, conduction disorders, pulmonary vascular disease (pulmonary embolism, other pulmonary disorders), cerebrovascular disease (ischemic stroke, cerebrovascular hemorrhage, and other cerebrovascular disease), atherosclerosis, and coronary care unit admission. We also analyzed angina, cardiac arrest, inflammatory heart disease, valve disorders, cardiomyopathy, heart procedures (coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass graft, valve surgery, pacemaker, cardiac transplant, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and open heart resuscitation), and vessel procedures (angiography, aorta surgery, and intracranial surgery) as a composite variable (yes, no). The number of individual events was too low to allow us to analyze these disorders separately. We analyzed all-cause mortality during hospitalization as a secondary outcome.

Covariates

We accounted for several covariates that could confound the association between bulimia and cardiovascular disease, including age at cohort entry as a continuous variable in quadratic splines13; preexisting comorbidity, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcohol, tobacco, or substance use (yes, no)1,14; socioeconomic deprivation measured by quintile of neighborhood income, educational level, and employment (most socioeconomically disadvantaged, not disadvantaged, or unknown)15; rurality (yes, no, or unknown); and time period (2006-2008, 2009-2012, or 2013-2016). These covariates are associated with both bulimia nervosa and cardiovascular disorders in the existing literature.1,14 eTable 2 in the Supplement provides diagnostic and intervention codes for comorbidities.

Statistical Analysis

We computed incidence rates of cardiovascular disease and death per 1000 person-years. We used the cumulative incidence function to plot incidence rates for cardiovascular outcomes over time.16 The cumulative incidence function treats death as a competing event.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to compute unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for estimating the association of bulimia with future cardiovascular disease. Hazard ratios reflect the ratio of the risk of cardiovascular disease and death in women diagnosed with bulimia relative to that in women without bulimia during a specific time interval. In adjusted models, we accounted for age at first admission, preexisting comorbidity, socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, and period. We defined the time scale as the number of days since cohort entry and censored women who did not develop a cardiovascular outcome before the end of the study. For cardiovascular disease, we applied the Fine and Gray method to account for death as a competing event.17 We verified the proportionality of hazards using log (negative log survival) plots.

Next, we tested the possibility that the association between bulimia nervosa and cardiovascular disease or death changed during follow-up. To do so, we included a quadratic interaction term between time and bulimia nervosa in adjusted regression models. We subsequently computed HRs and 95% CIs for each year of follow-up and plotted the associations over time.

We performed several sensitivity analyses. We stratified women diagnosed with bulimia according to gravidity and ran the analysis using age 10 years as the start time to assess whether a different entry time altered the results. We also restricted the analysis to women who entered the cohort before 2013, when diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa changed from purging twice a week to once a week for at least 3 months,18 to assess the association with the stricter diagnostic criteria earlier in the study.

We performed the analyses in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). We used 2-sided hypothesis tests and assessed statistical significance with 95% CIs.

Results

The study participants included 416 709 women (including 818 women hospitalized for bulimia nervosa and 415 891 for pregnancy-related events) who were followed up for 2 957 677 person-years (Table 1 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). The mean (SD) age at cohort entry was 28.3 (13.4) years for women hospitalized for bulimia and 28.3 (5.4) years for those hospitalized for pregnancy-related events. Compared with women with pregnancy-related hospitalizations, those hospitalized for bulimia had a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease (10.34 [95% CI, 7.77-13.76] vs 1.02 [95% CI, 0.99-1.06] per 1000 person-years) and deaths (3.21 [95% CI, 1.97-5.25] vs 0.10 [95% CI, 0.09-0.11] per 1000 person-years). The incidence of cardiovascular disease was highest among women who had 3 or more admissions for bulimia (25.13 [95% CI, 13.52-46.70] per 1000 person-years). Women with comorbidity had a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease (2.23 [95% CI, 2.00-2.49]) than that for women with no comorbidity (0.98 [95% CI, 0.94-1.01]).

