Key Points

Question

Is there a greater risk of developing Parkinson disease (PD) in people with bipolar disorder (BD)?

Findings

In this meta-analysis and systematic review including 7 studies and more than 4 million participants, a previous diagnosis of BD increased the likelihood of a subsequent diagnosis of idiopathic PD.

Meaning

If patients with BD present parkinsonism features, a diagnosis of PD should be considered, independently of concomitant medication.

This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses the association of bipolar disorder with a later diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson disease.

Abstract

Importance

Parkinson disease (PD) manifests by motor and nonmotor symptoms, which may be preceded by mood disorders by more than a decade. Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by cyclic episodes of depression and mania. It is also suggested that dopamine might be relevant in the pathophysiology of BD.

Objective

To assess the association of BD with a later diagnosis of idiopathic PD.

Data Sources

An electronic literature search was performed of Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO from database inception to May 2019 using the terms Parkinson disease, bipolar disorder, and mania, with no constraints applied.

Study Selection

Studies that reported data on the likelihood of developing PD in BD vs non-BD populations were included. Two review authors independently conducted the study selection.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two review authors independently extracted study data. Data were pooled using a random-effects model, results were abstracted as odds ratios and 95% CIs, and heterogeneity was reported as I2.

Main Outcome and Measures

Odds ratios of PD.

Results

Seven studies were eligible for inclusion and included 4 374 211 participants overall. A previous diagnosis of BD increased the likelihood of a subsequent diagnosis of idiopathic PD (odds ratio, 3.35; 95% CI, 2.00-5.60; I2 = 92%). A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing the studies that had a high risk of bias and also showed an increased risk of PD in people with BD (odds ratio, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.89-5.45; I2 = 94%). Preplanned subgroup analyses according to study design and diagnostic certainty failed to show a significant effect.

Conclusions and Relevance

This review suggests that patients with BD have a significantly increased risk of developing PD compared with the general population. Subgroup analyses suggested a possible overestimation in the magnitude of the associations. These findings highlight the probability that BD may be associated with a later development of PD and the importance of the differential diagnosis of parkinsonism features in people with BD.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a mood disorder that has an early onset at a median age of 20 years. It is a long-term and recurrent disorder characterized by cyclic episodes of depression and either mania (BD type 1) or hypomania (BD type 2). Although the etiology of BD has not been established, it is a multifactorial disorder with genetic and environmental factors playing an important role.1 Despite the pathophysiology of BD being uncertain, there is a putative role of the dopaminergic system, as levodopa has been shown to induce hypomania or mania in patients with BD,2 and antipsychotic medications that block dopamine receptors can improve manic symptoms.3 There is also evidence that the switch from a depressive to a manic state occurs concurrently with an upregulation of dopamine receptors.4

The standard treatment for BD that includes lithium, antipsychotic medications, and antiepileptic medications may be associated with drug-induced parkinsonism, which is not clinically distinguishable from Parkinson disease (PD), both being characterized by bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, and postural instability.5,6,7 Since drug-induced parkinsonism is more common among patients with BD, physicians may be more inclined to misdiagnose PD as drug-induced parkinsonism. On the other hand, PD is typically seen in older patients. Small studies have previously shown that BD may be more common in patients with PD compared with the general population.6 Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to assess the possible association of BD with a later diagnosis of idiopathic PD.

Methods

This study was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018090100). This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline. We searched Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO from database inception to May 2019 for observational studies of any design, namely cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies, that reported data on the association of idiopathic PD in BD vs non-BD populations (eMethods in the Supplement). Two review authors (P.R.F. and G.S.D.) independently screened all titles and abstracts identified from the search. We retrieved any articles identified as potentially relevant by at least 1 review author. Two review authors (P.R.F. and G.S.D.) independently screened full-text articles, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. The references of relevant studies were cross-checked for additional studies not identified by the electronic search.

Two review authors (P.R.F. and G.S.D.) independently extracted data from the included studies using a piloted data extraction form, resolving any discrepancies through discussion. The information extracted included the study characteristics (publication year, country of origin, study period, study design, and length of follow-up), participant characteristics (number, age, and sex), selection of cases and controls in case-control studies, assessment of BD diagnosis and outcome, adjustment for potential confounders, and estimates of the association of BD with PD.

