Abstract

Associations between stressful life events (SLEs) and internalizing psychopathology are complex and bidirectional, involving interactions among stressors across development to predict psychopathology (i.e., stress sensitization) and psychopathology predicting greater exposure to SLEs (i.e., stress generation). Although stress sensitization and generation theoretical models inherently focus on within-person effects, most previous research has compared average levels of stress and psychopathology across individuals in a sample (i.e., between-person effects). The present study addressed this gap by investigating stress sensitization and stress generation effects in a multi-wave, prospective study of SLEs and adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms. Depression, anxiety, and SLE exposure were assessed every 3-months for 2-years (8 waves of data) in a sample of adolescents (n=382, aged 11 to 15 at baseline). Multi-level modeling revealed within-person stress sensitization effects such that the association between within-person increases in SLEs and depression, but not anxiety, symptoms was stronger among adolescents who experienced higher average levels of SLEs across 2-years. We also observed within-person stress generation effects, such that adolescents reported a greater number of dependent-interpersonal SLEs during time periods after experiencing higher levels of depression at the previous wave than was typical for them. While no within-person stress generation effects emerged for anxiety, higher overall levels of anxiety predicted greater exposure to dependent- interpersonal SLEs. Our findings extend prior work by demonstrating stress sensitization in predicting depression following normative forms of SLEs and stress generation effects for both depression and anxiety using a multi-level modeling approach. Clinical implications include an individualized approach to interventions.

Keywords: Stress sensitization, stress generation, depression, anxiety, adolescents

Introduction

Exposure to stressful life events (SLEs) is a robust predictor of internalizing psychopathology, including depression (Hammen, 2005; Harkness, Bruce, & Lumley, 2006) and anxiety (Espejo et al., 2007; McLaughlin et al., 2012). Adolescence involves not only higher levels of exposure to SLEs (Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989), but these experience are more tightly coupled with increases in negative affect (Larson & Ham, 1993) and psychopathology (Monroe, Rohde, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1999) than in other developmental periods. The associations between SLEs and internalizing psychopathology are complex, with bidirectional influences and cascading effects over time (e.g., Hankin & Abramson, 2001). Stress generation is well documented in adolescents, such that the presence of internalizing psychopathology is associated with greater likelihood of experiencing SLEs that are generated, at least in part, by the adolescent (Hammen, 1991, 2005; Rudolph, 2008). Stress sensitization effects have also been observed during this period, such that exposure to stressors earlier in development heightens vulnerability for depression and anxiety following later stressors (Espejo et al., 2007; Hammen, Henry, & Daley, 2000). However, the vast majority of previous research on stress sensitization and generalization related to internalizing psychopathology in adolescents has relied on between-person approaches that compare average levels of stress across individuals in a sample. Between-person approaches are at odds with theoretical models of stress and psychopathology, which focus on within-person effects such as how stress and psychopathology are related within a given individual (Curran & Bauer, 2011). In other words, these approaches confound individual differences in who is exposed to stress with the predictors and outcomes of occasions when individuals are exposed. The present study addressed this limitation by utilizing a multi-wave, prospective design to investigate the dynamic interplay between SLEs and internalizing psychopathology over time during adolescence.

The stress sensitization hypothesis proposes that exposure to adversity early in development heightens vulnerability for developing depression and anxiety following subsequent stressors (Hammen, 2005; Hammen et al., 2000). Exposure to adversity early in development is associated with heightened emotional reactivity at neural (Hein & Monk, 2017; McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves, & Sheridan, 2015), psychophysiological (Lambert, King, Monahan, & McLaughlin, 2017; Starr et al., 2017), and behavioral measures (Heleniak, Jenness, Vander Stoep, McCauley, & McLaughlin, 2016; Lambert et al., 2017). A wide range of emotion regulation difficulties, ranging from attentional deployment (Pollak & Tolley-Schell, 2003) to emotional stimuli to engagement in high levels of maladaptive regulation strategies like rumination (Heleniak et al., 2016), have also been observed among those who have experienced early-life adversity. These alterations in emotional reactivity and regulation following chronic exposure to stress have been posited as a mechanism underlying stress sensitization effects by increasing the intensity and duration of emotional responses to subsequent SLEs. In a seminal study, Hammen and colleagues (2000) demonstrated that lower levels of exposure to SLEs were more strongly associated with depression among females with a history of childhood adversity than those who had never encountered adversity. Subsequent studies have demonstrated a similar pattern, whereby adolescents and adults with a history of exposure to childhood adversity were more likely to develop depression and anxiety after experiencing SLEs (Espejo et al., 2007; Harkness et al., 2006; McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010; Rudolph & Flynn, 2007; Starr, Hammen, Conway, Raposa, & Brennan, 2014). Notably, while some of these studies have used a longitudinal design to examine the stress sensitization hypothesis (Espejo et al., 2007; Hammen et al., 2000; Rudolph & Flynn, 2007; Starr et al., 2014), all focused on between-person effects.

Several studies have utilized intense repeated-measures designs such as daily diaries or experience sampling methodology to examine the stress sensitization hypothesis in a within-person framework, demonstrating that adults with a history of child maltreatment exhibit greater negative affect in response to daily stress compared to those without a history of childhood adversity (Glaser, Van Os, Portegijs, & Myin-Germeys, 2006; Wichers et al., 2009). While informative, these studies focused on daily stress and affect over the course of several days, which does not allow for examination of links between SLEs and symptoms of psychopathology over a time frame more relevant to symptom development and disorder onset (i.e., weeks to months; (Hammen, 2005; Monroe & Reid, 2008). One recent study employing a within-person statistical approach and multi-wave design over 2.5 years demonstrated that adults with a history of emotional maltreatment developed greater depression symptoms following SLEs than those without a maltreatment history (Shapero et al., 2014). Studies utilizing multi-wave, prospective designs to determine whether the stress sensitization processes increase vulnerability to internalizing psychopathology following recent exposure to SLEs in children and adolescents are notably lacking. Furthermore, existing work has largely examined stress sensitization within the context of exposure to childhood adversity, ranging from child maltreatment (Harkness et al., 2006; McLaughlin, Conron, et al., 2010) to experiences like parental divorce and marital discord (Espejo et al., 2007; Hammen et al., 2000). The role that recent experiences of developmentally normative SLEs (e.g., bullying, failing a test, peer conflict) play in sensitizing adolescents to depression and anxiety following subsequent SLEs has rarely been examined. We do so in the current report.