Table 1. Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease and Death According to Characteristics of Women.

| Characteristic | No. of Women | Cardiovascular Disease | Death | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Events | Incidence per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | No. of Events | Incidence per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | ||

| Bulimia nervosa | |||||

| Yes | 818 | 47 | 10.34 (7.77-13.76) | 16 | 3.21 (1.97-5.25) |

| No | 415 891 | 2967 | 1.02 (0.99-1.06) | 299 | 0.10 (0.09-0.11) |

| No. of admissions for bulimia nervosa | |||||

| 0 | 415 891 | 2967 | 1.02 (0.99-1.06) | 299 | 0.10 (0.09-0.11) |

| 1 | 617 | 32 | 9.17 (6.48-12.97) | 12 | 3.18 (1.81-5.60) |

| 2 | 118 | 5 | 7.60 (3.16-18.26) | <5a | 3.31 (1.24-8.83)b |

| ≥3 | 83 | 10 | 25.13 (13.52-46.70) | NC | NC |

| Age at first admission, y | |||||

| <20 | 21 821 | 193 | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | 22 | 0.13 (0.09-0.20) |

| 20-24 | 80 006 | 613 | 1.07 (0.99-1.16) | 44 | 0.08 (0.06-0.10) |

| 25-29 | 149 719 | 1043 | 0.98 (0.93-1.04) | 87 | 0.08 (0.07-0.10) |

| 30-34 | 111 495 | 696 | 0.92 (0.86-0.99) | 67 | 0.09 (0.07-0.11) |

| 35-39 | 43 771 | 347 | 1.21 (1.09-1.35) | 60 | 0.20 (0.16-0.26) |

| ≥40 | 9897 | 122 | 1.92 (1.61-2.30) | 35 | 0.53 (0.38-0.74) |

| Comorbidityc | |||||

| Yes | 23 911 | 326 | 2.23 (2.00-2.49) | 58 | 0.38 (0.29-0.49) |

| No | 392 798 | 2688 | 0.98 (0.94-1.01) | 257 | 0.09 (0.08-0.10) |

| Socioeconomic deprivation | |||||

| Yes | 82 101 | 681 | 1.19 (1.10-1.28) | 79 | 0.14 (0.11-0.17) |

| No | 315 431 | 2218 | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 223 | 0.10 (0.09-0.11) |

| Rurality | |||||

| Yes | 64 846 | 585 | 1.29 (1.19-1.40) | 55 | 0.12 (0.09-0.16) |

| No | 343 439 | 2386 | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 257 | 0.11 (0.09-0.12) |

| Period | |||||

| 2006-2008 | 120 630 | 1317 | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) | 151 | 0.12 (0.10-0.14) |

| 2009-2012 | 163 754 | 1201 | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) | 129 | 0.11 (0.09-0.13) |

| 2013-2016 | 132 325 | 496 | 1.06 (0.97-1.15) | 35 | 0.07 (0.05-0.10) |

| Total | 416 709 | 3014 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 316 | 0.11 (0.10-0.12) |

Abbreviation: NC, not calculated.

The exact number of events is specified only for 5 or more events to avoid patient identification.

Results were calculated only for deaths among women with 2 or more bulimia-related admissions owing to a limited number of events.

Includes depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcohol, tobacco, or substance use.

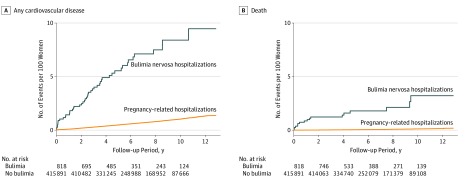

The cumulative incidence of both cardiovascular disease and death diverged between women with and without bulimia hospitalizations from the start of the study (Figure 1). Cumulative incidence rates of cardiovascular disease increased during the first 9 years of follow-up before plateauing between 9 and 12 years. The increase in cumulative death rates was slower in women hospitalized for bulimia nervosa but nonetheless pointed to a 2.5% higher difference at 12 years of follow-up compared with that in women hospitalized for pregnancy-related events.

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Any Cardiovascular Disease and Death Among Women With and Without Bulimia Nervosa.

Women diagnosed with bulimia had a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and in-hospital mortality in adjusted regression models (Table 2). Hospitalization for bulimia nervosa was associated with 4.25 (95% CI, 2.98-6.07) times the risk of any cardiovascular disease and 4.72 (95% CI, 2.05-10.84) times the risk of death during follow-up compared with those for pregnancy-related events. The HRs increased progressively with a greater number of admissions for bulimia (for ≥3 admissions, HR, 7.39 [95% CI, 3.42-15.97]). The association of bulimia with cardiovascular disease and death was significant even with adjustment for covariates.