We assessed the risk of bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale8 and arbitrarily judged studies with scores greater than 6 as having a low overall risk of bias. We conducted data analyses using Review Manager version 5.3 (Cochrane). We pooled data, where adequate, using a random-effects model and reported results using odds ratio (OR) estimates with corresponding 95% CIs. We quantified heterogeneity using I2. We further explored our results using preplanned subgroup analyses according to study design, duration of follow-up, and if the BD diagnosis was clearly established before PD diagnosis, with an arbitrary cutoff of 9 years. We also conducted a preplanned sensitivity analysis by pooling only studies at a low overall risk of bias. We intended to assess the possibility of publication bias,9 although we were unable to do so owing to an insufficient number of included trials. Variables were compared using χ2 tests. All tests were 2-tailed, and we considered a P value less than .05 to be statistically significant.

Results

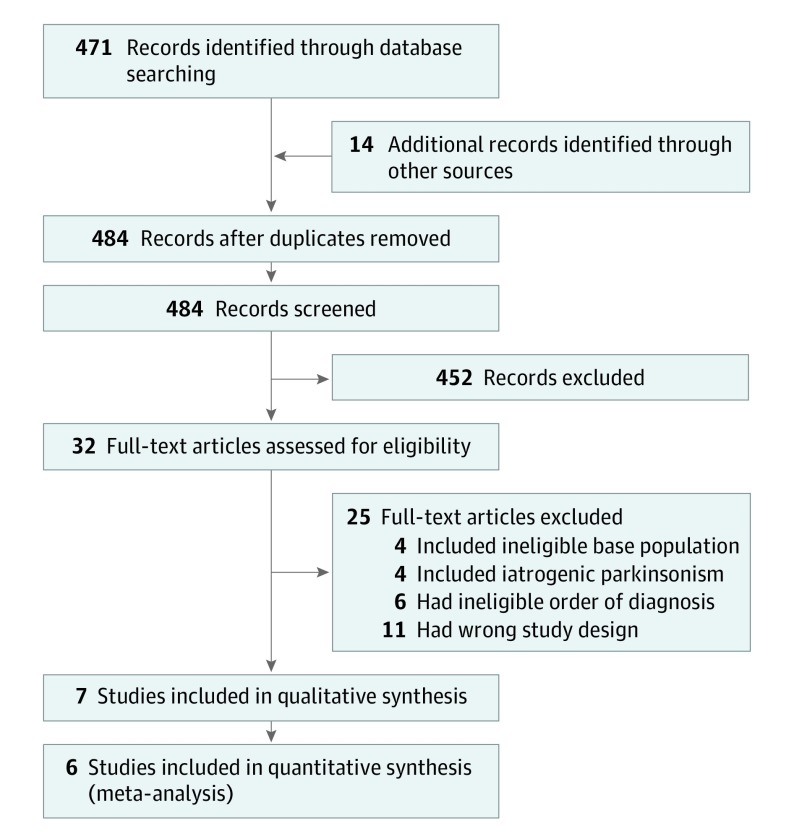

The electronic database search identified 471 articles. After title and abstract screening, 32 articles were retained for full-text assessment, with 7 fulfilling our review criteria, including 4 cohort studies10,11,12,13 and 3 cross-sectional studies14,15,16 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Most of the included studies did not state the criteria used to establish the diagnosis of PD, as these were generally based on data from registers and medical records, and one study used a self-report questionnaire.14 Another study mentioned using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging to exclude other neurological diseases.10 However, none used specific imaging methods for the differential diagnosis of PD and parkinsonism. Only 1 of the included trials reported the average age at onset of PD.13 The population characteristics and outcomes of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Source | Study Design | Location | Population; Age | Control Population | Method of Diagnosis; Age at Onset | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD | PD | ||||||

| Forty et al,14 2014 | Cross-sectional | United Kingdom | 1720 Patients with BD and 1340 controls (70% female); median age in BD group, 47 y | General population | Medical records using DSM-IV and ICD-10; median (IQR) age, 20 (7-55) y | Self-reported diagnosis of PD; NR | Lifetime rate of self-reported PD, 0.6% in BD group vs 0.1% in control group |

| Huang et al,13 2019 | Prospective cohort (2001-2011) | Taiwan | 56 340 Patients with BD and 225 360 age-and sex-matched controls; NR | General population | Medical records using ICD-9; median (SD) age, 39.98 (13.63) y | Medical records using ICD-9; median (SD) age, 64.25 (11.63) y | Adjusted HR, 5.82; 95% CI, 4.89-6.93 |