In addition to stress sensitization work demonstrating the interplay between SLEs occurring at different points in development and internalizing psychopathology, extensive evidence supports a bidirectional association between exposure to SLEs and internalizing symptoms. Hammen’s (1991) seminal work on stress generation demonstrated that adult women with depression experienced more SLEs that are partly dependent upon an individual’s characteristics or behaviors (i.e., dependent SLEs) over time compared to women without psychopathology. Subsequent studies have replicated these findings among children and adolescents with high levels of depression and anxiety, particularly in the generation of dependent-interpersonal SLEs (e.g., Hammen & Brennan, 2001; McLaughlin & Nolen- Hoeksema, 2012; Rudolph, 2008; Shapero, Hankin, & Barrocas, 2013; Shih, Abela, & Starrs, 2009). Likely mechanisms of this association including personality traits (Kendler, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003), interpersonal difficulties (Bos, Bouhuys, Geerts, Van Os, & Ormel, 2006; Shih, Barstead, & Dianno, 2018), corumination (Hankin, Stone, & Ann Wright, 2010), and attachment style (Hankin, Kassel, & Abela, 2005) have also been investigated. However, the majority of stress generation studies in developmental samples have been cross-sectional (Hammen & Brennan, 2001; Starr et al., 2010), utilized two time-point designs (Shih et al., 2009), or relied on between-person statistical approaches (Rudolph, Flynn, Abaied, Groot, & Thompson, 2009; Starr et al., 2017). These approaches are unable to capture how within-person associations between stress and internalizing symptoms unfold over time; in other words, they cannot test the hypothesis that when a particular adolescent experiences higher levels of depression or anxiety symptoms, they are more likely to subsequently experience SLEs. Only one study, to our knowledge, has used multilevel modeling to demonstrate that within-person fluctuations in depression symptoms predict fluctuations in SLEs across 5 months in a community sample of youth (Shapero et al., 2013).

Bidirectional theories of stress-psychopathology associations, including stress sensitization and stress generation, involve hypotheses about within-person processes (Abela & Hankin, 2008). For example, stress generation theories hypothesize that when youth experience symptoms of anxiety and depression the likelihood that they will generate more SLEs in their lives. However, as previously noted, the majority of studies have employed between-person designs or statistical approaches in order to make inferences about these within-person processes, an error of inference referred to as the ecological fallacy (Blakely & Woodward, 2000; Curran & Bauer, 2011). Prior research has documented between person differences in the propensity to experience SLEs (King, Molina, & Chassin, 2008). Between-person differences in SLEs likely reflect relatively stable individual differences, such as neuroticism or exposure to poverty, that raise exposure to SLEs (Kendler et al., 2003); however, between-person study designs can only provide information about such individual differences. For instance, a person may report high levels of exposure to SLEs and meet criteria for depression, while another may report no recent SLEs or depressive symptoms, and this does not imply that either person is likely to experience more SLEs when they become depressed. By aggregating information across multiple assessments, within-person models can directly test the assumption that when a person experiences more depression symptoms, they are more likely to develop SLEs relative to periods when they experienced an absence of symptoms. Although within-person designs have been used to test hypotheses about the relation between stress and alcohol use (King, Molina, & Chassin, 2009), cognitive vulnerability (Abela & Hankin, 2011), and genetic factors (Hankin, Jenness, Abela, & Smolen, 2011; Hankin et al., in press), these designs and related analytic techniques have rarely been utilized in the stress sensitization and generation literatures.

Further, while previous stress-sensitization research has examined childhood adversity as a moderating influence on symptom development, there has been less focus on how normative stressors may influence the likelihood of experiencing increases in internalizing symptoms following subsequent SLEs. Therefore, there is a need to not only examine between- and within-person effects, but the interaction between the two when testing the stress sensitization hypothesis. This approach has clinical relevance, especially for individualizing mental health interventions care approaches. For example, it could be useful for a clinician to know whether a relative increase in SLEs would be more likely to lead to later symptom increases for a child who generally experiences high or low levels of stress. Indeed, in contrast to the stress sensitization pattern, other evidence suggests a diminishing impact of SLEs on the onset and persistence of psychopathology, such that the incremental effect of each additional SLE gets smaller as the number of exposures increases (Green et al., 2010; Kessler et al., 2010; McLaughlin, Green, et al., 2010). As previous work within the stress sensitization literature has not examined the interaction of between- and within-person effects of stress on psychopathology, this alternative has not yet been explored.

Adolescence is a key developmental period in which to investigate bidirectional models of stress and internalizing psychopathology. Indeed, most individuals experience their first onset of depression and anxiety during adolescence (Costello, Egger, & Angold, 2004; Hankin et al., 1998), and adolescent-onset depression and anxiety has been shown to substantially increase the risk for recurrence of internalizing disorders in adulthood (Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, 2006). Moreover, first-onsets of depression and anxiety are more closely tied to the experience of SLEs than subsequent, recurrent episodes (Chou, Mackenzie, Liang, & Sareen, 2011; Lewinsohn, Allen, Seeley, & Gotlib, 1999). Indeed, as many as half of all depression onsets in adolescence occur in the immediate aftermath of a stressor (Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, & Gipson, 2004; Monroe et al., 1999). Exposure to SLEs increases during the transition to adolescence, and stressors become more tightly coupled with increases in negative affect and changes in physiological reactivity (Gunnar, Wewerka, Frenn, Long, & Griggs, 2009; Larson & Ham, 1993; Stroud et al., 2009). Understanding the dynamic, bidirectional associations between SLEs and depression and anxiety symptoms across the transition to adolescence is of critical importance given the developmental changes in exposure and reactivity to SLEs that accompany the substantial increase in risk for depression and anxiety during this period.

The present study addressed several gaps in the stress sensitization and generation literatures in youth. We measured exposure to SLEs, depression, and anxiety symptoms every 3-months across 2 years in a large community-based sample of adolescents (aged 11–15 at baseline). We applied a novel test of the stress sensitization hypothesis by investigating whether vulnerability to anxiety and depression following SLEs was greater for adolescents who had higher or lower levels of exposure to SLEs on average across the two-year study period (i.e., an interaction of between- and within-person effects). This approach allowed us to test both the stress sensitization hypothesis, positing that youths with higher average levels of exposure to SLEs will be at greater risk for symptom development on months when they experience an increase in SLEs compared to their own average, and the competing hypothesis that youth with higher average levels of stress exposure will be less likely to develop symptoms on months characterized by increases in SLEs relative to youths with lower average levels of stress. To examine the bidirectional association between internalizing symptoms and stress, we tested for stress generation effects positing that youths will be at greater risk for experiencing dependent-interpersonal SLEs on months when they experience an increase in depression or anxiety symptoms relative to their own average levels of symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited in Montreal, Quebec, Canada and Chicago, Illinois, United States through advertisements in local newspapers seeking participants for a study of adolescent development (see Abela & Hankin, 2011). The final sample consisted of 382 adolescents (59% girls) and one parent (79% mothers) aged 9 to 15 years-old (M=13.04, SD=1.11) at the baseline assessment. The Montreal and Chicago samples were comparable in terms of adolescent sex, grade, highest level of maternal and paternal education, and family income (ps>.05). The Chicago sample consisted of a greater proportion of ethnic minority youth, χ2(1)=17.36, p<.001, and youth from single-parent households χ2(1)=8.84, p<.01.

Procedures

The study consisted of a baseline laboratory assessment and then phone calls to complete questionnaire assessments every 3 months across 2 years following the initial assessment for a total of 9 measurement time-points. Anxiety symptoms were not assessed at baseline, so our analyses focused on the second through ninth waves of assessment (hereafter referred to as waves 1 through 8) for a total of 8 time-points. Youth and a parent completed questionnaires assessing the youth’s symptoms of depression and anxiety and experience of SLEs at each time point. As reported in Technow, Hazel, Abela & Hankin (2015), the average number of follow-up assessments completed by participants was 6.74 (SD=1.61). Non-Hispanic White youth completed more follow-ups (M=7.4, SD=.13) than other youth (M=6.1, SD=.22, t(345)=5.33, p<.01), and there was a moderate association between family income and completed follow-ups (r=.18, p<.01). The number of follow-up assessments completed was not significantly associated with youth’s age, sex, depression or anxiety symptoms, and SLE exposure at baseline (ps>.05).