Table 2. Association Between Bulimia Nervosa and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Death.

| Variable | HR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Disease | Death | |

| Bulimia nervosa | ||

| Yes | 4.25 (2.98-6.07) | 4.72 (2.05-10.84) |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Total admissions for bulimia nervosa | ||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 4.31 (2.92-6.35) | 3.84 (1.44-10.25) |

| 2 | 2.21 (0.61-8.04) | 7.13 (2.28-22.36)b |

| ≥3 | 7.39 (3.42-15.97) | NC |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NC, not calculated.

Adjusted for age, comorbidity (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcohol, tobacco, or substance use), socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, and period.

Results were calculated only for women with 2 or more bulimia-related admissions owing to the limited number of events.

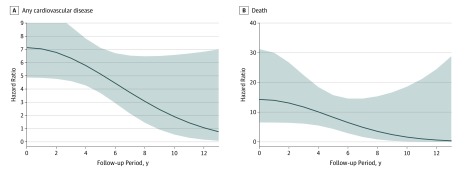

When associations were plotted over time, it was apparent that the risk of both cardiovascular disease and death decreased during the 12-year follow-up period (Figure 2). The risk of any cardiovascular disease among women hospitalized for bulimia was greatest at the start of follow-up and became similar to that for pregnancy-related hospitalizations after approximately 12 years. Bulimia was associated with 6.77 (95% CI, 4.77-9.61) times the risk of any cardiovascular disease at 2 years of follow-up compared with 5.13 (95% CI, 3.70-7.12) times the risk at 5 years (Table 3). A similar pattern of reduced risk over time was observed for death. This pattern was present regardless of the number of admissions for bulimia.

Figure 2. Association of Bulimia Nervosa With Any Cardiovascular Disease and Death Over Time.

Hazard ratio (curve) and 95% CI (shaded bands) for bulimia nervosa hospitalizations vs pregnancy-related hospitalizations adjusted for age, comorbidity (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcohol, tobacco, or substance use), socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, and period.

Table 3. Association Between Bulimia Nervosa and Specific Cardiovascular Outcomes.

| Outcome | No. of Events | HR (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulimia | No Bulimia | At 2-y Follow-up | At 5-y Follow-up | Over Entire Follow-up | |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 47 | 2967 | 6.77 (4.77-9.61) | 5.13 (3.70-7.12) | 4.25 (2.98-6.07) |

| Myocardial infarction | 9 | 144 | 21.93 (9.29-51.74) | 14.13 (6.02-33.18) | 5.48 (1.80-16.70) |

| Other ischemic heart disease | 17 | 348 | 16.92 (8.76-32.68) | 11.84 (6.52-21.53) | 6.63 (3.34-13.13) |

| Conduction disorder | 12 | 1197 | 5.32 (2.74-10.30) | 3.12 (1.51-6.44) | 2.99 (1.57-5.71) |

| Pulmonary vascular disease | 11 | 469 | 8.73 (4.42-17.24) | 4.17 (1.68-10.35) | 4.78 (2.16-10.61) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | <5 | 354 | 4.74 (1.45-15.45) | 3.85 (1.34-11.06) | 3.11 (0.75-12.97) |

| Atherosclerosis | 16 | 122 | 32.21 (14.74-70.42) | 18.26 (9.05-36.84) | 6.94 (3.08-15.66) |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 13 | 760 | 5.91 (3.03-11.51) | 5.04 (2.81-9.05) | 4.12 (2.03-8.36) |

| Coronary care unit admission | 6 | 396 | 9.27 (3.97-21.67) | 2.40 (0.63-9.16) | 5.20 (2.08-12.95) |

| Death | 16 | 299 | 13.09 (6.41-26.73) | 8.27 (4.35-15.71) | 4.72 (2.05-10.84) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Adjusted for age, comorbidity (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcohol, tobacco, or substance use), socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, and period.