| Kilbourne et al,15 2004 | Cross-sectional | United States | 4310 Patients with BD and 3 408 760 controls (10% female); median age in BD group, 53 y | US army veterans | Medical records using ICD-9; NR | Record linkage diagnosis; NR | Lifetime rate of self-reported PD, 0.1% in BD group vs 0.9% in control group |

| Lin et al,10 2014 | Retrospective cohort (2001-2009) | Taiwan | 1203 Hospitalized patients with BD and 220 971 controls (38% female); NR | General population | Record linkage diagnosis using ICD-9; NR | Record linkage diagnosis; NR | Adjusted OR, 5.02; 95% CI, 3.85-6.55 |

| Marras et al,11 2016 | Retrospective cohort (2002-2013) | Ontario, Canada | 1749 Patients medicated with lithium, 285 154 patients medicated with antidepressants (54% to 58% female); NR | General population | Medical records via lithium medication; NR | Record linkage diagnosis via antiparkinsonian medication; NR | Adjusted HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.13-2.48 |

| Nilsson et al,12 2001 | Prospective cohort (1977-1993) | Denmark | 2007 Patients with mania and 162 715 healthy controls (53% female); median age in mania group, 50.6 y | Hospital setting | Medical records; NR | Record linkage diagnosis; NR | 7 of 2007 Patients with mania (0.4%) developed PD |

| Smith et al,16 2013 | Cross-sectional | Scotland | 2582 Patients with BD (61% female); median age, 54.5 y | General population | Medical records using Read Codes; NR | Record linkage diagnosis; NR | OR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.83-5.09 |

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; IQR, interquartile range; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; PD, Parkinson disease.

Systematic Review

The cohort study by Lin et al10 included 73 597 patients with an established psychiatric disorder who were recruited between 2001 and 2003, among whom 1203 had BD, and these individuals were matched with 220 971 controls. The selection was made using medical records of hospitalizations and ambulatory care. Patients were observed for 6 years to identify PD. In this 6-year follow-up, patients with BD were at an increased risk of developing PD compared with the control group (adjusted hazard ratio, 5.02; 95% CI, 3.85-6.55). This result was adjusted for age and sex.

The use of lithium and PD diagnosis was assessed in a study by Marras et al11 that used data from the Ontario administrative health care database between 2002 and 2011. The results showed that compared with antidepressant therapy (285 154 patients), lithium monotherapy (1749 patients) was associated with an increased risk of antiparkinsonian drug use or PD diagnosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.13-2.48). This result was adjusted for age, long-term care residence, dementia, Charlson Commodity Index score, and antipsychotic use after the index date. However, the diagnostic code may not differentiate PD from other causes of parkinsonism, and cases of atypical parkinsonism may have been included. Nevertheless, patients using an antiparkinsonian medication who had a history of PD or parkinsonism in the previous 5 years were excluded. The control group in this study consisted of patients with unipolar depression, which also increases the risk of developing PD over time.

Nilsson et al12 assessed psychiatric admissions between 1977 and 1993 among 164 722 patients with multiple psychiatric and nonpsychiatric disorders. Patients with the diagnosis of mania at discharge were compared with a control group who had osteoarthritis or diabetes. The difference in the risk of PD diagnosis in the mania vs control groups was not statistically significant, but among 2007 patients with mania, 7 patients (0.3%) developed PD. It is important to consider that parkinsonism was not excluded in this study, implying that incorrect diagnoses may have occurred.

A cohort study by Huang et al,13 conducted with data from 2001 to 2009 and with follow-up until 2011, was designed to assess the risk of developing PD among people with BD. A total of 56 340 patients with BD and 225 360 healthy controls were included. Excluding the diagnosis of PD within the first year of the observation period, the study found an increased risk of PD among patients with BD during the follow-up period (hazard ratio, 5.82; 95% CI, 4.89-6.93).

Forty et al14 conducted a cross-sectional study that enrolled 1720 patients with BD who were interviewed regarding their history of multiple medical conditions, among which PD was included. The data were compared with data from a similar population who had unipolar mood disorders (1737 patients) and a control group (1340 patients). In the BD group, a 0.6% lifetime rate of self-reported PD was found, while in both the unipolar mood disorder and control groups, the rate of self-reported PD was 0.1%. This study also found a significant difference between BD types 1 and 2, with those with BD type 2 having a greater self-reported proportion of PD. This study has the notable issue of being based on self-reported diagnoses, an unreliable data collection method. Additionally, the control group was selected from a different source than patients with BD and unipolar depression.