Measures

Psychopathology.

Depression.

Depression symptoms were measured with the 27-item Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 2003). Youth were asked to report on depression symptoms occurring in the last 2 weeks. Items are scored from 0 to 2 with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The CDI has good reliability and validity (Craighead, Smucker, Craighead, & Ilardi, 1998) and excellent internal consistency across all time points in the current study (α=.87- .91).

Anxiety.

Anxiety symptoms were measured with the 39-item Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Sullivan, & Parker, 1999). Youth were asked to report on anxiety symptoms occurring in the last 3-months. Items are scored from 1 (Never) to 4 (Often) with higher scores indicating greater symptoms severity. The MASC has good reliability and validity (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The MASC demonstrated good internal consistency across all time points in the current study (α=.72-.75)

Stressful life events.

SLEs were measured with the 57-item Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire (ALEQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002). The ALEQ measures the occurrence of a broad range of negative events that typically occur among youth, including school, friendship, romantic, and family events. Youth were asked to report how often a stressor occurred within the last 3-months on a scale of 1 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always). We used the total ALEQ score for the stress sensitization analyses. Based on prior work on internalizing psychopathology and stress generation that has observed stress generation effects primarily in the interpersonal domain (Hammen, 2006; Liu & Alloy, 2010; Rudolph, 2008), we calculated a dependent-interpersonal ALEQ score for stress generation analyses (see Supplement and Hankin et al., 2010 for a full description of item coding methods). Scores were summed with higher scores indicating greater frequency of SLEs for both total and dependent-interpersonal ALEQ variables.

Statistical Approach

We were interested in examining 1) between- and within-person effects of SLEs on the trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms (i.e., stress sensitization effects) and 2) between- and within-person effects of depression and anxiety symptoms on the trajectory of SLEs (i.e., stress generation effects) across 2-years (8 waves of data). We used multilevel models (MLM) to examine these aims because they estimate parameters using all available Level 1 data (i.e., repeated assessments of participants over time), do not require all participants to have identical or balanced observations at Level 1, and permit examination of between- and within-person components of variance (and their interaction) in predictors and outcomes (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). We tested our hypotheses in R 3.3.1 using the package ‘lme4’ version 1.1–18-1 (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2014). Model comparison was conducted using the maximum likelihood estimator (ML) to allow for comparison of models with different fixed effects specifications; final presented models estimated with restricted maximum likelihood estimator (REML) to reduce bias in random effects estimations (Tom, Bosker, & Bosker, 1999)1.

To separate the between- and within-person effects in stress sensitization and stress generation models, we used within-individual centering (i.e., centering each participant’s observations at Level 1 around their person-specific mean across the 2-year study period) and grand-mean centering at Level 2 (i.e., centering each participant’s mean level for the entire study period relative to the overall mean for the entire sample) for all predictors (i.e., total SLEs for stress sensitization and anxiety or depression symptoms for stress generation models). This approach entirely partitions variation in a given predictor into between- and within-person variability (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Additionally, we mean centered age and time so all intercept analyses are referring to the mean age of the sample (i.e., 13.04) and the midpoint of the study (i.e., between waves 4 and 5), respectively. At each time point, stress and anxiety were assessed over the past three months, and depression over the last two weeks. To model prospective stress generation, depression and anxiety at the previous wave (i.e., 3 months earlier) were entered as predictors of current SLEs in stress generation models.

We examined stress sensitization and stress generation effects separately in depression and anxiety. While there is high diagnostic comorbidity between depression and anxiety across the lifespan (Kessler et al., 2003), several multi-wave longitudinal studies have demonstrated that depression and anxiety can be partitioned into both shared and unique components with distinct trajectories as opposed to being represented by a single underlying internalizing factor (Fergusson, Horwood, & Boden, 2006; Olino, Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 2008, 2010).

Model fitting approach.

We followed a standard model fitting approach. For all model comparisons we used −2 log likelihood and AIC and BIC as tests of relative model fit (Raftery, 1995). We first estimated unconditional growth models for outcome variables (i.e., depression and anxiety symptoms or SLEs) to determine the shape of change over time, comparing different time functions and testing for random effects of time. Next we examined main effects of covariates (age and gender) on each outcome. In the stress sensitization models, we then examined the effects of between- and within-person SLEs on anxiety and depression symptoms. Finally, we tested the interaction of between- and within-person effects of SLEs on anxiety and depression symptom outcomes. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that within-person increases in SLEs (i.e., greater SLE exposure at a given point in time relative to one’s mean level of SLE exposure) would be associated with greater depression and anxiety symptoms among youth who experience higher levels of SLEs on average than among youth with lower mean levels of exposure to SLEs. Stress generation models were similarly tested, but with between- and within-person main effects of anxiety and depression symptoms as predictors of SLEs. We hypothesized that youths who experienced an increase in depression or anxiety symptoms relative to their own average level of symptoms would be significantly more likely to report exposure to SLEs at that time point.

As recommended best practice for regression model building (Allison, 1977), we tested all covariate by predictor interactions to ensure that our primary analyses of interest were not biased by unmodeled dependencies in the data2. Specifically, simulations have demonstrated that neglecting to include or estimate interactions in models can induce substantial bias in the main effects of coefficients (Vatcheva, Lee, McCormick, & Rahbar, 2015). We refrained from interpreting any interactions to avoid capitalizing on chance and non-hypothesized effects.

In the service of transparency and reproducibility, we provide the statistical code used to generate all MLM analyses and the output as a Supplement to the paper. Details of model validation can be found in Supplement.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The distribution of depression and anxiety symptoms and frequency of SLEs across the 8 waves of data are presented in Figure 1. The correlation between demographic covariates, SLEs and depression and anxiety symptoms is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Unconditional growth models. Depression and anxiety symptoms and stressful life events (total and dependent-interpersonal) over time. Note. Dep. Int. Stress=Dependent-Interpersonal Stress.

Table 1.

Correlations between primary demographic variables and depression and anxiety symptoms and SLEs across all time points.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression T1 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Depression T2 | .76** | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Depression T3 | .67** | .77** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Depression T4 | .59** | .63** | .74** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Depression T5 | .56** | .58** | .63** | .64** | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Depression T6 | .56** | .59** | .59** | .57** | .64** | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Depression T7 | .49** | .56** | .56** | .53** | .56** | .66** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Depression T8 | .30** | .26** | .38** | .33** | .42** | .46** | .33** | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Anxiety T1 | .39** | .40** | .43** | .41** | .32* | .33* | .34** | .26* | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.Anxiety T2 | .32** | .39** | .47** | .41** | .40** | .43** | .40** | .32** | .66** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Anxiety T3 | .30** | .38** | .42** | .42** | .36** | .32** | .30** | .23** | .70** | .76** | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Anxiety T4 | .30** | .36** | .41** | .47** | .37** | .37** | .33** | .28** | .56** | .70** | .71** | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.Anxiety T5 | .29** | .35** | .36** | .39** | .40** | .43** | .35** | .30** | .49** | .64** | .67** | .63**` | - | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 14.Anxiety T6 | .20** | .29** | .32** | .29** | .28** | .42** | .25** | .30** | .60** | .65** | .67** | .59** | .69** | - | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Anxiety T7 | .24** | .36** | .38** | .35** | .33** | .42** | .33** | .36** | .53** | .61** | .65** | .67** | .66** | .70** | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| 16.Anxiety T8 | .22* | .26** | .29** | .26* | .26* | .39** | .31** | .41** | .51** | .69** | .72** | .71** | .59** | .77** | .78** | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| 17.Total SLEs T1 | .58** | .51** | .44** | .36** | .45** | .40** | .39** | .18** | .34** | .29** | .18* | .26** | .20** | 0.1 | .21** | 0.12 | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 18.Total SLEs T2 | .57** | .67** | .61 ** | .50** | .52** | .50** | .49** | .24** | .33** | .44** | .30** | .33** | .32** | .26** | .30** | .27** | .71** | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 19.Total SLEs T3 | .46** | .59** | .70** | .59** | .56** | .48** | .49** | .30** | .43** | .51** | .44** | .40** | .42** | .35** | .40** | .33** | .59** | .71** | - | |||||||||||||||

