Abstract

Purpose.

This research examined whether experiencing physical teen dating violence (TDV) relates to trauma symptoms, which in turn, predict future physical dating violence victimization in early adulthood.

Methods.

Adolescents (N=843) recruited from high schools reported on their experiences of physical TDV victimization and trauma symptoms. The sample was followed over a 5-year period to assess for re-victimization in early adulthood.

Results.

Trauma symptoms functioned as a mediator between experiences of physical TDV victimization during adolescence and later re-victimization in early adulthood, even in a conservative test of mediation that controlled for baseline trauma symptoms. Multi-group analyses testing for gender differences suggest this mediation model is significant for females, but not for males.

Conclusions.

The present findings suggest the mental health consequences of experiencing physical TDV are an important factor contributing to future victimization in early adulthood. This holds potentially important implications for school-based efforts for reducing physical TDV. Specifically, school-based efforts to reduce victimization may be enhanced by supplementing existing efforts with empirically-supported programs for addressing trauma symptoms.

Keywords: dating violence, trauma, victimization, re-victimization

US national surveys indicate that at least 10% of adolescents experience physical teen dating violence (TDV) over the course of a year [1-2]. Of those victimized, over 30% report continued victimization, spanning from adolescence into early adulthood [3]. Indeed, the association between experiencing physical TDV and being victimized again has been documented in over a dozen longitudinal studies, several of which have linked victimization during adolescence to victimization in early adulthood [4-7]. Experiencing physical TDV increases risk for a wide range of health problems, and re-victimization adds to this risk [8]. Thus efforts to understand and stop this recurring process are critical.

Trauma symptoms are one of the most common consequences of experiencing partner violence [9], and theory implicates trauma symptoms as a factor contributing to recurring victimization [10-11]. Trauma symptoms, for example, may interfere with the ability to perceive risk for violence accurately and respond adaptively. Specifically, victimized individuals with trauma symptoms may fail to notice, ignore, or downplay signs of danger in their relationships [12]. They may be more likely to enter into or remain in unhealthy relationships, perhaps feeling unworthy or unable to attract a more suitable partner [13]. Additionally, trauma symptoms might interfere with help-seeking efforts and the effective use of available resources (e.g., one’s social network) to prevent future incidents of violence [14].

Longitudinal research on the role of trauma symptoms in the re-victimization process for teens in romantic relationships is unfortunately sparse. However, a handful of prospective studies in adult populations point to trauma symptoms as a predictor of repeat victimization by a romantic partner. Specifically, among adult women who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), trauma symptoms prospectively relate to re-victimization [12, 14]. Further, in research examining pathways of victimization from childhood maltreatment to TDV victimization, trauma symptoms are often implicated [15]. These findings converge to suggest that trauma symptoms increase the likelihood of future victimization from a romantic partner.

The present research provides the first rigorous test of the hypothesis that trauma symptoms mediate the longitudinal association between physical TDV and later physical violence victimization in early adulthood. Prior research has tested circumscribed parts of this hypothesized mediation model, but the full longitudinal mediation model has not yet been evaluated. Based on theory and research with adult samples, we expect TDV victimization to predict trauma symptoms, which in turn predict physical violence victimization in early adulthood. We examine this hypothesis in a sample of teens recruited from high schools, as opposed to a help-seeking sample, in an attempt to better inform school-based prevention efforts. Specifically, there are now a number of empirically-supported school-based programs designed to prevent relationship violence among teens (e.g., Safe Dates [16], Ending Violence [17], Fourth R [18]). To better inform such efforts, research is needed on pathways to TDV victimization and re-victimization that involve high-school samples.

We also explored whether the proposed mediation model operates differently for males and females. Because of the power (size and weight) imbalance that favors males in most heterosexual relationships [19], females may be at greater risk for heightened threat, fear, helplessness or horror as a result of partner violence – factors associated with the development of trauma symptoms. Additionally, Wekerle and colleagues [20] found trauma symptoms mediated the relation between childhood maltreatment and TDV victimization for females, but not for males. In the present research, we hypothesized that the mediation model would be especially pertinent for females.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The Institutional Review Board at the last author’s institution approved all procedures. Data for this research are from a study in which participants were assessed over a 5-year period on a range of health and risk behaviors [21]. In the spring of 2010, 9th and 10th grade students (n=1,042; response rate=62%) were recruited from required classes in seven Texas public high schools. Parental consent and student assent were obtained prior to baseline, and participants provided their own consent upon reaching the age of 18. At the baseline, 1-year, and 2-year follow-ups, (retention rate at 2-year follow-up: 86% of baseline participants), project staff administered surveys during regular school hours. At the 5-year follow-up (retention rate: 73% of baseline participants) students still in school completed paper-pencil surveys during regular school hours and those who had moved on from high school completed surveys online. Students received a $10 gift card at the 1- and 2-year follow-up assessments (spring 2011 and 2012, respectively), and a $30 gift card at the 5-year follow-up assessment (spring 2015).