An additional cross-sectional study by Kilborune et al15 enrolled 4310 patients with BD receiving care in veteran centers and retrospectively analyzed these patients for PD. This study found a significantly lower number of patients with PD in the BD group compared with controls. However, this study was conducted using a specific subgroup of veterans, and the data present challenges regarding both their internal and external validity.

Another cross-sectional study by Smith et al,16 with patients from primary care practices in Scotland, identified 2582 patients with BD and 1 421 796 patients without PD. The prevalence of PD or parkinsonism was higher for patients with BD compared with the control group (OR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.83-5.09). In this cross-sectional study, it is not clear which diagnosis came first, BD or PD, and the possibility of drug-induced parkinsonism is not excluded, which may lead to an overestimation of the risk of PD in the BD cohort.

The risk of bias of the included studies was moderate overall. A total of 5 studies were considered to have a low overall risk of bias (Table 2).

Table 2. Study Assessment According to Newcastle-Ottawa Rating Scalea.

| Source | Study Design | Selection | Comparability | Exposure/Outcome | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forty et al,14 2014 | Cross-sectional | NA | NA | ★★ | 2 |

| Huang et al,13 2019 | Prospective cohort | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | 8 |

| Kilbourne et al,15 2004 | Cross-sectional | ★★ | ★ | ★★★ | 6 |

| Lin et al,10 2014 | Retrospective cohort | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 8 |

| Marras et al,11 2016 | Retrospective cohort | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | 8 |

| Nilsson et al,12 2001 | Prospective cohort | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9 |

| Smith et al,16 2013 | Cross-sectional | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Rated on a scale of 1 star to 9 stars.

Meta-analysis

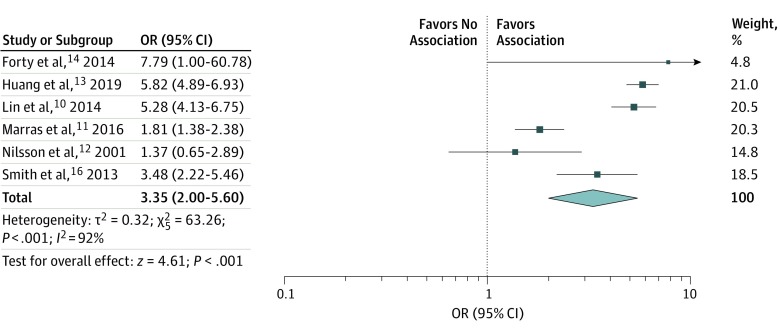

We decided to exclude the results from the cross-sectional study that enrolled a population of veterans15 because of doubts over internal and external validity. We pooled data reporting the risk of PD in BD vs non-BD populations, as defined in the studies, and found that a previous diagnosis of BD significantly increased the risk of subsequent PD diagnosis (OR, 3.35; 95% CI, 2.00-5.60; I2 = 92%) (Figure 2). We conducted a sensitivity analysis by removing the studies that had a high risk of bias, which also showed an increased risk of PD in people with BD (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.89-5.45; I2 = 94%) (eTable in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Odds Ratios (ORs) for Association of Bipolar Disorder With Parkinson Disease.

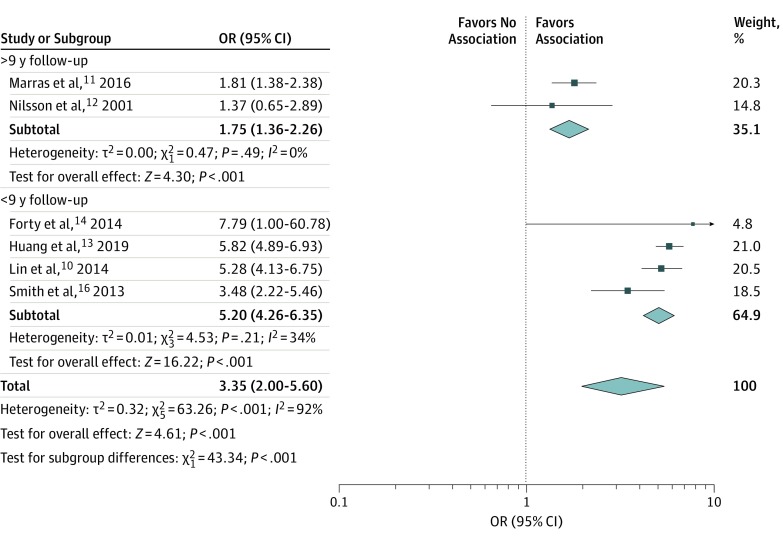

In the subgroup analysis based on the duration of follow-up (Figure 3), we found that both subgroups, ie, those with more and less than 9 years of follow-up, reported an increased risk of PD (more than 9 years: OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.36-2.26; I2 = 0%; less than 9 years: OR, 5.20; 95% CI, 4.26-6.35; I2 = 34%). However, we found a statistically significant difference between the subgroups, indicating that the subgroup with the shorter follow-up was associated with a greater increase in the risk of PD diagnosis. In the subgroup analysis based on study design and diagnosis certainty, we found both subgroups reported an increased risk of PD, although subgroup analyses did not show a statistically significant difference between the subgroups.