| 20.Total SLEs T4 | .40** | .44** | .49** | .69** | .49** | .42** | .45** | .24** | .26* | .41** | .31** | .43** | .41** | .30** | .33** | 0.18 | .54** | .60** | .72** | - | ||||||||||||||

| 21.Total SLEs T5 | .46** | .47** | .49** | .52** | .70** | .53** | .47** | .37** | .25* | .36** | .34** | .35** | .46** | .37** | .36** | .33** | .54** | .61** | .63** | .61** | - | |||||||||||||

| 22. Total SLEs T6 | .41** | .45** | .46** | .47** | .56** | .73** | .54** | .35** | .27* | .44** | .35** | .35** | .44** | .45** | .34** | .37** | .48** | .58** | .64** | .63** | .68** | - | ||||||||||||

| 23.Total SLEs T7 | .36** | .48** | .47** | .48** | .46** | .53** | .69** | .28** | .33** | .47** | .30** | .35** | .43** | .37** | .42** | .26* | .53** | .62** | .66** | .66** | .64** | .70** | - | |||||||||||

| 24.Total SLEs T8 | .29** | .26** | .30** | .24** | .29** | .29** | .27** | .64** | 0.22 | .38** | .22** | .32** | .30** | .24** | .34** | .39** | 31** | .37** | .38** | .33** | .42** | .43** | .42** | - | ||||||||||

| 25.DI SLEs T1 | .34** | .24** | .30** | .20* | .33* | .17** | .14* | .37** | .37** | .33** | .18* | .27** | .22** | 0.12 | .23** | 0.17 | .70** | .44** | .40** | .39** | .43** | .25** | .32** | .49** | - | |||||||||

| 26.DI SLEs T2 | .35** | .38** | .37** | .31** | .36** | .25** | .22** | .43** | .32** | .46** | .29** | .34** | .33** | .27** | .32** | .32** | .43** | .64** | .48** | .40** | .47** | 0.31 | .36** | .49** | .68** | |||||||||

| 27.DI SLEs T3 | .32** | .37** | .44** | .41** | .39** | .27** | .23** | .46** | .42** | .52** | .46** | 0.41** | .42** | .37** | .41** | .39** | .39** | .50** | .73** | .56** | .53** | .38** | .45** | .52** | .60** | .71** | - | |||||||

| 28.DI SLEs T4 | .31** | .33** | .41** | .53** | .44** | .31** | .34** | .43** | .26** | .40** | .32** | .42** | .40** | .29** | .32** | .21* | .48** | .52** | .67** | .89** | .62** | .56** | .63** | .58** | .57** | .62** | .75** | - | ||||||

| 29.DI SLEs T5 | .47** | .44** | .45** | .48** | .60** | .51** | .54** | .52** | .23* | .35** | .32** | .35** | .43** | .38** | .38** | .34** | .56** | .64** | .69** | .69** | .89** | .70** | .72** | .68** | .57** | .67** | .69** | .74** | ||||||

| 30.DI SLEs T6 | .35** | .33** | .39** | .37** | .37** | .51** | .30** | .48** | .26** | .46** | .36** | .34** | .43** | .48** | .36** | .43** | .35** | .49** | .54** | .56** | .58** | .72** | .55** | .65** | .51** | .61** | .71** | .68** | .77** | - | ||||

| 31.DI SLEs T7 | .25** | .29** | .32** | .32** | .36** | .35** | .40** | .49** | .27** | .47** | .29** | .35** | .41** | .37** | .42** | .27** | .39** | .45** | .54** | .58** | .54** | .56** | .80** | .66** | .53** | .62** | .67** | .72** | .78** | .74** | - | |||

| 32.DI SLEs T8 | .47** | .42** | 44** | .48** | .45** | .46** | .43** | .64** | 0.21 | .38** | .25** | .32** | .31** | .25** | .35** | .42** | .46** | .60** | .60** | .57** | .70** | .68** | .72** | .96** | .46** | .61** | .62** | .56** | .73** | .68** | .74** - | |||

| 33.AgeTl | .13* | 0.10 | .17* | .19** | .18* | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | .20** | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | .11* | .15** | .21** | .21** | .14* | .13* | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.19** | .21** | .22** | .22** | .23** | .18** | .18** | - | |

| 34.Sex | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .12* | 0.17 | 0.16 | .25* | .24** | .21** | .15* | .26** | 0.18 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | - |

Note. SLEs=Stressftil Life Events; Dl= Dependent-interpersonal; Tl= Time 1;

p<.01,

p<.05

Unconditional Models

Unconditional growth models for depression and anxiety symptoms and dependent- interpersonal SLEs are presented in Supplement (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Unconditional growth models for depression and anxiety symptoms and stressful life events (SLEs)

| Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.12 | 0.557 |

| Linear Time | −0.01 | 0.008 | −0.03 | 0.005 | 0.178 |

| Quadratic Time | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.009 | 0.003 | 0.331 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.67 | 0.82 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.01 | 0.11 | |||

| Quadratic Time | 0.001 | 0.03 | |||

| Residual | 0.36 | 0.60 | |||

| Anxiety | |||||

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.820 |

| Linear Time | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.03 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.63 | 0.79 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.006 | 0.08 | |||

| Residual | 0.32 | 0.57 | |||

| Dependent-Interpersonal SLEs | |||||

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.13 | 0.425 |

| Linear Time | −0.01 | 0.007 | −0.02 | 0.008 | 0.382 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.69 | 0.83 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.01 | 0.08 | |||

| Residual | 0.30 | 0.55 | |||

Note. SLEs= Stressful Life Events; Depression measured with the Children’s Depression Inventory; Anxiety measured with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; SLEs measured with the Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire.

Stress Sensitization

Main Effects of Stressful Life Events Predicting Depression Symptoms.

We examined the between- and within-person associations of SLEs with depression symptoms over time, predicting the intercept and growth of depression symptoms from between- and within-person variability in exposure SLEs. The best fitting model demonstrated significant within- (β=.31, SE=.01, p<.001) and between-person (β=.62, SE=.03, p<.001) associations of SLEs with the level of depression symptoms at the mid-point of the study (but not the linear or quadratic effect of time), as well as an interaction between within-person SLEs and the linear effect of time (β=.03, SE=.005, p<.001). In other words, adolescents who experienced a higher average number of SLEs had higher levels of depression symptoms than adolescents who had a lower average number of SLEs (between-person effect), but exhibited no differences in the rate of change in depression symptoms over time. Moreover, the within-person association between SLEs and depression symptoms increased over time (within-person effects). There were no significant effects of between-person SLEs on linear or quadratic symptom growth and no effect of within-person SLEs on quadratic symptom growth; adding these terms to the model significantly worsened model fit across all indices.