Bulimia nervosa was associated with most cardiovascular diseases (Table 3). In adjusted models, women hospitalized for bulimia had 5.48 (95% CI, 1.80-16.70) times the risk of myocardial infarction, 6.63 (95% CI, 3.34-13.13) times the risk of other ischemic heart disease, 2.99 (95% CI, 1.57-5.71) times the risk of conduction disorders, and 6.94 (95% CI, 3.08-15.66) times the risk of atherosclerosis compared with women hospitalized for pregnancy-related events. Risks were elevated for all other cardiovascular outcomes. Women hospitalized for bulimia also had more than 5.20 (95% CI, 2.08-12.95) times the risk of admission to a coronary care unit. Bulimia was associated with 21.93 (95% CI, 9.29-51.74) times the risk of myocardial infarction at 2 years and 14.13 (95% CI, 6.02-33.18) times the risk at 5 years.

In sensitivity analyses, associations were observed for both gravid and nongravid women diagnosed with bulimia, and using age 10 years as the start time yielded a similar interpretation. Restricting the analysis to women whose first hospitalization occurred before 2013, when the definition of bulimia was stricter, also produced similar results.

Discussion

In this longitudinal cohort study of 416 709 women, hospitalization for bulimia nervosa was associated with a significantly elevated risk of cardiovascular disease and death during 12 years of follow-up compared with that for pregnancy-related hospitalizations. A diagnosis of bulimia nervosa increased the risk of cardiovascular disease and death more than 4-fold. Risks were greatest within 2 years of the index bulimia-related hospitalization and remained elevated until 5 years later before disappearing by around 10 years of follow-up. This pattern was observed for several cardiovascular problems, including myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, other ischemic heart disease, and conduction disorders. Although more studies are needed, the findings from the present study suggest that bulimia nervosa, especially bulimia that requires multiple hospitalizations for treatment, may be associated with a range of cardiovascular disorders. Bulimia nervosa may be an important contributor to premature cardiovascular disease in women.

Little is known about the mid- to long-term associations of bulimia nervosa with the cardiovascular system. Most of the literature focuses on acute consequences, including immediate hemodynamic changes and electrical conduction defects due to excessive purging and fluid loss.19,20,21 Bulimia is associated with reduced blood pressure, pulse rate, and oxygen saturation during active disease.1 Electrical conduction defects in bulimia coincide with electrolyte imbalance and hypokalemia.19,20,21 In women diagnosed with severe bulimia and hypokalemia, QT interval prolongation and repolarization abnormalities may lead to sudden acute ventricular arrhythmias and death.21 A study of 52 women diagnosed with bulimia in the United States who binged and purged found a lower R-wave amplitude on the electrocardiogram, indicating reduced cardiac contractile force and signaling.19 Women with an altered R-wave amplitude in the study were more likely to have sudden ventricular arrhythmias.19 However, not all studies support an acute association of bulimia with changes in the myocardium. A recent study in Denmark of 531 women with bulimia and 125 women without found no evidence of an association of bulimia with QT prolongation or with immediate cardiac events and all-cause mortality.20 Regardless of the short-term association between bulimia and cardiac events, it is likely that conduction defects due to electrolyte imbalance are reversible.21

Bulimia nervosa is associated with metabolic changes that have the potential to affect the risk of chronic nonreversible cardiovascular disease.22,23 Bulimia can alter lipid profiles when women are at an early reproductive age.22,23 The proportion of women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa who have hypercholesterolemia ranges from 19% to 48%.23 Cyclical patterns of binging followed by restrictive eating or purging is thought to be responsible for these metabolic alterations.19,23 Average binge episodes can be excessive and include processed foods with caloric intakes of 2415 kcal on average, although intakes of 4000 kcal per binge are also possible.24 Excess consumption of fat and carbohydrates can influence lipoprotein metabolism and have atherogenic effects that are associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease.25

In addition, bulimia nervosa may cause endocrine abnormalities that further alter metabolic profiles.26 Women diagnosed with bulimia commonly have low estrogen levels,26 which may be negatively associated with cardiovascular health in the long term. Women with a history of bulimia also tend to have adverse lifestyles, including tobacco, drug, and alcohol use, which contribute to cardiovascular disease.27

An increasing number of studies indicate that bulimia nervosa has a genetic component.1,28 Family and twin studies show that bulimia is heritable in 50% to 83% of cases.1 Genetic factors that predispose women to eating disorders are also linked with depression29 and anxiety,7 which are mental disorders associated with the risk of both cardiac events and death.2 Although the possibility that genetic factors explain the association of eating disorders with cardiovascular morbidity has yet to be studied, genetics is widely accepted to be an important contributor to cardiovascular disease in general.2 The associations between bulimia and ischemic cardiac events, cerebrovascular disorders, and other cardiovascular disease in our data raise the possibility of a genetic connection between both disorders.