Figure 3. Odds Ratios (ORs) for Association of Bipolar Disorder With Parkinson Disease by Duration of Follow-up.

Given a possible overlap between the participants in 2 of the included studies,10,13 we conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis by removing the study by Lin et al.10 The results were consistent with the overall results, and there was still a significant association of BD with subsequent PD diagnosis (OR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.50-5.98; I2 = 93%).

A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted to include the single study with a negative association between BD and PD.15 The results were consistent with the overall results, there still being an association of BD with subsequent PD diagnosis (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.35-4.33; I2 = 93%).

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that people with BD have a significantly increased likelihood of later developing PD. When placed in the context of other systematic reviews looking at risk factors for PD, our statistical evidence is highly suggestive. Only 7 of 38 reviews included in an overview of systematic reviews presented results at least as robust as the evidence we present.17 This is a result of the large number of events in our review, the very small P values for the association, and the fact that the 95% CIs of the largest study does not cross the null value.

The pathophysiological rationale between BD and PD might be explained by the dopamine dysregulation hypothesis,4 which states that the cyclical process of BD in manic states leads to a downregulation of dopamine receptor sensitivity (depression phase), which is later compensated by upregulation (manic state). Over time, this phenomenon may lead to an overall reduction of dopaminergic activity, the prototypical PD state. This hypothesis justifies the highly suggestive association we found of BD with PD. Reinforcing the link between BD and PD is the well-known fact that mood changes are related to the on-time/off-time phenomena in PD. In the on-time phase, mania-like symptoms are more common, unlike the off-time phase, which is more commonly associated with depressive symptoms.18 However, it should be mentioned that BD is not associated with overt evidence of neurodegeneration, and while mood phenomena fluctuations may be similar, the processes underlying the on-time/off-time mood states in PD are distinct from sustained abnormal mood fluctuations in BD, including involvement of other neurochemical systems besides dopamine.

It would be of interest to establish the causal relationship of this association, although this remains elusive. The pathophysiological rationale would seem to corroborate our findings as well as the reported improvement of motor symptoms seen with the manic episodes and the worsening of mania with the dopaminergic medication reported in some studies. There is also a possibility that the increased risk of PD in patients with BD derives from long-term lithium use, since most patients with BD are prescribed the drug for long-term use and, along with other drugs used in the management of BD, such as antipsychotics, may lead to parkinsonism. However, treatment with lithium is foundational in BD, and so to separate the causal effect from a potential confounder would be particularly difficult. Beyond this, it may be a purely academic effort, as the very fact that this association is present would already be of clinical value for patients with BD.

The evidence from subgroup analysis suggests that these are not spurious findings based on data dredging of health care databases. The door is open for future research to investigate the reasons for the association. Is there overlap in genetic risk factors for BD or PD? Is the risk of developing PD greater in patients with BD with PD genetic factors, head trauma, other evidence of synucleinopathies, or other environmental exposures? Is BD just one more example of a brain disorder that is evident earlier in life that confers a risk for a later neurodegenerative disorder? The study of those with BD as a high-risk population for developing PD may further be explored as a form of enrichment for PD populations. Future studies should be designed to provide a more definitive answer regarding this association. Ideally, the criteria used for both the diagnosis of BD and PD should be clearly stated, as should the age of diagnosis for each disorder. Bearing in mind the difference in the expected age at onset, the follow-up period ought to be longer. Also, when necessary, specific imaging methods should be used to differentiate PD from drug-induced parkinsonism so there is lower uncertainty regarding PD diagnosis.