Main Effects of Stressful Life Events Predicting Anxiety Symptoms.

We examined the between- and within-person associations of SLEs with anxiety symptoms over time, predicting the growth and level of anxiety symptoms from between- and within-person variability in the frequency of SLEs. The best fitting model included significant within-person (β=.21, SE=.02, p<.001) and between-person (β=.38, SE=.05, p<.001) associations of SLEs with anxiety symptoms. There were no significant interactions of between- or within-person SLEs on linear symptom growth; adding these terms to the model significantly worsened model fit across all indices.

Stress Sensitization Predicting Depression Symptoms.

We tested for stress sensitization effects in predicting depression symptoms by determining whether the association of within-person variability in SLEs on depression symptoms differed depending on the individual’s overall mean level of SLE across all 8 waves of data (i.e., between-person variability in SLEs). We tested this hypothesis by including a within-person SLE by between- person SLE interaction variable as a predictor of depression symptoms. Table 3 presents these final results and Figure 2 visualizes these findings. We found significant moderation of within-person SLEs by between-person SLEs such that individuals with higher overall levels of SLEs across the entirety of the study experienced more depression symptoms at time points when they reported greater SLEs compared to their own average (β=.02, SE=.01, p=.017) relative to adolescents who had lower average levels of SLEs over the study period.

Table 3.

Stress sensitization: Between and within-person SLEs predicting depression and anxiety symptoms (final models)

| Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.03 | 0.228 |

| Age | 0.008 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.767 |

| Sex | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.21 | 0.040 |

| Linear Time | −0.0003 | 0.007 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.970 |

| Quadratic Time | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.003 | 0.007 | 0.369 |

| Within-person SLEs | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Between-person SLEs | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.67 | <0.001 |

| Between-person SLEs X Within-person SLEs | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.017 |

| Linear Time*Within-person SLEs | 0.03 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.22 | 0.47 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.01 | 0.09 | |||

| Quadratic Time | 0.0002 | 0.01 | |||

| Residual | 0.27 | 0.52 | |||

| Anxiety | |||||

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | −0.18 | 0.07 | −0.32 | −0.05 | 0.013 |

| Linear Time | −0.04 | 0.009 | −0.06 | −0.02 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.525 |

| Sex | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Within-person SLEs | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Between-person SLEs | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.47 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.45 | 0.67 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.006 | 0.08 | |||

| Residual | 0.29 | 0.54 | |||

Note. SLEs= Stressful Life Events; Depression measured with the Children’s Depression Inventory; Anxiety measured with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; SLEs measured with the Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire.

Figure 2.

Stress sensitization effects. Effect of within-person centered (i.e., an individual’s month to month variation) stressful life events on depression and anxiety symptoms at different levels of grand mean centered stress (i.e., an individual’s average levels compared to the entire sample average). Annotated slopes were calculated by regressing the symptom levels predicted by the final models for each data point with within-person SLEs for each level of between-person SLEs.

Stress Sensitization Predicting Anxiety Symptoms.

We evaluated stress sensitization effects in predicting anxiety using the same approach (i.e., including a within-person SLE by between-person SLE interaction variable as a predictor of anxiety symptoms). We found no moderation of within-person variability by between-person variability in SLEs on anxiety symptoms (Figure 2) and the addition of this interaction to the model significantly worsened model fit across all indices. Therefore, we removed the interaction term from the final model, and Table 3 presents these results.

Stress Generation

Depression Symptoms Predicting Stressful Life Events.

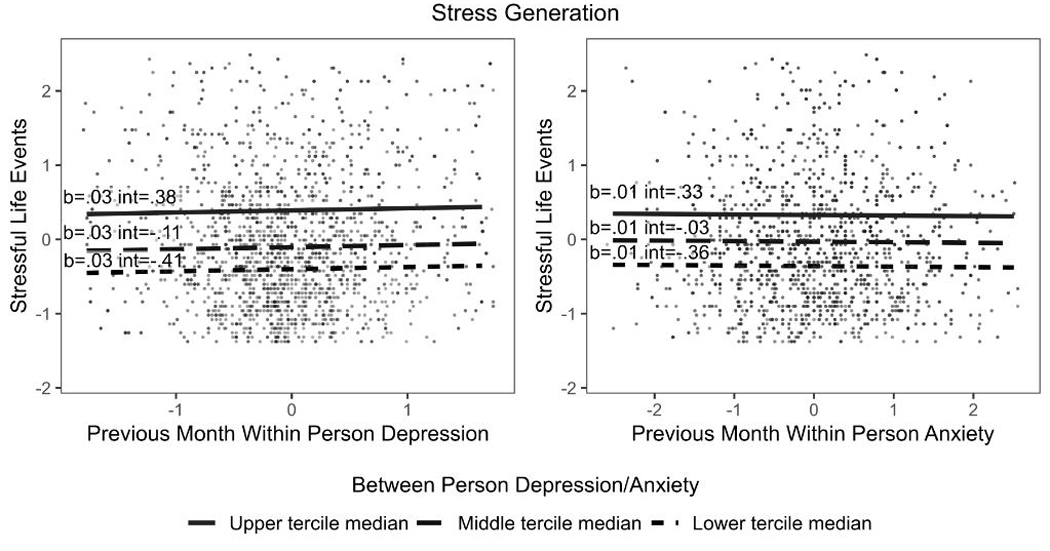

We added the main effects of between-person depression and within-person deviations in depression symptoms from the previous wave as well as interactions with all other predictors to predict dependent-interpersonal SLEs. The best fitting model included significant main effects of between-person depression (β=.42, SE=.04, p<.001) and within-person depression assessed at the prior wave (β=.03, SE=.02, p=.042) in predicting exposure to SLEs and a significant two-way interaction between linear time and within-person depression symptoms (β=−.03, SE=.009, p=.004). The interaction indicated that the association between within-person increases in depression symptoms at the previous wave and exposure to dependent-interpersonal SLEs was strongest at the beginning of the study and became weaker over time (Supplemental Figure 1). Table 4 presents the final results and Figure 3 visualizes the hypothesized main effect of between- and within-person depression symptoms in predicting greater SLEs.

Table 4.

Stress generation effects: Depression and anxiety symptoms predicting dependent-interpersonal SLEs (final models)

| Depression Predicting SLEs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | −0.007 | 0.06 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.913 |

| Age | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.005 |

| Sex | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.23 | 0.448 |

| Linear Time | −0.01 | 0.008 | −0.03 | 0.007 | 0.252 |

| Within-person Depression | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.042 |

| Between-person Depression | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Linear Time X Within-person Depression | −0.03 | 0.009 | −0.04 | −0.008 | 0.004 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.53 | 0.73 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.009 | 0.09 | |||

| Residual | 0.27 | 0.52 | |||

| Anxiety Predicting SLEs | |||||

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | LCL | UCL | p |

| Intercept | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.20 | 0.470 |

| Age | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −0.13 | 0.09 | −0.31 | 0.06 | 0.180 |

| Linear Time | −0.009 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.388 |

| Within-person Anxiety | 0.002 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.890 |

| Between-person Anxiety | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.47 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | |||

| Intercept | 0.53 | 0.73 | |||

| Linear Time | 0.01 | 0.10 | |||

| Residual | 0.21 | 0.46 | |||

Note. SLEs= Stressful Life Events; Depression measured with the Children’s Depression Inventory; Anxiety measured with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; SLEs measured with the Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire.