For the present study, we limited our analyses to youth who reported having been in a relationship at the 1-year follow-up (N=843, Female: 57%). Participants (mean age=16.09, SD=0.79, at baseline) were ethnically diverse: Hispanic (32%), White (31%), African American (27%), or other (10%). Participants reported parent education (highest of either parent) as: finished college (36%), some college/training school (30%), finished high school (17%), or did not graduate from high school (17%). At the 5-year follow-up, most participants were enrolled in some type of college (63%), with the remaining sample either working (30%) or not in school and not working (7%).

Measures

Physical Dating Violence Victimization (1- and 5-year follow-ups).

Participants reported the occurrence (0 = no, 1 = yes) of past-year physical dating violence victimization on four items adapted from the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationship Inventory (CADRI) [22]: “He/She threw something at me,” “He/She kicked, hit, or punched me,” “He/She slapped me or pulled my hair,” or “He/She pushed, shoved, or shook me.” Item scores were summed to create a scale score, with a higher score reflecting greater victimization (1-year follow-up: Cronbach’s α=.73, 5-year follow-up: Cronbach’s α=.81). Physical victimization at baseline was not used because only lifetime victimization was measured at that time point.

Trauma Symptoms (baseline and 2-year follow-up).

Using the 4-item Primary Care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD) [23], participants reported past-month presence (0=no, 1=yes) of trauma symptoms in response to any threatening or frightening lifetime event: e.g., “Had nightmares about it or thought about it when you did not want to?“ “Tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it?” “Were constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled?” “Felt numb or detached from others, activities, or your surroundings?” Items responses were summed (baseline: Cronbach’s α=.74; 2-year follow-up: Cronbach’s α=.82), with higher scores indicating more trauma symptoms.

Attrition Analyses

Participants who completed the 5-year follow-up did not differ significantly from those who did not on any demographics or study measure collected at baseline, 1-year follow-up, or 2-year follow-up, with two exceptions: younger participants, t(841)=2.91, p=.002, and females, χ2(1)=28.15, p<.001, were more likely than their counterparts to complete the 5-year follow-up.

Analytical Plan

We computed path analyses to test the hypothesized mediation model using Mplus 7.11 [24]. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was employed to handle missingness in longitudinal data [25], together with Maximum Likelihood with Robust standard errors (MLR) to deal with skewness of distributions [26-27]. This approach estimates all possible paths, which will always result in perfect fit. Thus, we do not report the fit indices here. The mediation model included TDV victimization at 1-year follow-up, trauma symptoms at 2-year follow-up, and physical violence victimization at 5-year follow-up. The model also included gender (0=male, 1=female); parental education (1=did not graduate from high school and 4=finished college); three dummy-coded ethnicity variables (e.g., White=1 vs. non-White=0, Hispanic=1 vs. non-Hispanic=0, Black=1 vs. non-Black=0); age at baseline (M=16.09, SD=0.79), and trauma symptoms at baseline (M=1.21, SD=1.36, Cronbach’s α=.74) as control variables in a model with the overall sample. To test gender differences, we computed a multi-group path analysis using the same model but excluded gender as a covariate.