Limitations

The main limitation comes from a subgroup analysis showing a greater likelihood of PD diagnosis in shorter studies, leading to concern over the misdiagnosis of parkinsonism (probably drug-induced in origin) as PD and residual confounding. In fact, one study explicitly did not differentiate between the 2 conditions.16 As the subgroup analysis based on follow-up time suggests, this contamination may overestimate the association. However, in the subgroup with longer follow-up, where the likelihood of misclassification is expected to be lower, the association was strong and without statistical heterogeneity. As our results were overwhelmingly based on real-world medical records, this estimate may be considered generalizable to the general population. This should reinforce the importance of the differential diagnosis between parkinsonism and PD in the BD population.

It is relevant to explore the statistical heterogeneity in the included studies. Since the association between these 2 conditions is not commonly looked for, most of the data came from studies where this was not the primary objective. This may partially account for the high degree of statistical heterogeneity found on meta-analysis. It is nonetheless relevant that the overall tendency of the results, as seen on visual inspection of the forest plot, is apparently homogeneous, with all but 2 studies suggesting the association. Additionally, statistical heterogeneity decreased in the subgroup analysis, suggesting that the overall heterogeneity is also partially due to the difference between shorter-term and longer-term studies. As the results of the included studies are based on large databases with few PD-specific reported characteristics, we were unable to assess other factors that may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

Conclusions

The main clinical implication of this review should be to underline that if patients with BD present with parkinsonism features, this may not be drug induced and may recommend the investigation of PD. To clinically distinguish parkinsonism from PD in clinical practice, the use of functional neuroimaging methods may be of particular interest, as PD classically presents with nigrostriatal degeneration while drug-induced parkinsonism does not. Additionally, there are implications for the care of patients with BD, namely with longitudinal motor assessments, monitoring for prodromal motor or nonmotor signs of PD, and eventually by parkinsonism risk mitigation via medication selections and nonpharmacological treatments.

These results may invite many questions from people with BD and their physicians. Are all subtypes of BD at an equal risk? Is the risk present even when the diagnosis is made at a young age? What are the roles of lithium and antipsychotics? We would be interested in seeing these questions examined in large prospective cohorts of patients with BD, including detailed movement disorder evaluations and dopamine transporter imaging outcomes.

eMethods. Search strategies.

eTable. 95% CIs of I2 estimates.

References

- 1.Vieta E, Berk M, Schulze TG, et al. Bipolar disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:192. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy DL, Brodie HK, Goodwin FK, Bunney WE Jr. Regular induction of hypomania by L-dopa in “bipolar” manic-depressive patients. Nature. 1971;229(5280):135-198. doi: 10.1038/229135a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilty DM, Brady KT, Hales RE. A review of bipolar disorder among adults. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(2):201-213. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.2.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berk M, Dodd S, Kauer-Sant’anna M, et al. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: implications for a dopamine hypothesis of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2007;116(434):41-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin HW, Chung SJ. Drug-induced parkinsonism. J Clin Neurol. 2012;8(1):15-21. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2012.8.1.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis AW, Thibault DP, Schmidt PN, Dorsey ER, Weintraub D. Hospital care for mental health and substance abuse conditions in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(12):1810-1819. doi: 10.1002/mds.26832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noyce AJ, Bestwick JP, Silveira-Moriyama L, et al. Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(6):893-901. doi: 10.1002/ana.23687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 9.Sterne J, Egger M, Moher D, Boutron I. Addressing reporting biases In: Higgins J, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston M, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.2.0. London, United Kingdom: Cochrane; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin HL, Lin HC, Chen YH. Psychiatric diseases predated the occurrence of Parkinson disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(3):206-213. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marras C, Herrmann N, Fischer HD, et al. Lithium use in older adults is associated with increased prescribing of Parkinson medications. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(4):301-309. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson FM, Kessing LV, Bolwig TG. Increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease for patients with major affective disorder: a register study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(5):380-386. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2001.00372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang M-H, Cheng C-M, Huang K-L, et al. Bipolar disorder and risk of Parkinson disease: a nationwide longitudinal study. Neurology. 2019;92(24):e2735-e2742. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forty L, Ulanova A, Jones L, et al. Comorbid medical illness in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):465-472. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al. Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):368-373. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith DJ, Martin D, McLean G, Langan J, Guthrie B, Mercer SW. Multimorbidity in bipolar disorder and undertreatment of cardiovascular disease: a cross sectional study. BMC Med. 2013;11:263. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nissenbaum H, Quinn NP, Brown RG, Toone B, Gotham AM, Marsden CD. Mood swings associated with the ‘on-off’ phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease. Psychol Med. 1987;17(4):899-904. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700000702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Search strategies.

eTable. 95% CIs of I2 estimates.