In the present study, the association between bulimia and cardiovascular disease decreased over time. The risk was greatest in the first few years after the initial (index) bulimia hospitalization. The trajectory of bulimia is poorly understood, but some data suggest that approximately half of the women diagnosed recover within 5 to 10 years,27 which roughly aligns with the time when risk began to diminish in our results. Thus, the decreasing risk over time may reflect women who successfully recovered from bulimia. In such women, the critical period for cardiovascular disease may be within 5 to 10 years of the index bulimia admission.

Nonetheless, bulimia can be chronic in a considerable proportion of women.1 In our population, chronic severe bulimia is more likely because we identified hospitalized cases, which may be more resistant to treatment. Admission for bulimia may imply greater disease severity or comorbidity that may be associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease. These women may develop cardiovascular outcomes more rapidly, leaving fewer women available to acquire cardiovascular disease over time. If bulimia is a strong risk factor for cardiovascular disease, the association will be greatest early in the study and will gradually decrease over time with the reduction in the number of susceptible women at risk.30 The tendency for HRs to decrease over time may therefore reflect the importance of bulimia as a risk factor for premature cardiovascular disease. Hazard ratios can capture changes in the magnitude of associations over time, including associations of strong risk factors that quickly cause the outcome.30

Limitations

This study has several limitations. We relied on hospitalization data and could not identify women diagnosed with mild bulimia who never required hospital treatment. Misclassification may be present. We did not have information on the duration of bulimia, including remissions or relapses, which may further be associated with cardiovascular disease. We could not analyze binge-eating disorder, which shares features of bulimia but without purging or other compensatory behavior. We did not have laboratory measures of electrolytes, serum cholesterol, or triglycerides.23 Information such as quality of diet and physical activity was not available, but these may contribute to cardiovascular disease.25 Smoking status may be underestimated. It is possible that the women in our cohort did not age enough to develop some of the longer-term cardiovascular complications that typically occur after menopause. A longer follow-up period could potentially reveal a more distal association with cardiovascular disease, which is an important topic for future research. We analyzed in-hospital mortality and could not identify women who died outside hospitals, although in Quebec most deaths occur in hospitals. We could not perform a detailed analysis of cause of death owing to low numbers of events and cannot confirm that the deaths were related to cardiovascular disease. We compared women diagnosed with bulimia with women without bulimia who had a history of pregnancy, a group representative of gravid women. However, we could not include women who were never pregnant in the comparison group. Menstrual irregularities and chronic disease are more common in nonpregnant women, which may mask associations. Although sensitivity analyses suggested that our results were robust to different assumptions, future research should explore alternative designs. The results of this study can be generalized to a large Canadian and culturally diverse province, but findings may differ in other study settings.

Conclusions

In this longitudinal cohort study with 12 years of follow-up, the results suggest that bulimia nervosa may be significantly associated with the risk of several adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, other ischemic heart disease, atherosclerosis, and conduction disorders. The risks for adverse outcomes were most increased in the first 5 years after the index bulimia-related hospitalization and decreased thereafter. Our findings suggest that women with a history of bulimia nervosa should be informed of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and death in the first decade after the index admission for bulimia. These women may benefit from screening for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors.