Figure 3.

Stress generation effects. Main effects of within-person centered (i.e., an individual’s month to month variation) and grand mean centered (i.e., an individual’s average levels compared to the entire sample average) depression and anxiety symptoms on stressful life event exposure. Note. Int=Intercept.

Anxiety Symptoms Predicting Stressful Life Events.

Similar to the depression and stress generation models, we systematically added the main effects of between-person and time-lagged within-person differences in anxiety symptoms as well as interactions with all other predictors to predict dependent-interpersonal SLEs. The best fitting model included significant main effects of between-person (β=.38, SE=.05, p<.001), but not within-person (β=.002, SE=.01, p=.890) differences in anxiety symptoms in predicting SLEs. Table 4 presents the final results and Figure 3 visualizes the main effect of between-person increases in anxiety symptoms predicting greater SLEs.

Discussion

Although theoretical models of the association between SLEs and internalizing psychopathology focus on within-person effects, previous research has primarily utilized crosssectional designs and between-person analytic methods. The present investigation addressed this gap, demonstrating cumulative and bidirectional associations between SLEs and symptoms of depression and anxiety in a 2-year prospective, multi-wave study of adolescents. Our results support and extend prior work on the stress sensitization hypothesis, demonstrating that the association between recent SLEs and depression symptoms is stronger among adolescents who experience higher average levels of SLEs. The stress sensitization effect was specific to within- person variation in SLEs, meaning that depression symptoms were more likely to occur on months when an adolescent experienced greater exposure to SLEs than was typical for them, with a stronger within-person association among adolescents with greater overall exposure to SLEs during the study period. We additionally extended prior work on stress generation that has largely relied on between-person approaches, demonstrating associations of within-person depression symptoms and dependent-interpersonal SLEs, such that adolescents reported a greater number of dependent-interpersonal SLEs after experiencing higher levels of depression symptoms at the previous wave than is typical for them, and this effect was strongest at the beginning of the study. We found evidence for between-person, but not within-person, effects of anxiety symptoms on the generation of dependent-interpersonal SLEs. All effects were robust to the inclusion of covariate (i.e., age and gender) by predictor interactions, replication with multiple imputation, and model validation using SEM-based latent growth models with structured residuals (Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane, & McGinley, 2014).

We provide novel evidence for the presence of stress sensitization effects in relation to normative SLEs occurring during adolescence. Specifically, we observed that depressive symptoms were higher on months when adolescents reported higher total SLEs than usual relative to their own average, and that this within-person association was significantly stronger among youth who had higher average levels of exposure to SLEs over the two-year study period. This finding is consistent with the prior stress sensitization literature (e.g., Hammen et al., 2000; McLaughlin, Conron, et al., 2010) and extends these prior findings in several important ways. First, while theoretical models of stress sensitization inherently require within-person statistical approaches, previous research in children and adolescents has almost exclusively utilized either cross-sectional designs (Harkness et al., 2006) or between-person statistical approaches with longitudinal data (Espejo et al., 2007; Starr et al., 2014). The present study provides an important test of the stress sensitization hypothesis using a within-person statistical approach. Second, previous stress sensitization research has been conducted largely in adults (Hammen, 2006; Hammen et al., 2000; McLaughlin, Conron, et al., 2010; Wichers, Schrijvers, Geschwind, Jacobs, Myin-Germeys, Thiery, Derom, Sabbe, Peeters, Delespaul, & van Os, 2009) or older adolescents (Shapero et al., 2014; Starr et al., 2014). The two studies among youth samples were either cross-sectional (Harkness et al., 2006) or two-time point designs (Espejo et al., 2007) that do not allow for examination of individual fluctuations in SLEs and symptoms over time. Finally, we examined stress sensitization following the experience of relatively normative forms of SLEs as opposed to more severe forms of adversity, like maltreatment or exposure to violence (Hammen et al., 2000; McLaughlin, Conron, et al., 2010). The present study makes an important contribution by expanding the stress sensitization framework to adolescents reporting less severe forms of SLEs and suggests that exposure to a wide range of stressors can heighten vulnerability to depression and anxiety following SLEs occurring at a later point in time. Identifying the mechanisms that underlie this type of stress sensitization, particularly utilizing within-person modeling approaches, is an important goal for future research.

While we found main effects for both between- and within-person SLEs predicting anxiety symptoms, we did not observe stress sensitization effects in relation to anxiety. This finding was contrary to our hypotheses and two previous studies examining stress sensitization in relation to childhood adversity and the association between SLEs and anxiety in adolescence (Espejo et al., 2007) and adulthood (Hammen et al., 2000; McLaughlin, Conron, et al., 2010). This discrepancy might be related to the type of stressors assessed across studies. Specifically, both previous studies investigated more severe forms of environmental adversity and major life events (i.e., parental death, child maltreatment) as opposed to the more normative types of SLEs examined here. While it is important to not over-interpret a null finding, the discrepancy between the present study and past research may suggest that stress sensitization processes in relation to anxiety are applicable only among individuals who have experienced severe adversities or major life events in childhood. Greater research is needed to explore this possibility in other samples.

We also examined whether the well-replicated bidirectional associations between SLEs and internalizing psychopathology from between-person designs would be observed in our within-subject approach. To do so, we evaluated whether adolescents reported an increased number of dependent-interpersonal SLEs after experiencing higher levels of depression or anxiety at the previous wave than was typical for them. We found evidence for this pattern of within-person stress generation for depression symptoms, and this effect was strongest earlier in the study period. While we did not observe within-person effects of anxiety symptoms on the generation of dependent-interpersonal SLEs, we did find between-person effects of anxiety symptoms. These findings are broadly consistent with the extant stress generation literature in adolescents examining between-person differences in anxiety (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012) and depression (Hammen, 2006; Rudolph et al., 2009) in predicting exposure to SLEs. These between-person differences likely reflect a variety of trait-like differences among adolescents who develop depression and anxiety relative to those that do not, including neuroticism (Kendler, Kuhn, & Prescott, 2004; Muris, Roelofs, Rassin, Franken, & Mayer, 2005). While there has been extensive replication of these between-person stress generation findings across the life-course, only one prior study utilized a within-subject approach to examine these associations in adolescents (Shapero et al., 2013), and this study was limited to a 5-month time frame with a sole focus on depression symptoms. Our findings that when adolescents experience greater levels of depressive symptoms than is typical for them they are more likely to generate interpersonal stressors in their lives, together with this prior study, highlight the importance of identifying mechanisms underlying these within-person associations. Several candidate mechanisms that likely fluctuate along with symptoms of depression include difficulties with interpersonal problem-solving (Davila, Hammen, Burge, Paley, & Daley, 1995), avoidant coping strategies (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Brennan, & Schutte, 2005), self-criticism (Shahar & Priel, 2003; Shih et al., 2009), and engagement in rumination and other maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (Kercher & Rapee, 2009; McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Future studies using prospective, multi-wave data are necessary to evaluate these potential within-person mechanisms.