Results

The prevalence of physical dating violence victimization (whether or not a victimization experience was reported) was 20% (males=18%; females=22%) at the 1-year follow-up and 20% (males=22%; females=18%) at the 5-year follow-up. These prevalence rates are comparable to those reported in national samples [1]. Prevalence rates for males and females did not differ significantly from each other at either time point. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Females experienced more acts of physical TDV than males at the 1-year follow-up, but not more acts of physical dating violence victimization at the 5-year follow-up. In addition, females reported more trauma symptoms than males at the 2-year follow-up.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Study Variables.

| Variables |

Overall Sample (N=843) |

Male (n=362) |

Female (n=481) |

df, t-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 1. Physical victimization at 1-yr fu | 0.36 | 0.85 | 0.29 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 836.7§, −2.35* |

| 2. Physical victimization at 5-yr fu | 0.40 | 0.95 | 0.48 | 1.07 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 408.8§, 1.65 |

| 3. Trauma symptoms at 2-yr fu | 1.20 | 1.47 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 1.44 | 1.50 | 749.0, −5.40*** |

| Correlation | |||||||

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 1. Physical victimization at 1-yr fu | 0.13 ** | 0.16*** | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.19 *** | 0.16*** | - |

| 2. Physical victimization at 5-yr fu | - | 0.18*** | - | 0.14* | - | 0.24*** | - |

| 3. Trauma symptoms at 2-yr fu | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note. Due to missingness each variable, df for each variable differed.

due to violation of the assumption of equality of variance, df was panelized.

p <.05

<.01

<.001

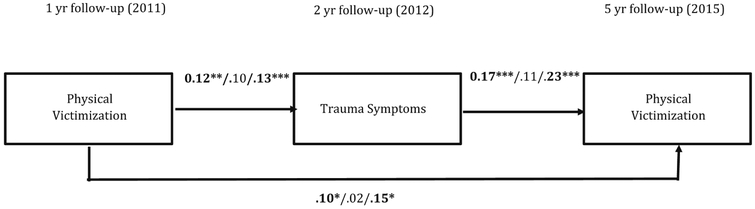

Our hypothesis that trauma symptoms would mediate the relation between physical dating violence victimization at the 1- and 5-year follow-ups was partially supported (see Figure 1). The model, when including all covariates and physical TDV victimization at the 1-year follow-up, explained 14% of the variance of trauma symptoms at the 2-year follow-up, and 7% of the variance of physical dating violence victimization at the 5-year follow-up. The model with the overall sample showed that trauma symptoms mediated the relation between physical dating violence victimization at the 1- and 5-year follow-up (ab=0.02, SE=0.01, p=0.01). That is, physical TDV at 1 year was positively related to trauma symptoms at 2 years (b=.20, se=0.06), which in turn was positively associated with physical dating violence victimization at 5 years (b=.11, se=0.30), after controlling for baseline trauma symptoms, gender, parental education, age, and ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Note. Path coefficients and correlations are standardized. Results for overall sample appear first, results for males appear second, and results for females appear third. Baseline trauma symptoms, gender, and three dummy-coded factors of ethnicity, age, and parental education were included as covariates in the model with the overall sample. In the multi-group path model, the same covariates except for gender were included. All significant (p < .05) paths are highlighted by boldface and marked by asterisks. * p < .05, ** < .01, *** < .001

Results of multi-group analyses testing for gender differences in the mediation model found that trauma symptoms functioned as a mediator for females but not for males (as before, baseline trauma symptoms, parental education, age, and ethnicity were included as control variables). For females, the model explained 14% of the variance in trauma symptoms at 2 years and 10% of the variance in physical dating violence victimization at the 5-year follow-up. Despite relatively small effect sizes, trauma symptoms mediated the relation between physical TDV at the 1-year follow-up (b=0.20, se=0.07) and physical dating violence victimization at 5 years (b=0.13, se=0.03).

For males, the model explained 9% of the variance in trauma symptoms at 2 years and 7% of the variance in physical dating violence victimization at the 5-year follow-up. For males, trauma symptoms at 2 years did not mediate the association between physical TDV victimization at 1 year and physical dating violence victimization at 5 years (ab=0.02, SE=0.02, p=.33). Specifically, physical TDV at the 1-year follow-up was not significantly related to trauma symptoms at the 2-year follow-up, b=0.20, se=0.14, p=.17, and trauma symptoms at 2-year follow-up were not significantly related to physical dating violence victimization at 5 years, b=.09. se=.06, p=.18.

Discussion

As hypothesized, trauma symptoms mediated the association between physical TDV victimization in adolescence and later victimization in early adulthood, even after controlling for baseline levels of trauma symptoms. When examining this model across genders, the mediation model held for females but not for males. The present findings are consistent with theoretical models implicating the mental health consequences of experiencing violence as a factor contributing to re-victimization over time [10-11]. Our results are also consistent with other longitudinal studies that suggest male and female adolescents often follow different developmental pathways to physical dating violence victimization [5, 28], as well as studies indicating that trauma symptoms predict future victimization among adolescents and adults [12, 14-15]. However, the present research extends prior empirical efforts by demonstrating in a longitudinal analysis that experiencing physical TDV during adolescence relates positively to trauma symptoms, which in turn predict physical violence victimization in early adulthood, even after accounting for baseline levels of trauma symptoms.