eTable 1. Diagnostic and Procedure Codes for Cardiovascular Disease

eTable 2. Diagnostic and Procedure Codes for Preexisting Comorbidity

eTable 3. Characteristics of Women With and Without Bulimia Nervosa

References

- 1.Treasure J, Claudino AM, Zucker N. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):583-593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61748-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Hert M, Detraux J, Vancampfort D. The intriguing relationship between coronary heart disease and mental disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):31-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Swanson SA, et al. . Increased mortality in bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1342-1346. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucholz EM, Butala NM, Rathore SS, Dreyer RP, Lansky AJ, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Circulation. 2014;130(9):757-767. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehler PS, Rylander M. Bulimia nervosa—medical complications. J Eat Disord. 2015;3(12). doi: 10.1186/s40337-015-0044-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM. State of the art review: depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(11):1295-1302. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keel PK, Klump KL, Miller KB, McGue M, Iacono WG. Shared transmission of eating disorders and anxiety disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(2):99-105. doi: 10.1002/eat.20168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health and Social Services Med-Echo System Normative Framework—Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele. Ville de Quebec, Quebec: Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux; 2018. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2000/00-601.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert L, Blais C, Hamel D, et al. . Evaluation of care and surveillance of cardiovascular disease: can we trust medico-administrative hospital data? Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(2):162-168. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ, Klungsøyr K, et al. . Cardiovascular mortality after pre-eclampsia in one child mothers: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e7677. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz AM, Gonçalves-Pinho M, Santos JV, Coutinho F, Brandão I, Freitas A. Eating disorders-related hospitalizations in Portugal: a nationwide study from 2000 to 2014. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(10):1201-1206. doi: 10.1002/eat.22955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Institute for Health Information Canadian Classification of Health Interventions: volume four—alphabetical index. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/cci_volume_four_2015_en_0.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 13.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Westreich DJ, Greenland S, Napravnik S, Eron JJ Jr. Splines for trend analysis and continuous confounder control. Epidemiology. 2011;22(6):874-875. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823029dd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien KM, Whelan DR, Sandler DP, Hall JE, Weinberg CR. Predictors and long-term health outcomes of eating disorders. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pampalon R, Raymond G. A deprivation index for health and welfare planning in Quebec. Chronic Dis Can. 2000;21(3):104-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin G, So Y, Johnston G Analyzing survival data with competing risks using SAS software. SAS Global Forum website. http://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings12/344-2012.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed September 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fine J, Gray R. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald DE, McFarlane TL, Olmsted MP. “Diagnostic shift” from eating disorder not otherwise specified to bulimia nervosa using DSM-5 criteria: a clinical comparison with DSM-IV bulimia. Eat Behav. 2014;15(1):60-62. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green M, Rogers J, Nguyen C, et al. . Cardiac risk and disordered eating: decreased R wave amplitude in women with bulimia nervosa and women with subclinical binge/purge symptoms. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2016;24(6):455-459. doi: 10.1002/erv.2463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frederiksen TC, Christiansen MK, Østergaard PC, et al. . The QTc interval and risk of cardiac events in bulimia nervosa: a long-term follow-up study. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(12):1331-1338. doi: 10.1002/eat.22984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jáuregui-Garrido B, Jáuregui-Lobera I. Sudden death in eating disorders. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;8(8):91-98. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S28652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan PF, Gendall KA, Bulik CM, Carter FA, Joyce PR. Elevated total cholesterol in bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(4):425-432. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteleone P, Santonastaso P, Pannuto M, et al. . Enhanced serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels in bulimia nervosa: relationships to psychiatric comorbidity, psychopathology and hormonal variables. Psychiatry Res. 2005;134(3):267-273. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpers GW, Tuschen-Caffier B. Energy and macronutrient intake in bulimia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2004;5(3):241-249. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siri-Tarino PW, Chiu S, Bergeron N, Krauss RM. Saturated fats versus polyunsaturated fats versus carbohydrates for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment. Annu Rev Nutr. 2015;35(1):517-543. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071714-034449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren MP. Endocrine manifestations of eating disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):333-343. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krug I, Treasure J, Anderluh M, et al. . Present and lifetime comorbidity of tobacco, alcohol and drug use in eating disorders: a European multicenter study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97(1-2):169-179. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzeo SE, Mitchell KS, Bulik CM, Aggen SH, Kendler KS, Neale MC. A twin study of specific bulimia nervosa symptoms. Psychol Med. 2010;40(7):1203-1213. doi: 10.1017/S003329170999122X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slane JD, Burt SA, Klump KL. Genetic and environmental influences on disordered eating and depressive symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(7):605-611. doi: 10.1002/eat.20867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernán MA. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):13-15. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Diagnostic and Procedure Codes for Cardiovascular Disease

eTable 2. Diagnostic and Procedure Codes for Preexisting Comorbidity

eTable 3. Characteristics of Women With and Without Bulimia Nervosa