Limitations of the current study include the use of self-report for measurement of depression and anxiety symptoms and exposure to SLEs over time. While self-report measures utilized in the present study were well-validated, reliable assessments of internalizing psychopathology symptoms and a broad range of SLEs typically experienced by youth and allow for more frequent, long-term assessment of constructs, the use of interview-based measures would have been preferable. This is particularly important when considering mood-related memory biases in the reporting of SLEs (Mineka & Nugent, 1995; Teasdale, 1983), shared method variance, intra-category variability (Dohrenwend, 2006) and distinguishing between SLE occurrence and psychopathology-related responses to SLEs (Harkness & Monroe, 2016), which are mitigated with the use of contextual threat interviews (i.e., Hammen & Rudolph, 1999). Relatedly, we aggregated the prospective self-report of SLEs to evaluate how between-person effects of SLE exposure function as a moderator in stress sensitization models as opposed to asking adolescents to retrospectively report their normative SLE exposure across the last few years at the first timepoint. This method makes an assumption that youth who experienced globally higher levels of SLEs over the two-year assessment period were likely to have also had higher rank-order exposure to SLEs prior to the study. While there is evidence for continuity over time in the rank-ordering of exposure to SLEs among children and adolescents (e.g., Hanson et al., 2010; Pearlin, 1989; Raposa, Hammen, Brennan, O’Callaghan, & Najman, 2014), it is unknown whether this is an accurate assumption without having retrospective measurements of past SLE experiences and may temper inferences that can be drawn from the present study. Further, our focus on internalizing symptoms limits our ability to draw conclusions about how stress sensitization and generation processes may relate to clinical levels of internalizing psychopathology. While many have advocated for dimensional approaches when assessing psychopathology in order to better assess severity, subclinical symptom presentations that may predict later disorder onset, and changes in symptoms over time (Kessler, 2002; Lebeau et al., 2012), the addition of a diagnostic assessment would strengthen clinical implications of future research. Finally, we examined stress sensitization and generation effects separately for depression and anxiety. Investigating the degree to which stress generation and sensitization processes are transdiagnostic across internalizing problems or specific to anxiety or depression remains an area for future research given the high diagnostic comorbidity, particularly at the symptom level (Kessler, 2003)

The present study advances understanding of stress sensitization and generation processes during adolescence by utilizing a prospective, multi-wave design and within-person analytical approach to examine cumulative and bidirectional associations between SLEs and internalizing psychopathology. We extend prior work on stress sensitization by documenting within-person sensitization effects following normative experiences of SLEs as compared to prior work examining severe forms of early adversity and between-person effects. Similarly, we document within-person stress generation effects, such that adolescents experiencing higher depression symptoms than is typical for them also reported higher levels of SLEs. Clinical implications of findings include the use of an individualized intervention approach in which adolescents may be at greater risk for symptom deterioration following particularly stressful months.

Supplementary Material

Stress generation depression by time interaction. Interaction of grand mean centered depression (i.e., an individual’s average levels compared to the entire sample average) and linear time on dependent-interpersonal stressful life event exposure.

General Scientific Summary.

This study demonstrates that adolescents who report more overall stress compared to others experience greater depression symptoms during months when their own stress level is higher than is typical for them. We also show that adolescents report greater exposure to interpersonal stressors that are partly dependent upon an individual’s characteristics or behaviors after months when they experience higher depression symptoms than is typical for them, while higher overall symptoms of anxiety predicted greater exposure to such stressors. This research suggests a two-way relationship between stress and symptoms of depression and anxiety and may help mental health professionals better understand how stress, depression, and anxiety are related within a particular individual.

Acknowledgments

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Montréal (“Cognitive Factors in Emotions during Adolescence”) and supported by research grants from the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression awarded to John R.Z. Abela; research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (Jenness: K23-MH112872; McLaughlin: R01-MH103291 and R01-MH106482; Hankin: R03-MH 066845) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention awarded to Benjamin L. Hankin.

Footnotes

Final models estimates were nearly identical when using ML instead of REML. Summaries of our final models as estimated by ML are included in the Supplement.

Results were virtually unchanged when adding covariate by predictor interactions into final models.

References

- Abela JRZ, & Hankin BL (2008). Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective In Abela JRZ & Hankin BL (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. (pp. 35–78). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. (2008–01178-003). [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, & Hankin BL (2011). Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(2), 259–271. 10.1037/a0022796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD (1977). Testing for interaction in multiple regression. American Journal of Sociology, 53(1), 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D,Mächler M,Bolker B,& Walker S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1406.5823. [Google Scholar]