The present findings have potentially important implications for efforts to prevent physical dating violence victimization. Existing empirically-supported programs for TDV, which have been evaluated in high schools, focus on topics such as knowledge of the legal ramifications of dating violence, how to recognize abusive relationships, and positive relationship skills [16-18]. Additionally, empirically-supported bystander programs, which have been evaluated in high schools, attempt to address school culture by targeting students’ attitudes and beliefs about relationship and sexual violence and encouraging behaviors designed to prevent it from occurring [29-32]. Although such prevention efforts have proven fruitful, the present findings suggest that addressing trauma symptoms, and perhaps other factors occurring in the aftermath of TDV, may aid ongoing efforts to prevent future victimization. Related to this point, there already are several empirically-supported, school-based programs for addressing teens’ trauma symptoms (e.g., CBITS [33], Trauma and Grief Component Therapy for Adolescents [34]). Given the prevalence of TDV and extensive research identifying adolescence as a critical developmental period for future functioning in many domains (e.g., family, work) [35], our findings suggest that addressing trauma symptoms during the high school years may be beneficial, particularly to females, as they transition into adulthood, and perhaps throughout their lives.

This study was not designed to evaluate why trauma symptoms might relate to physical dating violence victimization, but we offer a couple of hypotheses. First, trauma symptoms might be associated with ignoring or dismissing signs of danger in a relationship. Consistent with this idea, women who have experienced repeated victimization tend to display longer latencies in recognizing situations as dangerous [36]. Second, trauma symptoms might also be associated with feeling detached from one’s social network, which can interfere with coping and help-seeking behavior to deal with and prevent future violence [10]. It should be noted, however, that while the model tested implies trauma symptoms cause physical dating violence victimization (and physical TDV causes trauma symptoms), the documented associations might still be explained by unmeasured third variables. That is, the prospective design and data analytic approach permits conclusions about the temporal sequencing of dating violence experiences and trauma symptoms; however, third variables, such as growing up in a violent family, experiencing multiple forms of abuse, and mental health problems such as depression and substance abuse, might be contributing to certain results.

In the present study, the prevalence rates for physical dating violence victimization did not differ significantly for males and females across the two assessment points. Females reported experiencing more acts of physical dating violence than males during the high school assessment, but not during the follow-up assessment in early adulthood. These findings are consistent with reviews of the literature on gender discrepancies in adolescents’ experiences of partner violence, which conclude it is unclear if males and females differ on victimization rates [37]. However, physical TDV victimization was associated with trauma symptoms for females, but not for males, a finding that is consistent with dozens of studies evaluating the consequences of IPV for adult men and women. Specifically, compared to males, females tend to experience more problematic mental health symptoms [19], hospitalizations, and medical treatment because of physical injury as a result of IPV [38]. Given the gender discrepancy in how males and females experience TDV, future research may consider whether gender-focused interventions are useful for targeting the unique experiences of female teens.

Although this study has a number of strengths, including the longitudinal follow-up of a large sample of ethnically diverse adolescents, certain limitations should be considered. First, as noted above, the model tested implies that physical TDV causes trauma symptoms, which in turn places teens at risk for experiencing additional incidents of physical TDV. The documented associations, however, might be explained by unmeasured third variables that are linked to both experiencing physical dating violence and trauma symptoms. Second, data on trauma symptoms were collected with brief, self-report screening measure. Although the measure employed may be valid for the purpose of screening for significant trauma symptomatology [23], a screening measure may not have been ideal for the present research. For example, the measure did not link the trauma symptoms reported by participants to past incidents of TDV. A more comprehensive assessment of trauma symptoms would allow for a more precise analysis of how TDV may lead to trauma symptoms, as well as the role played by trauma symptom in re-victimization. Third, data on both dating violence victimization and trauma symptoms were obtained via adolescent self-report measures. A convergence of findings across data collected via different methods (e.g., self-report and reports from others) would provide increased confidence in the findings from this research.

Despite these limitations, the present research contributes to the literature by providing a rigorous test of the hypothesis that teens’ trauma symptoms mediate the experience of repeated incidents of physical dating violence over time, and by showing support for this mediation model for females. Such findings hold potentially important implications for school-based efforts for reducing victimization experiences, both in high school and afterward. Specifically, school-based efforts to reduce victimization may be enhanced by supplementing existing efforts with empirically-supported programs for addressing trauma symptoms.

Implications and Contribution.

The present research showed that trauma symptoms mediated the longitudinal association between physical teen dating violence victimization and later dating violence victimization in early adulthood. When examining this model across genders, the mediation model held for females but not for males. Trauma symptoms should be addressed in comprehensive efforts designed to prevent future victimization experiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This research was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, K23HD059916 (PI: Temple), and from the National Institute of Justice, 2012-WG-BX-0005 (PI: Temple). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the sponsor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Halpern CT, Spriggs AL, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Patterns of intimate partner violence Victimization from adolescence to young adulthood in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(5):508–516. doi : 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vagi KJ, Olsen EO, Basile KC, Vivolo-Kantor AM. Teen dating violence (physical and sexual) among US high school students: Findings from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169:474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spriggs AL, Halpern CT, Martin SL. Continuity of adolescent and early adult partner violence victimization: Association with witnessing violent crime in adolescence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;63:741–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez AM. Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: Child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth & Society. 2011;43:171–192. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PH, White JW, Holland LJ. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1104–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foa EB, Cascardi M, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Psychological and environmental factors associated with partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2000;1:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noll JG, Grych JH. Read-react-respond: an integrative model for understanding sexual revictimization. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:202–215. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman L, Dutton MA. Role of distinct PTSD symptoms in intimate partner reabuse: A prospective study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis SF, Fremouw W. Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:105–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez S, Johnson DM. PTSD compromises battered women's future safety. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;0:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cascardi M, Jouriles EN. A Study Space Analysis and Narrative Review of Trauma-Informed Mediators of Dating Violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;0:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, et al. The safe dates project. Prev Res. 2000;7:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaycox LH, McCaffrey D, Eiseman B, et al. Impact of a school-based dating violence prevention program among Latino teens: Randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, et al. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:692–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coker AL, Weston R, Creson DL, et al. PTSD symptoms among men and women survivors of intimate partner violence: The role of risk and protective factors. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:625–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wekerle C, Wolfe DA, Hawkins DL, et al. Childhood maltreatment, posttraumatic stress symptomatology, and adolescent dating violence: Considering the value of adolescent perceptions of abuse and a trauma meditational model. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:847–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temple JR, Shorey RC, Fite P, et al. Substance use as a longitudinal predictor of the perpetration of teen dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013:42:596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, et al. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychol Assess. 2001;13:277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prins A, Ouimette P. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2004;9(4):151–151. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang-Wallentin F, Jöreskog KG, Luo H. Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with misspecified models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2010;17:392–423. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei P. Evaluating estimation methods for ordinal data in structural equation modeling. Quality and Quantity. 2009;43:495–507. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks-Russell A, Foshee VA, Ennett ST. Predictors of latent trajectory classes of physical dating violence victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:566–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sargent KS, Jouriles EN, Rosenfield D, McDonald R. A high school-based evaluation of TakeCARE, a video bystander program to prevent adolescent relationship violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;0;1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook-Craig PG, Coker AL, Clear ER, et al. Challenge and opportunity in evaluating a diffusion-based active bystanding prevention program green dot in high schools. Violence Against Women. 2014;10;1179–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz J, Heisterkamp HA, Fleming WM. The social justice roots of the mentors in violence prevention model and its application in a high school setting. Violence Against Women. 2011;6;684–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller E, Tancredi DJ, McCauley HL, et al. One-year follow-up of a coach-delivered dating violence prevention program: A cluster randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45;108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saltzman WR, Pynoos RS, Layne CM, et al. Trauma-and grief-focused intervention for adolescents exposed to community violence: Results of a school-based screening and group treatment protocol. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2001;5(4):291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52;83–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson AE, Calhoun KS, Bernat JA. Risk recognition and trauma-related symptoms among sexually revictimized women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hickman LJ, Jaycox LH, Aronoff J. Dating violence among adolescents prevalence, gender distribution, and prevention program effectiveness. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2004;5(2):123–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tjaden PG, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2000:181867. [Google Scholar]