- Blakely TA, & Woodward AJ (2000). Ecological effects in multi-level studies. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 54(5), 367–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos EH, Bouhuys AL, Geerts E,Van Os TW, & Ormel J. (2006). Lack of association between conversation partners’ nonverbal behavior predicts recurrence of depression, independently of personality. Psychiatry Research, 142(1), 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K-L, Mackenzie CS, Liang K,& Sareen J. (2011). Three-year incidence and predictors of first-onset of DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in older adults: Results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger HL, & Angold A. (2004). Developmental Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2004-00147-003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 583–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Howard AL, Bainter SA, Lane ST, & McGinley JS (2014). The separation of between-person and within-person components of individual change over time: a latent curve model with structured residuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J,Hammen C,Burge D,Paley B,& Daley SE (1995). Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(4), 592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP (2006). Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Tofighi D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, & Bor W. (2007). Stress sensitization and adolescent depressive severity as a function of childhood adversity: A link to anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(2), 287–299. 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, & Boden JM (2006). Structure of internalising symptoms in early adulthood. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 189(6), 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser J-P, Van Os J,Portegijs PJ, & Myin-Germeys I. (2006). Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(2), 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, & Gipson PY (2004). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Measurement issues and prospective effects. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(2), 412–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Wewerka S,Frenn K,Long JD, & Griggs C. (2009). Developmental changes in hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal activity over the transition to adolescence: normative changes and associations with puberty. Development and Psychopathology, 21(01), 69–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C,& Rudolph K. (1999). UCLA life stress interview for children: Chronic stress and episodic life events Manual. University of Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen Constance. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen Constance. (2005). Stress and Depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 293–319. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen Constance. (2006). Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(9), 1065–1082. 10.1002/jclp.20293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen Constance, & Brennan PA (2001). Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: Tests of an Interpersonal Impairment Hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(2), 284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen Constance, Henry R,& Daley SE (2000). Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 782–787. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, & Abramson LY (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R,& Angell KE (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Jenness J,Abela JR, & Smolen A. (2011). Interaction of 5-HTTLPR and idiographic stressors predicts prospective depressive symptoms specifically among youth in a multiwave design. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 572–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Kassel JD, & Abela JR (2005). Adult attachment dimensions and specificity of emotional distress symptoms: Prospective investigations of cognitive risk and interpersonal stress generation as mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Stone L,& Ann Wright P. (2010). Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: Accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multi wave study of adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 22(01), 217–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Young JF, Smolen A,Jenness JL, Gulley LD, Technow JR, ... Oppenheimer CW (in press). Depression from childhood into late adolescence: Influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Chung MK, Avants BB, Shirtcliff EA, Gee JC, Davidson RJ, & Pollak SD (2010). Early stress is associated with alterations in the orbitofrontal cortex: a tensor-based morphometry investigation of brain structure and behavioral risk. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(22), 7466–7472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Bruce AE, & Lumley MN (2006). The role of childhood abuse and neglect in the sensitization to stressful life events in adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(4), 730–741. 10.1037/0021-843X.115A730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, & Monroe SM (2016). The assessment and measurement of adult life stress: Basic premises, operational principles, and design requirements. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein TC, & Monk CS (2017). Research Review: Neural response to threat in children, adolescents, and adults after child maltreatment-a quantitative meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(3), 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heleniak C,Jenness JL, Vander Stoep A,McCauley E,& McLaughlin KA (2016). Childhood maltreatment exposure and disruptions in emotion regulation: A transdiagnostic pathway to adolescent internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(3), 394–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL, & Schutte KK (2005). Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, & Prescott CA (2003). Personality and the experience of environmental adversity. Psychological Medicine, 33(7), 1193–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn J,& Prescott CA (2004). The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(4), 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kercher A,& Rapee RM (2009). A test of a cognitive diathesis—stress generation pathway in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, ... Williams DR (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C. (2002). The categorical versus dimensional assessment controversy in the sociology of mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 171–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C., Berglund P,Demler O,Jin R,Koretz D,Merikangas KR, ... Wang PS (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Jama, 289(23), 3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Molina BS, & Chassin L. (2008). A state-trait model of negative life event occurrence in adolescence: Predictors of stability in the occurrence of stressors. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(4), 848–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Molina BS, & Chassin L. (2009). Prospective relations between growth in drinking and familial stressors across adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert HK, King KM, Monahan KC, & McLaughlin KA (2017). Differential associations of threat and deprivation with emotion regulation and cognitive control in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 29(3), 929–940. 10.1017/S0954579416000584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R,& Ham M. (1993). Stress and” storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 130. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeau RT, Glenn DE, Hanover LN, Beesdo-Baum K,Wittchen H-U, & Craske MG (2012). A dimensional approach to measuring anxiety for DSM-5. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(4), 258–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Allen NB, Seeley JR, & Gotlib IH (1999). First onset versus recurrence of depression: differential processes of psychosocial risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(3), 483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, & Alloy LB (2010). Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), 582–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, & Gilman SE (2010). Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine, 40(10), 1647–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication II: associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2012). Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(11), 1151–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2012). Interpersonal stress generation as a mechanism linking rumination to internalizing symptoms in early adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(5), 584–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Peverill M,Gold AL, Alves S,& Sheridan MA (2015). Child maltreatment and neural systems underlying emotion regulation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(9), 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S,& Nugent K. (1995). Mood-congruent memory biases in anxiety and depression. Memory Distortions: How Minds, Brains, and Societies Reconstruct the Past, 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, & Reid MW (2008). Gene-environment interactions in depression research genetic polymorphisms and life-stress polyprocedures. Psychological Science, 19(10), 947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Rohde P,Seeley JR, & Lewinsohn PM (1999). Life events and depression in adolescence: relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset of major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(4), 606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P,Roelofs J,Rassin E,Franken I,& Mayer B. (2005). Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(6), 1105–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P,& Seeley JR (2008). Longitudinal associations between depressive and anxiety disorders: a comparison of two trait models. Psychological Medicine, 38(3), 353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P,& Seeley JR (2010). Latent trajectory classes of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence to adulthood: descriptions of classes and associations with risk factors. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51(3), 224–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, & Tolley-Schell SA (2003). Selective attention to facial emotion in physically abused children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(3), 323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Raposa EB, Hammen CL, Brennan PA, O’Callaghan F,& Najman JM (2014). Early adversity and health outcomes in young adulthood: The role of ongoing stress. Health Psychology, 33(5), 410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD (2008). Developmental influences on interpersonal stress generation in depressed youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(3), 673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, & Flynn M. (2007). Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Development and Psychopathology, 19(02), 497–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M,Abaied JL, Groot A,& Thompson R. (2009). Why is past depression the best predictor of future depression? Stress generation as a mechanism of depression continuity in girls. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(4), 473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M,Kim-Cohen J,& Maughan B. (2006). Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 276–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G,& Priel B. (2003). Active vulnerability, adolescent distress, and the mediating/suppressing role of life events. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(1), 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero BG, Black SK, Liu RT, Klugman J,Bender RE, Abramson LY, & Alloy LB (2014). Stressful Life Events and Depression Symptoms: The Effect of Childhood Emotional Abuse on Stress Reactivity: Child Emotional Abuse and Stress Sensitization. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 209–223. 10.1002/jclp.22011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapero BG, Hankin BL, & Barrocas AL (2013). Stress generation and exposure in a multi-wave study of adolescents: Transactional processes and sex differences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(9), 989–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Abela JR, & Starrs C. (2009). Cognitive and interpersonal predictors of stress generation in children of affectively ill parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(2), 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Barstead MG, & Dianno N. (2018). Interpersonal predictors of stress generation: Is there a super factor? British Journal of Psychology, 109(3), 466–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Dienes K,Stroud CB, Shaw ZA, Li YI, Mlawer F,& Huang M. (2017). Childhood adversity moderates the influence of proximal episodic stress on the cortisol awakening response and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 29(5), 1877–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Hammen C,Conway CC, Raposa E,& Brennan PA (2014). Sensitizing effect of early adversity on depressive reactions to later proximal stress: Moderation by polymorphisms in serotonin transporter and corticotropin releasing hormone receptor genes in a 20-year longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology, 26(4pt2), 1241–1254. 10.1017/S0954579414000996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starrs CJ, Abela JR, Shih JH, Cohen JR, Yao S,Zhu XZ, & Hammen CL (2010). Stress generation and vulnerability in adolescents in mainland China. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(4), 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Starrs CJ, Abela JRZ, Zuroff DC, Amsel R,Shih JH, Yao S,... Hong W. (2017). Predictors of Stress Generation in Adolescents in Mainland China. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(6), 1207–1219. 10.1007/s10802-016-0239-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Foster E,Papandonatos GD, Handwerger K,Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, & Niaura R. (2009). Stress response and the adolescent transition: Performance versus peer rejection stressors. Development and Psychopathology, 21(01), 47–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD (1983). Negative thinking in depression: Cause, effect, or reciprocal relationship? Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 5(1), 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tom AB, Bosker TASRJ, & Bosker RJ (1999). Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Vatcheva KP, Lee M,McCormick JB, & Rahbar MH (2015). The effect of ignoring statistical interactions in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies: an example with survival analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression model. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale, Calif.), 6(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M,Schrijvers D,Geschwind N,Jacobs N,Myin-Germeys I,Thiery E,... others. (2009). Mechanisms of gene-environment interactions in depression: evidence that genes potentiate multiple sources of adversity. Psychological Medicine, 39(7), 1077–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M,Schrijvers D,Geschwind N,Jacobs N,Myin-Germeys I,Thiery E,... van Os J. (2009). Mechanisms of gene-environment interactions in depression: evidence that genes potentiate multiple sources of adversity. Psychological Medicine, 39(07), 1077 10.1017/S0033291708004388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials